Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

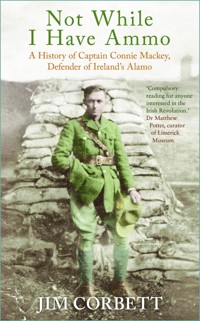

'Compulsory reading for anyone interested in the Irish Revolution.' – Dr Matthew Potter, curator of Limerick Museum During the Irish Civil War, between the 15 and 20 July 1922, the Republican-held Strand Barracks in Limerick, on what is now Clancy's Strand, came under constant ferocious attacks from Free State troops. They attacked the barracks repeatedly with armoured cars, and a non-stop bombardment of sniper, machine gun and mortar fire. All attempts to capture the barracks were resisted fiercely by the brave men inside. Finally, when everything else failed to dislodge these gallant men, the Free State turned an 18-pounder Artillery Gun on the barracks. This was the only time a siege gun was used in Limerick since the siege of 1691. The officer in charge was told to surrender the barracks or be held responsible for the loss of life. His response was "he would not surrender while he still had ammunition". This man was Captain Cornelius McNamara of 'A' Company, 2nd Battalion, Mid-Limerick Brigade, but was known to his men as Connie Mackey. An intimate friend of the former Irish president Sean T. O'Kelly, Connie was part of a golden generation of unselfish Irishmen with high ideals who were prepared to risk and endure everything for the sake of their country and countrymen. This is his story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 231

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to the memory ofmy grandfather, Connie McNamara, and alsoto my mother, Patsy Corbett.

First published 2008

This edition first published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Jim Corbett, 2008, 2025

The right of Jim Corbett to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 909 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Preface

List of Abbreviations

His Early Life

1916: The Easter Rising

1917: The Second Battalion and the IRB

1918: Promotion and the Conscription Crisis

1919: The War of Independence and Robert Byrne

1920: The Court Martial and the ASU

1921: Internment and the Truce

1922: The Civil War

Ireland’s Alamo

Imprisonment and the End of the War

Marriage and Exile

Remarriage and Clenor

Funeral and Firing Party

Bibliography

Endnotes

Captain Connie Mackey

6 April 1896 – 15 December 1957

‘A’ Company, Second Battalion,

Mid-Limerick Brigade,

Irish Volunteers 1916 – 1923

Foreword

When Connie ‘Mackey’ McNamara died in 1957 he left behind a legacy which was in great danger of being consigned to the realms of the forgotten. He was not a man who extolled his own virtues, and so what Connie had achieved was in great danger of being lost. Fortunately for his descendants, and indeed for all who have an interest in the past, his grandson Jim Corbett took on the research of Connie McNamara, his times and his adventures. Jim never met his grandfather, having been born long after Connie had died, but from the research he has carried out, he has, effectively, brought Connie back to life. His painstaking research has breathed new life into a man who was born at the end of the nineteenth century and lived through some of the most momentous times in Irish history.

Connie McNamara was born into a Limerick far removed from that of the vibrant city of the twenty-first century. It was an inward-looking place, whose industrial life was dominated by the activities of four big bacon factories; Shaw’s (which later became Clover Meats in 1950), Matterson’s, O’Mara’s and Denny’s, and the milk processing plant belonging to the Cleeve family. The owners of these big factories were largely members of a Protestant commercial class which had little in common with their largely Catholic workforce. When Connie McNamara joined the IRA in 1916 he was setting out on a treacherous road, and few could have predicted where it would lead. Unlike some of those who joined up, Connie McNamara was not simply going through the motions, and he soon began to rise through the ranks of the IRA. He took part in a number of actions in the War of Independence, the most notable of which being the rescue of Robert Byrne from the Union Hospital in April 1919. Unfortunately Byrne died as a result of wounds received from one of his RIC guards, Constable Spillane, making him the first Republican casualty of the war.

