Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

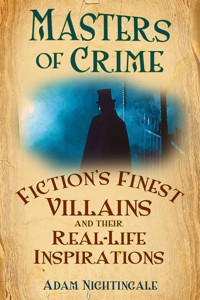

This fascinating volume reveals the real men – and women – behind some of the most infamous London villains ever to appear in fiction. Fagin, Professor Moriarty, Moll Cutpurse and the notorious 'cracksman' A.J. Raffles were all rooted in the lives and deaths of a litany of real-life criminals, agitators and activists. With a special emphasis on the city that spawned them, this book brings together their stories for the first time, and shows how they were woven into fiction by some of Britain's greatest writers, including Charles Dickens and Arthur Conan Doyle. Containing prison escapes, sensational trials, daring art thefts, vicious attacks, roaring boys, black magicians and private detectives, Masters of Crime explores both the real underworld of British crime history, and its fictional counter-parts. It will delight fans of true crime and crime fiction alike.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 340

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Simon Hammond. ‘I shot him six times.’

‘I knew not what wild beast we were about to hunt down in the dark jungle of criminal London, but I was well assured, from the bearing of this master huntsman, that the adventure was a most grave one …’

The Empty House, Arthur Conan Doyle

First published 2011

The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2016

All rights reserved © Adam Nightingale 2011

The right of Adam Nightingale to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced. transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8133 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Part One: The Building Blocks of Master Villainy

1 The Great Feud

2 The Great Feud: In Print

Part Two: Sundry Master Villains & One Villainess

3 A Notorious Baggage

4 Two ’Spectable Old Gentlemen

5 The Man Who Killed Sherlock Holmes

6 Little Adam & The Eye

7 Feasting with Panthers

8 The Wickedest Man in the World

Notes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Pete Nightingale, Susannah Nightingale, Alec and Jo Cobb, Matt and Louise Frost, Gio Baffa, Pollie Shorthouse, Bev Baker, the staff of the Galleries of Justice Museum of Crime and Punishment, Paul Baker, Maureen from Towncentric – Gravesend Tourist Information Centre, Micah Harris and Max Allen Collins.

PART ONE:

THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF MASTER VILLAINY

1

THE GREAT FEUD

‘Have you read of Jonathan Wild?’

‘Well, the name has a familiar sound. Someone in a novel, was he not? I don’t take much stock of detectives in novels – chaps that do things and never let you see them do them. That’s just inspiration, not business.’

‘Jonathan Wild wasn’t in a novel. He was a master criminal and he lived last century.’

‘Then he’s no use to me. I’m a practical man.’

The Valley of Fear, Arthur Conan Doyle

WILD

On 31 March 1716, mother and son John and Mary Knapp were attacked by a gang of five men whilst returning from an evening at Sadler’s Wells. John Knapp was knocked to the ground and the thieves took his hat and wig. Mary Knapp shouted for help. One of the gang members produced a pistol and shot her dead. A reward was immediately posted for the attackers’ capture.

The gang comprised Thomas Thurland, John Chapman, Timothy Dun, Isaac Rag and William White (the murderer). On 8 April, barely a week after the crime had been committed, William White was drinking and whoring at the home of a friend in Newtoners Lane. Two men arrived at the house. One was short and wiry and spoke with a West Midlands accent; the other was a Jew. The two men subdued White and took him to the Roundhouse to be locked up. The West Midlander was Jonathan Wild, the self-proclaimed Thief Taker General of Great Britain and Ireland. His companion was Abraham Mendez, Wild’s tough and loyal sergeant-at-arms and first among equals of the many self-styled law enforcers at the Thief Taker General’s beck and call. Soon after, Thurland and Chapman joined White on the gallows. Isaac Rag was captured but spared Tyburn and put in the pillory instead after informing on twenty-two of his fellow thieves. All four men had been hunted down by Wild and his associates in a very short space of time. Only Timothy Dun was still at large.

