Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

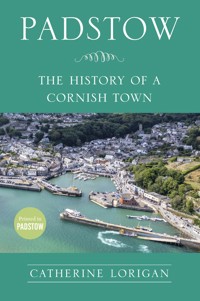

Padstow boasts a rich history spanning nearly 5,000 years. Here, its legacy is compiled through the centuries, from the legend of St Petroc's arrival on the north Cornish coast to build his famed monastery, through the expansion of Padstow's port during the medieval period and the rise of the shipbuilding industry in the early nineteenth century, to the arrival of the railway in 1899, which marked the beginning of a thriving tourism industry in Padstow. Today, modern Padstow remains a working fishing port, and the spectacular views of the Camel Estuary, the attractive harbour, narrow winding lanes, old cottages and the beautiful ancient church add to its charm. Padstonians are a close-knit community, some families having lived there for generations, who work to keep Padstow's traditions alive for many years into the future. Padstow: The History of a Cornish Town collates this long history, preserving the tale of a fascinating, resilient town.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 524

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FOR ALL PADSTONIANS

This book was printed by TJ Books in Padstow. TJ Books have been printing books at their factory on the Trecerus Industrial Estate for over 50 years and employ over 100 people. Books made at their factory are shipped internationally and produced for some of the UK’s largest publishers, including The History Press, the publisher of this very book. To find out more about TJ Books and the work they do in Padstow, please visit www.tjbooks.co.uk.

Cover photograph © by kind permission of Scott Fisher, [email protected]

First published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Catherine Lorigan, 2025

The right of Catherine Lorigan to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 83705 040 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

CONTENTS

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations and Currency

List of Figures and Plates

Map of Cornwall Showing Padstow and its Environs

Foreword by Peter Prideaux-Brune

Introduction

1 THE MONASTERY AND THE CHURCH

1. The Origins of Padstow – Sixth Century

2. The Parish Church of St Petroc, Padstow – Sixth Century

3. The Bells of St Petroc’s Church – Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

4. Chapels and Holy Wells – Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

5. The Probate Records of the Inhabitants – Seventeenth Century

6. The Poor Law – Seventeenth Century

7. The Churchwardens’ Accounts – Seventeenth Century

2 THE TOWN

1. The Origins of the Town – Tenth Century

2. The Prideaux Family – Sixteenth Century

3. Music, Carols and May Day – Eighteenth Century

4. Schools – The Boys, Girls and Infants – Nineteenth Century

5. Illness in the Town – Nineteenth Century

6. The Railway – Nineteenth Century

3 THE SEA

1. The Black Rock Ferry – Fourteenth Century

2. La Seinte Marie Cogg of Padestowe – Fourteenth Century

3. The Port Books – Fourteenth Century

4. The Quay, Quay Dues and the Harbour of Padstow – Fourteenth Century

5. Smuggling – Sixteenth Century

6. The Lifeboats – Sixteenth Century

7. Wrecks and Wreck of the Sea – Seventeenth Century

8. The Brig Sally – Nineteenth Century

9.Arrow and HMS Whiting – Nineteenth Century

4 VISITORS TO AND INHABITANTS OF PADSTOW

1. Inigo de Valderama – a Spanish Spy? – Sixteenth Century

2. Malachy Marten and the East India Company – Seventeenth Century

3. The Rawlings Family – Eighteenth Century

4. John Brett – Pre-Raphaelite Artist – Nineteenth Century

5. The Royal Merchant Seamen’s Asylum, Snaresbrook, East London – Nineteenth Century

5 LAW AND ORDER

1. The Nanfan and Calwoodley Families – Fifteenth Century

2. The Tudor Conquest of Ireland – Seventeenth Century

3. William Philp – Eighteenth Century

4. Corn Riots – Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Conclusion: The Future of Padstow: ‘From Fine Dining to Cool Cafes’

Bibliography (including archive abbreviations)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Born in London, Catherine Lorigan has degrees from the universities of Birmingham, Oxford and Exeter. Her love of Cornwall began during her teenage years and has led to its history becoming the focus of her research interests. The author now of four books on the county, including Padstow, her first book encapsulated the dual themes of the social and economic history of the village of Delabole. Based on her PhD thesis, this book was awarded the Holyer an Gof trophy in 2008 by the Cornish Gorsedh for the best book published about Cornwall in the previous year. Delabole was followed by Connections, which drew together a number of interlinking aspects of the history of North Cornwall. Her third book, Boconnoc, explored and studied the estate of the same name, situated between Lostwithiel and Liskeard and found in one of the least-known parts of Cornwall.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

To the following I extend my thanks:

In Cornwall: Peter and Elisabeth Prideaux-Brune; John Buckingham; the staff of the Courtenay Library, Royal Institution of Cornwall; Scott Fisher; Daphne Hicks; the staff of Kresen Kernow; the late Barry Kinsmen; Malcolm McCarthy; Joanna Mattingly; Kate Whiston (katewhisphotography.co.uk).

In the rest of England: the staff of the British Library; Liz Evans; Craig Lambert; Ann Darracott; Chris Pickford; Devon Archives; Royal Berkshire Archives; Royal National Lifeboat Institution; Rupert Maas and the Bridgeman Gallery; Françoise le Saux; the staff of the National Archives; the staff at The History Press; Joanna Luke.

LIST OF FIGURESAND PLATES

FIGURES

1. Watercolour drawing of the church font. Scrapbook, John Samuel Enys. (Kresen Kernow (KK): EN/2518/116)

2. Watercolour of the church font cover. (KK: EN/2518/91)

3. The church south aisle: pews in St Petroc’s Church, 1888. (francisfrith.com)

4. The bellringers in 1952. (Malcolm McCarthy Collection)

5. Valuation record. (The National Archives (TNA): IR58/71922, No. 473)

6. ’Obby ’Oss, 1920. (Royal Institution of Cornwall)

7. The new Padstow school designed by Sylvanus Trevail, 1876.

8. The opening of the railway to Padstow, 27 March 1899. (Royal Institution of Cornwall)

9. The Black Rock Ferry. (Malcolm McCarthy Collection)

10. The RNLI lifeboat Arab 1, 1883–1900. (Royal Institution of Cornwall)

11. The lifeboats, No. 2 Edmund Harvey with the tug Helen Peele, 1901. (Royal Institution of Cornwall)

12. A black and white engraved print illustrating a view of the mansion at Saunder’s Hill. Engraved by J.C. Stadler for C.S. Gilbert and published in 1817.

