13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Nonsuch Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Kathleen Ferrier has a reputation as the greatest lyric contralto of the twentiety century. Her story, from her humble beginnings as a telephone operator in Blackburn to the height of international fame as one of the world's leading concert artists and her untimely death at the age of forty-one, is told told with compelling insight and perception, using a variety of sources, from photographs, diaries, and private letters to the memoirs and recollections of those who knew her best. Despite having no formal musical training, Kathleen worked with all the celebrated conductors of the time, and is remembered for her performances of music by Brahms, Schubert and Mahler, as well as a handful of operatic roles. Enlarging considerably on many alternative biographies, this excellent account captures the warmth, humour and charm of a figure whose astonishing life and career proved to be, sadly, all too brief.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

KATHLEEN

To Geoffrey Handley-Taylor, FRSL

KATHLEEN

THE LIFE OF KATHLEEN FERRIER 1912–1953

MAURICE LEONARD

Maurice Leonard studied drama at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama and singing with the Russian soprano Oda Slobodskaya. For over a decade he was associated with television’s long running series This Is Your Life during which he worked with such diverse subjects as Dame Kiri te Kanawa, Lord Mountbatten, Frankie Howerd and Muhammed Ali.

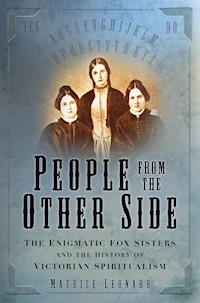

His other biographies include Slobodskaya, Mae West: Empress of Sex, Markova the Legend and Montgomery Clift. He is currently working on People from the Other Side, a history of Spiritualism centred around the legendary Fox sisters.

First published by Hutchinson in 1988

This edition published by Nonsuch Publishing in 2008

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

© Maurice Leonard 1988, 2008, 2012

The right of Maurice Leonard, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8317 7

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 8316 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Foreword by Elisabeth Schwarzkopf

Preface by Winifred Ferrier

Introduction by Maurice Leonard

I The Pianist

II The Singer

III The Diva

IV Orpheus

Epilogue

Discography

She that comes late to the dance

More wildly, must dance, than the rest

Though the strings of the violins

Are a thousand knives in her breast.

A while there was the voice to cry,

A while there was the hand to touch

And if they did not understand

It may be that we asked too much.

Two verses by Tennessee Williams dedicated to Kathleen Ferrier © The Estate of Tennessee Williams

Foreword

I sang in three cities with Kathleen Ferrier. First, in Manchester under the direction of Sir John Barbirolli in the Messiah; second, in Vienna, where we performed the B Minor Mass [Bach] and the Missa Solemnis [Beethoven] under the direction of Herbert von Karajan with the Wiener Philharmoniker and then (if my memory doesn’t betray me) we subsequently went with those two events to La Scala, Milan.

To speak about the last performance first—it was one of the very few times I saw Herbert von Karajan burst into tears, when Kathleen sang the ‘Agnus Dei’. I also remember going to lunch with her in a nearby restaurant—which now no longer exists—when she told me the most excruciatingly funny stories of her experiences within our profession. She had a huge laugh and people turned their heads towards us—no mean achievement considering the normal din in Italian restaurants!

Of the Vienna performance, I know of an unissued record and I am very proud that I can still listen to my voice mingling with hers.

But the greatest experience of all was when she stood on the platform in Manchester sending out her message as the contralto soloist in the Messiah. It seems to me now—and did then—that there was a prophet speaking through her singing, or some other such super-human person. I can only repeat what we would call in German a Binsen-Wahrheit [truism], which applies to her above all others: there are great singers but very few geniuses whom you recognise after hearing one note—Kathleen Ferrier was one such genius.

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf

Preface

When my sister, Kathleen Mary, was born in a small village in Lancashire, no one could have foreseen that she was to become a world-famous singer. Yet, looking back, it seems clear that our family background, her early life, the impact of the Second World War and her own great gifts all contributed to the development of the person and the artist she became. Kathleen describes very clearly how it all happened, often in her own words: the ups and downs, the successes and failures that are an inevitable part of a singer’s life. Her reactions are illuminating and sometimes extremely funny. Descriptions of concerts, reproductions of press notices and the comments of her colleagues and friends, all go to make up this touching picture of a unique artist.