Abraham Mendez shoots Timothy Dun while he is trying to escape. (Illustrated by Stephen Dennis)

Dun had gone into hiding. Wild was confident that given a little time Dun would surface and give himself away. He had even placed a bet of 10 guineas that he would have Dun in custody before the next court sessions. Dun, for his part, was wondering whether in fact the impetus to catch him had subsided. Most of the gang had been caught and, more importantly, the murderer had been executed. Dun sent his wife to approach Wild personally and test the water as to the exact nature of his current fugitive status. It was a bold move and risky on Dun’s part, but his wife was cautious and took extra care to make sure that none of Wild’s men tried to follow her. She took an elaborate route back to her husband, criss-crossing the Thames and finally ending up in Lambeth, before she was confident that she had done enough to shake off any tracker Wild may have dispatched to tail her. She then returned to Dun’s hideout in Southwark.

Wild’s men were much more skilful than Dun’s wife had anticipated. She had been successfully followed and her house had been marked with chalk. Wild arrived in the morning with Abraham Mendez, a Mr Riddleson and an unnamed man. Dun heard Wild approach and he tried to make his escape out of the back window, two floors above street level and 8ft from the ground. Mendez spotted him and shot him in the arm, causing Dun to fall to the ground. Riddleson then shot him in the face. Dun survived his two gunshot wounds, but was subsequently tried and hanged.

A violent and murderous gang had been permanently broken up by the industry and courage of Jonathan Wild and his small army of amateur law enforcers. Wild hadn’t done it for free. The rewards posted for the gang’s capture would have been substantial, but in an extremely violent city, where official methods of policing were woefully unequal to the task, Wild’s name was synonymous to many with justice. By 1725, Wild could boast of having been responsible for hanging in excess of sixty criminals. He had twice had his skull fractured, had received numerous wounds and wore an ugly scar where his throat had been slashed – all physical tokens of his devotion to civil order. But others knew better. In actuality, Wild’s activities were a highly mercenary and sophisticated smokescreen masking a vast criminal empire that regulated the movements and activities of virtually every criminal in London. Wild was the first English crime baron. His exploits, when finally exposed, would scandalise his peers and provide the archetypal example for satirists, novelists, playwrights, journalists and crime writers to draw on for generations to come.

Under the guise of the Thief Taker General of Great Britain and Ireland, Jonathan Wild hunted down any criminal that refused to do business with him. (The Chronicles of Crime, Vol. I, T. Miles & Co., 1891)

Jonathan Wild was born in Wolverhampton around 1683, although the exact date of his birth is not known. His father was either a wig-maker or a carpenter whilst his mother was a market trader. For his class and social station, Jonathan Wild was well educated. By the age of 15 he could read, write, was numerate and had been apprenticed to a buckle-maker. By 19 he had married and by 20 he had fathered a son. A year later he had abandoned them both and travelled to London.

The London of the early eighteenth century was vicious, overcrowded, squalid, wealthy and tantalising. The chasm between luxury and poverty was enormous. The systems of law enforcement that relied on constables and nightwatchmen to patrol a London divided and subdivided by archaic parish borders was swamped by the sudden and massive surge in the population. London arguably became the most lawless it had ever been in its entire history. It was a deeply licentious place and irresistible to Jonathan Wild.

Wild worked at being a buckle-maker only for a short period of time. His lifestyle was profligate and his earnings couldn’t keep pace with his appetites. He was arrested for debt and thrown into the Wood Street Compter, where he served four years. Imprisonment was difficult for Wild. Wood Street was split into two sides: one relatively comfortable; the other harsh and disgusting. Where you were placed was entirely dependent on what you could afford to pay the authorities. Jonathan Wild had no money and no friends willing or rich enough to subsidise him. Lack of funds therefore consigned him to the Common Side of the Compter and Wild was forced to fend for himself.

Yet Wild survived. In time he won the confidence of the gaoler and he was given a job helping the gaoler to manage prisoners brought in during the night, ferrying them back and forth between the Justices of the Peace and the Compter. In this capacity, Wild met Mary Miliner. As one of the most notorious pickpockets and prostitutes of the era, Miliner was shrewd, tough and well connected. She would become the first of two mentors that schooled Wild thoroughly in the workings of the London underworld. He would outgrow both of them, assimilating and superseding anything that they could teach him, leaving one of them permanently disfigured and the other a ruin. All of that was to come, but for the time being Wild was the perfect student. Miliner paid off his debt and he went to work for her.