13. The boys of the Royal Merchants’ Sailors Orphanage c.1905.

14. Drawing of the Jane Lowden. (Illustrated London News, Saturday, 17 February 1866)

PLATES

1. Statue of young boy outside the church holding the armorial bearings of the Nanfan family.

2. The pall donated to the church in 1642 by John Vivian. (© Kate Whiston)

3. Map by Thomas Martyn, 1748. (© KK: AR/18/1)

4. Place House, Padstow. Seat of the Reverend Charles Prideaux-Brune, c.1835.

5. The mask of the ’Obby ’Oss. (© Royal Institution of Cornwall)

6. Padstow to Truro c.1724, based on John Ogilby’s maps of the 1670s.

7. The Doom Bar. (© Kate Whiston)

8. The site of the sinking of HMS Whiting. (Malcom McCarthy Collection)

9. Map of Bantam, a port town near the western end of Java, Indonesia.

10. Painting by John Brett of St George’s Well. (© Rupert Maas and the Bridgeman Gallery)

11. The buildings of the Royal Merchant Seamen’s Orphanage. (© mediastorehouse)

12. Birtsmorton Court. (© Worcester Federation of Women’s Institutes)

13. Painting of Mount Nelson, near Hobart Town, Tasmania, by Joseph Lycett (1825).

MAP OF CORNWALL SHOWINGPADSTOW AND ITS ENVIRONS

FOREWORD

IN MEMORY OF PETER PRIDEAUX-BRUNE 1944–2025

In 1704, my direct ancestor Humphrey Prideaux, Dean of Norwich, slightly unexpectedly inherited my home, Prideaux Place, Padstow and the surrounding district, his elder brother having predeceased him. All he said was, ‘I will never visit there again as it is a dirty smelly place!’ Not a very grateful reaction for this substantial windfall.No fishing villages had closed sewers in those days, so he stayed in the sophisticated town of Norwich in Norfolk until he died in 1724.

Padstow has a rich if tough history. For example, in the 1590s the Mr Prideaux of the time dabbled in a spot of legalised piracy and had not given Queen Elizabeth I her cut. His wife loyally shot in the neck the Commissioner sent to enquire, fortunately only wounding him. This disreputable incident is fully recorded in the Privy Council papers and was only resolved after years of litigation when the Crown got bored by deliberate delaying tactics and closed the books. However, there are gentler moments, as each year on 1 May there is an ancient Folk Festival which dances around the town and then to Prideaux Place to a tune that the composer Vaughan Williams, with his special interest in folk music, speculated might date from even as far back as Saxon times. Going further back in time, there was considerable speculation even as late as the twentieth century that Jesus along with Joseph of Arimathea had landed in Padstow on his way to Glastonbury (not for the festival!) Geographically, this would be entirely persuasive as Padstow was the start of the still extant Saints’ Way, across Cornwall, an arduous walk of a marathon’s length.

These last two instances may be legend, but the rest, as they say, is history. It is a surprisingly rich story from an originally barely literate little fishing community. There remain some real old Padstow families here … but read on.

Peter Prideaux-Brune

December 2024

INTRODUCTION

This book has taken far longer to appear than I would have wished. Unfortunately, the research was severely interrupted by the Covid pandemic when many archives, including the National Archives in Kew and Kresen Kernow in Redruth, were forced to close. When they opened again, sometimes it was on a restricted basis over many months, constraining any serious ‘research’ activity. Nevertheless, here it is at last.

There are many interesting books about Padstow on various topics. This book is different in that it is not a traditional history. Instead, it comprises a series of essays, articles and snapshots, some long, some short, vignettes if you will, with interlinking themes exploring different aspects of Padstow’s history, mostly chronological, but not always.

In some cases, where much has already been written, for example, the May Day revels, mention will be made for the sake of completeness, but will not be covered in any detail. Furthermore, I have made an attempt to find illustrations that may not be widely known.

As Peter Prideaux-Brune points out in his foreword, there remain ‘some real old Padstow families here’ who have lived in the town for generations. They will know yet more about Padstow than I could ever learn, but I hope that some of this may be new, even to them.

Finally, I would like to express my thanks to those Padstonians who have given up their time to talk to me, show me family and other photographs and discuss and reminiscence about their lives. Any mistakes are mine and this historian’s ‘voyage of discovery’ has been both a pleasure and a joy.

Catherine Lorigan

January 2025

1

THE MONASTERY AND THE CHURCH

1. THE ORIGINS OF PADSTOW

The origin of the settlement at Padstow can be dated to the foundation of a monastery in the sixth century by St Wethinoc. Wethinoc was subsequently supplanted by St Petroc and the church at the top of the town is dedicated to the latter. In about AD 518 Petroc arrived from Ireland where he had been studying, together with a group of followers and according to tradition, they crossed the sea in a coracle or on a mill stone.

There are two extant accouns of Petroc’s life. While they tell nothing about the conditions in the sixth century, they shine a light on the cult of Petroc in the medieval period. They tell us that Petroc was a Welsh prince, but chose to travel to be educated in an Irish monastery. In 518, setting out from Ireland with a band of followers, they sailed across the sea and landed at Lelissick on the bank of the Camel Estuary. After arriving in Cornwall, he met a hermit called Samson, who had a dwelling by the shore, then Bishop Wethinoc, who gave up his cell to Petroc and his followers, but asked that the place be named after him. It became Landwethinoch, an earlier name for Padstow. Petroc subsequently met a man called Guron, who also gave up his cell to the saint. Petroc travelled to Rome, Jerusalem and spent seven years on an island in the Indian Ocean.1

