Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

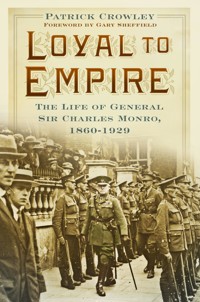

Winston Churchill did not describe General Sir Charles Monro in the most glowing terms. Referring to Monro's brave decision to recommend a withdrawal from the Gallipoli disaster, Churchill said: 'He came, he saw, he capitulated.' Monro was one of a handful of senior officers selected to command a division with the British Expeditionary Force in 1914 and also led a corps on the Western Front as the war progressed. After Gallipoli he was instrumental in supporting the war effort from India as commander-in-chief and was directly involved in the aftermath of the Amritsar massacre by Brigadier General Dyer. His earlier life included distinguished service on the North West Frontier and in South Africa, and he was responsible for dramatically improving tactics within the army. Loyal to Empire brings to life the interesting character of General Monro, perhaps the least well known of all the British First World War commanders, and reassesses the legacy of his important military contributions.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 608

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

General Sir Charles Monro. (Surrey Infantry Museum)

This book is dedicated to the memory of Professor Richard Holmes – the inspiration for this tome – and to the Surrey Infantry Museum at Clandon House, Surrey, which was sadly destroyed by fire in April 2015.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It has taken some time to write and construct this book, as it has been written over a period when I have left the Regular Army after thirty-four years’ service and taken on a new appointment championing the cause of the reserves and cadets in the south-east of England. Main thanks go to my wife, Jane, for being so patient as it was being written, and to Lynne Gammond, who kindly spent time proofreading and making suggestions as it progressed. Special thanks also go to Colonel John Powell, who was working in Gibraltar and researched Monro’s time there for me. In terms of research help, once again Prince Consort’s Library in Aldershot and their head librarian, Tim Ward, have been outstanding and I am extremely grateful to the staff of the Surrey History Centre, Imperial War Museum, Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives at King’s College London, National Army Museum, National Archives, the British Library, Joint Services’ Defence College Library and Sherborne School for their helpfulness. Finally, I am very fortunate that Professor Gary Sheffield, an internationally renowned First World War expert, has done me the honour of writing the foreword.

Patrick Crowley

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Professor Gary Sheffield

Preface

1 The Early Years

2 Service Overseas and Operational Experience

3 South Africa

4 Army Reform

5 Before the War

6 1914

7 Deadlock

8 Gallipoli

9 The 1st Army and the New BEF

10 India

11 The Final Years

12 An Assessment

Appendix I: The Career of General Sir Charles Carmichael Monro, Bart., GCB, GCSI, GCMG

Appendix II: The Honours and Awards of General Sir Charles Carmichael Monro, Bart., GCB, GCSI, GCMG

Bibliography

Glossary

By the Same Author

Copyright

FOREWORD

General Sir Charles Monro is a difficult subject for a biographer. Unlike fellow Great War generals Douglas Haig and Henry Rawlinson, Monro did not leave a voluminous body of papers. The only previous biography is over eighty years old and is sadly inadequate from the point of view of the modern historian. Nor is there much in the way of modern work on Monro: at best, he has a walk-on role in accounts of Gallipoli and Fromelles. John Bourne’s chapter length biographical sketch from 2006 is one of the few exceptions.

Patrick Crowley, in his biography, is making bricks with inadequate amounts of straw in places, but by placing Monro in a wider context reduces this as a problem. The more senior Monro became, the greater his visibility in the sources, and so from the Boer War onwards, Monro the man increasingly comes to the fore, although we often see him through the eyes of others. Patrick Crowley’s achievement is to make Charles Monro a somewhat less shadowy figure, although in the absence of fuller sources, in some respects Monro remains frustratingly elusive.

And yet Monro, as Colonel Crowley demonstrates, was a significant figure. Two roles stand out: his tenure as a senior commander (at divisional, corps and army level) in the First World War; and as commander-in-chief (C-in-C) India. As commander of 2nd Division in the original British Expeditionary Force (BEF), Monro had a key leadership position at a crucial time. Whilst he was not regarded by successive Cs-in-C, French and Haig, as a ‘top tier’ general, Monro still had a hugely responsible and vital role to play. He was fated not to command in the great attritional battles of 1916–17, the Somme, Arras or Passchendaele, nor in the desperate defensive actions of 1918 that proved to be the prelude to the advance to victory from August to November of that year. Thus it is impossible to judge how Charles Monro would have adjusted to the learning process that characterised both the BEF as a whole and its commanders. It is probably unfair to judge him purely on his handling of the Battle of Fromelles in July 1916.

The fact that Monro was selected to become C-in-C India in 1916 is noteworthy, not just because it says something about his reputation as a field commander, but also it is a clear statement of how highly he was regarded as an administrator. This was no sinecure. India was a vital part of the British Empire’s war effort, and it needed a strong and energetic C-in-C. This period saw Monro’s greatest contribution to the British state, which remains remarkably unheralded. Monro had already shown his powers of decision – and moral courage – in taking the decision to abandon the Gallipoli campaign. This was undoubtedly the right call, but it earned him the enmity of Winston Churchill, from whose ever-fertile brain the original scheme had emerged.

There are still many areas of the history of the British Army of the Great War in which much research remains to be done. Surprisingly, high command is one of them. We still know too little about many of the men who commanded major formations. But we now know more about Charles Monro. Undoubtedly, there is more to be done, but Patrick Crowley’s admirable book is an important step in the right direction.

Gary Sheffield

Professor of War Studies, University of Wolverhampton

PREFACE

Kitchener, Haig, French, Robertson, Plumer, Allenby and Smith-Dorrien, along with some other personalities, are relatively well-known commanders, but Charles Monro is probably the least familiar of the senior generals of the First World War; it is about time that this situation was rectified, particularly as the centenary of the conflict is remembered.

However, Monro avoided publicity, was a humble man, left few papers for analysis and had no direct family descendants, so investigating his life is quite a challenge. That is probably why no academic has attempted to study him in detail since General Sir George Barrow’s biography of 1931 and why this book is not a definitive biography – the gauntlet is certainly thrown down to anyone who can achieve the perfect analysis of his life from the reference material available.

Barrow was close to Monro and knew him very well, serving as his chief of staff in the 1st Army during 1916 and in India later. His informative book touches many aspects of his career, particularly Monro’s role in Gallipoli and India, though he avoids any balanced criticism and does not even mention Monro’s role in the controversial Battle of Fromelles on the Western Front. Nor does he provide any defined sources for his comment.

