Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

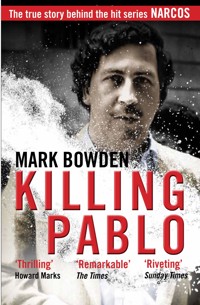

The bestselling blockbusting story of how American Special Forces hunted down and assassinated the head of the world's biggest cocaine cartel. Killing Pablo charts the rise and spectacular fall of the Columbian drug lord, Pablo Escobar, the richest and most powerful criminal in history. The book exposes the massive illegal operation by covert US Special Forces and intelligence services to hunt down and assassinate Escobar. Killing Pablo combines the heart-stopping energy of a Tom Clancy techno-thriller and the stunning detail of award-winning investigative journalism. It is the most dramatic and detailed and account ever published of America's dirtiest clandestine war.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 590

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

KILLING PABLO

Mark Bowden is the author of seven books, including Killing Pablo, Black Hawk Down and Guests of the Ayatollah. He was a reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer for twenty years and now writes for Vanity Fair, The Atlantic and other magazines. He lives in Pennsylvania, USA.

‘Powerfully written and well researched. . . Escobar was a drug emperor of such unquenchable savagery that sometimes it all palls, the statistics and paragraphs of brutality that come and go like the stuff of snorted dreams: 30 judges killed, 457 policemen, 20 murders a day for two months.’ Independent on Sunday

‘Pablo Escobar was a bona fide James Bond villain. Mark Bowden’s thrilling, completely engrossing book brings the man and his bloody times to vivid life. I couldn’t put it down.’ Howard Marks

‘A brilliant reconstruction of a manhunt. . . Clear and gripping.’ Evening Standard

‘Vivid, fast-paced and well researched.’ Sunday Times

‘A master of narrative journalism. . . Gripping reading.’ New York Times

‘Impressive.’ Washington Post

‘Compelling.’ LA Times

‘Killing Pablo reads like a Clancy-esque thriller; it’s fast-paced, full of page-turning intrigue, corruption and thwarted pursuit.’ San Francisco Chronicle

‘The season’s best thriller.’ Entertainment Weekly

‘This is investigative journalism at its best.’ Philadelphia Inquirer

Also by Mark Bowden

Black Hawk Down

Finders Keepers

Road Work

Guests of the Ayatollah

Worm

First published in the United States in 2001 by Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2001 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc.

First published in paperback in Great Britain in 2002 by Atlantic Books.

This rejacketed paperback edition published in Great Britain by Atlantic Books in 2012.

Copyright © Mark Bowden 2001

The moral right of Mark Bowden to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Picture credits: Pablo as he appeared in 1983 (Reuters NewMedia Inc./CORBIS). Map of Colombia (The Philadelphia Inquirer); Map of Medellín (The Philadelphia Inquirer). Pablo and his wife Maria Victoria in 1983 (Reuters NewMedia Inc./CORBIS); Pablo embraces his wife, Maria Victoria, and his daughter, Manuela (RCN). President Bush with Colombian president Virgilio Barco (AP/World Wide Photos); Morris D. Busby (The Philadelphia Inquirer); Luis Galán (AP/World Wide Photos); Colombian president César Gaviria (The Philadelphia Inquirer). A dinner party in the mid-1980s (Mark Bowden); Fernando Galeano (AP/World Wide Photos); A view from the comfortable living room of Pablo’s suite at La Catedral prison (Mark Bowden); DEA agents Steve Murphy and Javier Peña (Mark Bowden). Agent Joe Toft (Tim Dunn, freelance photographer); José Rodriguez-Gacha (El Espectador); Colonel Hugo Martinez (The Philadelphia Inquirer); Eduardo Mendoza (AP/World Wide Photos). An exhibit at the Policía Nacional de Colombia’s Museum (The Philadelphia Inquirer); The third page of a handwritten letter (Mark Bowden); The Colombian government and U.S. Embassy printed thousands of posters and handbills (RCN); A victim of Los Pepes (RCN). Members of Colonel Martinez’s Search Bloc (Mark Bowden); Pablo’s grave in Medellín (The Philadelphia Inquirer).

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 84354 651 1 e-Book ISBN: 978 1 84887 167 7

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

For Rosey and Zook

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

THE RISE OF EL DOCTOR

THE FIRST WAR

IMPRISONMENT AND ESCAPE

LOS PEPES

THE KILL

AFTERMATH

Sources

Acknowledgments

Index

PROLOGUE

December 2, 1993

On the day that Pablo Escobar was killed, his mother, Hermilda, came to the place on foot. She had been ill earlier that day and was visiting a medical clinic when she heard the news. She fainted.

When she revived she came straight to Los Olivos, the neighborhood in south-central Medellín where the reporters on television and radio were saying it had happened. Crowds blocked the streets, so she had to stop the car and walk. Hermilda was stooped and walked stiffly, taking short steps, a tough old woman with gray hair and a bony, concave face and wide glasses that sat slightly askew on her long, straight nose, the same nose as her son’s. She wore a dress with a pale floral print, and even taking short steps she walked too fast for her daughter, who was fat. The younger woman struggled to keep pace.

Los Olivos consisted of blocks of irregular two- and three-story row houses with tiny yards and gardens in front, many with squat palm trees that barely reached the roofline. The crowds were held back by police at barricades. Some residents had climbed out on roofs for a better look. There were those who said it was definitely Don Pablo who had been killed and others who said no, the police had shot a man but it was not him, that he had escaped again. Many preferred to believe he had gotten away. Medellín was Pablo’s home. It was here he had made his billions and where his money had built big office buildings and apartment complexes, discos and restaurants, and it was here he had created housing for the poor, for people who had squatted in shacks of cardboard and plastic and tin and picked at refuse in the city’s garbage heaps with kerchiefs tied across their faces against the stench, looking for anything that could be cleaned up and sold. It was here he had built soccer fields with lights so workers could play at night, and where he had come out to ribbon cuttings and sometimes played in the games himself, already a legend, a chubby man with a mustache and a wide second chin who, everyone agreed, was still pretty fast on his feet. It was here that many believed the police would never catch him, could not catch him, even with their death squads and all their gringo dollars and spy planes and who knew what all else. It was here Pablo had hidden for sixteen months while they searched. He had moved from hideout to hideout among people who, if they recognized him, would never give him up, because it was a place where there were pictures of him in gilded frames on the walls, where prayers were said for him to have a long life and many children, and where (he also knew) those who did not pray for him feared him.

