Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

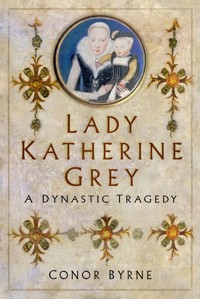

'I have always abhorred to draw in question the title of the crown, so many disputes have been already touching it in the mouths of men . . . so long as I live, I shall be queen of England; when I am dead, they shall succeed that has most right.' – ELIZABETH I When Elizabeth I died in 1603, James VI of Scotland – son of the executed Mary, Queen of Scots – succeeded her as king of England. According to the last will and testament of Henry VIII, however, there was another candidate with 'most right' to succeed Elizabeth: Edward Seymour, son of Lady Katherine Grey. During the early years of Elizabeth's reign, Katherine – sister of the ill-fated Jane – was regarded by many at court as heir presumptive. However, Katherine incurred Elizabeth's lasting displeasure when she secretly married Edward Seymour, earl of Hertford, and bore him two sons. The couple were first imprisoned in the Tower of London, then later separately placed under house arrest, never to see one another again. A commission declared their marriage unlawful and their sons illegitimate. Heartbroken, Katherine died at the age of 27. Katherine was not simply a tragic figure, but a leading candidate to succeed Elizabeth and thus a figure of national and international significance. In Lady Katherine Grey, her dynastic importance is brought to the forefront.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 476

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For my mum

Jacket Illustrations: Portrait miniature of Lady Katherine Seymour, née Grey holding her infant son. (Belvoir Castle, Leicestershire, UK/Bridgeman Images); Floral motifs in an antique fresco. (Orietta Gaspari/iStock)

First published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Conor Byrne, 2023

The right of Conor Byrne to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9488 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

Introduction

1 A Godly Family

2 ‘Tempests of Sedition’

3 Sister to the Queen

4 ‘The Ruin of a Family so Illustrious’

5 At the Court of Mary I

6 ‘The Next Heir to the Throne’

7 A Second Marriage

8 The Queen’s Displeasure

9 ‘An Incomparable Pair’

Bibliography

Notes

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the staff at the British Library, the Bodleian Library, the National Archives, Lambeth Palace Library, Surrey History Centre, Staffordshire Record Office, Gosfield Hall, Ingatestone Hall, Belvoir Castle, the Victoria and Albert Museum and Salisbury Cathedral for assisting with my research enquiries, as well as the various image libraries for their helpfulness. I would additionally like to thank Mark Beynon and the team at The History Press for making this book possible and for being flexible with deadlines. Thanks are also due to Melanie Taylor for her support, advice and encouragement over the years, as well as Rebecca Larson for hosting my article on Katherine Grey on her Tudors Dynasty website. Anthony Wilson accompanied me to Salisbury Cathedral for research and kindly looked over the manuscript. Finally, I would like to thank my family and friends for their support over the years.

List of Illustrations

1. Lady Katherine Grey. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

2. Lady Jane Grey. © National Portrait Gallery

3. Lady Mary Grey. By Kind Permission of the Chequers Trust / © Mark Fiennes Archive / Bridgeman Images

4. Bradgate Park. © Neil Holmes. All rights reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Images

5. Henry VIII. © National Portrait Gallery

6. Mary Tudor, queen of France and duchess of Suffolk. © Ashmolean Museum

7. Edward VI. © National Trust

8. Mary I. © Society of Antiquaries of London, UK / Bridgeman Images

9. Elizabeth I. © National Portrait Gallery

10. Edward Seymour, earl of Hertford. © Sotheby’s

11. Hampton Court Palace. © Author’s collection

12. Tower of London. iStock / © whitelook

13. John Hales, A Declaration of the Succession of the Crowne Imperiall of Ingland (1563). © Lambeth Palace Library

14. Mary, Queen of Scots. © Royal Collection Trust / Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

15. James VI of Scotland and I of England. © National Portrait Gallery

16. Salisbury Cathedral. © Anthony Wilson

17. Tomb of Lady Katherine Grey and Edward Seymour, earl of Hertford, Salisbury Cathedral. © Anthony Wilson

Introduction

According to the last will and testament of Henry VIII, when Elizabeth I died on 24 March 1603, she should have been succeeded by the 41-year-old Edward Seymour, Lord Beauchamp, eldest son of Lady Katherine Grey. Instead, upon Elizabeth’s death James VI of Scotland became the first Stuart king of England. James’ accession to the English throne was not predestined – yet its seeming inevitability has arguably served to marginalise the dynastic significance of Katherine Grey and her heirs. While Katherine herself remains a somewhat obscure figure, her tragic story can be regarded as one of the most significant ‘what ifs’ in British history, and Elizabeth’s determination to exclude Katherine and her heirs from the succession ultimately resulted in the realms of England and Scotland being united under one monarchy in consequence of James’ inheritance of the English throne.

Henry VIII’s decision in the 1540s to reinstate his daughters Mary and Elizabeth in the line of succession created a situation in which the issue of female royal inheritance could, and did, become a matter of dynastic and political significance in the decades ahead. While the king likely did not envisage that his reinstatement of the two women would have practical results, given the hope that his only surviving male heir Edward would produce legitimate sons of his own, female royal inheritance in fact arguably became one of the most pressing issues, if not the most, in the English political sphere upon the death of the childless Edward VI in 1553. It occupied both a crucial and a controversial place in the dynastic politics of Tudor England because, from the death of Edward to the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots in 1587, the leading claimants to the throne were female. Moreover, by barring the descendants of his elder sister – the Scottish line – from the English succession in favour of those of his younger sister – the Suffolk line – Henry set a precedent that was to prove significant, namely that the monarch could ignore existing laws of succession and instead nominate an heir according to their own preferences.

Katherine is popularly remembered as a tragic figure in Tudor history. Her secret marriage to Edward Seymour, earl of Hertford incurred the wrath of Elizabeth I and led to the imprisonment of both Katherine and her husband. Separated from the earl and her elder son, Katherine died in January 1568 at the age of only 27. However, her life was more than a tragic love story. Henry VIII’s last will and testament recognised her as the lawful heir to the throne until such time that Elizabeth married and produced a legitimate heir. Politicians, courtiers and diplomats – both in England and on the Continent – offered support for Katherine’s claim to the throne, whether to safeguard a Protestant monarchy, to protect England’s national interests from the ills of foreign rule or to prevent the succession of a candidate who threatened the interests of another foreign power. In some cases, these goals were intertwined. While James of Scotland ultimately succeeded Elizabeth peacefully in 1603, the English succession was the most controversial and politically charged issue of Elizabeth’s long reign, and its resolution was never guaranteed.

