8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

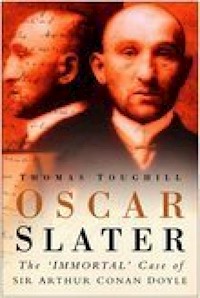

In 1909, Oscar Slater, a German Jew, was convicted and sentenced to death for the brutal murder of Marion Gilchrist, an elderly Glasweigan spinster. His trial is known to have been one of the most scandalous miscarriages of justice in the annals of legal history. This book is provides an account of this infamous case.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

OSCAR

SLATER

O, what a tangled web we weave,

When first we practise to deceive!

Sir Walter Scott, writer and advocate

OSCAR SLATER

The ‘IMMORTAL’ Case of

SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

THOMAS TOUGHILL

First published in 1993

This new revised edition first published in 2006

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2012

All rights reserved

© Thomas Toughill, 2006, 2012

The right of Thomas Toughill, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 8268 2

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 8267 5

Original typesetting by The History Press

This book is dedicated to Detective Lieutenant John Thomson Trench, a man of whom any society should be proud, and to an anonymous lady who obeyed God’s commands

Contents

Acknowledgements to the new edition

Acknowledgements

1 Introduction

2 A Suspect

3 A Murder

4 An Investigation

5 An Extradition

6 An Identification Parade

7 A Trial

8 A Reprieve

9 A Secret Inquiry

10 A Release

11 An Appeal

12 A Conclusion

Bibliography

Acknowledgements to the new edition

I would like to thank the following who helped me in the writing of this new edition.

I owe a special debt of gratitude to Joseph Craig, a retired Police Inspector of the Strathclyde Police and now a leading member of the Glasgow Police Heritage Society. Joe’s advice and enthusiasm proved immensely helpful to me in the writing of this book.

I also wish to thank Lyn Morgan of the Glasgow City Archives and Special Collections in the Mitchell Library, Glasgow for granting permission to quote from the private papers of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle; Lesley Richmond, the Duty Archivist at Glasgow University for permission to quote from the Police Files on the Oscar Slater case (GUA FM/2B/5/3); the staff of the National Archives of Scotland, in particular for their guidance in the reproduction of Crown Copyright material; Cilla Jackson, Special Collections Department, St Andrews University; Alan Grant, Information Services, University of Dundee; and Michael Bolik, Assistant Archivist, University of Dundee.

Acknowledgements

I would like here to express my sincere thanks to all those who helped me write this book.

I owe a special debt of gratitude to the staff of the Mitchell Library, in particular those dedicated souls in the Glasgow Room. I owe a similar debt to Mrs Anna Frackiewiz MA of Ancestry Research (Scotland).

I am grateful to William Hodge & Company Ltd for their kind permission to quote from the works of William Roughhead.

I would also like to thank Dave Mobbs and Jack Quar TD, LLB for reading the manuscript and commenting upon it. For help of a more technical nature, I am deeply grateful to Bill Rothwell and to my lifelong friend Norrie Macleod.

My thanks go too to Robin Odell for his encouragement. I can only hope that the contents of this book will persuade Robin to amend a future edition of The Murderers’ Who’s Who, that indispensable work of reference which he compiled together with the late Joe Gaute.

I acknowledge the help I received from Jack House, the author of Square Mile of Murder, and I regret that he did not live to read this book.

I am also deeply grateful to the following: the staff of the Scottish Record Office, especially those attached to the West Search Room; Mrs P. Russell of the Search Department of the Public Record Office; Peter Simkins of the Imperial War Museum; Robert Smart, Keeper of the Muniments, University of St Andrews; Michael Moss, University Archivist, Glasgow University and his assistant, Mrs Lesley Richmond; Kenneth Smith, University Archivist, the University of Sydney, Australia; Miss J. Coburn, Head Archivist, Greater London Record Office and History Library; Allyson Swny, Manuscripts Section, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich; F. J. Dawson, Departmental Record Officer, Ministry of Defence; Major (Retd) W. Shaw MBE, Assistant Regimental Secretary, Royal Highland Fusiliers; Bobby Burnet of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews; J.N. Hopkins of the General Register and Record Office of Shipping and Seamen; Katherine Milburn, Reference Assistant, The Hocken Library, University of Otago, New Zealand; and Fiona Oliver, National Archives, Wellington, New Zealand.