The old lady moved forward purposefully until she and her daughter were stopped by stern men in green uniforms.

“We are family. This is the mother of Pablo Escobar,” the daughter explained.

The officers were unmoved.

“Don’t you all have mothers?” Hermilda asked.

When word was passed up the ranks that Pablo Escobar’s mother and sister had come, they were allowed to pass. With an escort they moved through the flanks of parked cars to where the lights of the ambulances and police vehicles flashed. Television cameras caught them as they approached, and a murmur went through the crowd.

Hermilda crossed the street to a small plot of grass where the body of a young man was sprawled. The man had a hole in the center of his forehead, and his eyes, grown dull and milky, stared blankly at the sky.

“You fools!” Hermilda shouted, and she began to laugh loudly at the police. “You fools! This is not my son! This is not Pablo Escobar! You have killed the wrong man!”

But the soldiers directed the two women to stand aside, and from the roof over the garage they lowered a body strapped to a stretcher, a fat man in bare feet with blue jeans rolled up at the cuff and a blue pullover shirt, whose round, bearded face was swollen and bloody. He had a full black beard and a bizarre square little mustache with the ends shaved off, like Hitler’s.

It was hard to tell at first that it was him. Hermilda gasped and stood over the body silently. Mixed with the pain and anger she felt a sense of relief, and also of dread. She felt relief because now at least the nightmare was over for her son. Dread because she believed his death would unleash still more violence. She wished nothing more now than for it to be finished, especially for her family. Let all the pain and bloodshed die with Pablo.

As she left the place, she pulled her mouth tight to betray no emotion and stopped only long enough to tell a reporter with a microphone, “At least now he is at rest.”

THE RISE OF EL DOCTOR

1948–1989

1

There was no more exciting place in South America to be in April 1948 than Bogotá, Colombia. Change was in the air, a static charge awaiting direction. No one knew exactly what it would be, only that it was at hand. It was a moment in the life of a nation, perhaps even a continent, when all of history seemed a prelude.

Bogotá was then a city of more than a million that spilled down the side of green mountains into a wide savanna. It was bordered by steep peaks to the north and east, and opened up flat and empty to the south and west. Arriving by air, one would see nothing below for hours but mountains, row upon row of emerald peaks, the highest of them capped white. Light hit the flanks of the undulating ranges at different angles, creating shifting shades of chartreuse, sage, and ivy, all of them cut with red-brown tributaries that gradually merged and widened as they coursed downhill to river valleys so deep in shadow they were almost blue. Then abruptly from these virgin ranges emerged a fully modern metropolis, a great blight of concrete covering most of a wide plain. Most of Bogotá was just two or three stories high, with a preponderance of red brick. From the center north, it had wide landscaped avenues, with museums, classic cathedrals, and graceful old mansions to rival the most elegant urban neighborhoods in the world, but to the south and west were the beginnings of shantytowns where refugees from the ongoing violence in the jungles and mountains sought refuge, employment, and hope and instead found only deadening poverty.

In the north part of the city, far from this squalor, a great meeting was about to convene, the Ninth Inter-American Conference. Foreign ministers from all countries of the hemisphere were there to sign the charter for the Organization of American States, a new coalition sponsored by the United States that was designed to give more voice and prominence to the nations of Central and South America. The city had been spruced up for the event, with street cleanings and trash removal, fresh coats of paint on public buildings, new signage on roadways, and, along the avenues, colorful flags and plantings. Even the shoe-shine men on the street corners wore new uniforms. The officials who attended meetings and parties in this surprisingly urbane capital hoped that the new organization would bring order and respectability to the struggling republics of the region. But the event had also attracted critics, leftist agitators, among them a young Cuban student leader named Fidel Castro. To them the fledgling OAS was a sop, a sellout, an alliance with the gringo imperialists of the north. To idealists who had gathered from all over the region, the postwar world was still up for grabs, a contest between capitalism and communism, or at least socialism, and young rebels like the twenty-one-year-old Castro anticipated a decade of revolution. They would topple the region’s calcified feudal aristocracies and establish peace, social justice, and an authentic Pan-American political bloc. They were hip, angry, and smart, and they believed with the certainty of youth that they owned the future. They came to Bogotá to denounce the new organization and had planned a hemispheric conference of their own to coordinate citywide protests. They looked for guidance from one man in particular, an enormously popular forty-nine-year-old Colombian politician named Jorge Eliécer Gaitán.

“I am not a man, I am a people!” was Gaitán’s slogan, which he would pronounce dramatically at the end of speeches to bring his ecstatic admirers to their feet. He was of mixed blood, a man with the education and manner of the country’s white elite but the squat frame, dark skin, broad face, and coarse black hair of Colombia’s lower Indian castes. Gaitán’s appearance marked him as an outsider, a man of the masses. He could never fully belong to the small, select group of the wealthy and fair-skinned who owned most of the nation’s land and natural resources, and who for generations had dominated its government. These families ran the mines, owned the oil, and grew the fruits, coffee, and vegetables that made up the bulk of Colombia’s export economy. With the help of technology and capital offered by powerful U.S. corporate investors, they had grown rich selling the nation’s great natural bounty to America and Europe, and they had used those riches to import to Bogotá a sophistication that rivaled the great capitals of the world. Gaitán’s skin color marked him as apart from them just as it connected him with the excluded, the others, the masses of Colombian people who were considered inferior, who were locked out of the riches of this export economy and its privileged islands of urban prosperity. But that connection had given Gaitán power. No matter how educated and powerful he became, he was irrevocably tied to those others, whose only option was work in the mines or the fields at subsistence wages, who had no chance for education and opportunity for a better life. They constituted a vast electoral majority.

Times were bad. In the cities it meant inflation and high unemployment, while in the mountain and jungle villages that made up most of Colombia it meant no work, hunger, and starvation. Protests by angry campesinos, encouraged and led by Marxist agitators, had grown increasingly violent. The country’s Conservative Party leadership and its sponsors, wealthy landowners and miners, had responded with draconian methods. There were massacres and summary executions. Many foresaw this cycle of protest and repression leading to another bloody civil war—the Marxists saw it as the inevitable revolt. But most Colombians were neither Marxists nor oligarchs; they just wanted peace. They wanted change, not war. To them, this was Gaitán’s promise. It had made him wildly popular.

