11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

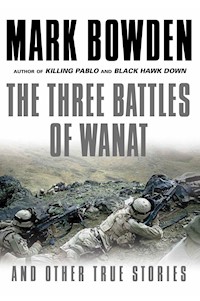

Ranging from war journalism to crime stories to profiles on influential leaders to pieces on sports, gambling and the impending impact of supercomputers on the practice of medicine, this collection is Bowden at his best. Pieces that will appear in the collection include, "The Three Battles of Wanat", which tells the story of a bloody engagement in Afghanistan and the extraordinary years-long fallout within the US military, "The Drone Warrior," in which Bowden examines the strategic, legal and moral issues surrounding armed drones, and "The Case of the Vanishing Blonde," which first appeared in Vanity Fair and recounts the chilling story of a woman who went missing from a Florida hotel only to turn up near the Everglades, brutally beaten, raped and still alive. Also included are profiles on a diverse range of notable and influential people such as Joe Biden, Kim Jong-un, Judy Clarke who is well known for defending America's worst serial killers and David Simon, the creator of the successful HBO series The Wire.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

The Three Battles of Wanat

Also by Mark Bowden

Doctor Dealer

Bringing the Heat

Black Hawk Down

Killing Pablo

Finders Keepers

Road Work

Guests of the Ayatollah

The Best Game Ever

Worm

The Finish

The Three Battles of Wanat

and Other True Stories

Mark Bowden

Grove Press UK

First published in the United States of America in 2016 by Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Inc.

Copyright ©Mark Bowden, 2016

The moral right of Mark Bowden to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

“The Three Battles of Wanat” (originally published as “Echoes from a Distant Battlefield”), “The Inheritance,” and “The Bright Sun of Juche” (originally published as “Understanding Kim Jong Un, the World’s Most Enigmatic and Unpredictable Dictator”) originally appeared inVanity Fair

“The Ploy,” “The Last Ace,” “The Killing Machines,” “Jihadists in Paradise,” “Just Joe” (originally published as “The Salesman”), “The Angriest Man in Television,” “The Measured Man,” “The Hardest Job in Football,” “The Man Who Broke Atlantic City,” “The Story Behind the Story,” “The Great Guinea Hen Massacre,” “Rebirth of the Guineas,” “Cry Wolfe,” “Abraham Lincoln is an Idiot” (originally published as“‘Idiot,’ ‘Yahoo,’ ‘Original Gorilla’: How Lincoln Was Dissed in His Day”), “Dumb Kids’ Class,” and “Zero Dark Thirtyis Not Pro-Torture” originally appeared in theAtlantic

“Attila’s Headset” originally appeared in theNew Yorker

“Saddam on Saddam” originally appeared in thePhiladelphia Inquirer

“The Silent Treatment” originally appeared inSports Illustrated

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 557 9

Ebook ISBN 978 1 61185 968 3

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press, UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

For John Hersey

Contents

Introduction

WAR

The Three Battles of Wanat

The Ploy

The Last Ace

The Killing Machines

Jihadists in Paradise

PROFILES

Just Joe

The Inheritance

The Bright Sun of Juche

Defending the Indefensible

The Angriest Man in Television

The Measured Man

SPORTS

The Silent Treatment

The Hardest Job in Football

The Man Who Broke Atlantic City

Attila’s Headset

ESSAYS

The Story Behind the Story

The Great Guinea Hen Massacre

Rebirth of the Guineas

Cry Wolfe

Abraham Lincoln Is an Idiot

Dumb Kids’ Class

Saddam on Saddam

Zero Dark Thirty Is Not Pro-Torture

Acknowledgments

Introduction

I am particularly grateful to Vanity Fair and the Atlantic for supporting not just me, but so many other journalists intent on treating ideas and stories in depth. In my early work as a newspaper reporter I often felt that my finished stories had just scratched the surface. Like many reporters, I was in a running battle with my editors for more time and more space. Fortunately, I have had very sympathetic editors. Deeper investment usually resulted in a richer story.

Take, for example, Wanat, the title story of this collection. When my editor at Vanity Fair, Cullen Murphy, first suggested it to me in August 2010, I envisioned it as a detailed account of a tragic 2008 battle in Afghanistan that had left nine American soldiers killed and twenty-seven wounded. I had not written a story about combat since Black Hawk Down ten years earlier. This new one concerned a mountain combat outpost under construction that had been attacked by a large Taliban force and nearly overrun. When I began I imagined a story much like the one I told in that book.

But true stories are never alike. The more you stir, the thicker the stew. I was surprised to discover, when I started reporting, that there had been not one but several detailed investigations of what had happened at Wanat. The one that had received the greatest attention was a preliminary draft of a study by the U.S. Army Combat Studies Institute. Written by Douglas Cubbison, a contract military historian, it was sharply critical of the army units involved, placing blame for inadequate defenses at Wanat on poor command decisions.

Cubbison’s draft had inspired detailed stories by the Washington Post, by NBC News, and by the noted military affairs blogger Tom Ricks. It was indeed rare for a study from that source to be controversial, and especially for it to be so sharply critical of officers still serving. One of the things that made Cubbison’s take on Wanat so attractive to reporters was the poignant human story behind it. The institute’s study had been instigated by Dave Brostrom, the father of Jonathan Brostrom, a young lieutenant who had been killed in the fight. Dave Brostrom, a retired army colonel, had examined detailed reports about the incident, and had become convinced that the death of his son and the others at Wanat had resulted from incompetent or reckless leadership. When I spoke with Cubbison it became clear that Dave Brostrom not only had requested the report but had played an important role in shaping it. The story of a career army officer determined to hold his peers accountable was irresistible.

But after meeting Dave Brostrom; Lieutenant Colonel Bill Ostlund, the officer who bore the brunt of his criticism; and others involved up and down the command chain, I found a story far more complex than that. It involved a grieving father troubled not only by command decisions in Afghanistan but also by his own role in placing his son at that vulnerable combat outpost. It involved commanders struggling to fulfill a difficult mission with limited men and resources at a time when the primary American military focus had shifted to Iraq. The string of reports and findings ended, ironically, by faulting, of all people, Jonathan Brostrom. Vanity Fair published my account in December 2011, nearly a year and a half after Cullen first suggested it to me. Without the time and editorial support to fully explore all of these branches of the story, and to travel and meet personally with those directly involved, I would never have been able to arrive at my own fuller understanding of what happened.

