Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Serie: 16Lives

- Sprache: Englisch

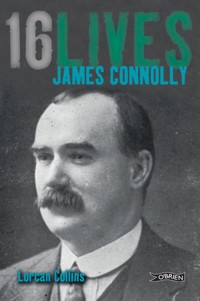

James Connolly (1868-1916) became a leading Irish socialist and revolutionary, and was one of the leaders of Ireland's rebellion in 1916. As a youth he had served in the British army in Ireland and, seeing how they treated the local population, became hugely disillusioned with the British Army. He became involved in socialism in Scotland and was the driving force behind the creation of Ireland's trade union movement. He was Commandant of the Dublin Brigade in the Easter Rising and, too injured to stand before the firing squad, was executed tied to a chair. Written in an entertaining, educational and assessible style, this biography is an accurate and well-researched portrayal of the man behind the uprising. Including the latest archival evidence, James Connolly is part of the Sixteen Lives series which looks at the events, lives and deeds of the sixteen men executed for their role in Ireland's Easter 1916 Rising.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 431

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

16LIVESJAMES CONNOLLY

The 16LIVESSeries

JAMES CONNOLLYLorcan Collins

MICHAEL MALLINBrian Hughes

JOSEPH PLUNKETTHonor O Brolchain

ROGER CASEMENTAngus Mitchell

THOMAS CLARKELaura Walsh

EDWARD DALYHelen Litton

SEÁN HEUSTONJohn Gibney

SEÁN MACDIARMADABrian Feeney

ÉAMONN CEANNTMary Gallagher

JOHN MACBRIDEWilliam Henry

WILLIE PEARSERoisín Ní Ghairbhí

THOMAS MACDONAGHT Ryle Dwyer

THOMAS KENTMeda Ryan

CON COLBERTJohn O’Callaghan

MICHAEL O’HANRAHANConor Kostick

PATRICK PEARSERuán O’Donnell

DEDICATION

For Trish

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My wife Trish Darcy, to whom this unworthy work is dedicated, for her endurance, commitment, strength, love and unwavering support. My loving children Fionn and Lily May whose first words were James Connolly. My mother Treasa and my father Dermot and their strong sense of Irish culture and heritage. Michael O’Brien for having the vision and bravery to take on this project with such enthusiasm. Mary Webb for her enduring support and guidance. My brilliant series co-editor Dr Ruán O’Donnell. Susan Houlden for her editorial skills. Emma, Ivan, Ide, Kunak, Carol, Helen and everyone at the O’Brien Press. Anne-Marie Ryan for her kindness and everyone at Kilmainham Goal. Conor Kostick for guidance and suggestions. John Donoghue, James Donoghue, Alan Martin, John Francis, Kenny and all at the International Bar for their constant support. John Gibney. Jim Connolly Heron. John Connolly. Seamus Connolly. Peter Reid. In Troy, New York: MaryEllen Quinn, Samantha Quinn. Jim P Coleman in Albany. Declan Mills. Joe Connell. Everyone at Dublin Tourism. Orla Collins and Mark Childerson, Aoife, Oisín and Ferdia. Diarmuid Collins and Eibhlis Connaughton. Carmel Darcy and Pat Darcy. All the Collins clan, the Farrell family and all the Darcy family. Ciara Gallagher. Rhonda Donagahy, SIPTU. Gary Quinn. Daithí Turner. Prof Andrew Hazucha. Prof Shawn O’Hare, Prof John Wells. Brian Donnelly, Elizabeth McEvoy, Mick Flood and Lorcan Farrell at the National Archives. Keith Murphy at the National Photographic Archives. Gerry Kavanagh, Patrick Sweeney, Michael McHugh, James Harte, Colette O’Daly at the National Library of Ireland. Lisa Dolan, Commandant Victor Laing, Noelle Grothier, Capt Stephen MacEoin, Pte Adrian Short and Hugh Beckett at the Bureau of Military Archives, Cathal Brugha Barracks. Rev Joseph Mallin, Hong Kong. All at Dublin Castle. Honor O Brolchain. All at the GPO. Brian Crowley and everyone at the Pearse Museum. Carol Murphy, SIPTU. Tom Stokes and Frank Allen. Paul Turnell. Shane MacThomáis at Glasnevin Museum. David Kilmartin and the 1916–21 Club. Caoilfhionn Ní Bheachain. Terry O’Donoghue. Caoimhe Nic Dháibhéid. Cliff Housley and the WFR Museum, Sherwood Foresters Archives. Gearóid Breathnach. Coilín O’Dufaigh. Ruarí O’Duinn. Nicky Furlong. Ciaran Wyse at Cork County Library. Dan Burt and Deb Felder. Mick Green, Kevin Lee and Joseph Dowse in Carnew, Wicklow. The 16 Lives authors – a great collective. Thank you also to all my friends and colleagues for their patience and support and finally thanks to all the Dubliners who pass me by every day with a cheery word or two.

16LIVESTimeline

1845–51. The Great Hunger in Ireland. One million people die and over the next decades millions more emigrate.

1858, March 17. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, are formed with the express intention of overthrowing British rule in Ireland by whatever means necessary.

1867, February and March. Fenian Uprising.

1870, May. Home Rule movement, founded by Isaac Butt, who had previously campaigned for amnesty for Fenian prisoners

1879–81. The Land War. Violent agrarian agitation against English landlords.

1884, November 1. The Gaelic Athletic Association founded – immediately infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

1893, July 31. Gaelic League founded by Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill. The Gaelic Revival, a period of Irish Nationalism, pride in the language, history, culture and sport.