It is possible to regard Katherine’s demise in 1568 as both a personal and a political tragedy. Perhaps best known as the younger sister of the ill-fated Lady Jane Grey, Katherine has not attracted the same degree of scholarly or popular interest as either her sister or her rival for the succession, Mary, Queen of Scots, although she features in all studies of the Elizabethan succession.1 In addition, a number of modern novels have explored her turbulent life.2 This book treats seriously her claim to the throne and identifies her as, arguably, the leading candidate to succeed Elizabeth during the first decade of the queen’s reign, from Elizabeth’s accession in 1558 to Katherine’s untimely and unexpected death ten years later. In doing so, it will draw on a wide range of contemporary sources, including state papers, ambassadors’ dispatches, chronicles and histories, letters and succession tracts, alongside documents pertaining to the investigation into her clandestine marriage.

While the sadness of Katherine’s life and her death at a young age has understandably led historians to identify her as a tragic figure, the issues of her political ambition and importance as the leading claimant to succeed Elizabeth have arguably been marginalised as a result. Katherine’s relationship with Hertford was a love story that ultimately ended in tragedy, but the question of her ambition during the first years of Elizabeth’s reign to be publicly recognised as the queen’s successor deserves to be considered. She was the leading rival to Mary, Queen of Scots and, according to Henry VIII’s preferences, possessed a superior claim to the Scottish queen. Resident ambassadors at court and politicians alike were keenly aware of Katherine’s status as a figure of considerable dynastic and political significance. As one of her earlier biographers noted, Katherine was ‘a princess of the blood and a person of international importance’.3 This importance derived from her royal blood and was strengthened by the recognition of her inheritance rights in Henry VIII’s will and testament, while being intensified by the reality that Elizabeth’s successor was never firmly established, mostly due to the queen’s understandable – if risky – reluctance to name an heir. Prior to her ultimately fatal decision to marry Hertford without securing Elizabeth’s permission, it can be argued that Katherine might have had a strong chance of succeeding the queen. Her secret marriage, instead, led to both her ruin and that of her husband. Having never received the queen’s forgiveness, Katherine’s story tragically concluded with her untimely death on a cold January morning in the Suffolk countryside, far from the royal court in which she had once lived and loved.

1

A Godly Family

Katherine Grey was the second daughter of Henry Grey, marquess of Dorset and later duke of Suffolk, and Frances Brandon. She was born on 25 August 1540, according to tradition at her family home of Bradgate Park in Leicestershire. It is possible, however, that Katherine’s birth actually took place at Dorset House in Westminster.1 The seventeenth-century ecclesiastic and historian Peter Heylyn reported that Katherine was named for Queen Katherine Howard, fifth wife of Henry VIII.2 The royal couple’s wedding had taken place at Oatlands Palace on 28 July, a month before Katherine Grey’s birth. Like her namesake, Katherine Grey would suffer a tragic fate as a result of incurring royal displeasure, although she fortunately escaped the axe.

Katherine’s two sisters, Jane and Mary, were born in 1536 and 1545 respectively.3 The Grey sisters possessed royal blood as great-granddaughters of Henry VII, the first Tudor king. His youngest surviving daughter, Mary – briefly queen consort of France – clandestinely married her brother Henry VIII’s closest friend Charles Brandon, duke of Suffolk, in 1515; their eldest daughter was Frances, who married Henry Grey in the second half of 1533 or early in 1534.4 Frances’ marriage took place only months after the death of her mother on 25 June 1533, who continued, even after her marriage to Brandon, to be referred to as the French queen. The herald and chronicler Charles Wriothesley, for example, recorded her death thus: ‘This yeare, on Midsommer eaven, died the French Queene, sister to the Kinge, and wife to the Duke of Suffolke, and was buried at Sainct Edmondesburie in Suffolke.’5 The royal blood of Frances’ three daughters was to prove a curse for them all. While Jane, famously, was executed as the so-called ‘Nine Days’ Queen’, Katherine and Mary both suffered the consequences of secretly marrying without obtaining the permission of Elizabeth I. At Katherine’s birth in 1540, however, the consequences of her possession of royal blood could not have been anticipated. In fact, Henry VIII had married for the fifth time that summer with the hope of siring sons – a dynastic imperative that the Tudor king could not afford to ignore, given his own history: his accession to the throne in 1509 had occurred only because his elder brother, Arthur, had unexpectedly died seven years earlier, in the spring of 1502. With only one male heir, the 2-year-old Edward, this family history made the need for a ‘spare’ heir all the more pressing.

Katherine spent her childhood in the idyllic setting of Bradgate Park. The seventeenth-century author Thomas Fuller believed that Katherine was born there, ‘in the same place’ where her elder sister Jane was born, although modern historians have determined that Jane was probably born in London.6 Henry Grey had inherited the property in 1530 on the death of his father Thomas, second marquess of Dorset.7 In addition to her Tudor blood, Katherine was descended from Elizabeth Wydeville, consort of the first Yorkist king, Edward IV, by her first marriage to the Lancastrian knight Sir John Grey of Groby. Following Thomas Grey’s death, Henry VIII ordered 1,000 masses to be said for his soul. Dorset’s ‘well-beloved’ wife Margaret was appointed her husband’s chief executor, and the marquess stipulated that his son and heir Henry was to remain under the care of his schoolmaster Richard Broke.8 Henry held a position in the household of the king’s illegitimate son Henry Fitzroy, duke of Richmond and Somerset. Prior to his father’s death, it was suggested that Henry would marry Katherine Fitzalan, daughter of the earl of Arundel, but when he refused to honour the betrothal following his fourteenth birthday, his mother was still required to pay the earl 4,000 marks in annual instalments of 300 marks.9 Henry succeeded his father as marquess of Dorset following the latter’s death in 1530.