I cannot express in words the debt I owe my wife and family for putting up with me while I wrote this book.

It remains only for me to say that the views expressed in this book are mine and mine alone.

Thomas Toughill

1

Introduction

On 9th March 1950, Timothy John Evans, a twenty-four-year-old van driver of sub-normal intelligence, was executed for the murder of his baby daughter. At his trial, Evans had accused his landlord, John Reginald Halliday Christie, of killing his daughter and his wife. Christie denied the charge and was not doubted. Three years later, he was revealed to be a mass murderer and a necrophile, and was himself sentenced to death. British justice had hanged an innocent man.

On 6th May 1909, Oscar Slater, a German Jew living in Scotland, was convicted of murdering an elderly spinster, Marion Gilchrist, in her Glasgow flat, in December 1908. However, within hours of the gallows, and without proper public explanation, he was reprieved, and sent to do hard labour in Peterhead Prison. Following intense public pressure, he was released in 1927. The next year, a special Court of Appeal quashed his conviction on a point of law. He remained in Scotland and died there in 1948.

The former case is clearly the more tragic of the two. Evans was hanged, whereas Slater was not. And yet, the German’s case is in some respects the more disturbing of the two. Evans’ conviction was at least understandable, if not excusable. The evidence against him was, at first glance, strong. Moreover, he did confess to the crime, although he later retracted this statement. Given the circumstances of the case and the heinous nature of it, the police can be accused of nothing more than being over-zealous and incompetent. They rushed to secure the conviction of a man who appeared guilty, when they should instead have pondered long over the evidence and the mental condition of their suspect. Such a course of action would without doubt have led them to Christie.

There is little that is immediately understandable in the Slater case other than the obvious fact that Slater had nothing to do with the crime of which he was convicted. He was pursued to America by the Glasgow authorities on what they admitted was a false clue, brought back to Glasgow where he was put through a farcical identification parade, and then sentenced to death on evidence which was, to put it mildly, less than satisfactory. How, then, can the actions of the Glasgow Police and its guiding body, the office of the Procurator Fiscal, be explained? Can their handling of Slater’s case be ascribed to incompetence or natural eagerness to see the guilty party get his just desserts? Or was there something far more sinister afoot here?

Slater, for his part, claimed that he had been framed and called himself the ‘Scottish Dreyfus’, a reference to Alfred Dreyfus, the French soldier of Jewish descent who in 1894 was convicted on suspect evidence of being a German spy and sent to Devil’s Island. The Dreyfus Affair divided French society, with many people – including Georges Clemenceau, the future Prime Minister – claiming that the anti-semitic French establishment was actually protecting the real spy, one Major Ferdinand Esterhazy. Dreyfus was finally released in 1906 and restored to his army rank. After the First World War, the German government confirmed that Esterhazy had been the guilty party.

There is no doubt that anti-semitism did play some role in Slater’s persecution. It is worth noting that the Jewish community in Glasgow, about 8,000 strong at the time, kept a low profile during the case. For example, when Slater’s friend, Rabbi Phillips, organized a petition calling for Slater’s death to be commuted, the Jewish community in Glasgow made it clear that Phillips was acting in a personal capacity, and not a minister of their synagogue. Slater of course was unfortunate in other respects. He was not only a Jew; he was a German Jew in Scotland at a time when the British public had come to accept war with Imperial Germany as both imminent and inevitable. In addition, and perhaps most importantly, he was a disreputable German Jew whose lifestyle was genuinely offensive to the morals of the Presbyterian Scotland in which he was living. If Slater, whatever his race or religion, had been a married man fending for his wife and family, then the attitude of the Scottish public and certain officials involved in the case might have been very different.

There is another aspect in which Slater resembled Alfred Dreyfus. Like the Frenchman, he was championed by a great literary figure. Dreyfus had Emile Zola, the novelist, whose blistering open letter, ‘J’Accuse’, in the L’Aurore newspaper proved a turning point in the case. Slater, for his part, had Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, as his tireless champion. Sir Arthur eventually succeeded in freeing Slater, but such was the bureaucratic opposition the great man encountered that he once wrote in The Spectator magazine:

The whole case will, in my opinion, remain immortal in the classics of crime as the supreme example of official incompetence and obstinacy.