Otherwise, John Bourne has provided an excellent short summary of his career in Beckett & Corvi’s Haig’s Generals, though his experience of regimental duty and his time in India and Gibraltar does not receive great attention. There is also a good summary of Monro’s career by Cassar in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

However, none of these more recent references have gone into such depth as Loyal to Empire. This book goes beyond recent short summaries of his military life and deliberately contextualises certain aspects of his career. Whilst knowledge of his detailed personal contribution to operations in the North-West Frontier of India and in South Africa is scarce, these events helped shape his life and attitude. Therefore, they are worth summarising from the perspective of his regiment, the Queen’s Royal Regiment (West Surrey), and the army formations in which he served.

Monro was instrumental in reshaping musketry tactics before the war at a time of great change within the British Army, yet his role has barely been mentioned in previous histories. He was also one of a few chosen officers to serve as divisional, corps and army commander on the Western Front, was critical in the decision to evacuate the disastrous beaches at Gallipoli and was the senior military commander in India at a particularly crucial and fragile period. This was a loyal and extremely professional officer who was definitely no ‘donkey’ and just ‘got on with the job’.

Patrick Crowley

1

THE EARLY YEARS

Not every future general is born on a ship, but on 15 June 1860 that was Charles Carmichael Monro’s introduction to the world. The Maid of Judah, a wooden sailing ship, was on her way from Melbourne, Australia, to London. On board were his parents, Scotsman Henry Monro, a successful entrepreneur in Australia, but not in good health, and his mother, Catherine (née Power), originally from Clonmult, County Cork, Ireland, and five of his Australian-born siblings, four brothers and one sister.

The Maid of Judah was one of twenty-nine ships that sailed as part of the Aberdeen White Star Line in the period 1842–70: ‘No ships that ever sailed the seas presented a finer appearance than these little flyers … They were always beautifully kept and were easily noticeable amongst other ships for their smartness.’1 The Argus newspaper of Melbourne advertised the journey in the previous March; William C. Mitchell being the captain:

This vessel has earned a first rate reputation, while in the Sydney trade, as one of the celebrated Aberdeen Line for her quick passages, as well as for the excellent condition in which she has always discharged her cargo. She is now alongside the Hobson Bay Railway Pier, and the attention of intending passengers is called to her excellent accommodations, which have been expressly fitted for the Australian trade, her ’tween decks being lofty and well ventilated, and specially adapted for the comfort of second and third class passengers.

The advertisement records the cost of first-class travel as ‘per agreement’ and that the ship ‘carries an experienced surgeon’.2 This was fortunate for Catherine Monro, about to deliver her next son. There are no clues about how advanced her pregnancy was, but she travelled, perhaps knowing that her next child’s arrival was imminent. Charles was born two months out, northbound from Australia, off the Cape of Good Hope. Perhaps the future general’s character was being formed; the combination of an unusual birth, his place in the family and the fact that his father was to die when he was only 9 years old helped to form a very robust character.

Maid of Judah. (Author’s collection)

His biographer and one of his close staff officers on the Western Front, General Sir George Barrow, referring to his parental background commented that he ‘was Scotch when on duty and Irish when off duty’,3 suggesting a certain formality and stiffness in character, tempered by great imagination and the ability to tell fascinating and captivating stories.

The Monros were, and still are, an illustrious and successful family. Charles’ great-uncle, Major General Sir James Carmichael-Smythe, commanded the Royal Engineers at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. One ancestor, Alexander Munro of Bearcrofts, was on the Royalist side at the Battle of Worcester in 1651, entered Parliament and was knighted. His eldest son, George, took over the estate of Auchenbowie, near Stirling, and had helped defeat the Jacobites at Dunkeld in 1689; he also fought at the siege of Namur in 1695. One of Alexander’s other sons, John, was the first of eight generations of extremely successful physicians, helping to establish the Edinburgh University of Medicine. The last of these, another Alexander Monro (‘Tertius’ as he was the third Alexander), was the future general’s grandfather. He became president of the Royal College of Physicians and had twelve children – six boys and six girls.

His fourth son, David, the future general’s uncle, was another member of the family who qualified as a doctor of medicine from Edinburgh, but he was to choose politics in New Zealand as his main career. He was eventually the second Speaker of the House of Assembly and was knighted. One of David’s seven children, Charles John, was credited with introducing rugby to New Zealand in 1870.

Alexander Tertius’ third son, Henry, the future general’s father, went to Australia as a 24-year-old in 1834. His first wife, Jane Christie (née Whittle), whom he may have met on the voyage over, died tragically only one year after their marriage. His ten children were borne by his second wife, Kate. Charles was her sixth child. Though Charles was not to be blessed with children, other branches of the Monro family tree have flourished in various professions over the years and bred two major generals in recent times.4

The family spent a short time in England and Edinburgh, then moved to St Servan in Brittany, France. Charles and his brother, George, were taught French, an extremely useful skill for the future general on the Western Front. The family was then struck by another tragedy, as the boys’ father, Henry, who had headed to Malaga for health reasons, died at the early age of 59. Kate had to cope with the nine children – the three eldest were old enough to be reasonably independent, however the remaining two sons and four daughters were 15 years old and under.5 Charles, now 11, and his slightly older brother, George, were sent to public boarding school at Sherborne in Dorset in 1871, a school their three elder brothers had also attended prior to 1867.6

Charles Monro, aged 7. (Barrow)

Sherborne School

Sherborne School was to be a safe and natural second home for the boys. The school had been founded under the auspices of King Edward VI in 1550 and still has the motto ‘Dieu et mon droit’ (God and my right). It embodied the best of British traditional privileged education and was used to producing future army officers for the Empire. As one of the school’s histories states, ‘The Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny passed by the school without visible memorial; yet twenty Shirburnians served in the former and twenty-four in the latter, and six of them lost their lives.’7

A sense of duty would have been drilled into the boys. This, together with a high level of discipline, were strong characteristics of Charles Monro, as commented on by both Field Marshal Herbert Plumer and George Barrow in later years.8 Barrow quotes that Charles had ‘a smile for everyone’ at school and enjoyed cricket, though he does not seem to have particularly thrived academically. He goes on to say, ‘There was nothing in Charles Monro’s boyhood to mark him as likely to outstrip any of his contemporaries in the race of life.’9 That may be true, but the circumstances of one’s upbringing and experiences at school provide a foundation that affects everyone’s destiny.

