15,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

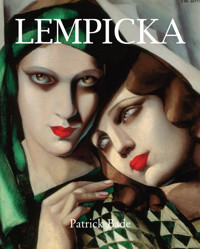

The smoothly metallic portraits, nudes and still lifes of Tamara de Lempicka encapsulate the spirit of Art Deco and the Jazz Age, and reflect the elegant and hedonistic life-style of a wealthy, glamorous and privileged elite in Paris between the two World Wars. Combining a formidable classical technique with elements borrowed from Cubism, Lempicka’s art represented the ultimate in fashionable modernity while looking back for inspiration to such master portraitists as Ingres and Bronzino. This book celebrates the sleek and streamlined beauty of her best work in the 1920s and 30s. It traces the extraordinary life story of this talented and glamorous woman from turn of the century Poland and Tsarist Russia, through to her glorious years in Paris and the long years of decline and neglect in America, until her triumphant rediscovery in the 1970s when her portraits gained iconic status and world-wide popularity.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 172

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Text: Patrick Bade

Layout: Baseline Co Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

Nam Minh Long, 4th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Image-Barwww.image-bar.com

© de Lempicka Estate / Artists Rights Society, New York, USA / ADAGP

© Denis Estate / Artists Rights Society, New York, USA / ADAGP

© Lepape Estate / Artists Rights Society, New York, USA / ADAGP.

© Dix Estate / Artists Rights Society, New York, USA / VG Bild-Kunst.

© Pierre et Gilles. Galerie Jérôme de Noirmont, Paris

© O’Keeffe Estate / Artists Rights Society, New York USA

© Lotte Lasterstein.

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright in the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-744-5

Patrick Bade

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

EARLY LIFE

ART DECO

TURNING POINT

MASTERWORKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Tamara de Lempicka in evening dress, c. 1929.

Black and white photograph on paper, 22.3x12cm.

INTRODUCTION

Tamara de Lempicka created some of the most iconic images of the twentieth century. Her portraits and nudes of the years 1925-1933 grace the dust jackets of more books than the work of any other artist of her time. Publishers understand that in reproduction, these pictures have an extraordinary power to catch the eye and kindle the interest of the public. In recent years, the originals of the images have fetched record sums at Christie’s and Sotheby’s. Beyond the purchasing power of most museums, these paintings have been eagerly collected by film and pop stars.

In May 2004, the Royal Academy of Arts in London staged a major show of de Lempicka’s work just one year after she had figured prominently in another big exhibition of Art Deco at the Victoria and Albert museum. The public flocked to the show despite a critical reaction of unprecedented hostility towards an artist of such established reputation and market value.

In language of moral condemnation hardly used since Hitler’s denunciations of modern art at the Nuremberg rallies and the Nazi-sponsored exhibition of Degenerate Art, the art critic of the Sunday Times, Waldemar Januszczak, fulminated “I had assumed her to be a mannered and shallow peddler of Art Deco banalities. But I was wrong about that. Lempicka was something much worse. She was a successful force for aesthetic decay, a melodramatic corrupter of a great style, a pusher of empty values, a degenerate clown and an essentially worthless artist whose pictures, to our great shame, we have somehow contrived to make absurdly expensive.”

According to Januszczak, de Lempicka did not arrive in Paris in 1919 as an innocent refugee from the Russian Revolution but on a sinister mission, intending “an assault on human decency and the artistic standards of her time.” One cannot help wondering what it was about de Lempicka’s art that should bring down upon it such hysterical vituperation. There is a clue perhaps in his waspish observation “Luther Vandross collects her, apparently. Madonna. Streisand. That type.”

The hostility is perhaps more politically than aesthetically motivated and what really got under the skin of certain critics was the glamorous life style of Tamara’s collectors as well as of her sitters.

EARLY LIFE

Portrait of Baroness Renata Treves, 1925.

Oil on canvas, 100x70cm,

Barry Friedman Ltd., New York.

Tamara de Lempicka’s origins and her early life are shrouded in mystery. Our knowledge of her background is dependent upon some highly unreliable fragments of autobiography, and upon the accounts given by her daughter Baroness Kizette de Lempicka-Foxhall to de Lempicka’s American biographer Charles Phillips. De Lempicka was a fabulist and a self mythologiser of the first order, capable of deceiving her daughter and even herself. Much of her story as told by her daughter has the ring of a romantic novel or a movie script and may not be much more authentic.

Both the place and the date of de Lempicka’s birth vary in different accounts. There is nothing more significant in the changing birth dates than the vanity of a beautiful woman (in Tamara’s time female opera singers with the official title of Kammersängerin had the legal right in the Austro-Hungarian Empire to change the date of their birth by up to five years).