This book is an updated reconstruction of Sir Arthur’s ‘immortal’ case, based on the author’s 1993 publication, Oscar Slater: The Mystery Solved. Such a task has been made possible, indeed necessary, through the release since that year of all known Government and Police files on the case as well as the recent purchase by Glasgow City Council of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s correspondence on the affair, which papers are now to be found in Glasgow’s Mitchell Library.

What follows is therefore very much a new edition of the author’s earlier work, indeed almost a new book. With access to the above material, the author has been able to produce a more detailed study of this truly scandalous case, using evidence which puts his findings beyond dispute. The important anonymous letters, which featured in the first edition and which identify the real killer, are naturally mentioned here. Included though now for the first time are Police records which show, amongst many other things, how the murderer lied in order to establish a false alibi. The attempt by Detective John Trench to uncover the sordid truth which lay behind Slater’s conviction is studied here, as it was in the first edition. What is also studied here however is the posthumous role which Trench played, via a secret police document, in convincing Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald to intervene decisively in this case and free Slater. The conspiracy by Crown officials to protect the well placed men involved in Miss Gilchrist’s murder, which was outlined in the first edition, is now elaborated upon. After reading Trench’s secret document which had been passed to him in confidence by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Ramsay MacDonald concluded that those Crown officials secured Slater’s conviction by ‘influencing witnesses and with-holding evidence’. With the help of the above records, the author is now in a better position to describe how that perversion of justice was carried out.

The author wishes to stress that it is not his aim to denigrate or insult the British system of justice. After all, the 20th Century was a period of mass slaughter in which several ‘rulers’ around the world killed so many people that the numbers involved can not be counted, merely assessed. The very fact that we can still discuss with great accuracy the fate of one man almost 100 years ago shows that the British system does have something special. This case was surely an aberration, one in which the officials directing it were able to abuse the system and the trust placed in them.

Nevertheless, there are clear lessons to be learned from Slater’s fate. The more we understand about miscarriages of justice the better. As Timothy Evan tragically reminds us, these miscarriages still happen, which means they still wreck the lives of innocent people and allow the guilty parties to remain at large and unpunished. That alone is reason enough to acknowledge the relevance today of this, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s ‘immortal’ case.

2

A Suspect

Glasgow in Gaelic means ‘the dear green place’. This had indeed once been an entirely appropriate name. In the early 1700s, the writer, Daniel Defoe, visited Glasgow, then a thriving university and commercial community nestling on the banks of the banks of the river Clyde, and pronounced it one of the most beautiful small towns in the whole of Britain. However, if Defoe had returned to Glasgow in the early years of the twentieth century, he doubtless would have had a different opinion, for by then the Celtic phrase would have become an appellation of irony. What Defoe would have found was a smoky, grimy, slum-ridden economic colossus, a conurbation which had grown into one of the largest in Europe and a city which, within the British Empire, conceded priority only to one other.

It is no exaggeration to say that the industrial revolution started in Glasgow. It was during a lunchtime stroll through Glasgow Green, the oldest public park in Britain, that James Watt, the instrument-maker at Glasgow University, worked out in his mind the prototype of his steam engine. A contemporary of Watt at Glasgow University was Adam Smith, Professor of Logic and Moral Philosophy, who, in one of the most influential books ever written, argued that with little more than ‘peace, easy taxes, and tolerable administration of justice’ nations could not help but be wealthy. These two developments, the harnessing in facile form of one of the primal forces of nature and the creation of an economic system so attractive to the human spirit, changed the world for ever.

The effect of the Industrial Revolution in Glasgow was swift and dramatic. The city grew rapidly, street by street, block by block, factory by factory. People poured into the city from the countryside and later from Ireland, creating social and hygiene problems which no authority had ever encountered before and on an immense scale. The result was that large areas of the city deteriorated into hovels and slums where disease, poverty, and alcoholism became commonplace. But there was work to be had and money to be made. People therefore kept coming, supporting in one form or the other the heavy industry which was the mainstay of the local economy. From the Glasgow area came steel and locomotives to gird the empire together. Above all there were ships. Of all the shipyards in the British Isles, it was Glasgow’s Clydeside which played the major role in supplying Britannia with the vessels she required to supply and protect her empire.