Following the signing of the Treaty in December 1921, Connie McNamara took the Anti-Treaty side. As the Civil War broke out in Limerick in July 1922, Connie was in charge of the garrison of the Strand Barracks. When the barracks was shelled by Free State artillery, Connie and his comrades resisted bravely, but eventually, when the barracks was in ruins, they were forced to surrender. He was complimented for his bravery and tenacity by the officer in charge of the attacking force. Following the surrender Connie was imprisoned along with a number of very important national figures.

His standing was such that when he applied for a pension in later years, among his referees was Michael Brennan, who was in charge of the Free State forces in the Limerick area. This is very significant, as, more than anything, it reflects Connie’s standing not just among his comrades and friends, but even among those who were later his enemies.

Tom Toomey, M.A.

Tom Toomey was a local Limerick historian who passed away on 27 April 2024. He co-authored An Antique and Storied Land: A History of the Parish of Donoughmore, Knockea, Roxborough and its Environs in County Limerick with H. Greensmyth in 1991. In 1995 he published Forgotten Dreams: The life and times of Major J.G. ‘Ged’ O’Dwyer. He also wrote numerous local history articles for various publications. In 2010 he published The War of Independence in Limerick 1912–1921.

Acknowledgements

In writing this history of Cornelius McNamara, there were a number of people who were incredibly generous, and I would like to thank them for their assistance and patience in dealing with my often difficult requests and never-ending enquiries in the search for nuggets of information relating to my grandfather, and the period covered. Without their support and encouragement, I would have been unable to compile this history and see my dream realised.

A very sincere and genuine thank you to the following: Roger Black and the staff of the Roger Black Gallery, who arranged to have the black and white picture of Connie in his Volunteer uniform painted; Commandants Liam Campbell and Victor Laing, of Military Archives, Cathal Brugha Barracks, who pointed me in the right direction and gave my research focus; Marie Treacy and Margret Kilcommins, of the Veterans Administration section, Department of Defence, in Renmore, Galway, who provided Connie’s pension details, which included a statement of his military service; Lar Joye, of the National Museum, Collins Barracks, Dublin, who allowed me to photograph Volunteer uniforms and translated the Gormanstown Choir names into English from Irish; Deirdre Griffin of Limerick City Registrars, St Camillus’ Hospital, Limerick, for the birth, marriage and death certificates of the McNamara, Moakley and Corbett families, which allowed me to build a family tree; Sharon Clancy, who kindly obtained a copy of Connie’s obituary; Des Long, of the Limerick Republican Graves Association, who provided me with IRA membership lists;Tom Toomey, for clarifying various Volunteer activities and allowing me to get into a Volunteer’s mindset; Phillip Turner, for drawing the map of the Strand Barracks; Mike Ratcliffe of Snappy Snaps, Croydon, for his advice in illustrating the book; James McMahon and Roger Boulter, for allowing me access to their research; Gearóid Moroney for setting up the website: www.conniemackey.com; John O’Shaughnessy, Tom O’Neill and Ruan O’Donnell for their sympathetic editing and proofreading – they made an unruly work look respectable.

And last but not least, thank you to the various members of the Corbett, McNamara and Moakley families, whose first-hand information and family records were invaluable, and the support of my friends Paul and Carole Mas, and to the many other people whose kind assistance helped me to produce this book. I apologise to anyone I have left out. Any errors or omissions are entirely my own, my sincerest thanks to you all.

About the Author

Jim Corbett was born and educated in Limerick City. He left Limerick after secondary school and moved to Croydon, England in 1988, where he still lives. He briefly studied business in London and has spent the past twelve years working in the telecommunications industry in London. While working for Vodafone, he wrote the Vodafone Music Club Weekly Magazine. He began writing in 2005 and is very much interested in twentieth-century Irish history.

Preface

I am Connie’s grandson. All through my life my mother told me stories about my grandfather Cornelius McNamara, a member of the Old IRA. We had his War of Independence Medal, an old black-and-white picture of Connie in his Volunteer uniform, and an old bullet from a battle that took place in the Strand Barracks, Limerick, during the Irish Civil War. Also in our possession was an autograph book, with some strange illustrations and poems from his time as a prisoner of war at Gormanstown Internment Camp, Co. Meath. My mother told me stories about her father; of fellow Volunteers he was interned with, of being forced to run over broken glass, and of having to sleep in graveyards when he was on the run from the British. But apart from that, we never knew the full background of our grandfather, who, as it transpired, had a fascinating story to tell.