In March 1533, Margaret Grey reached an arrangement with Charles Brandon, duke of Suffolk, concerning the wardship and marriage of her son. The duke paid 2,000 marks for the wardship and £1,000 for the king’s consent for a marriage between his daughter Frances and Henry.10 When the couple married either later that year or early the following year, Frances was 16 years old and Henry either 16 or 17. Frances’ ‘high descent, and the great care of King Henry the Eighth to see her happily and well bestowed in marriage, commended her unto the bed of Henry, Lord Marquess Dorset … a man of known nobility and of large revenues’.11 In 1538, when he was 21 years old, the marquess was described as ‘young, lusty, and poor, of great possessions, but which are not in his hands, many friends of great power, with little or no experience, well learned and a great wit’.12 Another contemporary believed Dorset to be ‘an illustrious and widely loved nobleman of ancient lineage, but lacking in circumspection’.13 His relations with his mother were fractious: in 1538, Dorset reached his majority and was in a position to take control of his estates and move to Bradgate Park (thus forcing his mother to leave the residence), leading Margaret to write to the king’s chief minister Thomas Cromwell seeking his intercession, for she was ‘a poor widow unkindly treated by her son the Marquis, and not suffered to have her own stuff out of her own house’.14

Frances Brandon’s reputation has traditionally been negative. She has long been condemned for both her alleged dynastic ambition and physical cruelty to her daughters. Alison Weir, for example, asserted that Frances was possessed of ‘aggressive ambition’. She ‘was forceful, determined to have her own way, and greedy for power and riches. She ruled her husband and daughters tyrannically, and in the case of the latter, often cruelly, and was utterly insensitive to the feelings of others.’15 It is suggested that both she and her husband beat their daughters.16 In her biography of Lady Jane Grey, Alison Plowden commented that Frances was ‘a buxom, hard-riding woman who, as she grew older, began to bear an unnerving resemblance to her late uncle Henry [VIII]’.17 She also alleged that Frances and Henry did not show affection to their daughters.18

Plowden’s suggestion that Frances physically resembled her uncle the king is based on the traditional belief that a portrait created by Hans Eworth and held in the National Portrait Gallery, dating to 1559, is a likeness of Frances and her second husband Adrian Stokes. This early identification was problematic, however, given that the ages inscribed above the sitters’ heads (36 and 21) do not correspond with Frances’ and Adrian’s known ages in 1559. The portrait was re-identified in the late twentieth century as a likeness of Mary Fiennes, Baroness Dacre and her eldest son from her first marriage, Gregory. The female sitter bears a marked similarity to the sitter in an earlier portrait of the baroness painted by Eworth, both of which feature a woman with the same distinctive ring on the fourth finger of her left hand. Elizabeth Honig commented that, in such images, the man was usually positioned on the left and the woman on the right. The double portrait emphasises ‘her son’s superficiality and almost feminine youthfulness’, in contrast to the ‘masculine consolidation of self which power, cemented by experience, has given Mary’.19 The baroness is presented in ‘her first husband’s place as the keeper of the Dacre dynasty’,20 following his execution in 1541. The misidentification of the sitter in this portrait as Katherine Grey’s mother served only to worsen her already poor reputation, in giving rise to the suggestion that her alleged physical resemblance to her uncle Henry VIII reflected the tyrannical and cruel nature that Frances shared with the king. She has also been condemned for her allegedly hasty second marriage to Stokes following the execution of her first husband in 1554.

As Leanda de Lisle noted, Frances’ reputation as a child abuser is based on The Schoolmaster, written by the future Elizabeth I’s tutor Roger Ascham, which stated that Jane had characterised her parents as ‘sharp’ and ‘severe’ when he visited her at Bradgate in 1550.21 According to Ascham, Jane proclaimed that:

One of the greatest benefits that ever God gave me, is, that he sent me so sharp and severe parents, and so gentle a schoolmaster. For when I am in presence either of father or mother; whether I speak, keep silence, sit, stand, or go, eat, drink, be merry, or sad, be sewing, playing, dancing, or doing any thing else; I must do it, as it were, in such weight, measure, and number, even so perfectly, as God made the world; or else I am so sharply taunted, so cruelly threatened, yea presently sometimes with pinches, nips, and bobs, and other ways (which I will not name for the honour I bear them) so without measure misordered, that I think myself in hell, till time come that I must go to Mr Elmer; who teacheth me so gently, so pleasantly, with such fair allurements to learning, that I think all the time nothing whiles I am with him. And when I am called from him, I fall on weeping, because whatsoever I do else but learning, is full of grief, trouble, fear, and whole misliking unto me. And thus my book hath been so much my pleasure, and bringeth daily to me more pleasure and more, that in respect of it, all other pleasures, in very deed, be but trifles and troubles unto me.22

On one level, Jane’s treatment at the hands of her parents, as apparently described to Ascham, could be interpreted as a conventional aspect of the society in which she lived. The twentieth-century historian Lawrence Stone, for example, famously suggested that the early modern family was a ‘low-keyed, unemotional, authoritarian institution’, while relations between parents and children were remote in an age in which ‘individuals ... found it very difficult to establish close emotional ties to any other person’.23 Stone’s interpretation of early modern family relations, however, has been increasingly questioned based on his problematic use of evidence, while a wide range of material illuminates the ‘close emotional ties’ that did exist in early modern England.

One difficulty with Ascham’s account is that it was only published after the deaths of both Jane and her parents. Other evidence for the cruelty of Frances and her husband is the suggestion that when Jane initially refused to marry Guildford Dudley in the spring of 1553, she was punished by being beaten until she capitulated. However, the Suffolk gentleman Robert Wingfield, who wrote an account of Mary Tudor’s successful coup in 1553 entitled the Vita Mariae Angliae Reginae, offered an alternative narrative. Wingfield reported that Henry and Frances were reluctant to agree to a marriage between Jane and Guildford because of their dynastic ambitions for their eldest daughter, having long hoped that she would wed Edward VI prior to his untimely death. Their agreement to the Dudley marriage was based, according to Wingfield, on Henry Grey’s fear of Guildford’s father, the duke of Northumberland, who ‘seemed to be like Phoenix in his companionship with the king and second in authority to none’ in the spring of 1553.24 Finally, the most convincing interpretation of Ascham’s account is that, in recording Jane’s alleged words, the scholar sought to prove an educational moral, namely that children learn better with a kind teacher.25