Charles and George had arrived at Sherborne at a time when its most legendary reforming headmaster, Hugo Harper, was running the school. He made considerable improvements to the education, both in standards and variety of subjects, whilst expanding the real estate and its size. The curriculum was modernised, the three-term system instigated and science was introduced for the first time. By the time Harper left in 1877, after twenty-seven years in post, there were 248 boarders and eighteen staff and the school was ranked one of the best public schools in the country. When he died in 1895, the School History quoted The Educational Review, describing Harper as ‘the last of the really great headmasters of this century’. One of his wider and longest lasting achievements was helping to establish an independent universities examination board.10 It is doubtful whether the two boys would have appreciated all this, but they would have benefitted.

We do know that Charles and George were pupils in School House, like their three brothers.11 The ‘house’ was very much the close family within the school, as it is today.12 Sherborne now has eight houses, including School House, which was established in 1860, the same year that the railway came to Sherborne town.

Conditions were spartan by today’s standards. School accommodation that was adequate for 300 boys at the time of Charles’ stay ‘was stigmatised as not good enough for 200 in 1901’,13 and the ninety boys of School House shared only four baths. Internal lighting was dim and hot water was scarce. Discipline was tough and often meted out by the senior boys, there were no trained matrons and only limited medical support at hand. One had to be strong to survive these conditions, but the environment was normal for Charles’ strand of society and there are no known references to him being unhappy.

The public school system provided the perfect and typical upbringing for a future senior army officer from the Victorian and Edwardian eras. The emphasis was on producing ‘gentlemen’. As Moore-Bick’s excellent analysis of junior officers on the Western Front states:

Gentlemen were a social elite, identified by precise codes of deportment and conduct. The deferential way in which they were typically treated was balanced by the expectation that they would conform to those standards. Their supposed moral standing and innate authority meant that gentlemen were seen as naturally suited to leadership roles.14

Charles Monro was proud of his connection with Sherborne School and the school magazine proudly tracked his progress through the army. He returned to the annual ‘Commemoration’, or Speech Day, in 1921. The Bishop of Dover preached from the words, ‘Behold I make all things new’ and acknowledged that the post-Great War audience ‘wanted this England – which they loved more than ever because of the sacrifices made for it – to be a better England and the world to be a better world’. General Sir Charles Monro, who was handing out the prizes, was typically more practical after watching physical training and horsemanship skills; the Western Gazette reported:

General Monro impressed the value of physical training, not only for the development of the body, but as a means of inculcating qualities of leadership. The combination of intellectual activity and physical health and energy would, he said, produce that good all-round citizen of which the Empire never stood in greater need than at the present time.15

The emphasis on recruiting potential officers from public schools continued well into the First World War, as the experience was seen to provide a ‘social passport’ and breed appropriate leadership. However, Sherborne School was not one of the main providers of officers to Sandhurst. During the period from 1878 to 1899, most came from Eton, Bedford Grammar School, Harrow, Clifton, Wellington, Winchester, Cheltenham and the United Services School at Westward Ho!16 Also, most of the boys’ fathers were army officers, unlike the Monros. The system of recruiting officers may have suited the period, but does not escape criticisms from later historians. Barnett wrote that as a result of the system ‘the control of the Army remained in the hands of men out of touch with, and out of sympathy with, the social and technical changes of the age’.17

At these schools, paternalistic concern for others was encouraged, but professionalism appears to be less important than contacts and personality; a person’s character was critical. Sherborne School’s move away from just teaching the classics and encouraging sport, to introducing the sciences was relatively radical for the times. There was little radical social change when Charles Monro was at school, but professions were beginning to alter their recruitment policies and open greater opportunities for the middle classes in Britain’s main institutions; the armed forces, Parliament and the Church. For example, the year that Charles began school, 1871, was the same year that the Cardwell Reforms included the abolition of the purchase of army commissions, so even the military system was changing, albeit slowly.

Robbins has analysed the background of 700 senior officers who served on the Western Front at the higher levels of the army in the First World War. Charles Monro, like most of the others, was born in the period 1854–94, with an Anglo-Saxon, Protestant and professional background. Fellow divisional commanders in 1914 were all within six years of Charles Monro’s age and had been schooled at similar institutions to Sherborne School – Eton (Charles Fergusson), Haileybury (Hubert Hamilton) and Marlborough (Henry Wilson), for example. Robbins reinforces the point that ‘the British Army’s elite shared an Establishment and Victorian upbringing, which provided a common social background and elaborate social ties’.18 Old established families like the Monros continued that tradition of service.

It is not known whether the two brothers had much choice but to join the army, however the next step for Charles and his brother, George, was an army ‘crammer’ run by the Reverend G. Brackenbury at Wimbledon. It seems remarkable that, after the high-quality education at Sherborne, a crammer was needed. However, the extra effort was reluctantly required by most candidates for officer training: ‘Detested by universities and colleges, despised by those parents who paid his fees, and scorned often by those who sat under him, the crammer none the less despatched many a famous soldier and empire-builder on the way to immortality.’19 English history, German, French and Latin, mathematics, drawing and geometry were the subjects covered.20

Despite comments by many authors of the amateur nature of Victorian soldiering, this was not the attitude of Captain G. J. Younghusband in 1891: ‘To be a successful soldier requires just as much application and hard work as to be a successful lawyer; and the earlier a young fellow realises the importance of this hard fact, the more likely he is to succeed.’21 He extolled the value of crammers, saying that they gave ‘boys five times as much individual tuition and made them work twice as hard as they had had to at school’.22

The extra individual attention was seen to be worth the effort. Winston Churchill and the future General Sir Hubert Gough went to Captain James ‘Jimmy’, a retired Royal Engineer in Kensington, for their crammer; Lord Kitchener went to Mr George Frost at Greenwich. The future General Sir Ian Hamilton, whom Charles Monro would later succeed at Gallipoli, went to Captain Lendy at Sunbury.23

Charles Monro passed the examinations and entered the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, on 1 September 1878.

Sandhurst

Today, all British Army potential officers are trained at Sandhurst. This was not the case in 1878; future Royal Engineers and Royal Artillery officers attended the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, whilst all other branches had their officers trained at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. Candidates for the latter establishment had to be aged between 17 and 20, younger than today’s recruits.