The earlier account, the Vita [I] Petroci, is found only in a manuscript, which is a complete copy in a sixteenth-century document of the abbey of Saint-Méen (Ille-et-Vilaine) in Brittany. The Vita [II] Petroci, probably dating to the fourteenth century, is in the Ducal Library in Gotha. The manuscript, which is of West Country origin, reports a series of miracles performed by Petroc. These included striking a rock from which water emerged for thirsty harvesters to drink and saving a stag from huntsmen, together with an account of the theft of Petroc’s relics, De reliquiarum furto.2

The current church is sited above the town and built into a steeply sloping site. Of the monastery founded before 981, nothing remains.3

In 1177, St Petroc’s relics were stolen by a monk called Martin. After it was found that they were missing, Martin fled to Brittany and hired a horse to ride to Saint-Méen. Arriving at the monastery and leaving the bones unattended, some boys opened the sack in which Martin had been carrying the relics. One removed a rib as a jest and handed the bone to the other boys. Immediately, their hands became swollen. Martin feared similar repercussions and confessed to the abbot. On learning where the relics were, Bartholomew, Bishop of Exeter, went to his friends at court, meeting Walter of Coutances, the sigillarius, the keeper of the Great Seal under Henry II, and asking the King to order the return of the relics. Walter departed with the King’s Messenger and an ivory shrine that had been purchased to house the relics. After a visit to Mont Saint-Michel and a lengthy perambulation around Normandy, the party returned to England. They met Henry II at Winchester and from there the relics were returned to Bodmin on 15 September.4

An Early Christian Cemetery5

In the mid-ninth century, West Saxon King Egbert gave three great Cornish estates to the Saxon Bishop of Sherborne. One of these estates was Polton or Pawton, which embraced all the northern part of Pydar Hundred, excepting only the town and immediate surroundings of Padstow. Until the 1820s, the parish was divided into Padstow Town and Padstow-in-Rure. Padstow town belonged to the Archdeaconry of Cornwall and the Deanery of Pydar, whereas Padstow-in-Rure was a Peculiar of the Bishop of Exeter and belonged to the Deanery of Pawton.

The manor of Padstow included the whole town, the advowson of the church and rectorial tithes, rights over the River Hayle from the quay to the mouth (possibly an earlier name for the River Camel). After the move to Bodmin, the monks of St Petroc continued to own the manor.

In 2001, Cornish Archaeology carried out excavations at the Althea Library, 27 High Street. The site is at the north-western edge of Padstow, near the parish church, just beyond the northern boundary of the churchyard and separated from it by Church Street. Seventeen graves were exposed, all aligned broadly east to west. Skeletons from three graves were removed and taken for radiocarbon analysis, which indicated an eighth- or ninth-century date for the cemetery.

It was believed initially that the monastery buildings were to the south of Prideaux Place, but further examination has concluded that it was closer to the parish church. The graves form a curve and mark the western end of the burials, which also forms a continuation of the western boundary of the church. The priory grange or farm is believed to have been on the site now occupied by Prideaux Place.

On the site, the burials include not only men, but also women and a child. These could be lay members of the community attached to the monastery or inhabitants living in the local area for whom the monastery supplied pastoral care. The buildings may have expanded in extent and the area become an archetypal Celtic monastery, with an infirmary, library and cells for the monks.

The Bodmin Gospels and Manumissions

The Bodmin Gospels were created in Brittany in the late ninth century. By the end of the tenth century, the volume was to be found at ‘the priory of St Petroc’. While the priory was originally located at Padstow, by 981, it had moved to Bodmin, possibly after a Viking raid on the north coast of Cornwall:

981. In this year St Petroc’s-stowe [Padstow] was ravaged …6

Between the 940s and 1025, public manumissions, ‘at the high altar of the church of St Petroc’, recording the freeing of slaves were written in some of the margins of the gospel book. The book is mainly in Latin, but with some Old English and Cornish, and thus an important source for early medieval Cornish history.7

It is not clear whether ‘the high altar’ mentioned in the Gospels was in Padstow or Bodmin. From the 950s to 981, it is suggested that the manumissions took place at Padstow and thereafter in Bodmin, where no altar to the saint was known prior to 981.8 A tract on the resting places of the saints drawn up approximately twenty years after the Viking attack stated that St Petroc’s body remained at Padstow. The removal may have taken place by 1086, for in Domesday Book, Bodmin was recorded first and Padstow second in the list of properties owned by St Petroc’s Church. Oliver Padel believes that it was not until the mid-twelfth century that there is evidence that Bodmin had become the home of the relics.9

There is an entry in the gospel book, dating from prior to 981 from which it can be assumed that St Petroc’s altar was still in Padstow.10 There are four overlapping groups of people named in the entries: the slaves freed, the owners who are freeing them, the people for whose souls the action was done (usually the owners themselves), and finally the witnesses:11

These are the names of the women, Meduil, Adlgun, whom King Edmund freed upon St Petrock’s altar, before these witnesses, Canguedon the deacon, Ryt the cleric, Anaoc, Tithert.

(Date: 939x946, King Edmund.)

Domesday Book

In 1086, these were the possessions of St Petroc’s Church in Domesday Book:12

Bodmin: the church of St Petroc holds Bodmin (Bodmine) in 1086 [and held it in 1066,] It is one hide of land that never paid tax. St Petroc had 68 houses [burgenses] and a market.

Padstow: the same church [the canons of St Petroc,] holds Padstow (Lanwenehoc) in 1086 [and held it, Languihenoc, in 1066,]; it never paid tax [except for the use of the church, nisi ad opus ecclesiae.]

The Prior of Bodmin Seeks to Assert his Authority in Padstow

In the early fourteenth century, the Prior of Bodmin appealed to the King to confirm the rights that the priory had held ‘from time beyond memory’ in their liberty of Padstow. Until thirty-four years previously this had been the status quo until the Sheriff of Cornwall ‘wrongly distrained their provost to present cries at the foreign (external) hundred in infringement of their estate’. The Prior argued that they had confirmation of rights pertaining to Padstow in two charters, the first giving a general confirmation by Edward the Confessor and the second from King John, in the late twelfth century, confirming the lands, tenements and rights of the Prior and Convent of Bodmin.13

The Prior requested of the King that ‘all of their burgesses of Padstow be quit of all manner of tolls throughout Cornwall’, as they had until they were ousted by the sheriff, and further requested that they should continue their Thursday market and fair on the eve, feast and morrow of St Leonard, from which they had also been ousted.