Evidence dating from Jane’s lifetime presents a more balanced view of her relations with her parents. John Aylmer wrote to Henry Bullinger on 29 May 1551, noting that Dorset ‘loves her [Jane] as a daughter’.26 There is no evidence that any of the Grey sisters were physically abused by their parents, and Jane’s younger sisters seem to have had a good relationship with Frances.27 The suggestion that Henry and Frances ‘were incapable of affection, or of differentiating, emotionally, between their girls’28 is not supported by contemporary evidence. While the suggestion that the marquess and marchioness of Dorset treated their daughters cruelly in pursuit of their dynastic goals can, therefore, be dismissed, it is nonetheless apparent that Katherine and her sisters would have grown up with a strong sense of their royal lineage. At Katherine’s birth in 1540, both of Henry VIII’s daughters were illegitimate and there was, as yet, no indication that the king would name them in the line of succession should his only male heir die without having produced heirs of his body. Rumours circulated at court during Katherine Howard’s brief queenship about the possibility that the queen was with child, all of which proved to be false. During the early 1540s, therefore, the Grey sisters’ place in the Tudor succession may not have attracted a great deal of attention, but the illegitimacy of Henry’s two daughters, even when they were reinstated in the succession by Act of Parliament in 1544, created an ambiguous dynastic situation, as would become apparent during the reign of Edward VI.

By virtue of her status as the king’s niece, Frances and her husband were visible figures at court during the final years of Henry VIII’s reign. The marquess of Dorset undertook a number of important political and military activities during the last years of the reign, but there is little evidence to suggest that the king had a particularly high opinion of his abilities. Indeed, a later account claimed that Dorset ‘had few commendable qualities which might produce any high opinion of his parts and merit’.29 He undertook ceremonial duties at court and commissions of the peace, for example in Somerset, Wiltshire and Devon, but did not participate in the wars with Scotland during the 1540s or in the subsequent negotiations for peace.30 He was also not appointed to the Order of the Garter during Henry’s reign, only gaining that honour in Edward VI’s reign, a period in which he acquired greater political significance through, for example, serving on the Privy Council. Dorset was known for his fervent reformist beliefs and, instead of viewing the Grey sisters’ childhoods as unhappy and characterised by physical and emotional abuse, it would be more fruitful to consider the religious climate of the 1540s in which Katherine and her sisters spent their childhoods for insights into the household in which they grew up.

As a result of Henry VIII’s determination to annul his marriage to Katherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn, the king’s chief minister Thomas Cromwell had overseen the break with Rome and the resulting religious reforms that led to the establishment of the Church of England, including the aggressively efficient dissolution of the monasteries during the 1530s. Both the crown and the nobility, irrespective of individual religious beliefs, benefited financially from the dissolution of the monasteries. The suppression of papal authority went hand in hand with attempts to extirpate traditional Catholic practices and symbols, including the use of images, statues and rood screens, all of which were denounced by reformers as idolatrous. These measures met with active resistance, most notably with the outbreak of the rebellion known as the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536. Some historians have argued that it was Henry, rather than Cromwell or other prominent figures like Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, who was the driving force behind the unprecedented religious changes in England.31

The king’s attitude to the Reformation remains contentious. It is generally agreed, nonetheless, that he became increasingly opposed to the radical direction in which the religious reforms of the late 1530s were heading. The Act of Six Articles (1539) upheld traditional Catholic practices and beliefs, including transubstantiation and clerical celibacy. The execution of Cromwell the following year was perceived as another victory for conservatives at court. However, both reformers and conservatives alike were harshly treated if their religious activities were perceived as threatening to royal supremacy. In 1540, the French ambassador offered his opinion on the king’s recent decision to execute both papists and reformers for their religious practices:

[I] t is difficult to have a people entirely opposed to new errors which does not hold with the ancient authority of the Church and of the Holy See, or, on the other hand, hating the Pope, which does not share some opinions with the Germans. Yet the Government will not have either the one or the other, but insists on their keeping what is commanded, which is so often altered that it is difficult to understand what it is.32

The execution of Katherine Howard in 1542 has traditionally been interpreted as a setback for the conservatives at court, most notably the queen’s uncle Thomas, duke of Norfolk, but other developments, including the publication of the King’s Book in 1543, defended traditional religious beliefs and practices. Henry VIII’s sixth and final marriage to Katherine Parr was welcomed by the reformers in view of the queen’s active support for the reformist cause, most notably in publishing her own work, although rumours of heresy in her household placed her queenship, if not her life, in danger, if the later account of the martyrologist John Foxe is to be believed. Certainly, the brutal torture and execution of Anne Askew for heresy in 1546 was a clear demonstration of the king’s determination to exterminate heresy from the kingdom. However, Henry’s decision to provide for a regency council ultimately ended the reign on a triumphant note for reformers at court, given that the conservatives who would have been placed on it to assist in governing during his son’s minority – including Norfolk and Bishop Stephen Gardiner – fell foul of the king. As a result, reformers such as the king’s brother-in-law Edward Seymour, earl of Hertford, found themselves in positions of strength at the death of Henry VIII in 1547.

In this climate of religious toing and froing during the final decade of the reign, Katherine Grey’s father was firmly committed to the reformist cause. His eldest daughter Jane was celebrated both during her lifetime and posthumously for her devout Protestant beliefs, and the shaping of her faith was in large part a result of the climate in which she grew to maturity. In 1550, the reformer John of Ulm noted that Dorset ‘has exerted himself up to the present day with the greatest zeal and labour courageously to propagate the gospel of Christ. He is the thunderbolt and terror of the papists, that is, a fierce and terrible adversary.’33 It is plausible that the marquess’ religious beliefs became increasingly radical during Edward VI’s reign, given the unprecedented scale of reform within the kingdom in those years. The Edwardian Reformation was marked by widespread iconoclasm as a result of the commitment to the destruction of traditional religion and establishment of a godly commonwealth. These measures were encouraged by the celebration of the young king as the biblical King Josiah, whom reformers praised for having brought his people back to God’s word. The king’s reformist beliefs had been actively shaped by the tutors selected for him by Henry VIII, including Richard Cox and John Cheke. Foxe celebrated Edward as a ‘godly imp’.