Captain Younghusband had strong views about which institution provided the best future, though his comment would not be appreciated by modern sappers and gunners:

It is almost as hard for a ‘Sapper’ or a ‘Gunner’ to become a brigadier-general as it is for a camel to go through the eye of a needle. They are both specialists, and a life of specialism is judged to be, rightly or wrongly, an indifferent training for a man who has to command large bodies of men in the future.24

It should be noted that at the time of writing, the Chief of the General Staff is a sapper! Even ‘The Story of Sandhurst’ booklet, issued to the author 100 years later, states, ‘The RMA (Woolwich) generally attracted Gentlemen Cadets slightly lower in the social scale than the RMC (Sandhurst), for the reason that the Artillery and Engineers tended to be less fashionable than the Line (Infantry).’25

One hundred and fifty gentlemen cadets were admitted to Sandhurst in September 1878, including Charles. His brother, George, was on a slightly earlier course.26 Charles joined other cadets, who had arrived in May of the same year and would pass out in December. They ‘were divided into ten divisions of thirty each, with five instructors (as commanders) and five under-officers’.27

Royal Military College, Sandhurst. (Author’s collection)

The course was for one year – eight months of work divided into three terms. The syllabus included, ‘Queen’s Regulations, regimental interior economy, accounts and correspondence, military law, elements of tactics, field fortifications and elements of permanent fortifications, military topography and reconnaissance and riding’.28 Remarkably, ‘musketry was an optional subject until 1892’, however riding was critical.29 Unofficial activities were described as ‘some bullying, some ragging, some drinking, some learning’, and long-term friendships were made.30

Charles Monro’s report is not in the Sandhurst archives, but Barrow records that he did not set the world alight whilst he was there. He was known for unpunctuality and ‘rather below the average of the cadet at his time’.31 He is reported as being a poor horse rider, but Barrow states that he was captain of the cricket team. Evidence for the latter achievement cannot be found, though he was certainly in the team – in the Sandhurst versus Woolwich match of 4 July 1879, C. C. Monro was bowled out by Crampton for a duck!32

The future general passed out very near the bottom of his intake at the 120th position, on 13 August 1879, unlike his future corps commander, Douglas Haig, who was commissioned top of his intake six years later, earning the Anson Memorial Sword.33 Thomas records that the only notable event at Sandhurst in that year was the opening of the new chapel, which still exists today.34 Monro had not peaked early in his military career and this story shows how one should not write people off when they are young.

His age group was to be an important one; as Thomas pointed out, ‘the men of the late seventies and early eighties were the strategists, army or corps commanders, who were to pass the First World War at general headquarters’.35 In the meantime, Charles Monro was commissioned as a second lieutenant into 1st Battalion, the Queen’s (Second) Royal Regiment. It is recorded that the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Francis Hercy, was a friend of the family.36

An interesting year in which to be commissioned, in 1879 Charles would have followed the fortunes of Lieutenant General Chelmsford as he invaded Zululand in that January. There followed the British disaster at Isandlwana on the 22nd, and the unfortunate death in the war of the French Prince Imperial, Louis Napoleon, whilst serving with the Royal Artillery in June. Better news from that front would have arrived in England just before his commissioning, as the incredibly brave action of Rorke’s Drift was fought, earning eleven Victoria Crosses for the army and the decisive battle against the Zulus was won at Ulundi. In the same year, another South African conflict, the ‘Gun War’, was being fought in Basutoland, and in India the Second Naga Hills Expedition was taking place. Meanwhile, the Second Afghan War was being fought and Kabul was occupied in October, followed by the forced resignation of the Emir Mohammed Yakub.

At home, Gilbert & Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore received its debut and Oxford University accepted its first female degree students. Whilst a great deal was going on within the Empire, Second Lieutenant Charles Monro was to start his career inauspiciously, in the garrison town of Colchester.

Regimental Duty

He was joining a proud regiment to which, as a general in much later years, he would be appointed ‘Colonel of the Regiment’. The 1st Battalion had fought during 1838–39 in the First Afghan War, but last had operational experience during 1860 with the war in China, fighting with distinction at Taku Forts. It had only been in Colchester a few months when Charles Monro joined, having just returned from thirteen years in India. The 2nd Battalion was in Bengal, India, but was later to become involved in the Third Burma War. Recruits for both organisations were trained at the brigade depot in Guildford, Surrey.

The regiment had been raised on Putney Heath in 1661, as the Tangiers Regiment in order to garrison Tangier in North Africa, which had passed to the British Crown as part of Catherine of Braganza’s dowry upon marrying King Charles II. It was extremely proud of being England’s senior infantry regiment of the line, taking seniority after the Guards regiments and becoming the 2nd Foot – the 1st Foot were the Royal Scots.37 It had served with distinction around the world and gained a number of battle honours, including Tangier (1662–80), Namur (1695), Afghanistan (1839), South Africa (1851–53), Taku Forts and Pekin (1860).

Regimental colour, the Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment. (Davis)

Its Peninsular War experience took place between 1811 and 1814; it included Vimiera, Corunna, Salamanca, Vittoria, Pyrenees, Nivelle and Toulouse. It had also helped put down the Duke of Monmouth’s rebellion in 1685, the rebellion in Ireland four years later and had served on ship as marines in the naval Battle of the Glorious First of June, in 1794 off Ushant. Charles Monro would have learned the regiment’s two mottoes, Pristinae Virtutis Memor (remembering their gallantry in former days) and Vel Exuviae Triumphans (even the spoiled have their hour of triumph).

The badge of the regiment was the Paschal Lamb. There is no genuine recorded historical reason for this emblem. It is claimed that it was adopted as a Christian symbol in the fight against the Moors at Tangier. Another distinction was the cipher of Queen Catherine – two ‘Cs’ interlaced, with a crown over it. This badge was displayed on the regiment’s unique third colour.38 The colours also displayed the Sphynx, superscribed ‘Egypt’, to commemorate the regiment’s participation in the Egyptian campaign of 1801.

Cap badge, the Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment. (Author’s collection)

It is important to mention these badges and regimental heritage, as it was amongst this tradition and unique ‘tribe’ that Charles Monro gained his initial experience in the army. The regiment and its brother officers and soldiers would help set his standards and professionalism in future years. He had joined a unique ‘band of brothers’ with their own particular esprit de corps within the regimental system.

