15,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

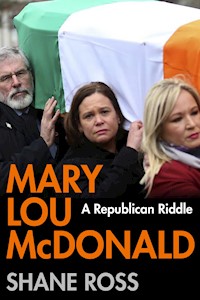

Mary Lou McDonald is the bookies' favourite to be Ireland's next Taoiseach. She would be the first woman to reach the office, and the first Sinn Féin leader ever to enter government in the Republic of Ireland. But how did a quintessentially bourgeois woman become the leader of a political party with such recent links to terrorism? This exhaustively researched biography unearths new details of her family background and her privileged education, as well as her initial foray into politics through the more traditional Fianna Fáil party. It explores her unusually late commitment to political life and traces her mysterious but meteoric rise through the ranks of Sinn Féin and her relentless drive to reach the top of the party. Scrupulously fair and balanced, Mary Lou McDonald illuminates its subject's political awakening and her interactions with the hard men of the IRA, while posing important questions about the evolution and future of Sinn Féin.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2022 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Shane Ross, 2022

The moral right of Shane Ross to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 589 2E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 590 8

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Contents

INTRODUCTION:

The Riddle of Mary Lou

CHAPTER 1:

The Skeleton in the Cupboard

CHAPTER 2:

From the Cradle to the Altar: A Politics-Free Zone

CHAPTER 3:

Into the Arms of Gerry Adams

CHAPTER 4:

The Anointing of Mary Lou: The Fast Track to Europe

CHAPTER 5:

Desperately Seeking a Dáil Seat

CHAPTER 6:

The Mansion in Cabra

CHAPTER 7:

A Star Takes the Dáil by Storm

CHAPTER 8:

Adams Calls the Shots

CHAPTER 9:

Playing the Cemetery Game

CHAPTER 10:

To Hell and Back

CHAPTER 11:

A United Ireland or Bust

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

THE RIDDLE OF MARY LOU

Mary Lou McDonald never wore a balaclava. She never pulled a trigger. She never planted a bomb. She has never even been in prison. Indeed, it is unlikely that she has ever incurred as much as a speeding fine.

Today she leads a party full of hardened IRA veterans. Some are still puzzled by her selection as leader of Sinn Féin. Others are pleased that she is in control. She will never qualify for membership of the Felons Club, the exclusive hostelry in the heart of west Belfast frequented by IRA ex-prisoners. No doubt she would be warmly greeted as a guest, but she sports none of the wounds of war required for automatic admission.

The Felons Club is a semi-private hostelry at 537 Falls Road. According to its bye-laws, it was established ‘to foster and maintain among Irish Republicans friendships formed during imprisonment or internment as a result of their service to the Irish Republican cause’. It is a meeting place for many Irish Republicans, particularly IRA members who served time in prison. Full membership is restricted ‘to those who have been imprisoned or interned for their Irish Republican beliefs’.

Outsiders are allowed in, but ‘shall not be supplied with intoxicating liquor in the club premises unless upon the invitation and in the company of a member’. The rule would seem to more comfortably belong in posh, gentlemen-only, exclusive London clubs than in a bolthole for former IRA paramilitaries.

Mary Lou McDonald’s failure to have been part of the IRA campaign is her greatest liability, and her greatest asset. She will never be the full ‘Shinner’. She will never command the same awe or respect as Gerry Adams or Martin McGuinness with republicans north of the border. Former occupants of the Maze prison are acutely aware that she never had blood on her blouse, not having suffered the indignities, physical brutality and pain of the long campaign. Adams and McGuinness were both war heroes who would qualify for the Felons Club. Yet these two former IRA leaders, from Belfast and Derry respectively, are the men who thrust greatness upon the well-spoken young woman from Rathgar in middle-class Dublin, handing her a mandate to lead both the IRA veterans and Sinn Féin newbies to the next stage in the party’s pursuit of power, north and south.

In the Republic, Mary Lou’s detachment from the grisly IRA war of terror is an imperative if she is to win the Taoiseach’s office. In the refined, hedge-clipped avenues of suburban Dublin there is little tolerance for the physical violence championed by her mentors, Adams and McGuinness, in the North over three decades. The gross injustices of Bloody Sunday and other British Army atrocities are deplored, but there is still no appetite for ambiguity or double-think on a policy that risks returning Ireland to former days. Mary Lou’s task is to convince Ireland’s citizens that she is a peacemaker, while reassuring militant Northern nationalists that their fight was not in vain; that the promised land of a united Ireland is coming and that it could not have been done without their sacrifices. Today she stands on the verge of being the first ever female Taoiseach, the first Sinn Féin cabinet minister in the Republic, but, more importantly, the president of a party that is in power simultaneously both north and south of the Irish border. History beckons.

Yet precious little is known about Mary Lou the person. The contradictions in her life – so far – prompt countless challenging questions. She is dogged by unsolved riddles.

As the author of this book, I must make a confession – not of a vested interest, but of a prejudice, a weakness, perhaps. I have known and liked Mary Lou McDonald for many years. I worked with her while we were both in opposition on the Dáil’s Public Accounts Committee (PAC) from 2011 to 2016. She was excellent company, lively and amusing. As a performer in the sittings of the committee, she was second to none. She would go straight for the jugular. Witnesses feared her sharp tongue and her speedy ripostes. She was well briefed by the highly competent Sinn Féin back office, which was grooming her for greatness. I confess to a similar love of the limelight, but she was a media darling with a talent for the sound bite that left me and others in the halfpenny place. We competed for the cameras, but it was a pointless contest. Mary Lou McDonald was a combatant without parallel for media coverage. Along with the PAC chair, John McGuinness, and others, we were given a dressing-down by the chief justice, Frank Clarke, for our aggressive questioning of Rehab boss Angela Kerins. The judicial rebuke didn’t take a feather out of Mary Lou. She was refreshing, irreverent and fearless.

When I became a minister in 2016, my relations with Mary Lou and Sinn Féin remained good. Despite sitting on the opposition benches, the party supported my push for reform of the blatant political patronage in judicial appointments and of drink-driving laws. In turn, I willingly received Sinn Féin delegations, much to the horror of some of my Fine Gael cabinet colleagues. When Mary Lou asked me if, as minister for sport, I would visit a boxing club in her Dublin Central constituency, I willingly did so.

