Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

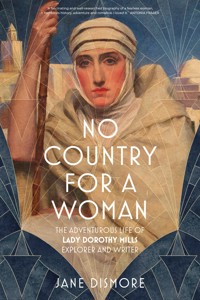

'A fascinating and well-researched biography of a fearless woman, it combines history, adventure and romance. I loved it.' - Lady Antonia Fraser Lady Dorothy 'Dolly' Mills was a trailblazer, whose larger-than-life personality led her to extraordinary adventures. Born in 1889 into the Walpole family, who were eminent in political and literary spheres, Dolly defied the constraints of her upper-class upbringing by marrying a poor army captain, prompting her disinheritance. From becoming the first English woman in Timbuktu she forged a reputation as one of the most renowned explorers in West Africa and beyond, travelling deep into Venezuela and the Middle East – territories often considered the preserve of men – breaking the mould and challenging her background and the expectations of her gender. Dolly wrote acclaimed travel books, documenting remote places and peoples, capturing history in the making. By the 1930s, she was the best-known female explorer, appearing on platforms and in books alongside prominent men. She was elected as an early female Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and was a strong advocate for women in the field, leaving a bequest for women explorers on her death in 1959. A feminist with unorthodox views which ultimately cost her her marriage, Dolly also wrote bold novels and incisive features for women. Despite life-changing obstacles, she never lost her love of donning a glamorous frock and downing a cocktail. No Country For a Woman is the first book about the life of the best-known female explorer, set against the backdrop of the decadent Jazz Age, and will captivate not only those who are fans of other famous explorers but also curious readers, interested in the lives of fearless women.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 446

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Jane Dismore, 2025

The right of Jane Dismore to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 615 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

CONTENTS

Introduction

Prelude – Cast into the Darkness

1 Only a Girl

2 A Different Drummer

3 The Debutante

4 The Call of the Wild

5 Where all Roads Lead

6 Monster Woman

7 A Middle Eastern Melting Pot

8 From Leopard Men to Devil Worshippers

9 Bloody Jackals

10 The Outlier

11 Setbacks

12 Along the Orinoco

13 Towards Sunset

Epilogue

Appendix

Notes

Acknowledgements

Sources

INTRODUCTION

When Lady Dorothy Mills was a young girl, a female relative told her she would never be beautiful, so she had better be interesting – and as a bold, determined woman from one of Britain’s oldest political and literary families, the Walpoles, she became just that. Rather than following the path expected of her class and sex, she took control of her destiny to become the most popular female explorer of the time. With a deep interest in people and an insatiable curiosity about the world, she turned her experiences into highly acclaimed travel books and escapist novels and in the 1920s and 1930s was seldom out of the public eye; newspaper readers also enjoyed her feminist features at a time when women were finding new freedoms in the period between the two world wars.

How extraordinary, then, that this is the first book about her life. Today, her name seldom comes to mind when women travellers are discussed, even though she journeyed alone (and separately from her husband) during the volatile period following the Great War, to countries where European women had rarely, if ever, ventured. Sometimes, she was the first white woman to do so, enduring physical and mental challenges and life-threatening hazards. A woman of her time in certain ways, ahead of it in others, her life provides a prism through which we can see and understand better the issues of the day – race, gender, colonialism, class – while also reminding us of what draws us together rather than what divides us.

So, why is she not better known? She has been referred to, often sketchily, even inaccurately, in compendiums. Her books were relied on during her lifetime as a source of information and, more recently, for academic study, but now are out of print, her passionate prose and self-deprecating humour accessible only to those who know of their existence and are willing to hunt them down. She has devoted fans on the internet who know a little about her life but cannot find more. It is as though something has conspired to keep her out of history. Ultimately, though, the memory of a person can be kept alight only by the living, and if no one does that, there is only darkness.

Born into the patriarchal society of the late Victorian era, she determined not to be limited by it or overlooked. ‘I must be something,’ she wrote. She certainly was, and I wanted to make her, like the woman in her novel Phoenix, rise again.

It has not been an easy task. That she was not publicity-shy and was prolific in her writing have been gifts in helping to piece together a life in which she underwent a metamorphosis from a ‘useless young creature’ to an inspiration for twentieth-century women, even while affected by personal tribulations. To enable me to write this book, I am deeply grateful to the historian and biographer Antonia Fraser, whose interest in my subject led to my receiving her eponymous award (in the form of an Authors’ Foundation Grant), administered by the Society of Authors. Lady Dorothy Mills can live once more.

PRELUDE

CAST INTO THE DARKNESS

By June 1916, the grimness of the Great War was changing the face of Britain’s cities. Since the first air raids, a year earlier, London’s Underground stations were becoming unofficial shelters for thousands and locals were wearily becoming accustomed to the dreary inevitability of blackouts. Conscription was newly in force, prompting angry demonstrations in Trafalgar Square. But every now and then a reminder of life as it was and might be again, of hope triumphing over misery, would appear above the parapet and give people a reason to smile.

On 22 June, a vision in a gold and white wedding gown paused outside St Paul’s Church, Knightsbridge, to let the sunlight catch the gold leaves of her headdress and smile a greeting to reporters, before joining the waiting groom. Lady Dorothy Rachel Melissa Walpole, aged 27, petite and bold, wanted to make a statement to those naysayers who held little hope for her happiness. She proudly claimed to be the first London bride to wear a gold wedding dress, her decision typical of her originality, even though the cost meant it would be her only evening frock for the foreseeable future other than those she made herself.