1900, September.Cumann na nGaedheal (Irish Council) founded by Arthur Griffith.

1905–07.Cumann na nGaedheal, the Dungannon Clubs and the National Council are amalgamated to form Sinn Féin (We Ourselves).

1909, August. Countess Markievicz and Bulmer Hobson organise nationalist youths into Na Fianna Éireann (Warriors of Ireland) a kind of boy scout brigade.

1912, April. Asquith introduces the Third Home Rule Bill to the British Parliament. Passed by the Commons and rejected by the Lords, the Bill would have to become law due to the Parliament Act. Home Rule expected to be introduced for Ireland by autumn 1914.

1913, January. Sir Edward Carson and James Craig set up Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) with the intention of defending Ulster against Home Rule.

1913. Jim Larkin, founder of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) calls for a workers’ strike for better pay and conditions.

1913, August 31. Jim Larkin speaks at a banned rally on Sackville Street; Bloody Sunday.

1913, November 23. James Connolly, Jack White and Jim Larkin establish the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) in order to protect strikers.

1913, November 25. The Irish Volunteers founded in Dublin to ‘secure the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland’.

1914, March 20. Resignations of British officers force British government not to use British army to enforce Home Rule, an event known as the ‘Curragh Mutiny’.

1914, April 2. In Dublin, Agnes O’Farrelly, Mary MacSwiney, Countess Markievicz and others establish Cumann na mBan as a women’s volunteer force dedicated to establishing Irish freedom and assisting the Irish Volunteers.

1914, April 24. A shipment of 35,000 rifles and five million rounds of ammunition is landed at Larne for the UVF.

1914, July 26. Irish Volunteers unload a shipment of 900 rifles and 45,000 rounds of ammunition shipped from Germany aboard Erskine Childers’ yacht, the Asgard. British troops fire on crowd on Bachelors Walk, Dublin. Three citizens are killed.

1914, August 4. Britain declares war on Germany. Home Rule for Ireland shelved for the duration of the First World War.

1914, September 9. Meeting held at Gaelic League headquarters between IRB and other extreme republicans. Initial decision made to stage an uprising while Britain is at war.

1914, September. 170,000 leave the Volunteers and form the National Volunteers or Redmondites. Only 11,000 remain as the Irish Volunteers under Eóin MacNeill.

1915, May–September. Military Council of the IRB is formed.

1915, August 1. Pearse gives fiery oration at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa.

1916, January 19–22. James Connolly joined the IRB Military Council, thus ensuring that the ICA shall be involved in the Rising. Rising date confirmed for Easter.

1916, April 20, 4.15pm.The Aud arrives at Tralee Bay, laden with 20,000 German rifles for the Rising. Captain Karl Spindler waits in vain for a signal from shore.

1916, April 21, 2.15am. Roger Casement and his two companions go ashore from U-19 and land on Banna Strand. Casement is arrested at McKenna’s Fort.

6.30pm.The Aud is captured by the British navy and forced to sail towards Cork Harbour.

22 April, 9.30am.The Aud is scuttled by her captain off Daunt’s Rock.

10pm. Eóin MacNeill as chief-of-staff of the Irish Volunteers issues the countermanding order in Dublin to try to stop the Rising.

1916, April 23, 9am, Easter Sunday. The Military Council meets to discuss the situation, considering MacNeill has placed an advertisement in a Sunday newspaper halting all Volunteer operations. The Rising is put on hold for twenty-four hours. Hundreds of copies of The Proclamation of the Republic are printed in Liberty Hall.

1916, April 24, 12 noon, Easter Monday. The Rising begins in Dublin.

16LIVES- Series Introduction

This book is part of a series called 16 LIVES, conceived with the objective of recording for posterity the lives of the sixteen men who were executed after the 1916 Easter Rising. Who were these people and what drove them to commit themselves to violent revolution?

The rank and file as well as the leadership were all from diverse backgrounds. Some were privileged and some had no material wealth. Some were highly educated writers, poets or teachers and others had little formal schooling. Their common desire, to set Ireland on the road to national freedom, united them under the one banner of the army of the Irish Republic. They occupied key buildings in Dublin and around Ireland for one week before they were forced to surrender. The leaders were singled out for harsh treatment and all sixteen men were executed for their role in the Rising.

Meticulously researched yet written in an accessible fashion, the 16 LIVES biographies can be read as individual volumes but together they make a highly collectible series.

Lorcan Collins & Dr Ruán O’Donnell,

16 Lives Series Editors

CONTENTS

Introduction

If you remove the English army to-morrow and hoist the green flag over Dublin Castle, unless you set about the organisation of the Socialist Republic your efforts would be in vain.1

James Connolly (1868−1916) was born in the slums of Edinburgh, where he received only a basic primary education and seemed, like many of his peers, destined to struggle through life, working for low wages in grinding poverty. He joined the British army at a very young age and was posted to Ireland. Being of Irish descent, his sympathy was with the poor and downtrodden of Dublin and the rest of the country. He saw no difference between the lot of the tenant farmer under the yoke of a landlord and that of an Edinburgh factory worker under a capitalist. A strong family man, he dedicated his whole life to attempting to revolutionise the economic system so that his children and future generations would have hope, security and a better life.

His socialist ideas were rejected, often by the very people who he was trying to emancipate. Having founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party in Dublin, it split after a few years and Connolly was forced to emigrate to the United States of America. He was active with a number of socialist organisations, most notably the Industrial Workers of the World (Wobblies) and the Socialist Party of America. However, he returned to Ireland where he spent the last six years of his life fighting against British imperialism and Irish capitalism.