Consequently, in 2021, when I decided to write this biography, I had anticipated her co-operation, albeit limited. I understood that Sinn Féin is an ultra-secretive organisation that likes to control its own message. In June 2020, I rang Mary Lou, asking her to meet me for half an hour without divulging why. I wanted to tell her what I was about face to face. She graciously agreed, although at the time she was particularly busy in crisis talks in Northern Ireland, negotiating the proposed Irish Language Act.

The Dublin Bay South by-election was in full swing at the time. Mary Lou was campaigning intensely on the ground, so wanted to meet somewhere close by in the embattled constituency. She opted for a private house meeting, rather than a public café, providing her with a short break from pounding the pavements. We met, alone, in a ‘safe’ house belonging to my son, Hugh, in Ranelagh, Dublin 6.

When she arrived, I told her of my intention and the reasons for writing this book, primarily because she was likely to be Ireland’s next Taoiseach. She looked doubtful. She was bemused but noncommittal about her attitude to the project. She was modest, suggesting that she might even be too boring for a biography. I said that I would appreciate it if she would open a few doors, in particular to her family, because stories of her upbringing, her publicly unknown siblings, her mother, her father and her husband would be compelling. I had met her charming and highly intelligent younger sister, Joanne, a couple of times, her mother, Joan, and younger brother, Patrick, briefly, but knew nothing about the rest of her immediate family, let alone her reclusive, heretofore almost invisible, husband, Martin Lanigan. All six people merited a little exposure if we were to paint a fuller picture of the people who helped to shape the mysterious Mary Lou.

They have turned out to be a fascinating family, with talents and shortcomings that make her formative years assume a new importance.

Mary Lou asked me not to go into the details of her parents’ separation. I assured her that, though details about her background were essential to the narrative, I had no curiosity about any animosity between her mother and father; the book was intended to be neither a polemic nor a hagiography. And it was not designed to advance or to torpedo her ambitions to be Taoiseach. If there were important stories, good or bad, they would be published. I would speak to her critics, as well as her family and supporters. I specifically mentioned the case of Máiría Cahill, the woman raped by an IRA man when she was only sixteen years of age. Otherwise, if Mary Lou was discovered to have ‘guns in the cupboard’, of course, that would have to emerge, but I was not looking for them. She responded that there were none.

Overall, Mary Lou seemed a bit taken aback. She would need to ‘consult’ with a few (unnamed) people and would get back to me within a few days with a response about whether she could open any doors. She glanced at my son’s garden and mentioned that her husband, Martin, was a good gardener. It was the first time I had ever heard her mention him. We parted as friends. Following the publication of this book, I hope we can remain so.

The omens are not good.

Mary Lou phoned me a week later with the result of her consultations. She did not identify the people to whom she had spoken. She was not willing to assist me with the book. She felt it was ‘premature’. She would not be asking anyone to speak to me, nor would she be telling anyone to refuse. I told her that I would almost certainly have questions to put to her when I had finished my research. She said there was no guarantee that she would agree to answer them.

I interpreted Mary Lou’s response as an attempt to dissuade me from putting pen to paper. I knew there would be a negative reaction from Sinn Féin, a party that likes to hold a rigid control over its members, regardless of rank. It would be a harder task if she were to put a muzzle on anyone, but she had now ‘consulted’ with certain people and had reached a conclusion. I could guess the names of some of those to whom she had spoken about the proposed biography. I expressed disappointment and we wished each other well.

Mary Lou’s career so far poses many puzzles. The most frequently asked question is how a middle-class, privately schooled woman has emerged as the leader of a united Ireland movement that has traditionally been driven by Northern working-class males, many of them unapologetic advocates of IRA violence?

Another question has attracted even more immediate attention. Do the IRA veterans, the volunteers, the backbone of Sinn Féin in Northern Ireland, approve of her? Is their acceptance of her leadership conditional? Or, worse still, do the Northern hard men control her? What is the new leader of Sinn Féin’s true relationship with them? Is she mistress or servant?

We seldom catch a clear glimpse of the powerful Sinn Féin old guard, former members of the supposedly disbanded IRA Army Council. One such rare occasion occurred, ominously, as recently as 30 June 2020, at the funeral of former IRA intelligence chief Bobby Storey.

Storey was an icon of republican folklore, even in his lifetime. He was indisputably in the IRA ‘army’. He was a legend because he had masterminded some spectacular dramas, including the mass escape of thirty-eight IRA prisoners from Long Kesh prison in September 1983. He had continued to plan meticulous illegal operations, such as the £26 million Northern Bank robbery, carried out in 2004, long after the 1998 ceasefire, which Storey supported. The IRA tried to spin him as some sort of Robin Hood character because of his ‘success’ in the bank heist, but opponents insist that he was a thoroughly nasty piece of work, known darkly as an IRA ‘enforcer’ for good reason.

Mary Lou showed up at Storey’s funeral in Belfast. As leader of Sinn Féin, it would have been hard for her to plead a prior engagement, yet it was a paramilitary parade with trappings to match. No volley of shots was fired over the coffin, but the identical black trousers, white shirts, black ties and Easter lilies worn by the citizens of west Belfast lining the streets bore the hallmarks of an army of disciplined followers, rather than of an angry rabble or a gathering of family friends in mourning.

An almighty row broke out about the lack of social distancing at Storey’s funeral at a time when Covid restrictions were in force. Many expected that prosecutions would follow, with the names of Mary Lou and Northern Ireland’s deputy first minister, Michelle O’Neill, in the frame. The prosecutions never happened. Yet Mary Lou looked distinctly uncomfortable in the photographs taken of herself closely bunched with former IRA chiefs outside the Storey family home, marching behind the funeral cortège.

Her discomfort was understandable. It was probably caused by the company she was keeping rather than by any fear of catching Covid for a second time.

The coffin carriers at the funeral were the key. Their identity was a message from the hard men. The people carrying Storey to his last resting place were not his family and not Mary Lou or Michelle O’Neill, the democratically elected leaders of Sinn Féin north and south. They were republican veterans. No non-combatants needed to apply as the final coffin carriers. Their exclusively military status was a gesture of defiance, evidence that the IRA Army Council perhaps still existed. The coffin carriers were the elite of the decommissioned army. Gerry Adams was joined by Storey’s fellow Maze escaper, Gerry Kelly, to carry Storey on his final journey. Seán ‘Spike’ Murray, who was convicted of explosives offences, Martin Ferris, who served ten years for smuggling arms in 1984, Seán ‘The Surgeon’ Hughes, the unelected republican leader from south Armagh, and Martin ‘Duckster’ Lynch, who served ten years for possession of a rocket launcher, also shouldered the burden.

