Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

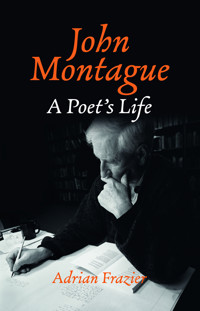

In the late twentieth century, Irish poetry achieved an historic quality, a golden era to compare with the verse of the Elizabethan and the Romantic periods. A Poet's Life is the definitive biography of one of the first and foremost poets in this golden generation, John Montague. Inspired by the examples of Yeats and Joyce, he consciously educated himself to play a central role in the self-understanding of his people. Ahead of the public recognition of such issues, Montague wrote personally about abortion, divorce, alcoholism, domestic violence, and clerical abuse in education. His poetry offered to others release from a painful past. Out of where he was most hurt, his best work issued. When the Troubles erupted in his home province, he was to the forefront in engaging with events directly, sometimes in a cross-community effort with fellow poets of the other faith. This record of his life is also an intimate, familial account of modern Irish poetry and its precision, documentary basis, and reliable chronology, it is sure to become a vital conduit into a body of poetry that will never be forgotten. Already a highly lauded biographer, Adrian Frazier was a close acquaintance of Montague for more than forty years. In this fully authorised narrative that is clear, candid, and marbled with humour, Frazier reveals the sources of poetry in Montague's life and traces the progress of his style from book to book. Based on Montague's archive of private papers, and informed by the counsel of the poet's lifelong friends, partners, and fellow poets, this is a monumental work of Irish literary biography, sure to be a classic of the genre.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 943

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

John Montague

A Poet’s Life

John Montague

A Poet’s Life

Adrian Frazier

THE LILLIPUT PRESS DUBLIN

First published 2024 by

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

62–63 Sitric Road,

Arbour Hill,

Dublin 7,

Ireland

www.lilliputpress.ie

Copyright © Adrian Frazier, 2024

Home Truths sequence of poems © Estate of John Montague, 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher.

A CIP record for this title is available from The British Library.

Hardback ISBN 978 1 84351 910 2

eBook ISBN 978 1 84351 925 6

Lilliput gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Arts Council / An Chomhairle Ealaíon.

Set in 11pt on 16 pt Adobe Garamond Pro by Compuscript

Printed and bound in Sweden by Scandbook

To Thomas Redshaw

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Preliminary Considerations

Garvaghey, County Tyrone: His Primary School

Doing Time in Armagh at St Patrick’s College

University College Dublin and His Fraternity

Yale, Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Berkeley and Madeleine de Brauer

Baggotonia and His First Two Books

The Dolmen Miscellany

and the Second Irish Revival

The Berkeley Renaissance and the Free Love Movement

Paris in ’68 and the Meeting with Evelyn Robson

Flight to Cork, Fatherhood, and

The Rough Field

University College Cork and a Rising Generation of Poets

Tired of ‘The Troubles’ but Trying to Get to the Bottom of

The Dead Kingdom

Home Truths

and Unprintable Poems

Coming Apart in America: the State Poet of New York

The Years in Nice and Vagabonding with Elizabeth

Home Truths [an unpublished sequence]

Illustrations

Bibliography

Endnotes

Index

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

‘What about Tom Redshaw?’ John Montague asked in May 2015 when we first discussed my undertaking to write his biography. We would work on it together, I said.

In fact, Tom and I did collaborate from beginning to end. Redshaw was not just Montague’s bibliographer and the most productive scholar of his poetry, he was a Montague family friend from the late 1960s onward. He is himself at work on a biography of Liam Miller, publisher of The Dolmen Press, so the two of us were up to our elbows in many of the same archives. The collaboration deepened our friendship and gave us both pleasure. This biography is rightly dedicated to Thomas Dillon Redshaw.

The biography of a recent contemporary largely depends on the quality of the archive and the reports of witnesses. Montague was a careful record-keeper of his own writing life. Through most of his mature life, he kept a daily diary in which he recorded not just appointments, addresses and the like, but also ideas for stories and drafts of poems. When the composition of a poem moved to a full-sized page, he often spelled out models, listed possible themes, and gave advice to himself. Various drafts would normally go into a folder, along with newspaper clippings, reviews, photographs and other materials related to the poem. The folders themselves would usually be stashed within the covers of a published volume of his work.

Although poetry itself does not often bring in significant royalties, research libraries will sometimes spend a considerable sum to acquire the papers of a prominent poet. Montague sold his archive in four tranches: in the 1970s to the University of Victoria, British Columbia; in the 1980s, to the State University of New York at Buffalo; and in the 1990s to the National Library of Ireland. The remainder of his papers went to University College Cork.

These archives contain not only his working papers but his correspondence. The age of serious letter-writing is now in the past. In his time, Montague kept up exchanges about works-in-progress with a number of scholars and writers. Chief among these are the letters to and from Barry Callaghan, Barrie Cooke, Donald Fanger, Serge Fauchereau, Thomas Kinsella, Liam Miller, Timothy O’Keeffe, Thomas Parkinson and Richard Ryan. These are sometimes letters of five, ten, or fifteen pages of seriously considered writing (Montague often made several drafts of his letters, and left some important draft letters unsent). I am grateful to Fanger, Fauchereau, and Ryan for making available to me their own files of Montague correspondence, and to the libraries that hold the letters of the other correspondents.

For a candid understanding of Montague’s personal life, I am beholden to his companions who have either allowed access to their letters in Montague’s various archival collections, or themselves provided letters and diaries, and afterwards replied to my questions, particularly Susan Patron, Elizabeth Sheehan and Janet Somerville.

The insight of Montague’s closest friends over the years was often my guide. Barry Callaghan, Serge Fauchereau, Richard Ryan, Philip Brady and Tom McGurk met with me for interviews, sometimes on several occasions. Thomas McCarthy, by publishing his own journals (both in excerpts and in a book), has enriched everyone’s understanding of the poet; McCarthy also responded helpfully to my enquiries. Other Cork writers lent assistance, particularly Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, Patrick Crotty and Greg Delanty, who sat down for extensive interviews.

For family history, I largely relied upon Andrew Montague, the son of the poet’s brother Turlough. Resident in Fintona, and with immense local knowledge, he was scrupulous in his assistance. He made it clear that if this biography were uninformed or inaccurate, it would not be his fault. He located key official documents as well as telling me things that had never been written down. His sisters Dara and Sheena, and his brother Turlough, as well as his cousins Peter and Mary, also contributed.