James Connolly linked Irish nationalism with socialism. He saw no reason for merely changing the colour of the flag which flew over Dublin’s government buildings; rather he hoped to bring about social change alongside an Irish republic. His articles and books, written in an accessible and straight-forward style, are still read and relevant today. He never wavered on the road to revolution and, as head of the Irish Citizen Army, he joined forces with the Irish Republican Brotherhood and led an insurrection against British rule in Ireland.

Connolly’s last moments were spent in a chair in the stone-breakers’ yard in Kilmainham Gaol, where, in the early hours of 12 May 1916, a British army firing squad took his life. However, his ideals, his words, his deeds and his dreams live on and, perhaps, one day his wishes for a better world and a better future will be fulfilled.

But that day will come only when the kings and kaisers, queens and czars, financiers and capitalists who now oppress humanity will be hurled from their place and power, and the emancipated workers of the earth, no longer the blind instruments of rich men’s greed, will found a new society, a new civilisation, whose corner stone will be labour, whose inspiring principle will be justice, whose limits humanity alone can bound.2

Notes

1Shan Van Vocht, January 1897.

2Workers’ Republic, 3 September 1898.

Chapter One • • • • • •

1868–1889

The Early Years

The cause of labour is the cause of Ireland, the cause of Ireland is the cause of labour. They cannot be dissevered.1

The Great Hunger of the 1840s was a major turning point in the fortunes of Ireland and the Irish. Under direct rule from the British Parliament in Westminster, more than one million people perished from starvation and diseases related to malnutrition, and one million people were forced to emigrate. The social structure of rural Ireland underwent a tremendous upheaval.

During the nineteenth century a very large section of Ireland’s citizens existed in some of the poorest and most deprived conditions in Europe. ‘The Irish peasant,’ wrote James Connolly, ‘reduced from the position of a free clansman owning his tribeland and controlling its administration in common with his fellows, was a mere tenant-at-will subject to eviction, dishonour and outrage at the hands of an irresponsible private proprietor. Politically he was non-existent, legally he held no rights, intellectually he sank under the weight of his social abasement, and surrendered to the downward drag of his poverty. He had been conquered, and he suffered all the terrible consequences of defeat at the hands of a ruling class and nation who have always acted upon the old Roman maxim of “Woe to the vanquished.”’2

At that time some argued that British rule in Ireland was benevolent, but little or nothing was done to help the poor and starving. In fact, the great shame is that the British government allowed goods and produce to be exported from Ireland during the Great Hunger, hardly a sign of altruism. Emigration, already a common enough problem, speeded up phenomenally. Now known as the Irish Diaspora, the mass exodus saw the population of Ireland cut down to half its original number within a couple of decades. Those who could afford it would pay the fare to Australia, New Zealand, Canada and, of course, America, where those of Irish descent now constitute somewhere in the region of forty million. The logical destinations for the poorest Irish emigrants included England, Wales and Scotland. James Connolly’s parents were refugees from the Great Hunger who settled in Scotland.

Over the years, historians have been preoccupied with a desire to prove that James Connolly was born in Ireland. In 1916 the Weekly Irish Times published a very detailed Rebellion Handbook. One section contained a ‘who’s who’ of the Easter Rising. The entry for James Connolly states that he was ‘a Monaghan man’.3 In 1924, Desmond Ryan, the respected historian and author, wrote of how, in 1880, the Connolly family was forced by poverty to move from their native Monaghan to Scotland. In 1941 the Irish Press reported that James Connolly and his family had emigrated from Anlore near Clones, County Monaghan. These and other assertions were simply attempts to ensure the Irish status of Connolly.4

To confuse matters further, Connolly put ‘County Monaghan’ as his birthplace when he filled out the 1901 census. There are at least two possible reasons why he felt it necessary to give this false information. At this time, he was living in Dublin and as an active socialist he often came under fire for not having an Irish accent. Shouts of ‘he’s not even Irish’ were not uncommon during Connolly’s lectures, and, as such, he might have felt a need to pretend to have been born on Irish soil. Secondly, it is possible that he felt that the British army was still looking for him to complete his military service, but more about this later.

Whatever the circumstances, it is unfortunate that the concern with Connolly’s birthplace should serve as a distraction from his achievements for labour and for Ireland. Nonetheless, for the purposes of definitively proving where the son of two Irish immigrants, John Connolly and Mary McGinn, was born, an examination can be carried out on his birth certificate. James was born at 107 Cowgate, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Due to the march of time and the Edinburgh slum clearances, the actual house of his birth is long gone, but there is a plaque on a wall which reads:

TO THE MEMORY OF JAMES CONNOLLY

BORN 5th JUNE 1868 AT 107 COWGATE

RENOWNED INTERNATIONAL TRADE UNION AND WORKING CLASS LEADER

FOUNDER OF IRISH SOCIALIST REPUBLICAN PARTY

MEMBER OF PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT OF IRISH REPUBLIC

EXECUTED 12th MAY 1916 AT KILMAINHAM JAIL DUBLIN

Beside the new brass plaque are the remnants of the previous memorial, which was vandalised.

