Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Between clubs, dining halls, libraries, institutions and good addresses in the country, R.B. McDowell, born in September 1913, had led the charmed and energized existence of a distinguished bachelor don, embellishing the lives of generations of students – chiefly Trinity College undergraduates – fellow historians, academic colleagues and friends. In McDowell on McDowell, A Memoir, he describes this life, almost entirely shaped by a seventy-five year association with Trinity College, Dublin, with interludes at Radley, Oxfordshire during the second world war, in London after official retirement in 1981 and on the Continent for vacations. With spare, poised prose, which reveals as it conceals, he tells of origins in Edwardian Belfast and evokes memories of secondary education at Elmwood Sunday School, annual visits to London, and summers at Fahan and Portadown. He survives the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918, and experiences widening social and intellectual contours informed by avid reading in military history, eighteenth-century British politics, nineteenth-century fiction, Adam Smith, Marx and Spengler. In 1932 he progresses to TCD as lecturer, historian and writer, coming to identify with eighteenth-century Ireland – its buildings, politics and people – as the primary focus of his interest and work in a moving expression of its ethos and his own. He also provides fascinating, vivid cameos of Europe in crisis: visiting Cologne in January 1939, and in May 1968 joining student radicals on the Boulevard St Germain in Paris, an experience turned to account as he dealt with home-grown Internationalists in his capacity as Junior Dean (1956-69). This entertaining essay is self-portraiture, conveyed with the perception and ease of an after-dinner speaker and raconteur, alive to the idiosyncrasies and vagaries of his profession, is a valuable record of a unique Irishman and citizen of the world at the close of his days. R.B. MCDOWELL, who has been the subject of two volumes of tributes and reminiscences edited by Anne Leonard (The Junior Dean: Encounters with a Legend, 2003, and The Magnificent McDowell: Trinity in the Golden Era, 2006), is Emeritus Fellow and former Professor of History at Trinity College, Dublin. His own writings, from Irish Public Opinion 1750-1980 (1944) to Ireland in the Age of Imperialism and Revolution 1790-1801 (1979), include editions of Edmund Burke's letters and Theobald Wolfe Tone's journals, and biographies of Alice Stopford-Green (1967) and (with W.B. Stanford) J.P. Mahaffy (1971). The Lilliput Press has published four of his previous works: Land and Learning: Two Irish Clubs (1993), Crisis and Decline: The Fate of Southern Unionists (1997), Grattan: A Life (2001) and Historical Essays, 1838-2001 (2003).

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 254

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2008

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Illustrations//

Preface//

I. Boyhood//

II. Undergraduate//

III. Postgraduate//

IV. Post-War Trinity//

V. Junior Dean//

VI. Advancing Towards Retirement//

VII. London//

Epilogue//

Copyright

Illustrations

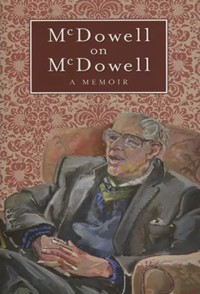

Frontispiece: R.B. McDowell, Sophie McCormick (2006, oil on canvas)

Staircase// 44

Kitchen// 80

Dining Hall// 114

Botany Bay// 130

Rubrics// 154

Back Gate// 180

Preface

SOME TIME AGO I began to make autobiographical jottings. These have now cohered into a memoir. Contemplating the final result I naturally wonder if it is worthwhile publishing it. Without indulging in false modesty, I must accept that I have not been very distinguished; nor have I played a significant role in great events. However, I have been for many decades connected with a well-known academic institution; for nearly seventy years I have been engaged in the study and writing of history, occupations on the whole respected in the contemporary world. I have resided happily in three very distinctive cities, and have lived through two world wars and a pandemic. I feel I may be able to supply a few historians with some small items of useful information and so may very occasionally figure in a footnote.

