Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

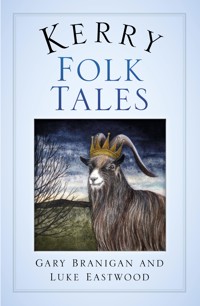

Named after the peoples of Ciarraige who inhabited the ancient territory, Kerry possesses a rich tapestry of history, legend and folklore unparalleled by many others. In this book, authors Gary Branigan and Luke Eastwood narrate a variety of myths and fables that will take you on a journey through Kerry's past. Many of the stories have been handed down by local people from generation to generation, and reveal old customs and beliefs filled with superstition, while others are more modern, showing the continuance of the Irish traditions of the seanachaí and of Irish storytelling.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 271

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2019

The History Press97 St George’s PlaceCheltenhamGL50 3QBwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Gary Branigan and Luke Eastwood, 2019

Illustrations © Elena Danaan, 2019

The right of Gary Branigan and Luke Eastwood to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8744 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Dedicated to my ancestors, the Scannells and Ó Scanaills ofCastleisland and Tralee – Gary

Dedicated to Elena Danaan, who has supported and encouragedall of my writings, including this work – Luke

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 History

2 Legendary Figures and Famous People

3 Local Customs and Old Knowledge

4 Ancient Places and Fabled Spaces

5 Mythical Creatures

6 Quare Happenings and Cautionary Tales

7 Things Religious and Irreligious

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to many people for the kind assistance, guidance and encouragement received, both directly and indirectly, during the compilation of this publication.

Research Facilities at the National Library of Ireland, Kerry County Museum, Dingle Library, National Museum of Ireland (Country Life), Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Office of Public Works, Ordnance Survey Ireland, UCD, and the various local historical, folkloric, and heritage societies have all been invaluable, and thanks go to the wonderful staff who maintain them.

Special mentions deserve to go to Críostóir Mac Cárthaigh of the National Folklore Collection at UCD; to Nicola Guy of The History Press for her endless patience and ongoing assistance during the publication process; and to Elena Danaan: artist, book illustrator, jewellery and fabric designer, and all round good person, who created the absolutely amazing images for the book and to whom we owe a significant debt of gratitude. I would urge everybody to check out her fantastic website at www.elenadanaan.com.

Thanks also to the others, too many to mention here, who assisted in various ways in bringing this book to completion.

I am deeply grateful to Gary Branigan for kindly asking me to assist him in the writing of this book. After almost twenty years of living in County Wexford, I arrived in Dingle as a blow-in with no great ties to the town or County Kerry generally. This was a very unexpected and somewhat daunting opportunity. Despite my fears, it has been a great honour and pleasure to research, uncover and retell these Kerry stories, many of which had fallen into obscurity. I’m also profoundly grateful to Elena Danaan (who illustrated this book) and my friends and family who have supported and encouraged my writing, including this work.

Luke Eastwood

Dingle / Daingean Uí Chúis

January 2019

Without the great help of my co-author Luke Eastwood and illustrator Elena Danaan this book would simply not have been possible, and I extend my sincere thanks to them both. Throughout this challenging journey, Jeannette, Tara, Aoife and Rory have been there, providing an un-ending supply of love, support, encouragement and patience. Words alone cannot express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to them for everything.

Gary Branigan

Dingle / Daingean Uí Chúis

January 2019

INTRODUCTION

So much has been written of the rich indigenous culture extant in our fair isle. From language and customs to dress, music and folklore, the island peoples on the western fringes of Europe are celebrated for their unique way of life.

Within Ireland, many localities have their own idiosyncrasies and home-grown traditions, stories and lore borne out of local history and local circumstance. The kingdom of Kerry is no exception, and this book was created with the intention of sharing and celebrating some of its wealth of local tales and folklore.

Many of these stories are old and have been handed down from generation to generation by local people for local people, while others are more modern, showing the continuance of the Irish traditions of the seanachaí and of Irish storytelling. In reading through the various tales gathered here, the reader will be transported to a time and place long gone, but forever preserved.

Our contribution to this collection of folk tales is in our capacity as storytellers, and in the most part not as academics or historians. Fact and fable, however, are inextricably woven into the fabric of the Irish gene and it is not always possible to separate them, but we have attempted to be as faithful as we can to both.

The medium of telling stories and singing songs is the way the Irish have been able to come to terms with fortune and misfortune alike. It is our hope and belief that anybody will be able to pick up this book and easily enjoy the rich bounty of Kerry’s storytelling tradition.