Kathleen was always completely absorbed in whatever she sang. Although in solemn music such as Bach’s St Matthew Passion and the B Minor Mass, in Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius or Brahms’s Four Serious Songs, she expressed her deepest thoughts and feelings, in recitals she could convey a great variety of moods. She would come on to the platform, tall, beautiful, her eyes sparkling, her very appearance telling the audience that they were all going to enjoy themselves. Whether she sang sad or happy songs she held everyone enthralled.

At the height of her career Kathleen was stricken by cancer and the author tells how she faced it with incredible courage. I went to many of her concerts and she never showed the slightest sign that there was anything wrong with her. Singing was the one thing she wanted to do and she was determined to do it, come what may. Knowing how serious her condition was, I was always amazed that she could sing ‘O Death, How Bitter’ and the Rückert songs with such heart-breaking passion and sincerity. Now I think that perhaps it was her way of facing an intolerable situation.

From her earliest days Kathleen was a joy to me, and I consider myself very fortunate to have been her sister. Some of the love that she inspired has rubbed off on me, and over the years thousands of people have written to me about her and for many she has become a symbol of all that is good and brave.

Many of those people who value her records nowadays never heard her sing in person. Many were not even born when she was alive. So it seems strange that there is still so much interest in her and her work. Perhaps there are some obvious reasons for this. Her voice was a lovely natural contralto, immediately recognisable and full of warmth. Her words, whether in English, Italian, French or German, were always clear and she sang a wide variety of songs which appealed to many different tastes. She found in song the perfect way of expressing herself, her gaiety, her love of people, her spirituality. But there is something else … something that cannot be expressed in words, but only in music.

Maurice Leonard is one of those who is too young to have heard Kathleen singing in person, but he too has been captivated by her records. Realising his enthusiasm, I have been happy to let him have access to Kathleen’s diaries, letters and press notices and I am sure that this biography will be welcomed by all those who want to know more about Kathleen Ferrier.

Winifred Ferrier

Introduction

I first remember hearing Kathleen sing when I was fourteen. Her death was announced that day and, in tribute, BBC radio played her recording of ‘What Is Life’. Not such an inappropriate choice as it might seem as she had made what virtually amounted to a hit record out of that eighteenth-century Gluck aria, and it is now permanently associated with her. Kathleen’s voice is instantly recognisable and could never be confused with anyone else’s. But it was not just the gorgeous voice, it was the way she sang which was unique, and its effect on me was personal and moving.

Shortly afterwards an uncle and aunt came to visit. My uncle looked down in the mouth. He was upset, my aunt explained, because his ‘girlfriend’ had died. That ‘girlfriend’ was Kathleen, whom he had never met but regarded, as did many others, as a personal friend. Years later I told Winifred, Kathleen’s sister, this story. She had heard similar anecdotes before: ‘She was everyone’s girlfriend,’ she said. My family were no great musicologists—they enjoyed a good tune but, to them, Kathleen was something special.

When she sang all musical barriers disappeared, whether her audience consisted of great maestros like Bruno Walter and Herbert von Karajan, in the great concert halls of London, New York, Paris or Rome, or of a callow fourteen-year-old listening to the radio at home.

The aim of this book is to try, in some way, to repay Kathleen for what she has given me. When I started my research, one of the first calls I made was on her teacher Roy Henderson. I confessed to him that I had never seen Kathleen on stage and he tartly informed me, ‘Then you only know a quarter of what she did. You had to see Kathleen to know what she was all about.’ Doubtless, but some of us, by virtue of our tender years, must remain underprivileged. Hopefully, this biography will increase peoples’ knowledge of her as a person.

I could not have written Kathleen without help from many people. First and foremost I must thank Winifred Ferrier, who gave me access to all Kathleen’s personal and business letters, many of which have never been published, and to Kathleen’s diaries. Winifred wrote her sister’s biography in 1955, but since then much new material on Kathleen and, literally, dozens of letters which she had written to friends have come to hand. Several attempts have been made to write a more up-to-date book on Kathleen, but these have all been resisted by Winifred, as has an attempt to make a feature film of Kathleen’s life. Winifred is very protective towards her sister’s memory and it was only after a lengthy period following my initial approach, during which I had proved myself loyal to Kathleen, that cooperation was forthcoming. Since then the floodgates have opened. Winifred has not only been cooperative, she has given me a great deal of practical help and advice for which I am deeply grateful.

I would often work for hours at a time in Win’s little dining room, where most of her files on Kathleen are stored. There, long into the night, I would immerse myself in Kathleen’s diaries and letters. There were several framed photographs of Kathleen on the walls and behind where I sat, hanging from the door, was a heavy green brocade evening dress, which Winifred had made for her, and which Kathleen wore many times for recitals, notably during her American debut. The hem at the back is worn where it has brushed over the boards of numerous concert hall floors.

