9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

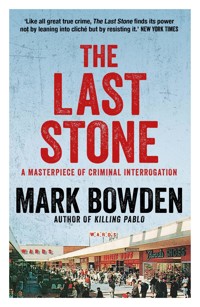

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

From the bestselling author of Killing Pablo, a haunting and gripping account of the true-life search for the perpetrator of a hideous crime-the abduction and likely murder of two young girls in 1975-and the skilful work of the cold case team that finally brought their kidnapper to justice. On March 29, 1975, sisters Kate and Sheila Lyon, aged ten and twelve, disappeared during a trip to a shopping mall in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. Three days later, eighteen-year-old Lloyd Welch visited the Montgomery County Police headquarters with a tip: he had seen the Lyon girls at the mall that day and had watched them climb into a strange man's car. Welch's tip led nowhere, and the police dismissed him as a drug-addled troublemaker wasting their time. As the weeks passed, and the police's massive search for the girls came up empty, grief, shock and horror spread out from the Lyon family to overtake the entire region. The trail went cold, the investigation was shelved and hope for justice waned. Then, in 2013, a detective on the department's cold case squad reopened the Lyon files and eventually discovered that the officers had missed something big about Lloyd Welch in 1975. In 1975, at age 23, Mark Bowden was a rookie reporter for a small Maryland newspaper reporting on the Lyons sisters' disappearance. In The Last Stone, Bowden returns to his first major story, taking us behind the scenes of the cold case team's exceptional interrogation of Lloyd Welch, the man who - nearly forty years after the crime - quickly became the most likely suspect in the Lyon case. Based on extensive interviews and video footage from inside the interrogation room, The Last Stone is a thrilling and revelatory reconstruction of a masterful investigation.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Also by Mark Bowden

Doctor Dealer

Bringing the Heat

Black Hawk Down

Killing Pablo

Finders Keepers

Road Work

Guests of the Ayatollah

The Best Game Ever

Worm

The Finish

The Three Battles of Wanat

Hue 1968

First published in the United States of America and Canada in 2019 by Grove Atlantic

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © Mark Bowden, 2019

Maps copyright © Matt Ericson, 2019

The moral right of Mark Bowden to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Photo credits are as follows: p. 1: Montgomery County Police; p. 8: the Washington Post; p. 29: Montgomery County Police; p. 65: Photo by James K. Atherton / the Washington Post via Getty Images; p. 91: Photo by Ricky Carioti / the Washington Post via Getty Images; p. 115 Montgomery County Police; p. 134: (Left) Montgomery County Police (Right) WDBJ News; p. 155: © Jay Westcott / The News & Advance; p. 192: Montgomery County Police; p. 217 © Neal Augenstein / WTOP; p. 243 Montgomery County Police; p. 280 Montgomery County Police; p. 305: Photo by Sarah L. Voisin / the Washington Post via Getty Images; p. 341: Family photos via the Washington Post.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN 978 1 61185 631 6

Export trade paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 486 2

E-book ISBN 978 1 61185 914 0

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press, UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

To Gail

It’s a good deal like chess or boxing. Some people you have to crowd and keep off balance. Some you just box and they will end up beating themselves.

—Raymond Chandler

Most of the of the dialogue in this book was recorded.

I have edited it for concision and clarity.

1

The First Lie

Lloyd Lee Welch, 1977

APRIL 1, 1975

Lloyd Welch got himself good and high before he went back to Wheaton Plaza on April Fools’ Day. He was stoned enough not to listen when his stepmom, Edna, warned him, “Don’t get mixed up in this.”

But Lloyd was already mixed up in it, enough to scare him. He needed to do something, even if it meant running a big risk. The marijuana buzz, he figured, would soothe him and help him think straight. Such was his teenage logic.

Screwing up came naturally. He was a seventh-grade dropout with, at age eighteen, a pathetic whisper of a mustache. His long, thick dark brown hair was parted in the middle, strapped down with a headband. He was scrawny and acned and mean; life had treated him harshly, and it showed. And, man, could he talk. Lloyd was a con artist. Words tumbled from him pell-mell, as if their sheer number and urgency could persuade. Whatever was true in what he said came wrapped in slippery layers of guile.

The story Lloyd planned to tell that day concerned two little girls who had gone missing from Wheaton Plaza a week earlier—Sheila and Kate Lyon. Their disappearance had created a media storm. Every newspaper and TV and radio station between Richmond and Baltimore was reporting on the hunt. Children were on lockdown. The Lyon girls’ father, John, was a local radio personality, and this gave the crisis even more notoriety. After a week, past the point where odds favored ever finding the girls alive, the police in Montgomery County, Maryland, were desperate. The public had flooded them with tips, none of which had helped. The girls had vanished. In the days since their disappearance, both had had birthdays; Sheila had turned thirteen, and Kate, on Easter Sunday, eleven. The heart of every parent ached.

The plaza was a Main Street of sorts for the suburban sprawl northwest of Washington, DC. An enormous cross-shaped structure that had opened eight years earlier, it had stores on both sides of two partly sheltered promenades. The longer of the two was anchored at its ends by the department stores Montgomery Ward and Woodward & Lothrop; it had a roof open to the sky along the center and was ornamented at intervals with bush-filled brick planters, the sides of which doubled as seating areas. Where the two promenades intersected was a square with a fountain and a modernist sculpture, then decorated for Easter. The mall’s style was futuristic, with the long horizontal lines, sharp angles, and neon hues that artists and filmmakers associated with the space age. It was more than a place to shop; it was a social center, a place to see and be seen. Unlike traditional small towns, few of the residential communities that sprouted outside big cities in the 1950s had anything like a nucleus. So the mall filled a need beyond commerce, and like those being built in suburbs all over America, Wheaton Plaza was an immediate and enduring sensation. A towering sign above its vast parking lot spelled out its name, each huge black letter set in a giant orange ball that glowed at night. There were specialty shops, a three-screen cinema, a Peoples drugstore, and plenty of food outlets, including a Roy Rogers, an ice cream shop, and a popular pizza joint called the Orange Bowl. With schools out for spring break, unseasonably warm weather, and sunshine, the plaza was a magnet, especially for children.