In a speech two months earlier before a crowd of one hundred thousand at the Plaza de Bolívar in Bogotá, Gaitán had pleaded with the government to restore order, and had urged the great crowd before him to express their outrage and self-control by responding to his oration not with cheers and applause but with silence. He had addressed his remarks directly to President Mariano Ospina.

“We ask that the persecution by the authorities stop,” he’d said. “Thus asks this immense multitude. We ask a small but great thing: that our political struggles be governed by the constitution. . . . Señor President, stop the violence. We want human life to be defended, that is the least a people can ask. . . . Our flag is in mourning, this silent multitude, this mute cry from our hearts, asks only that you treat us . . . as you would have us treat you.”

Against a backdrop of such explosive forces, the silence of this throng had echoed much more loudly than cheers. Many in the crowd had simply waved white handkerchiefs. At great rallies like these, Gaitán seemed poised to lead Colombia to a lawful, just, peaceful future. He tapped the deepest yearnings of his countrymen.

A skillful lawyer and a socialist, he was, in the words of a CIA report prepared years later, “a staunch antagonist of oligarchical rule and a spellbinding orator.” He was also a shrewd politician who had turned his populist appeal into real political power. When the OAS conference convened in Bogotá in 1948, Gaitán was not only the people’s favorite, he was the head of the Liberal Party, one of the country’s two major political organizations. His election as president in 1950 was regarded as a virtual certainty. Yet the Conservative Party government, headed by President Ospina, had left Gaitán off the bipartisan delegation appointed to represent Colombia at the great conference.

Tensions were high in the city. Colombian historian German Arciniegas would later write of “a chill wind of terror blowing in from the provinces.” The day before the conference convened, a mob attacked a car carrying the Ecuadorian delegation, and rumors of terrorist violence seemed confirmed the same day when police caught a worker attempting to plant a bomb in the capital. In the midst of all the hubbub, Gaitán quietly went about his law practice. He knew his moment was still a few years off, and he was prepared to wait. The president’s snub had only enhanced his stature among his supporters, as well as among the more radical young leftists gathering to protest, who otherwise might have dismissed Gaitán as a bourgeois liberal with a vision too timid for their ambition. Castro had made an appointment to meet with him.

Gaitán busied himself with defending an army officer accused of murder, and on April 8, the day the conference convened, he won an acquittal. Late the next morning, some journalists and friends stopped by his office to offer congratulations. They chatted happily, arguing about where to go for lunch and who would pay. Shortly before one o’clock, Gaitán walked down to the street with the small group. He had two hours before the scheduled meeting with Castro.

Leaving the building, the group walked past a fat, dirty, unshaven man who let them pass and then ran to overtake them. The man, Juan Roa, stopped and without a word leveled a handgun. Gaitán briskly turned and started back toward the safety of his office building. Roa began shooting. Gaitán fell with wounds to his head, lungs, and liver, and died within the hour as doctors tried desperately to save him.

Gaitán’s murder is where the modern history of Colombia starts. There would be many theories about Roa—that he had been recruited by the CIA or by Gaitán’s conservative enemies, or even by Communist extremists who feared that their revolution would be postponed by Gaitán’s ascension. In Colombia, murder rarely has a shortage of plausible motives. An independent investigation by officers of Scotland Yard determined that Roa, a frustrated mystic with grandiose delusions, had nursed a grudge against Gaitán and had acted alone; but since he was beaten to death on the spot, his motives died with him. Whatever Roa’s purpose, the rounds he fired unleashed chaos. All hope for a peaceful future in Colombia ended. All those brooding forces of change exploded into El Bogotazo, a spasm of rioting so intense it left large parts of the capital city ablaze before spreading to other cities. Many policemen, devotees of the slain leader, joined the angry mobs in the streets, as did student revolutionaries like Castro. The leftists donned red armbands and tried to direct the crowds, sensing with excitement that their moment had arrived, but quickly realized that the situation was beyond control. The mobs grew larger and larger, and protest evolved into random destruction, drunkenness, and looting. Ospina called in the army, which in some places fired into the crowds.

Everyone’s vision of the future died with Gaitán. The official effort to showcase a new era of stability and cooperation was badly tarnished; the visiting foreign delegations signed the charter and fled the country. The leftists’ hopes of igniting South America’s new communist era went up in flames. Castro took shelter in the Cuban embassy as the army began hunting down and arresting leftist agitators, who were blamed for the uprising, but even a CIA history of the event would conclude that the leftists were as much victims as everyone else. For Castro, an agency historian wrote, the episode was profoundly disillusioning: “[It] may have influenced his adoption in Cuba in the 1950s of a guerrilla strategy rather than one of revolution through urban disorders.”

El Bogotazo was eventually quieted in Bogotá and the other large cities, but it lived on throughout untamed Colombia for years, metamorphosing into a nightmarish period of bloodletting so empty of meaning it is called simply La Violencia. An estimated two hundred thousand people were killed. Most of the dead were campesinos, incited to violence by appeals to religious fervor, land rights, and a bewildering assortment of local issues. While Castro carried off his revolution in Cuba and the rest of the world squared off in the Cold War, Colombia remained locked in this cabalistic dance with death. Private and public armies terrorized the rural areas. The government fought paramilitaries and guerrillas, industrialists fought unionists, conservative Catholics fought heretical liberals, and bandidos took advantage of the free-for-all to plunder. Gaitán’s death had unleashed demons that had less to do with the emerging modern world than with Colombia’s deeply troubled past.

Colombia is a land that breeds outlaws. It has always been ungovernable, a nation of wild unsullied beauty, steeped in mystery. From the white peaks of the three cordilleras that form its western spine to the triple- canopy equatorial jungle at sea level, it affords many good places to hide. There are corners of Colombia still virtually untouched by man. Some are among the only places left on this thoroughly trampled planet where botanists and biologists can discover and attach their names to new species of plants, insects, birds, reptiles, and even small mammals.