When I returned home I would often play Kathleen’s records for a couple of hours or more and as soon as I woke up in the morning, I would put the records back on the gramophone. A day rarely passed when I did not write about her, listen to her records, read her letters or talk about her to those who had known her.

This research period stretched over three years, and was quite an adventure. Initially Win provided me with contacts by going through her address book and giving me the whereabouts of those of Kathleen’s colleagues who were still alive. They, in turn, gave me other addresses, or directed me towards previously untried avenues of investigation, and so it went on until I had built up a formidable pile of anecdotes, memories and opinions.

I must also thank Bernie Hammond, Kathleen’s former secretary and nurse, who lived with Kathleen during the last eighteen months of her life. Bernie’s response to my initial enquiries was spiky and it was only after a protracted, and intense, cross-examination that she too agreed to help. Then she opened her heart to me and forwarded a 150-page document consisting of the copious diary she had kept for the period she had spent with Kathleen. None of this material has ever been published before.

I had a stroke of luck when interviewing Sadler’s Wells Opera’s principal soprano, Joan Cross. She had sung with Kathleen in Kathleen’s first opera, and readily contributed her memories as well as providing me with a useful research tool by handing me, almost as soon as I had crossed the threshold of her Saxmundham cottage, a huge leather-bound scrap book full of cuttings of Kathleen. ‘This was obviously meant for you,’ she told me. Apparently, someone had given her the book, recently, knowing she had worked with Kathleen. It had been bought at a village jumble sale. Whoever the original compiler was, I am indebted to him or her, for it contains hundreds of clippings, many from small provincial papers, which were largely unavailable from the current newspaper clippings services I had already consulted.

Contralto Nancy Evans, was also helpful. As well as appearing at Glyndebourne together, she and Kathleen had toured extensively, sharing rooms. It is easy to see why the two women got on so well, for she too has a great sense of humour.

Another contralto, Gladys Parr, was also a joy. At ninety-one, she was deaf as a post, but full of memories and joie de vivre. We shrieked at each other until I was hoarse.

On the first occasion I called on Roy Henderson, who was then eighty-one, he was in the garden building a conservatory. Over tea, he gave me some cakes which he had baked himself to a recipe from Gerald Moore. His music room not only contained a framed photograph of Kathleen as Orpheus, but also the piano where they had worked together, notably on the role of the Angel in The Dream of Gerontius.

I am also indebted to John Newmark, of Montreal, who was Kathleen’s accompanist over several years. He sent me many long, personal letters which Kathleen had written to him, again none of which had been published. He had intended using these in his own autobiography, but due to ill-health felt that he was unlikely to be able to make a start and gave them to me instead.

In addition to the above, I must thank certain other people and organisations, among them: John Amis; Helen Anderson; the late Dame Isobel Baillie; Blackburn District Library; the Rt Rev Cuthbert Bardsley; Lady Barbirolli; Alan Blyth; Paul Campion; Annie Chadwick; Benita Cress; Andrew Dalton, John Parry and Michael Letchford of Decca Records; Peter Diamand; Victoria Dunne; Peter Feuchtwanger; Michael Garady; Kitty Harvey; Fred Maroth of Educ Media Associates of America; Walter Foster of Canada; Leon Fontaine; Dr Howard Ferguson; James Ivor Griffiths, FRCS; Lord Harewood; Susannah Jacobson; John Laurie; Adele Leigh; Alison Milne; the late Gerald Moore; my editor, Kate Mosse of Century Hutchinson; K. A. Newton, FRCP, FRCR; Peter Orr; Catherine Parnall; Burnet Pavitt; Lin Pritt; Roy Purkess; Anne Ridyard; Hans Schneider; Donald Scholte; Elisabeth Schwarzkopf; Desmond ShaweTaylor; Bernard Taylor; Gordon Thomson; Dame Eva Turner; Jo Vincent; the Bruno Walter Memorial Foundation; John Watson of EMI; the Trustees of the Tennessee Williams Estate; Wyn Wilson and William Wordsworth.

Maurice Leonard

I

The Pianist

One

In her brief career, Kathleen Ferrier became one of the best loved of British singers. The transition from telephone operator in Blackburn, Lancashire, to internationally famous singer, in demand by the world’s leading conductors and composers, was a magnificent achievement.