Lloyd walked in by himself, looking for a security guard. His plan was to tell his story to a mall cop and leave, but he had a poor sense of situation. Any scrap of new intelligence about the Lyon sisters at that point was a very big deal. The mall cop immediately called the police. “Now I’m screwed,” Lloyd thought. “My stepmom was right.” Two detectives, Steve Hargrove and Mike Thilia, came promptly. Lloyd was taken to police headquarters, and as soon as a tape recorder was turned on, he did what he did best.

He told them he was twenty-two. He said he had finished high school. He had been at the mall with his wife, Helen. None of this was true. He had seen two little girls who fit the Lyon sisters’ description—the same ages, blond hair, the elder one (Sheila) with glasses—talking in the mall to an older man with a tape recorder. All of this was unremarkable; pictures of the girls had been everywhere, on TV, in newspapers, and on telephone poles—the police had posted thousands of leaflets. The unknown “tape recorder man” had been widely reported as the prime suspect. Lloyd offered a detailed description: hair gray around the ears, black and thick on top; a dark, stubbly face—“like a heavy shaver”—about six one, six two; wearing a brown suit, white shirt, and black tie; and carrying a brown briefcase that held the portable recorder. He said he’d overheard the man explaining to the girls that he recorded people’s voices and then put them on the radio. This same story had been in all the news reports and was known by just about everyone breathing within a radius of two hundred miles. Lloyd said he later saw both girls leaving the mall with the man and had seen them again outside as they drove off.

“All right, let me ask you a couple of questions before we get to the second time you saw him,” said Hargrove. “What brought your attention to the man and the little girls in the first place?”

“Well, because an older man talking to two small girls, just walk up and talk to them, the girls wouldn’t know exactly what to say if he was asking some kind of questions,” Lloyd said, words spilling out awkwardly. “And the girls looked pretty young, [one] about twelve, the other ten, a little younger than that maybe. I’m not sure how old they were, because I didn’t see their face[s], and they just caught my attention when he said he was putting them on the air, and he looked pretty old to be talking to someone that young”—as if it were uncommon for adults to speak with children.

“Did he appear to be alone?”

“Yes, he was alone.”

“Working by himself?”

“Right, until he started talking to those two girls.”

Lloyd said he saw the man pull the tape recorder out and show it to the girls, and that he himself watched them for five or ten minutes, which is a long time to sit and watch three strangers.

“I was sitting down at the time because I was walking around so much I was tired, and I sat down and that’s when I saw him talking to them.” He said he had been walking around the mall applying for jobs.

“Did you hear him ask the girls any specific questions?” Hargrove asked.

“Not at the time I was there, no. I didn’t hear that.”

“Did you hear the girls say anything?”

“One of the girls laughed, you know. Giggled, like.”

“Which one? The taller one?”

“The taller one.”

Lloyd was a fount of particulars about the girls’ departure.

“I came through the Peoples drugstore, and he was standing there, and they were getting ready to cross the street. Me and my wife, we both, she came and got me, and we cut through the store and we got in the car, and he left before us and he went west on University [Avenue], and we went west toward Langley Park. And the car that he got into was a red Camaro, and it had white seats, lining, and the girls had gotten in the back, and he got in the front, and there was a dent in the right rear end, and the taillight was busted out.”

“How did you know the taillight was busted out?”

“Because when he started to pull off, then he stepped on the brakes easy, and his taillight didn’t go on, just one of them.”

“Which one went on? Which side?”

Lloyd said the left-side light came on, the right side was broken, and then went on to offer a startling spate of additional details about the car—oversize shocks, high suspension, wide tires, chrome wheel covers—“and he had pinstripes on each side, and they were about one inch apart and they were black, and he had something written like an advertisement thing in the right-hand corner.”

“The front?”

“The back of the windshield. And it looked like it was on the outside or inside, I couldn’t really tell, and then his mufflers sounded really loud, and I noticed they sounded like glasspack mufflers, and he had square coming out, you know the muffler which at the end was a square, and I told my wife, Helen, I said, ‘Ain’t that a nice car, a souped-up car?’ and she said, ‘uh,’ she wasn’t paying that much attention to it. She was really tired from walking around so much and looking for a job, so she didn’t pay much attention. I don’t know if she saw the car or not. And we were pulling out, and he was right in front of us, and we were at the light and we stopped, and the light turned green, and I wasn’t really looking at the car when the light turned green, when he took off, that’s what got me to look again, because I was listening to the muffler and talking to her, and then he went west. And we went toward Langley Park, and that was the last time I had seen him since.”

“Why didn’t you come forward with this information when you first heard about it?”

“Because I wasn’t really positive and sure if it was the same guy and the same two girls at the time, and that’s why I was up in Wheaton Plaza today, looking at the picture and listening around to see if it was the same two girls and the same guy, and then I saw a captain, he was a security guard, and he remembered me there last Tuesday in a brown fur jacket.”

“You were wearing a brown fur jacket?”

“Yeah, I was wearing a brown fur jacket, and he talked to me again today. I mean, he didn’t talk to me last week, but he talked to me, and I told him about what I saw. That’s when he contacted you all. That’s when you got ahold of me.”

Lloyd said he might be able to identify the girls and the man if he saw them again. He could describe what the weather was like that earlier afternoon: “A little windy, but it was nice.” He said the Camaro had white Maryland tags.

“Okay, Lloyd, are you telling me, the police department, all this of your own free will?”

“Yes, I am.”

“No one has asked you?”

“No. I came forward of my own free will because I have been worried about the girls, even though I don’t know them, but I just can’t stand to see anybody hurt, two little girls, or anybody hurt.”

Hargrove and Thilia warned him that giving a false statement to the police was a criminal offense.

“Now, with that in mind, are you willing to say everything you told us is correct?” asked one of the officers.