The ancient cultures that flourished here were isolated and stubborn. With soil so rich and a climate so varied and mild, everything grew, so there was little need for trade or commerce. The land ensnared one like a sweet, tenacious vine. Those who came stayed. It took the Spanish almost two hundred years to subdue just one people, the Tairona, who lived in a lush pocket of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta foothills. European invaders eventually defeated them the only way they could, by killing them all. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the Spanish tried without success to rule from neighboring Peru, and in the nineteenth century Simón Bolívar tried to join Colombia with Peru and Venezuela to form a great South American state, Gran Colombia. But even the great liberator could not hold the pieces together.

Ever since Bolívar’s death in 1830, Colombia has been proudly democratic, but it has never quite got the hang of peaceful political evolution. Its government is weak, by design and tradition. In vast regions to the south and west, and even in the mountain villages outside the major cities, live communities only lightly touched by nation, government, or law. The sole civilizing influence ever to reach the whole country was the Catholic Church, and that was accomplished only because clever Jesuits grafted their Roman mysteries to ancient rituals and beliefs. Their hope was to grow a hybrid faith, nursing Christianity from pagan roots to a locally flavored version of the One True Faith, but in stubborn Colombia, it was Catholicism that took a detour. It grew into something else, a faith rich with ancestral connection, fatalism, superstition, magic, mystery . . . and violence.

Violence stalks Colombia like a biblical plague. The nation’s two major political factions, the Liberals and Conservatives, fought eight civil wars in the nineteenth century alone over the roles of church and state. Both groups were overwhelmingly Catholic, but the Liberals wanted to keep the priests off the public stage. The worst of these conflicts, which began in 1899 and was called the War of a Thousand Days, left more than one hundred thousand dead and utterly ruined whatever national government and economy existed.

Caught between these two violent forces, the Colombian peasantry learned to fear and distrust both. They found heroes in the outlaws who roamed the Colombian wilderness as violent free agents, defying everyone. During the War of a Thousand Days the most famous was José del Carmen Tejeiro, who played upon popular hatred of the warring powers. Tejeiro would not just steal from wealthy landowning enemies; he would punish and humiliate them, forcing them to sign declarations such as “I was whipped fifty times by José del Carmen Tejeiro as retribution for persecuting him.” His fame earned him supporters beyond Colombia’s borders. Venezuelan dictator Juan Vicente Gómez, sowing a little neighborhood instability, presented Tejeiro with a gold-studded carbine.

A half century later, La Violencia bred a new colorful menagerie of outlaws, men who went by names like Tarzan, Desquite (Revenge), Tirofijo (Sureshot), Sangrenegra (Blackblood), and Chispas (Sparks). They roamed the countryside, robbing, pillaging, raping, and killing, but because they were allied with none of the major factions, their crimes were seen by many common people as blows struck against power.

La Violencia eased only when General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla seized power in 1953 and established a military dictatorship. He lasted five years before being ousted by more democratic military officers. A national plan was put in place for Liberals and Conservatives to share the government, alternating the presidency every four years. It was a system guaranteed to prevent any real reforms or government-initiated social progress, because any steps taken during one administration could be undone in the next. The famous bandidos went on raiding and stealing in the hills, and occasionally made halfhearted attempts to band together. In the end they were not idealists or revolutionaries, just outlaws. Still, a generation of Colombians grew up on their exploits. The bandidos were heroes despite themselves to many of the powerless, terrorized, and oppressed poor. The nation both thrilled and mourned as the army of the oligarchs in Bogotá hunted them down, one by one. By the 1960s Colombia had settled into an enforced stasis, with Marxist guerrillas in the hills and jungles (modern successors to the bandido tradition) and a central government increasingly dominated by a small group of rich, elite Bogotá families, powerless to effect change and, anyway, disinclined. The violence, already deeply rooted in the culture, continued, deepened, twisted.

Terror became art, a form of psychological warfare with a quasi- religious aesthetic. In Colombia it wasn’t enough to hurt or even kill your enemy; there was ritual to be observed. Rape had to be performed in public, before fathers, mothers, husbands, sisters, brothers, sons, and daughters. And before you killed a man, you first made him beg, scream, and gag . . . or first you killed those he most loved before his eyes. To amplify revulsion and fear, victims were horribly mutilated and left on display. Male victims had their genitals stuffed in their mouths; women had their breasts cut off and their wombs stretched over their heads. Children were killed not by accident but slowly, with pleasure. Severed heads were left on pikes along public roadways. Colombian killers perfected signature cuts, distinctive ways of mutilating victims. One gang left its mark by slicing the neck of a victim and then pulling his tongue down his throat and out through the slice, leaving a grotesque “necktie.” These horrors seldom directly touched the educated urbanites of Colombia’s ruling classes, but the waves of fear widened and reached everywhere. No child raised in Colombia at midcentury was immune to it. Blood flowed like the muddy red waters that rushed down from the mountains. The joke Colombians told was that God had made their land so beautiful, so rich in every natural way, that it was unfair to the rest of the world; He had evened the score by populating it with the most evil race of men.

It was here, in the second year of La Violencia, that the greatest outlaw in history, Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria, was born, on December 1, 1949. He grew up with the cruelty and terror alive in the hills around his native Medellín, and absorbed the stories of Desquite, Sangrenegra, and Tirofijo, all of them full-blown legends by the time he was old enough to listen and understand, most of them still alive and on the run. Pablo would outstrip them all by far.

Anyone can be a criminal, but to be an outlaw demands a following. The outlaw stands for something, usually through no effort of his own. No matter how base the actual motives of criminals like those in the Colombian hills, or like the American ones immortalized by Hollywood—Al Capone, Bonnie and Clyde, Jesse James—large numbers of average people rooted for them and followed their bloody exploits with some measure of delight. Their acts, however selfish or senseless, were invested with social meaning. Their crimes and violence were blows struck against distant, oppressive power. Their stealth and cunning in avoiding soldiers and police were celebrated, these being the time-honored tactics of the powerless.

Pablo Escobar would build on these myths. While the other outlaws remained strictly local heroes, meaningful only as symbols, his power would become both international and real. At his peak, he would threaten to usurp the Colombian state. Forbes magazine would list him as the seventh-richest man in the world in 1989. His violent reach would make him the most feared terrorist in the world.