In selecting tales for inclusion in this publication, we have tried our best to cover from a range generally representative of the county as a whole. Kerry, affectionately known as ‘The Kingdom’ is the fifth largest county on the island and one of the six that form the province of Munster. Named after the peoples of Ciarraige who inhabited this ancient territory, Kerry possesses an unparalleled tapestry of history and folklore, and is central to many of Ireland’s most famous and fantastic myths and legends.

1

HISTORY

BLACK ’47

There have been far too many bad times in Ireland over the millennia. Our history is spattered with an untold number of stories of grief and suffering.

One such distressing time was nearly 170 years ago, when the vicious blight travelled over on the warm air from Europe and infected the valuable potatoes growing in the ground, causing them to turn black and rot. Such was the scourge of the affliction that there were twice as many people living in Ireland then as there are now, with many departing this life or this land for places better – God be good to them.

The people all over the island had only small plots of land that they rented from the English landlords, and it was from these wee plots that they eked out an existence for themselves and their families. The only thing they had to grow and eat were lumper potatoes and the disease ravaged the lumper the worst of all, leaving people with nothing to eat, practically overnight.

The poor people grew weak and became desperate. Those that survived the first year tried to sow the rotten seed potatoes the following season in the hope of getting a crop, but nothing grew. Many then did the unthinkable and butchered their donkeys and dogs for food in the hope that this blight would pass, but it did not. It wasn’t long before the people started to die of starvation, and the heavy odour of rotten spuds and death settled over the land. People were dying so quickly that they could not make the coffins fast enough, and there are even accounts of people being buried alive.

There is one particular story from Kerry of a man who was being placed into a grave, when he awoke saying, ‘Do not bury me for I am not yet dead.’ The doctor at the graveside, who had lost his mind through sheer exhaustion, said, ‘You are a liar! The doctor knows best!’ and the trench was filled in.

The blight started to take hold in 1845 and grew in strength and severity until the height of 1847, when land and communities were decimated. This year was so bad that it became known as Black ’47. Many people had to leave their houses in the mornings and go around from place to place, looking for something, anything, to eat. Many even ate grass in the hope of getting some sustenance but, of course, it was of little benefit.

When all other options were exhausted, they could apply to be taken into one of the union workhouses in Listowel, Tralee, Dingle, Killarney, Cahersiveen, or Kenmare. These workhouses were set up to look after those who could not look after themselves, and many were horrid but necessary places, full of desperate people in desperate situations. It is true that starvation subsided for many in the workhouses, as they received meager rations of financial aid and yellow meal, but painful deaths continued at the same levels as before from fever, dysentery, and scurvy.

As the famine intensified, workhouses became so overcrowded and underfunded that they began turning people away, resulting in the destitute being left to die at the roadsides and in the ditches.

After burying his sister without a priest, Myles Foley had reached breaking point. His poor sister had been turned away from the local workhouse in Tralee just the day before, and the cold November weather outside proved too much for her already frail body. In equal measures of anger and grief, he strung a black burial shroud across a large stick taken from a tree and painted the words ‘Flag of Distress’ on it. Then he gathered the support of his remaining family and neighbours and they marched in formation to the workhouse, demanding that they be allowed entry or would force their way in. The superintendent and other officers locked the gate and barricaded the door with furniture, but desperation led to the men and women pulling the gate off its hinges and pushing their way in through the door.

As they got inside the main entrance hall, they found that waiting for them were several members of the local constabulary, armed with batons. The guards did not hesitate in beating the poor wretches mercilessly, forcing them back out on to the road. Two of the men had received such a hiding that they died right there. There was no charity for those in need of charity in those times and, sadly, this is just one of many such stories of how philanthropy and oppression went hand in hand at that dark time in our history.

THE BURNING OF BALLYLONGFORD

We shall begin by quoting the famous playwright, novelist and poet, Oscar Wilde, who said: ‘we are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.’ This, for us, demonstrates the feelings of the downtrodden people of Ireland in the early part of the last century.

Not long ago our fair isle celebrated the centenary of the great rebellion, which kick-started a chain of events leading to the independence of the majority of the Irish people.

Kerry is unfortunately noted as being the county to suffer the Rising’s first tragic death, which occurred at Ballykissane Pier just outside the town of Killorglin. Although the rebellion was initially a failure, it caused such a stirring within the Irish people that the flame that ignited inside them has never been quenched.