I decided to find out as much as I could about this amazing man, whom I had never met. As I researched his contribution to Irish history, I had a growing desire to have his life documented for posterity. He was one of a golden generation of unselfish Irishmen with high ideals who were prepared to risk and endure everything for the sake of their country and countrymen. I wanted to give him the place in history that I felt he deserved, and to give back to the people of Limerick, the story of one of her most gallant sons. My research commenced in January 2006, and after many amazing twists and turns, delays and dead ends, I am now privileged to present the life and times of Cornelius McNamara. The information contained in this book was gleaned from many different sources in Ireland, Britain and the United States of America. So, allow me to present to you the story of this fascinating man.

List of Abbreviations

AAG

Assistant Adjutant General

ASU

Active Service Unit

Batt.

Battalion

Bde

Brigade

C-in-C

Commander in Chief

CO

Commanding Officer

COIR

Chief Organiser of the Irish Republic

Col.

Colonel

Comdt

Commandant (Irish equivalent of a British Army Major)

Comdt-Gen.

Commandant General

Coy.

Company

DAAG

Deputy Assistant Adjutant General

DI

District Inspector (RIC)

DJAG

Deputy Judge Advocate General

DORA

The Defence of the Realm Act

DRR

Defence of the Realm Regulation

FS

Free State

GAA

Gaelic Athletic Association

Gen.

General

GHQ

General Headquarters

HSE

Health Services Executive

I/O

Intelligence Officer

IRA

Irish Republican Army

IRB

Irish Republican Brotherhood

IRPDF

Irish Republican Prisoners’ Dependents’ Fund

JAG

Judge Advocate General

Lt

Lieutenant (British)

MPIF

Military Prison in the Field (Spike Island)

O/C

Officer Commanding

QM

Quartermaster

RAMC

Royal Army Medical Corps

RIC

Royal Irish Constabulary

ROIA

Restoration of Order in Ireland Act 1920

RUC

Royal Ulster Constabulary

Vol.

Volunteer

Map of Munster Pertaining to the Activities of Connie McNamara

Map of Limerick and surrounding counties. (Illustration by James McMahon)

Oil painting of Cornelius McNamara in Volunteer uniform c.1917, taken from a black and white print.

His Early Life

Cornelius McNamara, better known to his friends and fellow Volunteers as Connie Mackey, lived at 1 Blackboy Pike, off Mulgrave Street. He was described to me as a quiet and humble man, and, according to the 1925 passenger list of SS Celtic, he was 5ft 7in tall with blue eyes and brown hair. He entered this world on 6 April 1896, the only child of Michael McNamara, a pork butcher, and Mary (née Greot), of Blackboy Pike, and was named after his grandfather Cornelius McNamara. On 28 April 1900, when Connie was just four years old, his mother Mary died after a four-month battle with TB, in the City Home Hospital, Limerick. Three years later, his father Michael married Hanorah Minihan and they had seven children; Patrick, Tom, Mamie, Babe, Michael, Josie and Christopher.

Like so many of his contemporaries, Cornelius received his formative education in the Christian Brothers School, Sexton Street, Limerick, which, a century on, continues to be one of the leading learning establishments in the region. He started in primary school around the age of five in 1901, and then, when around twelve years old, he attended the secondary school, staying for a few years before leaving around the age of fourteen to become an apprentice butcher. On finishing his apprenticeship he became a butcher in one of the large bacon factories in Limerick, just like his father, probably working in Shaw’s on Mulgrave Street, which was just down the road from his house in Blackboy Pike. Cornelius was a keen hurler and a member of the Faughs GAA club, which drew its membership from the region around Ballysimon and Blackboy Pike.

Connie’s father and stepmother, Michael and Hanora McNamara.