Montague has three surviving widows, Madeleine, Evelyn and Elizabeth. Each took me in hand and told me how things had been and where I had made a mistake. Evelyn gave me three afternoons of serious conversation. Elizabeth prepared a personal memoir, in addition to granting an interview and answering many enquiries. They all offered notes on the complete draft. I tried to show John as they saw him, as well as how he imagined them. The daughters of John and Evelyn, Oonagh and Sybil Montague, contributed by interview, telephone and email.

My friend and neighbour, the poet Eva Bourke, lent an ear if I felt the need of a reality check on some matter. She read the manuscript in draft and asked the right questions. Martin Carney, my father-in-law, born about the same time as Montague, read the chapters as they were written, and gave his honest opinion of the man and of the unfolding story. Sometimes he was able to illuminate for me a bygone aspect of Irish life, such as the mating customs of Irish dance halls or the teaching practices of national schools. Kevin Barry, Professor Emeritus of University of Galway, did a friend’s duty in reading early sections and giving me a green light to continue.

My literary agent (and long-time friend) Jonathan Williams involved himself with this book to a remarkable extent. He had also been the agent for John and Elizabeth Montague. He knew the entire literary scene I was attempting to describe. He put me in touch with a number of witnesses I may otherwise never have found. When the manuscript began to take shape, he read drafts and made scores of notes, three times. I have tried not to let him down.

There are many to thank. The distinguished witnesses who took the time to help include the following (no doubt, I have accidentally failed to credit some others): Jennifer Airey, Guinn Batten, John Behan, Richard Bizot, Eva Bourke, Kevin Bowen, Kevin Barry, Jodi Boyle, Anthony Bradley, Phil Brady, Rory Brennan, Tom Burns, Christopher Cahill, Caroline Callner, Matthew Campbell, Cliodhna Carney, Martin Carney, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Frances Clarke, Mary Conefrey, Evelyn Conlon, Valerie Coogan, Liadin Cooke, Patricia Coughlan, Vincent Crapanzano, Katharine Crouan, Jacques Darras, Howard Davies, Margaretta D’Arcy, Alex Davis, Gerald Dawe, Seamus Deane, Greg Delanty, Louis de Paor, Máirín Ní Dhonnchadha, Tony Carroll, Denis Donoghue, Lelia Doolan, Theo Dorgan, Stephen Ennis, Peter Fallon, Serge Fauchereau, John FitzGerald, Ger Fitzgibbon, Michael Foley, Lawrence Fong, John Wilson Foster, Roy Foster, George Frazier, Joe Gagen, David Gardiner, Alessandro Gentili, Seán Golden, Fiona Green, Nicholas Grene, Eamon Grennan, Christopher Griffin, Elizabeth Grubgeld, Brendan Hackett, Gerry Harty, Elizabeth Healy, Jefferson Holdridge, Alannah Hopkin, Brendan Horisk, Frank Horisk, Barry Houlihan, Ben Howard, Catherine Howell, Destiny Hrncir, Marian Janssen, Pierre Johannon, Dillon Johnston, Colbert Kearney, Suzanne Keen, Aidan Kelly, Patsy Kelly, William Kennedy, Frank Kerznowski, Thomas Kilroy, Jane Kramer, David Lampe, James Larkin, Brian Lawlor, Catherine La Farge, Adrienne Leavy, Conor Linnie, Mary O’Sullivan Long, Edna Longley, Michael Longley, Frances Lynn, Sean Lysaght, Rory MacFlynn, Jim MacKillop, Derek Mahon, Dennis Maloney, Liam Mansfield, Lara Marlowe, James Maynard, Thomas McCarthy, Bill McCormack, Hubert McDermott, Lucy McDiarmid, Hugh McFadden, Avice-Claire McGovern, Paula Meehan, Frank Miata, Conor Montague, Paul Muldoon, Helena Mulkerns, Deirdre Mulrooney, Gerry Murphy, Patsy Murphy, Eoin O’Brien, Peggy O’Brien, Dáibhí Ó Cróinín, Cronan O Doibhlin, Eamon O’Donoghue, Colette O’Flaherty, Timothy O’Grady, Seán O’Laoire, Mary O’Malley, Ed O’Shea, Paul Perry, Lionel Pilkington, Laetitia Pollard, Christopher Reid, Christopher Ricks, John Ridland, David Rigsbee, Clíona Ní Ríordáin, Maurice Riordan, Frank Rogers, Jim Rogers, Seamus Rogers, Richard Ryan, Elizabeth Sheehan, Frank Shovlin, Tony Skelton, Janice Fitzpatrick Simmons, Jordan Smith, Gerard Smyth, Janet Somerville, Rod Stoneman, Steven Stuart-Smith, Gary Snyder, Eoin Sweeney, ColmTóibín, Emer Twomey, Irving Wardle, Robert and Rebecca Tracy, William Wall, Barbara Weiner, David Wheatley, Mark Wormald, Nina Witozek, Vincent Woods.

I am grateful for the professional help and courtesy of the special collections’ staff at the following libraries: John J. Burns Library, Boston College; The Poetry Collection, University at Buffalo; Shields Library, University of California at Davis; Cambridge University Library; James Joyce Library, University College Dublin; Boole Library, University College Cork; Rose Library, Emory University; James Hardiman Library, University of Galway; National Library of Ireland; Brotherton Library, Leeds University; Elizabeth Dafoe Library, University of Manitoba; Maynooth University Library; Library of the State University of New York at Albany; McFarlin Special Collections, University of Tulsa; McPherson Library, University of Victoria; Reynolds Library, Wake Forest University; Library of the University of Washington in Seattle.

For permission to quote from Montague’s archive I am grateful to Elizabeth Montague, his literary executor, and for permission to quote from his published works, to Peter Fallon of The Gallery Press.

PRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS

Not long after beginning to work on the life of John Montague, eight years ago, I was asked Why are you writing about him? Why not Seamus Heaney? Isn’t he more famous? A little snort of laughter might have been heard on the slopes of Parnassus, whether it was John elbowing a ghostly Seamus in the ribs, or the other way round. Not to detract from the merits of Seamus Heaney, as gentleman or poet, but there are advantages to John Montague as a subject for a literary biography.

His course in life offers a full view of post-war poetry, not just poetry in Ireland, but a vantage-point on modern poetry in America, Britain and France. Do you know the parlour game ‘Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon?’ The actor was in everything, or next door to it. Montague is the same among poets. Allen Ginsberg? In 1955 Montague was in Medieval English class with him at Berkeley, just a month before the first reading of Howl. Harold Bloom? Montague was his classmate at Yale University in 1953, when Bloom talked endlessly and with rabbinical profundity.