Following these events, unrest grew fast in Ireland and the British government responded by setting up and dispatching a new battalion of soldiers made up of ex-servicemen and ex-convicts. In reality these soldiers, who came to be known as the Black and Tans, were no more than ruffians and thugs. While the Black and Tans were given a free hand to torment and rampage their way throughout the island at will, young Irishmen and Irishwomen came together and organised themselves into independent militias known as ‘flying columns’. Their aim was to protect their communities against these men and show that they were no longer willing to lie down.

Members of these flying columns ended up on a wanted list, with many left with no option but to leave their families and go on the run. One such man, Eddie Carmody of Sallowglen, was ambushed on the road outside Ballylongford in the winter of 1920. Such was the cruelty of the Tans that they seized the poor unarmed man on the road and shot him several times at close range. He survived, however, and was able to crawl away and stay hidden from them for a while. The Tans frantically looked for him to finish the job and followed the drops of blood left by him on the road. They found him slumped against a ditch and, showing no mercy, dragged him back into the middle of the road and took turns to beat him with rifle butts. Only when they had inflicted enough suffering on the poor man did they finish him off by stabbing him several times.

If this were not enough, they then put his lifeless body on the back of an open cart and displayed it throughout the town, dumping it outside the barracks and leaving it there overnight before allowing his father to collect his body the next day.

This heinous and unnecessary act did not go unnoticed, and the local column made plans and bided their time. In the following spring, in reprisal for the vicious murder of Carmody, two Black and Tan men were shot dead while walking on the Well Road in the town of Ballylongford. This happened in the evening and word of what had happened spread fast throughout the town. Fearing revenge, people stayed indoors and quenched any candles or lanterns in the hope that they would not draw any attention to themselves. When reports of the murders reached the barracks, the remaining officers set upon the local populace with rampant vigour and, with the stench of alcohol on their breaths, set fire to furze bushes and pushed them in through smashed windows and onto the roofs of several cottages and houses in the area.

Any person who met them while they were in their destructive rage did not survive to tell the tale. In typical fashion, the Tans did not concern themselves with the possibility that there could be anybody inside any of the buildings, or indeed with the actual loss of property.

The fires were helped by the fact that the majority of houses were thatched and the weather was unusually dry for that time of the year. The resulting inferno spread quickly across the rooftops, destroying Well Street and Main Street in their entirety, with other areas also affected. Nothing but charred rubble, ashes, and waking nightmares were left behind.

THE ROSE OF TRALEE

The Rose of Tralee festival has become famous all over the world, especially among the Irish diaspora. It was begun by a group of local businessmen in 1957, who resurrected the former Race Week Carnival in an effort to attract more tourism to the town. The festival soon found success, with it being rebranded as the Rose of Tralee in 1959 to capitalise on the well-known nineteenth-century love song of the same name and adopting the festival format that we know today. This decision saw the festival transform from a local gathering into an international event.

At the outset, it was a small affair held on a small scale with a corresponding small budget, and only featuring women from Tralee, but by the early 1960s it was extended to include any women from Kerry, and finally in 1967 to include all women of Irish ancestry.

The song, attributed to poet Edward Mordaunt Spencer and violinist Charles William Glover, was published in the 1850s. It is based on actual historical events experienced by the writer William Mulchinock, and the loss of his love, Mary O’Connor. There is no doubt that their tragic story has left an enduring legacy for the town of Tralee, making it famous the world over.

William Pembroke Mulchinock was born in Tralee around 1820 to wealthy Protestant parents, who were prominent in the wool and linen trade. The family all lived happily at West Villa in nearby Ballyard until the premature deaths of both the father and young brother in close proximity to each other. William, who was reputedly a lay about, dreamer and poet, was particularly devastated by his brother’s death and consoled himself with the usual pastimes of any young man of means. It was on one such outing, at the fair of Ballinasloe, that William met and instantly fell in love with a young lady by the name of Alice Keogh.

On returning to Tralee, he visited his sister Maria and his two young nieces, Anna and Margaret. It was here that he met the children’s maid for the first time, another young lady by the name of Mary O’Connor. She was a great beauty with lustrous long dark hair, captivating eyes, pale skin and remarkable grace. Some might think that William was fickle, but whether he was or was not is a different story. As soon as he laid eyes on Mary, he was immediately lovestruck and forgot all about Alice, his former love.