The coal, smoke, furnaces and waste involved in the running of this voracious industry all combined to make the city dark and dismal, an appearance strengthened by the characteristic grey dampness of the local climate. Life in such a place was hard and unhealthy, at times downright dangerous given the level of violence in certain areas. To control and govern such a city required strict order and discipline. Here the authorities drew heavily on the ingrained conservatism of the Scots, especially their stoical acceptance of what fate throws at them, and the power of a no-nonsense Calvinist religion which offered little comfort to sinners this side of their interview with St Peter. Obey the law, follow the rules of society, and you will be looked after. Step out of line and you can expect no mercy. It was by these strictures that Glasgow, the ‘No Mean City’ was run.

There was of course another side to Glasgow. There was the fine Victorian architecture, such as the stunningly opulent City Chambers and, in areas far from the smoke and grime, splendid mansions and villas lined the broad, tree studded avenues. There were great rolling parks maintained for the enjoyment of all, rich and poor alike, and the magnificent, unspoilt Scottish countryside which surrounded the city. And there were the people, hard-working, puritanical, traditional and direct, but nevertheless friendly and fair minded as one would expect from a society which prided itself on its egalitarianism and its faith in the power of education. By European standards, this was an upwardly-mobile community willing to reward skill and enterprise. It was not though a cosmopolitan community. Despite its wealth and importance, Edwardian Glasgow was a parochial place, resistant to change, and deeply suspicious of anything foreign. It is in this context that the arrival in Glasgow in late 1908 of Oscar Slater, a German Jew, must be seen.

Oscar Slater was born Oscar Joseph Leschziner on 8th January 1872 in the town of Oppeln, then part of eastern Germany. His father was a Jewish baker, but Oscar decided that he did not want to go into the family business. At the age of fifteen, he became an apprentice to a local timber merchant. Despite his relatively poor schooling, he displayed a good head for business and later moved to Hamburg where he secured a job as a bank clerk. When conscription loomed, he did what many young men have done over the years; he moved abroad. Slater chose Great Britain as his immediate destination and for a number of years he travelled around that country – London, of course, but also Edinburgh and Glasgow. He also travelled to the Continent and to America. Having had little professional training, Slater was forced to rely upon his wits. He worked first as a bookmaker’s clerk, then as a bookmaker and finally as a manager of gaming clubs. He also dealt on occasion in jewellery. In addition, he consorted with, and possibly lived off, prostitutes. Given this lifestyle, it is not surprising that Slater resorted to the use of aliases. His own name he discarded on the grounds that it was unpronounceable by native English speakers.

During a lengthy stay in Glasgow in 1901, when the ‘Second City’ of the British Empire was celebrating its famous International Exhibition, Slater married a local girl. The marriage was a disaster. The woman was both a spendthrift and an alcoholic. Leaving her behind, Slater moved to London, where at the Empire Theatre he met a young Frenchwoman, Andrée Junio Antoine, whose professional name – and she did have a profession – was Madame Junio. They went to live in Brussels but Slater’s wife traced him there and began to bother him. Slater accepted the offer of a job in New York and, travelling under the names of Mr. and Mrs. George, he and his companion sailed for America. Slater had been in New York before, in charge of the Italian-American Gun Club in Sixth Avenue. Putting his experience to good use, he now spent a year running a club in Manhattan with a friend called John Devoto. However Antoine’s health broke down and by the summer of 1908, she and Slater were back in London.

Perhaps it was because business had been booming during his earlier visit to Glasgow that Slater decided to return there. In any event, he arrived in Glasgow on 29th October, staying for a few days at the prestigious Central Hotel. A week later he was joined by Antoine and her German maid, Catherine Schmalz. They lived for a while in lodgings at 136 Renfrew Street before moving in November to a flat at 69 St George’s Road, St George’s Mansions, a handsome sandstone building not far from Sauchiehall Street, one of the main thoroughfares of the city. Under the name “A. Anderson, Dentist”, Slater signed an eighteen-month lease on the property. Using the same name, he opened a Post Office Savings Bank Account and purchased some consols. From the shop on the ground floor of his building, he furnished his flat, to the value of £170, on hire-purchase. Around the same time, he made, in a nearby Charing Cross shop, what he doubtless then considered a much more trivial acquisition. This was a card, costing half a crown, which held together a set of household tools. The most prominent tool was a small hammer, weighing half a pound. The maid took to breaking the coal with it.