Mary Lou looked on. So did ‘non-army’ Sinn Féin TDs from the Republic, Pearse Doherty, Rose Conway-Walsh and Matt Carthy.

Was this a signal to Mary Lou that, while she was welcome at their solemn gig, the ‘army’ still ran its own show? The funeral was on its terms. When in Belfast, do what the Belfast boys do. It provoked the question: had they fully accepted the leadership of the middle-class woman from south Dublin? Or were they still operating in a parallel paramilitary universe?

Mary Lou parried later hostile media questions about her attendance at the funeral of an IRA leader with the reply that Bobby Storey was ‘a champion of the peace process’. Which was rather stretching it. He was a lot more than that.

A few days after Mary Lou had told me that she would not stand in my way of talking to anyone, I decided to hit the phones in pursuit of the coffin carriers from the North. I rang MLA (Member of the Legislative Assembly) Gerry Kelly’s constituency office in north Belfast. He was not there, but I left a message with a request for him to ring me.

Gerry Kelly is a man with a serious IRA record. He was sixty-nine in April 2022, part of an ageing group of former IRA activists whose influence is a topic of hot debate. He was convicted of the 1973 Old Bailey bombings along with the even-better-known Price sisters, Marian and Dolours. Kelly was sentenced to two life sentences plus twenty years. According to the Sinn Féin account, he went on hunger strike for 206 days in Britain and was force-fed 167 times. He was transferred to the Maze prison outside Belfast. While escaping with thirty-seven others in 1983, armed with a smuggled handgun, he shot a prison officer, who survived despite serious head wounds. Kelly went on the run for three years, but was re-arrested in the Netherlands in 1986. After his release in 1989, he joined the Sinn Féin negotiating team and has been a key republican figure ever since. I hardly expected an early response from a busy MLA, but within half an hour my mobile rang. It was Gerry Kelly.

I explained to him that I was writing a book about Mary Lou McDonald. I would be in Belfast in the coming days and would appreciate a meeting with him and his Sinn Féin colleague, Seán ‘Spike’ Murray. I was chancing my arm.

Kelly was charming: ‘there should be no problem’. He even promised that he’d talk to Seán Murray about meeting me.

I had hit the jackpot on day one. The Army Council was coming out to play.

A few days later, when I rang back to fix the time and place of the appointment, Gerry had vanished. In response to a second call, he was in Kerry on holiday. I was asked to ring him on his return. Several more calls encountered the same brick wall. There was little point in me, a journalist, setting out in hot pursuit of a man who had given the European forces of law and order the slip for years when he was on the run.

In the following days and weeks, a pattern emerged. The replies to my calls to IRA diehards from Belfast and Derry were unambiguous and unanimously negative. Even Gerry Adams showed hints of humour. Since we follow each other on Twitter, I sent Adams a direct mail:

Hi Gerry

I do hope that your wife Colette is better now [she had contracted Covid] and all well with you. I know that you were reluctant to speak with me about my book on Mary Lou. I can assure you that it is neither polemic nor eulogy. In any case is there any chance we could meet for a cup of coffee in Belfast? I shall be up the week after next and the week after that. If necessary, the words ‘Mary Lou’ need not be uttered. Best wishes, Shane

By chance, I knew from that day’s Sunday Independent that it was Adams’s seventy-third birthday the following Wednesday. So I added: ‘How about Wednesday? I could bring you a birthday present?!! Congrats, Shane.’

Gerry Adams is known for many things. Humour is not one of them.

I received the following reply: ‘Nope Shane. Grma xo ga.’ I was puzzled. What in the name of God was ‘Grma xo ga’? Was it a coded message or had the great man’s finger slipped on his mobile phone’s digits?

When I received the message, I was lunching with my family. I put the question to them collectively.

My daughter, Rebecca, interpreted the puzzle: ‘“Grma” is go raibh maith agat – thank you. “xo” is a kiss and a hug and “ga” is Gerry Adams,’ she said.

‘Brilliant. Give me a response in Irish?’ I asked her.

My wife, Ruth, whose Irish is good, provided it. ‘You should reply “Tfr xoxo sr”, meaning “Tá failte romhat xoxo sr”. Translated into English, it’s “You are welcome, hugs and kisses, Shane Ross”.’

I sent the message. ‘Hugs and kisses’ was probably a bit over the top.

Other early responses from Northern Ireland replicated the Gerry Adams/Gerry Kelly line. Conor Murphy, minister for finance in the Northern Ireland Executive, convicted of being in possession of explosives and sentenced to five years’ jail in 1982, said no. Former Sinn Féin policy officer Danny Morrison, whose sentence in 1990 for kidnapping an IRA informer was later quashed, also said no. Martina Anderson, the Derry MLA convicted of conspiring to cause explosions, said no. Arthur Morgan, a former IRA prisoner who served seven and a half years in Long Kesh, replied after four calls. Arthur, a former TD with whom I had enjoyed many cups of coffee in the Leinster House members’ bar, said that ‘Mary Lou was in Brussels when I was in the Dáil. I was working flat out at the time to hold the seat.’ Arthur said no; he couldn’t help me.

Those who qualified for the Felons Club had got the message. They were all singing from the same hymn sheet. Those who were once ‘army’ were behaving like, well, an army.

I contacted others, this time in the Republic, all non-combatants, people who, like Mary Lou, had never worn a balaclava. Initially, no one said no. It was looking good.

Sinn Féin TDs David Cullinane and Aengus Ó Snodaigh initially said yes. In both cases we arranged to meet, but both men pulled out. Cullinane soon left a message saying he had ‘mentioned it to the Press Office. She [Mary Lou] had no problem with Shane but . . . I might give it a miss. Best of luck with the book, regardless.’

Aengus Ó Snodaigh TD was due to meet me in the TriBeCa restaurant in Ranelagh. He sent a text that morning: ‘Have to cancel today. Will ring later to apologise in person.’ He never did.