Rather to my surprise I have discovered that writing an autobiography is more difficult than producing an historical monograph, especially when the material is limited, as in this instance. I have never kept a diary; little of my correspondence survives; official sources are bleak. Therefore to a very large extent I have had to rely on my memory, and I have had to take good care that memory is not dangerously supplemented by invention. I am very conscious that the personal pronoun singular is strikingly conspicuous in my text. But autobiography demands it. To me, I am a ‘special subject’, on which I am exceptionally well informed, if decidedly biased. I may indeed be criticized for dwelling too intensely on myself, reducing the other people I mention to the role of a supporting chorus. But I am afraid if I attempted to portray my friends and acquiantances more fully I would fail to do them justice and would probably use knowledge acquired implicitly in confidence.

Nevertheless I must emphasize that friends have greatly contributed to my enjoyment of life and in some instances have markedly influenced my intellectual development and lifestyle. I am also conscious that being reminded of my limitations and faults may dismay some of those who read this memoir, especially if they have endeavoured to view me in a kindly light. But I have endeavoured to be candid, even though candour is combined with a strong degree of discretion.

Finally, I must acknowledge with gratitude the assistance, often unintentional and unconscious, given to me by a number of people in the preparation of this work. I wish to thank emphatically Dr David Dickson for advice and technical help. I am also indebted to the staff of The Lilliput Press, especially Fiona Dunne, for their invaluable help.

December 2007

I

Boyhood

I WAS BORN in south Belfast on 14 September 1913 a few years too late to be an Edwardian, but indubitably pre-war. My parents both belonged to large families, my father being the eldest of fourteen children and my mother the youngest of nine, therefore I had numerous uncles and aunts scattered over the globe from Australia to Berlin. These included the head of a well-known engineering firm, the founders of a small and successful engineering business, a doctor, a colonial civil servant, hospital nurses and, by marriage, a bankman, a very senior Australian civil servant, a German stockbroker and a doctor prominent in civic life. My paternal grandfather was a Presbyterian farmer in King’s County, upright but not very successful. About 1895 he was offered the commission of the peace but, disapproving of the ‘Morley magistrates’, he declined it. My father left home early and entered a solidly established Belfast tea firm of which he ultimately became a director.

My maternal grandfather was a Londonderry wine merchant with a retail outlet, a pub, never mentioned in the family. From the fragments that drifted to my parents’ house he had a good collection of books, especially of Victorian travel. It was long remembered that at Londonderry City dinners when trifle was served, an elderly waiter used to say, ‘Cut deep, Mr Ferrris, cut deep,’ and so get down to the sherry. He was adored by his daughters whom he used to take on a thrilling walk through the tunnels on the Londonderry–Castlerock railway line, teaching them that if they heard a train to search quickly for a manhole in the tunnel wall. Robust girls, they enjoyed the experience. His wife, Henrietta Laurence, was from Liverpool. Very correct with a sense of style, she was the niece of an Anglican clergyman who, it was said, possessed a very large library, which he successfully defended against female borrowers. If a lady asked him for the loan of a book he would immediately say, ‘Please take it as a present.’ It was a good deterrent.

About 1910, my mother, living in Londonderry, and my father in Belfast, first met. My mother was travelling by train to visit friends in the North and, a sheltered young woman, she was dismayed to discover she had lost her ticket and had very little money – at home everything could be bought on account. However, a nice gentleman in the carriage dealt with the ticket collector, lent her money and, before the end of the journey, made up his mind he was going to marry her. He, of course, had to overcome a serious obstacle – they had not been introduced. But after diligent enquiries he found that a friend knew my mother’s parents and could take him to her home.

My parents married in 1911 and, after a honeymoon in London, at the newly opened Aldwych Hotel, returned to settle in Belfast. They were distinctive personalities, in many ways strikingly different. My father, not tall but sturdy and always perfectly turned out, was energetic, good-natured, impulsive and easygoing. My mother, with masses of black hair and fine features, was delicate and frail-looking. In her youth she was a vigorous tennis player and dancer, and until very elderly a competent motorist. In social matters she was a formalist: an intelligent conformist to the Edwardian social code. At times she faced the problems of life with apprehension – it was an age when middle-class women suffered from nerves. If my father believed in ‘dropping in’, she emphasized the restraints that manners imposed on spontaneity. These differences in temperament were frequently illustrated when they had to deal with financial matters. My father adopted a cavalierish attitude to bills; my mother eyed the totals with dismay.