Pádraig Pearse and Roger Casement came to Limerick in early 1914 to raise Volunteer companies. Connie did not join up straight away like so many others. As the eldest, he chose to remain at home to help and support his parents and family, although he was very much aware of how the Volunteer numbers in Limerick were increasing. The following year, in October 1915, Connie joined the Volunteer movement, but remained in his trade to finance his activities.

1916: The Easter Rising

In October 1915, aged nineteen, Connie enlisted in ‘C’ company Limerick City Battalion, under Commandant Michael Colivet, Captain Liam Ford, 1st Lieutenant Joseph McKeon and 2nd Lieutenant Arthur Johnson. Connie received his initial Volunteer training under Arthur Johnson, which consisted of route marches every Sunday and training sessions up to four nights weekly, including military instructions and rifle target practice. At this time Connie also took the opportunity to raid for arms whenever possible.1 Connie joined the Volunteers because Ireland, and of course Limerick, was under British rule at the time. The principal employers in Limerick were Protestant families, descendants of English settlers. The suffering of the Irish famine (1846–1849) would still have been in living memory for grandparents. The injustices handed out under a foreign occupation ignited a spark and a thirst for freedom. A Gaelic revival was underway, and people were starting to express their Irishness.

The Gaelic League was founded in 1893 in order to promote the Irish language. The Irish language was read and understood by a large percentage of the population; non-speakers and those with limited knowledge were encouraged to attend language classes. Michael Collins also went to Irish language classes, while a resident in London in 1909. The GAA was founded in Thurles on 1 November 1884, with the purpose of promoting the national games, hurling and Gaelic football, but with an emphasis on all aspects of Irish culture. The Volunteer movement, meanwhile, gave men of fighting spirit the avenue to liberate Ireland by the use of physical force. Connie was a keen hurler and the 1911 census records confirm he was a fluent Irish speaker at age 15, and he was the only Irish speaker in the household. The Irish scripted pages in Connie’s Gormanstown autograph book show he could read and write Irish as well.2

This book is a biography of Connie’s life, and it is set against the local and national events of those turbulent times. The Easter Rising, the War of Independence and the Civil War have been extensively documented. I have delved into the historical background to give relevance to Connie’s activities and actions while in the Limerick City Battalion, and also ‘A’ Company, Second Battalion, Mid-Limerick Brigade.

The Irish Volunteers were founded at the Rotunda meeting in Dublin on 25 November 1913. The first company to be formed outside Dublin was Athlone, and the second, in Dromcollogher, Co. Limerick. The early formation of the Dromcollogher Company was due to Fr Tom Wall, the parish curate. A meeting was held in the Athenaeum Hall in Cecil Street, Limerick on Sunday, 25 January 1914, to inaugurate a corps of Volunteers in the city. The Athenaeum then became the Royal Cinema in 1939 and now stands derelict.3 The meeting was addressed by Pádraig Pearse and Roger Casement and practically every man present enrolled. Offices were opened in No.1 Hartstonge Street and soon there were sufficient numbers to allow for the formation of eight companies. Connie was eighteen years old and fully aware of these goings-on, the early seeds of joining the Volunteer movement were planted in his mind. Mary Spring Rice, of Mount Trenchard near Foynes, helped to plan and finance the famous Howth gun-running expedition. She was aboard the yacht Asgard with her friends Erskine Childers and wife, when guns were landed at Howth, Co. Dublin, on 26 July 1914.4

The Limerick City Battalion numbered around 1,250 men. After the onset of the Great War, John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, voiced his belief that a measure of self-government would eventually be granted to Ireland. He also held the view that such an eventuality would stave off partition in the North.5 Redmond supported the British war effort; the result was that the Volunteer movement split in September 1914. In Limerick, over 1,000 men sided with Redmond, and became known as the National Volunteers.