Today, the Cowgate area is given over to the world of entertainment, with a plethora of nightclubs and pubs. In James Connolly’s youth, these streets were very much part of a divided society and constituted nothing short of a slum, populated for the most part by Catholic Irish immigrants. It was the centre of ‘Little Ireland’, where thousands of families were living in single-roomed dwellings. Unemployment was high and Connolly’s father was deemed lucky to work as a manure carter for the Edinburgh Corporation. This job was at the lower end of the scale and involved shovelling animal excrement into a cart. It was poorly paid night work, but there is little doubt that the removal of dung from the streets was considered a great necessity. Such was the importance of this work that when the manure carters threatened to go on strike, at a meeting held on 13 August 1861, they received their demands at 10am the following day.

John Connolly was promoted shortly after his third and youngest son James was born. It was a good step up the ladder as Connolly’s father secured the job of lighting the gas lamps to guide the way for Edinburgh’s citizens over her cobbled streets.

Mary Connolly, James’s mother, suffered from ill health after the birth of her first child, John. It seems she had chronic bronchitis and suffered for the next thirty years until she passed away.5

Young James was formally educated in St Patrick’s School, only yards from his birthplace. This was the school that his older brothers John and Thomas also attended. In 1879, at the tender age of eleven, James’s formal education came to an end and he began work as a ‘printer’s devil’. His brother John was employed by the Edinburgh EveningNews as an apprentice compositor, but James, two years younger than him, was employed at more menial tasks. His job entailed cleaning the ink from the huge print rollers and running errands for more senior staff. Later in life, Connolly would call on the skills that he acquired through his immersion in the printing process when he came to publish his own periodicals.

Newspapers were filled with the stories of the Home Rule movement and land agitation in Ireland. These subjects would have been discussed on the streets, in the public houses, and in the homes of Cowgate. Connolly, like most children, would have picked up snippets of information. Later in life, Connolly would study this period intensively and uncover some Irish idealists who would influence his own thinking, such as James Fintan Lalor (1807–49) and John Mitchel (1815–75).

For the majority of Irish citizens, the most important issue concerned the ownership of land. James Fintan Lalor spread the gospel that the ‘entire soil of a country belongs of right to the entire people of that country’.6 He also held that the return of the land to the people was more important than repeal of the Act of Union.

The figures for the huge change in land ownership due to landlords going bankrupt or simply bailing out of the sinking ship are remarkable. One quarter of the land, five million acres, changed hands in the two decades after the Great Hunger. Of course, it was not the tenant farmers who purchased the land. The new landowners were speculators and hard-nosed businessmen. The Catholic Church, for instance, increased their holdings and invested heavily in land.

In 1879 Michael Davitt founded the National Land League of Mayo, as Connolly later pointedly remarked, ‘to denounce the exactions of a certain priest in his capacity as a rackrenting landlord.’7 The priest, a Canon Bourke, had been forced by the National Land League to reduce the annual rent on his estate by 25 per cent. This was a considerable victory for the tenants, but the demand for a reduction in rent was not the sole underlying principle for the establishment of the League. Tenant farmers were agitating for the famous three ‘F’s: Fair Rent, Fixity of Tenure, and Freedom of Sale.

Anglo Irish landlords were being targeted under the cover of night: their houses were under the constant threat of attack, and their herds of cattle and sheep proved easy targets. These ‘agrarian outrages’ were the reinstatement of a tradition from the eighteenth century as an effective but cruel form of protest.

Of a less violent nature, but equally intimidating, was the concept of ostracising landlords or those who collaborated against the Land League. Although not an entirely new idea, it was most effectively and notably used against Captain Charles Cunningham Boycott in 1880. Boycott, an agent for an absentee landlord, not only donated his name to the English language, but required over a thousand soldiers to protect his imported labourers when his tenant farmers refused to harvest the crops from his estate in retaliation for his refusal to reduce rents.

Some years before this, in 1875, the use of the obstructionist policies of Joseph G Biggar (1828–90), a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, was introduced in the House of Commons. A fellow Fenian, John O’Connor Power (1846–1919), and a smattering of other Irish MPs soon joined him. Between them they managed to hold up the business of parliament, to the exasperation of all the other members, by talking for hours and hours on various bills that were under discussion. The father of the Home Rule movement, Isaac Butt (1813–79), did not agree with this policy and considered it to be below the conduct expected of gentlemen. But few could argue that Charles Stewart Parnell (1846–91) was not a gentleman, and when this young Protestant landlord threw his lot in with the obstructionists, Isaac Butt’s popularity began to decline until his death in 1879.

A year later, in April 1880, after a general election, Parnell became the leader of the Home Rule Party. By this stage Parnell had already joined with Davitt when they founded the Irish National Land League. The democratic Home Rule movement and the Irish National Land League were now intrinsically linked. Both gathered strength from each other at the apparent expense of more revolutionary movements, such as the Irish Republican Brotherhood.

However, it would be unwise to presume that the Fenians did not have a hand in this alliance. Davitt, as a member of the Brotherhood, had spoken at length with John Devoy (1842–1928) and other Clan na Gael organisers in America concerning his concept of the New Departure, a uniting of everyone from the Irish MPs to the tenant farmers, the IRB, the clergy, the Irish abroad and at home, all working towards the goal of Irish freedom. It would have been folly for the IRB to plan for an open revolution, considering the disastrous attempt of the Young Ireland movement of 1848, and more recently the failed Fenian uprising of 1867. It was clear that the 1880s and 1890s would be a popular time for the Home Rule Party and the Land League, and if the Fenians had at least a part in this success it could only benefit them.