His success would owe much to his nation’s unique culture and history, indeed to its very soil and climate, with its bountiful harvests of coca and marijuana. But an equal part of it was Pablo himself. Unlike any other outlaw before, he understood the potency of legend. He crafted his and nurtured it. He was a vicious thug, but he had a social conscience. He was a brutal crime boss but also a politician with a genuinely winning personal style that, at least for some, transcended the ugliness of his deeds. He was shrewd and arrogant and rich enough to milk that popularity. He had, in the words of former Colombian president César Gaviria, “a kind of native genius for public relations.” At his death, Pablo was mourned by thousands. Crowds rioted when his casket was carried into the streets of his home city of Medellín. People pushed the bearers aside and pried open the lid to touch his cold, stiff face. His gravesite is tended lovingly to this day and remains one of the most popular tourist spots in the city. He stood for something.

For what, exactly, isn’t easy to understand without knowing Colombia and his life and times. Pablo, too, was a creature of his time and place. He was a complex, contradictory, and ultimately very dangerous man, in large part because of his genius for manipulating public opinion. But this same crowd-pleasing quality was also his weakness, the thing that eventually brought him down. A man of lesser ambition might still be alive, rich, powerful, and living well and openly in Medellín. But Pablo wasn’t content to be just rich and powerful. He wanted to be admired. He wanted to be respected. He wanted to be loved.

When he was a small boy, his mother, Hermilda, the real shaping influence in his life, made a vow before a statue in her home village of Frontino, in the rural northwest part of the Colombian departamento, or state, of Antioquia. The statue, an icon, was of the child Jesus of Atocha. Hermilda Gaviria was a schoolteacher, an ambitious, educated, and unusually capable woman for that time and place, who had married Abel de Jesús Escobar, a self-sufficient cattle farmer. Pablo was their second son, and she had already borne Abel a daughter. They would eventually have four more children. But Hermilda was cursed with powerlessness. For all her learning and drive, she knew that the fates of her ambition and her family were out of her hands. She knew this not just in some abstract, spiritual way, the way religious men and women accept the final authority of God. This was Colombia in the 1950s. The horror of La Violencia was everywhere. Unlike the relatively secure cities, in villages like Frontino and the one where Hermilda and Abel now lived, Rionegro, violent and terrible death was commonplace. The Escobars were not revolutionaries; they were staunchly middle class. To the extent that they had political leanings, they were allied with local Conservative landowners, which made them targets for the Liberal armies and insurrectionists who roamed the hills. Hermilda sought protection and solace from the child Jesus of Atocha with the urgency of a young wife and mother adrift in a sea of terror. In her prayers she vowed something concrete and grand. Someday, she said, she would build a chapel for Jesus of Atocha if God spared her family from the Liberals. Pablo would build that chapel.

Pablo did not grow up poor, as he and his hired publicists would sometimes later claim. Rionegro was not yet a suburb of Medellín, but a collection of relatively prosperous cattle farms in the outlying districts. Abel owned a house, twelve hectares, and six cows when Pablo was born, and he tended adjacent land that he had sold to a well-known local Conservative politician. The house had no electricity but did have running water. For rural Colombia, this would qualify as upper middle class, and conditions improved when they moved to Envigado, a village on the outskirts of Medellín, a thriving city that was rapidly creeping up the green slopes of the mountains around it. Hermilda was not just a schoolteacher but a founder of Envigado’s elementary school. When they moved there, Abel gave up his farming to work as a neighborhood watchman. Hermilda was an important person in the community, someone well-known to parents and children alike. So even as schoolchildren, Pablo and his brothers and sisters were special. Pablo did well in his classes, as his mother no doubt expected, and he loved to play soccer. He was well dressed and, as his chubby frame attested, well fed. Escobar liked fast food, movies, and popular music—American, Mexican, and Brazilian.

While there was still violence in Colombia, even as he entered his teens, the raging terror of La Violencia gradually eased. Abel and Hermilda Escobar emerged from it all to create a comfortable life for themselves and their seven children. But just as the prosperity of the fifties in the United States bred a restless, rebellious generation of children, so Pablo and his contemporaries in Medellín had their own way of tuning in, turning on, and dropping out. A hippielike, nihilistic, countrywide youth movement called Nadaismo had its origins right in Envigado, where its founder, the intellectual Fernando Gonzáles, had written his manifesto “The Right to Disobey.” Banned by the church, barely tolerated by authorities, the Nadaistas—the “nothingists”—lampooned their elders in song, dressed and behaved outrageously, and expressed their disdain for the established order in the established way of the sixties: they smoked dope.

Colombian dope was, of course, plentiful and highly potent, a fact that the world’s marijuana-toking millions quickly discovered. It was soon the worldwide gold standard for pot. Pablo became a heavy doper early on and stayed that way throughout his life, sleeping until one or two in the afternoon, lighting up not long after waking up, and staying stoned for the rest of the day and night. He was plump and short, standing just under five feet, six inches, with a large, round face and thick, black, curly hair that he wore long, combing it left to right in a big mound that sloped across his forehead and covered his ears. He grew a wispy mustache. He looked out at the world through big, heavy-lidded hazel eyes and cultivated the bemused boredom of the chronic doper. Rebellion evidently took hold not long after he reached puberty. He dropped out of Lyceum Lucrecio Jaramillo several months before his seventeenth birthday, three years shy of graduation. His turn to crime appears to have been motivated as much by ennui as ambition.

With his cousin and constant companion Gustavo Gaviria, he had taken to hanging out nights at a bar in a tough neighborhood, the Jesús de Nazareno district. He told Hermilda that he wasn’t cut out for school or a normal job. “I want to be big,” he said. It was a testament to Hermilda’s persistence, or possibly Pablo’s broader plans, that he never fully abandoned the idea of education. He briefly returned to the lyceum two years later with Gustavo, but the two, older than their classmates and accustomed now to the freedom and rough-and-tumble of the Medellín streets, were considered bullies and were soon fighting with their teachers. Neither lasted the school year, although Pablo apparently tried several times, without success, to pass the tests needed to earn a diploma. He eventually just bought one. In later life he would fill shelves in his homes with stacks of unread classics and would talk sometimes of wanting to earn a higher degree. At one point, entering prison, he said he intended to study law. No doubt this lack of formal education continued to feed his insecurities and disappoint Hermilda, but no one who knew him doubted his natural cunning.