Dorset’s piety influenced his selection of tutors for his three daughters. These included the Cambridge scholar John Aylmer and Michelangelo Florio; the latter instructed Jane in Italian. All three of Dorset’s daughters studied Latin and Greek, while Jane also learned Hebrew. The family’s chaplains John Haddon, Thomas Harding and John Willock – all of whom held reformist beliefs – were also involved in the girls’ education.34 The books owned by the youngest daughter Mary later in life, moreover, demonstrate her knowledge of French and Italian.35 Modern historians have long acknowledged Jane’s formidable intellect, and some have unfairly contrasted her scholarly abilities with those of her younger sister Katherine. Hester Chapman, for example, claimed that both Katherine and Mary were brought up in the shadow of their sister, due to Jane’s ‘superior intellect and stronger personality’, and suggested that Katherine may have felt the need to compete with, even outstrip, her sister later in life.36 No evidence supports Chapman’s assertion, and while the marquess and marchioness of Dorset may understandably have focused their ambitions on Jane, as their eldest daughter, it is clear that Katherine and Mary were not neglected in the education that was provided to them. The assumption that Katherine was foolish or intellectually limited is usually the result of comparisons with her gifted elder sister, while knowledge of Katherine’s politically unwise decision to marry the earl of Hertford secretly has also informed assumptions about her intelligence. An unverifiable historical tradition claims that she was the most attractive of the three Grey sisters.37 Certainly, her portraits – which will be discussed later – testify to her physical charms. By contrast, the youngest Grey daughter, Mary, suffered from a physical deformity that was described as leaving her ‘crooked backed’.

The correspondence of the Swiss reformer Henry Bullinger has been viewed as evidence that the household at Bradgate ‘clearly took over as the principal aristocratic nursery of reform in England’ during the 1550s.38 Aylmer, who tutored the Grey daughters, informed Bullinger that their family ‘is both well disposed to good learning, and sincerely favourable to religion’.39 Jane’s correspondence with leading European reformers is well known. The marquess and marchioness were clearly desirous of raising their daughters to be godly maidens, to behave virtuously with a desire to honour both their royal lineage and the noble house of Grey. They would have been expected to possess the virtues of ‘chastitie, shamefastnes, and temperaunce’ associated with women, as noted by the Cambridge scholar John Cheke.40 While Dorset’s committed reformist beliefs influenced the nature of education that his three daughters received, it is highly likely that his wife Frances also played an important role in this sphere. In the spring of 1551, in a letter to Sir Nicholas Throckmorton, Sir Richard Morysine referred to Frances’ ‘heats’ in commenting that ‘so goodly a wit waiteth upon so forward a will’.41 Indeed, she ‘was of greater spirit’ than her husband.42 Such characterisations of the marchioness serve as evidence of her forceful, spirited personality. In addition to their formal education, Frances would have ensured that her three daughters were instructed in the conventional pursuits deemed essential for young women of the nobility and gentry in sixteenth-century England, including sewing, embroidery, dancing, music and singing. Katherine and her sisters would also have acquired the necessary skills to manage a household. Evidence from later in her life suggests that Katherine was fond of animals, a passion that may well have begun in childhood.

With royal blood in their veins, Katherine and her sisters could anticipate prestigious marriages once they had reached maturity. The marquess and marchioness of Dorset nurtured ambitions that Jane would marry Edward VI, the only surviving child of Henry VIII by his third wife Jane Seymour. It has been suggested that Jane was carefully educated in view of her parents’ ambition for her ‘to be the pious Queen of a Godly King, the rulers of a new Jerusalem that Dorset intended to help build’.43 Following the death of Henry VIII, however, Edward Seymour, Lord Protector and duke of Somerset – uncle of the young Edward VI – regarded Jane as a possible bride for his son and heir, Lord Hertford. In view of Katherine’s young age, it is understandable why the issue of her marriage was not raised prior to 1553. Her step-grandmother Katherine Brandon, duchess of Suffolk, conveyed her disapproval of children being married at too young an age to William Cecil, then secretary of the duke of Somerset: ‘I cannot tell what unkindness one of us might show the other than to bring our children into so miserable a state as not to choose by their own liking.’44 In the last years of the fifteenth century, Henry VII’s consort Elizabeth of York and his mother Margaret Beaufort had voiced similar opposition to the intended marriage of the royal couple’s eldest daughter Margaret with James IV of Scotland, in view of her youth, and had insisted that the wedding take place at a later date. There was, as yet, no urgent need to arrange a marriage for Katherine.

Little evidence survives of Katherine’s childhood. Growing up in the Leicestershire countryside, she could have had no awareness of the developments at court, as Henry VIII’s reign drew to an end, that were to have a profound bearing on her future and that of her sisters. Despite infamously marrying six times, as Henry increasingly contemplated mortality he was left with the realisation that he had only one male heir – still a child – to guarantee the survival of the Tudor dynasty. The 1544 Succession Act had reinstated the king’s illegitimate daughters Mary and Elizabeth in the line of succession, but Henry’s decision not to restore their legitimacy ultimately left them in ambiguous positions that would become especially problematic during the following reign. The 1536 Succession Act empowered the king with the right to appoint his successor by his will, and this right was confirmed in the 1544 Act.45 On 30 December 1546, the king implemented a final revision to his last will and testament, which was signed with a dry stamp. John Edwards has noted that one provision in the 1544 Succession Act later proved crucial: the right of the sovereign to amend the order of succession further in a subsequent will and testament, for ‘this was a move of great constitutional significance since it meant that the succession was now in effect to be determined not by legitimacy of birth or by hereditary right, but by the will of the sovereign acting under parliamentary statute’.46 A number of questions would arise during the 1560s’ succession controversy of Elizabeth I’s reign about the validity, or otherwise, of Henry VIII’s will, but for now it is important to note that the king’s will affected Katherine and her sisters in that it named them in the line of succession.

