Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

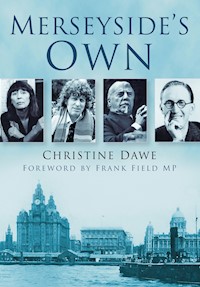

Merseyside has been the birthplace or home of literally hundreds of extraordinary men and women over the years. Modern-day noteworthy figures, such as Kim Cattrall, Daniel Craig, Beth Tweddle and Patricia Routledge rub shoulders with the historical great and good, including Sir Thomas Beecham, George Stevenson and Lady Emma Hamilton. Personalities from all eras and walks of life are featured, from politics, art and industry to music and entertainment. In this book Christine Dawe has penned a fascinating selection of mini-biographies of Merseyside's most famous sons and daughters to make a perfect souvenir for visitors to the area. This is also essential reading for Merseysiders everywhere, and is sure to appeal to those wanting to know more about these people's contributions to the Merseyside we know today.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 261

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To my dearly loved friends and family

The author in the ITV series How We Used To Live.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

Cyril Abraham

Jean Alexander

Arthur Askey CBE

Dame Beryl Bainbridge

Hugh Baird

Tom Baker

Sir Thomas Beecham

Dr Anne Biezanek

Lord Birkenhead (F.E. Smith)

Maud Carpenter OBE

Kim Cattrall

Edward Chambré Hardman & Margaret Chambré Hardman

Frank Cottrell Boyce

Sir Samuel Cunard

The 13th Earl of Derby & David Ross

Charlotte Dod

Brian Epstein

Lady Emma Hamilton

Dame Rose Heilbron

Shirley Hughes

J. Bruce Ismay

Alan Jackson

Amy Jackson

Sir Oliver Joseph Lodge

Colin James Paul McKeown

Florence Maybrick

Wilfred Owen

Sir Alastair Pilkington

William Henry Quilliam

Eleanor Florence Rathbone

Roly & Rust

David Stuart Sheppard

Fritz Spiegl

George Stephenson

Sir Henry Tate

Mirabel Topham

Robert Tressell

Beth Tweddle MBE

Frankie Vaughan OBE, CBE

Derek John Harford Worlock

David Yates

Copyright

Acknowledgements

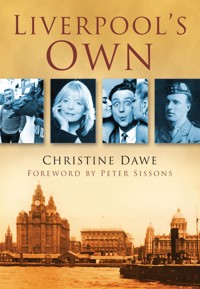

As with my previous book, Liverpool’s Own, I honour the memory of three brilliant people without whom no literary work of mine could ever have been possible. My debt to their talents and dedication is boundless. They are Mr Charles Babbage (1779–1869), Mr Peter Mark Roget (1791–1871) and Mr Oxford Concise!

My sincere thanks go to my editor at The History Press, Michelle Tilling, whose kind support, patience and understanding have been of the utmost importance to the successful conclusion of this and my previous book and recently also Richard Leatherdale. Eileen Brewer, as always, is the person to whom I turn for her IT skills, so superior to my own. Her invaluable help at any time of the day is matched only by her tolerance and unfailing good nature.

For technological support over and above the call of friendship, especially in respect of photography and electronic images, no-one could have been more helpful and constantly amiable than Dougie Redman, Runcorn’s gift to Merseyside.

For unfailing support in literary and content references plus suggestions for topics, I am forever grateful to John Goldsmith MD, FRCP; Nan McKean BA (Hons); Bill McKean RD, MB, ChB, FRCGP; Geoff Woodcock BA, MA, PhD, FRA; and Jenny Woodcock BA, PhD, FR (Scot). Also to John Frodsham, Assistant Principal at St Helens College, Tim Bolton and Francesca Garner at Hugh Baird College, Hannah Longworth at Pilkington’s World of Glass, Tony Hall at the Liverpool Echo, Sophie Callender – PA to Beth Tweddle, Fiona Whitfield at the Lancashire Wildlife Trust, William (Billy) Dean at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Sharon Ruddock at L.A. Productions, Professor Paul Baines – Head of School of English at Liverpool University, Nathan Pendlebury at the National Museums and Art Galleries Merseyside and all the receptionists and curators at the Chambré Hardman House, National Trust, 59 Rodney Street, Liverpool.