I spoke to other Dáil deputies, including Rose Conway-Walsh, Donnchadh Ó Laoghaire, Seán Crowe and Réada Cronin. None said no. All four promised to return with a reply. None did.

Elisha McCallion, the deposed senator from Derry, forced to resign by Mary Lou in October 2020 over a funds scandal, initially said yes, but changed her mind within a few days, claiming that ‘the party is not linked into this project’. Elisha is former bomber Martina Anderson’s niece.

When I rang Deputy Pearse Doherty, he was in a hot snot over a piece I had written in the Sunday Independent about the Sinn Féin civil war raging in Derry. He said he wasn’t interested in the book.

The exercise was revealing. The non-combatants in the South were doing somersaults to fall into line with the ex-prisoners in the North.

Happily, as time passed, some initial naysayers quietly changed their minds and opened up. I spoke to former Sinn Féin ministers, MLAs and TDs. Others gave off-the-record briefings, while many who had left Sinn Féin in recent years came forward. I spent two hours at a secret venue talking to a former active member of the IRA’s Army Council, a household name.

My series of calls suggested that when there is a different agenda between North and South Sinn Féin, the demands of the Northern faction often prevail. Today’s Southern leaders, like Mary Lou McDonald, Pearse Doherty, Eoin Ó Broin, David Cullinane and Rose Conway-Walsh, have never seen action, while influential leaders in Northern Ireland are identified with the military wing. Some of the ex-army Sinn Féin leaders, such as Conor Murphy and Gerry Kelly, are now democratically elected MLAs but remain loyal to their past and to their actions. Gerry Adams had uniquely managed to straddle the military and political wings in order to speak for both the Northern and Southern Sinn Féin parties. Adams, a Northerner, led Sinn Féin in the Dáil while retaining supreme influence over the military wing in the North and South. Despite his protests that he was never in the IRA, nobody (except apparently Mary Lou) believes him.

When Mary Lou insists that the IRA has disbanded, it reassures her supporters in the Republic, but her influence over some elements north of the border is undoubtedly diminished as a result. While writing this book, I spent a great deal of time in Derry and Belfast discovering what politicians and people think of Mary Lou McDonald. Is she acceptable to Sinn Féin members as their leader, or is she a late arrival, a carpetbagger riding in on horseback for the endgame, hoping to clean up on the back of their struggle? Are the hard men of the North exploiting her? Is she merely a vehicle of convenience in the battle which they, not she, have fought for a united Ireland? Is her popularity and acceptability in the Republic their ticket to power when the two parts of Ireland come together?

It is equally important to discover how Ulster Unionists see her. Is she perceived as even more threatening to the union than Adams because she is poised to capture the office of Taoiseach in the Dáil while simultaneously holding the leadership of the largest political party in the Northern Ireland Assembly? Would they prefer Adams, the IRA devil they know from Belfast, or the less familiar woman from Dublin? Or does her distance from the Troubles make her more palatable to them?

Above all, there remains a more fundamental question about Mary Lou McDonald. Is she a true believer, a real republican or an adventurer, an opportunist, like many other politicians? Did she spot an opening for a young middle-class Southern woman in Sinn Féin over twenty years ago and go for the gap with gusto? Did she tailor her convictions accordingly? At first glance, her commitment to the republican cause seems shallow, even suspect. When Mary Lou is asked about her republican pedigree and convictions, she appears to be on tricky terrain. She invariably instances the hunger strikes in 1981 as her ‘road to Damascus moment’. Yet at the time of the IRA prison protests she was only twelve, a schoolgirl in Notre Dame des Missions school in suburban Dublin. Her insistence that the news of the prisoners’ deaths on the television screen were seminal events in her childhood is well known. Moreover, in an interview with Freya McClements of The Irish Times in April 2021, she boldly beefed up the imagery, painting a powerful picture of the effect on her family. ‘I remember,’ she said, ‘the day that Bobby Sands died. I can still see my brother running out to tell me, shouting the news . . . I was still a child and didn’t fully understand the politics of what was happening, but felt viscerally the fact that something was extraordinarily wrong in our country.’

It was undoubtedly a memorable moment in the life of the young Mary Lou, but strangely, ‘visceral’ or not, the memory seems to have lain festering, casually shelved for at least fifteen years. There is no recorded instance of her nursing or suppressing any dormant republican fervour or any remotely connected sense of injustice during her teenage years or as a university student. Her political passion was not woken from its slumbers until late into her twenties, after her marriage to Martin Lanigan in 1996, when she joined Fianna Fáil, the Irish National Congress and, finally, Sinn Féin in quick succession. During those missing years, the Troubles in Northern Ireland were raging, wrongs were being perpetrated on both sides, and the minority in the North was pleading for more support from sympathetic Irish men and women in the Republic. There were openings galore for nationalists, young and old, to promote the cause of a united Ireland. Mary Lou McDonald was at worst unconcerned, at best a ‘sneaking regarder’ of Irish unity, more energised at the time by urgent matters like her studies, her courtship with Martin and her social life. She was a normal student, determined to enjoy the experience, particularly in Notre Dame des Missions and in Trinity College Dublin, where she received a privileged education, undisturbed by high-minded ideological vocations like republicanism or social equality.

She backs up her ‘road to Damascus moment’ narrative with tales of her republican family background, citing both her mother’s and her father’s Fianna Fáil roots. This might explain her first political decision to join Fianna Fáil, but not the haste with which she left the party and switched to Sinn Féin. Her passage to the top of Sinn Féin at breakneck speed was highly unusual in a party building up from the grass roots in the early years of this century. She had bags of talent, but so did many other newcomers to the party at the time. They were forced to take the dreary county- or city-council route. Mary Lou was not.

If she was initially a political mongrel who transformed herself into a republican thoroughbred, her family life is a key component to understanding her political versatility. Critical commentators frequently dub her an ‘enigma’ because they have never been able to fathom how a charming girl from upmarket Rathgar made the jump over to what many of them consider the dark side. Some are horrified that such a thing could happen, but maybe they should start looking for answers in the obvious places. None of them have probed the impact on her of the two principal men in her home life: her father, Paddy McDonald, and her husband, Martin Lanigan. Nor have they sought to determine the influence of her mother, Joan, or her strong-minded sister, Joanne, or her other siblings. All we know is what Mary Lou has told us. Her own account of her early life is determined by a very powerful airbrush. It is supported by an even more powerful broad brush.