Upon Henry’s death, he would be succeeded by his only son, Edward, then aged 9 years old. The will appointed sixteen executors to sit on a regency council to govern during Edward’s minority, headed by the prince’s maternal uncle Edward Seymour, earl of Hertford. Although neither Mary (daughter of Katherine of Aragon) nor Elizabeth (daughter of Anne Boleyn) were recognised by their father in his last will and testament as being legitimate, he nonetheless decreed that they could in turn succeed their brother Edward if the latter died without siring heirs.47 The king also stipulated that both Mary and Elizabeth would lose their places in the succession if they married without the consent of the councillors in office during Edward’s minority; thus their place in the succession was conditional.48 If, however, Mary and Elizabeth both also died childless, then the crown ‘shall holly remayn and cum to the Heires of the Body of the Lady Fraunces [Brandon] our Niepce, eldest Doughter to our late Suster the French Quene [Mary Tudor] laufully begotten’, and then to ‘the Heyres of the Body of the Lady Elyanore [Brandon] our Niepce, second Doughter to our sayd late Sister the French Quene laufully begotten’.49

It remains unknown why the king overlooked his niece Frances in favour of her offspring. It is possible that she was excluded because of Henry’s low opinion of Frances’ husband, which also seems to have been the case regarding the list of councillors nominated by the king to govern during his son’s minority – Dorset was absent.50 According to contemporary hereditary and dynastic succession customs, Mary, Queen of Scots – granddaughter of the king’s elder sister Margaret – should have had precedence over Lady Jane Grey and her sisters, but Henry VIII ignored existing beliefs about primogeniture in royal succession.51 Historians have puzzled over Henry’s reasons for excluding the descendants of his elder sister – the Scottish line – from the line of succession in favour of those of his younger sister, but undoubtedly the king had no reason to believe that his three children would in turn die childless, thus creating a succession controversy at the heart of English political culture during the second half of the sixteenth century. Given that Edward inherited the throne at the age of 9 years old and was not, contrary to popular belief, constantly plagued by ill health, there was every reason to believe that the young king would marry and sire heirs of his own with which to ensure the continuation of the Tudor dynasty. That was not, in fact, the case, and his final, fatal illness in 1553 would change the lives of Katherine Grey and her sisters, Jane and Mary, forever.

2

‘Tempests of Sedition’

Upon Henry VIII’s death on 28 January 1547 at Whitehall Palace, his 9-year-old son Edward became king of England. Katherine’s father acted as chief mourner at the late king’s funeral, a role granted him as a male kinsman of the new king.1 He and the other twelve mourners ‘prepared themselves in their mourning habits, as hoods, mantles, gowns, and al other apparels, according to their degrees; and were in good order and readiness at the Court, to give their attendance when they should be called’.2 On 3 February, the marquess assembled with the other mourners ‘in the pallet chamber, in their mourning apparel’ and proceeded to the hearse, Dorset’s ‘train born after him’.3 The marquess made an offering ‘with the rest following after him in order two and two’, after a requiem mass had taken place and ‘the chappel singing and saying the ceremonies therto appertaining, in most solempn and goodly wise, to the offertory’.4

On 13 February, three solemn masses were sung, after which Dorset, as ‘chief mourner, accompanied with al the rest of the mourners, offered for them al’.5 The mourners and prelates subsequently withdrew to the Presence Chamber to dinner.6 The following day, the marquess rode ‘next to the chariot … alone, his horse trapped al in black velvet’, followed by the twelve mourners, as the funeral procession made its way through Charing Cross, Braintree and Syon to St George’s Chapel, Windsor, where the king had directed that he would be buried beside the mother of his son and heir, Jane Seymour.7 The burial itself took place on 16 February. Dorset also officiated as Constable of England at the coronation of Edward VI four days later and rode in front of the king during the coronation procession, carrying an upturned drawn sword.8

At the coronation service, Archbishop Cranmer hailed the new king as a second Josiah, exhorting further reformation of the English Church and calling for the ‘tyranny’ of the Pope to be expunged from the realm. Edward’s reign has been described as a period of ‘evangelical revolution’, and both the duke of Somerset and the earl of Warwick – the respective leaders during the king’s minority – actively worked to create ‘King Josiah’s purified Church’.9 Church property continued to be confiscated and the chantries were dissolved. The 1549 Book of Common Prayer, which was criticised by reformers for not being radical enough, was replaced by that of 1552, which removed many of the traditional sacraments and religious observances. Edward’s reign was characterised by widespread iconoclasm as part of the concerted effort to suppress idolatry and superstition. Reformed doctrines, such as justification by faith alone, were made official.10 For Catholics, the new king’s accession meant that ‘the observance of Catholic piety was put to flight and abolished, as far as the public government could prevail, and heresy and schism brought in place’.11

As the religious revolution of Edward’s reign progressed, Katherine Grey and her sisters grew to maturity within the godly atmosphere at Bradgate. However, from Katherine’s perspective, perhaps the most significant development in the spring of 1547 was not Henry VIII’s death but the placing of her elder sister in the household of the Lord Admiral, Thomas Seymour, maternal uncle of Edward VI and brother of the Lord Protector, the duke of Somerset. Sir John Harington, friend and servant of the Lord Admiral, was sent to Dorset House shortly after Edward’s accession to suggest that Jane reside in Seymour’s household, with the promise that he would arrange Jane’s marriage to the king. Harington described Jane as:

as handsom a Lady as eny in England, and that she might be Wife to eny Prince in Chrestendom, and that, if the King’s Majestie, when he came to Age, wold mary within the Realme, it was as lykely he wold be there, as in eny other Place, and that he wold with it.12

Given that the Lord Admiral’s brother, the duke of Somerset, hoped to marry Jane to his son Edward, earl of Hertford, it is possible that in securing Jane’s wardship, Seymour sought to thwart his elder brother’s ambitions.13 William Parr, marquess of Northampton, later testified that Seymour had confided to him ‘that ther wolde be moch ado for my Lady Jane, the Lord Marques Dorsett’s Doughter; and that mi Lord Protector and my Lady Somerset wolde do what they colde to obtayne hyr of my sayd Lord Marques for my Lord of Hertforde; butt he sayd, they should not prevayle therin, for my sayd Lord Marques had gyven hyr hollye to hym, upon certeine Covenants that wer betwene them two’.14 The Lord Admiral offered Dorset a loan of £2,000 in return for permitting Jane to join Seymour’s household as his ward.15