Initially, Wild and Miliner got on very well. They became lovers and lived together as man and wife. Wild worked as Miliner’s ‘Twang’, Georgian slang for a prostitute’s thug, bodyguard, protector or pimp. But the word pimp in this context is misleading; Miliner was the boss and Wild’s principal function was as a participant in a humiliating and brutal form of theft. Miliner would pick up a client, have sex with him, while Wild robbed him at his most distracted and vulnerable.

Wild was a consummate observer. In Wood Street he had watched and learned how a certain level of the thieving classes operated, mentally processing the information and secretly devising ways in which their various methodologies could be refined and improved. Under Mary Miliner a whole new strata of criminal life was open to him. Mary introduced Wild to much of the city’s criminal royalty. Wild got to know the capital’s divers gangs, their operations and their hideouts. He realised very quickly that intelligence was artillery and stored the information away for a time when it might come in handy.

In the meantime, Wild and Miliner prospered. They established a brothel and bought an alehouse in Cripplegate that also doubled as a brothel. Wild had something of a genius for nefarious administration and would organise and direct the gangs of thieves affiliated with Milliner, sending them out to steal and co-ordinating their actions, making a point of never personally going with them or directly participating in a crime. He was extremely good at what he did. The gangs greatly respected his powers of organisation and Wild and Miliner made even more money, but Wild was beginning to outgrow Miliner. Their relationship soured irreparably when an argument ended with Wild reaching for a sword and hacking off one of Miliner’s ears. The couple parted ways shortly afterwards. Wild paid Miliner a weekly gratuity for as long as she lived, but he was done with her. Wild gravitated toward his second mentor.

Charles Hitchin was the under-marshal of Newgate Gaol. In effect, he was one of the city’s principal law enforcers, with men under his command and powers of arrest. In reality he was utterly corrupt. Having bought his rank and title for £700, he exploited it ruthlessly for financial gain. He was dandified in appearance and loved the attention of the public. From Wild’s point of view, Hitchin was much better connected than Mary Miliner, having 2,000 or so criminal affiliates to exploit or work alongside. Hitchin’s main source of income lay in fencing stolen goods, a profession Wild took to with enthusiasm and would reform to the point of fine art. Wild had fenced goods successfully for Miliner and had shown a greater interest and aptitude for that part of her enterprise than he ever did as her ‘twang’.

The fencing profession needed a radical shake-up. Before Wild had ever set foot in London, the art of receiving stolen goods had been dealt an almost fatal blow. Between 1691 and 1706 radical changes had been made in the law and anybody caught buying or selling stolen goods could now be branded, transported for fourteen years or even hanged. Thieves still stole but there were fewer professionals to take their goods to. And those receivers that were still in the profession charged thieves exorbitant fees for their services, to mitigate the increased penalties imposed by the law. Charles Hitchin was one of the few men who still consistently operated as a receiver.

Wild had been experimenting, overhauling the receiver profession under Miliner with great success, and he now brought his ideas to Hitchin. Wild’s innovation was to establish a system by which he would sell stolen objects back to the victims, having orchestrated the theft in the first place. Shortly after the theft had taken place, Wild (under the guise of a concerned civic-minded citizen) would apply to the victim stating that he knew a man that had come upon some items he believed might have been stolen and that some of the said victim’s belongings might be among them. Wild would explain that he might be able to get some of these stolen items back and would ask for a list of the missing belongings. He would extract a promise from the victim that he would take no action against his friend for failing to apprehend the thieves, and he would convey that a reward for his friend would not be an imprudent thing, either.

The victim would generally go along with the proposal. The advantages would be that they would get their goods back and be spared the unpleasantness and cost of having to take the thieves to court (prosecutions being generally funded by the victim). Wild would arrange the meeting, the victim would meet Wild’s middleman, money would change hands and the stolen goods would find their way back to the victim. Wild would refuse any reward offered to him personally and when the victim was gone the money would be divided proportionately between all concerned. Wild (and presumably Hitchin) would take the lion’s share of the money, but the thieves still stood to make much more than they ever did under the old system (the money people were willing to pay to get their property back being sometimes half the actual value of the stolen objects). It was an adaptable system. Generally, the thefts would be at Wild’s command and the stolen items would be stored in a warehouse. But if an unsolicited theft or burglary had taken place, it wasn’t difficult to track the thief down and intimidate them into doing business Wild’s way. Wild even had a strategy for dealing with suspicious victims who correctly suspected that Wild might be complicit in the theft. When challenged, Wild would feign offence and take the insinuation as a direct affront to his honour. He would storm off, and if the victim didn’t call him back, Wild’s parting shot would be to tell him where he could find him if he ever changed his mind. They generally did, and Wild’s reputation amongst respectable society as the man to go to if you had been robbed began to grow.