To all the present-day celebrities and their agents and P.A.S., I also send my sincere appreciation and good wishes for their continued success, as our wonderful ambassadors for Merseyside.

Foreword

By the Right Honourable Frank Field,

Member of Parliament for Birkenhead

Nobody who has read Liverpool’s Own will be surprised that Christine Dawe is back, as they say, by popular demand. If anything her selection of Merseysiders who have helped build the nation is even more surprising. I say surprising because I had little idea of just how many of the famous of our country have roots in Merseyside, or who have made their names here. Arthur Askey, Sir Thomas Beecham, Dame Rose Heilbron are just a few of the surprises this time.

I would like to concentrate on one person who was born and bred in Liverpool and who was for much of her life the most outstanding back bench member of the House of Commons since William Wilberforce – of anti-slavery campaign fame. I am talking here about Eleanor Rathbone, of course.

The name Rathbone is still well known in Liverpool, but I sometimes wonder whether today’s school generation hear much of her great work. It is therefore doubly good to have her presented in Merseryside’s Own. While, of course, she was in every sense Liverpool’s own, Eleanor was owned by a far, far larger audience. This body of world citizens stretched beyond our shores, beyond the darkest corner of Nazi Germany to the far reaches of what was then Imperial India.

Eleanor helped change the financial position of mothers. She fought the subjection of women to the caste system in India. Eleanor was also instrumental in trying to persuade the Allies to make saving the Jews one of the West’s war aims. It is to the Allies’ eternal shame that they did not do so but, undaunted, Eleanor immediately set about saving as many Jewish children as she could. One of the most moving events that I have ever attended at the House of Commons was a celebration to mark the fiftieth anniversary of her death. Elderly Jewish gentlemen rose to testify how Eleanor had saved them and, by saving each one of them, saved the world for them.

Eleanor was an independent MP – she belonged to no political party. Here perhaps is the reason she isn’t better remembered today; there is no political party claiming her as one of their great heroes. But possibly it is because she was a woman, and Britain has a terrible habit of seeing heroes in terms all too often of men. Both Liverpool’s Own and Merseyside’s Own show that women have been and are still prepared to make significant use of their talents and dedication to contribute to the welfare of our region and, indeed, to the whole nation. And that too tells us something special about Merseyside.

Introduction

Merseyside has everything anyone could possibly want. Within this region, there is such a wealth of variety, anyone could spend a lifetime inside its boundaries and still see something different every day – from fine, white, sandy beaches, sandhills and pine woods, to a thriving metropolis – from a sixteenth-century hall to a safari park – from potato plantations to numerous huge and elegant parks. Merseyside boasts three professional football clubs, Liverpool, Everton and Tranmere Rovers. There are rugby clubs, golf clubs by the score, riding schools and an international tennis tournament. For industries, take your pick between ship building, glass manufacture, real ale, pharmaceuticals, Jaguar cars and award-winning film and television productions. Miles of docks look out across the sea to Ireland and America and Merseyside’s art galleries, theatres and classical concert halls are unrivalled for quality and popularity. As for pop music – need I say more?

Three universities and numerous colleges offer the widest possible choice of subjects. Ask any local student where the best nightclubs and bars are to be found and they will say, ‘Look around you.’

Where else would you find two of the finest examples of under-river road tunnels? Passengers on the most luxurious cruise liners in the world admire the superb architecture of the Merseyside waterfront and, ‘if you want a cathedral, we’ve got one to spare!’ Of course, none of this came into being overnight. It has taken our ancestors centuries of effort and ingenuity to establish what we now take for granted. But none of the man-made venues could have been created without the existence of the River Mersey itself. This river has flowed out from its wide estuary into the Irish Sea since time immemorial. It has always been the lifeblood of the region. Before man settled in the surrounding countryside, the banks of the Mersey were inhabited by a wide variety of wildlife. Red squirrels, deer, hedgehogs, foxes and sheep wandered freely over the pastures and marshlands. In the fresh waters of nearby springs, streams and lagoons, the variety of fish, geese, ducks and swans was unparalleled, while the beaches lining the foreshore played host to everything from shrimps to dolphins and seals.