What I, a censorious teenager, mentally and sometimes verbally adjudicating on the conflict, overlooked, was that my father was a very shrewd businessman and my mother a generous woman far from parsimonious. In fact, they both greatly enjoyed the pleasures of life, were very ready to help those in trouble and intently appreciated one another’s company. Oddly enough my mother, though well equipped with household skills, didn’t cook. My father did. Starting with sauces, he finally purchased a Mrs Beaton. Of course, until 1939 he rarely managed to get into the kitchen, although his knowledge made him an informed critic of food and wine, a quality he shared with my mother; they both greatly enjoyed a good restaurant meal together. In fact, it was only in my twenties that it dawned on me that it was a most happy and successful marriage.

My mother’s emphasis on formality, derived from, I think, her mother, greatly influenced and benefited me. Though not an intellectual woman she based her teaching of manners on two general principles, consideration for others and common sense; the result was that when I went out into the world I believed I knew the right way to behave as well as the rules of dress and general deportment. I am afraid I must add that I observed with concealed contempt the failings of others in those areas. I may have been unpleasantly critical but at least I was self-assured and at ease socially. I also discovered about the age of sixteen a literary guide to good behaviour, LordChesterfield’s Letters (Everyman edition). It may seem strange that a raw, unsophisticated Belfast schoolboy should receive instruction from an accomplished eighteenth-century nobleman on the value of graceful manners and how to become socially acceptable, but to some extent I resembled the clumsy youth to whom the letters were addressed. I now sometimes look with gratitude at the simple, elegant monument that Lord Chesterfield erected in Dublin. Another work that greatly helped to form my conceptions of good behaviour was Thackeray’s Book of Snobs, which I read and reread (there was a copy in the house). In it Thackeray, a hugely perceptive and sardonic Victorian gentleman, in a series of vignettes describes and satirizes many instances of social pretensions, upward-mobility striving and tuft-hunting – warning me in advance of the sins I was inclined to.

After settling in Belfast my parents occupied three houses in rapid succession – a villa in Bawnmore Road, near Balmoral, was followed by a terrace house in Ulsterville Avenue (a dreary thoroughfare terminating in a railway embankment, which offered my mother an excellent view from her bedroom window of the city cemetery on a distant hill). Early in 1918 we moved to No. 88 University Street, the family home until 1957. One of the earliest events in my life, which naturally I don’t remember, was when my mother, out at the theatre, began to worry and hurried home. She found that a newly engaged nurse (the term ‘nanny’ was not yet in vogue) was about to plunge me into a bath of water so hot that it took the skin off my mother’s fingers. When being remonstrated with, the nurse explained that if the water was too cold the baby turned blue and if it was too hot, red. In fact, I was about to be treated as a human thermometer. Earliest memories, from about the age of three, circle round two striking figures – Sergeant Trumbly and Alice. When I was walking with my nurse and perambulator along the Lisburn Road we sometimes met the sergeant, very tall, in RIC uniform, and his salute gave me a great glow of gratification. Alice, our maid, was English, elderly and a devout Catholic. In a well-starched white apron, she was punctilious and kind.

Shortly after Alice came to the house, my mother was struggling at the piano with a new piece of music; Alice asked to be allowed to try it and my mother realized at once that Alice was a far better pianist than herself and encouraged her to use the piano. Alice’s story was a strange one. As a young, well-educated girl, she had run away from home and from then onwards remained in domestic service. When there were two young children in Bawnmore Road she found it a strain and went to a quieter household. Soon afterwards she retired and her employers, including my father, arranged that she should enter the Shields Institute, Carrickfergus, which was a number of small, one-person houses. The inmates were able to live independently but for emergencies there was a matron in the background. Alice with her memories, links with past employers and her religion, was a very cheering person to visit.