At the Iowa Writers Workshop, the other student poets included Robert Bly, W.D. Snodgrass, Philip Levine and James Dickey; one of his instructors was John Berryman. In Berkeley, he had an affair with a woman running an art gallery; one of the artists she represented was ‘Jess’, who turned up at her dinner party with his partner, the poet Robert Duncan.

Poetry, of course, is not a matter of who you know. That’s the point made by Patrick Kavanagh’s poem ‘Epic’: ‘I have lived in important places, times/ When great events were decided,’ such as a neighbour shouting, ‘Damn your soul!’ as another farmer raises a potato spade in anger. Nonetheless, Montague’s nose for cosmopolitan literary life makes for a narrative that illuminates not just his own poetry, but modern poetry in general. When important things were just breaking into flower, he was often a witness, a participant, a change agent, sometimes even the leading contributor. That was in New Haven, Iowa City, Berkeley, Dublin, Paris, Cork city, Belfast and New York. Particularly in his home country, he was a path-breaker.

2

To write a proper literary biography you need more than just a writer of interest. It is necessary to have the materials, the traces of works-in-progress, living witnesses, observers in the past who left memoranda, and a full archive of correspondence. Where Montague is concerned, the evidence is there. Conscious of what Yeats’s archive looked like (from Allan Wade’s 1955 edition of the Letters), he became a professional curator of his own papers. He kept letters he received, and drafts of many that he sent. Then he sold off his so-called ‘complete archive’ not once, or twice, but four times. Poetry had in that period acquired status; it was, to borrow a phrase from T.S. Eliot, the definition of culture.

When Montague was starting off in university, serious literature was rising towards this peak of prestige. In America the GI Bill sent veterans to college. To help them, in the late 1940s Harvard’s president Robert Maynard Hutchins created a Great Book publishing scheme. The seeds of Western Civilization – recently rescued from Nazism at the cost of fifty million lives – were thought to be found in literary works: the best that has been thought and said. From the early 1950s, partly due to the nature of New Criticism, lyric poetry acquired the highest status of all literary forms.

In a cultural parallel of the Marshall Plan, a group from Harvard, often led by Jewish literary critics and writers like F.O. Matthiessen and Saul Bellow, set up the Salzburg Seminar in Austria. This was meant to be an introduction for Europeans to the new post-war world: a high-minded combination of American literary modernism with constitutional democracy and free speech. Montague was a scholarship boy at this seminar in the summer of 1950. In his own words, he became a ‘fellow-traveller’ of these American anti-communist liberals.

From the mid-1950s he kept up a number of literary correspondences – chains of letters back and forth that may be ten pages long. On his own side, Montague would often do an outline, and then a first draft, before producing a legible and coherent fair copy of the letter posted. Some of his key correspondents were the following:

Donald Fanger, met at Berkeley in the 1950s, later Harvard professor of the European novel;

Serge Fauchereau, French critic and cultural historian;

Robin Skelton, English poet, magician, anthologist and Yeats scholar, later professor at University of Victoria in Canada;

Thomas Kinsella, fellow Dolmen Press poet and rival;

Tim O’Keeffe, London editor and publisher, at MacGibbon and Kee;

Thomas Parkinson, poet, historian of Beat poets, and Yeats scholar at University of California, Berkeley;

Barrie Cooke, Anglo-American painter long resident in Ireland;

Richard Ryan, Irish poet and diplomat;

Liam Miller, printer and publisher at The Dolmen Press;

Barry Callaghan, Toronto poet, journalist and editor of Exile.

Montague’s letters are occasions for self-examination, with point-by-point plans for improvement. A biographer would never have access to such hours of self-invention if the letter had not been written, and having been written, saved.

The poet was himself a magpie, snatching up bits and pieces to make his nest bigger and bigger, but the eggs over which he brooded often took a long time to hatch. He collected preparatory materials – newspaper articles, photographs, phrases written on a bank statement or bus ticket, false starts. He kept all these bits and pieces in a sheaf, and would go back over them time and again – in pencil, ballpoint, or fountain pen. ‘What is the point of this?’ he might ask himself, or ‘Why not end this here?’ An early habit was to list two or three models for the work in progress, often the work of a contemporary, such as Charles Tomlinson, Thomas Kinsella, Robert Lowell, or Robert Duncan. He kept abreast of what his contemporaries were doing.

Montague is a peculiarly conscious and scholarly poet. He sometimes states the intended theme of the poem on the manuscript page. On occasion, he would then cross it out, and suggest to himself a different theme; he had misunderstood his own poem in progress – it was going somewhere else. Composition is fluent, molten, bubbling, sometimes going to sleep for months or years, before reawakening and erupting again. It is not uncommon in the case of a Montague poem for eight or ten years, even fifteen years, to pass between a poem’s first appearance in a notebook and its publication in a volume. ‘All Legendary Obstacles’ was eleven years in the making from first to last.

In the archive, one may see the poet at work. That is the meat and drink of a literary biography.

3

At the origin of Montague’s poetry is his motherless loneliness as a small boy in Garvaghey, County Tyrone, away from parents and brothers, enduring a stammer that arose suddenly and mysteriously. Although he turned out to be a bright lad, coming at or near the top in several subjects in national scholarship competitions, the doors to many professions were closed to him simply because of his inability to speak up. He was not going to be a priest, a barrister, a medic, or any public-facing occupation. All through university he never spoke in class.

The laborious perfection of a spoken utterance is the very definition of poetry. Montague came to see that he could sort out his feelings by way of meditation, organize his thoughts, then fix them word by word on paper. This was the medicine for what ailed him. It was also a way of making himself intimately understood, first to himself, and perhaps some day graspable and attractive to another.

In the lecture rooms of University College Dublin and around the portico of the National Library, any student with a taste for verse could sense the loitering ghost of James Joyce. Someone like them – Catholic, Irish, nearly penniless, but bookish – had from this very place begun a journey to recognition as a hero of European letters. Dublin was beginning to see the traffic of American professors looking for clues on to how to understand Joyce. They were noticed in the pubs and bookshops, people like Hugh Kenner and Richard Ellmann. And asking about Yeats too; in fact, especially Yeats. To be a poet in ways only the elite could completely appreciate, that would be a very fine thing, and evidently not impossible for an Irishman.

But how was one to do it? Nowadays, a person could apply for instruction in a writing programme, or buy a how-to manual in paperback. In the late 1940s, when Montague was becoming serious about his poetry, there was just one guidebook, and it was a most eccentric one. Published at Faber by T.S. Eliot, The White Goddess addressed itself specifically to young men who wanted to know how to write a great poem. There was only one way to do it, according to this book. Robert Graves had boiled down the story of Yeats’s life into a formula. The secret was to fall in love with a woman not your wife, a woman in whom the Moon-goddess has taken up residence. This superior, whimsical being will break your heart to pieces. You will try but you will never master her, yet she will give you the training and experience you require to write a great poem. In her you will encounter the tragic, beautiful mystery of life itself.