However my own use of the opportunity is judged, magazines (now also websites) that encourage long-form reporting and writing are carrying on one of the great traditions in American journalism. From the work of abolitionists who recorded the brutal practices of slave owners; Nellie Bly’s famous trip to a madhouse for the New York World; Ida Wells’s courageous documentation of lynching; the powerful exposés of Lincoln Steffens, Ida Tarbell, Upton Sinclair, and the other great contributors to McClure’s in the early twentieth century; and the work of John Hersey, Gay Talese, and Truman Capote to the flamboyant New Journalists of Rolling Stone, Ramparts, Harper’s, and Esquire who so inspired me as a college student, journalists free to explore every branch of a complex story have produced a body of work every bit as important to the canon of American literature as that of novelists, poets, playwrights, and screenwriters.

I see more of it today than ever, even as print publications dwindle. The Internet affords, if anything, a superior platform for every kind of journalism, and I have no doubt that long-form narratives will remain essential. Prose is the most subtle and precise form of communication: the language of thought itself. No other medium is capable of so deeply exploring and explaining human experience. At the same time that headlines and images flash around the world on cell phones instantaneously, time and again we learn that our initial take on a story is incomplete and often wrong. Whether it’s social media prominently fingering an innocent man in the days after the Boston Marathon bombing, or early reports of a “trench coat Mafia” from the scene of the Columbine High School shootings, until an independent reporter is turned loose to dig deeper and write longer, we don’t understand what really happened. This is true of the stories we think we know, and also of those we would never hear if journalists were not encouraged to follow their own noses. We would never, for instance, have heard the story of Henrietta Lacks, whose fatal tumor was used to create the cell line for cancer research worldwide, or of a quirky investor like Steve Eisman, who famously foresaw the clay feet of Wall Street’s collateralized debt obligations, and cashed in when the stock market crashed in 2007. In both of these cases, it was the professional curiosity and unique talents of Rebecca Skloot and Michael Lewis that uncovered stories essential to our understanding of the modern world.

And I don’t buy for a moment the notion that people don’t read these stories. My own experience directly contradicts it. I regard as entirely bogus the popular theory that young people, in particular, have a declining attention span or are unwilling to read anything longer than a sound bite. My children, my students, and my readers are better informed at a young age than I ever was, and are every bit as receptive as I am to a story that grabs them and won’t let them go. I also think that writers have a responsibility not to bore people. If the story is long, it had damn well better be fun to read.

I have in some cases restored these stories to the form I gave them prior to editing for publication. The demands of fitting them into magazines sometimes required making cuts I would rather not have made. I have also made corrections suggested by helpful readers, some kindly, others less so, but I am always happy to get things right.

WAR

The Three Battles of Wanat

Published as “Echoes from a Distant Battlefield,”Vanity Fair, December 2011

1. The Lieutenant’s Battle

One man on the rocky slope overhead was probably just a shepherd. Two men were suspicious, but might have been two shepherds. Three men were trouble. When Second Platoon spotted four, then five, the soldiers prepared to shoot.

Dark blue had just begun to streak the sky over the black peaks that towered on all sides of their position. The day was July 13, 2008. Captain Matthew Myer stood at the driver’s-side door of a Humvee parked near the center of a flat, open expanse about the length of a football field where the platoon was building a new combat outpost, known as a COP. The vehicle was parked on a ramp carved in the rocky soil by the engineering squad’s single Bobcat, with its front wheels high so that its TOW* missiles could be more easily aimed up at the sheer slopes to the west. The new outpost was hard by the tiny Afghan village of Wanat, at the bottom of a stark natural bowl; and the forty-nine American soldiers who had arrived just days earlier felt dangerously exposed.

* Tube-launched, optically tracked, wire-guided.

Myer gave the order for an immediate coordinated attack with the platoon’s two heaviest weapons—the TOW system and a 120-millimeter mortar—which sat in a small dugout a few paces west of the ramp surrounded by HESCO barriers, canvas and wire frames that are filled with dirt and stone to create temporary walls. The captain was walking back to his command post about fifty yards north when the attack started.

It was twenty minutes past four in the morning. Myer and Second Platoon, one of three platoons under his command scattered in these mountains, were at war in a place as distant from America’s consciousness as it was simply far away. Wanat was legendarily remote, high in the Hindu Kush, at the southern edge of Konar Province in Afghanistan’s rugged northeast. It shared a long border with the equally forbidding territories of north Pakistan. Here was the landscape where Rudyard Kipling in 1888 had set his cautionary tale, The Man Who Would Be King, about British soldiers with ill-fated dreams of power and conquest. Little had changed. It is one of the most mountainous regions of the world, with steep gray-brown peaks reaching as high as twenty-five thousand feet. Its jagged mountains towered over V-shaped valleys that angled sharply down to winding rivers. Wanat was at the confluence of the Waygul River and a small tributary. It was home to about fifty families, who carved out a spare existence on a series of green irrigated terraces that rose like graceful stairsteps to the foot of the stony eastern slopes. A single partly paved road wound south toward Camp Blessing, the headquarters for Task Force Rock—Second Battalion, 503rd Infantry Regiment, 173rd Airborne Brigade. This battalion HQ was just five miles away in the fish-eye lens of a high-flying drone, but on the ground it was a perilous journey of almost an hour—perilous because improvised explosives and ambushes were common. In Wanat it was easy to feel that you were hunkered down on the far edge of nowhere fighting the only people in the world who seemed to badly want the place. You needed something like a graduate degree in geopolitics and strategy to have any idea why it was worth dying for.

Yet killing and dying—mostly killing—were what Task Force Rock was doing here on the front lines of America’s forgotten war. In army parlance, Afghanistan had become an “economy of force” action, which meant, in so many words, “Make do.” The hopeful infrastructure and cultural development projects that had arrived with the first wave of Americans seven years earlier had dried to a trickle. Ever since President Bush had followed up rapid military success in Afghanistan with a massive invasion of Iraq in 2003, the nation’s attention had been riveted there. But the war against the Taliban, Al Qaeda, and like-minded local militias had never ended in these mountains. Small units of American soldiers were dug into scores of isolated tiny combat posts, perched high on promontories, crouched behind HESCO walls and barriers of concrete and sand, ostensibly projecting the largely theoretical Afghan central government into far-flung valleys and villages where politics and loyalties had been stubbornly local and tribal since long before Kipling.