Other early memories are connected with a vague phenomenon – ‘The War’. I cried bitterly when my maternal grandmother gave her sugar ration to my baby brother, Patrick; ‘Fair play is for all’ was my slogan. I had a vehement admiration for soldiers, and when just able to walk I staggered around a military hospital distributing magazines. One Christmas, Santa Claus in a big shop gave me a cardboard toy displaying the Kaiser flanked by Hindenburg and Ludendorff, together with a pea-shooter. Also I heard, wondering what it meant, that the owner of the hairdressing establishment I patronized, Mr Hoffman, had ‘been interned’. With the war vaguely in the background, early in 1918 we moved to No. 88 University Street, a dwelling that made a deep impression on me. It was a three-storied, bow-windowed Victorian terrace house with about nine rooms and the usual ‘offices’. To a schoolboy like me it was very spacious, but when I visited it in about 1980, after years of living in institutional grandeur, the rooms seemed comparatively small. No. 88 was then the headquarters of the Alliance Party, my old bedroom being the leader’s study.

The house provided adequate accommodation for my family, my parents and my brother along with myself, a cook-general and my brother’s nurse, who was to be replaced in time by a mother’s help. The milkman, the breadman and the laundryman called frequently; the coalman less often. A string of messenger boys brought parcels, the contents of which were distributed between three pantries. The cook-general spent a substantial amount of time in the kitchen and my mother helped her with the housework, regulated by weekly routine with a great upheaval in the spring. My mother also paid sustained attention to her children, went shopping and met her friends – ‘calling’ and being ‘called on’. The day culminated for her and my father at dinner, which was a three-or four-course meal. In Belfast, in some ways a very divided city, a marked division was between meal patterns. Some people had breakfast, dinner (about midday) and high tea (a mixture of cake, bread and butter and meat); others had breakfast, lunch, afternoon tea (about 4 pm) and dinner at about 7 pm. My parents adhered to the second pattern. When starting to go into the world, I quickly learned when asked to tea to find out at what time was I expected. A school contemporary once told me in strict confidence that his family (as we would now say, upwardly mobile) had decided to change from high tea to dinner. I was thrilled at being a confidant.

No. 88 was kept warm by the kitchen range and, if necessary, by a coal fire in at least one room. In addition there were some gas fires, each with a bowl of water in front of it. In the 1930s electric fires replaced the gas ones. The ‘wireless’ arrived about 1924. ‘Listening in’ could be trying. We sat round the set, each with his or her own earphones. There was always the danger that an impetuous listener (my father for instance) might move quickly, forgetting his earphones and bringing the whole contraption crashing to the floor. The gramophone, which arrived about the same time, also needed careful handling. If the turntable was not stopped in time the record was scratched. With the gramophone I associate the annual popular song – one year it was ‘Yes we have no bananas, we have no bananas today’, the next year it was ‘Felix keeps on walking, he keeps on walking still’. But these frivolities were submerged by the ringing notes of Clara Butt singing ‘Land of Hope and Glory’.

In contrast we had a record from the south of Ireland, ‘The boys who beat the Black and Tans were the boys from County Cork’, which my brother, myself and our friends would sing ironically. We also had a fair amount of drawing-room music. My mother was a keen pianist who played by ear, and when my brother became a violist she greatly enjoyed accompanying him. My maternal grandmother, a frequent visitor, was also a keen pianist, playing strictly by sight. This sometimes put her in an awkward position at Londonderry haute bourgeoisie parties. At such gatherings it was usual for some of the guests to be asked to make musical contributions, and of course it was good manners for them to express surprise at being requested to do so. But my grandparents could not be coy; she arrived armed with her music and his instrument was the double bass.

Shortly after we moved to No. 88 an event occurred that had a deep long-term effect on my life. One morning shortly after I had started at a kindergarten I felt strangely uncomfortable, I would now say feverish. I remember distinctly lying in a large chair with my parents and our doctor looking at me solicitously; then I lapsed into unconsciousness, which lasted for approximately three weeks. Later I gathered that I had been attacked by the prevalent flu that had developed in my case into double pneumonia; I had been so ill that at one stage the doctor (an outstanding GP) felt he must tell my parents that I probably would not survive the night. My parents were both down with the flu themselves, my brother was ill and his nurse died. The maid was the only member of the household on her feet and she coped splendidly. Since good nursing was at that time the best and perhaps indeed the only effective remedy against flu and its developments, it was very fortunate that our doctor secured two hospital nurses – one an army nurse convalescing – who in the emergency had come back to work.