The sheriff about whom the Prior was complaining was Stephen Heym, who held important secular posts and at different times was Sheriff of Cornwall (between September 1256 and June 1259) and Steward of the Duchy of Cornwall. It is unclear if Heym was attempting to remove some of the Prior’s rights that could then be transferred to the Crown.14

The King also confirmed the Prior’s rights to the fishery of the Allen and Camel rivers, an important source of revenue, but he stated that he would not grant to the priory any ‘new liberties’. They should come before the treasurer to have confirmation of their charter in its current form.

In 1302, in an appearance before the Justices of the Crown, the Prior defended his right to hold the assize of bread and ale. The ‘assisa panis et cervisiae’ regulated the price, weight and quality of bread and beer manufactured and sold in towns and villages and was enforced by the manorial lords.

In addition, the Prior argued that he was entitled to hear any breaches of the peace in Padstow. In the Quo Warranto hearing, the Prior asserted that ‘he and his predecessors had enjoyed these privileges since time out of mind’. He was successful both in maintaining his right to hold the assize of bread and ale and to hear breaches of the peace in ‘Aldestow’, that is, Padstow.15

The Prior of Bodmin was noticeably invested in defending his rights in Padstow. In the mid-fourteenth century the Prior appointed a reeve to ensure that their rights were respected and followed.16 Under prisage, the Crown had the right in English law to take 1 tun of wine from every ship importing from 10 to 20 tuns and 2 tuns from every ship importing 20 or more. No prisage was taken from the Port of Padstow (Oldestowe) which is called Patrikestowe:

Nothing because the men (of the said) town of Padstow and the bailiff of the prior of Bodmin do not permit the lord duke prince to take away any prisage or any profits in his ports of Cornwall there. Aney they say that that Water is thus free so they should take no prisage or any profits pertaining to the lord as it is proclaimed there.17

References to St Petroc by Later Writers

In 1478, William of Worcester (1415–c.1482), an English chronicler, found when he visited Cornwall that in the Kalendar of Bodmin Priory on 15 September the words were inscribed ‘Exaltacio Sancti Petroci’ (Exaltation of St Petroc), ‘Die exaltacionis Sanctae crucis’ (Exaltation of St Petroc on the day of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross). This was the anniversary of the return of the relics from Brittany, which was observed as a festival of the ‘first-class’, down to the Reformation. The First-Class festivals were the most important of the church year and the feast of a patron saint or a saint of importance in the parish were frequently designated First-Class.18

John Leland, in Part II of his Itineraria, wrote about Padstow:

This toun is auncient bering the name of Lodenek in Cornishe, and yn Englisch after the trew and old writings Adelstow. Latine Athelstani locus.

There use many Britons with smaul shippes to resorte to Padestow with commodities of their countery and to by fische.19

And about Bodmin: The paroch chirch standith at the est end of the town and is a fair large thyng.

S. Petrocus was patrone of this and sumtyme dwellyd ther.

The shrine and tumbe of S. Petrok yet stondith in thest part of the chirche.20

Sanctuary

Sanctuary in medieval England was a legal mechanism that allowed criminals to seek refuge in a church for up to forty days to escape arrest for serious crimes. Theoretically, any church could offer sanctuary, but at Padstow, St Buryan and Probus, the area within which sanctuary could be claimed covered a greater amount of land than in other parishes. The lands next to the church formed the ‘Liberty of St Petroc’ and Charles Henderson argued that it referred to the houses and land juxtaposed to the church, while Charles Cox believed that it included a leuga, a mile and a half from the church in all directions.21

If a criminal could reach the area designated as sanctuary, the justices, sheriffs, parish constables and tithing man could not arrest the suspected felon, but the tithing man had to send word to the coroner that right of sanctuary was being claimed.22 When the coroner arrived, the felon had to agree to ‘abjure the realm’ – to promise to leave the country and never return. He had to travel to a port and sail on the first ship that was leaving. From this point of view, Padstow was an ideal place in which to claim sanctuary. To reach the quay in Padstow only entailed a walk down the hill on a path that emerged into the harbour.

In the Assize Rolls of Edward I, Padstow was described ‘a nest of evil doers who rampaged around the surrounding countryside and when the constables and tithing men pursued them, they took refuge indefinitely in the sanctuary’. Between the years 1277 to 1283, twenty-one people were recorded as claiming sanctuary. These included John de Frelayn, a thief of many larcenies. He abjured the realm. He had no goods.

In other cases it was apparent that as soon as criminals had committed felonies, they put themselves in the Liberty of St Petroc at Oldestowe (Padstow) and stayed there, and when the coroner made abjurations of them, they moved freely within the Liberty, not keeping within the church.

Some of the criminals had goods. Robert Le Mascan put himself into the Church of St Petrocus de Yallestowe (Padstow) and acknowledged himself to be a thief, guilty of many thefts, and abjured the realm before the coroner. The same rolls record other thieves, including John Gyffand, a horse stealer, Henry Cheyton, an ox stealer, and Ralph Boshanquet, a murderer.23

Sir William Rastall, Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, in his ‘Collection of Statutes now in force’, London 1594, supplied a copy of the form of confession and abjuration that was usually employed. It is as follows:

This hear thou, Sir Coroner, that I of [name] am … a … and because I have done such evils in this land of our Lord the King, and shall haste me towards the port of [mentioning a port named by the coroner], and that I shall not go out of the highway, and if I do, I will that I be taken as a robber and felon of our lord the King, and that at such place I will diligently seek for passage, and that I will tarry there but one flood and ebb, if I can have passage, and unless I can have it in such a place I will go every day into the seas up to my knees assaying to pass over, and unless I can do this within forty days, I will put myself again into the church as a robber and a felon of our lord the King, so God me help and His holy judgment.24

The Edwardian Inventories of Church Goods in Cornwall

In 1552, inventories of church goods were taken by the Commissioners of the Crown, appointed to make inquiry respecting church goods and ornaments. They had to take notice of all manner of ‘goodes, plate, juells, vestyments, bells and other ornyments within every paryshe belonging or in any wyse apperteyning to any church, chapel, brotherhed, gylde or fraternytye within this our realme of England’.