In order to bring some restoration of order, a coercive bill, the Protection of Person and Property Act, was brought into force in 1881. One of the first uses of the bill was to arrest Michael Davitt, which ironically only helped to secure more monetary support from America. Then the Ladies’ Land League was formed, a considerable milestone considering that women were traditionally excluded from politics. The Land League also stepped up its activities to the extent that William Gladstone, the Liberal Prime Minister, brought in a Land Act. It was unsatisfactory in its own right, but it was accompanied by a new Coercion Act which added to the indignation of the Irish. Parnell did not want to lose the support of the Liberals and the moderates, so he avoided condemning the Land Act outright within the walls of the British Parliament. Instead, he chose to retain the support of the IRB and the more extreme elements of the Irish Parliamentary Party by launching attacks on parts of the Act in newspapers and through public speeches. In an episode reminiscent of today’s political posturing, Parnell called the British Prime Minister a ‘masquerading knight errant’ who was ‘prepared to carry fire and sword’ into Irish homesteads. On 13 October 1881, Parnell was arrested and imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol. He was soon joined by other nationalist MPs such as John Dillon. The editor of Parnell’s United Ireland newspaper, William O’Brien, was also imprisoned.

For those MPs who found themselves imprisoned in Kilmainham Gaol in the winter of 1881–2, their reputation became allied to the revolutionaries who had gone before. Kilmainham Gaol was a political prison. This was the place where Robert Emmet spent his last night before his execution outside St Catherine’s Church on Thomas Street. Emmet’s 1803 insurrection was short-lived, but the iconic image of the young Protestant being hanged and beheaded has remained in folk memory to the present day. Emmet’s evocative final speech from the dock, in which he implores no man to write his epitaph until his country has taken her place amongst the nations of the world is, two hundred years later, considered among the greatest speeches ever recorded. Kilmainham also housed political prisoners in 1848 and 1867.

In May1882 the Kilmainham Treaty was signed, despite the fact that it angered the Fenians who believed that Parnell had surrendered. The Treaty was very informal but involved a promise on Parnell’s part to suppress the violence of the Land War. Gladstone’s compromises included the release of Parnell and the other prisoners, a relaxation of coercion and some minor concessions on the Land Act. The leadership on both sides believed the Land War was effectively finished by the spring of 1882.

During this time of agitation in Ireland, James Connolly’s eldest brother left Scotland. John had taken ‘the Queen’s Shilling’, that is, joined the British army, and was stationed in India. At the same time, James’s father John was demoted to being a carter, which meant that there was less money for the household. Added to this, a factory inspector had being doing his rounds and paid a visit to James Connolly’s place of employment. He soon spotted that James was too young to work at the job he was performing (despite the introduction of a box to give an illusion of height to his small frame); as a result, James was dismissed from the print works. For the next two years Connolly was employed in a bread factory. He once explained to his daughter Nora how crucial it was for him and his family that he have work: ‘I’d have preferred to stay at school. There wasn’t any alternative … the few shillings I could get were needed at home. I found work in a bakery. I had to start before six in the morning and stay till late at night. Often I would pray fervently all the way that I would find the place burnt down when I got there. Work is no pleasure for children …’8

The census of April 1881 shows that the thirteen-year-old James was listed as a baker’s apprentice and that he lived with his brother Thomas and their parents at 2A Kings Stables in Edinburgh. Not long after this, the young baker’s health began to suffer badly due to the extreme physical demands made on him – he was, after all, just a boy. Luckily, he found work in a small mosaic factory where he stayed for a year. It would appear that this was much better employment and kinder to the health, but perhaps insufficiently exciting for a young lad of fourteen. Maybe it was the chance of adventure, or perhaps it was for economic reasons, or maybe it was simply to follow in his brother’s footsteps, that James Connolly falsified his age and enlisted in the 1st Battalion of the King’s Liverpool Regiment. 9 Little information is available on Connolly’s time in the British army due to the fact that he was reticent about this period of his life and because he used a false name when he signed up. However, it is possible to follow his movements to a certain degree. Joining the British army resulted in Connolly returning to the land of his father and mother, for, on 30 July 1882, his battalion was shipped to Cork. This was the first time Connolly had set foot on Irish soil. The Ireland that the fourteen-year-old soldier arrived in, that July, was still concerned with the fate of two men who had been assassinated in Dublin a couple of months beforehand.

Just as the Fenians looked on the Kilmainham Treaty as a sell-out, so too did WE Forster, the Chief Secretary of Ireland. Foster was known for his indecisive nature and was nicknamed ‘The Pendulum’ by those within Dublin Castle circles. For once, he did not swing but made a firm decision; incensed as he was by the British ‘surrender’, he resigned his position. His callousness was not missed by nationalists, but his replacement was not given much time to prove himself worthy to the Irish. On 6 May 1882, Frederick Cavendish had just arrived in Dublin and was taking a stroll home with his second-in-command, the under-secretary Thomas Burke, towards the Viceregal Lodge in the Phoenix Park. Both men were surprised by a radical new group, the Invincibles, whose members produced knives and stabbed the new chief secretary and under-secretary. The Phoenix Park assassinations caused outrage in Britain. Gladstone (related by marriage to Cavendish) would not honour the terms of the Kilmainham Treaty. Instead of coercion being relaxed, a new Act strengthening these draconian laws was introduced. Furthermore, Parnell, despite offering to resign as an MP, found himself under suspicion to the extent that British detectives followed his every move. These detectives reported to their superiors that he was seen in the company of a married woman, Katherine O’Shea (1845–1921), something that would affect Parnell later. Nonetheless, the Home Rule leader’s offer to resign strengthened his reputation amongst the British political figures, and the stand that he took against coercive measures simply served to secure his position with the nationalists.