If Dolly, as she was known, was a bright display, her fiancé was a more sober reminder of the times. Captain Arthur Frederick Hobart Mills, nearly 29, wore the uniform of his regiment, the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry. At 6ft 2in tall, with dark brown hair and heavy-lidded brown eyes, he was a handsome figure and part of the British Expeditionary Force in France until he was shot in his right ankle, an incident he described in his recently published book, With My Regiment,1 and which had seen him invalided back to England.

Not only was the wedding dress unusual, but the ceremony was too, in which tradition played little part. Their engagement had been announced just a couple of weeks earlier and no wedding invitations were issued; instead, The Times announced simply that all their friends were welcome at the church. Unusually, the bride had no bridesmaids, a decision that was unlikely to offend anyone. When Dolly was 4, her only sibling, Horatio, had died at the age of 2 and she ‘tactlessly remained the only child’.2

The groom’s best man was a cousin and fellow officer, and on that side too, there was no one who could reasonably be upset by not having a role to play. His parents’ only child, Arthur was 2 when his mother died; his father, the Reverend Barton Reginald Vaughan Mills, had remarried and now Arthur had three half-siblings, George, Agnes and Violet, all of whom were present.3

The ring that Arthur placed on Dolly’s finger was fashioned not from traditional gold but from lead, taken from the bullet that had wounded him. After the ceremony, there was no formal reception, although that was not unusual for wartime. Apart from Dolly’s dress, the simplicity of the occasion was commended by the newspapers as being a splendid example of frugality in the face of an uncertain wartime economy.

While the event was covered by much of the press, a further break with tradition was glossed over, if it was mentioned at all – the fact that the bride was given away, not by her father but by Arthur’s uncle.4 It was not that her father was dead, far from it, but Robert Horace Walpole, 5th Earl of Orford, did not approve of his daughter’s choice of spouse, and Dolly could not look to her mother, Louise, for support, for she had died too soon.

The real reason for the simplicity of the wedding had less to do with sensible wartime husbandry than the fact that the earl would not pay for it. Worse than that, he had disinherited Dolly. The groom’s lack of a title had likely not impressed him, yet Arthur was from an aristocratic family. His late mother, Lady Catherine Mary Valentia Hobart Hampden, was a sister of the 7th Earl of Buckinghamshire and Arthur’s great-grandfather had been the 6th Earl. In the county of Norfolk, where the Walpoles and the Hobart Hampdens had owned estates for generations, the families were practically neighbours. From the age of 13, Arthur had been educated at Wellington College, a highly respected and forward-looking private school in Berkshire. If it was of any relevance to Dolly’s future happiness, his father was the grandson of a baronet and his stepmother the daughter of a Scottish peer.

But for the Earl of Orford, whose ancestors included Britain’s first prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole, and his son, the literary giant Horace Walpole, known as much for his eccentric house, Strawberry Hill, as for the first gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto, it seems that Captain Mills, in a family to which Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson had also belonged, had insufficient status or prospects. Certainly, Arthur’s financial position played a major part in the earl’s disapproval. As Dolly explained:

I fell in love, with a young man possessing most of the world’s assets except money. But that ‘Except’ had a capital ‘E.’ It was the one unforgivable sin, and was visited with everything old-fashioned and unpleasant that nothing but the Inquisition or an old-fashioned family could have devised. Marriage or disinheritance, that was the choice that lay before me, exacerbated by the advent of the Great War.5

Three years of ‘family warfare’ had preceded her wedding, ending in what she called a draw: on the one hand, she had done what she had intended, on the other, she was ‘definitely cast into utter darkness, to become the Outlier that I have ever since remained’. Her marriage was a brave move on her part: ‘I had no trousseau, we had no prospects and no money, scarcely enough even to pay for the wedding celebrations.’6 Her first novel, Card Houses, was to be published a few months after the wedding,7 but there was no telling yet how well it might sell.

Dolly had ignored the advice of those who recommended a registry office, choosing instead a church wedding, ‘and a fashionable one too’, so that if it came to it, it would be her ‘last defiance to a sceptical world’. Having never arranged a wedding before, and with no one to help her, she was desperately tired on the day but considered it well worth the trouble and money it had cost, ‘for it proved even an Outlier has friends and well wishers angelic in their kindness and good will’.8

Indeed, the earl’s attitude had not deterred the attendance of around 100 family members and friends, mostly from the upper echelons of society. Arthur’s family was well represented, with his other uncle, the Earl of Buckinghamshire, heading the maternal side, while a good number of Walpole relatives supported Dolly. Among them were Ralph and Meresia Nevill, two of the children of her late great-aunt Lady Dorothy Fanny Nevill. Another colourful and clever Walpole, she had survived the scandal of being caught in 1847 with a notorious rake who refused to marry her, hurriedly marrying instead her much older but kindly cousin, Reginald Nevill, and becoming a multi-talented and well-known figure in Victorian society, even though the Queen herself banished her from court.