Second Platoon was part of Myer’s Chosen Company, the “Chosen Few,” who wore patches on their uniforms displaying a stylized skull fashioned after the insignia of the Marvel comic book character “Punisher.” Twenty-first-century America had staked its claim to this patch of ground, punctiliously negotiating its purchase from village landlords. The platoon had occupied it in darkness, in a driving rain, just three days earlier.

Myer had arrived only the day before. He had sketched out a basic plan for the outpost, and then left supervision of the construction to First Lieutenant Jonathan Brostrom, a cocky, muscular, popular twenty-four-year-old platoon leader from Hawaii. Brostrom had a long, slender face, and dark brown hair worn, like the other soldiers’, in a buzz cut, high and tight. His body had been sculptured by daily weight lifting over the fourteen months of this deployment. After consultations with Myer and the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Bill Ostlund, the lieutenant had drawn up detailed maps of the new outpost on whatever scraps of paper he could find, so that he could show his men sectors of fire for all of the vehicles, placement of the Claymore mines, fighting positions, latrine, and everything else. A small force of Afghan engineers with heavy equipment were to handle most of the construction, but they had been delayed at Camp Blessing, awaiting the completion of a road-clearing mission that would enable them to make the trip safely. In the interim, the platoon itself had begun digging out and building the outpost’s preliminary defenses, toiling through hundred-degree-plus days with limited water and resources, hacking away at the baked, stubborn soil with picks and shovels, building sandbag walls, stringing razor wire, and filling the HESCOs as well as they could—the Bobcat could not reach high enough to dump earth into the frames, so they had been cut down to just four feet.

The men of the platoon had felt particularly vulnerable in these first days, expecting to be attacked. It was particularly unsettling because they had nearly completed their hazardous tour. They were just two weeks away from heading home. Platoon Sergeant David Dzwik had rallied them as best he could to complete this dangerous assignment before leaving, pointing out that they had signed on to fight for the whole fifteen-month tour, and how they were better equipped to handle the danger than the inexperienced troops who would replace them. But down deep Dzwik shared their misgivings. He hated both the task and the location.

It wasn’t just that the outpost sat at the bottom of a giant bowl. There were dead zones all around it where you couldn’t see. The ground dipped down just outside the perimeter, down to the creek, which ran to the west, and to the road that bordered it to the southeast. The battalion could not provide them with steady, overhead visual surveillance because of weather and limited availability of drones. So they lacked a clear eye on the terrain. Where the land sloped uphill to the northeast there were the bazaar and the mosque and other buildings. It was as though the Afghan village—and Dzwik was a long way from trusting even the Afghans whom he knew—were staring right down at them. There were just too many places for the enemy to hide. In the preceding weeks, he had heard reports of Taliban by the hundreds gathering for an attack on Bella, the outpost they had evacuated to move here. They had managed to clear out before that attack came, but Bella was only four or five miles north. And even though the terrain was formidable, the enemy was skilled at moving rapidly and silently through it. Worse, everybody in the Waygul Valley knew exactly where the Americans had purchased property and planned to resettle.

Dzwik was a puckish, solid, career soldier from Michigan who enlisted after starring on the gridiron in high school and realizing that he would never be able to sit still long enough to finish college. He was fit and full of youthful energy, and after a boyhood spent hunting, fishing, and camping he took readily to the rigors of military life. He had been in the army now for thirteen years and planned to stay until retirement, even though the job meant spending precious little time at home with the wife and three kids. This was his second tour in Afghanistan. He had inherited the position of platoon sergeant when his predecessor, the man for whom this COP was named, Sergeant First Class Matthew Kahler, had been killed by a shot fired by a “friendly” Afghan soldier. The army had ruled it an accident, but Dzwik, like many in the platoon, wasn’t convinced. They considered the tragedy of Matt Kahler’s death somehow emblematic of the whole Afghan conflict.

Despite the precarious position they now occupied, Dzwik had been forced to slow construction of defenses because of the extreme heat and limited water supplies. Gradually, as the stunted HESCOs were filled and as shallow excavations were chipped out, their position improved, and Dzwik found himself hating it a little less. When Myer arrived on the fourth day, the captain was impressed by all that had been accomplished, but he could see that the COP was still far from secure.

All of the fighting positions were makeshift. The command post was a sunken space about two feet deep, no larger than a big conference table, framed by Dzwik’s Humvee, a line of HESCOs, and the outer mud wall of a structure built to house the village’s bazaar. Southward down the gentle sloping ground were the TOW Humvee, parked on the ramp; two mortar positions similarly excavated and surrounded by HESCO walls; and, farther south toward the road, two more positions, the closer one marked by a Humvee, and beyond it an Afghan army position, placed there to man the outer checkpoint on the road. There were several more dugout fighting positions to the north, and two larger positions toward the northern edge manned by the Afghan troops, with two Humvees armed with M-19 grenade launchers. The Bobcat was already at work that morning digging a trench around one of the mortar positions to drain off water that had pooled in it the day before.

The biggest problem was obvious: the platoon did not control the high ground. Every outpost on this frontier had observation posts high in the hills to spot approaching enemy troops, and sent out regular foot patrols to make contact with the locals and to discourage hostile approaches. Lacking enough men for both construction and patrolling, Brostrom had chosen to concentrate on construction. He had sent several perfunctory patrols just to scout the immediate vicinity, but that was it. And the platoon had yet to establish a useful observation post.

It was a pressing priority. As Myer was giving the order to fire that morning, Brostrom was busy assembling a thirteen-man patrol to look for a suitable location in the hills to the south. As was the daily practice, the entire platoon had all been up for almost an hour, all the men dressed in full battle gear and “standing-to” their small fighting positions.