“Yes, I am. I am telling you the truth. I can’t afford to lie because I have a baby on the way and a wife to take care of, and I can’t afford to lie about anything.”

“Are you nervous right now?”

“I am a little nervous talking to the tape recorder, yes.”

In a final flourish, Lloyd added that the man he saw leaving with the girls “walked with a little limp.”

Lloyd was then given a lie detector test, which he flunked. Flustered, he admitted that he’d made up everything about the car and about seeing the tape recorder man with the girls outside the mall. He had told them nothing that anyone listening to news reports wouldn’t know, gussied up with a peculiar flurry of made-up particulars. Lloyd thought for sure he’d be arrested then, but instead the detectives dismissed him, no doubt annoyed.

The officers missed something about Lloyd Welch that day, something big. Days earlier, Danette Shea, a girl slightly older than Sheila Lyon, who had seen Sheila at the mall that day, had described a man who had been following and staring at Danette and her friends. He had been so obnoxious that one of the girls had taunted him: “Why don’t you take a picture? It’ll last longer.” Shea had described the man as eighteen or nineteen years old, five eleven to six foot, dark brown hair in a shag, medium mustache. A police artist had even produced a sketch, which was in the growing file. It looked a lot like Lloyd.

Before leaving, Lloyd was given a lecture about lying to the police. He was enormously relieved. The Montgomery County police were swimming in useless tips just then. Given the urgency of the situation, the kid wasn’t just a nuisance, he was a serious waste of time. They had no doubt sized him up as a local knucklehead, obviously high, trying to insinuate himself into the story, play the hero, and collect a reward—WMAL, the radio station that employed John Lyon, had just upped its offering to $14,000, and the Wheaton Plaza Merchants’ Association had put up $5,000 more. Lloyd seemed stupid, not suspicious. How much sense would it make, after all, for someone involved with a kidnapping to draw attention to himself by claiming to be a witness and telling an elaborate lie? The six-page typed transcript of the interview went into a ring binder with all the other stray bits. A one-page report was written up. At the top, Hargrove wrote, “LIED.”

After that, the department didn’t give Lloyd Welch a second thought.

Not for thirty-eight years.

2

Finding Lloyd

John and Mary Lyon, 1975

ONE SHOT

One shot was all they were likely to get with Lloyd Welch. So the Mont-gomery County Police Department’s Lyon squad had gamed the meeting for months, all through the summer and fall of 2013. They had even driven down to Quantico, Virginia, to consult with FBI behavioral analysts, who drew up impressive charts and summoned comparative data to pronounce Lloyd a classic hard case. The analysts predicted he would clam up as soon as he learned what the squad wanted to ask him about.

At that point all they knew about Lloyd Lee Welch came from files. His criminal record sketched a rough time line before and after he had walked into Wheaton Plaza in 1975 with his bogus story—or so it had been considered then; now the authorities were less certain.

Lloyd’s record traced a heroic trail of malfeasance. In Maryland: larceny (1977), burglary (1981), assault and battery (1982). In Florida: burglary in Orlando (1977), burglary in Miami (1980). In Iowa: robbery in Sioux City (1987). Then he’d moved to South Carolina: public drunkenness and then grand larceny in Myrtle Beach (1988), burglary in Horry County (1989), sexual assault on a ten-year-old girl in Lock-hart (1992), drunk driving in Clover (1992). Then on to Virginia: sexual assault on a minor in Manassas (1996), simple assault in Manassas (1997). He’d finally landed hard in Delaware: sexual assault of a ten-year-old girl in New Castle (1997). After that the list ended. This was typical. Waning hormones or better judgment often overtook even the slowest learners by their mid-thirties, after which they avoided trouble. Either that or they got killed or locked up. In Welch’s case it was the latter. He was deep into a thirty-three-year sentence for the Delaware charge, housed at the James T. Vaughn Correctional Center in Smyrna.

All that interested the squad, however, was the story he’d told in 1975. Here was a potential eyewitness, albeit a sticky one, to the kidnapping of Sheila and Kate Lyon. He had failed every part of that old polygraph except his claim to have been in Wheaton Plaza at the same time the girls had disappeared, which was the part that most interested the detectives. If he had seen the girls with their abductor, he might be able to corroborate, all these years later, evidence against the squad’s prime suspect, a notorious pedophile and murderer named Ray Mileski.

But Welch’s own history with little girls made them wonder. Could he have been involved? Did he know Mileski? Welch was under no obligation to talk and had every reason not to. For a convicted pedophile, the slightest link to the Lyon case might mean serious trouble. Any attorney worth retaining would advise him to stay silent. On the other hand, showing some willingness to help with an old case might earn him grace down the line with the Delaware parole board. It was a delicate situation. To prepare, the detectives had talked with several members of Welch’s family, few of whom seemed to know him well. Those who did remembered him with grudging kinship and scorn. The detectives didn’t know what to expect and weren’t sure how to proceed. At weekly staff meetings, their captain kept asking, “When are you guys going to do this?” But with only one shot, they weren’t going to just wing it. Thirty-eight years after the girls vanished, Welch was the last stone unturned. The two biggest questions they wanted answered were, in order: Could he identify Mileski? Had they worked together?

From Montgomery County police headquarters in Gaithersburg to Delaware was a two-hour drive. The investigators bypassed Annapolis; crossed the long, high Chesapeake Bay Bridge; and then eased into the flat farmland of the Eastern Shore. Fields of brittle, head-high brown corn lined both sides of Highway 301. As he drove, Sergeant Chris Homrock talked last-minute strategy in the front with Montgomery County deputy state’s attorney Pete Feeney. In the back was Detective Dave Davis, the one who would actually be in the room with Welch. At the Dover, Delaware, police headquarters, to which Welch had been brought from the prison that morning, they would be joined by an FBI agent.