Wild’s system met with the general approbation of the criminal community. Wild was seen as intelligent, organised, tough and ruthless enough to command their respect, but generally fair to those who did business with him. He was emerging as a natural leader, whereas Hitchin was vain and markedly less intelligent than Wild. Jonathan stuck with Hitchin for two years and then set up on his own. Hitchin would have been wise to do business with Wild and accept the shift in the balance of power, but Hitchin had effectively been the cock-of-the-walk for far too long to accept what he saw as the usurpation of his position. So Hitchin went to war with Wild.

Wild vs Hitchin was a strange and polite gang war fought using pamphlets and the gutter press, the consequences of which, for the loser, would be as brutal as if guns and knives had been the weapons of choice. In 1718 Hitchin circulated a pamphlet entitled The Regulator; or a Discovery of Thieves, Thief-Takers & co. In it he accused Wild of applying his buckle-making skills to forgery, working as a twang, recruiting prostitutes for the purpose of training them as thieves and operating as a receiver of stolen goods. He called Wild the ‘Captain-general of the army of plunderers and Ambassador Extraordinary from the Prince of the Air’ – ‘Prince of the Air’ being one of the names given to the devil in the Bible. Most of what Hitchin had said about Wild was true, but everything that was true of Wild was mainly also true of Hitchin, with one damaging exception. Charles Hitchin was a homosexual and a prominent customer of London’s gay brothels (or Molly Houses). He had even taken Wild to a Molly House when the balance of criminal power had seemed to favour Hitchin. And this was the basis of Wild’s retaliation. Wild’s pamphlet answered the charges levelled against him but the main focus of his attack was an exposé of Hitchin’s sexual practices. Wild described his own visit to the Molly House with his benefactor, emphasising Hitchin’s clear knowledge of the scene (Hitchin being referred to as ‘Madam’ and ‘Ladyship’ by many of the prostitutes). Wild assumed a tone of mock servility:

I’ll take care that no woman of the town shall walk the streets or bawdy house be kept without your Excellencies licence and trial of the ware; that no sodomitish activity shall be held without your Excellencies and making choice for your own use, in order which I’ll find a female dress for your Excellency much finer than what your Excellency has been hitherto accustomed to wear …

Wild called Hitchin ‘that cowardly lump of scandal’. He ended his pamphlet with a challenge to the public to test his integrity as the true, honest alternative to Hitchin, playing on the Georgian public’s fear and hatred of homosexuality. What must have been an open secret had not been used as a weapon against Hitchin before, presumably because up until that point he had been too dangerous to move against. Wild was now in a position powerful enough to expose him without fear of consequences. He effectively destroyed Hitchin. Charles Hitchin was now a spent force in the underworld. His eventual end would come nine years later when he was convicted of attempted sodomy and sentenced to a £20 fine, six months in gaol and one hour in the pillory. The public were permitted to throw things at whoever was in the pillory. Generally, the projectiles were rotten vegetables, but Hitchin knew that the crowd were likely to stone him. He wore a suit of armour under his clothes but the beating he received was so severe he had to be removed from the pillory before the hour had elapsed. He died of his injuries six months later.

With Hitchin gone, London was wide open for Jonathan Wild. In truth, London had been a city under Wild’s rule for quite a while before Hitchin’s fatal miscalculation. Wild’s reputation among legitimate society blossomed. Now he had no need to approach victims of theft or burglary. He conducted business out of an enquiry office and charged a consultation fee of 5s for anyone seeking his knowledge and advice. He organised his criminals well, partitioning London into a grid and apportioning each section to thieves whose skills and specialities were best suited to the area. To begin with, the underworld went along with Wild because his ideas were outstanding and he was a fair man to do business with, but ultimately they carried on doing business with him because they were afraid of him.