After the dissolution of the monasteries, the commission was entrusted to stop embezzlement of the church goods by private citizens. Another commission ordered that the valuables should be seized, ‘for as muche as the King’s Majestie had neede presently of a masse of mooney’ with only a few items left for the church. If money was made from goods that were disposed of locally, the proceeds had to be sent to the Treasurer of the Mint. When Mary came to the throne (1553–58), she reversed this policy and ordered that church goods should be returned to their respective parishes, although it not clear what goods were left to be returned.25

The inventory taken for Padstow in 1552, listed the following items:

Pydar Hundred.

Paddistowe Recevyd ther iij challis

with Patens of

xlv onces

xx ij onces

A sensor of sylvr of

xxxj onces

iiij

And a Pax of sylvr of

vj onces

& Redeliv’d

NOTES AND REFERENCES

1. Lynette Olson, Early Monasteries in Cornwall (Boydell & Brewer, 1989) p. 67; the place name element lann refers to the monastic enclosure or the estate in which it stood; Dmitry Lapa, ‘Venerable Petroc of Cornwall’, 17 June 2014 (orthochristian.com/71371.html).

2. Jankulak, Karen, The Medieval Cult of St Petroc (Boydell & Brewer, 2000) p. 2.

3. ‘The Church of St Petroc’ pamphlet on sale in the church.

4. Jankulak, The Medieval Cult of St Petroc, pp. 20–21, 192.

5. Pru Manning and Peter Stead, ‘Excavation of an Early Christian Cemetery at Althea Library, Padstow’, Cornish Archaeology, Vols 41 & 42 (2002/03) 80–106; Henderson, 1958, p. 373.

6. J.A. Giles (ed.), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (London: G. Bell & Sons Ltd, 1914).

7. British Library (BS): Add MS 9381.

8. Oliver Padel, Slavery in Saxon Cornwall: the Bodmin Manumissions Hughes Memorial Lectures 7, Hughes Hall & Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic, University of Cambridge (2009) p. 6.

9. Ibid., pp. 6–7.

10. Ibid., p. 9.

11. Ibid., p. 8.

12. Jankulak, The Medieval Cult of St Petroc, p. 203; Exon: the Domesday Survey of South-West England, fo. 202a2, 202a3, p. 183 (www.exondomesday.ac.uk).

13. Petitions to King from the Prior of Bodmin in the National Archives (TNA): SC8/323/E565; TNA: SC8/324/E630; TNA: SC8/324/E631.

14. keaparishcouncil.org.uk

15.Placita de Quo Warranto, edited by W. Illingworth and J. Caley (London: Ayre & Strahan, 1818), p. 110. Placita de Quo Warranto means ‘by what warrant?’ and is a prerogative writ to try by what right parties held or claimed manors, liberties, privileges, etc. It is issued by a court, which orders someone to show what authority they have for exercising some right they claim to hold.

16. Maryanne Kowaleski (ed.), The Havener’s Accounts of the Earldom & Duchy of Cornwall, 1287–1356 (Devon & Cornwall Record Society, 2001); Calendar of Patent Rolls (CPR), 1343–45, pp. 572, 577.

17. Kowaleski, The Havener’s Accounts, p. 156; Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1339–40; TNA: SC6/816/12.

18. Latin Mass Society (lmswrexham.weebly.com); William of Worcester, Annales rerum Anglicarum.

19. Lucy Toulmin Smith (ed.), The Itinerary of John Leland in or about the years 1535–1543 (1907), pp. 179–80 (available at archive.org and melocki.org.uk).

20. Toulmin Smith, p. 180.

21. Reverend J. Charles Cox, The Sanctuaries and Sanctuary Seekers of Medieval England (George Allen & Sons, 1911) pp. 220–26, pp. 298–301.

22. The tithing man was responsible for the ten members of the tithing in his village and led to the view of Frankpledge, where all members of the tithing shared joint responsibility for everyone else.

23. Barry Kinsmen, Fragments of Padstow History (Padstow Parochial Church Council, 2003) pp. 7 & 8.

24. elfinspell.com

25. Lawrence S. Snell, Edwardian Inventories of Church Goods for Cornwall (Exeter, 1955) p. 49.

2. THE PARISH CHURCH OF ST PETROC, PADSTOW

A visitors’ guide can be purchased in the church and listed here are only some of its most interesting features and history.

Over a period of 1,400 years, there have been three churches on the site. The earliest fabric identified is of the early twelfth century or thirteenth century and the church was substantially rebuilt in the fifteenth century.

The lower half of the tower, part of the second church, is dated c.1100. Between 1425 and 1450, the church was rebuilt by, among others, John Stafford, a mason living and working in Padstow, and John Hopkyn, mason (fl. 1450). In 1450–51, a case was held in the Manor Court between a helier or roofer and the vicar, suggesting that at that date, the church roof was being re-slated. In 1440, forty days indulgence was granted to those parishioners who contributed to the upkeep of the church, the lights, candles and ornaments.1

The Interior of the Church

A holy water stoup, a piscina, is on the wall, placed to the right of the altar. The carving is of no great quality, but it is believed to be a representation of St Petroc, who is wearing a monk’s habit with a deer or wolf lying at his feet.2

The Font

The font, dating to the late fifteenth century, is some of the best work of the period in Cornwall. Nothing is known of the carver, although he is believed to be the so called ‘Master of Endellion’. His work is known at other churches, not only at Padstow and St Endellion, but at St Issey and St Merryn.

The font is made of ‘Cataclew’ stone, quarried from the cliffs close by Trevose Head. At each of the four corners, an angel is depicted holding a book. In addition, there are carved representations of the twelve Apostles, three on each side, all holding an item by which they can be identified.