When man realised the benefits of life on the banks of this wide and free-flowing river, fishing villages, farms and ferries were created to serve man’s needs. A wide diversity of natural resources offered themselves to the growing civilisation. The Romans occupied these shores for 300 years, leaving behind many descendants as well as linguistic and cultural benefits.

Towns, boroughs, holiday resorts and commercial cities gradually evolved. Trade with other countries became of paramount importance, leading, at one stage, to the most dishonourable period in the history of Merseyside. Not only were wealthy merchants involved in the trading triangle connected with slaves, sugar, spices and manufactured goods but they were using their ill-gotten profits for purely selfish advancement. Their employees benefitted little from their own slave-like labours.

A century or so later, when the Irish Potato Famine cast thousands of desperate refugees across the Irish Sea and into Merseyside, the area almost perished under the intolerable death toll from dysentry, cholera and widespread starvation. Those who could, fled. But those who stayed added to the gene pool of the locality. They, along with many other welcome nationalities who chose to integrate with the indigenous citizens of Merseyside, contributed much to the dynamism and humour that now typifies a genuine Scouser and his ‘kissing cousins’ who live nearby. It is this noble pot-pourri of celebrities that we now celebrate and salute in Merseyside’s Own.

Cyril Abraham

1919–79

Writer of The Onedin Line and the man who once did a Beatle’s homework

The sails billow out, the waves crash against the bows and the majestic music echoes the cadences of the breaking surf. In The Onedin Line, one of the most popular BBC drama series of all time, the SS Charlotte Rhodes leaves the Mersey Estuary and puts to sea once more. Armchair voyagers relax in the knowledge that the next hour will bring storms, rivalry, romance, double-dealing, danger and ultimate success. The fact that an undercurrent of genuine Victorian maritime history gives depth to the narrative, is a welcome bonus.

Set in the years between 1860 and 1886, the saga unfolds. James Onedin (Peter Gilmore) handsome yet stern and unyielding, is an impoverished sea captain. In an astute marriage of convenience, he weds a plain, older woman, Anne Webster (Anne Stallybrass, actually considerably younger than Gilmore). They come to love each other and their deep devotion plays a key role in the development of the first two series. Tragedy strikes when Anne Onedin dies in childbirth, leaving the widowed James free to pursue other romances, culminating in two further marriages in the total of eight series and ninety-one episodes.

Cyril Abraham.

The authenticity of the storylines and the historic exterior locations were highly valued by a discerning public, many of whom were ex-seagoing folk themselves. Every detail was scanned and analysed by loyal fans. Many correspondents wrote to Cyril, the creator and writer of the saga. One erstwhile sea captain claimed that he recognised the ship being used in one programme from his own experiences at sea.

‘I remember a certain distinctive scratch on the woodwork. It’s been there for as long as I can recall. How wonderful to see the real thing on the ocean again,’ he wrote. In actual fact, the interior of the ‘ship’ was a plywood set, constructed within the shell of an ex-church building, St Peter’s in Dickinson Road, Manchester. This makeshift studio was used for many drama productions as well as for quiz shows such as Call My Bluff.

The River Mersey, too was a sham. The real docks and harbour board at Birkenhead and Liverpool were now so modern, with cranes and containers visible everywhere, a substitute had to be found. Exeter and Dartmouth still retained the quaint old-fashioned appeal of bygone times, while the Welsh shorelines around Pembroke doubled convincingly for nineteenth-century Turkey and Portugal. Khachaturian’s resounding music for the ballet, Spartacus, added to the atmospheric opening titles. The acclaimed acting skills of a perfectly matched cast ensured The Onedin Line’s place in the list of top television period dramas of all time.

‘How did you get started in writing?’, ‘What did you do before?’ and ‘Where do you get your ideas?’ are the three most frequently asked questions to all authors and scriptwriters.