A lifelong friend of Connie’s, Paddy O’Toole, enlisted in the Connaught Rangers in 1912. After the Great War, he returned to Limerick and became a quartermaster in ‘C’ Company, Limerick City Battalion. There are no further records of his Volunteer service. However, most of the 150 guns that were acquired before the split remained in the hands of the Volunteers who remained loyal to the original aims of the movement. William Lawlor was the only instructor that had not gone over to the Redmond camp, and it was feared that the lack of instructors would have a disastrous effect on the training programme. However, on 24 November 1914, Captain Robert Monteith of ‘A’ Company of the Dublin Brigade was banished from Dublin by the British authorities due to his Republican activities. He then came straight to Limerick, where he proved himself a valuable asset by assisting Ernest Blythe with the training of the Limerick Volunteers.6

Soon after the formation of the Volunteers in Limerick, a branch of Cumann na mBan, the women’s auxiliary unit of the Irish Volunteers, was started as well. The first meeting was held in the Gaelic League Rooms as the majority of those attending were members of the Gaelic League. Madge Daly was elected president, a position she held until 1924, except for 1921, when Mrs O’Callaghan, the wife of the murdered Mayor Michael O’Callaghan, took the position. Classes were started immediately in first aid, home nursing, drill, signalling and also instruction in the use of arms. Subscriptions were donated at meetings and functions; all monies raised went to the Volunteers’ arms fund. The Redmondite split of September 1914 had little or no effect on the Volunteer ladies in Limerick, however the Redmond faction did start the National Volunteer Ladies Association, which had their headquarters in O’Connell Street, but they soon faded away.7

On 15 February 1915, Padráig Pearse, director of military organisation for the Volunteers, was also on the IRB’s supreme council and its secret military council, the core group that began planning for a rising. He wrote to the Limerick City Battalion, ‘There are many who think that the Limerick City Battalion is the best we have. There are good men in command of it; men whose loyalty, courage and prudence are not surpassed in Ireland.’

The nucleus of the Volunteers in Limerick City comprised of three men, Commandant of the Limerick Brigade, Michael P. Colivet; Vice-Commandant, honorary Colonel James Leddin, and Adjutant George (Seoirse) Clancy. Three weeks before the Rising, Colivet, Connie’s commanding officer, was ordered by GHQ in Dublin to speed up his battalion and brigade organisation as events were now reaching a climax. He had eight battalions under his command but only the Limerick City Battalion, which Connie was attached to, was reasonably well armed. Furthermore, Colivet’s battalions were less than full strength, numbering no more than 200 men each, whereas a battalion should have comprised of at least 500 men. Connie’s battalion never mustered more than 205. At best, Colivet could count on no more than 1,600 men and these were far outnumbered by the better-armed British forces, whose strength was around 3,000 men in Limerick.8

In the autumn of 1915, Pearse outlined the general plan for the Rising to Austin Stack, a member of the IRB and commandant of the Kerry Brigade, and Alfred Cotton, also a member of the IRB and a captain in the Kerry Brigade. The plan was that the Cork Volunteers would move towards Macroom and link up with the Kerry Brigade, who in turn, would be in communication with Volunteers in Clare, Limerick and Galway. A line would eventually be held from the Shannon, through Limerick and East Kerry, to Macroom. The units of the Irish Volunteers in Ulster would then occupy positions from the Shannon to the south of Ulster. The Rising would begin with the Declaration of the Republic and the seizure of Dublin, with attacks against British troops in adjoining counties. Country Volunteer forces would move towards the capital to relieve the pressure on the Volunteers who had seized a ring of positions inside it.9

The arms and ammunition were to be landed at Fenit harbour in Tralee Bay, Co. Kerry, from the German arms ship Aud, and distributed to the Kerry, Cork, Galway and Limerick Volunteers. Stack and Cotton were to have a goods train ready to leave Fenit with the arms. Part of the armament was to be left at Tralee, for distribution to the Cork and Kerry Brigades and the remainder sent by goods train to Limerick, where arrangements would be made to dispatch them to the Galway area. At Fenit, a pilot would have to be on the alert for signals agreed upon with the arms ship, in order to meet it and guide it into the pier. A cable code was to be sent to the USA announcing the proclamation of the Republic. Everything, as far as the south and west were concerned, depended on the safe arrival of the Aud and the distribution of the arms to the waiting Volunteers.10