There was once a superstition in Padstow that no one who had been baptised in the font would be hanged. This belief turned out to be without foundation for, in 1787, a man named James Elliott, who had been baptised in the font, was executed for highway robbery. He was found guilty of robbing the mail from James Osborne in the parish of St Clement on 11 January 1787. He stole a leather portmanteau (valued at 2s) and six leather bags (these were valued at 3s), property of the King.3

A watercolour drawing of the font in the church, John Samuel Enys’ Scrapbook (Kresen Kernow (KK): EN/2518/116)

The cover of the font. (KK: EN/2518/91)

The Sherborne Mercury reported:

The 24th ult. came on at Launceston, the assizes for the cunty [sic] of Cornwall, when James Elliott (aged 18), for robbing the mail, was capitally convicted, and sentenced to be hung in chains; but on account of his having discovered the place where the mail bag with the letters was, namely, in a tin shaft in the Parish of Padstow, that part of the sentence which related to his being hung in chains was remitted.4

The Nanfan Chantry Chapel in St Petroc’s Church

The Lady Chapel, which formed the south chancel aisle of the church, was built as a chantry chapel for Sir John Nanfan. A chantry chapel was endowed for the singing or saying masses for the soul of the founder after his death. This chapel originally had a solid screen and the space was reserved for requiem masses or the Officium Defunctorum (Office of the Dead) said for the repose of the soul of the decedent.

Outside, on the buttresses, are stone carvings. In the middle is a male figure, dressed in a short tunic. He is carrying the arms of the Nanfan family on a shield: sable, a chevron ermine between three wings argent. These are the emblems associated with King Henry VI and the chapel was erected by John Nanfan of Tregerryn in Padstow and Birtsmorton in Worcestershire. On the right is a headless lion with a mane, while the one on the left is either a hart, unicorn or yale (a mythical goat-like creature with horns and tusks of a boar), which has a collar, chain and hooves [Plate 1].

Brasses

To the left of the chancel step is found a half-effigy brass of Lawrence Merther, vicar. He was the incumbent when the church was being planned but he died in 1421 and did not see it completed. He and his clerk, John Retyn, were involved in the transfer of lands in October 1410, in Perlees, Trevanson, Roskear and Bodellick in St Breock.5

The Pulpit

The pulpit has been dated to c.1530 with objects associated with Christ’s Passion depicted in the carved panels.

Saint James the Great was martyred in Jerusalem in AD 44. According to one legend (and there are several), James’ body was transported to Spain on a boat made of a single scallop shell. To reach the city around the tomb of St James, a pilgrim trail, known as the Camino, was created after the discovery of the relics of St James at the beginning of the ninth century and was a major pilgrim route from the tenth century onwards.

At the top of each panel on the pulpit there are carvings of a scallop shell taken as the emblem by the pilgrims who travelled to the shrine of Santiago de Compostela, in north-west Spain, the culmination of the Camino de Santiago route. As Peter Prideaux-Brune writes in his foreword, the Saints’ Way is still extant, starting in Padstow and crossing mid-Cornwall from coast to coast, covering approximately 30 miles.

The Prideaux Memorial

In the south-west corner of the church there is a memorial to Humphrey Prideaux, his wife and Nicholas, John, Edmund and Humphrey, their four sons, all depicted in Jacobean dress. Higher up, there is a memorial to Sir Nicholas Prideaux (1550–1627) of Soldon in Devon, which was placed here after being moved to Padstow in 1732 from West Putford in Devon. Nicholas built Prideaux Place in 1592.

The Windows

In 1651, the churchwardens complained of the ‘charges being more than ordinarie by reason of the greate decaye of the church’. Over £5 was spent on window repairs, suggesting that medieval glass had been destroyed.6

Church Pews

Decades ago, churches had no seating. Members of the congregation could stand, kneel or move around as they wished.

In the 1620s, during the Counter-Reformation and led by Archbishop William Laud, he ordered all churches to be ‘pewed out’. This led to the custom of churches selling or renting pews and families paying for their pew, because a private pew conferred social status. The pews close to the front were more expensive and more sought after. Powerful families purchased box pews and considered them their personal property.

From the churchwardens’ accounts:

1638 of Elizabeth Brewen for hir Seate 2s.

Of John Rownseuall for him and his wifes seat 4s.

Of Petter Edwards for his wife seat 2s.

Of John ffenish for his seate 2s.

The church south aisle; pews in the church, 1888. (francisfrith.com)

In the 1840s, the payment of money for the right to rent and occupy a particular pew became a matter of contention in the Church of England. Citing ethical concerns, many Anglican churches outlawed the policy by the 1870s and many instituted open seating instead. Churches scrapped the practice, removed the box seats and replaced them with seats that could be occupied by any parishioner.

Funeral Rites – Churchwardens’ Accounts

Those in the congregation who wanted the knell, a bell, to be rung before and after a funeral service and the pall to cover the coffin would be charged. The man organising the funeral would provide the pall, the large cloth, which would be placed over the coffin from the time it was removed from the home of the deceased until it reached the graveside.

From the churchwardens’ accounts:

1638 For Cloth and Bell for Thomas Norton 10d

for Cloth and Bell for Katheren Murfild 10d

Of Oursela Smyth for hir Children knill [knell] 2s.

For 2 clothes and bell for the widow Cornish 1s.2d.

Music

Around the beginning of the 1700s, a number of churchgoers had become dissatisfied with the poor level of congregational singing. Choirs began to be formed, initially only of male singers. From around 1700 to c.1850, west gallery music became very popular. It was played and sung from wooden galleries facing the altar, mostly positioned at the west end of the church, hence its name, from which the choir and instrumentalists would perform.

A metrical psalm was translated into metre and rhyme to enable the Psalms to be sung to standard tunes during Christian worship. Many of the composers had no formal musical training, so often transgressed the rules of harmony, employing open fifths, false relations, consecutive fifths and octaves.7

If the singers needed help to maintain pitch and the church had no organ, a bass instrument was often employed as accompaniment. In some cases, as in Padstow, the conductor employed a pitch pipe to give out the notes. In April 1744, 1s was paid for a box and lock in which the singers could keep their pitch pipe.