Moving Welch to the police station was part of their strategy. Prisoners did not like to be seen talking to cops, and there were eyes and ears everywhere in a maximum-security prison. It had taken high-level persuasion to get Delaware’s corrections department to agree. This would be Welch’s first trip to the outside world in years. But he might become eligible for work release in just two years, and with freedom on his horizon the drive south from Smyrna might give him a taste of it and encourage helpfulness. They knew his instincts would make him wary. In an inmate’s world, an unscheduled summons from the Law rarely meant good news.

Welch had not been told who wanted to see him or why. The squad wanted to catch him cold. First reactions were often revealing. Could the detectives get him talking? Lloyd would see the danger, so they had to entice him. But with what? He was under Delaware’s supervision, and they had no sway with that state’s prison system or parole board. With no carrot, they needed a stick, a way to convince Welch that it was more dangerous to stay silent than to talk. With nothing to hold over him, leverage would have to be invented.

The longer they’d planned for this day the less likely it seemed they would succeed. Spooking Welch was just their first worry. If he agreed to talk, how should they proceed? Should they read him his Miranda rights, or would that alarm him? If they didn’t and he incriminated himself, they couldn’t use his evidence. Should they tell him about Mileski? Their theory of the case? How much? How little? If he balked, how could they keep him in the room?

As the sergeant and prosecutor rehashed these questions in the car, Dave Davis clapped on earphones and tuned them out. He watched the flat farmland fly past. They weren’t going to come up with anything new. Dave was a wiry, boyish-looking man with an engaging, toothy smile. His close-cropped dark hair was beginning to show flecks of gray, but he still wore it spiked in front like a teenager, and he was always meticulously groomed—his colleagues teased him about it. Even when he was dressed informally, as was his norm, his slacks and sport shirts were spotless and unwrinkled. His weekend passion for extreme mountain biking kept him tan and very fit. After graduating from Florida Southern College with a criminology degree, he had worked for his father’s heating and air-conditioning company before becoming a cop, and he still supplemented his paycheck with carpentry and general contracting. He liked his job, but for him, unlike many of his colleagues, it was just a job, not his mission in life. When asked what he did for a living, Dave would answer, “I work for local government,” because if he said he was a cop, the mood instantly stiffened. As Dave saw it, the work was what he did, not who he was. He came from a military family and as a teenager had seriously considered West Point or the US Naval Academy—he was a good athlete, which would have helped—but he had decided against military service because it was too defining. Being a civilian—“a regular guy,” as he put it—was a conscious choice. Many of the cops he knew found ways to moonlight in work related to policing—security work or consulting—but Dave did not. He preferred time away from it. Off duty, he liked himself better. That didn’t mean he took the job less seriously; in fact, it made him better at it. People didn’t see Dave as a cop; they saw him as just a friendly, outgoing guy, but this sunny demeanor hid a quick, calculating mind.

Chris considered him the best interrogator in the department. It was work that particularly suited Dave. Criminals saw the man, not the badge, and they liked him, sometimes enough to tell him surprising and damaging things. As one of his colleagues put it, “Dave is very genuine, even when he isn’t genuine.” The department had nabbed a gang of armored-car robbers after a string of violent, sophisticated heists—in which the gang had stolen hundreds of thousands of dollars at a time. The ringleader, a man with an extensive record that included murder, had, at the end of a long conversation with Dave, not only confessed but also told him where the loot was buried. They dug it up at two in the morning on a golf course in Howard County, right where he’d said it would be. Years later Chris was still amazed by that. He didn’t understand how it had happened. He just knew that when they met Lloyd Welch, he wanted Dave to be the man in the room.

The earphones bought Dave some time to relax. He was anxious. He knew there was no road map for this session. That was not how interrogation worked. Conversations were improvisational. You never knew when an offhand remark might give you the answer you needed, when a poorly worded question might instantly shut down a suspect, or how an important insight might leap from a slip of the tongue. Chris and Pete would be in an adjacent room watching and listening. Dave would be able to consult with them at intervals, but what happened in the moment would be up to him.

It wouldn’t just be an interview—it would be a performance.

A PEBBLE IN THE SHOE

The taking of Sheila and Kate Lyon had cried out for justice over decades. It wasn’t just a mystery; it was a regional trauma. The crimes that most terrorize us are those that occur where we feel happy and safe. This one struck to the hearth, a shock to anyone who has ever loved a child or remembered being one.

For the Montgomery County Police Department, it was also an embarrassment, a blot both professional and personal. Professional because it was unsolved, the most notorious such case on its books in a half century. Personal because one of the girls’ two brothers, Jay, had grown up and joined the force. With its fierce fraternal tradition, that had made it a family tragedy.

It was a pebble in the department’s shoe. Generations of county detectives had come and gone, and many had taken a crack at it. Periodically, a new cold case team would start over, combing through the many boxes of yellowing evidence, hoping to find something missed. Ed Golian, now retired, had worked the case off and on for his entire career, from before he had even earned his badge. He had been in the academy when the sisters disappeared. His entire cadet class was pressed into the search, striding an arm’s length apart in long rows through wet spring fields, beneath the staccato thrum of a helicopter that swept a moving spotlight. Golian and the others had manned long tables late into the night sorting the flood of tips and sightings. They were also asked to assemble a list of every known sex offender in the area, compiling, they were told, something called a “database.” At the time, Golian wasn’t sure what that meant.

Fruitless suspicion had fallen at first on the girls’ father, John Lyon, for no reason other than statistics—most crimes against children were committed by family members—and sheer desperation. But the Lyon family was a happy one. Their photos—four sunny children posing on the beach or dressed in their Sunday best in the front yard or peering out happily from the back window of the family station wagon—depicted a contemporary suburban ideal. Sheila stood out in all the pictures, with her glasses and bright blond pigtails, from early childhood to the picture taken of her dressed all in white, her legs grown long and lean, posing before a shrub on the day of her First Communion. Kate looked like more of a tomboy, with even brighter blond hair, cut shorter than her sister’s, and a spray of freckles across the bridge of her nose. The drawings and cards and notes the girls left behind in their bedrooms were heartbreakingly innocent and joyful. John and Mary were loving parents, guilty of nothing more than letting their girls walk unsupervised down the street to the mall to buy slices of pizza. They were bereft.