Mary Lou had an exceptionally supportive extended family network. She would come to need it. She had four aunts (sisters of her father), most living near her Rathgar home, who played a noble part in providing security and back-up during her childhood. On her mother's side, she had two married uncles with children, a farming family living in deepest Tipperary, where she spent most summer holidays. It is simplistic to put her later puzzling choice of political allegiance solely down to the charisma of Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness, or to a young idealistic woman’s failed experiment with Fianna Fáil causing her to flee into the arms of Sinn Féin.

Yet she did join and leave Fianna Fáil, the political party of both her parents, within little more than a year. Again, two different explanations of her short-term loyalty to Fianna Fáil have emerged. Most party members have maintained, until now, that she left Fianna Fáil because she was in a hurry, frustrated because her progress was being blocked by the late Brian Lenihan Junior. They insist that she felt Lenihan saw her as a threat rather than an asset in his Dublin West constituency. Others believe her own version: that Fianna Fáil was weak on the national question, that its members were not true republicans. So she switched horses.

Surprisingly, Mary Lou is not a fluent Irish speaker, a skill that might have been expected to be a priority for a nationalist with high aspirations. Nor is there any evidence that her sympathy for Northern nationalists was accompanied by, or based on, frequent visits to Northern Ireland in her youth.

She has always protected the men in her life from public scrutiny. Her carefully hidden father is an unpredictable character who might merit a biography in his own right. He fully earned the half-chapter he has been afforded in this book. Mary Lou has given him the full airbrush treatment.

Her husband, Martin Lanigan, the father of the couple’s two children, Iseult and Gerard, has been even less visible than Mary Lou’s father. He appears almost nowhere in public with her, which has prompted inevitable curiosity.

Her mother, Joan, is regularly wheeled out by Mary Lou with gratitude for being a stable force when her father was absent. Despite the disruption caused by her parents’ separation when Mary Lou was ten, she always doggedly insists that she had a happy childhood and that hers was a very close family. Presumably she excludes her severed father from the happy family unit but, when pressed, says that she loves him. His compulsive recklessness before and after his separation from Joan cannot have aided the cause of a happy upbringing for their four children. According to Mary Lou, her mother was not an active republican but supported ‘Amnesty International and was very involved in the Burma Action Group’. She worked as a teacher and in a medical centre after the children were reared.

Her younger sister Joanne’s mysterious membership of a far more militant republican socialist group than Sinn Féin has never before been properly explored. Mary Lou has openly declared her closeness to Joanne and her children. She never discusses her sister’s unconventional republican activities. They too receive the overworked airbrush.

Mary Lou McDonald’s skilfully spun narrative of her early years is the story of a highly conventional education and childhood. She rattles off the CV of a girl from Rathgar who attended a private convent, followed by obtaining a degree from Trinity College, spending a postgraduate year in Limerick and working a few short-term, humdrum jobs. A pretty ordinary middle-class biography. Hence the surprise that she opted for Sinn Féin, the party currently associated with rebels and underdogs.

Mary Lou’s early life and activities do not sit comfortably with her political destination. The unvarnished truth is far from this almost universally accepted, but unchallenged, version of her life before politics, which is hopelessly incomplete, with many aspects of her background and political activities hitherto unexplored and unexplained.

The road that may lead her to the Taoiseach’s office is littered with riddles. The IRA riddle and her real relationships with the military wing of Sinn Féin is only one conundrum in the story of this complex woman’s rise to the top.

CHAPTER 1

THE SKELETON IN THE CUPBOARD

Mary Lou McDonald’s father, Patrick ‘Paddy’ McDonald, was no angel. He married Joan Hayes on 3 April 1967. The wedding took place in the Roman Catholic church in Monkstown, County Dublin, five days before Joan’s twenty-first birthday. Paddy was only twenty-three. Their first child, Beatrice (Bea), was born on 31 August 1967. She was designated male at birth and confirmed her transition in 2021. Her sister Mary Lou was born on May Day 1969 in the National Maternity Hospital in Dublin’s Holles Street.

Mary Lou has always portrayed her mother as an unsung saint. The two pivotal figures in her early life could not have lived more different lifestyles. Paddy was wild, Joan a rock of common sense. Both are still alive.

Researching this book, I have met gardaí who arrested Paddy, lawyers who defended him and publicans who loved him. Mary Lou’s father is what is often euphemistically called a ‘character’. He has left a trail of trouble wherever he trod. Some of those he has met along the way describe him as a daredevil, others as a lovable rogue; a number mutter unprintable expletives under their breath. Mary Lou prefers not to talk about him.

Paddy was reared in middle-class Rathmines by his parents, Bernard and Annie. He had four older sisters, Maeve, Nora, Joan and Phyllis. Maeve, the oldest, died in February 2022, while Phyllis, the youngest, predeceased her in December 2019. The surviving aunts of Mary Lou speak of their niece with great fondness. They are, understandably, more reticent, but equally affectionate, when their wayward brother’s name is mentioned.

Paddy started his working life as a small building contractor, following in his father’s footsteps. He entered the workforce in his teens and had already built his first house when he was twenty-one. Business was buzzing in the early years of his marriage. He saved money and made a profit of £5000 in the first six months of 1970. He, Joan and their two children lived in comfortable rented accommodation in Eaton Brae, Rathgar, a slightly higher rung up the south Dublin social climbers’ ladder than his former Rathmines homestead. The McDonalds were upwardly mobile. Paddy’s progress was not hindered by his Fianna Fáil contacts or, more pointedly, by his membership of the party of builders and strokers. He played rugby for Palmerston. Kevin Fitzpatrick, former president of the club, remembers him as a ‘rough diamond. He was a prop forward, a square-jawed man; he could be very funny. He was in and out of the first team.’

Mary Lou was barely a year old when, on a summer night in 1970, Paddy’s world collapsed. Her father was a passenger in the back of a Volkswagen that was involved in a head-on crash. The accident nearly killed him. It was around midnight when he saw the approaching headlights, as the Volkswagen tried to overtake another car. His next memory is nearly twenty-four hours later. He regained consciousness in the Meath Hospital, hearing the voices of his wife and his sister Phyllis by his bedside. He learned that he had been hurled through the windscreen. A priest had given him the last rites. Mary Lou was nearly fatherless at the age of one. Her mother, Joan, escaped widowhood by a whisker.