They did have one elevated position, which they called Topside, and it was visible to the northeast over the rooftops of the bazaar. The nine men there had two machine guns and a grenade launcher in three fighting positions behind a maze of low sandbag walls and a loose perimeter of unstaked razor wire. Topside was midway up the lazy terrace steps, and was set against three large boulders. Myer was not happy with it. It was not high enough to be very useful, and the men there were dangerously isolated from the main force. But he could understand Brostrom’s thinking. Any farther away, Topside would have been impossible to quickly reinforce. Until the promised engineering group arrived and freed up more men to patrol, it was about as far away as the platoon dared to put it. As it was, it would be hard to defend if it came under attack.

Which it did, suddenly, on this morning. Two long bursts of machine-gun fire were followed immediately by a crashing wave of rocket-propelled grenades, or RPGs. It felt and sounded as if a thousand came at them at once, deafening blasts and fiery explosions on all sides, from close range and continuing without letup. Myer judged that the first had come from behind the homes looking down on them from Wanat, but soon enough they were zeroing in from everywhere. The TOW and mortar teams had not yet fired; they had still been checking grid numbers when the onslaught began.

Myer ran the rest of the way to the command post, ducking behind cover and standing in the open door of his Humvee beside his radio operator Sergeant John Hayes, who had two FM radios, one tuned to the platoon’s internal net and the other to the battalion headquarters at Camp Blessing.

“Whatever you can give me, I’m going to need,” Myer told headquarters calmly, the sound of intense gunfire and explosions in the background lending all the emphasis his words needed. “This is a Ranch House–style attack,” he said, referring to the worst single assault his men had experienced months earlier at an outpost by that name farther north.

No one at Wanat expected this level of intensity to continue for long. Often a single big show of force—an artillery volley or a bomb dropped from an aircraft—would be enough to end things. The enemy would typically scatter. But Wanat was too remote to get help fast. The closest air assets were at the Forward Operating Base Fenty in Jalalabad, and it would be nearly an hour before planes or choppers would arrive. Reinforcements by road would take at least forty-five minutes. The big guns at Blessing had to be pointed nearly straight up to lob shells over the mountains; this diminished their effectiveness, especially when the enemy was so close to the outpost. Some Taliban were shooting from the newly dug latrine, right on the western perimeter.

Myer directed artillery to fire on the riverbed that ran near the latrine ditch along the western edge of the village. It might not hit anyone, but the blast alone might make the enemy think twice.

“Hey, shoot these three targets,” he said; “then we can adjust them as needed.”

Before he had time to finish that order, the main source of enemy fire had shifted to the northeast, toward Topside, which was getting hammered. Grenade explosions could be heard.

“We have to do something,” said Brostrom. The men were too pinned down to assemble a large group, but the lieutenant knew Topside was outgunned. “We have to get up there,” he said.

“OK, go,” said Myer.

It was like the lieutenant to insist on joining the firing line. It had been an issue between him and the captain. Myer was six years older than Brostrom, with five long years of experience in warfare in Iraq and Afghanistan. He saw in Brostrom a tendency shared by many talented young officers; they became too chummy with their men. Brostrom was always hanging around with them, lifting weights, joking; he had joined the army out of ROTC at the University of Hawaii, and, with his every-present Oakley shades and his surfer nonchalance, he wore the burdens of command lightly. He had once signed an e-mail to Myer, “Jon-Boy,” and that struck Myer—a West Point grad—as characteristically off-key. Of a piece, as Myer saw it, was Brostrom’s inclination to wade forward into a fight alongside his men. Much as that endeared him to the platoon, it was sometimes unwise. There were times Myer had needed him at the command post in a fight and couldn’t find him. The captain would be juggling urgent requests for artillery and air support, and calculating grids, while Brostrom, who might have helped him, was instead off shooting a rifle.

“That’s not what your role is,” the captain had explained later. “You need to be able to bring more than an M-4 to the fight. You have all these other assets that you bring, which is more firepower than the rest of the platoon combined.”

Brostrom had acknowledged it, and was working on it, but this situation was different. The need was dire, and both officers knew it.

The lieutenant ran to the fighting position of the platoon’s second squad. After a short consultation there, he took off with Specialist Jason Hovater and the platoon’s medic, Private William Hewitt. No sooner did they emerge from cover than Hewitt was hit by a round that blew a hole as big as a beer can out of the back of his arm. He crawled back toward cover and began bandaging himself. Brostrom and Hovater, the fastest runner in the platoon, continued up toward Topside.

It was not immediately obvious—too much was happening at once—but the enemy’s attack was cunning and well orchestrated. The Taliban were primarily targeting the platoon’s crew-served weapons. The Humvee with the TOW missile system had been hit hard right at the outset—it hadn’t gotten off a shot. Two RPGs hit the driver’s side, one setting the engine ablaze and the other exploding against the driver’s-side rear. A third RPG exploded against the rear of the passenger side. The engine was destroyed, and the vehicle caught fire. The three-man TOW team fled to take cover in the command post, leaving nine unfired missiles trapped in the inferno.

Dzwik had been walking over to the horseshoe-shaped 120-millimeter mortar pit when the shooting started. He was at the entrance when he heard the first shots, and in front of him Specialist Sergio Abad was hit by a round that clipped the back side of his body armor and entered his chest. He was still talking and breathing, but the wound was severe, and would prove mortal. As Dzwik dived for cover, he dropped his radio mike into the pool of water inside the pit. That effectively removed him from the command loop. He was just another rifleman now. Attackers were firing into the pit from the roofs of village dwellings and from a clump of trees just beyond the perimeter wire.

The platoon was used to exchanging fire with the enemy, but for many this was the first time they could actually see who they were shooting at—and who was shooting at them. Some of the enemy fighters wore masks. They were dressed in various combinations of combat fatigues and traditional Afghan flowing garments. Dzwik watched one enemy fighter, high in the trees with a grenade launcher, who had a perfect bead down on their flooded pit. But every time the shooter launched a grenade, its fins would clip leaves and branches and spin off wildly. Others were firing from the rooftops of the village dwellings, from behind the bazaar, and from the cover afforded by the terrain on all sides. This was clearly a well-planned, well-supplied, coordinated assault.