That much was plain to anyone who saw them those first days, as I did, working the story as a new reporter for the Baltimore News-American. Knowing that any attention might help, the couple opened up their small white stucco house on the corner to everyone, family, friends, and even reporters. They passed out cans of beer and cups of coffee. Mary was unusually composed—she was on a diet of tranquilizers—but her face was red and drawn. John was a study in well-contained panic, a man with a wry sense of humor about himself, someone cool, trapped in a circumstance for which there was no cool way to behave. I remember sitting with him in the enclosed side porch of his house as he vacantly strummed a guitar and tried patiently to answer my useless questions.

They were a handsome pair, John rugged and hip, Mary pretty, small, and slender, with short dark hair. Both were in their thirties. They had met at Xavier University in Cincinnati, when John had been a full-time student and Mary a part-time one. He was from Chicago, and she was from nearby Erlanger, Kentucky. They married in Erlanger and had their first child, Jay, shortly before moving to Chicago, where they lived with John’s parents while he completed his degree by taking night classes at Columbia College. He worked days at Sears in the Loop. After graduation he’d gotten a job at a radio station in Ohio, where Sheila was born, and then one in Streator, Illinois, where Kate was born, and then a bigger job, in Peoria—“The big city!” Mary joked—where John worked in both radio and TV. He appeared on a daytime kids’ show, introducing movies with his guitar and banjo. He and Mary sometimes performed with a folk band in those years, during which she gave birth to their youngest, Joe. The job at WMAL was a big step up. It was the most popular radio station in Washington, DC, and by now John was a seasoned on-air personality. He had long, dark hair beginning to show strands of gray and a droopy mustache and spoke with the deep, melodious tones of a radio pro. He worked as a fill-in disc jockey and sometimes read the news and still performed with a band, called Gross National Product, that played gigs in the area. John and Mary were charming and witty and fun, accustomed to the spotlight, which helped explain their remarkable poise at the center of this awful one. Tragedy felt like a complete stranger in their home, a reminder of the most banal of truths: you can do absolutely everything right and still be rewarded with unconscionable cruelty.

In those first days there was disbelief and hope. Maybe it was all a snafu and the girls would turn up. John went on the air at WMAL the day after they vanished, speaking calmly and modestly.

“I’m sure we’re going to feel stupid about this,” he said. “They probably told us they were going to a sleepover and we forgot. If anybody knows where they are, please send them home.”

Kensington, where the Lyons lived, was north of Washington, well outside the Capital Beltway, adjacent to the booming edge city of Silver Spring. It had been farmland until the end of the nineteenth century, when an Anglophile DC developer bought lots and replicated a Victorian village, which would lend a quaint character to the suburban homes that sprang up around it. First popular as an escape from the swampy district summers, it was overtaken by the suburban explosion that followed World War II. By the 1970s Kensington was a bedroom community for Washington commuters, most of them government workers, nearly all of them white, and still something of an escape, not so much from DC’s climate as from its crowded, increasingly black, restive, and troubled core. Together, Kensington and the larger, adjacent suburb of Wheaton were home to fifty thousand people and distinctly middle to upper class. They were like thousands of other suburbs ringing American cities, havens for whites fleeing the black urban migration, seeking comfort in racial and demographic homogeneity. Largely new, green, clean, and prosperous, Kensington was considered an idyllic place to raise a family.

Before the age of continuous cable TV news and the Internet, children’s disappearances were primarily local tragedies and did not automatically attract strong news coverage. In big cities like Washington and Baltimore, newspapers were the primary medium, and they had come a long way from their sensationalist roots. Journalism was now a white-collar profession. Reporters for the big papers saw their work as public service—the Washington Post was fresh off the triumph of Water-gate. In Baltimore, the most respected paper was the Baltimore Sun, a dignified modern daily that headlined those stories its editors deemed important—an amendment to a piece of tax legislation in Annapolis would get better play than a lurid local crime. With its news bureaus all over the country and the world, the Sun was in the business of educating and informing readers. My paper, the Baltimore News-American, on the other hand, was a throwback. It was part of the Hearst chain. It had nothing like its competitor’s resources (or talent), took itself less seriously, and, for better or worse, still showed its yellow roots. Its priority was still whatever sells. In keeping with that approach, my job was to show up in the newsroom at four in the morning and phone every police barracks in the state, asking whether anything interesting had happened overnight. This was a mind-numbing task and usually produced nothing, but when, on the morning of March 26, 1975, the desk officer in Wheaton told me about the missing children, I drove directly to the scene. Ours was an afternoon paper, so if the story was interesting enough—which this clearly was—and I moved fast enough, it was possible to slap a story on the front page later that day. It was sure to attract attention. Millions of families in the region lived in neighborhoods just like Kensington, shooing their kids out the door in the morning and catching up with them at mealtimes, unconcerned about where they went, because every house on every block was inhabited by families just like their own. A story like this struck at suburbia’s idea of itself.

My first story ran on a Thursday, two days after the girls vanished, under the headline, “100 Searching Woods for 2 Missing Girls.” It had photos of Sheila, in pigtails and glasses, and Kate, with her hair cut in a cute bob. By the next morning, Good Friday, the FBI and the Washington, DC, police department had joined the effort, and the story led the local news in the Washington Post: “Police Press Search for Missing Girls.” As days passed with no good news, the tale turned grimmer. No one wanted to imagine the girls’ fate. In my newspaper the story was still on the front page at the end of the week: “Hope Fades in Search for Girls.” Every TV and radio news broadcast led with it, sparking a huge public response. More than three hundred people phoned the police in the first three days alone to say they had seen the girls, and all these tips had to be checked out. The family heard from everyone they’d ever known.

“We’ve had hundreds of phone calls from well-wishers,” John told me, two days after the girls had disappeared. “Most are from perfect strangers. They want to know what they can do to help. I wish I knew what to tell them.”