By December 1882 the Land League was suppressed by the British. The organisation was then replaced by the Irish National League, which came fully under the control of Parnell and the Irish Parliamentary Party. But Parnell was moving away from land reform, soliciting massive donations for the Irish National League and moving more towards the Home Rule issue.

The Ashbourne Act of 1885 enabled more than twenty thousand tenants to borrow the money required to purchase their holdings. This created a temporary period of calm, but the defeat of the Home Rule Bill of 1886 led to a Plan of Campaign where tenants demanded a reduction in rent. Should the landlord refuse, the tenants paid their rent into a fund managed by trustees, who would then use the money for the relief of the evicted. Parnell did not back the tenants on this issue. In 1887, AJ Balfour, as chief secretary, was instrumental in bringing in the Perpetual Crimes Act (or Coercion Act), in an attempt to break the tenants’ spirit. In September 1887 three people were shot by the Royal Irish Constabulary at a tenants’ meeting in Mitchelstown. The campaign by the tenants seemed to win the approval of many trade unionists around the globe, but drew the ire of Pope Leo XIII, who condemned it in an official Papal Rescript. Three more Conservative Land Acts gave further rights to certain tenants over the next few years. This policy of ‘killing home rule by kindness’ would be British policy in Ireland until 1914, and the Land Acts also served to diffuse the Land War.

There may not have been a well organised socialist party, but this does not mean that there were no socialists in Ireland. James Connolly would later write in Labour in Irish History about ‘The First Irish Socialist’, one William Thompson (1775–1833) of Clonkeen, Rosscarbery, County Cork. Thompson was a philosopher and Connolly remarked how unusual this was as he reckoned that the ‘Irish are not philosophers as a rule, they proceed too rapidly from thought to action.’ ‘Thompson’s work as an original thinker,’ wrote Connolly, long preceded Karl Marx ‘in his insistence upon the subjection of labour as the cause of all social misery, modern crime and political dependence …’10

It was not in the barracks that Connolly was introduced to the writings of William Thompson. That would happen later in life, when Connolly was engaged in the process of educating himself. For the moment, in the service of Queen Victoria, he had to content himself with the base nourishment of barrack-room conversations, which most likely did not include political debate. From his descriptions of life in the military, it can be surmised that this intelligent young man had little time for his comrades in the dormitories. Many years later in the Workers’ Republic newspaper, Connolly described the moral atmosphere of a typical barrack room as being of the ‘most revolting character’. The British Army itself he described as a ‘veritable moral cesspool corrupting all within its bounds’.

By September 1884, Connolly and the 1st Battalion were stationed in the Curragh Military Camp in County Kildare, not too far from Dublin. Typically, soldiers on leave would have headed for the comfort of Dublin’s many public houses and then perhaps taken in the sights of Monto, the notorious red-light district of old. It is unlikely Connolly engaged in such behavior as (most unusually for a young soldier) he was teetotal and seldom used tobacco, but it is clear he visited the city. The following year, in October 1885, his battalion moved to the city, and by June 1886 Connolly was barracked in Beggars Bush.

It was around this time that Connolly first encountered Lillie Reynolds. They met on the street when they were both unsuccessful in hailing a passing tram. This may seem unusual to commuters today, but when the trams were Dublin’s main mode of transport; the idea was that potential passengers could hail them at any point on the line. In fact, there was a time when drivers were encouraged to stop beside people and ask them if they needed a tram.

Lillie Reynolds and her twin sister Margaret were born in Carnew, County Wicklow, in 1867. Her father John, a farm labourer, had died at a young age, forcing the family to move to Dublin, to make a living. The twin girls, their two brothers, John and George, and their mother, Margaret, settled in Dublin’s Rathmines district. As a young girl, Lillie entered service with a family called Wilson.

The initial attraction between James Connolly and Lillie Reynolds blossomed into romance, and by the end of 1888 they had decided upon marriage. Lillie was Church of Ireland, but inter-faith marriages were not unusual at that time.

In February 1889, James Connolly left Ireland. The reason behind his departure is unclear. His battalion had been ordered to Aldershot in preparation for an overseas posting, possibly to India. Connolly had only a few months left to serve of his seven-year stint; he made the decision to part company, or go AWOL, from the British army.

Around this time, Connolly’s father had also fallen ill in Edinburgh and James travelled to the Scottish town of Perth, possibly to be able to visit his father. Lillie was to join him at a later date. It was in Scotland that Connolly became involved in the Socialist League and both their lives were to alter dramatically.

Notes

1Workers’ Republic, 8 April 1916.

2 Connolly, James, Labour in Irish History, Dublin, Maunsel, 1910.

3Sinn Féin Rebellion Handbook, Dublin, The Irish Times, 1916, p272.

4 Desmond Ryan also asserts that Connolly was born in 1870, which goes in some way to explain why his official death certificate indicates that he was 46 when he was executed, whereas he was really 47, just three weeks short of his 48th birthday.

5 Greaves, C Desmond, The Life and Times of James Connolly, London, Lawrence & Wishart, 1961, p17.

6Irish Felon, 24 June 1848.

7 Connolly, Labour in Irish History.

8 Connolly O’Brien, Nora, Portrait of a Rebel Father, Dublin, Talbot Press, 1935, p86.

9 Samuel Levenson suggested that Connolly may have joined the Second Battalion, Royal Scots, but the evidence is insufficient.