In November 1985 Paddy told Magill magazine that he had suffered multiple life-changing injuries in the crash. His back and neck were badly damaged. But, like many self-employed people, he needed to return to work rapidly. He had a wife and two children to support and a valuable countrywide contract with Telefusion (Ireland) to fulfil. Ten days after the crash he was back on the job.

Life for Paddy would never be the same again. The injuries he had suffered caused him to feel dizzy at work. He could no longer climb up poles or crawl along roofs because of the vertigo he would suffer. He was unable to monitor the activities of his workforce. He under-priced jobs, something he had never done before his mishap, and lost all confidence in his ability to function effectively. Despite medical treatment and physiotherapy, after two months he began to realise that his health was not improving, and so his livelihood was threatened. He decided to go down the compensation route.

An employee of Paddy’s steered him into the arms of a lawyer called Brendan O’Maoileoin of Michael B. O’Maoileoin Solicitors, an introduction Paddy would rue in the years to come.

Brendan O’Maoileoin was even more ‘colourful’ than Paddy. He was a former member of the Fianna Fáil national executive and a two-time candidate for the Seanad. He lost his seat on the national executive in 1970 and was easily defeated in his Seanad bids on both occasions. He lived in a grand-sounding house in Dundrum named Altamont Hall and sent his sons to Stonyhurst, the upmarket English Roman Catholic public school. He was later to become embroiled in a row at Dublin’s United Arts Club when he was expelled for ‘behaviour unbecoming of a member’. He sniffed snuff and drank plenty.

Paddy told Magill that, owing to his injuries, he had decided to stop working on site. O’Maoileoin was confident of a satisfactory outcome to the compensation claim, but advised waiting until both drivers in the accident had faced pending prosecutions. It seemed a wise course to take, although it meant that Joan, Bea and Mary Lou were now surviving on Paddy’s savings. In 1971, all criminal actions surrounding the crash were completed, so Paddy’s compensation case was poised to commence. According to Paddy, he restarted his business, although he himself was physically incapable of participating actively in it.

It was a bad decision. The business staggered from month to month. Paddy, wary of ladders, was unable to supervise most of the work. Jobs went wrong with regularity. Paddy felt that his workers were exploiting his inability to climb on to the roofs to monitor their activities. At the same time, the preferred solution – a chunky compensation award – seemed, strangely, to have stalled. O’Maoileoin was suspiciously busy when Paddy McDonald came calling. The optimistic Fianna Fáil lawyer seemed to be ducking and diving.

Legal proceedings were moving tortuously slowly. They dragged on into 1973, with no explanation for the delay. Three years after the accident, Paddy had not been awarded a red cent. It was the year that he and Joan were blessed with twins, Joanne and Patrick, born on Hallowe’en day. Suddenly Paddy had six mouths to feed. He was finding it difficult to support his wife and children.

Around this time brushes with the law began happening to Paddy with alarming frequency. Drink was an ever-growing menace. His troubles were coming in big battalions. Never a man to abstain from alcohol, he landed himself in embarrassing scrapes.

While researching Mary Lou’s family history, I met a garda who had arrested a sozzled Paddy over fifty years ago for the relatively minor offence of refusing to get off a bus in Rathmines. It was Christmas Eve and Paddy was blotto. The garda put him in a cell and left him to cool off while he resumed his patrol. When he returned at around 2.30 in the morning, Paddy was out of the cell haranguing the puzzled duty sergeant. The garda who had arrested Paddy told me a bit about him, his Fianna Fáil connections and that he ‘drove an old van and was in the building business’. Because it was Christmas Eve, the guards let him go.

On 28 February 1973, the day of the general election, Paddy landed in a spectacular scrape. He was a loyal and loud Fianna Fáil supporter, specifically working for candidates Philip Brady, Ben Briscoe and Gerard Buchanan in the constituency of Dublin South-Central. Paddy drove a truck carrying the Fianna Fáil posters around the constituency. After parking it illegally near the Harold’s Cross dog track on election night, he defiantly got back into the truck when a tow-away vehicle arrived to take it to the compound. A row broke out. Paddy refused to remove himself to allow the truck to be taken away. The truck, the posters and Paddy all ended up locked in the corporation compound.

The following day – 1 March 1973 – the Irish Independent, tongue-in-cheek, told the story, together with a large picture of the truck, the offending posters and the bold Paddy, embedded in the driving seat. Headed ‘The Van behind the Wire’, the story read:

Fianna Fáil’s drive to get its supporters out to vote in the Dublin South-Central Constituency was blunted last night . . . by a vigilant traffic warden.

He spotted a large van festooned with posters of the three candidates, Ben Briscoe, Phil Brady and Gerard Buchanan parked in a rush-hour clearway and promptly called in the tow-away vehicle.

It did not go down very well with the party’s supporters who saw their well-oiled election operation being disrupted at a vital time.

As the tow vehicle edged its way towards the van at Harold’s Cross Road about forty people protested.

But the law had its way, and off the van was taken to the Corporation compound at Christ Church Place where it became briefly the ‘van behind the wire’.

However, within minutes of its capture Fianna Fáil workers were bailing it out and it was soon making its way once again around the constituency.

Forty years later, Mary Lou McDonald aped her father’s election-eve drama when, not only did she refuse to leave the Dáil when suspended, she also implanted herself in the chamber itself for several hours, challenging the ushers to remove her physically. She brought Dáil proceedings to a close. Both acts of defiance escaped unpunished.

Paddy and his candidates had the last laugh. Both Brady and Briscoe were elected. Gerry Buchanan was beaten but was appointed a judge a few years later.

During 1973, things went from bad to worse for Paddy McDonald. He was still receiving physiotherapy and medical treatment for the accident. His business was in free fall. In 1974 his money ran out. Further inexplicable delays in the legal case were causing him huge stress. So were the Montessori school fees for Bea and Mary Lou. Paddy, full of bravado, regaled his pals in the pub with cock-and-bull stories of how he had tossed a coin with the school principal for the kids’ nursery school fees. His savings spent, Paddy borrowed from the bank.