To Scots, Slater stood out through his appearance and accent as an obvious foreigner. Mary Cooper, who handled his laundry, and his barber, Frederick Nichols, both took him for a German. Cooper remembered him as having an abrupt and dominant manner. Physically, he presented a square, robust figure. Although only about 5 feet 8 inches tall, he was broad-shouldered and deep-chested to the extent that he found it necessary to have his shirts hand-made. Facially, his most prominent feature was his great Roman nose, which, as the result of a fist fight in Edinburgh, looked in full face twisted or broken. He was a man who took great pride in his appearance and was always well dressed, usually in dark clothes and a bowler hat. He visited his barber several times a week. He usually sported a moustache, but about fortnight before Christmas he had it removed. He decided almost immediately though to re-grow it and by later December his upper lip, according to his barber, was displaying a noticeable short moustache.

In Glasgow, Slater’s life revolved around public houses, billiard rooms and gambling institutions such as the Motor and Sloper Clubs in India Street, the latter of which he joined with the help of Hugh Cameron, who was known as the ‘Moudie’, an old Scots word for a mole. Cameron, a bookmaker’s clerk, knew Slater from his earlier visits to Glasgow in1901 and 1905. The two men now met almost every day not just to gamble but also to visit music halls and skating rinks. Slater also kept company with two of his countrymen, Max Rattman, a business traveler, and Josef Aumann, a diamond dealer. As one would expect from a professional gambler, Slater was in the habit of rising late and going to bed very late. This lifestyle suited Antoine who walked the nearby streets and brought men back to the flat. On Sundays though, the couple always stayed together at home, sometimes entertaining friends in the evening.

However, Slater never really intended to settle in Glasgow; he was not making enough money in the city. This could explain why he felt the need to pledge and offer for sale a number of items. Foremost amongst these objects, as far as Slater’s future is concerned, was a brooch which he had given to Antoine and which he pledged on 18th November with Alexander Liddell, at a pawnbroker shop at the east end of Sauchiehall Street. The manager of the shop, Peter Crawford McLaren, gave Slater £20 and, in early December, another £20. Although the shop knew him as ‘Oscar Slater’ from his earlier visits to Glasgow, he used the name “Anderson” in these transactions.

In America, on the other hand, business was very much better. According to Max Rattman, Slater arrived in Glasgow expecting to receive at any time an invitation from a friend in New York or San Francisco to cross the Atlantic. Slater certainly made no secret of his desire to return to America. He spoke of it to his close friends, to his fellow gamblers in the Sloper and Motor Clubs and to his barber. He even made a preliminary offer of his flat to Aumann, but without success. In mid-December, he showed Cameron a letter from Devoto which contained an invitation to move to California. Slater indicated that his address would be ‘c/o Caesar Café, 544 Broadway, San Francisco’.

It can be said that the most important days in our lives are those which arrive unheralded and pass by unnoticed, rather like a driver who takes a wrong turning and does not discover his error for several miles. This was certainly the case with Slater on 21st December 1908.

The day began eventfully enough with the arrival of two letters, one from a friend called Rodgers in London and the other from John Devoto in San Francisco. The intimations were not unconnected. From London, Slater learned that his wife was trying to locate him in yet another attempt to obtain money. The news from California was more welcome; Slater had finally been offered a job in San Francisco. Slater reflected on these letters and reached a bold decision. He would leave Glasgow for California quickly, indeed that very week.

There was a great deal to be done. He had to make arrangements for his flat to be taken over and he had to obtain some ready cash. He told his maid that she would have to go to London on the following Saturday and find another position there. He also told her to go to the laundry for the expensive shirt he had left there. He sent word to Antoine’s step-sister, Mrs. Freedman, who lived in London, telling her that she could move into his flat by the end of the week. He wrote to the Post Office asking for his savings to be sent to him at once, if possible by wiring. Around noon, he visited Liddell’s and pledged a further £30 on the brooch, bringing the total to £60. Around 4.30 that afternoon, he met his German friends, Aumann and Rattman in Gall’s public house in the Cowcaddens district of Glasgow. He offered each man the pawn ticket for the brooch. Both declined however because they felt that too much had already been pledged on the object.