It has been suggested that Dorset initially agreed to be the Lord Admiral’s friend and ally as a result of the marquess’ ill treatment at the hands of the Lord Protector, namely by ennobling Parr as marquess of Northampton (formerly, Dorset had been the only marquess in the realm) and excluding Dorset from the Privy Council.16 The marquess later claimed that, at Seymour Place, the Lord Admiral ‘used unto me at more length the like persuasions as had been made by Harrington for the having of my daughter, wherein he showed himself so desirous and earnest, and made me such fair promises’.17 Dorset subsequently agreed to send his daughter to the Lord Admiral’s household once Seymour had promised £2,000 in return for her wardship and a future marriage with the king.18

Jane’s departure from Bradgate marked a formative change in her life. There is no way of knowing whether Katherine enjoyed a close relationship with Jane, although historians have usually contrasted Jane’s pious and scholarly nature with Katherine’s alleged frivolity. Some, including Chapman, have asserted that Katherine was jealous of Jane.19 There is no evidence for this and unfortunately the nature of their relationship remains uncertain, although Katherine would certainly have been aware of her parents’ ambitions for Jane, namely their desire for her to marry Edward VI. Katherine’s relations with her younger sister Mary are similarly obscure.

In view of his duty to produce an heir to ensure the continuation of the Tudor dynasty, the subject of the young king’s marriage attracted considerable interest in diplomatic circles during his brief reign. While the marquess and marchioness of Dorset hoped that he would marry their eldest daughter, and accordingly ensured that Jane received an education suitable for a godly queen consort, foreign ambassadors speculated about the possibility of Edward marrying into one of the European royal houses, primarily those of France and Scotland. In February 1547, only a month into Edward’s reign, it was claimed that King François I of France, who had formerly favoured a marriage between Edward and Mary, Queen of Scots as a means of securing the restitution to him of Boulogne, might ‘now attempt to renew these negotiations’.20 The imperial diplomat Jean de St Mauris also reported the French king’s willingness to encourage a marriage between Edward and Mary as a means ‘for the recovery of Boulogne’ and ‘on the condition that, if he brought about the said marriage, he should be set free of his obligation to pay the two millions in gold, by which he thinks he would be doing for England far more than the value of the said two millions’.21 Towards the end of that year, St Mauris noted that the Lord Protector had sent a delegation to Berwick to speak with the Scottish envoys about a marriage between Edward and Mary as a way of obtaining ‘an understanding between the English and Scots’ and to come to terms with France, Scotland’s long-standing ally.22

Following her departure, Jane spent her time alternately at Seymour Place and at Chelsea, the residence of the dowager queen, Katherine Parr. She seems to have become part of Katherine’s entourage. The dowager queen secretly married Seymour sometime that spring, only months after Henry VIII’s death, although the exact date is unknown. It was only in July, for example, that the imperial ambassador François van der Delft informed the Holy Roman Emperor that Katherine:

was married a few days since to the Lord Admiral, the brother of the Protector, and still causes herself to be served ceremoniously as Queen, which it appears is the custom here. Nevertheless when she went lately to dine at the house of her new husband she was not served with the royal state, from which it is presumed that she will eventually live according to her new condition.23

The previous month, he had reported that ‘a marriage is being arranged between the Queen Dowager and the Lord Admiral brother of the Protector’.24 A fictionalised account of Seymour’s relationship with Katherine claimed that the Lord Protector actually encouraged their courtship as a means of putting his younger brother ‘in a great position’, and accordingly the duke and Katherine discussed and arranged her marriage to the Lord Admiral, ‘which was performed by the Archbishop of Canterbury, and was known all over London the next day’.25

Irrespective of the circumstances of her marriage, Katherine’s devout Protestantism surely exerted a strong influence on Jane, helping to shape the young girl’s renowned piety. The martyrologist John Foxe noted that Katherine possessed ‘virtues of the mind’ as well as ‘very rare gifts of nature, as singular beauty, favour, and comely personage’.26 As queen, she had been ‘very much given to the reading and study of the holy Scriptures’.27 Jane would undoubtedly have flourished under the care of the scholarly and pious dowager queen, who had published a number of religious works since 1544 including Prayers or Meditations (1545), later translated by her stepdaughter Elizabeth into Latin, French and Italian as a New Year’s gift for Henry VIII. The more radical The Lamentation of a Sinner was published after Henry’s death. The eldest Grey daughter would have spent time during this period with Elizabeth, also in residence in Katherine’s household, although it does not appear that the two were close, despite their shared love of learning.

It is almost certain that Jane learned of the scandal involving Seymour and Elizabeth, which culminated in the dowager queen expelling her stepdaughter from her household in an attempt to protect both her reputation and that of the Lord Admiral.28 Seymour had visited the teenaged Elizabeth in her bedchamber at Seymour Place when she stayed at that residence with the dowager queen, coming up ‘every Mornyng in his Nyght-Gown, barelegged in his Slippers, where he found commonly the Lady Elizabeth up at hir Boke’.29 Such behaviour led Elizabeth’s governess Kat Astley to warn Seymour that ‘it was an unsemly Sight to come so bare leggid to a Maydens Chambre; with which he was angry, but he left it’.30 At Chelsea, the Lord Admiral:

wold come many Mornyngs into the said Lady Elizabeth’s Chamber, before she were redy, and sometyme before she did rise. And if she were up, he wold bid hir good Morrow, and ax how she did, and strike hir upon the Bak or on the Buttocks famylearly, and so go forth through his Lodgings; and sometyme go through to the Maydens, and play with them, and so go forth: And if she were in hir Bed, he wold put open the Curteyns, and bid hir good Morrow, and make as though he would come at hir: And she wold go further in the Bed, so that he could not come at hir.31

Elizabeth’s cofferer Thomas Parry believed that the Lord Admiral:

loved her but to well, and hadd so done a good while; and that the Quene was jelowse on hir and him, in so moche that, one Tyme the Quene, suspecting the often Accesse of the Admirall to the Lady Elizabeth’s Grace, cam sodenly upon them, wher they were all alone, (he having her in his Armes:) wherfore the Quene fell out, bothe with the Lord Admirall, and with her Grace also.32

Nowadays, Seymour’s relations with Elizabeth are interpreted as predatory, tantamount to child abuse, and the potentially treasonous nature of the affair caused sufficient scandal to prompt the Privy Council to order an investigation into the goings on.