This system has altered over the years and received both negative and positive comment. At its best, it promotes unit cohesion and motivation in battle. This is brought about by fostering a sense of loyalty and developing an obligation to a corporate identity and reputation. This would have been particularly acute in Charles Monro’s battalion after its long service together overseas, its fine history and traditions. This sense of belonging, sharing common experiences, continuity and regional connections providing a focus for recruiting, traditions and esprit de corps are acknowledged attributes for a regiment as much today as they were then. However, there was, and still is, the danger that people’s potential and initiative are not capitalised within such a small insular organisation, which can be inflexible and generate inefficient rivalry between units.39

As a young subaltern, Charles Monro was about to see significant changes to this system as a result of the Cardwell-Childers reforms to the British Army, which were implemented from 1870 to 1881. These were described as ‘the first in the century to amount to a root and branch reorganisation of the British Army’.40 Some changes had already occurred just before he joined the army, as more battalions became based at home, the drafting methods were improved and length of regular service for soldiers had been reduced from ten years to six years, followed by six years in the Army Reserve; this established a regular reserve for the first time. Thus, just under two years after his commissioning, his regiment’s two battalions became ‘county regiments’ alongside the rest of the infantry of the line. This involved a slight name change, so his unit became 1st Battalion, the Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment, establishing a special relationship with the county of Surrey.

Cardwell divided the country into sixty-six brigade sub-districts, each of which had a depot and two regular battalions, one of which would normally be abroad.41 Recruits were to be primarily taken from an allocated territorial region and the training depot was located within the same area. For Charles Monro’s regiment, this was to be the county of Surrey with the depot at Stoughton Barracks, Guildford. Each regiment was allocated a militia battalion and one or more volunteer battalions (the equivalent of today’s Territorial Army/Army Reserve). For the two Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment battalions, this meant joining with the 3rd Militia Battalion and four volunteer battalions – the 1st at Croydon, the 2nd based at Guildford, the 3rd in Bermondsey and the 4th in Southwark.42 Regulars and militia received their initial training at the Guildford depot. The regular soldiers then joined the home 1st Battalion which was responsible for providing drafts to the linked 2nd Battalion overseas in India.

The changes in the army were not perfect, as they rarely are; the home battalions were not necessarily happy with their role and sometimes shunned their new relationship with the militia and volunteers. The shorter lengths of service were not ideal for overseas, and home battalions that had to be deployed abroad in an emergency still had to take recruits from outside their areas.43 Lord Roberts was to blame the developing new recruiting system for the concentration of too many young and immature recruits sent to Zululand in 1879. However, territorial connections were established that still exist today and this helped generate cohesion within regiments.44 ‘The distinguishing points of the new army were short service and a Reserve, linked battalions, and localization of half the Army in Britain.’45

‘Professionalisation’ was one of the reasons for the various changes going on around Second Lieutenant Charles Monro. Whilst the purchase of officers’ commissions had ceased in 1871, in 1881 Childers was improving non-commissioned officers (NCOs) ‘pay, prospects and pensions’.46 Corporals were to be able to extend their service, in stages, to twenty-one years and gain a pension, whilst sergeants were able to serve the same length of time, were guaranteed a pension and were given separate accommodation. Junior NCOs became responsible for discipline in barrack blocks for the first time and the most senior NCOs, the regimental sergeant majors and regimental quartermaster sergeants gained a new status as intermediary ranks between NCOs and officers.

Simultaneously, compulsory retirement ages and set pensions at those ages were introduced for officers, and more field officers, specifically majors, were established in units to encourage junior officers’ aspirations for promotion. Childers also introduced an Army Act to improve and modernise disciplinary procedures. Charles Monro was learning his trade at a time of great modernisation in the army, though service based in the quiet garrison town of Colchester for nearly three years must have been a little frustrating compared with imperial soldiering elsewhere in the world.

Second Lieutenant Monro (standing, fourth from the right) with 1st Battalion Queen’s, Colchester, c. 1879/80. (Surrey History Centre. QRWS 2-13-2-5)

Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Kelly-Kenny took command of the 1st Battalion, the Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment in 1882 just as this major army reorganisation was still taking place.47 He had seen operational service in the China War of 1860 and in the Abyssinian Expedition of 1867–68 and had a successful career leading to the very senior appointment of adjutant general in 1901. Charles Monro seemed to flourish under his tutelage as, despite his poor Sandhurst results, after two years he was appointed adjutant, the key staff officer within his battalion. This post was, and still is, the right-hand man to the commanding officer. Thomas Kelly-Kenny must have liked what he saw, as Charles Monro was to serve again as one of his key staff officers in the Boer War, when Kelly-Kenny was a divisional commander.

The battalion was sent to Ireland in 1883, where it remained at various locations for the next seven years. This period of its history is not marked by any significant events, though some aspects of the British Army’s role in the country do not appear to have changed much from modern times. According to this quotation from the battalion’s deployment to Belfast in 1886, ‘Here they were employed for several months in the difficult and unpleasant duty of piqueting the streets to prevent disturbances between the Orangemen and the Nationalists.’48 One soldier was murdered by a revolver bullet ‘by mistake’.

Meanwhile, Charles Monro relinquished his adjutancy in July 1886 and was selected for the Staff College entry in February 1889 after ten years of relatively quiet soldiering in England and Ireland.

The Staff College

To be selected for the Staff College, Camberley, which was in the same grounds as the Royal Military College of Sandhurst, was a major step forward for Charles Monro. Attendance on the two-year course was increasingly being seen as important for higher command, though not essential. A student could have had a steady and perhaps nondescript military career up to that point, but with a good performance at the Staff College behind them the opportunities were opened up for a more rewarding future.

Not everyone in the army thought that this elitist and professional approach was necessarily the right way to develop a career. Some regiments were not keen on sending their officers on the course, so Lord Allenby, for example, ‘was the first officer of the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons to go there – in 1896’, just seven years after Charles Monro.49 Charles Monro’s biographer, Barrow, who also attended the 1896 course along with the future Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, commented about the attitude of his own commanding officer, who was:

… one of the many senior officers of those days who, having an unreasonable antipathy to the Staff College, regarded the staff with hostility, labelled all who were entitled to the letters Passed Staff College (PSC) after their names as Staff College pundits, and considered polo, hunting, shooting and a knowledge of drill all the education necessary to produce a thoroughly efficient officer.50

Attendance was not essential for future high command, but it helped. Robbins points out that in the First World War General Sir Henry Horne ‘would be the only gunner to command an army in France but also the only one of the ten Army Commanders not to have passed Staff College’.51

There were normally thirty-two spaces on the course each year, so sixty-four students were in the college at any one time. For the February 1889 intake, twenty-eight were awarded by competition, including four for the Royal Artillery, two for officers of the Royal Engineers, three for the Indian Army and one Royal Marine.52 Charles Monro gained one of the eighteen competition vacancies designated to the cavalry and infantry combined. The remaining four places were nominations.