The White Goddess was a formative book not just for Montague, but for Thomas Kinsella, Michael Longley, Derek Mahon and Ted Hughes, and for Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton among the women poets of the period. Many Americans – Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, and W.S. Merwin, for instance – moved to Majorca to be near to the cliff-dwelling bard and trickster. Montague himself made the pilgrimage in 1963. And in 1975, he brought the old man for a grand tour in Ireland, the country in which Graves had first learned to walk and to speak English.

The Muse theory is no longer on the recommended reading list for young poets; far from it. Apart from the fact that it equates the poetic life with serial adultery, it is difficult to say which contemporary sin it most indulges: idealizing a woman or objectifying her. No educational treatise could be more sexist. It directly told women not even to try to be poets. As for the critique that the apprehension of a woman by a Muse poet is always superficial, one would have to investigate the case poem by poem. The original Gravesian notion of the Muse is founded in awe and curiosity about the other. Many outcomes are possible.

When the women’s movement got underway – the seventies in America, and the eighties in Ireland – poetry continued to play a key role. Lyric self-expression was a central activity of feminist ‘consciousness-raising sessions’. But the path to which Robert Graves had pointed as the only road to take was closed. The story of how one Gravesian male poet dealt with this triumphant feminist critique makes for an interesting chapter in literary history.

4

One other dimension of Montague’s poetic practice that became more clearly visible as a result of biographical research was the role of magic. When he was a visiting writer-in-residence in the mid-1960s at UC Berkeley, Montague was asked to give a public lecture on Yeats. In the course of his remarks, he struck a condescending note, like that of W.H. Auden, concerning ‘the pitiful, the deplorable spectacle of a grown man occupied with the mumbo-jumbo of magic And the nonsense of India’. Robert Duncan, sporting a cloak, with many rings on his fingers, rose to indignantly defend the centrality of magic to all great poetry. Montague was delighted by this apparition of a present-day necromancer. He followed up the subject in his friendship with Duncan, who brought him around to bookshops specializing in the occult in San Francisco. Montague added his name to their mailing lists.

The magician side of Yeats’s practice was also cultivated by Montague’s friend Robin Skelton. He rose to a position high in the echelons of West Coast warlocks, who, wearing pentagrams, milled about the colleges of Vancouver as well as San Francisco. A glance at a list of Skelton’s dozens of non-fiction books indicates how his interest shifted from scholarship to creative writing manuals and finally to handbooks on magic. In Montague’s Collected Poems he too often builds his lyrics on the fundamental speech-acts that underlie magic spells, what J.L. Austin called ‘performatives’: sentences that don’t say what they are doing; they do it. They bless, curse, apologize, promise, name, lament and command. A ritualized performative can make things change: bring about peace, sleep, sexual desire, consolation, or terror.

For that period, this interest in the lost magical powers of speech was not particularly eccentric. Many poets educated themselves about archaic paths into the depths of human experience – through dream, myth, drugs, music, even choric movement. Technicians of the Sacred was the title of a popular California anthology of such approaches. In A Slow Dance the poet-figure certainly takes the shape of a shaman. That is also true of Seamus Heaney in the contemporaneous North, of Ted Hughes in Wodwo, and of Galway Kinnell in The Book of Nightmares. Robert Graves himself consulted with Carlos Castaneda after the publication of The Teachings of Don Juan, and came away with his own small stash of peyote buttons.

5

One Modernist who loomed large over the post-war generation, but has since sunk into the waters of academic Lethe, was Ezra Pound. His Pisan Cantos had won the first Bollingen Prize for American Poetry in 1949 at the time Montague was starting an MA on Austin Clarke. On his list of books bought in 1951, one is The Poetry of Ezra Pound. There Hugh Kenner begins what he completed twenty years later in The Pound Era, the argument that Ezra Pound was the key to twentieth-century modernism, someone without whom there would have been no Waste Land, and maybe no Ulysses either. Without Pound, Robert Frost may have otherwise gone unnoticed by the mandarins and William Carlos Williams remained out of touch with artistic developments beyond New Jersey. Even Yeats got a second life, and broke free from the Celtic twilight, Kenner observed, after a sharing a cottage one winter with Pound. Hugh Kenner tended to overlook Pound’s antisemitism and the obviously treasonous character of his wartime conduct; he also failed to admit just how boring and truly bonkers were the economic ideas that choked up the pages of the middle Cantos. But he did highlight two things about Pound that continued to interest Montague.

The first is that it is still possible for a poet to aim for the historic capstone of a major career: the epic, a poem containing history. In the last dribs and drabs of The Cantos, Pound would admit that he had failed: ‘I cannot make it cohere,’ even though, he grumbles, ‘it does [somehow] cohere’. That left it to a younger writer to write a long poem that was neither boring nor insane and clearly did cohere. Montague pondered several possible models (e.g., the Mississippi novels of Faulkner, as well as Goldsmith’s The Deserted Village), and began the poem in May 1961. It took him eleven years to complete The Rough Field. But he had in that time learned how to write a long poem as a symphonically orchestrated sequence of lyrics in various modes with a set of guiding mythic images. Having learned to do it, he wrote one after another: The Great Cloak, The Dead Kingdom and Border Sick Call. This is a mighty achievement.

The second thing Montague picked up from Pound is that a literary movement does not come to pass by accident – a few people of talent happening to be born around the same time in one locality. There is, necessarily, a role for the impresario, the caller of meetings, the editor of anthologies, the reviewer of contemporary works. Yeats himself excelled in these roles from the 1890s, but Pound – particularly as depicted by Kenner – was the exemplary cultural activist. When confined in an Italian concentration camp, Pound became aware of the grotesque failure of his own political plans, but he was still proud of his cultural work: ‘to draw from air a live tradition/this is not vanity’. That is a phrase often quoted by Montague.

When Montague returned to Dublin after his five years in the USA, he found it ‘dead as doornails’. Along with Liam Miller, Montague took upon himself the role of kicking it back into life. The flowering of The Dolmen Press, the launching of a new generation of Irish writers in The Dolmen Miscellany, the novelty of public poetry readings, the establishment of Garech Browne’s Claddagh Records, the spoken word recordings of Clarke, Kavanagh, Montague, Heaney, Kinsella and others, the avant-garde vibrancy of the Lyric Theatre’s magazine Threshold, which quickened back into life many Ulster writers and made a place for new ones, the Planter and the Gael tours of John Hewitt and Montague, the creation by means of his Faber anthology of a bilingual back story for contemporary Irish poetry, the Irish Studies department at UCD – John Montague had his long and pointy beak in all these activities.