Jane accompanied the dowager queen, then pregnant, to Sudeley Castle in the summer of 1548 following the departure of Elizabeth from Katherine’s household. In August, Dorset visited Jane there and informed her that, among other news, her sister Katherine was studying Greek with the family chaplain Thomas Harding.33 Unfortunately, there is no record of whether Katherine enjoyed these lessons, but it is usually assumed that she lacked her elder sister’s scholarly nature. Katherine Parr died on 5 September at the age of 36 from childbed fever, only six days after giving birth to a daughter, Mary. Jane officiated as chief mourner at the dowager queen’s funeral, which has been described as the first Protestant funeral held in English. The dowager queen’s death resulted in Jane returning to Bradgate, but it is ridiculous to assert that her parents regarded her ‘as a failure’ and were disappointed as a result of her unexpected return to their care.34

In fact, the marquess and marchioness were eager for Jane to return to them. Dorset was ‘fully determined, that his Doughter the Lady Jane shuld no more com to remaine with the Lord Admirall’, but the Lord Admiral did not take no for an answer, being ‘so earnest … in Persuasione’, namely regarding his promise to arrange Jane’s marriage to Edward VI.35 The courtier Sir William Sharington, a friend of Seymour, likewise persuaded Frances ‘to let the sayd Lady Jane come to my Lord Admirall’.36 Seymour also confessed to Dorset his antipathy to the Lord Protector and declared that ‘he wold have the King to have Thonor of his own Things; for, sayd he, of his Yeres he is wise and lerned’.37 On 17 September, less than two weeks after his wife’s death, Seymour wrote to Dorset:

After my most hartye commend unto your good Lordship. Whereby my last Lettres unto the same, wrytten in a Tyme when partelye with the Quene’s Highnes Deathe, I was so amased, that I had smale regard eyther to my self or to my doings; and partelye then thinking that my great Losse must presently have constrayned me to have broken upp and dissolved my hole House, I offred unto your Lordeship to sende my Lady Jane unto you, whensoever you wolde sende for her, as to him whome I thought wolde be most tendre on hir: Forasmuche as sithens being bothe better advised of my self, and having more depelye disgested wherunto my Power wolde extend; I fynde indede that with God’s helpe, I shall right well be hable to contynewe my House together, without dyminisheng any greate parte therof. And therfore putting my hole Affyance and Trust in God have begonne of newe to establish my Houshold, where shall remayne not oonelye the Gentlewomen of the Quene’s Hieghnes Privey Chamber, but allso the Maids which wayted at larg, and other Women being about her Grace in her lief Tyme, with a hundred and twenty Gentlemen and Yeomen, contynualle abeyding in House together; saving that now presentlye certaine of the Mayds and Gentlemen have desyred to have Licence for a Moneth, or such a thing, to see theyr Frends; and then immedyately returne hither again. And therfore doubting, least your Lordship might think any unkyndness, that I shoulde by my saide Lettres take occasion to rydd me of your Doughter so soon after the Quenes Deathe: For the Prof both of my hartye Affection towards youe, and good Will towards hir, I mynd now to keape her, untill I shall next speak with your Lordshipp; whiche should have been within these thre or four Dayes, if it had not been that I must repayr unto the Corte, aswell to help certane of the Quenes pore Servants, with soome of the Things now fallen by her Death, as allso for my owne Affayrs; oneles I shalbe advertysed from your Lordship of your expresse Mynd to the contrarye. My Ladye, my Mother, shall and wooll, I doubte not, be as deare unto hir, as though she weare hir owne Doughter. And for my owne Parte, I shall contynewe her haulf Father and more; and all that are in my House shall be as diligent about her, as your self wolde wyshe accordinglye.38

The dowager queen’s death meant that it would have been inappropriate for Jane to reside in the widowed Lord Admiral’s household. Recognising this difficulty, Seymour sought to put her parents’ minds at ease by explaining that his mother, Margery, Lady Seymour, would assume responsibility for Jane’s care. In October, then about 12 years old, Jane wrote to Seymour thanking him for the ‘goodnes’ he had shown her:

My dutye to youre lordeshippe in most humble wyse rememberd withe no lisse thankes for the gentylle letters which I receavyed from you Thynkynge my selfe so muche bounde to your lordshippe for youre greate goodnes towardes me from tyme to tyme that I cannenot by anye meanes be able to recompence the least parte thereof: I purposed to wryght a few rude lines unto youre lordshippe rather as a token to shewe howe muche worthyer I thynke youre lordshippes goodnes then to gyve worthye thankes for the same thes my letters shall be to testyfe unto you that lyke as you have becom towardes me a louynge and kynd father so I shall be alwayes most redye to obey your momysons and good instructions as becomethe one uppon whom you have heaped so manye benyfytes. and thus fearynge leste I shoulde trouble youre lordshippe to muche I moste humblye take my leave of your good lordshyppe

your humble servant durynge

my life jane graye39

Neither of Jane’s parents were convinced of the merits of returning Jane to the Lord Admiral’s household, instead believing that she should stay at home under her mother’s supervision. Dorset wrote to Seymour from Bradgate thanking him for his ‘most frendly Affection towards me’ and Jane in offering ‘thabode of my Doughter at your Lordeshypes House’, but explained that:

Nevertheless considering the State of my Doughter and hyr tendre Yeres, wherin she shall hardlie rule hyr sylfe as yet without a Guide, lest she shuld for lacke of a Bridle, tak to moche the Head, and conceave such Opinion of hyr sylfe, that all such good behauior as she heretofore hath learned, by the Quenes and your most holsom Instructions, shuld either altogither be quenched in hyr, or at the leste moche diminishid, I shall in most hartie wise require your Lordeshippe to committ hyr to the Governance of hyr Mother; by whom for the Feare and Duetie she owithe hyr, she shall most easilye be rulid and framid towards Vertue, which I wishe above all Thinges to be most plentifull in hyr.40

Dorset sought ‘in thes hyr yonge Yeres, wherin she now standeth, either to make or marre (as the common saing ys) thadressing of hyr Mynd to Humilytye, Sobrenes, and Obedience’.41 In alluding to his desire for Jane to be guided by her mother in learning virtuous behaviour, Dorset voiced the contemporary belief that ‘the archetypal good woman was a godly matron’ in a culture in which medical understanding of the female body supported religious beliefs about women’s inferiority.42