10 Connolly, Labour in Irish History.

Chapter Two • • • • • •

1889–1896

Married with Children

Governments in capitalist society are but committees of the rich to manage the affairs of the capitalist class.1

In February 1889, not long after arriving in Perth, James Connolly made his way to the more industrialised town of Dundee. His elder brother John, who had been stationed in India with the British army, had served his time and returned to Scotland, and was now heavily involved in the Scottish labour movement in Dundee. Here the socialists were conducting a ‘freedom of speech’ campaign which gained momentum when local courts banned public meetings. The Social Democratic Federation (SDF), the radical Marxist party which had been established in 1881, held huge demonstrations against the ban, and tens of thousands attended. As one of the organisers of the campaign, John Connolly introduced his brother to socialism.

When Lillie arrived in Perth, Connolly had already left for Dundee. She remained for a time in Perth. This was the first of many separations that the couple would endure throughout their lives. A year before their marriage, James wrote to ‘Lil’ from St Mary’s Street, Dundee:

For the first time in my life I feel extremely diffident about writing a letter. Usually I feel a sneaking sort of confidence in the possession of what I know to be a pretty firm grasp of the English language for me in my position. But for once I am at a loss. I wish to thank you for your kindness to me, and I am afraid lest by too great protestation of gratitude I might lead you to think that my gratitude is confined to the enclosure which accompanied the letter than the kindly sympathy of the writer. On the other hand I am afraid lest I might by too sparing a use of my thanks lead you to think I am ungrateful to you for your kindness. So in this dilemma I will leave you to judge for yourself my feelings towards you for your generous contributions to the ‘Distressed Fund’.

So my love, your unfortunate Jim, is now in Dundee and very near to the ‘girl he left behind him’ but the want of the immortal cash and the want of the necessary habiliments presses me to remain as far from her as if the Atlantic divided us. But cheer up, perhaps sometime or another, before you leave Perth if you stay in it any time, I may be available to see you again, God send it. I am glad to be able to tell you that I am working at present though and in another man’s place, as he is off through illness. So perhaps things are coming round. I could get plenty work in England but you know England might be unhealthy for me, you understand.

Excuse me for the scribbling as the house is full of people. It was only across the street from here a man murdered his wife and they are all discussing whether he is mad or not, pleasant, isn’t it. Please write soon. It is always a pleasure to me to hear from you, and especially in my present condition it is like a present voice encouraging me to greater exertion in the future. But I must stop, for I cannot compose my mind to write, owing to the hubbub of voices around me. I will watch for it expectantly, and believe me I will be glad to have the assurance of the sympathy of my own sweetheart.

Yours lovingly, James Connolly2

The reference in the letter to ‘England might be unhealthy for me’ has been taken to refer to the fact that James Connolly was AWOL from the British army.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, there were many different socialist groups in Scotland. It was not unheard of to be a member of more than one organisation and, in fact, Connolly was associated with them all at one stage. Initially, he joined the Socialist League and later he became a member of the Social Democratic Federation.

The Social Democratic Federation was founded by HM Hyndman in 1881. Although the SDF ethos was based on the ideas of Karl Marx and attracted his daughter, Eleanor, as a member, it was not supported by Friedrich Engels, Marx’s long-term collaborator. The party published a popular journal, Justice, to which Connolly would later contribute.

Some members of the SDF found aspects of Hyndman’s leadership unpalatable. For instance, Hyndman was accused of being dictatorial and that he wielded too great a control over Justice. As a result, the Socialist League was founded in 1885 by disgruntled members of the SDF. The League stood for revolutionary socialism and advocated Marxist principles. Early members included Edward Aveling, Ernest Belfort Bax, Edward Carpenter, Walter Crane, Eleanor Marx and William Morris. A journal was also published under the name Commonweal. The party was slow to develop but John Bruce Glasier formed a very large and active branch in Glasgow. By the early 1890s a large anarchist section had secured control of the Socialist League, which drove many of the Marxists back towards the SDF and indeed to the Independent Labour Party.

In 1888, James Keir Hardie, Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham (the first Socialist MP), Henry Hyde Champion, Tom Mann, and other SDF activists formed the Scottish Labour Party. Keir Hardie, a miner, socialist and union activist, was elected to the House of Commons in 1892, where he gained a certain notoriety for his refusal to wear ‘acceptable attire’ (black frock coat, silk top hat and starched wing collar) in parliament. Instead, he wore a plain tweed suit, a red tie and a deerstalker. He called for the abolition of the House of Lords, votes for women and often attacked the British monarchy in his speeches. The following year Hardie was instrumental in founding the Independent Labour Party. The objective of this party was ‘to secure the collective and communal ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange’; they also called for an eight-hour working day, pensions for the sick, elderly, widowed and orphaned, free education to third level, and universal suffrage. The Edinburgh branch of the ILP was known as the Scottish Labour Party, and would one day have James Connolly as secretary.

There was yet another organisation by the name of the Scottish Socialist Federation, a mixed bag of societies and SDF supporters who worked alongside the ILP to ensure that it did not waiver from its socialist principles. John Leslie became the Edinburgh secretary of the SSF. Connolly was heavily influenced by Leslie’s speeches and his 1894 pamphlet, The Present Position of the Irish Question. Leslie was a few years older than Connolly but they had a lot in common; they were both Cowgate boys, more Irish than Scottish, and, in fact, had attended the same school. From 1894 the SSF produced the Labour Chronicle and Connolly replaced Leslie as secretary. The SSF was calling itself the Edinburgh branch of the SDF by 1895.