Taken all together, they make up a ‘Second Irish Revival’. That is not a name given in retrospect, so that after sixty years we can say, ‘In the 1960s, there began to be a real cultural renaissance in Ireland.’ That was the name Montague gave it beforehand. The phrase occurs again and again in his correspondence with, among others, Liam Miller, Robin Skelton and Donald Fanger. There is a certain special skill in being a mover and shaker, and part of it is the ability to take pleasure in the flourishing of others. Montague had that special skill. The lonely boy without his family always wanted to be part of something bigger, something both happy and prosperous. He brought it to pass not just in Dublin but in Cork too.

6

One key aspect of contemporary poetic practice had no root in Irish society at large: personal candour. Montague encountered the more confessional side of the lyric early on, in 1955 at Iowa, where his classmate W.D. Snodgrass was beginning to write the poems published in Heart’s Needle. That was the book that inspired Robert Lowell, and later Anne Sexton, to write poems of psychological crisis.

Montague rose to the challenge of this more candid way of writing, but he altered it. He treated his own case not simply as that of a patient in the course of therapy, but in the diagnostic manner of W.H. Auden, as symptomatic of cultural neurosis on a national scale.

He created a form of autobiographical quest narratives with a political aim; the importance of this invention is underappreciated. Long ahead of the public acknowledgment of such issues, he wrote personally about abortion, divorce, alcoholism, domestic violence and clerical abuse in education. In this way, he offered to others release from a painful past. His ambition was not just to be a poet, but to be a healer.

7

A few words must be said about the technical problem presented by this particular biography – that I knew John Montague myself.

I first met him, along with Garech Browne, in the Bailey pub in Dublin in 1973, and again in Cork in 1977 for a published interview. He began to spend the winter semesters in upstate New York in the late 1980s, near where I was teaching, so we met frequently thereafter. Our paths later crossed in Galway, Dublin, Cork and Nice.

While it is helpful to personally know your subject, in a scholarly biography the narration usually does not have a first-person dimension. Compare the situation to a film. You have seen the movie, but you do not know what the face of the cameraman looks like. He was by definition always there and always out of shot. I could not be the objective, scholarly third-person narrator up to the year 1973, or 1977, and then suddenly pop up, crossing in front of the camera, so to speak. That would be not only unbecoming but a technical mistake.

So I put a factually based scene into the first chapter in which John, at the very end of his life, tells me about a key incident in those years, the day at Garvaghey primary school when he first suffered his speech impediment. The reader will be unlikely to reproach me for having passed along his words. After appearing in the first chapter, it does not seem quite so strange that I should later sometimes reappear in the role of witness and reporter.

One further drawback of a biographer being a friend of the subject would be that you would find it hard to reveal things about him that were true but discreditable. In John’s case, however, I knew he would want me to pay particular attention to what some would keep hidden, just as he had done. I simply had to follow his example of ruthless intimacy and maintain a pitiless fidelity to the blizzard of specific data that is a personal life, in pursuit of a portrait notable for the intimacy of its apprehension. That is what I owed him.

It is easier to tell the truth about your subject if your real purpose is to tell the story of how the life turned itself into the achievement of the poetry. The poetry is above the poet, and in terms of public interest if in no other way, the poet is above the teacher, the lover, the father, the husband and the brother. John conceived of himself as the parent of the being that brought the poems into existence; he, at all times, served that growing child. He dedicated his life to becoming the author of his books. There is a cost in that, one paid by himself and others. A biographer cannot be blind to the harm, or hide it from the reader, but ultimately, one has to remember that the reason a book is being written about John Montague is that he wrote the poems. Otherwise, this long intrusion into his private life would be unjustified.

What I did not have to do is to act like a manager in a human resources department, and weigh the complaints filed about the subject against the sum of his credits, or imagine that, in his shoes, I would have lived his life better than he did. My goal has to be to capture his life story in its uniqueness, and, at the same time, to quote Samuel Johnson, to reveal ‘the uniformity in the state of man’: that ‘we are all prompted by the same motives, all deceived by the same fallacies, all animated by hope, obstructed by danger, entangled by desire, and seduced by pleasure’.

Adrian Frazier, September 2024

1

GARVAGHEY, COUNTY TYRONE: HIS PRIMARY SCHOOL

Figure 1: The Cameronia

1

Not long after the three boys were put on board the Cameronia, on 5 May 1933, Johnnie, the youngest, aged four, came down with measles. He was taken from third-class quarters to a bed in the infirmary, a compartment stinking of disinfectant. He was not suffering all that badly; he felt special, pleased by the attentions he was getting. A woman on board, missing her own child left behind in America, came to bring him caramels in the evenings. The ship’s doctor gave him coloured cards from his cigarette packs; Johnnie played games with them on his counterpane. He did not miss the days on deck with his older brothers, Seamus, eleven years old, and Turlough, nine. The sight of the heavy sea on the first day was a fright. Years afterwards, however, he would sometimes dream of another voyage, one shared by all three brothers.1

Bound for Liverpool, the Cameronia slowed after rounding Malin Head in Donegal and sounded its horn at the mouth of Lough Foyle on 10 May. A tender came out to receive the Irish passengers.2 From third-class accommodation they disembarked: nine housewives, three of them with children, several labourers, a cook, a grocer and a 56-year-old man retiring to Bunbeg, County Donegal, plus the three Montague brothers. At the port of Derry, two different parties were waiting for them.

In New York, following the death of the boys’ uncle John Patrick Montague from liver disease a month earlier, Jim and Molly (Carney) Montague quickly decided that they could no longer take care of their three children. Jim would have to find paying work, and Molly, often ailing, suspected even of having tuberculosis, could not manage the household on her own. Their prospects were poor. The Great Depression hung over America. There was no relief there. They would have to arrange to foster the children out with family back home in Ireland.

Before his death, Uncle John had been the breadwinner for the extended family at 56 Rodney Street in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. An enormously popular fellow, he met emigrants off the boat in New York. Playing his fiddle, he welcomed them back to his drinking parlour – ‘speakeasy’ was the term for it during the Prohibition years. Patriotic, piously Catholic and charismatic, John was the heart of a little community of emigrants from Tyrone, cousins, in-laws, former neighbours, Irish civil war refugees from Ulster.

On 10 April 1933 the mourners bundled into funeral coaches following the hearse that carried John slowly from the Church of Our Lady of Good Counsel out to St John’s Cemetery in Long Island: his brother-in-law Tom Carney and wife, Eileen, Bridget and Catherine Quinn, the McGarrity brothers, James and John, several Caseys, McLaughlins and McRorys.3 Times had been hard; they looked as if they were about to get harder.