The mortar crew fought back with grenades and small arms, with the engineering squad feeding them ammo. They managed to fire off four mortars before machine-gun rounds began pinging off the tube. One RPG flew right through an opening in the HESCO wall, passing between Staff Sergeant Ryan Phillips, the crew leader, and Private Scott Stenowski, then on across the outpost to explode against the bazaar wall, setting it on fire. When an RPG exploded inside the pit, injuring two more soldiers and sending sparks from the store of mortar rounds, Phillips ordered everyone out. Carrying Abad, they ran to the now jammed command post.

Dzwik felt as if he were moving in slow motion, rounds crackling across the empty space and kicking up dust at his feet.

It was hard to believe the enemy had so many grenades to shoot. Everyone kept waiting for a lull, but it didn’t come. The village had clearly been in on the attack, stealthily stockpiling RPGs for days, if not weeks. There had been clues: unoccupied young men just sitting and watching the post under construction over the last few days, as if measuring distances, observing routines, counting men and weapons. The men of the platoon had sensed that they were being sized up, but what could they do? They couldn’t shoot people for just standing and watching. There had been a few warnings that an attack was coming, one just the night before, but they believed on the basis of long experience that they had time. Ordinarily the enemy would work up to a big attack, preceding it with a small unit assault on one position, a lobbed grenade, or a few mortars from the distance. This is what experience had taught them to expect. Not a massive attack completely out of the blue.

Inside the crowded command post, Myer worked the radio furiously, trying to guide Camp Blessing’s artillery crews. Communications were spotty, because the destruction of the TOW Humvee had taken out the platoon’s satellite antenna. He was working up grids for aircraft and artillery, trying to figure out exactly what was going on, and hoping to land a few big rounds to end this thing. He was struggling to stay calm and think methodically. He knew Lieutenant Colonel Ostlund would have already dispatched a reaction force, and would be steering in air support—bombers and Apache gunships. Myer took stock of his remaining assets, and where the enemy was concentrated. He guessed that the Taliban leaders believed they were too close to the perimeter for artillery rounds to be used effectively. If he could just drop a few shells close enough to disabuse them of this notion, maybe they would break off.

At that point the captain was relying on his men to do what they had been trained to do. He left cover briefly to check in at the two closest firing positions, moving with rounds snapping nearby and the chilling sight of RPGs homing in—he could actually see them approaching, arcing in eerily from the distance. He was back inside the command post when the burning TOW Humvee exploded, throwing missiles in all directions. Two landed inside the command post, one with its motor still running. Phillips grabbed one, using empty sandbags to protect his hands from the hot shell, and carried it out of the crowded command post under heavy fire, depositing it a safe distance away and then returning miraculously unharmed. Myer grabbed the other one and hurled it up and over the sandbag wall. A flap of fabric from the HESCO wall began to smolder, filling the crowded space with black smoke.

At the same time, six minutes into the fight, the howitzer shells began to fall, beginning with four big blasts on the southern and western sides of the outpost. Ostlund had delayed firing until he was able to confirm, with Myer, the location of every member of the platoon. He had the crews perform a mandatory recheck before each 155-millimeter shell was fired. Out of concern, again, for their own comrades, the howitzer battery had armed the shells with delay fuses, which gave those on the ground a chance to dive for cover, an advantage that also helped the enemy. Nevertheless, the barrage became a steady, slow, loud drumbeat. It did little to check the assault.

All of the fighting positions at the post were heavily and continually engaged at this point. The Afghan contingent, with their three U.S. Marine trainers, were firing from their bunkers to the eleven o’clock and five o’clock positions with small arms and M-240 machine guns. The two Humvees with M-19 grenade launchers were unable to use them because the enemy was within the weapon’s minimum arming distance. The last of the platoon’s Humvees, at the lower position, had its fifty-cal taken out early on. Specialist Adam Hamby had been pouring rounds at a spot where he had seen an RPG launched. Amazingly, fire increased from that spot. As he ducked down to reload, the inside of his turret exploded from the impact of bullets, one of which hit the weapon’s feed tray cover, which he had raised to reload. The hit had disabled the weapon.

So, minutes into the fight, the platoon was left to defend the main outpost with small arms, shoulder-fired rockets, hand-thrown grenades, the fifty-cal machine gun mounted on Myer’s Humvee at the command post, and the M-240s. The weapons systems that Ostlund had freed up to give the platoon some additional firepower, the mortars and TOW system, were destroyed. Much of the incoming fire now was concentrated on the command post and its big machine gun. The Humvee was taking a pounding. Moving from point to point on the outpost was dangerous, but there were now occasional lulls, which enabled Myer and Dzwik to maneuver men along the perimeter as the fight shifted. Mostly the besieged platoon remained hunkered into its fighting positions, returning fire ferociously, and waiting for help or for the enemy to back off.

“Where is my PO [platoon officer]?” shouted Dzwik. “Where’s Lieutenant Brostrom?”

The veteran platoon sergeant and the laid-back lieutenant from Hawaii had been inseparable for months. Theirs was a familiar army relationship, the older, experienced sergeant charged with mentoring a younger, college-educated newbie who outranked him, and it was rarely frictionless. But Dzwik and Brostrom had clicked. They got along like brothers, with the platoon sergeant feeling both a personal and a professional responsibility for his lieutenant. Sometimes he felt he was keeping Brostrom on a leash. When Myer had chewed out the lieutenant for leaving the radio in a firefight to shoot his weapon, Dzwik had been chewed out at the same time by the company’s first sergeant.

“Why the hell are you letting the PO get away from the radio?” the first sergeant asked. “You need to stop him from doing stupid stuff like that.”

But Brostrom was fun, and brought out Dzwik’s playful streak, whether it was by means of video games or lifting weights or watching movies. Dzwik had taken him on as a friend and as a project. He was alarmed now to find him absent from the command post, and relieved to hear that he was absent this time with the captain’s permission.

“He went up to the OP,” said Myer.

Bad as things were on the main outpost, they were much worse at the observation post. After the battle, the battalion intel officer would surmise that the assault had been designed to wipe out the smaller force at Topside. The heavy fire would pin down the bulk of the platoon and disable its big weapons while the smaller position was overrun. Brostrom had intuited this weakness quickly, and had raced to help his men.