It is believed that Mary was also born in or around 1820 to her dairymaid mother and shoemaker father. They all lived together in a small house on the aptly named Brogue Maker’s Lane. Her mother was employed by John Mulchinock at his Cloghers House residence, which in turn enabled the young Mary to find work as a kitchen maid at West Villa for the Mulchinocks. Having proven to be intelligent and reliable, Mary was chosen by William’s sister Maria as maid to her two children, which led to her finally meeting William.

On the pretext of visiting his nieces, William took every opportunity to visit Mary. In no time at all, the young couple fell madly in love and despite the disapproval of his family, they began courting and were engaged within a few weeks.

In the very different Ireland of the time, the engagement of an upper-class Anglo-Irish Protestant to a Catholic servant scandalised both families and local society. William’s political leanings concerned many, and his involvement with Young Ireland and the Repeal Association infuriated his loyalist relatives and only served to create enemies for himself. The day following their engagement, William attended a Daniel O’Connell political meeting in Denny Street. There, he unintentionally became embroiled in an altercation, whereby one of his companions instigated a fight with a gentleman by the name of Leggett and seriously wounded him with a sword. Although William intervened to end the conflict, a dragoon captain at the scene held William responsible for the incident and warned him that he would be arrested if the man died.

Shortly afterwards, and while William was spending some time with Mary, his best friend Robert Blennerhassett appeared on the scene with the terrible news that Leggett had died of his wounds, and what should have been a joyous occasion with his new fiancée became one of great sorrow as the two lovers were torn apart.

Blennerhassett insisted that William leave the country as quickly as possible and assisted him in doing so, but before leaving he promised Mary that he would return to her as soon as it was safe to do so.

William eventually settled in India and found himself working as a correspondent on the North-West Frontier. Having conducted himself well, the military authorities in India intervened on his behalf, obtaining Dublin Castle’s permission for him to return home to Ireland in 1849.

William returned to Tralee from his long exile and stayed at the Kings Arms in the Rock, close by where Mary’s family lived. He could not contain his excitement at the thought of their reunion, but just as he stepped outside his lodgings with the intention to visit her, a large funeral procession passed him on the street. Asking his landlord who the poor unfortunate to be buried was, his heart sank in horror when he heard that it was a local unmarried woman named Mary O’Connor, who had died of consumption in the poorhouse at just 29 years old. The poor man was heartbroken and often visited her grave at Clogherbrien cemetery, but without his sweetheart and with Ireland still suffering from the ravages of the famine, there was little incentive for him to stay. He emigrated to America and married, seemingly to his former love Alice Keogh, and they had two children.

William’s collection of ‘Ballads and Songs’ was published in New York in 1851, but this did not feature any mention of his Rose. Although he tried, William Mulchinock never fully recovered from the heartbreaking loss of Mary and after a few years his marriage failed and he returned to Tralee. In his pining for Mary he suffered from depression and alcoholism, and died at his home in Nelson Street in 1864, at 44 years of age.

SMALL BUT MIGHTY: THE VILLAGE OF LIXNAW

Lixnaw, in the north of the county, has been described as an insignificant village in current times, but it was once a thriving and important place – and not to mention the seat of the great Fitzmaurice clan, Barons of Kerry, since the early thirteenth century. During the time of Nicholas, 3rd Baron Kerry, a great number of improvements had been made to the local infrastructure, including the once proud castle, the bridge over the River Brick, and many other contributions to the small town and its environs, which improved the lot of the locals.

Another dominant era in Lixnaw was during the Nine Years’ War, when the town once again became a central place in regional and national affairs, being, as it was, a front in that war. The conflict was instigated by Hugh O’Neill, then fought between Thomas Fitzmaurice, 18th Baron Kerry, and the English forces in a bloody engagement.

It all began in the summer of 1600 when Sir Charles Wilmot, who would later become Viscount Wilmot of Athlone, took command of English forces and stormed the town, much to the great shame and dismay of the Fitzmaurices, who had undermined the castle in preparation for its demolition. Wilmot’s surprise attack enabled him to take the castle, where he quickly established a garrison and made it his centre of operations. Thomas Fitzmaurice should have inherited the Earldom, castle and lands at Lixnaw following the death of his father Patrick in Dublin Castle but these were forfeit as a punishment for their rebellion.

Compounding the Fitzmaurice’s losses, the following month Wilmot gleefully seized another one of their fortresses, Listowel Castle, after a siege of just sixteen days.