Before success came his way, Cyril Abraham was a Liverpool bus driver with literary ambitions. Before that he had been a Marconi wireless operator in the Merchant Navy, on ships transporting food and essential medical supplies during the Second World War. He was lucky enough to escape unscathed despite some alarming encounters in dangerous waters. Then came a spell as a ‘Bevin Boy’ down the mines at Bold Colliery. As a youth, he had trained at HMS Conway and before that he was a pupil at the Liverpool Collegiate. But the end of the war saw him at a loose end, not sure what to make of the rest of his life. As a temporary measure he joined Liverpool City Transport. At Smithdown Road bus depot, his driving instructor was Harry Harrison, a friendly man who was often ready to chat about his own life when at sea with the White Star Line. One day he said to Cyril, ‘I’m fed up with my teenage lay-about son. He doesn’t concentrate in school, he doesn’t do his homework and he’s got in with some useless gang of lads. All they do is hang around messing with guitars and drums. What use is that? How’s he going to earn a living like that?’ On another occasion, Harry came to Cyril with a school exercise book in his hand.

‘Cyril,’ he said, ‘You’re an educated feller. My youngest is at the Institute but he can’t do this homework. And I can’t make it out either. Will you have a go at it – and our kid can copy it out in his own handwriting later.’ Cyril duly obliged and there were other occasions when he was glad to help, too.

It was some years later when Cyril bumped into Harry again. When he did pass him in the street, Cyril spoke with tongue in cheek.

‘Hello Harry, how’s that no-good son of yours these days?’ Harry took it all in good humour and replied, ‘Oh, the other day he said to me, “You’ve always liked the horses, haven’t you Dad? Well here’s your birthday present. It’s the credentials for a pedigree race horse. He’ll be stabled and trained for you. You’re registered as the owner.”’

Peter Gilmore, star of The Onedin Line.

‘So you’re proud of George now that he’s one of the Fab Four, then?’ smiled Cyril and they both had a good laugh.

It was at about this time that Cyril met Joan, a Liverpool teacher. Now Cyril’s widow, Joan takes up the sequence of events:

I thought he seemed an interesting sort of chap, so I asked him what he did for a living. When he told me about his various occupations, he added that he really wanted to become a writer. ‘Why don’t you then?’ I asked.

‘Well I can’t afford a typewriter and no editors or agents will look at anything in handwriting,’ was his excuse. So I went into the city centre and looked in the window of an office supply shop. There was a notice saying, SALE – TYPEWRITERS – FOUR GUINEAS. It was the end of the month so I had hardly any cash left from my salary but I went in anyway. When I asked about the sale, the assistant said, ‘Yes, madam. Just those over there.’

‘But they’re a hideous shade of bright pink!’

‘Yes, madam. That’s why they’re reduced. No offices want pink typewriters.’

‘Well, I haven’t got four guineas on me, anyway,’ I said.

‘We have hire purchase facilities. It’s half-a-crown down and half-a-crown per week.’

So I scraped up what coins I had in my purse and gave him 5s for the first two payments. And I had to pay out some more, for ribbons, of course.

She took the typewriter to Cyril’s home and gave it to him. A week later, she asked him if he’d written anything yet.

‘I can’t,’ he said. ‘I can’t afford any paper.’

They had a friend who worked in an office. Before the days of recycling, secretaries frequently used to throw away unused sheets of paper. So each night, Joan’s friend went around all the offices in her building, found any unwanted paper and brought it home for Cyril. At last he had no excuse, so he started work. He began with short stories and articles, some of which were accepted by Australian magazines. When Cyril submitted a screenplay to the BBC, he was invited to meet Andrew Osborne in a London restaurant. He said that Cyril’s script was just what he was looking for.

‘I’ve had too many plays where the characters are just cardboard cut-outs,’ he said. ‘Your people have got real ROOTS !’ As he boomed out ROOTS, he thumped the table so hard that all the cutlery jumped up into the air then clattered onto the floor. The waiter hurried over thinking that the two men were having a row.