For most candidates, commanding officer’s reports were critical, alongside successful examination results. Charles Monro passed his exam in June 1888, though sixteen of the sixty-eight applicants failed. He scored 2,655 points, earning the creditable sixteenth highest mark out of the fifty-two who did pass and proving his intelligence.53 The subjects tested were mathematics, fortification, military topography, tactics, a language (French, German or Hindustani), military history, geography and military law.

The average age of students at the Staff College was 30 years old and most were captains or promoted captain whilst on the course. On entry, Charles Monro was a 28-year-old lieutenant who received his promotion to captain on 24 July 1889.

There were two terms in each year and during the Easter and summer leaves battlefield study tours on the Continent took place. The curriculum consisted of military art and history, fortification and artillery, field fortification and minor tactics, military administration and staff duties, military topography, reconnaissance and practical field work, military law, a modern language (French or German were compulsory for the British Army students, Hindustani for the Indian Staff Corps; Russian was also an option), natural sciences and, of course, riding. Sport was encouraged, particularly the college drag hounds, coach driving, squash, golf, boating, polo and cricket. Charles Monro certainly played for the cricket XI, as proven by an existing picture in the Staff College archives, and Barrow and Godwin-Austen state that he was their captain.54

Younghusband had clear views about the importance of balancing academic studies and sport:

Every manly sport, and pastime, is thoroughly encouraged, and supported; on the admirable principle that no man can have clear head, and steadfast nerves, unless he is in sound health, and excellent bodily training, a consideration which is often overlooked in the modern craze for competitive examinations.55

Monro was an active proponent of this philosophy, both in riding and cricket.

Staff College cricket, 1889. Monro is seated, second from the left. (Defence Academy Archives)

Once graduated, officers were then attached to unfamiliar branches of the army for four months. Quite a lot of the study was practical, though perhaps at too low a level, and there were two main sets of exams – one at the end of the first year and one at the end of the course. For example, the military topography exam in the second year included:

Rapid Sketch on horseback – 100 marks available.

Field Sketch, and making use of maps on the ground – 100 marks.

Theoretical Paper, embracing the whole subject – 100 marks.56

Reconnaissance abilities were important in those days, as now, but technology was limited. Without high-quality cameras or electronic gadgetry, intelligence in the field usually relied on verbal line-of-sight reporting supported by hand-drawn sketches.

The commandant of the Staff College during Charles Monro’s time was Brigadier General Cornelius Francis Clery, who held the post from 1888–93. He was also an infantryman, who had seen active service in the Zulu War of 1879, Egypt in 1884 and the Sudan in 1884–85.57 Although he had written a book on minor tactics, he has been described as ‘a distant character who was only rarely seen by the students’.58

The main professor in military art, history and geography was Colonel John Frederick Maurice, who had assumed the appointment in 1885. He had been commissioned into the Royal Artillery and served as personal secretary to Sir Garnet Wolseley in the Ashanti Campaign of 1873–74. He had also taken part in the Zulu War in 1880 and the Egyptian expedition of 1882. He was chosen as part of the ‘Wolseley Ring’ for his clear brain, experience and hard work, yet was also known for being absent-minded, impractical and of ‘a violently argumentative nature’.59 However, ‘he had a gift for making the subject of military history absorbingly interesting’ and encouraged officers to think for themselves and to study military campaigns in depth.60 Laudably, he wanted his students to establish the facts of a military event and the causes behind those facts and then identify conclusions useful for the future. This analytical approach would put Monro in good stead in later years.

The ‘Report on the Final Examinations’ at the Staff College, held in December 1891, provides the evidence that Charles Monro passed the final tests.61 Lieutenant General Biddulph’s comments include the list of officers who passed, though Captain Charles Monro is not given any special mention for his performance in any subject, unlike some of the others. An example of a typical comment concerns military topography results:

The horseback sketches were decidedly the more accurate and reliable, although the attempt to combine rapidity of execution with accuracy and completeness of detail, generally resulted in some sacrifice of the two latter essentials. Captain F. N. Maude, Royal Engineers, executed his sketch in remarkably quick time (four hours and fifteen minutes),62 but at the expense of both neatness and accuracy; while Captain N. B. Inglefield, Royal Artillery,63 took twenty-five minutes longer, but at a sacrifice of completeness of detail.64

Interestingly, F. N. Maude, who was an outspoken character, later commented adversely on the style of teaching. Despite Colonel Maurice’s efforts, Maude believed that ‘instead of making the Staff College into a true University, for experimental and original research, we made it a kind of repetition school for the backward’.65

The military art and history paper concentrated on questions related to the Franco-German War of 1870, the benefits for and against the use of the rifle or lance by cavalry, the increase of artillery in the German Army and principles of infantry in the attack from 1866 to 1891.

The 1891 graduates were to include one general of the future (Charles Monro), two lieutenant generals (Robert Broadwood and Ernest De Brath) and two major generals (J. H. Poett and Montagu Stuart-Wortley), but they were also mixing with a batch of other future senior officers from the year before and the following course.66 Charles Monro was, therefore, part of a relatively well-educated elite when he graduated from the Staff College, despite some of the criticisms of its methods. Two years’ professional study must have added value to his capability, compared with others who did not receive the opportunity. Brian Bond summed up his findings from comments made by students in the 1880s: ‘The general impression of those who were students in the 1880s is that these were two very happy years, that they were of some professional value, but that the work did not make very rigorous demands.’67

Colonel John Maurice had worked hard to improve the course and it was to become more practical after Charles Monro’s time at the college. More reforms were to take place under the stewardship of the new ‘professor’, Colonel George Henderson, from 1892, and the new commandant, Colonel Henry Hildyard, from 1893. On handover to Henderson, Maurice stated, ‘I am deeply conscious that at present the Staff College produces a monstrous deal of bread for very little sack. The able men benefit greatly but from the ruck we have turned out I fear me some cranks and not a few pedants.’68