They were in big trouble. All nine men had been either killed or wounded. Specialist Tyler Stafford was blown backward by the blast, losing his helmet. Bits of hot shrapnel cut into his legs and belly, and at first, because of the burning sensation, he thought he was on fire. He rolled and screamed before he realized that there was no fire, just pain. He pulled his helmet on again and called for help to his buddy, Specialist Gunnar Zwilling, who looked stunned. Then Zwilling disappeared in a second blast that blew Stafford down to the bottom terrace.

Specialist Matthew Phillips, the platoon’s marksman, was on his knees below a wall of sandbags nearby.

“Hey, Phillips, man, I’m hit!” shouted Stafford. “I’m hit! I need help!”

Phillips smiled over at him, as if to say he would be there in a moment. He then stood to throw a grenade just as another RPG exploded. Stafford ducked and felt something smack hard against the top of his helmet, denting it. When the dust settled he looked up. Phillips was still on his knees, only slumped over forward, arms akimbo.

“Phillips! Phillips!” shouted Stafford, but his buddy did not stir. He was dead.

Stafford crawled back up to Topside’s southernmost fighting position, where he found Staff Sergeant Ryan Pitts, the platoon’s forward observer, severely wounded in the arms and legs. Alongside, Specialist Jason Bogar and Corporal Jonathan Ayers were putting up a heroic fight. Bogar had his Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW) on cyclic, just loading and spraying, loading and spraying, until it jammed. The barrel was white-hot. Ayers was working an M240 machine gun from the terrace overhead until he ran out of ammo. He and Specialist Chris McKaig were also struggling to put out a fire inside their small fighting position. When Ayers’s machine-gun ammo was gone, they fought back with their M-4s, popping up at intervals to shoot short bursts until Ayers was shot and killed. McKaig’s weapon overheated, so he picked up Ayers’s, only to find that it had been disabled by the shot that killed him.

The remaining men at Topside fought back with small arms, throwing grenades, and detonating the Claymore mines they had laid around the perimeter. Bogar tied a tourniquet around Pitts’s bleeding leg.

Meanwhile, under heavy fire, Brostrom and Hovater raced uphill along one wall at the lower portion of the bazaar, and then to the outer wall of a small hotel before scrambling up the first terrace. The lieutenant stood there, partly shielded by a big rock, and called up to the wounded Pitts, telling him to hand down the machine gun that Ayers had been using.

Stafford could not see Brostom and Hovater, but he heard the lieutenant shouting back and forth with a third soldier who had joined them there, Specialist Pruitt Rainey. Then he heard one of them shout, “They’re inside the wire!”

There was a crescendo of gunfire and shouting. It was surmised later that Brostrom and Rainey had been trying to set up the machine gun, with Hovater providing covering fire, when they were surprised by Taliban fighters who emerged from behind the big rock, inside the perimeter. All three were shot from the front, and killed.

The lieutenant’s battle was over. He died fully engaged. His bravery had little impact on the course of the fight. He could not rescue most of the men on Topside, and those who survived may have done so without the terrible sacrifice he and Hovater made. As it is with all soldiers who die heroically in battle, his final act would define him emphatically, completely, and forever. In those loud and terrifying minutes he had chosen to leave a place of relative safety, braving intense fire, and had run and scrambled uphill toward the most perilous point of the fight. A man does such a thing out of loyalty so consuming that it entirely crowds out consideration of self. In essence, Jon Brostrom had cast off his own life the instant he started running uphill, and only fate would determine if he would be given it back when the shooting stopped. He died in the full heat of that effort, living fully his best idea of himself.

The remaining wounded soldiers at Topside fought on. Eventually all but one, Staff Sergeant Pitts, managed to tumble and crawl their way back downhill to the platoon’s easternmost fighting position. Although wounded so severely in the legs and arms that he could not shoot his machine gun, Pitts managed to hurl grenade after grenade into the dead space alongside the perimeter, and stayed in radio contact with the command post (he would receive the Medal of Honor) until reinforcements finally came.

There was still an eternity of minutes for the living members of the platoon, fighting off a determined enemy until air support arrived, but the worst for them was over when a B-1 dropped heavy bombs to the north, and then, not long afterward, Apache gunships began raining fire on the attackers. At roughly the same time the quick reaction force arrived from Camp Blessing, having blazed up the dangerous and still uncleared road north in record time. The fight would rage on for hours, but the attackers bore the brunt of it now, as the reinforced outpost and choppers flushed them out and chased them down, exacting a heavy toll. Later inquiries would estimate that at least a third of the attacking force of two hundred to three hundred had been either killed or wounded. With the sun still behind the peaks above them to the east, Sergeant Dzwik organized nine men to follow him up to Topside.

They were still under fire as they retraced the path taken by Brostrom and Hovater. As Dzwik crested the terrace he saw bodies. For a few minutes, the shooting stopped. The scene was eerily calm. As the others fanned out to reman the observation post defenses and tend to the wounded, Dzwik took grim inventory. Eight of the day’s toll of nine killed lay here. Seven were dead. Another was mortally wounded; the sergeant’s men were busy working on him. There was a dead Taliban fighter hanging from the razor wire, and there were other bodies farther out.

Brostrom and Hovater were by the boulder. Dzwik noted that Brostrom’s mouth was open. It was a habit, one the platoon sergeant had nagged him about, telling him it made him look juvenile, or stupid. Brostrom had a comical way of carrying himself, sometimes deliberately presenting himself as the strong but dim ranger. He made people laugh. He and Dwzik were often together during briefings or meetings, and they got into trouble because the lieutenant would make him laugh and then the two of them would be giggling like high school kids in the back of the classroom. Dzwik enjoyed his role as mentor and scold. Whenever he would catch Brostrom openmouthed he was on him.

“Why is your mouth open?” he would ask. “You look retarded.”

“Shut up, man, that’s just how I am,” the lieutenant would say.

“Well, sir, I’m here to help you with that.”

Dzwik now reached down and closed the lieutenant’s mouth for him.

“I got your back, sir,” he told him.

And when the enemy fire kicked up again, Dzwik made a point of holding his ground over his fallen friend, even when an RPG exploded in the tree right above him. A piece of shrapnel tore a hole through his arm. He looked down at it, telling himself, It’s not too bad; but when a stream of blood shot out of it, he screamed.

Later, when he had been patched up, he said to his wounded comrades, “Man, I screamed like a bitch, didn’t I?”