Two years later, Fitzmaurice was successful in re-taking his hereditary seat at Lixnaw, expelling the English garrison and leaving his brother Gerald in command. However, it was to be a short-lived success, and in an episode of military ping-pong Wilmot again seized it by swimming his men and horses across the moat and laying siege to the stronghold once more.

Thomas Fitzmaurice, now a fugitive stripped of his lands and any hope of a pardon, evaded further attempts to capture him and fought on in reduced circumstances as the war continued into 1603. Amazingly, after the death of Elizabeth I and the ascension of James I, Thomas succeeded in gaining a pardon from the new king and even obtained the re-grant of the title and lands of his father Patrick.

His descendants continued as Barons of Kerry, becoming Earls of Kerry from 1723 onwards, including William Petty-Fitzmaurice (Earl of Kerry, Marquess of Lansdowne and Earl of Shelburne). William, who grew up in Lixnaw, went on to become prime minister of England in 1782.

Today, nothing at Lixnaw remains of the once illustrious seat of the Kerry earls.

THE SIEGE OF SMERWICK AND THE DOWNFALL OF THE GERALDINES

The Fitzgeralds or Geraldines, Earls of Desmond, and the Butlers, Earls of Ormonde, were two of the most powerful families in Ireland since the Norman invasion; they maintained an intense rivalry down through the centuries that sometimes spilled over into bloody warfare. This bitter feud was effectively ended by the second Desmond rebellion and the subsequent demise of the Geraldine dynasty, but the conclusion did not happen overnight.

Following the first Desmond rebellion, led by James Fitzmaurice Fitzgerald, Fitzmaurice was pardoned but stripped of his lands as punishment. His cousin, the earl, also evicted him from rented land, leaving him effectively in poverty.

In 1575, Fitzmaurice fled to France and began seeking the assistance of Catholic powers in Europe, eventually making his way to Rome to petition Pope Gregory XIII for help. After securing modest assistance, an abortive invasion occurred in 1578 that subsequently led him to return to Rome, seeking further support.

The following year he departed from Spain with a small force of Spanish, Italian and Irish troops, and made his way via the English Channel. He captured two English vessels en route, before arriving at Dingle Harbour in mid July.

On 18 July 1579, the party relocated to Smerwick Harbour at Ard na Caithne, further west on the same peninsula. Here they took advantage of a long disused Iron-Age fort, Dún An Oír (fortress of gold), to establish their garrison, creating new earthworks on the promontory.

With the assistance of papal commissary Nicholas Saunders, Fitzmaurice declared a holy war on Elizabeth I at Dingle with much ceremony, calling upon Ireland to rise up against the heretic queen, who had been excommunicated in 1570.

Fitzmaurice’s forces numbered roughly 100 men, and although two more Spanish galleys arrived soon after with a further 100 troops, it is clear that without raising support his rebellion would have been easily crushed.

Irked by the English authorities undermining Desmond’s power, John of Desmond and his brother James entered the fray on 1 August with the assassination of two English officials in Tralee. Having secured some support from relatives, Fitzmaurice himself was only to play a small role in the war and, having travelled north into the province of Connacht to raise further support, he was killed in a skirmish with the Burkes after his men foolishly stole some horses from his cousin Theobald Burke.

The rebellion was now well underway and leadership was left to John of Desmond, who took over much of south Munster, raising some 2,000 men. In response, the English Lord Deputy brought 600 troops to Limerick, joining forces with Sir Nicholas Malby, Lord President of Connacht, and his army of over a thousand.

Up until now the Earl of Desmond, Gerald Fitzgerald, had stayed out of the conflict and had even given up his son as a hostage to guarantee his loyalty, but strictly on the condition that his lands not be attacked. After the plundering of Geraldine territory and the demand that the earl hand over his castle, the situation changed. Gerald refused to leave Askeaton Castle and, despite assurances from the English, he was declared a traitor, which left him with no choice but to enter the war on the side of the rebels. In November of that year he sacked Youghal in County Cork, escalating the conflict to all-out war and imploring Irish lords to defend Ireland and its Catholic faith.

In July 1580, following the rising of the O’Byrnes in Wicklow, the English sent a new army of 6,000 men under the new Lord Deputy, Baron Arthur Grey. After an initial humiliating defeat at Glenmalure, Grey marched his men south into Munster to support the English forces there, unleashing a campaign of terror that would be long remembered.