According to some, de Lempicka changed her birth place from Moscow to Warsaw which could be more significant. There has been speculation that de Lempicka was of Jewish origin on her father’s side and that the deception over her place of birth resulted from an attempt to cover this up. Certainly the ability to reinvent oneself time and again in new locations, manifested by de Lempicka throughout her life, was a survival mechanism developed by many Jews of her generation. The prescience of the danger of Nazi Germany in a woman not usually politically minded and her desire to leave Europe in 1939 might also suggest that she was part Jewish.

The official version was that Tamara Gurwik-Gorska was born in 1898 in Warsaw into a wealthy and upper-class Polish family. Following three partitions in the late eighteenth century, the larger part of Poland including Warsaw was absorbed into the Russian Empire. The rising tide of nationalism in the nineteenth century brought successive revolts against Russian rule and increasingly harsh attempts to Russify the Poles and to repress Polish identity. There is little to suggest that Tamara ever identified with the cultural and political aspirations of the Polish people. On the contrary, she seems to have identified with the ruling classes of the Tzarist regime that oppressed Poland. It is telling that in 1918 when she escaped from Bolshevist Russia she chose exile in Paris along with thousands of Russian aristocrats, rather than live in the newly liberated and independent Poland.

The family of her mother, Malvina Decler, was wealthy enough to spend the “season” in St. Petersburg and to travel to fashionable spas throughout Europe. It was on one such trip that Malvina Decler met her future husband Boris Gorski. Little is known about him except that he was a lawyer working for a French firm. For whatever reason Boris Gorski was not someone that Tamara chose to highlight in her accounts of her early life.

From what Tamara herself later said, she seems to have enjoyed a happy childhood with her older brother Stanczyk and her younger sister Adrienne. The wilfulness of her temperament, apparent from an early age, was indulged rather than tamed. The commissioning of a portrait of Tamara at the age of twelve turned into an important and revelatory event. “My mother decided to have my portrait done by a famous woman who worked in pastels. I had to sit still for hours at a time... more... it was a torture. Later I would torture others who sat for me. When she finished, I did not like the result, it was not... precise. The lines, they were not fournies, not clean. It was not like me. I decided I could do better. I did not know the technique. I had never painted, but this was unimportant. My sister was two years younger. I obtained the paint. I forced her to sit. I painted and painted until at last, I had a result. It was imparfait but more like my sister than the famous artist’s was like me.”

Peasant Girl Praying, c. 1937.

Oil on canvas, 25x15cm, Private Collection.

The Polish Girl, 1933. Oil on panel,

35x27cm, Private Collection.

If Tamara’s vocation was born from this incident as she suggests, it was encouraged further the following year when her grandmother took her on a trip to Italy. According to Tamara, she and her grandmother colluded to persuade the family that the trip was necessary for health reasons. The young girl feigned illness and her grandmother was eager to accompany Tamara to the warmer climes of Rome, Florence and Monte Carlo as a cover for her passion for gambling. The elderly Polish lady and her startlingly beautiful granddaughter must have looked as picturesquely exotic as the Polish family observed by Aschenbach in Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice. Visits to museums in Venice, Florence and Rome lead to a life long passion for Italian Renaissance art that informed de Lempicka’s finest work in the 1920s and 30s. A torn and crumpled photograph of Tamara taken in Monte Carlo shows her as a typical young girl de bonne famille of the period before the First World War. Her lovingly combed hair cascades with Pre-Raphaelite abundance over her shoulders and almost down to her waist. She poses playing the children’s game of diabolo but her voluptuous lips and coolly confident gaze belie her thirteen years. It would not be long before she would be ready for the next great adventure of her life – courtship and marriage. Played against the backdrop of the First World War and the death throes of the Russian monarchy, the story as passed down by Tamara and her daughter is, as so often in de Lempicka’s life, worthy of a popular romantic novel or movie.