The plan was that the oldest son, Seamus, would lodge with his maternal grandmother, Hannah Carney, the widow of an auctioneer and spirit merchant in Fintona and herself a sound businesswoman. She ran a private loan business (funding Catholics who could not get bank mortgages, in order to buy land). She also rented out cottages in ‘the back lane’. When they were infants, she had helped care for Seamus and Turlough, before Molly left to join her husband in America in 1928. Hannah Carney agreed by post to take the oldest, but just the one. What about the other two? They could go to Jim Montague’s sisters in Garvaghey, Brigid and Winifred (‘Freda’). They lived nine miles from Fintona in the old two-storey family house, alongside the Omagh Road. Neither was married. They would be glad to make a home for the two lads.

Maybe no one explained these plans to the boys themselves – how they were to be shared out between the Montague aunts and the Carney grandmother.4 At the pier in Derry, faced with separation from Seamus, Turlough kicked up a fuss, and refused to go with Aunt Brigid and Aunt Freda. He wanted to return with his big brother to Fintona, the town where he had been born. He got his way, and Hannah Carney wound up with Turlough too.5 The two aunts, contented with their sole prize, closed around the bewildered smallest boy.

That was how John Montague ended up growing up apart and alone from both his parents and his two brothers from the age of four.

2

Figure 2: Aunt Freda Montague and Johnnie, 1933.

After Brigid and Freda made the trip from Derry back to Garvaghey, snapshots were taken. In a photo in front of the little Austin 7, Freda stands behind Johnnie, her hands protectively on his shoulders. Already shaping up to be a tall, slope-shouldered lad, pale-skinned and with the characteristic squinched yet radiant look about his eyes, he is wearing a white, short-pants ‘onesie’ with a scalloped collar, nearly sleeveless. He had been wearing it since leaving Brooklyn. He came with one other outfit, too big for him as yet, woollen knickerbockers with matching jacket and leather brogues, nothing like the clothes of other children around Garvaghey.

The other snapshot shows Johnnie and Aunt Brigid on a grassy hillside behind the house. There is a note in Brigid’s hand on the back of the photograph: ‘Johnnie had been rolling down the hill & wanted me to do the same’ (there being no brothers to play with).

Under her black headscarf, Brigid wears a pleasant, affectionate wry grin, her arm encircling Johnnie’s waist. Looking at the pair of them, a person wouldn’t need to be told they were family: nearly all the Montague features are there, narrow face, high cheekbones, aquiline bone structure, though here Brigid alone has the nose John would have to grow into, and their russet colouring cannot be seen in a black and white photograph.

Figure 3: Aunt Brigid and Johnnie in Garvaghey.

The local school at the top of the hill was still in session in the middle of May, but the boy had only turned four at the end of February, and was just getting over measles. He had but newly arrived in a strange place. Classes could wait until autumn. Now was a time for rest and play.

For his room, they gave him the place of honour, the bedroom of his grandfather and namesake.6 John Patrick Montague had died in 1907, aged sixty-seven, leaving his widow with nine children. In addition to James and John, the brothers who had gone to Brooklyn, and Brigid and Freda still on the farm, his heirs included Tom, in 1906 a student at St Patrick’s College, Armagh, but in 1933 a Jesuit priest in Australia, and Anne, Kate, Mary Agnes and Teresa.7 Old John Montague had been a Justice of the Peace, no common thing for a Catholic in the Unionist north. He was also betimes a teacher, farmer, Belfast businessman and Redmondite supporter of moderate parliamentary nationalism. His funeral was a big event in County Tyrone: ten priests gathered for the obsequies, a dozen Justices of the Peace and solicitors, and postmasters from across the region, along with various branches of the Montagues and all the householders along the Broad Road.8

Figure 4: John Montague, J.P. (1840–1907) and family. The poet’s father, James, is seated on the ground, to the left.

He left £900 at his death (about €130,000 today), but his 117-acre property was tied up in an unusual will.9 It was the Irish custom to leave the house and farm to the oldest male descendant, in order to ensure the survival of the family plot of land, but John’s will provided that each of his children was entitled to bed and board in the house that he left to his wife. Apart from Brigid and Freda, by 1933 the inheritors of old John P. Montague had scattered. Anne married a Mr Sheridan, and lived seven miles up the hill in Altamuskin; Kate had become Mrs MacKernan; Mary Agnes had a family with John O’Meara in Abbeylara, County Longford; Teresa was a nun in a convent. If family fortunes had fallen, or spilled out over the earth, they might gather and rise again. The two aunts cherished great hopes for little Johnnie, the new master.

Johnnie did not know any of this yet. The strangeness of his situation overwhelmed his powers of understanding. But he was, he later judged, ‘patient as an archaeologist’.10 He observed little things that ‘he had to grow old to understand’.11 There were ancient-looking books in the room, photographs on the mantelpiece, a trapdoor into the attic. He could overhear the grown-ups down in the kitchen. There would be time to explore. Mysteries awaited him.

He was put to bed after his six o’clock supper, in a large old wooden bed. The hours of summer daylight are long in Northern Ireland, much longer than New York; it doesn’t get dark until after 10 pm in May. John later recalled lying disconsolately ‘watching the fading lights on a group of slight spiky pines’ opposite his window. The silence would creep across the lawn, the shadows of the pines coming inch by inch into the room. Above his bed hung a picture of his grandfather; there was another of the Holy Family. A rushy St Brigid’s cross was tacked on the wall. Outside, there was no honk of taxi or ding-ding-ding of the trolley he had known in New York, just ‘the curious whisper of the wind’.12

He did not settle easily. He had night terrors for years. When he began to try to write poetry in college, he often tried to get at that eerie witching hour of the summer evenings in early childhood. One unpublished draft was evidently patterned after ‘Time Was Away’ by Louis MacNeice:13

The door swung open and the window darkened,

And I looked up without knowing why:

The door swung open and a hinge creaked,

What was behind the door and why?

The door swung open and I looked up,

Hand unsteady, causing a blot:

The door swung open and something touched the latch

And something moved in the passage which

Was there and yet not alive.

A shadow climbing a rickety stair,

A ghost in the cellarage with its unheard cry,

A slight suspiration – terrible, shy.

And the cat looked up from the saucer of milk,

Her slight eyeballs moving like glinting silk,

Across the floor moving on trembling pads

White, white mouth open and delicate cry.

As in the room and behind the door

The dark things moved, gross as a boar

Horned and heavy and with triplicate heads

The thin crying of evil in the night outside.