The sun was just sliding over the surrounding peaks as word of what had happened in this isolated valley raced around the world. Nine Americans killed, thirty-one wounded (twenty-seven Americans and four allied Afghans). The Battle of Wanat was at that point the army’s worst single day in the seven-year Afghan conflict, and it would cause waves of anger and recrimination that would last for years. For nine American families in particular, the pain would last a lifetime.

The sad tidings were reported on the radio by one of the returning Apache pilots.

“I have a total of nine KIA,” he said, then added, “Godamn it!”

2. The Father’s Battle

It was a Sunday morning in Aiea, Hawaii, so Mary Jo and Dave Brostrom went to Mass. Their home is perched high on a green hillside, and in the back the ground plunges into a verdant valley of palm branches and you can gaze down on the flight of brightly colored birds. When a sudden storm sweeps through like a blue-gray shade, it will often leave behind rainbows that arch over the distant teal inlet of Pearl Harbor.

White monuments far below mark this as a military neighborhood, past and present. Camp HM Smith, headquarters for the U.S. Pacific Command, is just down the hill. The Brostroms are a military family. Dave is a retired colonel, an army aviator, who served nearly thirty years with helicopter units. Their two sons, Jonathan and Blake, had gone the same way. Jonathan was a first lieutenant and Blake was in college with the ROTC program. So when Mary Jo, a petite woman with dark brown hair and hazel eyes, saw a military van parked on Aiealani Place, their narrow residential street, she thought that somebody was misusing a government vehicle—the vans were not authorized for private use, and, on Sunday, would ordinarily have been parked on the base. They drove past it, turned down their steep driveway, and entered the house.

Dave answered the knock on the front door minutes later. There were two soldiers in full uniform.

“What’s up?” she heard him ask.

Then, “Mary Jo, you need to come here.”

She knew immediately why they had come, and she collapsed on the spot.

Dave Brostrom is a very tall, sandy-haired man with a long, lean face, a slightly crooked smile, and small deep-set blue eyes under a shock of blond eyebrows. When he talks about Jonathan, sadness seems etched in the lines around those small eyes. He moves with an athletic slouch, and his fair skin is weathered from years of island sun. In his flip-flops, flowery silk shirt, sunglasses, and worn blue jeans he doesn’t look like a military man, but the army has defined his life. He works today for Boeing, helping to sell helicopters to the units he once served.

Jonathan used to tease him about having been an aviator. There was a spirited competition between father and son, whether on surfboards—Dave had taught his sons on a tandem board—or the golf course. Jonathan was competitive by nature. He was a good golfer and an early stickler for the course rules. If Mary Jo moved a ball a few inches from behind a tree, he would announce, “One,” noting the penalty point. She didn’t like to play with him. He had golfed once, as a teenager, with his father and a general, and complained when the general tried to improve his lie.

“Sir, you can’t do that,” Jonathan said. “It’s a stroke.”

“Just go along,” counseled the veteran colonel.

“No,” Jonathan insisted. “Either he plays right or he doesn’t play at all!”

When Jonathan decided in his junior year of high school to join the army, the goal was not just to imitate his father, but to surpass him. He was determined to prove himself more of a soldier, to accumulate more badges, more decorations. He would qualify as a paratrooper, something his father had not done, and then complete air assault training. Then came Ranger school and dive school—two more elite achievements. Apart from its overt hierarchy of rank, the army has an elaborate hierarchy of status, the pinnacle of which is “special operator,” the super soldiers of its covert counterterror units. The surest path there was through an elite infantry unit. That was where Jonathan aimed. He viewed his father’s career in aviation dismissively, as a less manly pursuit than foot-soldiering. He volunteered to enlist for two extra years in order to guarantee that path. Ordinarily, ROTC officers in training will opt for the extended commitment in order to avoid the infantry, where the work is dirty and hard and the hazards are immediate, in order to steer themselves into a cushier specialty . . . like, say, aviation.

“You volunteered to spend two extra years in the army to go into infantry?” his incredulous father had asked. “That’s stupid!”

“No, it’s not,” said Jon. “I don’t want to be a wimp like you. Damn aviator.”

Dave enjoyed this kind of banter with Jonathan, but in this case the stakes were higher. He cautioned his son. It was one thing to want to show up your old man and prove you were not a wimp, but frontline infantry in wartime was not a step to be taken lightly.

“You have to understand you are going to be at the point of the spear,” said Dave. “There’s a war on.”

But Jonathan was driven. The danger was the point. His parents worried about it, but they would support their son’s ambition. Dave did more than that. He helped land his son an immediate berth with the elite airborne unit. He called his old friend Colonel Charles “Chip” Preysler, commander of the 173rd Airborne Brigade, one of the regular army’s frontline fighting units, and collected a favor. This was in 2007, just as Jonathan was completing Ranger school . . . on his third try. He had been assigned to the First Cavalry Division out of Fort Hood, a heavy armored unit that was slated for another tour in Iraq. Dave saw that the 173rd had recently been assigned a second tour in Afghanistan. So the maneuver actually satisfied both of the father’s objectives: he had helped move his son closer to his goal and also swing him away from Iraq, then the more treacherous of the army’s two theaters of war. After a two-week stint at the 173rd’s home base in Vicenza, Italy, Jonathan joined the deployed brigade in Afghanistan. His first assignment was as an assistant at Camp Blessing on the staff of Lieutenant Colonel Ostlund’s Second Battalion, Task Force Rock. Within months he was a platoon leader, commanding the outpost at Bella, and exchanging fire with the enemy. He called home excitedly after he was awarded a combat infantry badge, the army’s official recognition that a soldier has been personally engaged in ground combat.

“Is Dad home?” he asked his mother.

“No, he’s not here right now,” she said.

“Well, I need to talk to him. When will he be home? I got my combat infantry badge.”

Just then Dave walked in the door. Mary Jo handed him the phone.

“Jonathan needs to talk to you,” she said.

“I got mine!” he told his father. “I got mine!” Rubbing it in. In all his decades of service, Dave had never been in combat. Jonathan would from then on take every opportunity to remind his father of it, and Dave was happy and proud of him for it.

