9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

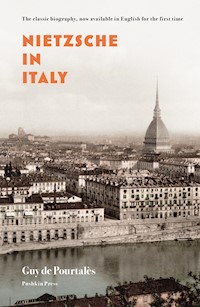

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

For fifteen years, after his first visit to the country in1876, Nietzsche was repeatedly and irresistibly drawn back to Italy's climate and lifestyle. It was there that he composed his most famous works, including Thus Spake Zarathustra and Ecce Homo.This classic biography follows the troubled philosopher from Rome, to Florence, via Venice, Sorrento, Genoa, Sicily and finally to the tragic denouement in Turin, the city in which Nietzsche found a final measure of contentment before his irretrievable collapse. Endlessly fascinating and highly readable, Nietzsche in Italy will enthral anyone interested in Nietzsche's relationship with the country that enriched his soul more than any other.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

NIETZSCHEin ITALY

Guy de Pourtalès

Edited, translated and with an introduction by Will Stone

PUSHKIN PRESS

Contents

Introduction

Pourtalès was forty-eight years old when he wrote Nietzsche in Italy. Midway between his musical biographies, the Nietzsche book, essentially a protracted essay evenly sliced into brief chapters, sits slightly askew from them, seeming a little like the black sheep, the less visible maverick in the well-oiled sequence of audience-guaranteed works on composers to either side. Perhaps this is why it failed to be picked up by English language translators at the time, unlike the venerable Liszt and Chopin tomes. Yet in contrast to the more long legged “romantic” biographies, the smaller Nietzsche in Italy sparkles with a timeless quality some ninety years on, and despite its age, often feels light footed and impressionistic, suggestive and enquiring rather than over assured, its seams stretched with conviction. Scepticism and deliberation over academic authoritarianism. Pourtalès, the descendent “Good European”, is both in awe of this titanic spirit and feels genuine sympathy for the necessary suffering of the body that bears it; thus the reader travels on under the sign of a noble humanism. Pourtalès seeks to paint an image of an exceptional mind stretched to its limits trapped within a living being steadily transformed into a position of historical uniqueness by that being’s own strength 8of will and always against the odds. For Pourtalès, Nietzsche is both liberated and constricted by a self-imposed mission that becomes more messianic as he finds himself alone in unexplored terrain and there accrues revelatory insight. Reality and its wearisome imp of the perverse is his daily curse and a body which frustratingly won’t give him enough hours of relative health to distil that intellectual firewater from the mind. We witness with unease and increasing sympathy Nietzsche’s restless journeying, the mental load borne from the attempt to radically adjust the restricted sight of an age. We are made painfully aware of this exceptionally lucid individual’s precarious existence in an inwardly degenerating society, advancing scientifically and materialistically, but retarded psychologically and spiritually by clinging to handed down Christianity and “foreground conclusions”. The drums of nationalism grow ever louder as the philosopher leans ever closer to the page. Nietzsche is a European traveller and seeker by philosophic heritage, self-determination, cultural wont, peripatetic inclinations and climate induced exile, while Pourtalès shadows his master in all these, the robustness of his pan-Europeanism underpinned by his ease of movement between German, French, English and Swiss language and culture. Author and subject share a common heritage, a perceived future which is irrevocably European, where borders define neighbouring cultures eager to converse and reciprocate. The confinement characterized by militarism and nationalism are anathema to them. Neither man is prepared to pace the drab corridors of monolingualism. Movement in a free space is everything.