At 6.12 that evening, he sent a telegram to the London watchmakers, Dents, asking for his watch to be returned immediately and not on 30th December, as previously agreed. He then walked up Renfield Street to rejoin his friends in Johnson’s billiard saloon which stood opposite the Pavilion music hall. He watched them play for a few minutes before leaving at about 6.30. He said he was going home for his dinner, as was his custom at 7 pm. As far as Rattman could recollect, Slater was then dressed in a dark suit of clothes and a bowler hat. Aumann remembered that Slater was wearing a waterproof overcoat.

At 8.15 that evening, Duncan MacBrayne, a shop assistant in a licensed grocers in Charing Cross, passed by Slater’s house on his way home and saw Slater standing only a few yards from his close in St George’s Road. To MacBrayne, Slater, who was not wearing an overcoat, did not seem intent on going anywhere in particular and was not acting in an unusual manner. Nor did the German appear agitated or excited. There can be no doubting the accuracy of MacBayne’s sighting, for he knew Slater as a regular customer to his shop. On this occasion though, the two men had no need to converse and MacBrayne passed by in silence to board a tram. Shortly afterwards, MacBrayne saw an ambulance wagon hurry past and he remarked on this to the tram inspector. It was this event which fixed the date of his sighting of Slater in his mind.

According to Gordon Henderson, the manager of the Motor Club at 26 India Street, Slater entered his premises at 9.45 that night. Henderson later claimed that Slater was short of cash and was hoping that the club would honour a cheque. However, Henderson refused to do so, pointing out that he was not allowed to loan money. Henderson suggested that Slater should approach Cameron who would most likely be in the Sloper Club next door.

The next four days passed in a flurry of activity. Slater finalised the closing of his Post Office savings account and the sale of his consols. He sent another telegram to the London watchmakers, Dents, urging them to return his watch. He asked Thomas Cook to book him a berth on the Lusitania which was to sail for New York from Liverpool on Boxing Day. However, the Glasgow office could not guarantee him the outside berth he wanted and he left, saying that he would obtain this from Cunard, the shipping line, when he reached Liverpool. He gave the pawn ticket for the brooch to Cameron and asked him to sell it on his behalf. Cameron failed to do so and returned the ticket to Slater. On Christmas Eve, Slater sent £5 from Hope Street Post Office as a Christmas present to his elderly parents in Germany. On Christmas day, Slater paid a final visit to his barber, Frederick Nichols. While he was being shaved, Slater mentioned that he was leaving Glasgow that night to sail the following day on the Lusitania for New York. When he left, Slater took with him the shaving tackle he had deposited with Nichols shortly after arriving in Glasgow. Nichols did not find Slater to be in the least excited.

Shortly after noon on Christmas Day, Mrs. Freedman, who was to take over Slater’s flat, arrived with a friend. They had come to Glasgow the day before and had spent the previous night at the Alexandra Hotel. When they entered Slater’s flat they found him busy packing. Slater had nine trunks and cases and these he filled carefully with his clothes and other possessions. He placed camphor among the garments to keep them fresh. They also found Antoine in tears because Slater did not want to take her with him. He thought the winter crossing would not suit her and that it would be best for her to stay with her family in France and join him in the summer. Antoine though wanted to accompany him and she cried until she got her way. Slater managed to borrow £25 from Freedman. He also arranged for Schmalz to stay behind and hand over the flat before she herself went off to London.

Sub-letting was technically illegal and this, coupled with the desire to avoid his wife, could explain why Slater instructed Schmalz to tell people that he and Antoine were going to Monte Carlo rather than America. In fact, he gave Monte Carlo as his destination to Freedman. It would appear that Slater wished to conceal the fact that he was leaving Glasgow for good from his landlord and the shop from which he had hired his furniture. Doubtless, he also wished to conceal from them the fact that he had handed over his flat to two prostitutes.