Since the beginning of his criminal career, Wild had made it his business to amass as much incriminating information as possible against anybody he came into contact with. He kept a ledger filled with his associates’ names. Against many names he would put either an X or XX. A single X meant that he had enough information to see that person hanged should the need arise. XX signified that he had made up his mind to have that person hanged. But information by itself wasn’t enough to secure Wild’s position. He also had the manpower to enforce his will and Wild’s intimate inner circle consisted of two extremely tough and violent men, Abraham Mendez and Quilt Arnold. They were his chief enforcers. Both men were fiercely loyal to their master and Wild seemed to have an uncharacteristic amount of faith in them, entrusting them with the administering of much of his empire. Wild also had a penchant for recruiting men who had absconded from the prison colonies overseas and had returned to England before their sentence had elapsed. This was a crime punishable by death and Wild used this knowledge as leverage to ensure the obedience of many of those under his command. Another recruitment technique was to catch potential criminals young. Wild inducted many of London’s orphans and urchins into his street army.

Jonathan Wild used his public persona as Thief Taker General to discipline and eradicate any unruly elements within the ranks of the underworld. It wasn’t enough that a Thief Taker contented himself with reuniting the burgled with their missing items, he also had to be seen to bring criminals to justice. Wild needed scalps, and any independent that refused to work with him was fair game. When an offer to do business with Wild was rejected, the thief would receive this warning: ‘I have given you my word that you should come and go in safety, and so you shall; but take care of yourself for if you see me again, you see an enemy.’ Wild excelled at exterminating the opposition, and when no obvious target presented itself, Wild would simply sacrifice one of his own to the gallows for appearances’ sake. But Wild could also use his power to keep the loyal out of trouble if their freedom and continued service was expedient to him. So, if one of his gang were arrested and put on trial, Wild had enough professional perjurers in his employ to ensure that the felon walked free.

The year 1718 saw another challenge to Jonathan Wild’s supremacy. This time the law made a belated move against him.

Not everyone in legitimate society was convinced by Wild. Admittedly, there were many who either knew or suspected that he was not all he claimed to be. In the main, these people were generally happy to let Wild exist, principally because the robbed were getting their stolen belongings back and many dangerous criminals were being tried, found guilty and executed. Ironically, on many levels, Wild was actually making the streets safe for respectable people. But there was a small contingent headed up by the solicitor-general Sir William Thompson that saw through Wild and regarded his existence and practice as an insult to the law abiding. Thompson sought to pass a law that at worst curtailed the greater part of Wild’s operations, and if all went well might even see him hanged. The Act made punishable by death the practice of receiving a reward for the return of stolen property. The Act was to become known informally as The Jonathan Wild Act. Wild’s response was to adapt, prosper and carry on as if the law had never been drafted.

From 1718 onwards, Wild’s methods were similar to those he had used prior to the Act but with a few crucial modifications that placed a greater distance between himself, the stolen objects and any money that might change hands. The most important thing Wild did was to drop his 5s consultation fee. The victim would still meet with Wild, who would make great play of quizzing the victim for information and updating them on the progress of his investigation. Eventually, he would give the victim a price to pay his shadowy colleague for the recovery of his things, as well as a location where the transaction could take place. Sometimes, on leaving Wild’s office, the victim would even be accosted by a stranger who would press a piece of paper into his hand, and written on it was the amount he ought to pay to get his goods back. If all went well the meeting would take place, the money would be paid and the goods would be returned. Wild would be thanked profusely and when the victim offered him money, he would refuse, stating that his only concern was his civic duty to the victims of crime. Whereas before 1718 Wild may have capitulated after a brief show of modesty and accepted a gratuity, he was now scrupulous in not being seen to take any kind of reward whatsoever. Behind closed doors the money was brought to Wild and he took the increasingly greater cut.

The new system worked well and Wild entered the most powerful and wealthy stage of his criminal career. He was now an incredibly rich man. He lived in a house in Little Old Bailey and would move to a larger one in Big Old Bailey. Like Hitchin before him he loved to be seen in public, sporting an expensive wig and coat with silver buttons, carrying a sword and a silver staff with a crown on top. He worked his way through a succession of attractive women who lived with him as his wife (ignoring the fact that he had never divorced his first spouse back in Wolverhampton). He lived extravagantly and in time developed a nasty case of gout. His empire expanded: he opened up other enquiry offices, he owned warehouses full of stolen items and ran elaborate blackmail scams. He bought a sloop. He established connections in Holland and organised the sale of stolen goods overseas. In spite of The Jonathan Wild Act, the Thief Taker’s standing among much of government was untarnished. Wild was even consulted by the Privy Council in 1720 about how to deal with the growing problem of highway robbery. Wild’s advice was to raise the reward from £40 to £100, a move that was entirely to Wild’s financial benefit as he made a point of persecuting highwaymen with an almost evangelical gusto, the highwayman being the most independent and the least servile of all Georgian criminals.