Later, small bands were formed that mostly consisted of flexible instrumentation, often flutes, clarinets, bassoons, cellos and violins.8

A reminiscence from Barry Kinsmen records his membership of the Padstow choir:

The church was bitterly cold for choir practices in the winter. The cold air, so we were told, would produce good singing and often we could see our breath in the chill of a winter’s night.9

The Gallery

Galleries in parish churches are now unusual, but before the ‘restorations’ that took place in many churches, they were frequently used for church ‘orchestras’ and the precursors of organs. In the early nineteenth century, worship was accompanied by a small band of ‘musickers’ who were seated in the gallery at the back of the church.

In 1817, it was decided that a gallery should be built in the church, to be paid for by subscription from the inhabitants of the town and parish. The list was headed by Charles Prideaux-Brune, who donated £21, while William Rawlings, the vicar, gave £10 10s. There were other prominent members of the town, for example, ship-builder John Tredwen and Thomas Rawlings, who gave various sums. In total, £55 14s was raised and a gallery was constructed in February 1817.10

The gallery did not remain in the church for many years. Victorians disapproved of the Georgian galleries, and most were removed during restorations in the nineteenth century. Between 1855 and 1857, a restoration took place at Padstow and the West Gallery was dismantled. The church was restored mainly at the expense of Miss Mary Prideaux-Brune, when the old box pews were removed.

The most significant change of the nineteenth century was the reorganisation in 1888–89 of the chancel.11 The vicar informed the churchwardens that Mr Prideaux-Brune and his predecessor had undertaken the repairs of the chancel for many years previously. He had called on Mr Brune, and found it met with Mr Brune’s approval to restore the chancel. The churchwardens applied for a faculty to put into practice the whole scheme of restoration for the church according to the plans submitted by Mr J.D. Sedding. The organ, which was completely rebuilt in 1888 and 1893, was moved to the north chancel aisle, stalls for the choir were constructed, the vestry was expanded and seats were moved to face the altar.

The Church Pall

A pall, used to cover the coffin, was donated to the church in 1642 by John Vivian. Made of Italian silk velvet, it originally had a crimson silk lining. The inscription in the centre reads: ‘The gift of John Vivian of Padstow Gent, Jane, Olive and Katherine his daughters 1642.’ [Plate 2].12

Barry Kinsmen suggests that the pall was left in the hands of one of the parishioners not long after it was gifted to the church. This was to ensure that it was preserved and not damaged by Cromwell’s army during the Civil War in the 1640s. In the event, neither Oliver Cromwell, nor any of his soldiers, were recorded as having been present in Padstow. However, the Prideaux family of Prideaux Place initially supported Cromwell, but later changed their allegiance to the Royalists.

The Present Church

The church today is a benefice in transition. It provides a hub for community activities, hosting, among other things, children’s groups, other small groups and regular concerts. The church has been at the heart of Padstow for centuries and remains so.

The parish website is www.padstowparishchurch.org.uk

NOTES AND REFERENCES

1. Personal communication from Dr Joanna Mattingly.

2. A stone basin near the altar in Catholic and pre-Reformation churches for draining water used in the Mass.

3. britishexecutions.co.uk, execution at Bodmin for highway robbery, dated 10 April 1787.

4.Sherborne Mercury, 2 April 1787, p. 3. Hanging in chains is a practice in England where the body of a criminal who had been executed was hung by chains near the place where the crime was committed, the final part of the punishment. It denied the corpse a burial: thearchaeologist.org

5. Kresen Kernow (KK): Arundell family papers, AR/1/382, 1 October 1410; KK: AR/1/383 & 384, 2 October 1410; KK: AR/1/381.

6. Personal communication from Dr Joanna Mattingly.

7. Nicholas Temperley, The Music of the English Parish Church (Cambridge University Press, 1983) p. 196.

8. Barry Kinsmen, Good Fellowship of Padstow (Fellowship of Old Cornwall Societies, 1997) p. 75.

9. Kinsmen, Good Fellowship, p. 74; KK: Churchwarden’s accounts, P170/5/2; churchtimes.co.uk.

10. KK: P170/6/10/5, Churchwardens’ accounts (14 February 1817), receipt, tenders and subscription list for erection of a gallery in Padstow Church, 1817.

11. padstowchurch.org

12. Barry Kinsmen, Fragments of Padstow History, pp. 43–44.

See also: Canon G.H. Doble,‘The Relics of Saint Petroc’, published online by Cambridge University Press, 2 January 2015, pp. 403–15. Originally published in Antiquity, Vol. 13, Issue 52, December 1939.

3. THE BELLS OF ST PETROC’S CHURCH

The Prayer Book Rebellion

The rising in 1549, known as the Prayer Book Rebellion or Western Rising was a revolt in Cornwall and Devon against King Edward VI and the imposition of Cranmer’s First Book of Common Prayer. Replacing the Latin Mass and in English, it encompassed the theology of the Protestant Reformation. Humphrey Arundell (c.1513–27 January 1550), a Cornishman from Helland, was leader of the Cornish forces who opposed the introduction of the new prayer book.

In 1549, the Cornishmen advanced to Exeter and laid siege to the city, where they made the statement: ‘and so we Cornishmen, whereof certain of us understand no English, utterly refuse this new English’. Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, Lord Protector of England during the minority of Edward VI, sent John Russell to suppress the rebellion. The revolt was crushed and Arundell was captured, found guilty of treason and condemned to be hanged, drawn and quartered. He was executed on 27 January 1550 at Tyburn. This was reported in The Chronicle of the Grey Friars of London: ‘The xxvii day of the same monyth [January], was draune from the tower of London un-to Tyborne iiii. persons, and there hongyd and quarteres, and their quarteres sette abowte London on every gatte; thes was of them that dyd ryse in the West cuntre.’1

On 12 September 1549, the King’s Council wrote to Russell ordering him to take down the bells from every church in Devon and Cornwall, all bar the smallest of each peal. Arundell had taken up arms against the King and the church bells in Cornwall had been used to summon the rebels. It was considered that the sale of the bells would go some way towards defraying the cost of putting down the rebellion. The letter read:

After our right hartie comendacons to your lordshipp, Where the rebells of the cuntrye of Devonshyre and Cornwall have used the belles in every parishe – as an instrument to sturr the multytude, and call them together, Thinkyng good to have this occasyon of attempting the lyke hereafter to be taken away frome them, And rememberyng with all, that by taking downe of them the kyng’s Majesty maie have some comoditie towards his great charges that waye, we have thought good to pray yor good lordshipp to give order for taken downe the sayd bells in all the churches within those two counties; levyng in every churche one bell, the lest of the ryng that nowe is in the same, which maie serve to call the paryshoners togethers to the sermons and devyne servis; in the doyng hereof we require yor lordshipp to cause such moderacon to be used as the same may be done with as moche quietnes and as lytill force of the comon people as maie be. And thus we bid your Lordship most heartily farewell. From Westminster 12 Sept. 1549. Your Lordship’s assured loving friends, E Somerset [and others.]