After contracts were signed, two high-ranking BBC executives rang Cyril to say that they were in Manchester and could they meet up? Cyril invited them to his father’s bungalow in Manley between Frodsham and Delamere Forest. Joan provided all the ingredients for a special gourmet lunch but couldn’t stay, as she was teaching. Cyril took the two producers for a business stroll through the beautiful National Trust forest. On their return, Cyril asked his father if he had cooked the meal.

‘Oh yes,’ was the reply. ‘It was delicious. I ate most of it and gave the left-overs to the dog.’ The two producers didn’t get a bite to eat – the only bite they did get was on the ankle, from the ungrateful dog. Cyril had to take them to the nearby Goshawke Pub for a liquid lunch.

Fortunately, the programmes became so successful that all was forgiven. After the series finished, Cyril then adapted the saga of the Onedin family into novels. These were translated into many different languages, the television programmes were sold all over the world and the novels became the basis for audiobooks recorded by Ulverscroft Isis Soundings and voiced by Ray Dunbobbin. When Cyril was earning four- and five-figure fees per weekly episode, his father warned him not to be rash.

‘It won’t last,’ he said, ‘I think you should go back to the buses. It’s a steady wage, with a pension and a smart uniform provided. Can the BBC match that?’

After their marriage, Joan and Cyril moved into the secluded bungalow, a converted cricket pavilion, in Manley. Liver failure, exacerbated by a fondness for alcohol, caused Cyril’s early death in 1979 but his radio plays, books and the repeats of his television programmes are a constant testament to his innate talent as a raconteur and the value of a hideous pink typewriter.

Jean Alexander

Hilda Ogden, Aunty Wainwright and a host of others

‘Stanley! I want a huge Muriel of a landscape to cover the whole of this wall!’

‘Oh aye? And I s’pose yer want a flight of plastic ducks flyin’ across it, an all?’

‘Oo, yeah. That ’ud be just pairfect. Plaster ducks an’ a Muriel. We’ll ’ave both.’

Hilda and Stan Ogden, in Coronation Street

In her autobiography, The Other Side of the Street, Jean writes that many people have asked her, ‘Who were you before you were Hilda Ogden?’

‘It is true,’ she comments, ‘that Coronation Street took up a third of my life but there was a Jean Alexander before I ever stepped into the Granada Studios and there is still a Jean Alexander since I left the programme.’

Jean was born in Toxteth, in the area where all the streets have Welsh names. She went to Granby Street School and later to St Edmund’s College. She owes her love of literature to her English Mistress, Miss Potter, ‘A brilliant teacher who had me hooked on Shakespeare by the age of fourteen.’ But Jean’s fascination with show business in general began even earlier, in a lodging house in Barrow-in-Furness. Jean’s father was working at the shipyard for a few months, so the close-knit family moved with him. Staying at the same boarding house was a dance troupe of about a dozen girls. Little Jean watched them rehearse in the backyard and then tried to copy their steps.

‘Some of the glamour which covered them like stardust,’ she says, ‘worked its way into my young heart and stayed there, hidden like a seed that is going to flower in some distant spring.’

During the Second World War, Jean was at first evacuated to Chester but this turned out to be potentially no safer than Liverpool, due to its proximity to Sealand Aerodrome where RAF pilots were trained. Sailors awaiting embarkation in Liverpool were also wandering around everywhere in Chester, so Jean soon returned home. Living at that time in a house with a cellar, used as a makeshift air-raid shelter, Jean’s pet kitten frequently acted as an air-raid early warning system. Several minutes before any siren sounded, a startled Snooky would jump up from his favourite cushion by the fire and scurry downstairs to hide under the camp bed. Sure enough, a bombing raid would always follow. Obviously Snooky had super-sensitive hearing and could accurately detect the sound of enemy aircraft even at a great distance. The family gratefully followed him, often with half-eaten meals in their hands.