The creatives and eccentrics on the Walpole side of the family gave Dolly an interesting heritage and a wealth of anecdotes, which made her an amusing raconteur. Both her parents were avid travellers, taking their daughter with them as she grew older and showing her a fascinating world which expanded her already curious mind. Her French-educated mother, Louise Melissa Corbin, was the daughter of American mining and railroad magnate Daniel Chase Corbin, whom Dolly visited as a child and came to love the USA as her second home. ‘The great expanse of the Far West, the grizzly bear in the Yellowstone Park […] the war dances of Red Indians,’ she recalled, ‘the Mormons of Salt Lake City […] stories of hold-ups in the newspapers […] all these added fuel to the youthful fire of adventure.’9

This love of travel, combined with her literary ability, would prove to be a lifeline. In their first year of marriage, she had what she called her ‘first taste of the economic problem’. Despite her burgeoning talent, including the publication of her first poem when she was in her teens, she had been expected to marry well, as were most young women of her background, without the need to worry about ‘petty household and personal economies and makeshifts’, and she was raised for that destiny. She had never learned how to do her hair without her maid or how to mend holes in her stockings. Her first attempt to lace up her own boots gave her ‘a headache and an intense desire to cry’. ‘In fact,’ she admitted, ‘never had there been such a useless young creature, till necessity turned me into a very fair Jack-of-all-trades.’10

When Arthur rejoined the war to serve in the Palestinian campaign, Dolly faced grim months of financial worry and ‘grinding anxiety in a world where nothing seemed stable, where the future did not bear dwelling on’. She soon acknowledged that she did not have it in her ‘to remain placidly in the background of life as “just” the wife of a poor man, however charming or clever he might be’. She also became increasingly aware that her ‘purely decorative upbringing’ had left her ill equipped to contribute usefully, and she saw other young women doing heroic things at home and in France. ‘Something hammered insistently in my head that I must do something,’ she wrote, ‘have some money, live life to the full, must be something.’11

Continuing family discord exacerbated her anxiety. In September 1917, her 63-year-old father, determined to secure a male heir, took a second wife. The pretty daughter of a country vicar, at 25 Emily Gladys Oakes was three years younger than her stepdaughter. It would not be long before Dolly came to a realisation: ‘I was not to be reinstated among my own kind […] I was an Outlier from my tribe.’12 Little wonder that she determined to make a mark on her own terms in a predominantly male world that had changed little since she was born.

1

ONLY A GIRL

‘The second little disappointment tonight.’1 The doctor who uttered these words as he delivered Dolly on 11 March 1889 was fully aware of the expectations of aristocratic clients like her father. No doubt Robert Walpole congratulated his wife on the safe delivery of their first child, born ten months after their marriage, but really, it was a boy he wanted. Walpole himself was heir to his uncle, the 4th Earl of Orford, by virtue of the earl’s lack of a legitimate son. While his wife had given him two very capable daughters, his only son was the result of his adulterous relationship with the married Countess of Lincoln (a highly scandalous and ultimately unhappy affair), and therefore could not inherit.

England’s class structure and the customs concerning aristocratic inheritance were a concept that was alien to Dolly’s American mother, Louise, but one with which, on meeting Walpole, she had necessarily become acquainted. Not that everything in her new life was unfamiliar to her. Louise was the daughter of the immensely wealthy Daniel Chase Corbin who, after success in mining and banking, had recently joined his brother in the railroad business, building his first railway at a time of major expansion in the USA. As such, she was no stranger to the advantages that money conferred or the divisive social codes created by those who considered themselves the cream of American society, however meritorious they liked to think it was.

When Louise was 9, Corbin sent her and her younger sister, Mary, to live in Europe with their mother, Louisa; while his daughters’ horizons would be expanded, the main reason was his wife’s poor health. Louise was educated in Germany, then France, where Mrs Corbin took an apartment on the Champs-Élysées in Paris and embraced the culture. There, Louise took her exams and showed particular proficiency in French, German and music; maths was more arduous, and saw her having to get up at dawn to keep abreast of the work.

The contents of a daybook Louise owned before her marriage give a glimpse of the happy sociability of her young life. Corbin started the book off for her in April 1885, when she was 18, with a note of fatherly advice: ‘Be polite to your equals, kind to your inferiors and always honest and true.’2

Tributes to Louise included a love letter in French, ‘un souvenir d’amour’ from a smitten Georges Roussel in August 1886. Exquisite miniature artworks – watercolours and pen and ink drawings – by friends who were not professionals but who had learned enough of the genteel art to leave their affectionate mark, depict a shared place, a fond memory, a joke. A sketch by a female friend shows a young woman at sea in a boat whose sails are giant butterflies controlled by a handsome swain. A charming ink drawing by Louis L. Odero, dated September 1885, depicts a group of young men and women enjoying outdoor pursuits among the mountains of Glion, Switzerland, playing tennis and croquet or linking hands as they help each other up a slope, overlooked by the elegant Victoria Hotel. A British Cabinet minister’s painting of a country cottage in September 1887 is accompanied by a letter promising Louise he will complete it if, on his return, he finds her still at Inverlochy Castle in the Scottish Highlands, where they were guests of Lord and Lady Abinger.

An amusing sketch painted that month, also of Scotland, shows two women on horseback confidently riding side-saddle up Ben Nevis, along a narrow ridge with a precarious drop, while a man hangs on to the tail of the second horse and is pulled along; Louise was a devotee of riding and most outdoor activities, a love she would pass on to her daughter. On the lochs, she honed her skills in angling, reflected in a little watercolour by ‘CB’, probably Clifford Bingham, a popular poet whose offering ‘For Want of You’ also graces her book. But any young man who dreamed of winning the heart of the pretty, talented – and very wealthy – Miss Corbin would have his hopes dashed when in January 1888, aged 21, she became engaged to Robert Horace Walpole, twelve years her senior.