In 1953, the year of her death, she could have taken her choice from offers to sing in countries throughout the world. She was already booked for appearances in Africa, and for a coast-to-coast tour of America. Stravinsky had offered her the first performance of a new work, and Toscanini was hoping she would sing for him at La Scala. Herbert von Karajan was trying to induce her to appear in a new production of Tristan and Isolde at Bayreuth, and Benjamin Britten was so anxious for her to record his canticle Abraham and Isaac that engineers were sent to her bedside when she was too weak to go to a studio.

It was all to no avail. The cancer, against which she had fought so valiantly, finally gained its victory, killing her at the age of forty-one.

Kathleen Mary Ferrier had been in a great rush to get into the world. Indeed, the doctor who delivered her vainly called ‘Hold back’ to her mother as the flaxen-haired child slid into his hands. It was almost as though Kathleen knew she had a lot to get through in the short time allotted her.

Kathleen, or Kath as the family called her, was born at No 1 Bank Terrace, Higher Walton, Lancashire, on 22 April 1912. Mahler had died the previous year, and Benjamin Britten, with whom she was later to work so closely, was born the year after.

Apart from the speed of her delivery, no remarkable circumstances attended Kathleen’s birth. She was the fourth child of William and Alice Ferrier. Their first child had been stillborn, and this may have made Alice overprotective of the surviving three. Her father William was headmaster of the local All Saints’ School. While not a poor man, his salary was small, and so there was enough for the necessities of life but little left over for luxuries.

Alice was forty when she gave birth to Kathleen, and William forty-five, but the Ferriers had been hoping for another child, and no baby could have been more welcome. Winifred was the eldest, a capable girl, eight years Kathleen’s senior. George was five years older than Kathleen, and already displaying an irresponsibility of temperament which would later cause him, and his family, a great deal of trouble.

William had been the son of a travelling tailor, a calm, steady lad who had taken full advantage of the teacher training college to which his father had scrimped to send him. He studied music theory, becoming an expert on the tonic sol-fa system, and his strong, bass voice made him popular at college concerts. When, aged eighteen, he gained his first position as a teacher, at St Thomas’s School, Blackburn (the town in which he was born), he kept up his musical interests by singing with, and training, the church choir.

If there was artistic temperament in the Ferrier household, however, it stemmed from Alice. Intelligent and passionate, with a keen instinctive love of music, she had had little opportunity in her hard life to express herself, a frustration that manifested itself, at times, in aggressive, resentful outbursts.

Her father had started work in a mill at the age of nine. He married early and had two children, but was widowed by the time Alice was eight. This bereavement turned him morose. He neglected his family, leaving Alice to bring up her six-year-old brother, Jimmy, as best she could.

When Jimmy was twelve, Alice felt she could leave him on his own, so she found herself a job at St Thomas’s School, helping to look after the infants. She loved this, but sadly her pleasure was short-lived. Her father remarried, had three more sons, and his wife, in business, with her own dressmaking shop to run, found the boys too much to cope with, so Alice had to give up her job and stay at home to look after her half-brothers.

While at St Thomas’s, however, Alice, then fourteen, had cast a favourable eye on William. A good-looking youth of nineteen, he seemed to her attractively mature and level-headed. They struck up a friendship which continued and blossomed into a romance even after Alice had left the school. Eventually they became engaged.

Even though William supplemented his salary by teaching at evening classes, his earnings were so small that it was seven years before he and Alice could afford to marry. And even when they did get married, in 1900, Alice and William were obliged to live with William’s widowed mother in a rented house in Blackburn.

Alice’s mother-in-law was bed-ridden, and heavy, and while William was at work, Alice often had to lift her. She was used to hard work, and thought little of this at the time, but the strain took its toll and Alice attributed the stillbirth of her first son to this, and also the health problems she later developed.

With the arrival of Winifred and George there was considerable financial hardship. And when, in 1910, the rent of the house was raised from 5/9d per week to 6/3d the situation worsened significantly. William might have paid the new rent and meekly put up with things but not Alice. Determined to do the best possible for her children, she searched the area until she found a cheaper house, and there the family lived until she discovered she was pregnant again. With three children the new place would be too cramped, so larger accommodation was needed. It was Alice, again, who found No 1, Bank Terrace, Higher Walton, a small village situated between the thriving towns of Preston and Blackburn, where Kathleen was born.