Jonathan Wild’s house, bought with the proceeds of his extensive criminal activities.

Wild’s position seemed unassailable and he reigned unopposed until the mid-1720s. Wild’s downfall came eventually and when it did, it wasn’t the law but an ill-disciplined, treacherous rag-tag bunch of thieves that laid the foundations. The leader of the gang was a young burglar and part-time highway robber named Jack Sheppard.

SHEPPARD

Jack Sheppard was the complete inverse of Jonathan Wild. He was flamboyant, reckless, intemperate and completely lacking in most of Wild’s more methodical qualities. He revelled in being a criminal and had little interest in preserving the veneer of social respectability so crucial to Wild’s survival. Unlike Wild, Sheppard had a talent for getting caught, an unfortunate quality that was offset by a genius for escapology.

Sheppard was a native of London, born in White’s Row, Spitalfields, in 1702. His father was a carpenter who died when Sheppard was small. Sheppard spent some time in the Bishopsgate workhouse, received a little schooling and was taken in and taught to read and write by a Mr Kneebone (a man whose kindness Sheppard would subsequently repay by robbing him). He followed his father’s trade and was apprenticed to Mr Owen Wood, a Drury Lane carpenter.

Sheppard liked to drink and he liked women. To his master’s consternation he spent his Sundays in the Sun Ale House in Islington. It was here that Sheppard met Joseph Hind who would introduce him to Elizabeth Lyon at the Black Lion Ale House in Drury Lane. Lyon was a thief, also known as Edgeworth Bess who, according to Sheppard, inducted him ‘into a train of vices as before I was altogether a stranger to’. He hadn’t known her very long before she was arrested for theft and placed in the St Giles Roundhouse. Sheppard wasted no time getting her out. He found Lyon’s keeper, threatened him with violence, took the keys, waltzed into the gaol and walked his mistress out.

White’s Row: Jack Sheppard’s birthplace. (Mark Nightingale)

Sheppard committed his first theft while working for Owen Wood, stealing some silver spoons from a public house in Charing Cross. His next crime of any note was also committed under his master’s nose. Sheppard had been employed to either make or fit some shutters for a Mr Baines. In July 1723 he stole 24yds of cloth from Baines. Failure to sell the cloth prompted Sheppard to hide the stolen goods in a trunk at his master’s house. He then had another crack at Baines’ house, entering through the cellar (having loosened the wooden bars while he was working). He stole £14 worth of goods and £7 in cash. Baines’ lodger was blamed for the theft but a fellow apprentice informed on Sheppard regarding the cloth he had hidden at Mr Wood’s house. It was a precarious situation for a while. Sheppard was obliged to break into Wood’s house and remove the cloth. Wood was keen to expose his apprentice as a thief and pressured Mr Baines to press charges. Sheppard tried to intimidate Baines into keeping his mouth shut, whilst Sheppard’s mother waded in on Jack’s side swearing that she had in fact bought the cloth for her son. Eventually, Sheppard was obliged to return most of the cloth but had managed to keep out of gaol.

It didn’t take long before Sheppard decided he had had enough of trying to juggle the tedious demands of legitimate employment with criminal activity. With a year left to serve, he abandoned his apprenticeship, moved in with Edgeworth Bess and became a full-time thief. Sheppard gathered round himself a loose collection of criminal affiliates and friends who would work with him on and off. Chief among them was Joseph Blake, who was known by the strange nickname ‘Blueskin’ (most probably on account of his dark complexion). Blueskin Blake was a prodigious sexual athlete, a vicious man, something of a coward and by all accounts a fairly incompetent thief with a talent (that he would share with Sheppard) for getting arrested. Prior to falling in with Sheppard, Blake had run with a violent gang that had imploded in an orgy of informing and counter-informing when a series of shootings and the murder of a Chelsea pensioner had brought the full weight of the law against them. Much of the gang was hanged. Blake had co-operated with Jonathan Wild and informed on many of his associates. The Thief Taker’s influence spared Blake the gallows and a sentence of transportation, but Wild couldn’t keep Blake completely out of trouble and he served time in the Old Street Compter. When Blake got out he began running with Jack Sheppard.