A little over a year passed between leaving Dublin and the marriage of James to Lillie. The fact that Lillie was of a different faith did not delay the marriage to any great extent, as permission was sought from the Catholic Bishop of Dunkeld. The lack of finance available to the couple at the time was a problem. Connolly was struggling to feed himself and unable to save the money required to set up home. Although this year was mostly spent apart from each other, the couple continued their courtship by letter. Lillie left Perth and spent a large part of the year working in London. In the meantime, Connolly was employed on a temporary basis as a carter for the Edinburgh Cleansing Department. He wrote a letter, several days before his wedding, expressing his concern, in no uncertain terms, that his bride establish ‘legal residence’ in Perth in order to marry there. He appears to have been more familiar with the exact nature of the laws concerning marriage than he was with his sweetheart’s age. His letter describes preparations for a strike and it is clear that these matters are set to demand his time and attention, despite his pending nuptials:

Lil, I was very glad to receive your letter as it lifted quite a load off my heart. I was so afraid you had not gone to Perth. Your last letter was so very indignant with me. I am amused to see you are getting some of the anxiety which I have had this long time. But you need not be afraid. Mrs Angus is wrong. Six weeks was the old law but that has been altered in 1878. If you had done what I told you and gone to the registrar at once, you would have found out for yourself. Seven days is the time now, so please lose no time and go at once, and if all goes well I shall be with you next week and make you mine forever. When giving your name to the registrar I gave it as Lillie.

By the way please write at once as soon as you get this letter and tell me your father and mother’s names. Also your father’s profession. I want it as soon as ever I can get it also your birthplace. When I gave your age I gave it as 22, was I right. How I am wearying to get beside you, and hear your nonsense once more. It is such a long time since we met, but I trust this time we will meet to part no more. Won’t it be pleasant.

By the way if we get married next week I shall be unable to go to Dundee as I promised as my fellow-workmen in the job are preparing for a strike on the end of the month, for a reduction in the hours of labour. As my brother and I are ringleaders in the matter it is necessary we should be on the ground. If we were not we should be looked upon as blacklegs, which the Lord forbid. Mind don’t lose a minute’s time in writing, and you will greatly gratify your loving Jim. Not James as your last letter was directed.3

The wedding ceremony took place on 30 April 1890 in the Roman Catholic Church, Perth.4 The groom moved his new bride into his room at 22 West Port, Edinburgh.

The couple found a great friend in John Leslie, secretary of the Edinburgh branch of the SDF, who spoke at many of the ‘freedom of speech’ meetings in Dundee. Connolly listened and learned much from John Leslie, and not only joined the SDF but became one of their evangelists. Leslie described how Connolly first came to his attention:

I noticed the silent young man as a very interested and constant attendant at the open-air meetings, accompanied by his uncle whom I knew to be one of the Old Guard of the Fenian movement, and once when a sustained and virulent personal attack was being made upon myself and when I was almost succumbing to it, Connolly sprang upon the stool and to say the least of it, retrieved the situation. I never forgot it. The following week he joined our organisation, and it is needless to say what an acquisition he was. We shortly had five or six more or less capable propagandists and certainly cut a figure in Edinburgh, but with voice and pen Connolly was ever in the forefront. When he started … he had a decided impediment in his speech which greatly detracted from the effect of his utterances, but by sheer force of will he conquered it …’5

In May 1891, James’s mother Mary finally succumbed to the chronic bronchitis that had marred her health since the birth of her first child. She was fifty-eight years of age and would not live to see James and Lillie’s first child. Mona Elizabeth Connolly was born on 11 April while the young parents had rooms in Mary Street at the east end of Cowgate, Edinburgh.

Not being the most salubrious of neighbourhoods, Cowgate had little to recommend it, and in an effort to better their living standards the little family moved to number 6, Lawnmarket, a continuation of High Street. From here they moved into number 6, Lothian Street. This lodging was in a congenial neighbourhood where there was a high population of students and intellectuals, with bookshops and colleges nearby.

As an example of how deep his involvement in the movement was, Connolly’s home on Lothian Street was used for meetings of the Scottish Socialist Federation. This also gives an indication of the low numbers of activists; probably so few that they could all sit around the Connollys’ kitchen table. Nonetheless, their dedication, and indeed Connolly’s resolve, was more than enough to make up for their small size. Throughout the rest of his time in Edinburgh, Connolly’s home was often the official headquarters for whatever party he was involved with. Lillie must have been a very patient person to contend with the regular visitors, especially considering that a second baby, Nora Margaret, arrived on 14 November 1893. This was the year that the Edinburgh branch of Keir Hardie’s ILP formed, calling themselves the Scottish Labour Party. Connolly also became involved with them while remaining a member of the SSF.

In August 1893, Secretary Connolly announced in Justice that the SSF were going to form a branch in the seaport of Leith. His acerbic attack on the citizens of Edinburgh is a fine example of his early writing, a style which he rarely deviated from throughout his career:

The population of Edinburgh is largely composed of snobs, flunkeys, mashers, lawyers, students, middle-class pensioners and dividend-hunters. Even the working-class portion of the population seemed to have imbibed the snobbish would-be-respectable spirit of their ‘betters’ and look with aversion upon every movement running counter to conventional ideas. But it [the socialist movement] has won, hands down, and is now becoming respectable. More, it is now recognised as an important factor in the public life of the community, a disturbing element which must be taken into account in all the calculations of the political caucuses.

Leith on the other hand is pre-eminently an industrial centre. The overwhelming majority of its population belong to the disinherited class, and having its due proportion of sweaters, slave-drivers, rack-renting slum landlords, shipping-federation agents, and parasites of every description, might therefore have been reasonably expected to develop socialistic sentiments much more readily than the modern Athens.