By the time Kathleen was eighteen months old, the Ferriers had moved yet again, now to 57, Lynwood Road, Blackburn. The reason for this was Alice’s desire to provide her children with the fullest possible lives. It was not only that the schools were better in Blackburn—the town itself, with its parish church, concert hall and numerous shops, offered far more than Higher Walton. And there was the Corporation Park just a few minutes away from Lynwood Road, where the children could run about safely in the open air. The move was made possible because, at Alice’s instigation, William had applied for, and been awarded the headmastership of St Paul’s School, Blackburn, a position which brought a rise in salary.

Kathleen showed an early interest in music. While still a toddler, when her cousin Trixie came for a visit, Kathleen ran to the piano to play for her, but could only manage one finger tunes. She burst into tears, crying, ‘I want to play, but I can’t play properly!’1 Clearly her passionate desire for perfection had early beginnings.

Perhaps those tears also showed an obstinately determined will. She certainly demonstrated this a few years later, when some local boys tried to disrupt a little sale she and a friend had organised in aid of Dr Barnado’s homes. She had been on the gate, collecting the halfpenny entrance fee, when the boys tried to get in without paying. Kathleen was big for her age, and loved a rough and tumble, and she was not going to allow the boys to upset her plans. She chased them far up the road.

In later years, Kathleen would tell people that she had been a plain child. She even convinced Sir John Barbirolli of this by delving into a box of photographs and producing several snaps of herself as an infant. She also told the critic, Neville Cardus, that her mother had looked hard at her one day and commented, ‘I’m ill off about our Kath, she’s going to be so plain.’2

Certainly the photographs tell us she was not conventionally pretty. Curly hair was then the fashion for children, and Kathleen’s hair was straight. Plumpness was considered attractive and Kathleen was gawky. But if she was not beautiful, she was highly intelligent. Spurred by an elder brother and sister, she was able to read before she started school. She learned to recite poetry from memory and loved doing this for visitors, with no trace of self-consciousness. She was a born performer.

She started at St Silas’s Elementary School when she was five, but did not stay more than a few months, as Alice had heard that its standards of hygiene were low. Ever concerned for her children, she withdrew Kathleen and placed her in Crosshill, the preparatory department of Blackburn High School. Crosshill was fee-charging, and in order to meet these fees Alice had to get a job.

In fact, she found two jobs. The first, in the daytime, was with the Army Recruiting Office, and the second took up four evenings a week, when she helped out William at a local play centre.

Actually, she was delighted to have the excuse to go out to work: housework bored her stiff, and she thoroughly enjoyed her jobs, particularly the one at the recruiting office. Her jobs were so time-consuming, however, that she felt obliged to spend all her non-employed hours looking after the family, and thus she was unable to join any of the nearby music societies. She resented this, as she loved music, regarding it almost as sacred. Such was her respect for it that when eventually the family acquired a wireless set no one was allowed to talk while music was being broadcast; it was either listened to or switched off.

Kathleen continued to amuse herself at the piano, and progressed from playing one finger tunes to using two fingers and a thumb. She played for a family friend who was so impressed that she bought her a copy of Smallwood’s Piano Tutor. With the aid of this, and help from Alice, Kathleen learned to read music. Although Alice had not had music lessons, she had taught herself, and played the piano quite well. William, also, was always ready to help and advise her.

Winifred was already having piano lessons, and George was singing in a choir, so now something had to be done for Kathleen. Convinced that the child had pianistic talent, Alice took her to the best available teacher, Miss Frances E. Walker, who taught from her home, 131 Montague Street, in Blackburn.

Miss Walker was a local celebrity and much respected in the district—her pupils had gained a remarkable 500 LRAM and ARCM diplomas. Students came from all over the North-West to study under her keen ear and hawk-like eye.

She has been described by a former pupil, as ‘a dumpy woman with fierce, beady, little eyes’. Her hands were broad, with short fingers, but she could play magnificently, and had been taught by the famous Tobias Matthay. There were two grand pianos crammed into her tiny studio and another, a full-sized concert grand, in her lounge. Dedicated to her art, when Alice arrived with Kathleen in hand, Miss Walker made it plain that she was not prepared to accept a beginner.

But she met her match in Alice, who was not to be put off so easily. Just listen to my daughter, she begged Miss Walker. Miss Walker relented and was agreeably surprised. She was dubious about Kathleen’s unorthodox fingering, but she took her on.