Between 6 and 7 that evening, Slater went to the Central Station in Glasgow and hired the services of two porters, John Cameron and John Mackay, to carry his luggage from his flat. The porters called at Slater’s place a few minutes past 8 p.m. after first mistakenly going to the top floor flat which belonged to Mrs. Margaret Fowlis. Slater supervised the loading of his luggage and sent the men off. He, together with Antoine and Schmalz, proceeded to the station by cab and met the porters there at around 8.45 p.m.

At the station, Slater’s luggage was handled by another porter, James Tracy. He saw Slater and his female companions arrive and opened the cab door for them. After claiming his bags from Cameron and Mackay, Slater told Tracey to have his luggage labeled for Liverpool as he was leaving for that city by the 9.05 train. Tracey complied and placed nine pieces of luggage in the rear brake van of the train, which carriage had been allocated for the effects of Liverpool passengers. Slater also asked Tracey to send a small parcel to Paris. As far as Tracey could see, Slater acted just like any other passenger, except that he was annoyed at having to pay an excess charge for his luggage.

Slater later maintained that a strange incident occurred at the excess luggage department. He said that he happened to see concealed there a man he recognized as a Police officer, in fact an officer who had apparently been watching his flat. A person like Slater, who lived on the borderline of the law, had naturally to be wary of the Police and suspicious of any attention they paid him. Slater did have a minor criminal record for fighting in a public place and illegal gambling. More importantly, he was known to the Police as a man who reportedly lived off prostitutes.

After obtaining their tickets and bidding farewell to Schmalz, Slater and Antoine boarded the 9.05 train for Liverpool. They arrived in the English port at 3.45 a.m. the following morning and got off the train there, the only Glasgow passengers to do so.

Slater had been seen off in Glasgow by a representative from Thomas Cook, and now, in Liverpool, he was met by James Robert Dustin from the local Thomas Cook office. Slater confirmed that he had not yet booked his passage on the Lusitania. He declined Dustin’s offer to help with the luggage and made his way to the adjoining L & NW Railway Hotel where he booked Room 139 for Antoine and himself under the name ‘Oscar Slater, Glasgow’.

Around 12.30 p.m. on 26th December, Slater entered the offices of John Forsyth, the passenger manager of the second-class cabin department in the Cunard Steamship Company, Liverpool. Forsyth, acting on information from Thomas Cook in Glasgow, had made a provisional booking in the name of ‘Oscar Slater’. However, Slater declined this berth and chose instead an outside stateroom which cost him £28. He purchased the berth in the name of ‘Mr. and Mrs. Otto Sando’. He explained, in jest, that he was ‘not Sandow, the strong man’. Forsyth handed Slater the application form required by US law and watched him fill it up there and then. Slater described Antoine and himself as ‘Otto Sando and Anna Sando’. Claiming American nationality, Slater said he was a dentist and gave his US address as 30 State Street, Chicago. Forsyth later maintained that Slater (or Sando) seemed rather nervous and kept looking at the door of the office as if he was expecting someone.

Before leaving the L & NW Hotel, Slater penned a quick note to his friend, Max Rattman. Giving the San Francisco address he had already used, Slater wrote,

Dear Max,

Surprisingly leaving Glasgow. Forgot to say goodbye. Let me hear from you As you have my address. Freedman’s girl took over my flat; keep yourself as well as your wife well, and remain,

Your friend,

O.Slater.

My French girl leaves for Paris from here. I will inform you over certain matters regarding San Francisco later. Tell Carl Kunstler, Soldata, and Willy, and respectfully Beyer to write. You can also make inquiries whether Beyer has paid the £15. He looked very pale latterly.

Best wishes to Soldata, Kunstler and Willy.

As is to be expected at the height of winter, the Atlantic crossing was a rough one. Slater, who told his steward, Thomas Atherton, that he had done the journey six times already, was not unduly affected. Antoine though suffered badly and she spent a large part of the voyage in their cabin, C1. Slater normally ate with the other passengers, but she took her meals in her cabin. There was doubtless great relief therefore when the Lusitania arrived off New York on 2nd January 1909.