Field Marshal Sir William Robertson, who had joined the army as a private soldier in 1877 and was appointed the commandant of the Staff College in 1910, had a more positive view of the college’s value as an institution:

Another advantage of the course is that the students are taught the same basic principles of strategy and tactics, and are accustomed to employ the same methods of administration. It is necessary in any business that the men responsible for its administration should abide by the same rules, follow the same procedure, and be fully acquainted with the best means for ensuring smoothness and despatch; and nowhere is the necessity greater than in the business of war, where friction, delay and misapprehension are fraught with so many possibilities of mischief. It is only by the establishment of a sound system with which all officers are thoroughly familiar that these rocks can be avoided.69

He goes on to state the importance of a ‘common school of training’ and the fact that when he became Chief of the Imperial General Staff there was a common understanding between him and different commanders around the world, including Charles Monro in India. He wrote, ‘That the mutual agreement and excellent comradeship established between Staff College graduates during the twenty years previous to 1914 were of inestimable value to the Empire throughout the Great War is, in my humble belief, beyond contradiction.’70

In a similar vein, Barrow, of the class of 1896 which included a number of future famous commanders, emphasised in his autobiography the importance of the Staff College in creating bonds of understanding and friendship:

In one other way, combining pleasure and education, the Staff College course has a value not to be found in educational establishments outside the services. It consists in the comradeship of men and diverse characters and opinions but speaking the same professional language, holding the same views on all matters of conduct, and trained in the same school of military honour. Lastly, it is at the Staff College that many a permanent friendship is formed.71

Professor Brian Holden Reid’s War Studies Paper of 1992 is an excellent assessment of the Staff College from 1890–1930, catching the end of Charles Monro’s attendance there. Whilst acknowledging that reconstructing what was taught there at a given date is not easy and that there was a lot of criticism in the 1920s about the pre-First World War syllabus, he notes, ‘in many ways the heyday of military history at the Staff College’ was in the period 1880–1914.72

Staff College, 1889–90. Monro is standing, third row up, fifth from the left. (Defence Academy Archives)

British staff officers were not generally criticised for their administrative failures in the First World War, but lack of leadership and an obsession with parochial detail rather than universal strategic analysis. The great military forward thinkers of the 1920s, Captain Basil Liddell Hart and Major General J. F. C. Fuller, criticised the detail. Liddell Hart wrote, ‘And the method of study was one of excessive concentration on detail rather than an inquiry into the broad principles of the leader’s art and comparison of the great captains of all ages.’73 And J. F. C. Fuller:

At present we are controlled, through no fault of its individual members, by a hierarchy which, though autocratic, is sterile. It fears initiative, it is terrified at originality and it suppresses criticism. Thus ‘a new spirit’ was required at the Staff College, ‘the spirit of loyalty to truth’.74

Holden Reid deduces that ‘these failings clearly reflected the mode of instruction which produced mentally unadventurous graduates’ and ‘the Staff College produced sound technical staff officers rather than imaginative, reflective commanders’.75 However, this was not Field Marshal Robertson’s view; he was a believer in the need for detail.

It has been necessary to dwell on the Staff College experience, as two years of study for Charles Monro was to critically influence the rest of his career, both for professional reasons and for the personal contacts that he made. The evidence shows that some effort was made to shape intellectually the future high-level commanders of the First World War, which did involve intelligence, initiative and application. Instruction was gradually improving as the years progressed, through the efforts of some key ‘professors’. However, there may have been too much of a concentration of low-level tactics and detailed procedures, rather than the practical writing of orders and the wider study at the operational and strategic levels of war. With hindsight it is easy to be critical, and the author, who has been both a student and a teacher at the Staff College, is well aware of how critical bright students can be of any syllabus, no matter how well considered it may be. At this time, the army was generally engaged in small wars where knowing the details of reconnaissance, movement, logistics etc. were seen to be more important than the strategic forward thinking needed for a major European war.

Notes

1 Lubbock (1955), p.181.

2Argus newspaper, Melbourne, Monday, 19 March 1860.

3 Barrow (1931), p.268.

4 Information from current family members: Alastair Monro Gaisford and Dr Christina Goulter.

5 A tenth child, James, was born in 1854 but died as a baby.

6 School archivist information from The Sherborne Register and Shirburnian magazine.

7 Gourlay (1971), p.122.

8 Barrow (1931), pp.16 and 265.

9 Ibid. p.19.

10 Gourlay (1971), p.139.

11 School archivist information from The Sherborne Register and Shirburnian magazine.

12www.sherborne.org/about us/a-brief-history.

13 Gourlay (1971), p.139.

14 Moore-Bick (2011), pp.19–20.

15The Western Gazette, Friday, 1 July 1921.

16 Thomas (1961), p.151.

17 Barnett (1974), p.314.

18 Robbins (2005), p.3.

19 Turner (1956), p.243.

20 Yardley (1987), p.40.

21 Younghusband (1891), p.iv.

22 Ibid. p.6.

23 Hamilton, Ian B. M. (1966), p.12.

24 Younghusband (1891), p.13.

25 Heathcote (1978), p.17.

26Hart’s Annual Army List (1881), p.347. George was commissioned into the 101st (Royal Bengal Fusiliers) on 16 February 1878. He later served in the Worcestershire Regiment and was retired as a major in 1904.

27 Mockler-Ferryman (1900), p.40.

28 Shepperd (1980), p.79.

29 Heathcote (1978), p.18.

30 Thomas (1961), p.140.

31 Barrow (1931), p.20.

32 Mockler-Ferryman (1900), p.112.

33 Marshal-Cornwall (1973), p.2.

34 Thomas (1961) pp.143–44.

35 Ibid. p.132.

36 Barrow (1931), p.20.

37 The regiment has been amalgamated over the years and is now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment (PWRR). The author is a deputy colonel of the PWRR.

38 Foster (1961), p.59.

39 Irwin (2004), pp.32–35; Yardley and Sewell (1989), p.46.

40 Bond (1961), p.236.

41 Crowley, Wilson and Fosten (2002), p.42; Musketeer (1951), p.600.

42 Anonymous (1953), p.37.

43 Strachan (1997), Chapter 9.

44 Myatt (1981), p.56.

45 Bond (1962), p.115.

46 French (2005), p.21.

47 Davis (1906), Vol. VI, p.161.

48 Davis (1906), Vol. V, p.177.

49 Turner (1956), p.266.

50 Barrow (1942), p.41.

51 Robbins (2010), p.28.

52 Younghusband (1891), Chapter IV; War Office Report (1888), p.2.

53 Ibid. p.6.

54 Barrow (1931), p.20; Godwin-Austen (1927), p.227.

55 Younghusband (1891), p.154.

56 Ibid. p.240.

57 Young (1958), p.55.

58 Jeffery (2006), p.17.

59 Bond (1972), p.137.

60 Barclay (1958), p.176.

61 Report (1892).

62 F. N. Maude retired as a colonel, was a military author and ran the book reviews for the Journal of the Royal United Service Institution.