Kathleen’s talent flowered under Miss Walker’s guidance and it soon became evident that Alice’s belief in her daughter had not been misplaced. Winifred has kept a full diary of Kathleen’s career and, according to her files, in 1924, when Kathleen was twelve, she entered the Lytham St Anne’s Festival and came fourth out of forty-three entrants. Her examination pieces included Bach’s Prelude in E Minor and Schafer’s At Eventide, the adjudicator was Dr C.H. Moody. A year later, again at the Lytham St Anne’s Festival, she came second out of a class of twenty-six, her pieces including En Bateau by Debussy, and Julius Harrison was adjudicating.

Kathleen became a familiar sight in Montague Street, the tall girl with the bobbed, flaxen hair, swinging her music case as she walked to Miss Walker’s.

But, while Kathleen was showing such promise, George was proving a difficult child. By the age of fourteen he had grown to the startling height of 6 ft 8 inches and this made him the butt of a lot of teasing from his schoolmates. This seemed to affect his behaviour which, at times, could be disconcertingly uncontrolled and irresponsible.

As well as her music, Kathleen enjoyed school. Doris Ormerod, who taught Kathleen when she was in the Lower Fourth Grade, remembers her as ‘intelligent, worthwhile and what I’d call a real character, but not an academic by any means’. Miss Ormerod also recalls that Kathleen was in the choir, but permission for this was only granted on the understanding that she did not sing out. Her voice was too loud, and there was an unacceptable huskiness about it. ‘We all knew she was musical,’ continued Miss Ormerod, ‘she came from a musical family, but none of us had any idea she was brilliant.’

Kathleen was so good at games that at one time it was hoped she might become a games mistress. Doris Coulthard, a fellow pupil at her school, recalled, ‘She was a real tom-boy, marvellous at netball and all the sports. She walked on her hands beautifully, and did the most perfect cartwheels I’ve ever seen.’

She acted in the school plays, and one of her roles was Bottom in A Midsummer-Night’s Dream. Due to her height, Kathleen was often cast as a man. She was also a clever mimic and her inspiration for much of this came from the many mill girls in the area. She travelled on the trams with them and was intrigued by the way they used their lips, communicating with each other down the length of the vehicles without making a sound. This skill had developed as a response to the noise of the mill machinery, which made normal conversation impossible.

Kathleen was always delighted when her uncle George, William’s brother, came for a visit. He was a jovial man and could easily be persuaded to give a fruity vocal rendition of ‘Lily of Laguna’, to which he did a little dance.

She was also pleased to see her uncle Jim, Alice’s brother. Uncle Jim had spent most of his life on Africa’s Gold Coast—the ‘White Man’s Grave’, as it was then known—and the children loved him to gather them up and tell blood-curdling stories of his encounters with elephants, snakes and the like. And so, often as not, did William, who had had no chance to travel but was fascinated by anything to do with foreign parts.

Alice, however, was horrified one weekend when Uncle Jim drank an entire bottle of whisky, which he had brought with him. Although this may well have been normal practice in Africa it was certainly not the custom in the Ferrier household. But Alice was not distressed so much by the immorality as by the cost: five shillings a bottle.

By now William was a member of the Blackburn St Cecilia Vocal Union, a local choir with a fine reputation, and regularly took part in performances of Messiah and Elijah, so the Ferrier children were brought up in the tradition of English choral music and Kathleen never lost her love for it. In her professional life she would sing the Messiah more than any other work.

In addition to the St Cecilia Vocal Union, William, Winifred and Kathleen later joined Dr Herman Brierly’s Contest Choir. The choir took part in many competitions and on one memorable occasion were invited by the famous Glasgow Orpheus Choir to join them for a festival.

The Hallé Orchestra came regularly to Blackburn to take part in oratorios and to give concerts, and when this happened the whole Ferrier household turned out in force. Kathleen took such delight in these events, and was also showing so much promise as a pianist, that her family felt she ought to go to a music college when she left school. That, however, did not happen and, indirectly, her brother George was to blame.

By now, George was in Canada. He had been in scrapes all his life, so when an emigration scheme was offered under the auspices of the Salvation Army it had seemed sensible for him to take advantage of it. But he remained a continual worry to his parents. They feared he might get into serious trouble in Canada, and that they would then be required to finance his return to England. He was their only son so, no matter how great the sacrifice, they knew that if the call came they must respond—but there was no possibility of saving the cash for his fare home if Kathleen stayed at school, let alone went on to music college. To aggravate the situation, William was about to retire, and the family would then have to manage on a drastically reduced income.