They had met just four months earlier at that Inverlochy house party, at which their hostess was delighted to pair them. Like Louise, Lady Abinger was American, the daughter of a commodore in the US Navy. As Helen Magruder, she had met Lord Abinger in Canada, where he was stationed with his Scottish regiment, and married him in 1863, becoming one of the first Americans to marry into the British peerage; her arrival in society was truly confirmed when Queen Victoria stayed at their castle ten years later. Happy in her position, she saw the opportunity to help a fellow countrywoman find hers.

Walpole was not a tall or particularly distinguished-looking man, but he must have presented a dashing persona to Louise. Like his late father, Commander Hon. Frederick Walpole, and their ancestor, Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson, he had enjoyed an eventful career in the Royal Navy, beginning at the age of 14. At a time when it was conducting its crusade against the slave trade, his adventures included being shipwrecked for three months in 1871 on St Paul’s Island in the Indian Ocean and surviving on gulls’ eggs and seaweed. During the Russo-Turkish War he was aide-de-camp to Suleiman Pasha and, on leaving the Royal Navy as a lieutenant, aged 24, he was attached to the Earl of Rosslyn’s Special Embassy to attend the marriage of King Alfonso XII of Spain. That was followed by his appointment as private secretary and later attaché to his relation, Sir Henry Drummond Wolff, accompanying him to Egypt in 1886 when Wolff was High Commissioner. As heir to the earldom of Orford, his prospects were promising and the title historical, having been created for Sir Robert Walpole, Britain’s first prime minister in the early eighteenth century. He was also a keen traveller and proficient angler, both of which he had in common with Louise.

They married in May 1888 at the British Embassy Chapel in Paris. Five years later, Louise would find herself (along with her friend, Lady Abinger) in a list in the New York Times headlined, ‘HAVE FOUND HUSBANDS ABROAD: American Women Who Have Given Their Hearts and Money to Foreigners’. It began, ‘It has been roughly estimated that English noblemen alone have captured by marriage with American women, in round numbers $50,000,000 of enviable American cash.’3 In a way the Walpoles would doubtless consider most vulgar, the list attributed to most of the ladies specific amounts they apparently took to England, although Louise escaped that scrutiny. Nevertheless, it is most likely that Corbin’s money played a significant part in her future mother-in-law’s keenness to acquire her as a daughter-in-law.

Louise would discover that the widowed Laura Sophia Walpole was a formidable presence in the lives of her eldest son, his older sister, Amye Rachel (by marriage, the Viscountess Canterbury), and their younger brother, Clare Horatio, who, having quickly abandoned a naval career, joined the army, left that too, then married into an academic American family and lived in Virginia. Their Walpole ancestors had acquired vast estates in the heavily rural county of Norfolk in the east of England, where they built great mansions to reflect their status and wealth, most famously Houghton Hall, built in the 1720s for Prime Minister Sir Robert.4

Not to be outdone, Sir Robert’s younger brother, Horatio – Dolly’s four times great-grandfather – who was a diplomat and Whig politician, built another impressive Norfolk pile, Wolterton.5 He also bought nearby Mannington, a thirteenth-century manor house with a moat and sunken gardens, while his nephew, Horace, the famed gothic author and Georgian man of letters, was building his white castellated fantasy, Strawberry Hill, in Twickenham, west London, which is still cherished by the public today.

As far as property was concerned, the family looked impressive on paper. However, when Louise and Walpole married in 1888, England was in the middle of an agricultural depression largely caused by competitive grain prices from the USA; ironically, the new accessibility of the prairies was helped by an expansion of railway building by people like D.C. Corbin. As a result, many of England’s landowners found themselves asset rich but cash poor.

In addition, some of the Walpole houses had been desecrated by the owners themselves. Sir Robert’s grandson, George, who inherited Houghton Hall, suffered from mental instability, fell badly into debt and sold its vast art collection to Catherine the Great of Russia.

Dolly’s great-grandfather, Horatio, the 3rd Earl of Orford, liked to mess around with his surroundings. At Wolterton, he pulled down walls and changed windows, not always for the better, and replaced classic eighteenth-century furniture with modern Victorian, while disposing of artwork he disliked. He also hated the railways, preferring to make the long and uncomfortable carriage drive to London, and did everything he could to stop them coming near the house; his daughter, Lady Dorothy Nevill (Dolly’s great-aunt), said it was ‘a short-sighted policy and no good for the estate in the end’.6 His son Frederick, Dolly’s grandfather, who on leaving the Royal Navy became a Norfolk MP, bought a magnificent Elizabethan manor house, Rainthorpe Hall, where Dolly’s father and his siblings were born; however, after Frederick’s early death in 1876, his widow Laura sold the house and its contents, which included fine Jacobean and Chippendale furniture.

Nevertheless, when Louise and Walpole returned to England after their honeymoon, they had at least two residences available to them, in country and town: Waborne (or Weybourne) Hall in Norfolk, owned by his uncle who, after the end of his caper with the Countess of Lincoln was living in seclusion in London; and the house into which Dolly was born, 4 Queen’s Gate Terrace in South Kensington.

As was customary, D.C. Corbin had set up a marriage settlement for his daughter; in doing so, he may also have had an eye to protecting her from Walpole’s past. In November 1888, six months after their wedding, the hearing began at the High Court in London of a case brought against Walpole by a German governess, Valery Wiedemann. She was suing him for breach of promise of marriage and libel, for which she sought damages of £10,000. When Walpole met Louise, he may not have thought it necessary to share with her the details of his unfortunate liaison with Miss Wiedemann, for although she had first started court proceedings against him in 1883, after giving birth to a child she alleged was his, the case had lapsed. Besides, he and the governess had met in a faraway place when he was unattached. But if Louise did not already know all this when she agreed to marry him, she soon found out.