This relief though was short-lived. Before the liner actually touched shore, six US detectives came on board from a customs vessel and arrested Slater. A search revealed the pawn ticket for Antoine’s brooch. The detectives explained that a communication had been received from the British government. Slater was wanted for the murder of Miss Marion Gilchrist. Slater appeared stunned.

Who, he asked, was Miss Gilchrist?

3

A Murder

St George’s Road, the street where Slater lived, runs in a northerly direction, effectively linking Charing Cross on Sauchiehall Street with St George’s Cross on Great Western Road, the main thoroughfare out of the city to the north-west. A few hundred yards north of Slater’s flat, St George’s Road is joined at right angles by West Prince’s Street which runs west, parallel to Great Western Road.

By 1908, West Princes Street had lost something of its status as a place to live, due to the increasing popularity of the most westerly areas of the city, but it was still a highly respectable district occupied by doctors, stockbrokers, businessmen and the like. It was a quiet street, especially at night, little used by anyone other than residents or visitors. Strangers were soon detected.

This was the case in late 1908 when some locals began to notice that a man had taken to loitering in the street. The descriptions of the man and the times of the sightings vary. The man’s purpose though apparently concerned No. 15 Queen’s Terrace and in particular the first floor flat which had been the home for the previous three decades of Miss Marion Gilchrist, an 82 year old spinster.

Queen’s Terrace is a two-storey tenement which stands on the south side of West Princes Street about 75 yards from its junction with St George’s Road. The building has a double entrance of two adjoining doors which are reached by five steps. One doorway leads to the ground floor flat, No. 14, which in 1908 was occupied by Mr. Arthur Montague Adams, a professional musician, his mother and five sisters. The other door, which is the one closer to St George’s Road, leads to the first and second floor flats. These flats are substantial, consisting of a large hall, dining room, drawing room, two bedrooms, parlour and kitchen. In 1908, the top-floor flat was empty, a fact which made Miss Gilchrist feel somewhat insecure, although she was glad that the stairs did not get so dirty so often.

Miss Gilchrist, the daughter of Glasgow engineer, James Gilchrist, was a tall, erect lady of a hardy constitution who looked and acted many years her junior. She was very well off and lived comfortably, but not extravagantly. Her one indulgence was jewellery which she kept in her flat in a locked box inside a locked wardrobe. The replacement value of this jewellery in 1908, when a man would have been fortunate to earn £150 per annum, was around £3,000. As is only to be expected, Miss Gilchrist took precautions that these jewels would not be stolen. When she went on holiday, she handed them to a neighbour or jeweller for safekeeping. She also told Arthur Adams, who lived immediately beneath her, that she would knock three times on the floor if she ever needed help in an emergency. Adams claimed that Miss Gilchrist lived in mortal fear of burglars and that she had asked him on several occasions to search her home for intruders. He had never found anyone, which is not surprising in view of the fact that the main door possessed three locks as well as a bolt and a chain and that the windows were always kept secure. In addition, Miss Gilchrist, by means of a lever in her lobby, had control of the door which gave access to her tenement from the street. It would have been very difficult for anyone to enter her flat without her permission.

Miss Gilchrist rarely had visitors; she spent by choice a somewhat solitary existence. In 1908, she lived alone with her maid, Helen Lambie, a 21 year old, high- spirited girl who came from the small Lanarkshire mining town of Holytown. Miss Gilchrist slept in the smaller of the two bedrooms. Lambie had a bed off the kitchen. Miss Gilchrist was on bad terms with her family and did not encourage visitors, especially men. She did not however forbid Lambie from having boyfriends and knew that she was friendly with a bookmaker called Patrick Nugent. He had been in Miss Gilchrist’s flat and had visited Lambie and the old lady when they were in the town of Irvine on holiday.

In considering Miss Gilchrist’s mysterious past, one is tempted to invoke the wisdom of the ancients who declared that ‘the evil doer fears the light’. There were rumours that she was a handler or, at least, a purchaser of stolen jewellery. There was another persistent rumour to the effect that the cloak surrounding Miss Gilchrist’s antecedents was meant to conceal not criminal activities, but behaviour which, within the dictates of her age, was nothing short of scandalous. This was although Miss Gilchrist had never taken a husband, she was no virgin and she had issue to prove it in the form of a previous servant called Margaret Galbraith.