Aware they might be jeopardising Kathleen’s future, the Ferriers still could see no alternative other than to remove her from school. Winifred felt particularly guilty, since she herself had stayed on at school until she was eighteen, and then gone on to teacher training college. But she was powerless to help: although she was now a teacher, she had to repay a loan from the education committee, and this left her only barely enough on which to live. Kathleen was the most composed of all. She accepted the decision without protest.

The same could not be said for Kathleen’s headmistress, Miss Gardner, who voiced her objections to Alice in the strongest terms. Miss Gardner felt that a bright, popular girl like Kathleen should have every chance in life. Alice, who probably privately agreed with her, did not waver in her decision and neither did she mention her concern over George, which was, after all, a private, family matter. She firmly informed the headmistress that she had found Kathleen a job as a trainee at the St John’s Telephone Exchange in Blackburn, at a salary of 8/3d a week.

When Miss Gardner heard that she was even more indignant. But Alice over-rode all objections, pointing out that the job was safe and carried a pension, something not to be scoffed at in those days.

Another, more subtle, change was taking place in Kathleen’s situation, one of which she was probably only vaguely aware. Her uncle Bert noticed it first. He had been on a visit from Birmingham and, when the time came for him to leave, Kathleen and Winifred walked with him to the bus station. After he had said goodbye to Kathleen, he turned to Winifred and remarked, ‘Do you know, I think our Kath’s going to be beautiful.’

At fourteen, she was not only leaving school behind but childhood as well.

Two

Kathleen started work with the Post Office in August 1926, four months after her fourteenth birthday. At that time switchboard telephone operators scribbled down telegrams in pencil on dockets as they were telephoned in. Kathleen’s job was to take these dockets to the typing pool and, later, to collect the typed forms and put them in envelopes. These were then sent by chute to the despatch department two flights below. Sometimes, if she discovered that she had made a mistake, but the chute had already been despatched, she would race downstairs to intercept it before anyone else could get to it. It was her proud boast that she could always beat that chute.

As she gained confidence, so her friendly, out-going personality asserted itself. She introduced her colleagues to her much applauded skill of turning cartwheels and walking on her hands and, a co-worker recalls, was reprimanded when caught by her supervisor, ‘A little decorum, if you please, Miss Ferrier,’ he demanded.

She was soon put in charge of the telegram delivery boys. Roughly the same age as she, these were a rowdy bunch and she later confessed to The Gramophone magazine that they ‘led her an awful dance’.

Kathleen’s spare time was also fully occupied. Being good at tennis, she joined the Exchange team and became an enthusiastic member. True to the Ferrier tradition, she joined a choir, the James Street Congregational Church Choir, and she was also a keen girl guide. A Miss Cope, now living in Sussex, remembers Kathleen taking part in the camp fire sing-songs and lustily joining in the chorus of ‘On Ilkley Moor Bar t’At’.

Sometimes, when she visited her cousins Trixie, Dorothy and Margaret, there would be other sing-songs, but these were much more disciplined—both Alice and William insisted that all the items, even the comedy songs, were sung with a strict regard for musical values.

Shortly after joining the telephone exchange Kathleen took part in the Blackpool Festival. The adjudicator was Granville Hill, music critic for the Manchester Guardian, who reported of her piano playing that ‘the phrasing was delicate and appropriate. The touch was dainty in the staccato passages, but more firmness of outline was necessary.’

Kathleen’s studies with Miss Walker intensified. She had already, in the December of 1925, passed her finals for the Associated Boards of the Royal Academy of Music and the Royal College of Music. She continued to enter competitions and festivals, and when the dates of these conflicted with her work shifts she would pay other girls to stand in for her.

In the June of 1928, when she was sixteen, she again played in the Lytham St Anne’s Festival. Her pieces included Haydn’s Sonata in D Major, No 7 and Little Shepherd by Debussy. The adjudicator, J.F. Dunhill, placed her second out of twenty-seven entrants.

But now a far more exciting prospect appeared on the horizon. That same summer, the Daily Express announced, in a fanfare of publicity, that it was holding a national competition for under seventeen-year-olds, to discover the most promising young British pianist. Run in conjunction with several piano manufacturers, the prizes inevitably included many desirable upright and grand pianos.

To discourage less serious students, an entrance fee of 2/6d was charged. Despite this, a not inconsiderable amount at the time, over 20,000 aspiring pianists entered. These were divided up according to geographical areas, and Kathleen was one of the twenty accepted for her own local area contest, which was to take place at the Memorial Hall, Manchester, on 21 November. The prize was to be an upright Cramer piano, valued at £250, and a chance to take part in the finals at the Wigmore Hall, London, later in the year. Kathleen’s name appeared in a national newspaper for the first time, as she was listed with other hopefuls.