Wiedemann had reappeared in Walpole’s orbit when she heard of his engagement. Between January and May 1888, she wrote to him, to D.C. Corbin and three times to Louise, telling her of the child, which she said was living. Wiedemann also defaced a picture of Louise from LIFE magazine and sent it to her, saying she was dishonourable for becoming engaged to a man who was promised to another. Her greatest wrath was reserved for Laura Walpole, who she blamed for causing her son to break his promise. In one of at least six postcards to her, Wiedemann wrote, ‘You know that I must curse you from the bottom of my heart […] for the endless suffering you have brought over me […] I shall meet you once, and you will hear my curse.’7 She also stalked Laura’s house in Park Lane, London, and damaged the door, believing Walpole to be there.

As the hearing in November approached, the story was everywhere in the press, featuring as it did a member of such a well-known family. At the same time, it took a bold woman to sue for breach of promise, since her personal details would be bandied about in public. The undisputed facts were that Wiedemann (a good-looking woman a head taller than Walpole) had met him in 1881 in Constantinople, where she was working as a governess to the children of a hotel owner and Walpole was living on an allowance from his mother. They got to know each other and slept together. Beyond that, the facts were largely contentious.

The essence of her claim was that she had allowed herself to be seduced under a degree of violence and a promise of marriage and that Walpole had given her his signet ring (which was in her possession) and promised to take her to England and marry her within a few months. Walpole denied any such promise or violence, although did give her money so she could get to England.

Wiedemann went to Cannes, where Laura was staying, made herself known to her and, when it became clear that she would not entertain the idea of Wiedemann marrying her son, began to harass her. Walpole hired a private detective, Mr Cooke, to take Wiedemann to Paris. Her libel claim concerned what Walpole had said about her in his letter of instruction, which Cooke had foolishly shown her.

In that first hearing, Wiedemann was asked about the child she said was Walpole’s but, against advice, she continuously avoided giving a straight answer as to whether it was alive or dead. The judge threatened her with contempt of court if she did not answer and gave her the option of retiring from the case, which she chose to do. As a result, the judge directed the jury to find in favour of the defendant.

Walpole barely had time to feel relief. Ten minutes later, Wiedemann’s solicitor said she had not understood the implication of not answering the questions and they would be applying for a retrial. It was the start of a long-running nightmare for Walpole and Louise.

Such was the public sympathy for Wiedemann that a fund was set up to raise monies for her case, her champion being the London evening newspaper, the Pall Mall Gazette. Among letters it published offering money was one from ‘a very poor governess – like Miss Wiedemann herself’. She said she knew:

… what many of these ‘upper circle’ young men are like – rich, arrogant, overfed, and dissolute – and during the eighteen years I have been a governess, I have often met with young women who have been betrayed by men of this stamp, and cast adrift on the cold world with their reputation sullied – Heaven knows though it is not their fault!8

It was even reported that Queen Victoria herself, on first hearing of Miss Wiedemann’s misfortune, had sent her 25 guineas.9

The hearing to consider her application for a new trial – not even the trial itself – was set for May 1889, six months away. The humiliation of having her husband pilloried so publicly and the stress of having the case hanging over them must have put a great strain on Louise in what should have been a happy time, for she was expecting their first child in March, two months before the hearing.

No newspaper announced their daughter’s birth, which was unusual, especially for aristocratic families, but doubtless it was to avoid bringing Dolly’s existence to Wiedemann’s attention. In April, at their church in South Kensington, the baby was christened Dorothy Rachel Melissa. Dorothy was an old family name; Rachel was for her father’s aunt (the sister of Lady Dorothy Nevill), who had died too young; and Melissa was her mother’s middle name.

Two weeks later at the court hearing, Wiedemann now admitted that her child had died shortly after birth. Her solicitor persuaded the court that she had not understood the consequences of refusing to answer the questions previously and a new trial was ordered. It did not take place until June 1890, over a year later, by which time Louise was two months pregnant with their second child.

To Walpole’s dismay, Wiedemann was now representing herself, having not paid her solicitor. During the three-day hearing, Laura Walpole gave evidence for her son, saying that Wiedemann never mentioned any promise of marriage but had told her that she and Walpole were ‘intimate’. Other witnesses included a count, who produced evidence that years earlier, Wiedemann had told him, falsely, that she had borne his child and tried to extract money from him.

While some attested to her good character, it lost credibility amid evidence to the contrary. This included a letter she sent Walpole in November 1884, saying he must keep his promise to marry her ‘for the sake of our little boy’, even though she knew the child was dead. The doctor who had attended her told the court he was born at eight months and did not survive.10

After contradicting herself many times, Wiedemann was found to be an unreliable witness. In the libel claim, the judge directed the jury that if Walpole believed the words he said to Cooke about her to be true, she would not be entitled to damages. The main question, though, was whether Walpole had promised her marriage. As the jury adjourned to consider its verdict, he had reason to feel cautiously optimistic. But when the foreman returned, he said they were so divided that a verdict could not be reached. The case would not be heard again for another year.

While Valery Wiedemann hung around like a miasma, it cannot have made Louise’s acceptance by London society very easy, but friends stood by her. When Dolly was 6 months old, Louise stayed again at Inverlochy Castle and met the Danish artist Cathinca Amyot, who made a delightful pencil sketch of a little girl staring at her bespectacled nurse and asking her childish questions, as Dolly would do one day. She was too young yet to be aware of any family turmoil and spent much of her day in the care of her nurse.