With devoted and skilled attention I pulled through, and one day was carried by the nurse to the window to see a large Union Jack flying from the house opposite: ‘We have won the war’, I was told. It was the eleventh of November 1918. The great flu epidemic was a frightening appendix to the war and in my youth many grim stories were told about it. To take one example, in 1918 a young man came into Trinity College Dublin to call on his future tutor. When they were chatting they saw an undergraduate collapsed on the Examination Hall steps and they carried him to a ground-floor set in Botany Bay, where rows of helpless undergraduates were lying on the floor waiting for ambulances to take them to hospital.

My major flu-pneumonia attack left me vulnerable for years to severe colds, mild flu attacks and bronchial trouble, so my parents thought I must live a comparatively sheltered life, though very sensibly they didn’t stress my disabilities. Until I was about eleven I was educated at home by a governess. When she resigned on getting married, I was sent to a day public school, ‘Inst’ (The Royal Belfast Academical Institution), within walking distance of No. 88, and even so I was often absent from school for long stretches. My mother and the doctor were wise to be careful because I was understandably a frail boy, though now I suspect that naturally I tended to overstress my weaknesses. School was quite bearable, but nevertheless I greatly appreciated the comforts and freedom of home (even if confined to bed or one room).

When I became more involved in school social life, my health steadily improved. As might be expected, I did not play games, my stamina was poor, my eyesight bad and I was easily able to abstain because ‘Inst’, very distinguished in games, distained having conscripts on its teams. The only pressure I came under was from a good-natured master who, keen on athletics, asserted the value of games. I defended my freedom of choice – all this being a pleasant relief from classroom routine. Once he undoubtedly scored a point when he asked me what I proposed to do instead of playing cricket. I replied, ‘Read Macaulay, Sir.’ ‘Macaulay,’ he retorted, ‘pure journalism, read Gibbon, boy.’ I did so with delight. In such a tolerant atmosphere I never saw myself as an aesthete confronting the hearties; I knew many keen games players, sometimes even drifting along to watch their activities.

For about ten years after my great illness, compared to my contemporaries I lived a rather solitary though not isolated life – home-centred, self-entertained and, to some extent, self-taught. Amongst my games were building card houses (using three packs), my large collection of tin soldiers and ‘the parliamentary game’. From about 1920, I was building up three armies: a British, a colonial (including Sikhs and a small and expensive camel corps) and a foreign army (French and Italian). I had four armoured cars of the cage version made at the request of a family friend in an army or auxiliaries workshop, a tin soldier being lent to provide scale. I enjoyed my visits to see the mechanic at work and being saluted. I had also a large cardboard fort and created a varied terrain by laying a green cloth on piles of books. A fleet of paper boats, very easily constructed if one had been taught the knack, enabled me to stage amphibious operations. Most of my military engagements were based on imaginative interpretation of my reading of popular, lavishly illustrated war books.

There was also the parliamentary game, my own invention, which was inspired by reading Sydney Lee’s QueenVictoria, and Bingham’s The Prime Ministers. It had at its base a large sheet of paper on which were drawn two oblongs, the House of Lords and the House of Commons, together with a large number of small squares of cardboard, white on one side, brown on the other – they were MPs – and five-sided pieces, who were peers. At a general election the square pieces were tossed like dice, those coming up white counted as conservatives, those coming up brown as liberals. An MP who was created a peer had two corners of his counter cut off. The creation of peers, sessional proceedings and bills involved much paperwork. In the end the complexities of the game made it very exhausting to play – a warning perhaps against too much government. I must admit that I sometimes tampered with the result of a general election if it did not fit into my plans, anticipating the conduct of the European dictators who used democratic forms to cloak arbitrary rule.

Other pleasures were less solitary. There were children’s parties, with ices, games (musical chairs, hide-and-seek), and on one occasion a large screen in a drawing room on which a Charlie Chaplin film was shown. I sat too near the screen and was bitterly annoyed by everything being distorted. I learnt to dance at classes run by the celebrated Mrs Whale, a commanding figure (a retired actress), dressed magnificently in black silk. She taught us to polka, waltz and foxtrot – my grandmother taught me the lancers. Far too self-conscious to be a good dancer, I was one of Nature’s sitters-out. Nevertheless I did enjoy waltzing. About sixty years later, waltzing with a good-looking girl at a Boat Club dance, I remarked how much I enjoyed waltzing. ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘my grandmother told me you waltzed splendidly.’ This rather dashed my gallantry.