When Tamara’s mother remarried, the resentful daughter went to stay with her Aunt Stephanie and her wealthy banker husband in St. Petersburg, where she remained trapped by the outbreak of war and the subsequent German occupation of Warsaw. Just before the war when Tamara was still only fifteen, she spotted a handsome young man at the opera surrounded by beautiful and sophisticated women and instantly decided that she had to have him. His name was Tadeusz Lempicki. Though qualified as a lawyer, he was something of a playboy, from a wealthy land-owning family. With her customary boldness and lack of inhibitions, the young girl flouted convention by approaching Tadeusz and making an elaborate curtsey. Tamara had the opportunity to reinforce the impression she had made on Tadeusz at their first meeting when later in the year, her uncle gave a costume ball to which Lempicki was invited. In amongst the elegant and sophisticated ladies in the Poiret-inspired fashions of the the day, Tamara appeared as a peasant goose-girl leading a live goose on a string. Barbara Cartland and Georgette Heyer could not have invented a ploy more effective for catching the eye of the handsome hero. In an account that has the ring of truth to it, Tamara admitted that the brokering of her marriage to Tadeusz by her Uncle was less than entirely romantic. The wealthy banker went to the handsome young man about town and said “Listen. I will put my cards on the table. You are a sophisticated man, but you don’t have much fortune. I have a niece, Polish, whom I would like to marry. If you will accept to marry her, I will give her a dowry. Anyway, you know her already.”

Peasant Girl with Pitcher, c. 1937.

Oil on panel, 35x27cm, Private collection.

The Peasant Girl, c. 1937.

Oil on canvas, 40.6x30.5cm,

Lempicka’s Succession.

The Fortune Teller, c. 1922.

Oil on canvas, 73x59.7cm,

Barry Friedman Ltd., New York.

The Gypsy, c. 1923. Oil on canvas,

73x60cm, Private Collection.

By the time the marriage took place in the chapel of the Knights of Malta in the recently re-named Petrograd in 1916, Romanov Russia was on the verge of collapse under the onslaught of the German army and on the point of being engulfed in revolution. The tribulations of the newly married couple after the rise of the Bolsheviks belong not so much to the plot of a novel as of an opera, with Tamara cast in the role of Tosca and Tadeusz as Cavaradossi.

Given the background and life-style of the couple and the reactionary political sympathies and activities of Tadeusz, it was not surprising that he should have been arrested under the new regime. Tamara remembered that she and Tadeusz were making love when the secret police pounded at the door in the middle of the night and hauled Tadeusz off to prison. In her efforts to locate her husband and to arrange for his escape from Russia, Tamara enlisted the help of the Swedish consul who like Scarpia in Puccini’s operatic melodrama, demanded sexual favours. Happily the outcome was different from that of Puccini’s opera and neither party cheated the other. Tamara gave the Swedish consul what he wanted and he honoured his promise not only to aid Tamara’s escape from Russia but also the subsequent release and escape of her husband. Tamara travelled on a false passport via Finland to be re-united with relatives in Copenhagen. It was a route followed by countless Russian aristocrats, artists and intellectuals, often with hardly less colourful adventures than those of Tamara and Tadeusz. The beautiful and extremely voluptuous soprano Maria Kouznetsova, a darling of Imperial Russia, escaped on a Swedish freighter, somewhat improbably disguised as a cabin boy.

Refugees from the Russian Revolution fanned out across the globe, but Paris which had long been a second home to well-healed Russians, became a Mecca for White Russians in the inter-war period. Inevitably, Tamara and Tadeusz were drawn there along with Tamara’s mother and younger sister (her brother was one of the millions of casualties of the war). Unlike so many refugees who arrived there penniless and friendless they could at least rely upon help from Aunt Stefa and her husband, who had managed to retain some of his wealth and to re-establish himself in his former career as a banker.

From the turn of the century the political alliance between Russia and France – aimed at containing the menace of Wilhelmine Germany – encouraged the growth of cultural links between the two countries. The great impresario Sergei Diaghilev took advantage of this political climate to establish himself in Paris. In 1906, Diaghilev organised an exhibition of Russian portraits at the Grand Palais that pioneered a more imaginative presentation of paintings and sculptures. Following this success, he arranged concerts that for the first time presented to the French public the music of such composers as Glazunov, Rachmaninov, Rimsky-Korsakov, Tchaikovsky and Scriabin. Young French musicians, yearning to escape from under the shadow of Wagner, were enchanted by this music that was fresh and new and not German. In 1908 at the Paris Opera, Diaghilev put on the first performances in the West of the greatest of all Russian operas, Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov. Paris was overwhelmed not only by the originality and barbarous splendour of Mussorgsky’s music, but also by the revelation of the interpretative genius of the bass Feodor Chaliapin. Chaliapin had terrified audiences standing on their seats trying to see the ghost in the famous Clock Scene and immediately established a reputation as the greatest singing actor of the age. Misia Sert, perhaps the most influential arbiter of fashionable taste in these years wrote “I left the theatre stirred to the point of realising that something had changed in my life.”

Woman Wearinga Shawl,in Profile, c. 1922.

Oil on canvas, 61x46cm,

Barry Friedman Ltd., New York.