Pourtalès ensures we follow the relentless combatant at a discrete distance, though we still have him in plain sight, as he 9is gradually acted on by the restorative climate and atmosphere of the South, antipode to the Northern darkness of Germany (a trope set in motion by Goethe and his Journey to Italy). We witness Nietzsche at successive stages of his development as the myopic visitor follows his travelling trunk onto the platforms of his preferred Italian cities. Naturally Pourtalès includes the major dislocating events and their aftermath; the unsavoury break with Lou Salomé after the marriage snub, the disenchantment and severance with Wagner, the unexpected sanctuary of a quiet quarter of Venice and Bizet’s Carmen, on to the downfall in Turin so wilfully dramatized in the public imagination. Yet one senses whether in Genoa or Messina, in Rapallo or Venice, in Sorrento or Turin, we are rather awkwardly waiting in the wings to see how long this lonely ‘professor’ can survive with his dwindling reserves of air as the expected literary response fails to come. For Pourtalès then, Nietzsche’s Italy is a series of chronologically linked stations of necessary regeneration and subsequent creative breakthroughs. This idea has of course been taken on by a number of authors and Nietzsche scholars since then, and details have been necessarily fleshed out, but Pourtalès was surely the first to bring these Italian ports of call together, to construct the map of topographic salvation in a way which shows the recurring holistic attributes such locations offered Nietzsche, who let us not forget habitually returned to those places which had served him well in the past, hoping for similar deliverance, or because distracted by thought or some symptom of his sickness he clambered onto the wrong train.

Yet even the casual observer can see that Pourtalès’ account is a little idiosyncratic, selective rather than comprehensive, and focuses more heavily on Nietzsche’s experiences in Venice, 10Genoa and Sorrento, whilst Lake Orta for example gets barely a mention. Although he mentions Nietzsche, Paul Rée, Lou Salomé and her mother travelling there before Lucerne and thence Tribschen in the spring of 1882, there is no mention of the time spent in Orta, most significantly the fabled kiss between Nietzsche and Salomé on the terrace of the romantic Sacre Monte above the lake, perhaps suggesting something more than intellectual admiration on her part and which Salomé, mercurial to the end, later did little to deny or confirm. “Whether I kissed Nietzsche on the Sacre Monte I do not know now”. The stricken Nietzsche looked back to the Orta days with Salomé as the zenith of their relationship, when a definitive union seemed possible between two increasingly interweaving souls walking together, batting thoughts back and forth, within the romantic ambiance of the medieval lakeside town, on the tiny island of St Giulio with its mysterious convent squeezed in atop a rock, in the pine woods around the Sacre Monte studded with ancient frescoed chapels. Later, as he painfully watched Salomé pull away, Nietzsche defensively attributed characteristics of spite and cunning to the woman who rejected his hand, gruffly declaring ‘the Lou of Orta was a different being’. Why Pourtalès omitted this legendary moment in the Nietzsche Salomé story nevertheless remains unexplained. Perhaps he felt its resonant ambiguity an unnecessary distraction.

This piece would not be complete without mentioning one of Pourtalès’ key correspondents, whose shadow hovers over this essay because of his own text on Nietzsche published four years earlier in 1925. Stefan Zweig’s essay “Nietzsche”, the third part of The Struggle with the Daemon: Hölderlin, Kleist and Nietzsche could well have informed or inspired Nietzsche in11Italy. Did Pourtalès read Zweig’s work? Potentially, probably, presumably… the two were working in similar fields, both were engaged in monographs and biographies, they respected each other and corresponded. But does it really matter, for though they are both devotional tributes to a heroic intellectual struggle, they are quite different books. Zweig’s “Nietzsche” excels in its compelling portrayal of Nietzsche’s physical sickness and apartness, his lonely, pauperized existence restlessly moving between down at heel pensions in the Alps and coastal resorts and back to his writerly base, the rented first floor room in the Durisch house at Sils Maria, plagued by no reply from the world below the Engadine plateau. In contrast the primary focus for Pourtalès is the author’s biographical leitmotif; music, as crucial presence and life force, as inspirational backdrop and inward filament running through Nietzsche’s mental universe, intermittently glowing and powering up the faltering generator. The soon to be realized Wagner book was simmering away in Pourtalès’ mind when he wrote Nietzsche in Italy, but it is here he makes the first inroads, performs the groundwork and gathers the required momentum. After reading Pourtalès’ little book one can certainly understand better not only the way the releasing power of music served to reinvigorate, even recalibrate Nietzsche’s mind, but how a particular arrangement of notes literally held him back from the abyss, from the destruction he fully expected, most importantly just long enough to carve out those dark-veined yet shimmering last works, those stars formed from a point of origin which no longer exists but whose long-travelled light we see so vividly now.

will stone exmoor, may 2022

Cast of Characters

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE (1844–1900)

German philosopher, philologist, classical scholar, poet, composer and cultural critic who attempted to reveal the false values that underlie Western societies clinging to outmoded religious concepts and to provide a new existential framework for an idealized thinking man of the future, the free spirit.