Every stand of woods or weeds was searched. Storm sewers were explored, as was every vacant house for miles. The residents of a nearby nursing home were interviewed, one by one. Scuba divers groped through mud at the bottoms of ponds. John stood by one chilly afternoon, shivering, his hands thrust deep into the pockets of his white Levi’s, as divers disappeared into a small lake on the grounds of the nearby Kensington Nursing Home. He waited awkwardly . . . for what? How did one both want and desperately not want to find something? Nothing was found. Nothing came of anything the police did, despite occasional moments of excitement. Thirteen days after the girls vanished, on April 7—long after hopes of finding them alive had faded—there was a call from an IBM employee who, on his way to work in Manassas, Virginia, had stopped at a red light behind a Ford station wagon. He had been startled to see in its rear the head of a blond child, bound and gagged. He jotted down the license-plate number, all but the last digit, which he couldn’t see because the plate was bent. The driver of the station wagon, apparently noticing the other driver eyeing him from behind, had suddenly accelerated through the red light and sped off through the intersection. In that pre-cell-phone era, the IBM man phoned in the tip when he got to his office and later that day was questioned and polygraphed. He wasn’t sure whether the plate had been from Maryland or North Carolina—the new bicentennial plates of these states were similar—but his story was sound. Lists were compiled of all cars with plates that matched the description, from both states, and efforts were made to find them. Nothing came of it.

This nightmare unfolded in the context of larger national unease. Ground was shifting under enduring institutions of American life, and the promise that had propelled the country so dynamically through the 1950s and ’60s had soured. Jobs were scarce, and paychecks didn’t go as far—a phenomenon dubbed “stagflation.” Americans had stopped buying stocks—they were no longer betting on the future. The Vietnam War was spiraling to humiliating defeat after dominating headlines for more than a decade. President Nixon had resigned in a scandal, and each week another top member of his administration went to jail. There were revelations of domestic spying and of troubling American involvement in foreign coups and assassination plots, both ludicrous and disturbing. Government suddenly appeared not just untrustworthy but inept. Violent crime in nearby Washington had nearly doubled in the previous five years. The Summer of Love had degenerated into drug abuse and violent radicalism. Strange groups were setting off bombs and abducting people—tracking dogs used in the hunt for the Lyon sisters had been used a year earlier to look for kidnapped heiress Patty Hearst. On TV, the most popular character was Archie Bunker, a blue-collar American male railing hilariously against the collapse of his preferred social order.

The day Sheila and Kate went missing was an early taste of spring. There had been two snowfalls that March, but the weather before Easter week had turned warm and muggy. That Tuesday morning John worked the midnight-to-six shift, after which he drove home and went to bed. He woke up at one in the afternoon to an empty house. Off school for spring break, Sheila and Kate had gone to the mall. They had left with about two dollars between them, complaining that the cost of a pizza slice at the Orange Bowl had recently gone up five cents. There had been a time when Sheila did not want her younger sister with her, but in recent months Mary felt they had begun to play happily together again. Mary had gone bowling, and the Lyon boys were off with friends in the neighborhood. Mary and Joe were home soon after John got up, and when he went back to bed for a mid-afternoon nap, she took a rake to the matted leaves in the backyard that had been buried in snow just weeks before. At dusk she began missing the girls. She assumed they were with friends and having fun. They were usually prompt at dinnertime, and ordinarily Sheila would call if they were delayed. But she had not called. John and Mary ate dinner with their boys, two empty chairs at the table, Mary now annoyed. With still no word after they’d finished, they started calling all the girls’ friends. Nothing. They drove around the neighborhood with a mounting sense of alarm. Then they called the police.

Many teenagers and even children go absent from their homes—there had been eighteen hundred reported cases in Montgomery County alone in the previous year, but most involved slightly older children, and in nearly every case they were quickly found. That this report was different was rapidly becoming apparent, and when the girls remained missing through that night it became a crisis. According to John and Mary, this was utterly out of character. Both girls were obedient. They were honor roll students. Kate was the outgoing, athletic, silly one. She was a fifth grader at Oakland Terrace Elementary School and had a poster of pop singers Loggins and Messina in her bedroom. Her mother had just given her permission to get her ears pierced. Sheila was the dreamy one, quieter and more of a homebody. The poster in her room was of the romantic folk balladeer John Denver. She had started to help her mother cook, had begun wearing eye shadow, and had recently taken her first babysitting jobs. A seventh grader at Newport Junior High, she was hoping to make the school’s cheerleading squad. Neither girl had taken money from her piggy bank or extra clothing, telltale signs of a runaway.

“No,” John told me, with crisp certainty. “They did not run away. I really wish there was a reason for believing they did.”

As a green, twenty-three-year-old reporter, I tried to see the Lyon case as a story, my first chance to write front-page news. The people I wrote about were subjects, and tragedy was a thing that happened to others. But the Lyons were people I liked, even admired. I could not witness their pain dispassionately.

Of the thousands of missing children cases reported each year, those involving children taken by a stranger number only one one-hundredth of one percent—on average about one hundred cases a year in the United States, a number that has changed little for as long as such statistics have been kept. Nearly all missing children are found quickly. For two to be taken at once and to disappear completely is a thing so rare that it’s almost true to say it never happens—the numbers are so low they cannot be meaningfully framed as a percentage of overall kidnappings. Needless to say, very few people are ever touched personally by such crimes, but today’s omnipresent tabloid-style journalism and social media so magnify every occurrence that people are unduly afraid. American children in the twenty-first century lead far more sheltered, supervised lives than children of earlier times. Only thirteen percent still walk to school. Parents who leave a child untended for even a short time may find themselves reported to the police. While today we can all too readily imagine the disappearance of a child, in 1975 it was shocking—and all the more so in this case because it was two children. Imagining how or why was difficult. The problem of controlling two alarmed children at those ages suggested more than one kidnapper, which raised the question, why? What would motivate two people or a group? A sex-trafficking ring? A circle of pedophiles? Just speculating about it conjured scenarios that made you ashamed to be human.