Modern Drury Lane. Sheppard first met Edgeworth Bess in a public house on Drury Lane. (Mark Nightingale)

Sheppard was arrested for the first time at a pub in Seven Dials. He had recently robbed another pub with his brother Tom. Jack and Tom had neglected to obtain permission from Jonathan Wild to carry out the robbery and consequently hadn’t paid their tithe to him. Tom was arrested. He informed on his brother to the Thief Taker. Sheppard was waiting in the pub for a man who was going to play skittles with him for money; he had been told by an associate that the man was an easy mark and ripe for a fleecing. The man turned out to be the constable of St Giles’ Parish. The person who had brokered the meeting was James ‘Hell and Fury’ Sykes, an agile and tough enforcer of Wild’s. Sheppard was locked up on the second floor of St Giles Roundhouse for the night. A justice would question him in the morning. As far as Wild was concerned, another upstart had been made an example of and the status quo had been re-established.

It took Sheppard three hours to escape from St Giles.

Sheppard had been admitted to the Roundhouse at around six in the evening. He had on his person an old razor, which he used to cut a hole in the roof. He placed his bed under the hole in order to catch any of the noisy debris that fell to the ground. By nine o’clock he had made a hole just about big enough to squeeze through. In an effort to force himself on to the roof, he dislodged a tile or a brick. The loose object slid over the edge of the roof and fell into the street, hitting a passer-by on the head. Sheppard had inadvertently attracted an audience. He forced himself on to the rooftop and dropped down into the churchyard. He scaled another wall and lost himself in the crowd. It was a reasonably spectacular breakout, but better was to follow.

Sheppard enjoyed a short spell of freedom before being arrested again. This time he was caught pickpocketing. He was locked in New Prison, Clerkenwell, being put in the condemned hold and chained up. Edgeworth Bess had also been arrested. Sheppard and Bess were put in the same cell as the authorities were under the misapprehension that the couple were man and wife. Both prisoners were allowed visitors and someone (in all probability Blake) managed to smuggle a tool in. This was all Sheppard needed to remove his fetters. Sheppard then began to work one of the bars on the cell window loose, and he and Bess climbed the 20ft or so down into the yard using an improvised rope made from prison bedding.

The site of New Prison, Clerkenwell. (Mark Nightingale)

Jack Sheppard escapes from New Prison, Clerkenwell, with Edgeworth Bess on his back. (Illustrated by Stephen Dennis)

The next obstacle in their way was a 25ft wall. Bess clambered onto Sheppard’s back and the thief climbed the wall without the aid of a rope or ladder, the locks and bolts acting as hand and foot holds. The two of them thereby climbed over the wall and made it safely to the street below and liberty. They parted company. Sheppard enjoyed a three-month hiatus from capture before he was taken for a third time.

Sheppard and Blake decided to rob Sheppard’s old benefactor, Mr Kneebone. They stole £50 worth of cloth but had trouble trying to fence their haul. Their choice of fence was William Field, a pathologically treacherous man who, unbeknown to them, was one of Wild’s informers. Field stole their cloth, went to Wild and began to tell tales.

Jack Sheppard was not a difficult man to catch. The notion of a low profile was a concept more than slightly alien to him. He was addicted to the same locales and drinking spots, and was cavalier in his defiance of Wild. He was also an appalling judge of criminal character with a deeply unreliable circle of friends. In July 1724 he was taken for the second time by Jonathan Wild. The Thief Taker met up with Edgeworth Bess and got her drunk. She gave away her lover’s whereabouts without too much persuasion and Wild sent Quilt Arnold to bring Sheppard in. Sheppard was incarcerated for the first time in Newgate Gaol.

Newgate had been a hated fixture of London topography since the Middle Ages. The gaol had assumed many different forms in its lifetime. It had crumbled and had been rebuilt. It had burned down in the Great Fire and had been rebuilt again. It had survived all of nature’s assaults to stand symbolic of the worst that the establishment could mete out on those that chose to flaunt its laws. It was a desperately overcrowded place that incubated disease. It was fortress-like, labyrinthine in design and believed to be impossible to escape from.