The business was limping from one disaster to another. He still had a few hard-won Eastern Health Board contracts and a job at the Dundrum mental hospital, but even they went wrong as his physical health failed to improve, despite medication.

O’Maoileoin became even more elusive. He made excuses for delaying appointments; he was never available. Paradoxically, according to Paddy, the two men remained on good terms, exchanging stories about Fianna Fáil friends on the rare occasions when they actually managed to meet. In one instance, O’Maoileoin had given McDonald a solicitor’s undertaking as comfort for a bank loan. He used the money borrowed on the back of this promise to tackle a job in Arklow. It was never finished. He wasn’t paid.

While Paddy McDonald was sinking, Brendan O’Maoileoin was flying: he had moved to a newly renovated office in Dublin’s Lower Fitzwilliam Street. Paddy’s visits to him became less friendly, but more frequent and frenetic. Paddy was calling every day; the temperature was rising. On one occasion, he became involved in an altercation with the receptionist when he tried to leave the office with his file. The endless delays continued, defying explanation.

As Paddy tells it, he was beginning to flounder in 1975. He could not sleep and he was taking Mogadon in increasing quantities. He was receiving treatment from a top psychiatrist. His marriage was in danger and he was drinking like a fish.

Just as Paddy thought he might crack up, a meeting was arranged with O’Maoileoin and his barristers in the Four Courts. Paddy recalls a mention from the lawyers of an offer of a £3000 settlement, but he told them of the scale of his personal incapacity, that he needed more than £30,000, considering his permanent state of ill health, his four children and the loss of his normal working-life expectancy. His senior counsel reassured him that he would get him ‘a fair settlement’, but warned him that the taxman would take a big slice of any notional £30,000 award.

Paddy McDonald didn’t give a hoot about the taxman. He would deal with him in due course. He was now desperate for money; he didn’t even have the cash for his bus fares. He couldn’t pay the rent on the family apartment for Joan, Mary Lou and her siblings. He hassled and harried O’Maoileoin to no avail, until his faith in his solicitor was finally shattered. He even considered, in his own words, ‘doing away with O’Maoileoin’.

Drink was landing him in more trouble. In early 1976, he was back in court, this time for all the wrong reasons. On 17 February, the Evening Echo, a Cork newspaper, and the Irish Independent both carried a story about an excitable neighbour of the Russian Embassy, on Dublin’s Orwell Road, storming into the high-security citadel in the early hours of the morning. This time, Paddy McDonald was in hot water.

Headed ‘Russia Embassy parties keep children awake’, the Evening Echo’s narrative ran as follows:

Late night parties in the Russian Embassy in Dublin keep young children in the neighbourhood awake until the early hours, an accused man claimed at a Dublin court yesterday.

He went to the Embassy to lodge a complaint but was surrounded by ‘six KGB men’ after he had thrown a length of rubber at an official inside the grounds, he told Justice T.P. O’Reilly at Rathfarnham Court.

Before the Justice was Patrick McDonald, a building contractor of Ard na Gréine, Eaton Brae, Orwell Road, Rathgar. He was charged that between 1 and 2 a.m. on August 28 last at Orwell Road – a public place – he was guilty of disorderly behaviour while drunk.

He was also charged that on the same occasion he used insulting words or behaviour with intent to provoke a breach of the peace or whereby a breach of the peace might be caused. McDonald, who defended himself, disputed the first charge by pointing out that the offence of being drunk was not committed in a public place but within the grounds of the Russian Embassy, a place where the general public have no access. This charge was dismissed.

Dealing with the second charge, Justice O’Reilly asked McDonald could he show cause as to why he should not bind him to keep the peace.

The defendant said his house was only a very short distance from the Embassy on Orwell Road. His four young children, he said, could not sleep because of the ‘constant parties being held in the Embassy’.

The disturbances were so bad on this particular night that he decided he would have to do something to rectify the matter. He approached the Embassy lodge and knocked on the door but got no reply. Then he walked up the driveway to the Embassy itself. He tried to explain the point to an official – ‘but this man only laughed at me.’

McDonald added; ‘I took up a piece of rubber and threw it at him and almost immediately was surrounded by six KGB men.’

He was very glad when the Gardaí arrived.

Inspector Thomas Noone, prosecuting, said the Gardaí had never received any complaints from residents about disturbances at the Embassy – even though there were a number of families with young children in the neighbourhood. If the defendant wanted to complain, he could have phoned the Gardaí, who would have handled the matter for him.

Justice O’Reilly also dismissed the charge and made no order binding to the peace after McDonald gave an undertaking that there would be no repetition of his conduct in the Embassy grounds.

The Irish Independent’s account was even more colourful. At the top of page 3, it entitled its piece ‘Saw Red at the Russian Embassy’. It told of how McDonald ‘blew his top’ about ‘Russian high-jinks’ and how Garda Aubrey Steedman added that Paddy had been ‘shouting about the KGB and seemed to want to be arrested’. He also appeared to have had ‘drink taken’.

Garda Steedman wouldn’t have needed to consult the Special Branch to come to that conclusion.

Paddy McDonald gave an assurance to the court that he would not repeat his behaviour and he walked away an innocent man.

The episode illustrated that while Paddy McDonald was often a drunken buffoon, he was nobody’s fool; he had spotted that his offence was not committed in a ‘public place’, as written on the charge sheet. The Russian Embassy was the opposite: it was a private fortress which he had penetrated. He secured his own acquittal without the need for expensive lawyers. No doubt he entertained punters in the pub for months afterwards with tales of how he had outwitted the KGB and the gardaí. He had no fear of the courts. McDonald was to spend much of the next decade fighting his corner in front of the beaks.

The court merry-go-round began in earnest in 1977, seven years after the car crash. Mary Lou was by then an eight-year-old and, although she has spoken little of her home life during this period, it must have seemed far from stable, even through the eyes of such a young child. According to Paddy, his marriage was now in deep trouble, but he had talked to Joan about buying a small shop with the compensation money which, he claimed, would enable him to support his family again. But his personal crisis deepened and he began to behave increasingly recklessly. Paddy says he was told that the court had awarded him ‘hardship’ money until the compensation case was settled, so, even though he no longer trusted the word of his own lawyers, desperate, he accepted a cheque from O’Maoileoin for £1,100. He went straight to a Rathmines bank to cash it, only to find that it was crossed and would have to go through an account, impossible before closing time on a bank holiday weekend. He stormed back to O’Maoileoin’s office in a rage. His solicitor capitulated and arranged for it to be cashed before the bank’s doors closed that day.