63 N. B. Inglefield was a key cricket player for the Royal Artillery.

64 Ibid. pp.6–7.

65 Bond (1972), p.126.

66 Godwin-Austen (1927), p.227.

67 Bond (1972), p.141.

68 Barclay (1958), p.176.

69 Robertson (1921), p.89.

70 Ibid. p.90.

71 Barrow (1942), p.46.

72 Holden Reid (1992), p.3.

73 Liddell Hart (1927), p.174.

74 Fuller (1935), pp.122–23.

75 Holden Reid (1992), pp.5 and 11.

2

SERVICE OVERSEAS ANDOPERATIONAL EXPERIENCE

The time had come for overseas service and operational experience for the 31-year-old Captain Charles Monro. This was, and still is, an essential prerequisite for any future senior commander. Most of his next nine years were overseas, starting with garrison duties in Malta and India, but more excitingly with company command on the Mohmand and Tirah expeditions in the North-West Frontier region of the Indian Empire and then as a key staff officer in the South African Boer War.

He had re-joined his original infantry unit, 1st Battalion, the Queen’s (Royal West Surrey) Regiment, and was posted with the other 800 officers and men to Malta at the end of 1892. According to the Regimental History, this was a pretty uneventful three-year garrison posting.1 He was one of the five battalion captains with limited duties in that environment. However, he was obviously seen as an officer who needed opportunities as he temporarily filled two important roles there, away from the battalion – as a temporary aide-de-camp (ADC) to the governor, and as the acting brigade major to the local infantry brigade commander.2 Both of these posts were ‘right-hand man’ appointments, particularly the latter, so he was starting to be given trusted key authority. ADCs do pick up some basic tasks, though, and his initial reaction to that attachment was that he was ‘no good at carrying ladies’ cloaks’.3

Caricature of Captain Monro, company commander, F Company. (Surrey History Centre. QRWS 1-16-9-4)

India

In February 1895, his battalion arrived at its garrison location in India: Amballa (now Ambala). There were fifty-two British infantry battalions in India at the time, out of a total of 141, and thirteen were in the Punjab command. Ambala is a long way from Surrey. Situated in the far north of India, now in the state of Haryana, bordering with the Punjab, it is still an important Indian Army and Air Force base.

The battalion’s eight companies were quickly despatched across the region in order to show presence and keep law and order where necessary. Apart from a short time as brigade major to Brigadier General William Penn Symons, Charles Monro, as one of the company commanders, had a great deal of local authority and independence away from battalion headquarters – the company level of operations was critical.

The Indian Army, which worked side by side with the British Army, was going through a significant reorganisation in the same year his battalion arrived. In October 1895, the new Indian Army was formed, the three old Presidency armies being absorbed later in 1903. It was organised into four new commands: the Punjab, Bengal, Madras and Bombay.

The period 1894–99 in India has been described as ‘five years of natural calamities, troubles on the Frontier, and symptoms of political unrest under a weak, colourless Viceroy, Lord Elgin’.4 An import duty had been imposed back home on Indian cotton in 1894 and there was widespread drought in 1896–97, which mainly affected central provinces but also parts of the Punjab. This famine was later followed by an even worse one in 1899–1900, which affected one-third of the country and resulted in many human lives and cattle lost. In addition, bubonic plague broke out in Bombay in 1896 and spread to parts of the country, including the Punjab – 193,000 people died in India and there was little medical knowledge about its cause or treatment, though it was known that isolation helped stem its advance.5

A key political decision was made during this period that still affects politics in the region today; the establishment of the Durand Line, a demarcated boundary between India and Afghanistan. This came about from two joint Afghan and Indian commissions of 1894–96, the Indian Mission being led by Sir Mortimer Durand. For the first time, the no-man’s-land between the two countries was formally split. This resulted in different tribes falling into each of the two countries’ spheres of influence, though due to the nomadic nature of many of the tribes, the line ended up splitting some of them. At the time, it was thought that this would stabilise the region – it had the opposite effect.

The regiment, like much of the British Army, had experienced service in India before. The 1st Battalion had been there for twenty years from 1825–45, including deployment during the First Afghan War, whilst the 2nd Battalion was in India, including two years in Burma, from 1878–94. This latest tour would last thirteen years, from 1895–1908, though Charles Monro would only be with the 1st Battalion for the first four.

Captain Monro was remembered as a professional, selfless company commander who looked after his men in F Company. He generally had a good boyish humour, but occasionally displayed a fiery temper. He was always sympathetic to subordinates and was not afraid of responsibility.

The British military presence had been adjusted since the Indian Mutiny of 1857. The ratio of British soldiers to Indian was significantly increased, following a recommendation of an 1859 royal commission, which led to ‘the maximum reached being 62,000 (British) to 135,000 (Indians)’, though 30,000 more troops were available in the 1880s, due to North-West Frontier threats.6 Also, brigades were deliberately mixed British and Indian units to ensure a ‘backbone’ of reliability.

Any new weaponry went to the British first and artillery was carefully controlled. For example, the new bolt-action, magazine-fed Lee–Metford rifle, sighted to 2,800 yards and quick firing, was issued to British battalions, whilst the older slower firing single-loading Martini-Henry was the standard Indian infantryman’s personal weapon. One relatively new weapon was the Maxim gun, an early machine gun fed by ammunition belts of 250 rounds and sighted to 2,500 yards. One was issued to each British infantry battalion and some cavalry regiments. Eight soldiers looked after each gun, including the immediate three-man crew. Their fire could be very effective, particularly in defensive positions, though they were not very reliable. Even so, they could cause havoc amongst concentrated groups of enemy, leading to the historian Hilaire Beloc writing, ‘whatever happens, we have got the Maxim gun, and they have not’.7 The British did not want a repeat of the Indian Mutiny, so the best weaponry was placed in the most trusted hands.