He became a gangster. There was a long tradition of shady business practices in Medellín. The stereotypical paisa was a hustler, someone skilled in turning a profit no matter what the enterprise. The region was famous for contrabandistas, local heads of organized-crime syndicates, practitioners of the centuries-old paisa tradition of smuggling—originally gold and emeralds, now marijuana, and soon cocaine. By the time Pablo dropped out of school, in 1966, drug smuggling was already serious business, well over the heads of seventeen-year-old hoodlums. Pablo got his start conning people out of money on the streets of Medellín. But he had plans. When he told his mother that he wanted to be big, he most likely had in mind two kinds of success. Just as the contrabandistas dominated the illicit street life of Medellín, its legitimate society was ruled politically and socially by a small number of rich textile and mining industrialists and landowners. These were the dons, the men of culture and education whose money bankrolled the churches and charities and country clubs, who were feared and respected by their employees and those who rented their land. Catholic, traditional, and elitist, these men held high public office and went off to Bogotá to represent Medellín in the national government Pablo’s ambition encompassed both worlds, licit and illicit, and this marks the central contradiction of his career.

The standing legend of Pablo Escobar has it that he and his gang got their start by stealing headstones from cemeteries, sandblasting them clean, and then reselling them. He did have an uncle who sold tombstones, and Pablo evidently worked for him briefly as a teenager. In later life he was always amused when the sandblasting stories were told, and he denied them—but then there was always much that Pablo denied. Hermilda has also called the story a lie, and, indeed, it doesn’t seem likely. For one thing, sandblasting sounds too much like honest labor, and there is little to suggest that Pablo ever had an appetite for that. And he was deeply superstitious. He subscribed to that peculiarly pagan brand of Catholicism common in rural Antioquia, one that prays to idols—like Hermilda’s child Jesus of Atocha—and communes with dead spirits. Stealing headstones would be an unlikely vocation for anyone who feared the spirit world. What sounds more likely are stories he later admitted to, of running petty street scams with his friends, selling contraband cigarettes and fake lottery tickets, and conning people out of their cash with a mixture of bluff and charm as they emerged from the local bank. Pablo would not have been the first street-smart kid to discover that it was easier and more exciting to take money from others than to earn it. He was exceptionally daring. Maybe it was the dope, but Pablo discovered in himself an ability to remain calm, deliberate, even cheerful when others grew frightened and unsteady. He used it to impress his friends, and to frighten them. On several occasions as a youth, Pablo later boasted, he had held up Medillín banks by himself with an automatic rifle, bantering cheerfully with the clerks as they emptied their cash drawers. That kind of recklessness and poise is what distinguished Pablo from his criminal peers and made him their leader. Before long his crimes would grow more sophisticated, and more dangerous.

The record shows that Pablo was an accomplished car thief before he was twenty. He and his gang took the crude business of pinching cars and turned it into a mini-industry, boldly taking vehicles (drivers would just be pulled from behind the steering wheel in broad daylight) and chopping them down to a collection of valuable parts within hours. There was plenty of money to be made in parts, and no direct evidence of the theft remained. Once he’d amassed sufficient capital, Pablo began simply bribing municipal officials to issue new papers for stolen vehicles, eliminating the need to disassemble the cars. He seems to have had few significant run-ins with the law during this period. The arrest records have vanished, but Pablo did spend several months in a Medellín jail before his twentieth birthday, no doubt making connections with a more violent class of criminals, who would later serve him well. Clearly the stint behind bars did nothing to dissuade him from a life of crime.

By all accounts, Pablo was enjoying himself. With their wide inventory of stolen engines and parts, he and Gustavo built race cars and competed in local and national car rallies. His business evolved. In time, car theft in Medellín was practiced with such impunity that Pablo realized he had created an even more lucrative market. He started selling protection. People paid him to prevent their vehicles from being pinched—so Pablo began making money on cars he didn’t steal as well as from those he did. Generous with his friends, he would give them new cars stolen right from the factory. Pablo would draw up false bills of sale and instruct the recipients to take out fake newspaper ads offering the cars for sale, creating a paper trail to make it appear as though the cars had been obtained legitimately.

It was during this period, as a young crime boss on the make, that Pablo developed a reputation for casual, lethal violence. In what may have begun as simply a method of debt collection, he would recruit thugs to kidnap people who owed him money and then ransom them for whatever was owed. If the family couldn’t come up with the money or refused to pay, the victim would be killed. Sometimes the victim was killed after the ransom was paid, just to make a point. It was murder, but a kind of murder that can be rationalized. A man had to protect his interests. Pablo lived in a world where accumulation of wealth required the capacity to defend it. Even for legitimate businessmen in Medellín there was little effective or honest law enforcement. If someone cheated you, you either accepted your losses or took steps yourself to settle the score. If you grew successful enough, you had to contend with corrupt police and government officials who wanted a piece of your profits. This was especially true in Pablo’s new illicit business. As the amounts of money and contraband grew, so did the need to enforce discipline, punish enemies, collect debts, and bribe officials. Kidnapping or even killing someone who had cheated him not only kept the books balanced; it sent a message.

Pablo became expert at taking credit for crimes that could not be linked to him directly. From the start, he made sure that those he recruited to commit violent acts were never certain who had hired them. In time, Pablo grew accustomed to ordering people killed. It fed his growing megalomania and bred fear— which was akin to the respect he seemed to crave more and more.

Kidnapping for debt collection evolved soon enough into kidnapping for its own sake. The most famous case attributed to young Pablo was that of Envigado industrialist Diego Echavarria, in the summer of 1971. Echavarria was a proud Conservative factory owner, widely respected in higher social circles but disliked by many of the poor workers in Medellín, who were being laid off in droves from local textile mills. At the time, wealthy Antioquia landowners were expanding their country holdings by simply evicting whole villages of farmers from the Magdalena River Valley, leaving them no alternative but to move to the slums of the growing city. The unpopular factory owner’s body was found in a hole not far from the place where Pablo was born. He had been kidnapped six weeks earlier and had been beaten and strangled, even though his family had paid a $50,000 ransom. The killing of Diego Echavarria worked on two levels. It turned a profit and it doubled as a blow for social justice. There is no way to prove that Pablo orchestrated this crime, and he was never officially charged with it, but it was so widely attributed to him that in the slums people began referring to Pablo admiringly as Doctor Echavarria, or simply El Doctor. The killing had all the hallmarks of the young crime boss’s emerging style: cruel, deadly, smart, and with an eye toward public relations.