3

When morning came, there was much about the Montague home place to interest a boy. In the farmyard behind the house was a byre, a long turf shed, stalls, a manger and a chicken coop. The Montagues kept a horse called Tim. Johnnie stared at the great lip slurping water at a tank. The horse’s big barrel sides were scarred with the welt of the leather harness. Dropping his head, Tim nibbled at a dock leaf.14

Johnnie’s aunts had a dairy cow too, and Freda milked it morning and evening; that was worth watching. Up on the hill a flock of turkeys grazed. When Freda came out of an evening to feed the fowl, she would shake corn in a metal pail and the turkeys came ‘zooming over the hedges … thirty of them, red-faced and sharp-beaked with flapping uneven wings … landing on their splayed claws to come running full tilt across the level ground’.15 The ducks in the farmyard scattered to make way for them, then crowded back in to peck the corn sprinkled over the ground. A farmyard was a place of wonders for a child straight from Rodney Street, Brooklyn.

The house itself turned out to be not just a farmhouse. It was a post office and lending library too. Brigid, with her wire-rimmed spectacles, was the qualified postmistress, her literacy a service to the whole community. ‘White-haired, gaunt as a rake, she stood in her little office among the weighing scales and postal regulations, indicating where his or her mark should go.’ She patiently listened to callers’ tales of long-drawn-out family quarrels and offered her ‘sweet assurance’.16

Others came to buy odds and ends from what had been, in earlier decades, a flourishing shop. One family still came regularly – ‘one or other of seven nearly identical children lugging a basket as big as himself across the fields’ – because they had quarrelled with the new grocer, a more up-to-date business, half a mile up the hill. Although the post office and shop were meant to close at three in the afternoon, people came at all hours and were never turned away.

While Brigid was postmistress, Freda was honorary librarian; the house was a branch of the Carnegie Library for County Tyrone. A hundred books came each quarter and were arranged ‘in wooden cases with hasps like pirate trunks’. Inside were treasures – sixty volumes of fiction, twenty juvenile and twenty general knowledge. Once ranged on the half-empty shelves, they began to smell, the boy thought, like the meagre groceries, sweet and musty, with damp on the bindings. By the time he was ten, Johnnie had become a serious bookworm and those who came to borrow a volume consulted him as unofficial deputy librarian – at least on all categories besides love stories; they were Freda’s department.17

Borrowers asked, ‘Is there any love in it? Your aunt said the last was good, but there was damn all love in it.’

‘There’s plenty this time,’ Johnnie would say, hedging.

‘Is it good love or the other sort?’

‘The other sort,’ he would answer, just guessing what it was they were after.

Several local boys recall Freda as being a ‘tough woman’, even ‘sharp, harsh, dictatorial’.18 Brigid was gentler; she was a great one for the prayers. Young Frank Horisk would come in to borrow a book, and he just had to wait until Freda saw fit to come in from the kitchen. After sizing up the customer, she would put a book on the counter and say, ‘There … Take that – that’s for you.’ He had no other say in the matter. Of course, when it came to little Johnnie, once he took up reading, he had the run of the shelves.

There was a story behind Freda’s love of love stories, and her grumpiness. In her twenties, she had been a popular lass – a Gaelic Leaguer, ‘girl courier of Cumann na mBan’, step-dancer, amateur actress and pianist; she was a prize-winner at nationalist fleadhs.19 Even into the time after Johnnie joined the household, she would take the stage at local concerts to sing an Irish ballad and dance a hornpipe. Every Sunday she played the organ in church and also took charge of the choir.

In the early 1930s Master MacMahon, the teacher in Roscavey, used to call in to borrow a book, and then stop to chat with this talented girl. Her hopes of matrimony were soon pinned on Jim MacMahon.

Before Johnnie’s arrival, Brigid and Freda let their father’s old bedroom to a tenant. They had mortgage payments due monthly; every little bit of income helped. When a new teacher arrived for Garvaghey school, she took the room, an attractive woman with a fine singing voice, named Celia. After the pretty lodger was moved out to make room for Johnnie, Celia was seen in the neighbourhood on the arm of Jim MacMahon. Indeed, Freda raged that the Garvaghey schoolmistress was to be found lying in ditches with Master MacMahon, ‘all the ditches of the county’.20 It was bad enough for Freda to lose her chance at wedding one of the few educated gentlemen of the parish, but to have him stolen from under her nose, and by a schoolteacher ever-afterwards present in Garvaghey village, not a big or populous place – that was a bitter gall. Freda’s ill-starred romance was another thing not explained to little Johnnie.

4

As the months of summer rolled on, Johnnie was allowed the run of the farm. He would go up with Freda and the little collie to bring the milk cow to the barn. Later, he might walk up alone with the dog and watch over the cattle. Around 1950, when he was beginning to write poetry, he described one of those lonely moments of childhood when he was dreaming by himself. Never published, it reads like a hitherto undiscovered poem by Patrick Kavanagh:21

The spot where I lay in the furze bush

And read about spaceships and watched people pass

…

Rattle of lorries on the road passing at night

Dog sitting by the grassy verge in the twilight

The kind of love you feel moving in the byre

Where the chickens cheep and the hens settle themselves

The light dim in the kitchen from a candle on the sideboard

The ducks quacking in expectation of food.

In all these sounds you have accompaniment.

Soon will be the time of milking and foddering.

A boy alone in the house, he wanted more ‘accompaniment’ than his dog and the barnyard fowl. Across the Broad Road, he could see Austin Lynch and his brother Gerard. He would like to go barefoot with them on hot days up the Broad Road to Kelly’s shop and get a candy for a halfpenny; he too would like to stick his toes in the bubbling tar. Opposite, there were the rundown stables of Broughan House, a former halt on the Dublin–Derry coach road.22 It would be fun to climb through those places with the Lynch brothers, or go down to splash in the Garvaghey river.

Yet his aunts were slow to let him mingle with the other children in the townland. It was not just that he was too young, or that he did not yet know his way about. They thought him a class above the locals and destined for great things.

Nonetheless, they could not but give him more rope as time went by. Aunt Freda dated his acceptance of Garvaghey as home, and her acceptance of him as a villager, from the time he raced back to the house, late and out of breath, saying he had been ‘keppin’ the cows, who had taken fright because somebody ‘coped’ a cart.23

In September he started attending Garvaghey Primary School, up the hill, on the south side of the Catholic church. There is a photograph of the schoolboy dated June 1934, at the end of his first year.

With the black cat in his arms, his curls brushed out and hair parted, he is wearing the woollen short pants, matching jacket with flapped pockets and knee-socks that had come with him from Brooklyn to County Tyrone.