As Walpole went between city and country, Louise’s London base became an elegant and spacious property at 15 Grosvenor Square, Mayfair, probably leased by Corbin, whose wife and younger daughter were also living there. They employed twelve servants, four of whom were French – Mrs Corbin was accustomed to employing them and they were very fashionable – and one African. Louise certainly needed some help because on 9 January 1891, aged 24, she gave birth to a son, Horatio Corbin Walpole. Now caution was thrown to the winds as his arrival was announced in several newspapers, with the words Walpole had been longing to write: the boy was ‘the proximate heir to the Earldom of Orford’.

Whatever he dreaded might be the outcome of Wiedemann’s case, his heart must have been lighter as the next hearing approached in June. His solicitor highlighted the inconsistencies in her evidence, while also acknowledging that the jury might not approve of some of Walpole’s past conduct. Nevertheless, he said, it must not find that a promise of marriage was given.

But it did and awarded Wiedemann £300 in damages. Although that was far less than she had claimed, the verdict implicitly confirmed Walpole as a cad. Now it was his turn to appeal, on the grounds that there was no corroborative evidence to support her claim of breach of promise.11 On 31 July 1891, all three court of appeal judges agreed and reversed the verdict in Walpole’s favour, with costs – not that he was likely to see any, but it was a small price to pay for exoneration.

The fact that it had taken three hearings and nearly three years to reach this point was widely considered unacceptable, especially for Wiedemann, still seen by some as the victim.12 But she had not finished yet. She threatened a claim against Laura Walpole for libel, then began giving classical recitals in London based on her experiences. Changing her approach, in 1892 she started selling pamphlets at the Liverpool Exchange berating the wrongs against her, before moving her spot to London and Royal Ascot. In a final shot, she sought permission to appeal the verdict against her as an impecunious litigant. She got no further.

Notwithstanding Wiedemann’s continued attention seeking, the verdict in Walpole’s favour had at least removed much of the strain and he and Louise could focus on enjoying their young children. However, such pleasure did not last for long. On 20 May 1893, at the age of 2 years and 4 months, Horatio died at Waborne Hall. Four days later, he was buried at Wickmere, the Walpole family church, with a large stone cross marking his little grave. In the church itself, in front of two luminous stained-glass windows of saints, a marble statue of a small boy with curly hair and angel’s wings commemorates him.

Now Louise’s daybook, a reminder of her carefree days of not so long ago, contained verses from ‘Resignation’ by the American poet Henry W. Longfellow, about the death of a child, the sex adapted for their son. Written on black-bordered writing paper, three of the copied verses read:

He is not dead – the child of our affection –

But gone unto that school

Where he no longer needs our poor protection

And Christ himself doth rule.

Not as a child shall we again behold him

For when with raptures wild

In our embraces we again enfold him

He will not be a child.

But a fair youth in his Father’s mansion

Clothed with celestial grace

And beautiful with all the soul’s expansion

Shall we behold his face.13

It was written from 36 Bruton Street in Berkeley Square, the house Corbin had bought for her; undoubtedly anxious about all that had happened since his daughter’s marriage, it was a way of further ensuring her security. She was still young, 26, when Horatio died and had time to produce another son, as her husband dearly hoped.

Dolly was 4 when she lost her brother – old enough to be aware not only of a sense of loss but of the grief of those around her. As if by osmosis, she began to absorb ‘the ignominy of being “only a girl”, that horrid phrase that haunted my extreme youth’.14

Female she may have been, but Dolly’s education was not ignored, partly to endow her with the sort of skills and accomplishments expected of a girl of her background, with a view to making her desirable as a wife, and partly because of the Walpoles’ intellectual heritage, whose legacy was in evidence among recent women. Dolly’s great-aunt, Lady Dorothy Nevill, and her late sister, Rachel, despite the otherwise old-fashioned views of their father, had received from carefully chosen tutors an unusually wide education, which included being taught to read and write in Italian, Greek, French and Latin and was augmented with extensive travels in Europe.

Now, at the age of 67 and widowed for fifteen years, Dorothy Nevill was about to bring out a book on the history of the Walpoles and Mannington. It was bound to garner interest, for once the scandal of her early days was behind her, she had become a well-known figure in Victorian society, respected as much for her botanical knowledge (which won her the friendship of Charles Darwin) as her skills as a society hostess and confidante, especially to Benjamin Disraeli. Her views were still sought on a diversity of subjects, sometimes as ordinary as face soap, and she made no concessions to age, becoming endearingly eccentric in dress and demeanour. Circumstances would soon bring this clever, charismatic woman and her great-niece together. For now, though, the ‘small and not particularly attractive’ Dolly, who was ‘rather lonely, rather shy and apologetic’,15 had dreams and invented games and began to read voraciously.

On 7 December 1894, Dolly’s great uncle, the 4th Earl of Orford, died suddenly at his London house in Cavendish Square at the age of 82. It is unlikely she ever met him, for this cultivated, witty but eccentric nobleman, an old friend of Disraeli, had largely been a recluse for the past twenty-five years and separated from his wife for nearly forty, with their married daughters living abroad. As he left no legitimate male heir, his nephew Robert succeeded to the earldom and 5-year-old Dolly was elevated from ‘miss’ to ‘lady’. Although the press extolled the deceased earl’s intellect, it also raised his scandalous past, musing on how his career might have gone had it not been for his unhappy marriage and his eloping with the Countess of Lincoln. It was the same for Robert Walpole. He might now be the 5th Earl, but it would not be long before at least one newspaper slyly reminded its readers that he was perhaps best known for his court battle with Miss Wiedemann.