In one stroke, the Echavarria kidnapping elevated Pablo to the status of local legend. It also advertised his ruthlessness and ambition, which didn’t hurt either. In coming years, he would become even more of a hero to many in Medellín’s slums with well-publicized acts of charity. He had a social conscience, but his aspirations were strictly middle class. When he told his mother he wanted to be “big,” he wasn’t dreaming of revolution or remaking his country; he had in mind living in a mansion as spectacular as the mock medieval castle Echavarria had built for himself. He would live in a castle like that, not as someone who exploited the masses but as a people’s don, a man of power and wealth who had not lost touch with the common man. His deepest anger was always reserved for those who interfered with that fantasy.

2

Pablo Escobar was already a clever and successful crook when a seismic shift in criminal opportunity presented itself in the mid-seventies: the pot generation discovered cocaine. The illicit pathways marijuana had carved from Colombia to North American cities and suburbs became expressways as coke became the fashionable drug of choice for adventurous young professionals. The cocaine business would make Pablo Escobar and his fellow Antioquia crime bosses—the Ochoa brothers, Carlos Lehder, José Rodríguez Gacha—and others richer than their wildest fantasies, among the richest men in the world. By the end of the decade they would control more than half of the cocaine shipped to the United States, netting a return flow measured in not millions but billions of dollars. Their enterprise became the largest industry in Colombia, and bankrolled the candidacies of mayors, councilmen, congressmen, and presidents. By the mid-eighties, Escobar would own nineteen different residences in Medellín alone, each with a heliport. He owned fleets of boats and planes, properties throughout the world, large swaths of Antioquian land, apartment complexes, housing developments, and banks. There was so much money rolling in that figuring out how to invest all of it was more than they could handle; many millions were simply buried. The flood of foreign cash triggered good times in Medellín. There was a boom in construction and new business start-ups, and unemployment plummeted. Eventually, the explosion of drug money knocked the entire country of Colombia off balance and upended the rule of law.

Pablo was perfectly positioned to take advantage of this wave. He had spent more than a decade building his local criminal syndicate and learning the ways of bribing officialdom. The cocaine boom initially attracted amateurs for whom cocaine was a glamorous flirtation with crime. But crime was already Pablo’s element. He was violent and unprincipled, and a determined climber. He wasn’t an entrepreneur, and he wasn’t even an especially talented businessman. He was just ruthless. When he learned about a thriving cocaine-processing lab on his turf, he shouldered his way in. If someone developed a lucrative delivery route north, Pablo demanded a majority of the profits—for protection. No one dared refuse him.

A young Medellín pilot who went by the nickname “Rubin,” and whose skills naturally led him into the cocaine business during those years, met Pablo for the first time in 1975. Rubin had grown up in a well-to-do family that had sent him to the United States to get an education. He had earned his pilot’s license in Miami, and he spoke English fluently. When some of his friends, the Ochoa brothers, Alonzo, Jorge, and Fabio, started shipping cocaine north, Rubin fell easily into the business with them. Before long he was buying and selling small planes in Miami, recruiting pilots to make the low-level flights. Rubin and the Ochoas were not professional tough guys, like Pablo and his gang, but playboys, relatively well educated young Colombians who considered themselves fashionable and smart. Very soon they were also rich.

Their very stylishness is what enabled them to ship and move cocaine, not any genius for business or connections with Antioquia’s criminal class. They were comfortable in the upscale social circles in Miami where American buyers congregated. Rubin was perfect. He was handsome, fearless, even dashing. His boss at the time was a Medellín entrepreneur named Fabio Restrepo, one of the first paisa cocaine chiefs. In 1975 Restrepo was pulling together shipments of forty to sixty kilos of cocaine once or twice a year—and a kilo would sell for more than $40,000 in Miami. Whenever that much money is being made illegally, it attracts sharks.

Pablo originally contacted Jorge Ochoa to see about selling Restrepo some uncut product. Rubin accompanied Jorge to a small apartment in Medellín, where they were met at the door by a chubby young man with a thick mop of curly black hair who strutted alongside them comically, like a typical street tough. He wore a big pullover polo shirt, blue jeans that were rolled up at the cuff, and tennis shoes, and the apartment where they met him was a sty, strewn with trash and discarded clothing. To these two rich young dandies, Pablo was nothing but a local hoodlum. The fourteen kilos of cocaine he showed them in a dresser drawer was strictly small-time. They bought the cocaine from him and moved on, unimpressed—until Restrepo was murdered two months later. It was shocking. Somebody had simply killed him! And, just like that, there was a new man in charge of the cocaine business in Medellín. Rubin and the Ochoa brothers were surprised, after Restrepo’s death, to find that they were now working for Pablo Escobar. There was, of course, no way to prove that Pablo had killed Restrepo, but he didn’t seem to mind if people drew that conclusion. The playboy cocaine traffickers had underestimated the local hoodlum. The low-class, strictly small-time dealer had brutally and efficiently muscled his way in.

“There was not a single aspect of the business that was created, designed, or promoted by Pablo Escobar,” Rubin says. “He was a gangster, pure and simple. Everybody, right from the start, was afraid of him. Even later, when they considered themselves friends, everybody was afraid of him.”

In March 1976, Pablo married Maria Victoria Henao Vellejo, a shapely, pretty, dark-haired fifteen-year-old, so young that Pablo had had to obtain a special dispensation from the bishop (such things could be had for a fee). At age twenty-six, married, wealthy, and feared, if not respected, Pablo was on his way to achieving his dreams. But his rapid rise had already earned him dangerous enemies. One of them tipped off agents of the DAS (Departamento Administrativo de Seguridad), who arrested Pablo, his cousin Gustavo, and three other men, just two months after the wedding, as they returned to Medellín from a drug run to Ecuador.

Pablo had been arrested before. There was that stint he’d done at Itagui as a teenager, and he had been arrested again in 1974, caught in a stolen Renault. Both times he had been convicted and sentenced to serve several months in prison. But this was far more serious. The DAS agents found thirty-nine kilos of cocaine hidden in the spare tire of the group’s truck, enough to place them in the big league of coke smuggling at that time, and to send them all to prison for a long time.