But the father felt another emotion. He worried about what his son had gotten himself into . . . what he had helped get his son into. There are subtleties to the ideal of courage that occur more readily to older men than young ones, more readily especially to fathers than sons. The two great errors of youth were to trust too little, and to trust too much. A man did what he had to do if necessary. To do less was cowardice. But to rush headlong toward danger? Wisdom whispered: Better than passing the test is not being put to the test. A wise man avoids the occasion of danger, as capable as he might be of meeting it. He does not risk all for too little. To the extent that he trusted in his mission and his leadership, what Jonathan was doing in seeking combat was not foolish. Danger was part of the job. The U.S. Army was in the business of managing risk and was good at it. In the modern age, it brought the men, equipment, tactics, and training to a fight with such authority that it all but guaranteed mission success, and mission success, especially in America in the modern age, meant, at least in part . . . no casualties. Well, zero casualties would be unrealistic. Death and injury were part of the job—that’s what made Jonathan’s combat infantry badge a coveted decoration. But minimal casualties. In modern war, compared with previous eras, earlier wars, death and severe injury had become blessedly rare. At the very least a soldier trusted that his commanders would not treat his existence lightly. Dave Brostrom, as much as he believed in the army, as much as he loved his country, was not so ready as his son to believe that whatever prize was to be had in a godforsaken combat outpost in the Hindu Kush was worth one’s very life. A combat ribbon lent critical authenticity to any infantry officer’s career, but what career would there be if a Taliban bullet found his boy?

A bullet had found Jonathan’s platoon sergeant and friend Matt Kahler in January, not long after he took over Second Platoon. The death of a platoon sergeant is not just a personal tragedy; it’s an organizational blow. It had shaken everyone in the brigade, up and down the ranks. The Brostroms got a phone call first from the wife of Colonel Preysler in Germany. She told them that Jonathan would be calling home, and when he had called, hours later, it was clear to Mary Jo that he had been crying. He said he had to prepare a eulogy, and she wondered, How does a twenty-four-year-old prepare a eulogy?

When Dave spoke to his friend Preysler, he asked if Preysler had been to the outpost to talk with Jonathan and the other men. Preysler said he had been unable to get there. Dave knew enough about informal army protocol to know that when someone as senior as a platoon sergeant went down, the commanders came calling to reassure the troops. Preysler hadn’t gone to the outpost, not because he didn’t care, but because his brigade was stretched too thin. He was being pulled in too many directions at once.

It cast an ominous shadow. Jonathan would call them by satellite phone every two or three weeks. The conversations were short, usually coming early in the morning. He would assure them he was all right, and then tell them he had to go. It was clear he and his men were under a lot of pressure, and were taking regular casualties. Dave and Mary Jo found it hard to picture where exactly Jonathan was, and what he was doing.

The picture came into clearer focus, along with his parents’ misgivings, after Jon surprised them by showing up at home for a Mother’s Day party. He appeared at the door that day in May with a bouquet of flowers for Mary Jo, and was bubbling with enthusiasm for his command at Bella. He steered his parents straight to his laptop and called up pictures of his guys, and some video clips from Vanity Fair’s website, which had featured a series months earlier by writer Sebastian Junger and the late photographer Tim Hetherington, “Into the Valley of Death,” about soldiers in a sister company manning outposts in the same region. Jonathan was excited. “Here’s where I work,” he said. It was all new and very cool to him. Dave looked at the videos and had a completely different reaction. He thought, This is some bad shit.

He saw young soldiers squatting in makeshift forts in distant mountains, risking their lives for reasons he could not fathom. The military side of him came out. He knew all about COIN, the army’s counterinsurgency doctrine, which had been employed to such marked effect in the previous year by General David Petraeus in Iraq. It centered on protecting and winning over a population, turning people against the violent extremists in their midst, and it called for soldiers to leave the comfort and safety of large bases to mingle with the people where they lived. It was the only rationale Dave Brostrom could see for the risks Jonathan and his platoon were taking.

“How often do you relate to the population?” he asked. “What kind of humanitarian assistance do you give them?”

“Nope, we don’t do that anymore,” said Jonathan. “We just try to kill them before they kill us. When we go outside, it’s serious business. We’re on a kill mission patrol.”

It scared Dave. There was one picture Jonathan showed them, proudly, which drove it home. It showed him attending a shura, a conference of elders, with local villagers. The Afghan men around him were old and wizened, with long gray beards and leathery skin. They were survivors, men who had carved out a life for half a century or more in those austere mountains. Through famine, pestilence, and war. And here, apparently presiding, was his Jonathan, twenty-four years old, fresh out of army ROTC at the University of Hawaii, the little boy he had taught to surf not too long ago, with his high-and-tight haircut, a wad of tobacco stuffed in his cheek, wearing his cool sunglasses, trying to look tough. He knew that Jonathan’s transition to Afghanistan, partly because of his own intervention, had meant he had missed any kind of specialized training for the Afghan mission. He was there just weeks out of Ranger school! He didn’t speak the language. He knew nothing of Afghan history or culture. He knew bubkes about the loyalties or motivations of those tough old men around him, members of tribes isolated in those Hindu Kush valleys for centuries. Dave could readily imagine how they saw his boy. To Dave the picture showed Jonathan out of his element, and not realizing it.

“You have got to get the hell out of there,” said Dave. “You know, this is stupid. You are spread too thin. Why are you doing this? These guys are just taking potshots at you every day.”

Jonathan explained that they would soon move from Bella. Task Force Rock had inherited the outposts when it arrived in country, and Ostlund had recognized that some of the distant ones made little sense. They would be moving closer to Camp Blessing, to a new outpost that could be supplied and reinforced by ground as well as air. So it at least sounded to Dave as though the men in charge shared his concerns. But Jonathan also told him that the enemy at Bella would surely follow them south to the new place, called Wanat.

“They’re going to come after me,” he said. “They’ve threatened me.”

Jonathan was in Hawaii for two great weeks in May. Dave spent a lot of time with his son. They surfed. The Sunday before Jonathan left, the priest at their church blessed him before the congregation.

Six weeks later he was back in the same church in a coffin. Some of the grieving father’s worries about the mission came out in an interview with a local reporter, but he had nothing but praise for his son’s commanders. He told a local reporter: “His leadership at the brigade and below were probably the best you will ever find, the best in the world. But they were put in a situation where they were underresourced.”