Dolly’s life would change beyond her title, because her father inherited two Norfolk properties: Mannington, where the late earl was buried in a tomb he had erected within a ruined chapel in the grounds, and Wolterton, which he had abandoned years earlier in favour of Mannington. With these houses came chilling stories that must have thrilled young Dolly. The earl had had a premonition of his death, when he heard that a ghostly figure long associated with the Walpole family at Wolterton had been seen again: the White Lady, who was said to appear whenever calamity was about to befall them. One theory was that she was from the Scamler family, who formerly owned the estate, whose grave in Wolterton Park had been dug up by an earlier Walpole and caused her eternal unrest. Such was the fear of this apparition that the family devised the custom, whenever there was a death, of driving the hearse three times around the now-ruined church to atone for the act of sacrilege.

However, the late earl’s sister, Lady Dorothy Nevill, who was raised at Wolterton, said she found no evidence of such an act and concluded that there was some other reason for her presence. Whatever the cause of this unhappy lady’s state, a sighting always caused anxiety. Dorothy recorded that shortly before her brother died, he told her about the figure, saying ominously, ‘It is you or I this time, for we are the only ones left.’16

As well as ghosts and graves, Robert Walpole – or to use the name by which he now signed himself, Orford – also inherited the contents of the houses, which included his uncle’s magnificent library of rare books. The rest of the earl’s estate was divided mostly between his illegitimate son and his sister, Dorothy: the only visitors he would receive in his seclusion.

As Wolterton was suffering from his neglect, its restoration was a long and expensive undertaking, and Dolly’s parents made Mannington their main residence. A year after they moved in, Augustus Jessop, a clergyman and writer friend of Dorothy Nevill, told her:

I don’t hear much of Lord Orford and her ladyship. A friend of mine was at Mannington the other day and was greatly charmed with the daughter – her little ladyship (by way, Lady Dorothy the second) wrote the man a pretty little letter and he is so proud of it that I think he is going to frame it and hang it up in his private sanctum.17

At 6 years old, Dolly was already making an impression.

Like Wolterton, Mannington had much to feed the imagination of a bright and curious child. During Dr Jessop’s own stay there in 1879, something happened that would fascinate firstly Norfolk and then the world. His vivid encounter in the library with a man thought to be Henry Walpole, a Jesuit who was executed in the sixteenth century, was a terrifying experience that he documented in great detail and remains a source of intrigue well over a century later.18

Smaller but older than Wolterton, the moated, medieval Mannington was beautiful and intriguing. Dolly loved playing in the grounds with its sacred groves, landscaped walks, sunken avenue of oaks, strange sepulchres and ivy-clad ruins. That which was not beautiful was curious. Above the entrance door was an eccentric reminder of the cynical nature of her late great-uncle in the form of an unpleasant testimonial to his wife and to his mistress, Lady Lincoln:

What is worse than a tigress? A demon.

What is worse than a demon? A woman.

What is worse than a woman? Nothing.

Dolly could ask her great-aunt more about the house, for her book on Mannington and the Walpoles was now published. The pair probably met for the first time when Lady Dorothy visited the new Earl and Countess of Orford shortly after her brother’s death. As she told her friend Lady Airlie:

I had such a dear visit at my nephew’s, such a delightful place with a moat of running water where Dorothy the 2nd fishes for our breakfast, and then of a night my nephew Robin [Orford’s pet name] and I pored over all the books containing the sayings and doings of our ancestors – and then one day we went over to see lovely Blickling [another Norfolk estate] and its charming hostess – another day to a far-off estate that Robin has.19

Louise often invited her to dinner, showcasing her excellent French and knowledge of its cuisine in her handwritten menu cards. As Dolly grew older, she was sometimes invited to join them. Her great-aunt’s attitude to life was one that would surely come to interest her. Dorothy Nevill disliked the fact that being a woman had stopped her from being accepted in a man’s world and resented being told that to attend the all-male gatherings of her brilliant surgeon friend, the polymath Sir Henry Thompson, she would have to wear trousers. When Lord Lytton, on first meeting her, said, ‘You are your brother in petticoats’,20 she took it as the highest compliment, holding the view that most women were stupid. Dolly no doubt sympathised with her frustration, but as she was born over half a century later, her stance would differ; while society was still patriarchal, women were (gradually) making inroads in areas dominated by men and Dolly would both celebrate and be an exemplar of the strengths of her sex.

Her own mother was an example of what a woman could do in the male-dominated world of sport. In 1895, Louise secured a place in the fishing annals as the only woman angler who had succeeded in catching two tarpon in one day when she, Orford and Dolly were holidaying in southern Florida the previous Christmas. One of the fish she caught weighed 128lb and although her husband caught a bigger specimen, he only managed the one.

For Dolly, that holiday also stood out because of her first sighting of an alligator. While her parents fished, she took advantage of her nurse’s lapse of attention and wandered off along the riverbank. She stumbled across a party of men who had just landed what she saw as ‘the dragon of all my fairy tales […] the ugly Apocryphal beast’, whereupon she announced with all the grandiloquence of a 5-year-old, ‘When I am big I shall kill those’,21 causing much laughter from the men whose prototypes would be her hunting companions one day. After all, she was only a girl.