Pablo tried bribing the judge, who turned the money down flat. So the judge’s background was researched, and it was learned that he had a brother who was a lawyer. The two brothers did not get along, and the lawyer agreed to represent Pablo in the case, knowing that the judge would likely recuse himself as soon as he found out, which is what happened. The new judge was more amenable to bribery, and Pablo, his cousin, and the others were freed. The maneuver had been so bold that an appellate judge, just months later, reinstated the indictments and ordered Pablo and the others rearrested. But further appeals tied up the case, and in March of the following year, with Pablo still at large, the two DAS agents responsible for the arrest—Luis Vasco and Gilberto Hernandez—were killed.

Pablo was establishing a pattern of dealing with the authorities that would become his trademark. It soon became known simply as plata o plomo. One either accepted Pablo’s plata (silver) or his plomo (lead).

None of the party boys in Medellín were complaining much about Pablo’s methods, because they were all getting rich. Pablo absorbed the entrepreneurs, the lab rats, and the distributors like the Ochoas. He “insured” them. He oversaw their delivery routes, exacting a tax on every kilo shipped. It was pure muscle, an old-fashioned syndicate, but the result was to create for the first time a unified and streamlined cocaine industry. Once the coca leaves had been grown and refined by independent dealers, their shipments would be added to the loads controlled by Pablo’s organization, a service for which they paid 10 percent of the wholesale U.S. price. If a big shipment was intercepted or lost, Pablo would repay his suppliers, but only for what the load had cost in Colombia. If only one or two shipments made it to Miami, New York, or Los Angeles, the sale would more than cover the cost of four or five lost or intercepted loads—and drug enforcement efforts were intercepting fewer than one load in ten. Losses were always far exceeded by profits.

And what profits. The appetite for white powder in America was seemingly inexhaustible. More money than anyone in Medellín had ever dreamed of seeing, money enough to remake not just lives but whole cities, whole nations! Between 1976 and 1980 bank deposits in Colombia’s four major cities more than doubled. So many illegal American dollars were flooding the country that the country’s elite began looking for ways to score its share without breaking the law. President Alfonso López Michelsen’s administration permitted a practice that the central bank called “opening a side window,” which allowed unlimited quantities of dollars to be converted to Colombian pesos. The government also encouraged the creation of speculative funds that offered exorbitantly high interest rates. These were ostensibly legitimate investments in highly speculative markets, but nearly everyone knew that their money was really being invested in shipments of cocaine. The government played along by turning a blind eye. Soon anyone with money to invest in Bogotá could readily cash in on the drug bonanza. The whole nation wanted to join Pablo’s party.

With his millions, Pablo could now afford to buy protection for his cocaine shipments all through the pipeline, from growers to processors to distributors. He began traveling to Peru, Bolivia, and Panama, buying up control of the enterprise from top to bottom. He wasn’t the only one. The Rodríguez Orejuela brothers, Jorge, Gilberto, and Miguel, were pulling together the threads of the Cali cocaine cartel at the same time. Competing in Antioquia—and sometimes collaborating—were José Rodríguez Gacha and the eccentric half German Carlos Lehder. Pablo’s payoffs went from thousands to millions of pesos (hundreds of thousands of dollars), and there were few law-enforcement officials inclined to resist the juggernaut—especially when one considered the alternative. Pablo was even willing to play along a little, allowing a few shipments to be intercepted, enough to make law enforcement look like it was doing its job. He could afford it. Nobody had a good handle on how much cocaine was flowing north. The estimates tended to be low by a factor of ten or more. American officials were estimating total shipments of five to six hundred kilos a year in 1975 when police in Cali stumbled over six hundred kilos in a single airplane. The seizure triggered a weekend war in Medellín, where various factions accused the others of either screwing up or selling out. Forty people were killed. But shipments of that size had become routine, and the vast majority of it got through. The tide of corruption and drug money simply swept away the relatively flimsy organs of law and authority. It happened so quickly that officials in Bogotá hardly noticed.

After skating away from his drug bust in 1976, Pablo knew he had little to fear from the law in Medellín. He was the unofficial king of the city. Rubin was in Miami during this period, so for a few years he didn’t see Pablo or his friends the Ochoas. When he returned to Colombia in 1981, as he puts it, “The circus was in full swing.” All of the cocaine kings had mansions, limousines, race cars, personal helicopters and planes, fine clothes, and fancy artwork (some, like Pablo, hired decorators to guide their taste in painting and sculpture, which tended toward the garish and surreal). They were surrounded by bodyguards, sycophants, and women, women, women. It was a higher life than anyone in Colombia had ever seen, and it was going to go higher still. The gangsters imported a nightlife to Medellín, opening lavish discos and fine restaurants.

Pablo in particular was known for his adolescent appetites. He and his buddies would play soccer matches under the lights on fields that he had paid to have leveled and sodded, paying announcers to call their amateur games as though they were big-time professional matches. Opponents and teammates were always careful to make Don Pablo look good. Soon he and the other cocaine kingpins would buy the best soccer clubs in the country. To entertain his closest friends, Pablo would hire a gaggle of beauty queens for evenings of erotic games. The women would strip and race naked toward an expensive sports car, which the winner would keep, or submit to bizarre humiliations—shaving their heads, swallowing insects, or engaging in naked tree-climbing contests. In the bedroom of one residence he kept, apparently for recreational purposes, a gynecological examination chair. In 1979 he constructed a lavish country estate on a seventy-four-hundred-acre ranch near Puerto Triunfo on the Magdalena River, about eighty miles east of Medellín. He called it “Hacienda Los Nápoles.” The land alone cost him $63 million, and he had just started spending. He built an airport, a heliport, and a network of roads. He flew in hundreds of exotic animals—elephants, buffaloes, lions, rhinoceroses, gazelles, zebras, hippos, camels, and ostriches. He built six different swimming pools and created several lakes. The mansion was outfitted with every toy and extravagance money could buy. Pablo could sleep a hundred guests at a time, and entertain them with food, music, games, and parties. There were billiard tables and pinball machines, and a Wurlitzer jukebox that featured the records of Pablo’s favorite performer, Brazilian singer Roberto Carlos. On display out front was a thirties-era sedan peppered with bullet holes, which Pablo said had belonged to Bonnie and Clyde. He would take his guests on jarring trail-bike excursions across his estate, or race them on Jet Skis across one of his custom lakes. Nápoles was an outrageous blend of the erotic, exotic, and extravagant. Pablo was its maestro. He enjoyed speed, sex, and showing off, and he craved an audience.