LOU ANDREAS SALOMÉ (1861–1937)

Russian-born intellectual, poet and essayist, later psychoanalyst, who had relationships with some of the most influential artistic figures of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These included Nietzsche, whose marriage proposal she turned down, and later the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, whom she accompanied on lengthy trips to Russia and continued to support and counsel until his death in 1926. 14

PAUL RÉE (1849–1901)

German author, physician and philosopher who met Nietzsche in the summer of 1873. Rée, then a doctor of law and five years younger than Nietzsche, had already written a dissertation in Latin on Aristotle’s Ethics. They shared a mutual interest in the French moralists and Rée’s thought later influenced Nietzsche during his middle period from Human, All Too Human (1878). Whatever level of friendship existed between Nietzsche and Rée following the former’s ill-starred marriage proposal to Salomé, it could not survive the aftermath.

MALWIDA VON MEYSENBUG (1816–1903)

German writer best known for her Memories of an Idealist, the first volume of which was published anonymously in 1869, as well as her friendships with intellectual figures such as Nietzsche and Wagner. She invited Rée and Nietzsche to the Villa Rubinacci in Sorrento in the autumn of 1876, a moment of transformation for Nietzsche and the genesis of his later philosophy. Von Meysenbug was the first woman to be nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1901.

RICHARD WAGNER (1813–83)

German composer, conductor and theatre director known primarily for his operas, who towers over nineteenth-century music and culture. Wagner is famous as an innovator, whose 15groundbreaking methodology changed the course of musical history. His most ambitious project was the monumental fifteen-hour Ring cycle. Something of a controversial figure today, Wagner’s legacy, however impressive, has been tarnished by his antisemitism.

COSIMA WAGNER (1837–1930)

Wife of the composer Richard Wagner and illegitimate daughter of the Hungarian pianist and composer Franz Liszt. She married the aristocratic German musician Hans von Bülow in 1857 but divorced him in 1870, having spent a year living with Wagner at Tribschen. Later that year she married Wagner and bore him three children: Isolde, Eva and Siegfried. After Richard’s death in 1883 she dedicated the rest of her life to maintaining the Wagner cult. Her diaries (1869–83) provide a trove of detail on the composer’s life and thought.

PETER GAST (1854–1918)

Johann Heinrich Köselitz, German author and composer, was given the pseudonym of Peter Gast by Nietzsche. Their friendship developed during Nietzsche’s time in Basel and Gast would read to the half-blind professor and take dictation. Köselitz was a key figure in the preparation of Nietzsche’s works and devoted himself to furthering Nietzsche’s exposure. For his part, Nietzsche, in a bid to throw off Wagner’s Northern trappings and embrace the Southern style, somewhat overestimated Köselitz’s 16talent as a musician. From 1899 to 1909 Köselitz was conscripted into Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche’s “Nietzsche-Archiv” in Weimar. Always suspicious of the motives of the chief “curator”, he left in 1909, tainted by collusion, after he assisted in the publishing of the highly selective edition of The Will to Power.

ELISABETH FÖRSTER-NIETZSCHE (1846–1935)

Formerly close to Nietzsche and two years his junior, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche was his sister. Elisabeth and Friedrich became more distanced following her marriage to Bernhard Förster, a publicly visible German nationalist and antisemite, in 1885. To her brother’s horror, they established a racially sanctioned German colony, “Nueva Germania” in Paraguay, in 1887. After her tormented husband’s suicide in 1889, she continued to run the colony with an iron fist. Returning to Germany directionless in 1893, she had a lucky break. Finding her brother now an invalid whose writings were catching fire across Europe, she swiftly adopted the role of safeguarding his legacy and thus was able to edit his writings in ways which furthered her own nefarious political and racial convictions.