Portrait of a Young Lady in a Blue Dress, 1922.

Oil on canvas, 63x53cm, Barry Friedman Ltd., New York.

The following year, Diaghilev’s efforts climaxed in the presentation to the Parisian public of the Russian ballet. Parisians were dazzled by the dancing and choreographic talents of a company that included such legendary names as Nijinsky, Pavlova, Karsavina and Fokine and by the experience of ballet, not as trivial entertainment but as a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk. Diaghilev and his ballet company continued to dazzle and astonish Paris for the next two decades. Diaghilev had an unparalleled talent for divining and developing the talents of others. Without mentioning the dancers and choreographers who created modern ballet under his aegis, the list of artists and musicians who worked for Diaghilev is a compendium of the greatest talent of the age and includes Stravinsky, Debussy, Ravel, Richard Strauss, Satie, Falla, Resphigi, Prokofiev, Poulenc, Milhaud, Bakst, Goncharova, Larionov, Balla, Picasso, Derain, Braque, Gris, Marie Laurencin, Max Ernst, Miro, Coco Chanel, Utrillo, Rouault, de Chirico, Gabo, Pevsner and Cocteau.

Tamara de Lempicka’s career peaked in the year of Diaghilev’s death, 1929, and the trajectory of his brilliant career has relevance to hers in more ways than one. Diaghilev probably had more to do than anyone with establishing the myth of Russian creativity and exoticism in the arts. In later years when supplies of genuine Russian dancers were cut off by the Russian Revolution and Diaghilev was forced to use British dancers, he maintained their mystique by Russifying their names. So it was that Alice Marks became Alicia Markova, Patrick Healey-Kay mutated into Anton Dolin and Hilda Munnings became Lydia Sokolova after a spell under the unconvincing sobriquet of Hilda Munningsova. By the 1930s the idea that to be Russian was to be glamorous and exotic had permeated popular culture. In the 1937 version of the film A Star is Born, the young girl being groomed for stardom, played by Janet Gaynor is repeatedly asked by an employee of the studio publicity department if she has any Russian ancestry in the hope of creating a more exciting image for her.

Diaghilev’s designers, notably Leon Bakst, played a vital role in developing the Art Deco style with which de Lempicka became associated. In particular Bakst’s designs for the 1910 production of Sheherazade had an extraordinary impact on fashion and interior design. For the next generation, fashionable Parisian hostesses dressed themselves and decorated their salons as though for an oriental orgy. Even in the late 1920s, photographs of Tamara de Lempicka’s bedrooms show decors which, though much pared down from the lushness of Bakst’s designs, make them look as if Nijinsky’s sex slave would not be out of place as an overnight guest.

Paris in the inter-war period was teeming with Russian refugees. It was jokingly said that every second taxi driver in Paris was either a real or pretend Grand Duke. It was a situation that inspired the popular play Tovarich (turned into a Hollywood movie in 1937 starring Charles Boyer and Claudette Colbert) in which two former members of the Russian royal family are forced to earn a living as a butler and ladies’ maid in a wealthy Parisian household. A book on Parisian pleasures with charming Art Deco illustrations, entitled Paris leste commented on Russians partying in Paris, “you could think that there was a pre-war Russian party – that is to say a party where the Russians have money and a post-war Russian party, which is a party where the Russians don’t have money anymore. It’s the same thing! You find the same princes, the same imperial officers and officials in the same clubs. They’re doing the same thing. The only difference is that they used to be the clients and paid, whereas now they are employed by the house.” Tamara herself later claimed to be employing a couple of Russian aristocrats in disguise when she went to live in Hollywood.

Woman with Dove, 1931.

Oil on panel, 37x28cm, Private Collection.

Women Bathing, 1929.

Oil on canvas, 89x99cm, Private Collection.

Group of Four Nudes, c. 1925.

Oil on canvas, 130x81cm,

Private Collection.

Apart from all the dancers, musicians and artists associated with Diaghilev already mentioned, there were numerous creative Russians intermittently or permanently resident in Paris. They included the conductor Sergei Koussevitsky, the harpsichordist Wanda Landowska, the singers Nina Koshetz, Oda Slobodskaya, Natalie Wetchor and the entire Kedroff family, all of whom played an important role in the musical life of Paris and the artists Marc Chagall, Sonia Delaunay-Terk, Natalia Goncharova, Nadia Khodossivitch-Leger, Jacques Lipchitz, Serge Poliakoff, Chaim Soutine, Ossip Zadkine, Romain de Tirtoff (known, as Erté), Chana Orloff, Antoine Pevsner and, after 1933, Naum Gabo and Vassili Kandinsky.