The court case was held the next week. Marcus Webb, an eminent psychiatrist who specialised in alcohol dependence, was there. So was Derek Robinson, a Meath surgeon, presumably to give evidence about the car accident. There was an accountant, Donal Ward, Paddy McDonald’s GP Dr Berber, two senior counsel, one junior counsel and O’Maoileoin.

Paddy McDonald was puzzled. The senior counsel were not the ones he had expected. He had demanded a hearing before judge and jury, but had been willing to settle the case if a realistic sum was offered, at least enough to set him up in a business to support his family.

Soon after his senior counsel opened the case, it was adjourned. When it resumed, none of the counsel or other potential professional witnesses were present. Just McDonald, O’Maoileoin and the junior barrister.

Then the bombshell dropped. O’Maoileoin took the stand and revealed that the compensation case had been settled in 1975, two years earlier. Paddy McDonald had been kept in the dark; he promptly told the court that the lawyers had settled the case without his authority. He remembered only the £1,100 cheque, which he had understood was ‘hardship’ money to tide him over until a settlement was reached. He was shattered, emerging from the court dazed, his hopes of a rescue package dashed.

The court had told him that it was open to him to pursue O’Maoileoin for negligence, not misconduct.

O’Maoileoin vanished into thin air. Paddy went home that night devastated. According to his own account, his wife Joan asked what hope there was now for her, Bea, Mary Lou, Patrick and Joanne. The settlement money was a pipe dream. The family had no future. Seemingly, O’Maoileoin had ruined them.

Paddy McDonald may have been an incorrigible and battered rogue, but he refused to give up. Although it was almost impossible in those days to find a solicitor willing to sue a fellow lawyer, he resolved to try. For once he was lucky. Through his Fianna Fáil connections, he knew John Fitzpatrick, a highly respected solicitor with Vincent & Beatty, a reputable firm. John Fitzpatrick took on the case, a decision that probably did not endear him to his peers, but it was a courageous call by a man of integrity. Fitzpatrick was later to be Dublin City sheriff and returning officer for Dublin City constituencies.

The pursuit of O’Maoileoin began. Paddy McDonald headed back to the High Court. This time he had a team of heavy-weight lawyers in good standing with their peers. Nicholas Kearns, a senior counsel with a high reputation, advised the team assembled by John Fitzpatrick. (Kearns was later to become a supporter of the Progressive Democrats and president of the High Court.) Nevertheless, there were further delays; it took months to access Paddy’s file, eventually achieved with the help of an unnamed Fianna Fáil politician.

Paddy McDonald’s marriage to Joan had finally cracked under the strain. In 1979 they separated when he moved out of the family home, leaving Joan to bring up Mary Lou, aged ten, and her three siblings on her own.

Undeterred, Paddy soldiered on. He was finally back in court in 1980, running an action to establish negligence against O’Maoileoin and another for damages. The High Court found in his favour, adjudging O’Maoileoin to have been negligent. O’Maoileoin appealed the decision to the Supreme Court. On 11 March 1982 The Irish Times carried the result of the appeal:

Court rejects appeal by Dublin solicitor

The Supreme Court yesterday dismissed with costs an appeal by a Dublin solicitor against a finding by a jury in the High Court that he had settled a personal injuries action without the authority of his client.

The appellant was Michael B. O’Maoileoin, who carries on practice as a solicitor at Lower Fitzwilliam Street, Dublin and against whom an action was brought by Patrick McDonald, a building contractor, Eaton Brae, Orwell Road, Dublin.

Mr. McDonald claimed that he retained Mr. O’Maoileoin to act for him in an action for damages for personal injuries and that Mr. O’Maoileoin, without his authority, settled the action for £4,250 and costs in 1976.

The court was told that Mr. McDonald refused to accept the settlement and had insisted that his action should proceed. When the action came up for trial, the defendants claimed that it had been settled. An issue was directed as to whether, or not, the action had been settled and the President of the High Court (Mr. Justice Finlay) held that it had.

Mr. McDonald then brought proceedings against Mr. O’Maoileoin, and another issue was directed as to whether Mr. O’Maoileoin had settled the case without authority. This was tried before Mr. Justice D’Arcy and the jury found in Mr. McDonald’s favour.

The Chief Justice (Mr. Justice O’Higgins) said that the basis of the appeal was that on the evidence given before the jury only one answer could be given to the question as to whether Mr. O’Maoileoin had settled without authority, express or implied. It had been submitted on Mr. O’Maoileoin’s behalf that an affirmative answer by the jury was perverse.

The judgement was plain sailing in Paddy McDonald’s favour, but there was a sting in the tail. The chief justice had some harsh words to say about his evidence. The article went on:

The Chief Justice asserted that the evidence of Mr. McDonald left much to be desired; it appeared at times to be unreliable. It appeared at times to be impossible to accept in certain particulars, but consistently throughout his evidence was the assertion that he had given no authority for the acceptance of the sum.

He would dismiss the appeal. Mr. Justice Henchy, who agreed with the Chief Justice, said the accident had happened in 1970 and it was now 1982. A great part of Mr. McDonald’s life would have been spent in one form of litigation or another. All this seemed to be inconsistent with the due administration of justice. If damages were to be determined – as they would – on what basis could they be determined? Since 1970 inflation had driven all concepts of money topsy-turvy and he could not see how any jury in 1982 or 1983, as it might be, could assess damages now when the real time for assessing damages should have been in 1975 or 1976.

It was within the competence of the jury, he said, to decide that the limit of Mr. O’Maoileoin’s instructions was to proceed with the negotiations, but not to settle without the imprimatur of the client. That was what they had found.

Mr. Justice Griffin, who also said he would dismiss the [i.e. O’Maoileoin’s] appeal, said the court was not entitled to interfere with this finding. It seemed to him that Mr. McDonald would be entitled to such damages as he would have recovered in 1976, not in 1983.

The exact compensation remained unsettled until 1985 when the amounts were finally decided by the High Court. Paddy McDonald was awarded £15,000 damages and £12,000 special damages to include loss of earnings. On top of that he was awarded £22,780 for interest and costs.