In 1944, Jean went to work for the Liverpool Library Service but her acting ambitions were struggling to find an outlet. After several brief theatrical appearances and some non-acting jobs, such as wardrobe mistress at Oldham Rep, where one of the giant baskets containing costumes turned out to be also the nesting place of a huge, gingery coloured rat, Jean eventually received an invitation from Donald Bodley to join the Southport Repertory Theatre, ‘Just for a single week’s production only,’ he told her. The play, See How They Run, a popular and hilarious farce, was such a success that Jean was granted just one more week’s engagement. Seven years later, Jean was still a member of the company, having played every conceivable character in a vast variety of tragedies, comedies and classical plays. Southport had much to recommend it and Jean has enjoyed living there ever since. Then came one of Jean’s favourite periods of her career, five years at the Theatre Royal, York, where she still has friends. A short season at the Liverpool Playhouse Theatre gave her the pleasure of working with director Willard Stoker and actors Benjamin Whitrow, Caroline Blakiston and Rita Tushingham. In total, Jean had twelve years of theatre and film experience before her first appearance in Coronation Street.

Jean recalls with great affection her many years working with Bernard Youens, her ‘husband’, Stan, in Coronation Street. Her fond pet name for him was ‘Bunny’.

‘Our rapport was obvious from the outset,’ she says. They became the perfect colleagues. ‘Our method was to know the lines thoroughly, play around with them to make the very best of the script. Then go to a quiet corner to rehearse together while, at the same time, playing Scrabble and swearing vehemently if the other one made a clever move.’

‘Hilda’ always had a twinkle in her eye and such was the warmth and humour that Jean brought to her pinny-and-curler-wearing alter ego, the nation took her to their hearts. In a 1982 poll, the public voted that the most recognisable women in Britain were Queen Elizabeth II, the Queen Mother, Princess Diana and Hilda Ogden. In the 1980s, for four consecutive years Jean won the TV Times Best Actress Award and, in 1985, the Royal TV Society Best Performance. In 1987 she received Radio Merseyside’s Scouseology Trophy For Lifetime Achievement. The gossipy nosey-parker whose conversations were decorated with many endearing Malapropisms enlivened and enriched Corrie for twenty-three years. Sir Laurence Olivier adored her and formed the Hilda Ogden Appreciation Society, recruiting many other famous fans.

Jean has the capacity to learn new dialogue every day, no matter how tricky the vocabulary. Other cast members, however, often stumbled over their lines. One such was Margot Bryant, better remembered as Minnie Caldwell. She would often waffle with her words, substituting lines that the script-writers had never written, such as ‘My father had a big dog once. It was a ferret.’

When Jean finally decided to shake the past out of Hilda’s dusters, twenty million viewers shed a little tear at her farewell party in The Rover’s Return.

As Hilda Ogden moved away from Weatherfield, Jean Alexander found a fresh and highly successful phase in her career. At the BBC, the advent of Aunty Wainwright and her Aladdin’s cave of bric-a-brac breathed new life into the long-running Last of the Summer Wine. As cunning as the Artful Dodger, with her dubious deals, this devious old dear must surely have kissed the Blarney Stone. Once again, Jean invested the character with an underlying warmth that endeared her to viewers and kept them chuckling at all her wily little scams for more than twenty years. Jean now regards ‘Aunty’ as ‘my favourite role ever!’ What a happy and satisfying thing to be able to say.

Arthur Askey CBE

1900–82

‘Big-Hearted Arthur, they call me!’

Does it still exist? That old-fashioned wooden desk that once graced a classroom in the Liverpool Institute Grammar School for Boys, now the Liverpool Institute for the Performing Arts? That desk where the young Paul McCartney once sat and, by chance, noticed the carved name of a former famous pupil, Arthur Bowden Askey? Was it naughty vandalism or the creation of a show-biz relic with these two such celebrated associations? And where is it now?

Arthur Askey was born at 39 Moses Street, at the turn of the twentieth century. His father worked in the office of a firm with long connections to the importing of sugar from the West Indies. Arthur’s mother originally came from Knutsford, Cheshire, the real location of Cranford by Mrs Gaskell, filmed as a serial by the BBC.