A few weeks after the girls vanished, as if to underscore the potential for cruelty, opportunists began to surface. There were psychics who claimed to have “seen” where the girls were. There were extortionists. One man called the Lyon home and said he would return Sheila and Kate for a payment of $10,000. John drove to the appointed location, a bus station in Annapolis, with a briefcase—in it was just $101, enough to make the crime a felony. He was told to wait there for a pay phone to ring. It did. The caller, a man, instructed him to walk across the street to the county courthouse and put the briefcase in a trash can inside the first-floor men’s room. The man said he would then drop the girls off in front of the building. With police watching from a distance, John did as instructed. He then stood expectantly for hours before the courthouse, hopefully eyeing every car that passed. He and his police escort only gave up when the courthouse shut down for the day. They retrieved the briefcase and drove home. John was desperately disappointed and furious. The same man phoned the next morning and said that he hadn’t followed through because there were too many cops around. John pointed out the stupidity of selecting a courthouse if he was trying to avoid cops. He told the man not to call back unless he could put one of the girls on the phone. They did not hear from him again.

There were other, even less sophisticated extortion attempts. One caller told John and Mary to drop $6,000 in an air vent outside the Kensington Volunteer Fire Department, and another instructed them to stand with exactly $1,050 outside the Orange Bowl at Wheaton Plaza. Two months after the girls disappeared, a tip from a Dutch psychic who claimed to have helped solve the Boston Strangler case sent 150 police and National Guardsmen on a daylong search of nearby Rock Creek Park. They found nothing. John and Mary gradually closed themselves off from such contacts, stopped giving interviews, and worked to avoid being consumed with bitterness. The loss of a child is a shattering experience for any family. For the Lyons—John, Mary, Jay, and Joe—it would be a hard task to salvage what was left.

To me, the story was sad and beyond understanding. Like everyone else, I waited for the police to find something and explain the mystery. In time, the story moved off the front page and then out of the news completely, overtaken by fresh outrages. As the decades passed I wrote thousands more stories, big ones and small ones. I raised five children of my own. I experienced tragedy and loss in my own life. I became a grandfather—of two little blond-haired girls, as a matter of fact. Few stories haunted me as this one did.

When he was nearing retirement, Ed Golian, who had joined the search effort as a cadet thirty years earlier, was assigned to the department’s cold case team in 2011, typically a last stop before hanging up the badge. As had other detectives before him, he reopened the Lyon files, ending his career with the same case that started it.

Today police have new tools for old crimes. DNA testing offers seemingly magic solutions to decades-old mysteries as long as physical evidence has been preserved. With no bodies and no crime scene, there would be no such magic for this one. Computers held promise. No longer a novelty, they cast a far wider net than even the massive application of manpower applied in those first weeks to finding Sheila and Kate. The machines made it inestimably easier for Ed to complete the old sex-offender lists, to compile time lines, and to cross-check names and incidents for intersections with Wheaton Plaza in 1975. The old list of car registrations that met the IBM man’s description was broadened and rechecked. More than three decades later Ed found, of course, that most of these cars had vanished to junkyards. Many owners were no longer alive. Still, all the leads were tracked down, yielding nothing.

This is what cold case teams do. They embrace the tedium. They are the turners of last stones, laboring in a landscape beyond hope. The task is Sisyphean. By its nature, investigation continually churns up new leads, prolonging both the work and the frustration. The Lyon file filled thirty boxes. Golian worked with four other detectives: Chris Homrock, who at forty-one had twenty years of experience in the department; and three who, like Ed, were nearing retirement, Joe Mudano, Bobby Nichols, and Kenny Penrod.

Instead of adding more to the files, the squad decided to weed them. The detectives set out to identify every plausible suspect and reinvestigate enough to either eliminate him or keep him. That work took two years. All the detectives were working on other cases at the same time—Chris was running the department’s robbery section, and Kenny led the homicide section—but the puzzle was such a noteworthy challenge that it was always on their minds. The suspects included a fellow named Fred Coffey in South Carolina, whom Kenny favored; another suspicious predator, Arthur Goode; and the infamous sexual sadist and serial killer James Mitchell “Mike” DeBardeleben, all of whom had stories with potential links to the Lyon girls. None could be completely eliminated.

But one jumped out—Ray Mileski, who had died in prison in 2005.

MILESKI

By 2013, Chris Homrock was the only one left in the Lyon squad. One by one, Ed Golian, Joe Mudano, Bobby Nichols, and Kenny Penrod had retired. Chris had become obsessed with the case. He talked about it constantly with his wife, Amy, also a police officer, and she encouraged him. If anyone could crack the mystery, she thought, Chris could. He was a natural. He always seemed to know what question to ask next; he could think on his feet better than anyone else she had ever met. No matter how long and hard he worked, no matter how elusive the answers, Amy would have been the last to tell him to stop. Just a few years younger than Sheila and Kate, and having grown up in nearby Potomac, Maryland, she remembered their disappearance well. Her parents referred to the case as a “permanent loss of innocence.” Now she and Chris had two daughters who were roughly the same ages Sheila and Kate had been. They could only imagine John and Mary’s suffering. So Amy was all in, even if for Chris it meant working long hours, losing sleep, and not eating right. Not that she didn’t try to tamp down his intensity now and then, reminding him that the girls were not tied to a tree somewhere awaiting his rescue. His job was to figure out what had happened, to find who had taken them, perhaps to bring the story of their terrible last days—and maybe their remains—home at last to the Lyon family.

But by the early summer of that year, Chris was ready to give up. He felt weighed down with both responsibility and futility. Despite his years of effort, the trail, if anything, had grown colder. Mileski was the one thing that had kept him going.