2

A DIFFERENT DRUMMER

As they settled into Mannington, Wolterton was by no means forgotten because, as owner of the estate that covered seven parishes, Orford had wide responsibilities with which Louise assisted him. As lady of the manor, her participation in the community and support of charitable causes was expected and seems to have been generously given. In June 1897 alone, the earl and countess entertained 300 local schoolchildren at a tea party at Wolterton and he hosted dinner at a local hotel for all the male estate workers.

Dolly was also expected to get involved. At Christmas, she helped Louise with the annual distribution of flannel and calico to their cottage tenants, of which there were over 100. The amount of material each cottager received was calculated on how many children they had; if none, they received 3s instead. Each tenant also received a gift of coal from the earl.

For the time being, Wolterton’s great house remained a faded glory which fascinated visitors, including Louise’s sister, Mary, and her husband, Kirkland Cutter, a noted Spokane architect favoured by their father, who would replicate some of its features back in the USA.1 Dolly’s position as the only child remained, for her parents’ wish for another had not been fulfilled. ‘My little world became resigned to the fact that in due course I should have the succession of things,’ she wrote. ‘It was a goodly heritage, but of that I realised little at the time.’ Without companions of her own age, she invented games which she played among the gardens and woodlands of Mannington and Wolterton and had dreams of ‘pirates and savages, of desert islands and hairbreadth escapes’. They were, she concluded, ‘premonitory dreams and games […] unlike those of most little girls’, and it was around this time that she began to hear ‘the different drummer calling, one that sets a different beat to some of us […] to do or be things that are accounted eccentric by more normal folk’.2

Her dreams often started in the same way. ‘If I had a million pounds,’ she would muse, she would conquer the world, climbing the Poles, exploring the solar system and passing ‘the portals of eternity’. She made huts out of old packing cases, ‘to the detriment of the shrubbery and the resentment of the gardeners’, and hid in them any of her pocket money that had not been deducted for misbehaviour. From sticks and stones and bits of string she fashioned an armoury with which, crawling through the bushes and flower beds on all fours, she fought battles ‘from the Crusades and the Armada to light skirmishing with howling cannibals’.

Although her parents sometimes took her travelling, they also spent time away on their own at favoured spots like the South of France, where friends kept a yacht and took them sailing in the Mediterranean. Like most upper-class children of the era, Dolly saw her parents for a limited time each day and was left in the care of servants. She made the most of it: ‘While my governess placidly did her knitting and read love letters from her fiancé, a battered boat on the lake was my raking felucca,3 with a skull and crossbones laboriously traced with ink on my pocket handkerchief.’

Without the distraction of siblings or other playmates, Dolly found magic in her surroundings. ‘The park and gardens were haunted for me by goblins and djins; the donkey that drew my cart was an enchanted princess’, all of which would influence her writing. Her story The Call,4 which would be published in 1914, begins:

In the windswept garden, through the tormented February weather, the little white lady walked alone; such a very little lady, so young and slender and fragile – and always alone. She scarcely knew if she regretted it. She had known so little companionship; harsh, unfriendly parents, and now a still more harsh and unfriendly husband; for she was married, though she could hardly tell you herself how it had come about.

The lonely lady loves:

… the old neglected garden […] with its maze of dusty tangled paths, its little dells of a damp, brilliant green and strange half-hidden moss-grown statues. And here her young soul grew. She had felt the mystery of every secret place; she had weaved a legend around every old stone image.

In the centre of a grassy spot, enshrined in laurels, she finds a statue of Pan whose artist had ‘breathed into it some bizarre spirit of pagan days’, and she is entranced by the ‘virile slim lines of the body’ and how the ‘supple fingers’ hold the pipe so lightly:

It was here, on days when the sun shone that the little lady used to come and lie in the tangled grass and meditate on life, quaint, unusual meditations, nurtured on solitude and dreams.

The lady’s dreams turn to erotic musings and, in her lonely state, Pan becomes her lover whom she visits at night, tiptoeing through the moonlit garden to rest her smooth cheek on the cold stone of his body. It cannot end well.

But for now, Dolly’s thoughts were those of an innocent child excited by the books she read voraciously, most of which involved travel. Swiss Family Robinson was a favourite: a story of a family of immigrants who are shipwrecked en route to Australia; and Arabian Nights, the collection of ancient folk tales from the Middle East and Asia. She was absorbed by Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island from which, to the despair of her governess, came her ‘battle cry’, ‘Yo, ho, ho and a bottle of rum!’ Added to these came fascinating tales of countries her parents had visited after their marriage – Japan, Ceylon (now known as Sri Lanka), the West Indies.

In March 1898 her parents sailed away on another extensive trip, which was to include British Columbia as well as their first visit to the USA since they succeeded to their titles. As Louise was now a countess, the American press were eager to report her proposed visit to her home country: Corbin’s main base was Spokane in Washington State, but he also had many business interests in New York.

Later that year, with her 24-year-old governess Kate Craven, Dolly joined her parents when they visited her Uncle Austin Corbin’s 30,000-acre ranch in New Hampshire with its huge herd of buffalo, and they all spent the Christmas holidays in New York. She would remember her first sea journey as ‘a very small and miserably seasick child, crossing the Atlantic to North America, in the teeth of an icy northerly gale’,5 although, fortunately, it did not put her off sea travel forever. She was becoming very fond of the USA, not just for its vast wildness but its human stories, of hold-ups and the pony post and the brave ‘Forty-Niners’, the thousands of hopefuls from all over the world who in 1849 made the long and often perilous journey to California to find their fortune in gold.