Arthur’s accent was never of a true Scouse intonation but a tone unique to himself. Years of being the youthful lead in Isle of Wight concert parties may have influenced this popular comedian’s pronunciation, turning his catchphrase, ‘I thank you,’ into ‘Aye thang yeow,’ and making ‘Beefore your VERRIE eyes,’ and ‘Hello Pliymates,’ sound almost cockney in their wide-mouthed exuberance.

As a youngster, Arthur’s clear singing voice earned him parts in school concerts and a place in the church choir at St Michael-in-the-Hamlet. After leaving the Institute, he became a clerical assistant in the Education Department of the Liverpool City Council. In spite of poor vision, he was called up into the army towards the end of the First World War where he spent most of his time in Entertainments, keeping up morale and dispelling boredom. His popularity grew with every show.

Having natural charisma and immense vitality, he accentuated his humorous appearance with ‘Harry Potter’-style, black-rimmed glasses. He often sported a trilby hat, several sizes too small, emphasising his unusually large head and long chin on his diminutive body.

His dapper appearance and sparkling personality were ideal for silly jokes, silly songs and even sillier dances, all apparently childishly innocent but cunningly interspersed with saucy little double-entendres. During the Second World War, his satirical song, ‘It’s Really Nice to See you, Mr Hess’, and the patriotic ‘We’re Going to hang out the Washing on the Siegfried Line’, caused him to be included in a Nazi hit-list, condemning him to be shot if the Germans ever invaded Britain!

After years touring with concert parties and pantomimes, radio beckoned and Arthur teamed up with Richard Murdoch in a programme called Band Wagon. Richard – tall, elegant and urbane – was the perfect foil for cheeky little Arthur. The original scripts for Band Wagon were weak and boring, so Arthur and ‘Stinker’ Murdoch wrote their own, vastly funnier material. This eventually led to the crazy comedy in which the two supposedly shared a flat at the top of Broadcasting House. As this was radio, other characters could be anything from talking pigeons and a goat to a girl named Nausea and her mother, Mrs Bagwash.

Television was the next step. Arthur was a natural. His timing and facial expressions were faultless and, talking straight to camera, he endeared himself to even wider audiences. When interviewed and asked if he had to find new jokes for television, his candid admission, ‘No, I just rearrange them into a different order!’ was delivered with such an engaging twinkle, it became a joke in itself.

In real life, too, he was always warm and friendly. His marriage was happy. He and his wife, Elizabeth, had one daughter, Anthea, who eventually became an actress.

During the 1970s, the talent show New Faces, hosted by Mickie Most and song writer Tony Hatch, also included the kindly, big-hearted Arthur. He was the ‘nice’ one who always had an encouraging word for the hopefuls.

Several films including Charlie’s Aunt and The Ghost Train, completed Arthur’s long catalogue of every form of entertainment, prompting pop producer Pete Waterman to buy the rights to every one of Askey’s films.

After his final film, Night Nurse, ill health forced Arthur to retire. Eventually, circulatory problems necessitated the amputation of both legs. Even at the age of eighty-two, his popularity had not waned. Succeeding generations of comedians were still learning from his wide-ranging successes. His name lives on as one of the most endearing and enduring personalities of the Liverpool comedy scene.

Dame Beryl Bainbridge

1932/33/34(?)–2010

Actress, author – ‘the Booker Bridesmaid’

The actual date of Beryl Bainbridge’s birth is, fittingly for the author of such strange and perplexing fiction, shrouded in mystery – but not so the rest of her life, as many of her early novels draw upon her personal experiences, her childhood, her various employments and her emotional entanglements.

The most important fact about her is her unique talent and style of prose. Eighteen books, many weirdly humorous novels and a handful of historical chronicles brought her plaudits and prizes, including the Guardian Literary Prize and the Whitbread Award, although the Man Booker Prize continually eluded her. In spite of five of her books being nominated over a period of years, she never actually won the Booker Prize, a reminder of the phrase, ‘Always a bridesmaid, never the bride.’ Accustomed from an early age to disappointments and frustrations, Beryl bore the results stoically, comforted by nicotine and alcohol. At parties, she was famous for her heavy smoking, drinking and falling over.