Pope Gregory, whose hand was stoking the fires of war across Europe, intervened once again in Ireland. Having failed to convince Philip II of Spain, who had his own difficulties with the Dutch and Ottomans, to invade Ireland, the Pope secured ships to transport a force of around 700 Spanish, Italian and Basque troops under the command of Sebastiano di San Giuseppe.

The Papal army arrived in Smerwick Harbour on 10 September 1580, joining the small force at Dún An Oír before heading inland to join the Earl of Desmond, John Desmond and Lord Baltinglass. However, the English had somehow gained knowledge of the invasion and, with a force of around 4,000 men, Lord Grey and the Earl of Ormonde marched to cut them off.

Meanwhile, a naval blockade provided by Sir Richard Bingham prevented them leaving by sea to join the Irish rebels elsewhere. Trapped in the Dingle peninsula, Giuseppe was forced to retreat to Smerwick and make what they could of the defenses at Dún An Oír.

In October, Grey took his forces as far as Dingle and waited for supplies and eight cannons to arrive by sea with Admiral Winter at Smerwick. With the Papal forces trapped by the English on one side, the sea behind them and Mount Brandon on the other, Grey was in no hurry. When the artillery finally arrived on 5 November, preparations began for the siege, which started two days later.

Hopelessly outnumbered and remorselessly pounded by three warships in the harbour and many artillery pieces on land, the rebels stood little chance in a fort consisting mainly of earthworks. Despite this, they held out for three full days, although Giuseppe rather cowardly tried to bargain with Grey by releasing three local allies to the English. The three men, including a priest (Fr Laurence Moore) were horrifically tortured to no avail, before being used for target practice as the siege continued.

Finally, on 10 November, the defenders could take no more and surrendered to Grey’s terms, which were apparently that they would be spared. However, Grey, in his report to Elizabeth I, maintained that he had demanded an unconditional surrender and ‘that they should render the fort to me and yield their selves to my will for life or death’.

Regardless of what was actually agreed, what happened afterwards is well known. The commander, Giuseppe, along with twelve of his men, emerged from the fort with their flags rolled up and presented themselves to Grey. English troops were sent in to establish that the defenders had indeed laid down their arms and to secure and guard the munitions. Once the fort was secured, the 600 or so troops and the few accompanying women were taken to the place that has since earned the name of the Field of the Cutting (Gort a’ Ghearradh) and executed one by one. The severed heads of the slain were apparently buried in the field where a monument stands today, while their bodies were thrown over the cliffs into the sea below.

After the massacre at Smerwick, the tide turned very much against the Desmonds and their rebellion. The coalition began to fall apart, although the war of attrition dragged on for another two years, with Desmond’s supporters being killed or falling away with the offer of a pardon. In early 1582, John of Desmond was engaged by English troops and killed at the River Avonmore, his head sent to the now infamous Lord Grey.

Grey’s brutality was notorious, but he had still not been successful in defeating the Geraldines. Possibly because of his cruel methods, Grey was recalled to England. The Fitzgerald’s arch enemy the Earl of Ormonde replaced him as Lord Deputy, continuing on with the war that left much of Munster bereft of people, crops and livestock.

By the winter of 1583 the Earl of Desmond stood alone, with only a handful of supporters following him into the Slieve Mish mountains to elude English troops. It was here at Glenagenty that Gerald met his end. Desperate and hungry, he had stolen a few cattle from the Moriarty clan and supposedly mistreated the sister of the clan chief. Owen Moriarty and his men caught up with the earl at a small cabin, where he was killed and beheaded.

In return Moriarty received 1000 pounds of silver, a vast fortune, and Gerald’s head was sent to Elizabeth in London, while his body was strung from the walls of Cork city for all to see. His title and all the Geraldine lands were confiscated by the English crown. Attempts to revive Desmond fortunes and the Earldom soon after were a failure and so the once powerful Geraldine dynasty came to a sad and miserable end.

NEXT PARISH: AMERICA

The breathtakingly beautiful archipelago of Na Blascaodaí, or the Blasket Islands as they have become better known, lie off the west coast of the Dingle Peninsula and form the most western extremity of Ireland. The six islands, namely An Blascaod Mór, Beiginis, Inis na Bró, Inis Mhic Uileáin, Inis Tuaisceart, and An Tiaracht, are so remote that it was said that the next parish over was America.