Occasionally on Sunday mornings my father took me for a walk along the deserted quays, with a fine view of the shipyards and their gantries, symbolizing Belfast’s economic strength. Or we might visit the fire station and watch firemen slide down steel poles from their dormitories to the engines. It was also arranged that I should have a trip on the footplate of a railway engine. I travelled from Victoria Street station to Lisburn, fascinated by the glowing furnace into which the fireman continually shovelled coal. An occasional treat was a visit to the dignified Victorian building in Anne Street, which housed my father’s firm. On the ground floor were offices, and beside them a stable. On the other floors were stacked masses of tea chests, waiting to be taken by horse and cart to a railway station. Late in the afternoon, looking down from a high window, you could see a mighty army of cloth-capped men marching along Anne Street from ‘The Yards’.

Sometimes I would witness a tea-tasting, a solemn ceremony with considerable economic implications. My father in a tailored linen coat (his vestment), surrounded by respectful acolytes, would take in turn each of a series of small cups from a tray, sip its contents slowly, then spit the tea into a spittoon – steadily dictating notes. With my mother I went shopping. It was exciting to visit the three great cornucopias that dominated central Belfast. Of these Robinson Clevers, with its marble staircase, seemed to me somewhat aloof. Anderson Macauleys seemed dull. But the Bank Buildings held my allegiance. There I saw endless vistas of clothes and carpets, with small cash-carrying machines reminiscent of Alpine railways buzzing overhead and shop-walkers in frock coats, with manners suggestive of a court, ushering customers to the counters.

Before I was available as an escort, my mother was involved in a mildly embarrassing contretemps in the Bank Buildings. Her beloved Irish terrier Barney slipped away and returned with a large muff which he laid quietly at her feet. For a moment it seemed that his mistress had devised a novel form of shoplifting. I also went with my mother to ‘tea in town’, a great treat, often meeting with friends in the Carlton, all bright and elegant. A feature of these parties was plates of small cakes, two pence each. A well-trained waitress would at the beginning of the meal count the cakes and so would know when making out the bill how many had been eaten, but a clumsy waitress would ask each guest, ‘How many cakes?’ I was often deeply embarrassed. I still remember vividly being at a thé-dansant in the Carlton about 1919 and sitting at the edge of a chair, well supplied with cakes, watching my mother dancing with a khaki-clad partner. I felt I was in the whirl of fashion.

As a family we steadily supported the theatre and the cinema. Belfast had three theatres – the Royal Opera House, the Hippodrome and the Empire. At the Royal I saw Shakespeare (with the Benson Company, with Benson at the age of seventy, a handsome Hamlet), the annual pantomine, which I struggled to reconcile with what I believed to be the authoritative version, and touring companies playing West End successes, including a number of drawing-room comedies. One show, Cavalcade, greatly impressed me. It was magnificent theatre and I was thrilled when the spotlight fell on the name Titanic, near the lovers happily sitting on deck. The Hippodrome staged variety shows, and the Empire, associated with low comedians, was regarded as unsuitable for ladies and the young.

Oddly enough at the end of my school career, I and some of my contemporaries started going to the Empire, encouraged by a master who wanted us to see old-fashioned acting in the Henry Irving tradition. Naturally as students of the drama we felt very superior to our fellow patrons of the Empire. I well remember The Speckled Band with a frightening snake and blood-curdling screams. I also remember my deep disappointment with another Empire production, A Royal Divorce (a play about Napoleon and Josephine), which was advertised by huge posters running the length of a long hoarding, showing the Grand Army advancing in serried ranks towards Moscow. But when I saw it on the Empire stage, the Grand Army consisted of some supers marching round and round at the back of the stage in shabby, ill-fitting uniforms. The cinema was a welcome novelty to my parents’ generation. The Belfast picture houses were rather pokey until the Classic was opened in the late 1920s. Magnificent, with a good and not very expensive restaurant, it was patronized for lunch by my mother, her friends and their children. My father, of course, stuck to Thompson’s and the Abercorn, heavy in décor and food. The stars that enthralled me are now legendary figures. I was devoted to Charlie Chaplin and thrilled by Harold Lloyd (I knew nothing about ‘stunts’). I was greatly impressed by the Gish sisters in Orphans of the Storm – watching with intense anxiety Danton carrying a reprieve for the hero, desperately riding to the guillotine. To my immense relief he arrived in time.