A petty criminal, killer, and audacious pedophile, Mileski had inserted himself into the investigation. In 1975, he had called the Montgomery County police twice: first with a suggestion—they should offer immunity to the person who kidnapped the girls if he returned them—and then, two weeks after the girls vanished, with a tip. He said he had seen the widely publicized suspect, the gray-haired man with a tape recorder, weeks before the Lyon sisters disappeared, trying to lure children into his car at another mall. He gave the police a detailed account. Then, two years later, the same Ray Mileski shot and killed his wife and one of his sons. In prison for those crimes, he had talked a lot about the Lyon sisters, telling other inmates that he knew where the girls were buried. Police investigated these claims in 1982, partially excavating Mileski’s old backyard and basement. They found nothing.

That had stalled active work on Mileski, but when the squad took another hard look at him in 2011, interest in him deepened. Reviewing old witness interviews from after he was arrested for murder, the detectives learned that one possible motive for the killings had been to prevent his wife and son from revealing his connection to the Lyon case. On his bedside table, the night of the murders, police had found a slip of paper with John Lyon’s phone number on it.

And the more Chris looked, the more he found. Witness after witness said Mileski was known to pick up young boys and girls for sex. One said he had done this once at Wheaton Plaza. Another said he had seen two little blond girls in Mileski’s basement. One woman said that Mileski had raped her on two different occasions when she was a teenager and that he had held sex parties at his suburban home. Men admitted, under hard questioning, that as boys they had been intimidated by Mileski into engaging in sex acts. Chris learned that Mileski had been part of a group of men who engaged in such activities, sometimes gathering at parties to share young victims.

It all fit. Mileski had been a pedophile associated with other pedophiles who swapped child pornography and groomed and shared victims. In time, Chris came to believe in his bones that this was his man, but the case was all circumstantial. He had talked the young couple who owned Mileski’s old house into letting him rip out the carpeting in their basement to inspect the concrete floor. He found nothing (and paid to recarpet the floor). At one point Chris learned that Mileski had purchased undeveloped land in Lancaster County, Virginia. Chris then spent weeks there, living in a motel, supervising a dig on the property in a futile search for remains. He would come home and tell Amy how close he felt, almost as if he could hear the Lyon girls calling to him from their graves. He found nothing. Now he wanted to go back to the old Mileski basement and tear through the concrete, but no judge was going to okay that without a strong justification. The gut feelings of a veteran detective didn’t count.

Chris had run out of moves. Continually paging through the files, he felt as if he were wearing deeper ruts in a well-worn road. No lead had gone unpursued, no witness unquestioned. It made him angry and stung his pride. He considered himself a pro, and he had struck out. He was at his desk one evening, early that summer, reviewing documents so familiar he could almost recite their contents, when it struck him. He was finished. He had done everything he could do. He was not a man to give up, but he had reached a dead end. The feeling surprised him. He walked to the lavatory and splashed water on his face. It was not so much a decision as a recognition. There was nothing left for him to do. It was deeply disappointing but also a relief. He would put the burden down. If Sheila and Kate were still alive, they would both be middle-aged, a good bit older than John and Mary had been in 1975. Like all those before him, Chris had failed. At least he could tell the Lyons, in good conscience, that he had done everything possible.

But when he returned to his desk, staring at him from a stack of old familiar files was one he could not remember having seen—the six-page transcript of Lloyd Welch’s April 1, 1975, statement. He was first astonished that he had somehow missed it. How could that be? And how had it come to sit on top of the papers on his desk? Could someone else have put it there? No one was working nearby. It had clearly come from his own collection. He read it for the first time, somewhat amazed, and felt a jolt when he reached the end. This witness had told the detectives that the man who led the girls from the mall “walked with a little limp.”

That had to be Mileski! During a lifetime of run-ins with the law, Mileski had once been caught in a home burglary and had been shot in the leg by police. Afterward, he limped.

Chris could not believe he had never seen this. Here was someone, this Lloyd Welch, who may have actually seen Mileski in the mall with the girls! If this was true—an eyewitness!—it might be the break he needed.

He showed the old statement to two robbery detectives who worked for him, Dave Davis and Kari Widup.

As they read it, Chris could hardly contain his excitement.

“See the part about him walking with a limp?” he said. “He’s describing Ray Mileski!”

Both detectives agreed that it was intriguing, but neither knew enough about the case to fully share Chris’s excitement. Dave, the seasoned interrogator, noted that the witness’s recall in this old statement seemed suspiciously detailed. In his experience, it went well beyond what any normal teenager would have to offer. Most would never look twice at two little girls. Still, he could see the importance of a potential living witness.

“He would be in his fifties now,” said Dave, which meant there was a good chance he was still around.

Welch’s old flunked polygraph didn’t mean much to Dave; he put little stock in the device. He told Chris he thought it was a good find. Running to a meeting, Chris asked him to do some Internet sleuthing to see whether he could find the man.

A quick scan of state criminal records disclosed Welch’s repeated run-ins with Montgomery County. There was a photo attached to a 1977 arrest, showing Welch staring sullenly into the camera. He looked older than his years, kicked around, hardened, a man with scars on his broad face and wide, crooked nose. His thick brown hair was parted in the middle, held down by a dirty, rainbow-colored headband.

Dave confirmed that Welch was still living by calling family members, some of whom were named in the police records. He called an old number in Tennessee, and Welch’s elderly stepmother, Edna, answered. Dave identified himself. “We’re doing an investigation,” he said. “It’s from a very long time ago.” Edna sounded confused and said she could not hear him well—he suspected that she was trying to get rid of him. She told him to call her son Roy, Lloyd’s younger half brother.

“I know he’s incarcerated,” said Roy, with what sounded like a chuckle—wouldn’t a cop know this already? “He’s in Delaware for something to do with little kids.”

Those words rang loud. Roy didn’t offer any more, but Dave now cast a wider digital net. Using a national police database, he found all of Welch’s arrests and his disturbing history of sex crimes against children. He had worked for a traveling carnival, which explained the wide-ranging geography of his criminal past. The most recent photo, a prison shot, showed the same face grown older and thicker, sneering down at the lens. Lloyd had lost his hair, his youth, and his freedom. He had a gray mustache and goatee.

When Chris didn’t pick up his phone, Dave texted him: “We’ve located him. Issues with sexual stuff with kids. Currently incarcerated.”