Sheppard was put on trial at the Old Bailey. Both Wild and Kneebone stood witness against him. Sheppard was found guilty, sentenced to death and placed in the condemned cell. Surprisingly, Sheppard was allowed visitors. This wasn’t deemed to be too much of a problem as the cell door was thick and sturdy. There was an opening at the top of the door but it was lined with metal spikes. Visitors were allowed as far as the door but not inside the cell. As Sheppard’s friends came to wish him farewell, one of them managed to smuggle a tool to Sheppard past the spikes. Sheppard began to work one of the spikes loose.

On 30 August the warrant for Sheppard’s death was issued. On the same day he was visited by two women. The guards were either drinking or else were distracted by one of the two visitors, and Sheppard managed to remove a spike, climb through the opening and literally walk out of Newgate. He and his two accomplices caught a Hackney Cab and disappeared into London.

Sheppard lasted ten or so days before being rearrested on Finchley Common. He had even left London at the behest of his friends and stayed in Northampton for a short while, but came back when the family he was staying with failed to treat him with the adulation he felt he deserved. Sheppard was taken back to Newgate and placed in the ‘Castle’, the most secure part of the prison. This time there were no visitors and Sheppard was handcuffed and chained to the ground.

A condemned cell in Newgate Gaol. Both Sheppard and Wild were held in cells like these before their respective executions at Tyburn.

Jonathan Wild must have felt that the tiresome and distracting war with this resourceful company of independents was finally coming to an end. Joseph ‘Blueskin’ Blake had also been captured. Wild, along with Abraham Mendez and Quilt Arnold, had personally arrested him. Blake had shown a degree of defiance in capture, threatening to kill Quilt Arnold with a penknife, but submitted to Quilt when he threatened to cut Blake’s arm off. Blake was locked up in Newgate and put on trial. Wild, Field, Mendez and Arnold all gave testimony against him and he was found guilty and sentenced to death. At Blake’s request, Wild came to see him at Newgate, and the two men met in the yard. Blake pleaded with Wild to use his influence to get his sentence commuted from death to transportation. Wild refused. Blake had a small penknife hidden on his person. He grabbed Wild’s neck and cut his throat. The point of the blade entered the skin just below Wild’s ear and Blake dragged the knife across the windpipe. Wild was wearing a muslin stock around his neck so the blade was hampered and missed cutting any arteries or the windpipe. Blake was quickly restrained and Jonathan Wild, soaked in his own blood, was rushed to the surgeons. Newgate was in shock. Prisoners were dizzy at the prospect that Jonathan Wild might actually be dead and Newgate’s gaolers had their hands full restoring order. As a consequence, Sheppard was not properly watched.

No one really knows how he did it, but Sheppard removed his handcuffs and somehow managed to break the chain between his legs and loose himself from the anchor that secured him to the floor. The irons around his ankles were pulled up and tied off to stop them impeding his movement. There was a chimney in his cell that offered a possible route out of the prison. Sheppard fitted himself inside the chimney and began to climb upwards. An iron bar blocked his way. He used bits of the chain he had broken to dig the iron bar out of the chimney wall. He carried on climbing a little further upwards and then used the bar to smash a hole through the chimney wall into an adjacent room. The room was called The Red Room. It was situated directly above the Castle and was completely empty.

Sheppard had broken into a deserted part of Newgate that hadn’t been in use for over half a decade. The Red Room was locked from the outside. Sheppard broke the lock, only to find a succession of locked doors and empty rooms between him and freedom. He alternated between brute force and delicate craftsmanship as he employed the iron bar and a nail he had found to spring locks or smash holes through walls to get at bolts. He passed through a chapel and broke off an iron spike adding it to his impromptu tool kit. The noise Sheppard was making was cacophonous, but the cells and corridors Sheppard passed through were empty and the din didn’t seem to attract any unwanted attention. Mercifully, the last door was bolted from the inside. Sheppard drew the bolt and stepped into the fresh air. He could see London below him.

Joseph ‘Blueskin’ Blake cuts Jonathan Wild’s throat at Newgate Gaol. (Illustrated by Stephen Dennis)