The Volunteer leaders originally asked that the Aud be in Tralee Bay between 20 and 23 April. After all the arrangements were in place, GHQ then made their fatal error. They decided that, ‘Arms must not be landed before night of Sunday, 23.’ They believed if the arms were landed earlier, the British would be alerted and strike at them before the arms were received.11 By the time this message reached Germany via America, the Aud was already on her way to Ireland, and she did not have wireless equipment. The plans for a nationwide insurrection were now doomed. The Volunteer leaders in Dublin knew nothing of this and would only learn of it when it was too late. They went ahead with their preparations for the Rising.12

Limerick was a key area in the insurrection plans. On Tuesday 18 April, Capt. Sean Fitzgibbon arrived in Limerick from Dublin headquarters with instructions for Colivet from Pearse. These new instructions clashed with the plan of operations, which the Limerick Brigade had worked out. According to Colivet’s new instructions, he was to receive the arms from Fenit in nearby Abbeyfeale, then take his requirements for his own area, and take the rest of the arms to Galway. Police and military positions in Limerick City were to be attacked to cover the transfer of the arms train safely across the Clare line at Limerick station. These new instructions were so different from his original instructions that Colivet decided to go to Dublin to have the matter clarified by Pearse himself.13

The next day, he met Pearse at the North Star Hotel, near Dublin’s Amiens Street Station. Pearse confirmed his instructions and told Colivet to cancel all previous plans and concentrate on the arms landing. Colivet asked Pearse point blank, ‘This means insurrection as soon as the arms are landed and we get them?’ Pearse replied, ‘Yes and you are to start at 7.00p.m. on Sunday. You are to proclaim the Republic and as soon as things are secure in your own district, move eastwards.’ Finally, Colivet was then told he would have to work out the local details himself. So, at less than a week’s notice, Colivet had to plan in detail the part Limerick was to play in the Easter Rising.14

As soon as Colivet arrived back in Limerick, he summoned his brigade staff to a meeting at the home of George (Seoirse) Clancy, in the North Strand. Michael O’Callaghan also lived on the North Strand, but on the opposite side of Sarsfield Bridge. Both were later to become mayors of Limerick and both were brutally murdered on 6 March 1921. Finally it was agreed that Connie’s Limerick City Battalion should march out of the city at 10.00a.m. Sunday, to Killonan, Co. Limerick, as if for the previously announced three-day manoeuvres. The return to the city was timed for 7.00p.m., when all police and military barracks in the city were to be attacked, after telegraphic and telephone wires had first been cut, as well as railway communications with Limerick Junction and Dublin. It was intended that the police and military garrisons were to be confined to their barracks by the attack, acting as a diversion until the Kerry arms train had passed safely into Clare. When the arms reached Limerick, the barrack attacks were to be followed through until the buildings were taken.15

As the train had to cross the Limerick lines to the south unnoticed and uninterrupted, the police and military diversion was essential. At Newcastle West on the following day, the Volunteers were to be posted to take over the train at Abbeyfeale, and to attack the police barracks in Newcastle West and see the train through safely. They were also to attack and disarm any police likely to interfere with the plans. The Volunteer unit at Newcastle West was to watch the station very closely, as it was a terminus where all trains had to be reversed, and the delay offered opportunities for police and military interference. GHQ issued an order that any armed clash with police and military must be avoided until 7.00p.m. on Sunday. The Limerick plan provided for all available Volunteers to be armed and taken aboard the train as it proceeded towards Limerick. In Co. Clare, Captain Michael Brennan and the Mid-Clare and East Clare Volunteers were to seize Ennis and all stations to Crusheen, and finally, after disarming the RIC in various localities, take up positions north of the Shannon at Limerick, complete its encirclement, and force a surrender of hostile forces within.

In summary, the Cork, Clare, Tipperary and West Limerick Volunteers were to seize railways and barracks in their immediate areas, disarm the police, surround Limerick and march to relieve Connie and the City Battalion. The plan assumed that the barracks would be taken without a hitch, that the police would be overcome, that the arms train would pass without interference, and most of all, the arms would be safely landed from the Aud.16