From then on, Miss Walker’s sole aim was for Kathleen to master the test pieces—Morgan’s Le Bal Poudré, Rowley’s The Rambling Sailor and Swinstead’s Serenata. As the day of the contest drew nearer, Miss Walker tried to calm Kathleen’s nerves with the sound advice: ‘If you feel nervous, then so will all the others, and many will be more nervous than you.’ Sensible words, no doubt, but of little comfort to an anxious sixteen-year-old.

So, on 21 November, Kathleen made her first visit to Manchester. The Memorial Hall is just a stone’s throw from the Free Trade Hall, where she was later to have so many triumphs with Sir John Barbirolli and the Hallé. Sadly, of course, no premonition of this filtered through to her. As she sat nervously awaiting her turn in the Memorial Hall’s green room, listening to the other contestants she wondered instead why she had subjected herself to this ordeal, a thought which was increasingly to occur throughout her career.

The result was a near thing, and two of the entrants had to be recalled to repeat their performances three nerve-racking times, which seems unnecessarily brutal. But finally the judges, Dr Harvey Grace and G.O. O’Connor Morris, agreed and the announcement was made that Kathleen was the winner. A fine Cramer upright piano was to be hers, but not before it had stood for several weeks, with an explanatory placard, in the window of a music shop in Blackburn.

Kathleen had not long to rest on her laurels, since the finals were to be held at the Wigmore Hall on 1 December, which gave her just nine days in which to prepare. In London she would be competing against the other sixty-six local area winners and she had a new repertoire to study.

All expenses for the London trip were covered by the Daily Express. This was to be Kathleen’s first visit to the capital, and as she had to stay two nights in London, her mother had hoped to accompany her. Disappointingly, at the last moment Alice fell ill. But Winifred, who was between jobs at school, gladly stepped into the breach.

They took the train south, on 30 November. Winifred recalls Kathleen’s delight in the taxi, courtesy of the Daily Express, which conveyed them from Euston to the Russell Hotel, where they were staying. Both of them, however, were over-awed by the hotel’s magnificence. They thought they must have come to the wrong place: could there be another, more modest, Russell Hotel?

This fear laid to rest, they were shown to their room, where they spent a perplexing few minutes trying to find the light switch for the toilet, which was dark and windowless. By accident they discovered that the light came on automatically when the door was closed. This was a great relief. ‘We laughed until we cried over that,’ recalls Winifred.

Pianos were provided at the hotel, on which the contestants could practise, and Kathleen spent her first evening in London rehearsing.

Next morning the sisters took another taxi, this time to the Wigmore Hall. But now even the novelty of the taxi ride could not cheer up Kathleen. Winifred had never seen her so fraught. She did not relax during the day, and as she stepped onto the platform she was visibly shaking.

Among the contestants were three others of particular interest. One was Frederick Stone, who was to become one of the most distinguished accompanists in the country, and who would later accompany Kathleen at many recitals. The two others were Phyllis Sellick and Cyril Smith who went on to earn fame both as soloists and piano duetists. Phyllis Sellick still recalls the tension of that bleak, December day: ‘It was pretty awful, everyone sitting and awaiting their turn to take the dreadful walk across the stage, to play in front of the judges. I particularly remember the piano we used, it was a Steinway grand. I’d never played on such a wonderful instrument and neither, I am sure, had Kathleen.’

But the piano did not help Kathleen, and she had her first sour taste of failure when her name was not included among the six finalists. Ironically, on that same day the Blackburn Times had published its congratulations on her pass at the Regional Final, and had extended its hopes for her success in London. The piece would make bitter reading when she returned home the following day.

That evening, Kathleen and Winifred went to Drury Lane Theatre, to see Paul Robeson in Showboat. Something in Robeson’s singing, triggered Kathleen’s pent emotions and she burst into tears.

She continued sobbing even after the show, and all the way back on the bus to the Russell Hotel. There she found a telegram awaiting her from Miss Walker: ‘Never mind, love, you did your best.’ This kindness, from her formidable teacher, produced even more tears.

Next morning the taxi, again paid for by the Daily Express, arrived to take them back to Euston Station. Just to add a finishing touch to their humiliation they dropped their battered suitcase noisily down a flight of steps at the hotel. People turned to stare, and they left stiff with embarrassment.