I now come to the recreation that was to be a fundamental element in my way of life – reading. It was to shape my thinking, sharpen my wits, form to a great extent my conception of reality and provide me with endless pleasure. I have become indeed so addicted to reading that if there is nothing else available I am capable of intensely studying an out-of-date timetable. My earliest reading was what might be expected – fairy stories, children’s editions of Gulliver’s Travels and Robinson Crusoe, The Tanglewood Tales, the Wonder books and the Belfast Newsletter. In No. 88 there were plenty of novels, travel books and Chamber’s Cyclopaedia. My father read sonorously to me Scott’s Lay of the Last Minstrel and Marmion, and I read his Tales of a Grandfather, a work by an expert on Scottish history and a master of narrative admirably suited to a youthful reader. Amongst the novels was that classic of the cloak-and-sword genre, The Three Musketeers. It made history vibrant, though at first glance left me somewhat puzzled. The hotels of the French noblesse were very different to the Northern counties in Portrush and I could not fathom what ‘a mistress’ was. I read a vast number of Dumas novels and was delighted in the 1970s to stay in his Chateau of Monte Cristo, sleeping under a marvellous Moorish ceiling.

In complete contrast to Dumas, I also found good examples of the literature of dissent in the house – Henry George’s Progress and Poverty, Winwood Reade’s The Martyrdom of Man, H.G. Wells’ Tono-Bungay, great fun with serious implications, and South Sea Bubbles, highly critical of missionary activities that of course I supported by contributions to church collections and by attendance at bazaars. These works, probably purchased by my medical uncle, did not markedly influence my outlook, but reading them taught me that attacks on orthodox thinking had to be met by intelligent arguments. Thinking about my early reading I feel very grateful for the guidance I received from my governess. A vigorous young woman with an abundance of common sense, she made the study of history and literature an enthralling adventure. My first history book was Little Arthur’s History of England, a readable account of successive reigns. Having learnt my kings and queens I went on memorize the kings of France, the emperors of Germany and the British prime ministers. The popes defeated me. Devotees of social history may scorn this emphasis on the dynastic and the personal, but the lists provided me with useful chronological frameworks.

From about the age of ten, the Linen Hall Library, a quarter of an hour’s walk from home, became a place of continuous pilgrimage. The Library was the Belfast equivalent of the London Library and half a century older. Occupying two floors, subdivided into several rooms and broken up by large blocks of shelves, it offered endless surprises and pleasures. For instance, I found bound volumes of the Strand and read for the first time the Sherlock Holmes stories as they originally appeared. I also had access to a set of The Illustrated London News and, starting with wars and revolutions, obtained an absorbing contemporary pictorial account of ninety years of history. The Library was well supplied with general literature and fiction, and as my family could borrow up to three books at a time I was continuously supplied. It was in the Linen Hall that I first met an antiquarian – a tall and shambling man with an ill-trimmed beard, who was an expert on Belfast topography. Occasionally I walked part of the way home with him and once he took me to his house to tea with his wife. This contact with erudition was very exciting. ‘Inst’ also had an excellent library, kept steadily up-to-date by a most helpful librarian. I sometimes secured the key to the large cases at the back of a classroom to which rejects from the library were exiled and browsed happily amongst the outdated and third-rate.

To the libraries must be added the bookshops, which from about 1923 I frequented as a purchaser and a reader – Mullans and Greers. In Mullans, the principal Belfast bookshop, I bought Everyman and Home University volumes, and a number of G.A. Henty novels. The Everyman series (two shillings each) was a reminder that major literary and intellectual