He made a friend at school, a girl, to judge by ‘A Love Present’, a story in which she is called ‘Mary’. He was allowed to play with the children of her family; they owned the new shop at the crossroads.24 Mary was the eldest and on her account Johnnie accepted as his pals her puffy-faced little brothers. He fancied her swinging pigtails, and teased her, and believed she liked him back. By the time the school inspector made his visit, both were picked out as prize students. The teacher put them through their paces. In the classroom skit, she was Little Red Riding Hood and Johnnie got to play the wolf.

The following school year, Johnnie came down with something in his chest. For a month he was kept at home. The novelty of being sick soon wore off and he waited for a visitor; he waited for Mary. Finally, Freda called upstairs that someone had arrived to see him. He hung over the banister to see if it was Mary. It wasn’t. It was a girl from the back of the class, a child from a labourer’s cottage. She had often waited like a spaniel after school in the hope of talking to him.

‘Tell her to go away,’ the boy cried out.

The grown man saw, in pain, his ‘arrogant, precious little spirit’,25 the prince of his aunts’ dreams.

5

It is impossible, decades later, to do justice to the experience of a small child. Here, the story of John Montague’s first years arises from a few public records, such as passenger manifests, stray mentions in old newspapers, some surviving snapshots, recollections by his surviving neighbours and family lore. Over and above these are Montague’s own efforts to recapture in words the self he possessed upon first becoming conscious. His experience was such as to make him ask the questions, Who am I? What am I? For answers, he was alert to clues in his surroundings. He also looked inward. Interiority was darkness, mystery, rich in possibilities. At certain junctures later in life, a window appeared to open between things outside and things inside. These rememberable moments arose for him as ‘spots of time’. During certain favourable hours, he could mentally go back to Garvaghey and watch things happening as if he were still there, but his former self remained other, to a degree incomprehensible. The boy in the past was holding, metaphorically speaking, an antique Persian brass lamp. Even so, the genie inside it, the active magic, if present, was hidden.

What returned to him were often occasions of shock: the terror of lying alone in bed in the endless evening twilight; the first consciousness of shame upon doing wrong to another; stabs of loneliness and a longing to run with others and be just like them; the looming presences ‘like dolmens’ of the old people in the village; a consuming alertness to the quick alterity of different embodied beings, horses, dogs, the white-mouthed cat, barnyard fowl, aunts.

In practice, this search among scenes of childhood for the medicine for one’s soul follows the example of William Wordsworth.26

There are in our existence spots of time,

That with distinct pre-eminence retain

A renovating virtue, whence, depressed

By false opinion and contentious thought,

Or aught of heavier or more deadly weight,

In trivial occupations, and the round

Of ordinary intercourse, our minds

Are nourished and invisibly repaired …

For Wordsworth, these renovating sources existed in childhood, not afterwards; and among scenes of nature, never in towns or cities; and when one was alone with one’s self, not with a gang of others. All this came home to John Montague. Garvaghey was the cradle of his selfhood.

If Montague was a lifelong Wordsworthian, he also grew to be a citizen of the age of Freud. For Freud, it is often not the radiant spots of time from the past, but the blank areas of the unconscious that shape the self. What we do not recollect, and cannot, may like a dark star cast its gravitational force over our course in life. People’s ‘childhood memories’, Freud believed, are mainly formed much later, around puberty, in a complicated process of remodelling, analogous to the process by which a nation constructs legends about its early history.27 These so-called childhood memories take the form of scenes – tableaux – but the pictures do not really show the past; they screen it from view. Something falsely recalled, magnified out of proportion, masks yet another memory, one of greater emotional importance, difficult to face.

Montague accepted the importance, for the sake of one’s mental health, of recovering the reality of what happened in childhood. It is often shame, sometimes about matters of sex, at other times about class, poverty, unbelief, unmarried female pregnancy, contagious sickness in the family, or physical disabilities, which cause families to repress painful truths. As a result, a lot of the emotional history of the Irish people is obscured. Daniel Corkery spoke of ‘the Hidden Ireland’ as rural Gaelic-speaking communities that persisted into the eighteenth century; but there is another sort of hidden Ireland, one made up of all the subjects culturally deemed secret and locked behind walls of silence and shame. In his mature poetry, Montague gave direction to his sequences and short stories by turning them into quest romances of a particularly therapeutic kind, in pursuit of revelation of the hidden.

The last time I talked with John Montague, in early October 2016, two months before his death, was in a hotel in County Derry, before his return with his wife Elizabeth to Nice, France.28 His voice was breathy, hoarse, nearly inaudible, but his mind was sharp. He had, he said, been trying to hunt down in the Linenhall Library, Belfast, a copy of a book he had been asked to read from in Garvaghey School. He had a picture in his mind of the page, how the print was laid out and the Victorian line drawing that illustrated the passage. He had written a poem about it long ago, ‘Obsession’. It was most important that he locate the book.

When the schoolboy was moved to the senior side of the Garvaghey School, the headmistress, Celia MacMahon, told him to stand and read out a passage to the class; she had heard tales from his previous teacher of him being precociously literate.29 He stared at the page. He knew the meaning of the words, but not the experiences described – they were, he recollected, disturbing, scary, sexual. In his 1967 verses on this moment of recurrent terror (‘Obsession’), he writes:30

Once again, the naked girl

Dances on the lawn

Under the horrible trees

Smelling of rain

And ringed Saturn leans

His vast ear over the world;

But though everywhere the unseen

(Scurry of feet, scrape of flint)

Are gathering, I cannot

Protest. My tongue

Lies curled in my mouth –

My power of speech is gone.

Trembling in the classroom, he tried to tackle the passage, but the first syllable stuck in his mouth. He bobbed his head, craned his neck to spit out the words. He flung himself at it again, but failed to break through to speech. The other children watched him struggling, the top boy in the class struck dumb. Mrs MacMahon told him to get on with it. But he couldn’t. That must have been how it was, the minute, the hour, the day he lost his ability to speak freely.

He wanted me to know that Mrs MacMahon was a beautiful woman, and dressed well, in form-fitting clothes. Her singing voice was entrancing. It may be that she had teased him about the remaining traces of his Brooklyn accent, or his woollen outfit from New York, now too small for him; he was not sure about that. Maybe she had it in for him, on account of the high and mighty pretensions of the Montagues in the Lilliputian hierarchy of Garvaghey; or because of the old feud with Freda and her rancid gossip. He was ignorant of that background when he was a little boy.

Mostly, it was the passage itself: how could she ask a little boy to read a thing the like of that?

Like what? I asked.