And further the said counsail dothe in his Maties name promise like rewards to any man that shal apprehend or give knowledge of any person that by ringing of any bells, striking of dromme, proclaim bill or letter or any other waye shal labor to styrre the people and to make them rise, whereby there might growe uprore and tumult to the daunger of his Maties and of the state of and comen wealth of this same Realme or to the slaundr of the kings Maties said counsail.2

As (sadly) no inventories survive for Cornwall for the relevant period, it is not known whether this order was carried out and bells removed. Evidence from Devon suggests that some were, but that it did not take place universally across the county. As Somerset’s directive applied to both Devon and Cornwall, it can be argued that the condition of the Devon bells relates similarly to Cornish belfries and the bells were mostly left untouched.3

The Church Bells of St Petroc’s, Padstow

In the Padstow churchwardens’ accounts dating from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, many references are made to the costs that were expended on the bells. Not only were they maintained in good order, but the bellringers were rewarded with beer and money payments for ringing at festivals, when battles were won, for royal birthdays and on important days such as 5 November and Christmas Eve.4

Although it cannot be accurately ascertained when bells were first installed in St Petroc’s, it is likely that there were bells there from medieval times, probably three or four on the evidence of the ‘norm’ in the Edwardian inventories. However, written evidence shows that the church had bells from at least the mid-seventeenth century. Nicholas Watts, a resident of Padstow, was a ‘Midshipman in the good shippe London’. In his will, dated 2 August 1632, he left the sum of 12 shillings to be paid to the St Petroc’s ringers annually so that they would ‘ringe a peele in memory of my gifte’ on the anniversary of his death. He died on 21 August in 1632.5 This became known as the ‘Watts Knell’.

In August 1899, the ancient custom of ringing the muffled peal had taken place shortly before 5 a.m., no doubt somewhat surprising the parishioners.6

The churchwardens’ accounts, surviving for the parish from 1638, list numerous items of expenditure relating to the upkeep of the bells.7 Payments were made to the parishioners who were in charge of the maintenance and keeping the bells’ equipment and materials in good order. Disbursements were for (among other things) ‘oyle and grease’, iron work, bell ropes, tallow and for mending various parts of the bells. The following are some examples:

1638

£ s d

for the 4 Colla[rs] of the Belles

01.06.08

for the mendinge of the Clap of the second belle

00.05.06

for nayles about the stockes of the Belles

00.00.04

for oyle about the belles

00.00.03

Paid for a brace for the great bell

00.04.00

The 5th November for Ringgers8

00.04.00

for a new rope for the great Bell

00.05.06

1639

Tho: Enstice and his 2 men for worke about the Church and Bells

00.05.10

John Pearse for a new belroppe

00.05.06

1640

for tallow for the bell ropes

00.00.04

for twyn to mend the belcollers

00.00.04

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, more than half the bells in Cornwall were recast by just two families of bell founders. These were the Penningtons of Exeter, Bodmin and Lezant and the Rudhalls of Gloucester. They were the best-known bell founders in the West Country. Between c.1625 and 1720, the Pennington family had a foundry at Paul Street in Exeter. The casting room was built against the back of the city walls, while in front of it stood a cobbled courtyard with lean-to structures on three sides, in a narrow tenement.9

For many years, a strip of land immediately adjacent and running around the inside of the city walls had been kept clear for the purposes of defence. By the mid-seventeenth century, the authorities decided that this was no longer a priority and several leases were taken by businesses of these small strips of land at the end of their premises. The Penningtons were one such of these and thus they added a small addition of land to their foundry site. Annular foundations of stone were found in the casting pits at the Pennington foundry site, onto which the clay mould of the bell was built.10

In 1663, members of the Pennington family were employed to cast new bells at Padstow. The churchwardens at the time were Nicholas Harris and Thomas Martyn and in the disbursements are the following entries:

Paied Edward Pennington att his first coming

2s.6d

Paied to the Bellfounder in part payment for casting the bells

£14.00s.00d

for expences agreeing with the bellfounder

2s

to Perran Cardell 12 daies worke attending the Bell founder

12s

1st August 1664 since the above accompt paied to the Bellfounder in part

£1.3s.7d

1664 The next churchwardens, Justus Marsh and Gregory Rounsevall, ‘pd Thomas Pennyngton the Bellfounder the remainder of his money’

£4.5s

In addition, the following items in the accounts are listed as payments due to parishioners for their work on the bells:

£ s d

John Edwards for 2 staples of Iron used about the Bells

00.05.00

72 lb of Iron used about ye stocke of ye bells

01.10.00

for plate and Nayles about casting ye Bells

00.04.06

for 33 lbs of Hempe to make 3 Bell ropes

00.13.09

to Ralph Pearse for making the saide rope

00.04.04

to Nicholas Hitchings for 8 daies worke about the Stockes of the Bells

00.13.04

to Richard Lucas for a peece of Tymber to make a stocke for the great bell

00.05.06

for charges for haystering [hoisting] the bells

00.06.06

These two members of the Pennington family, Edward and Thomas, are difficult to identify. There was a Thomas Pennington based at Tavistock between 1653 and 1699, but in the family history there is no mention of an Edward Pennington, although he was, no doubt, a member of the same family.11

The Pennington bells were still in St Petroc’s Church in 1716. In that year, another member of the Pennington family, Christopher, entered into Articles of Agreement with the then churchwardens, Peter Swymmer and Peter Martyn. The document, dated 19 June 1716, agreed that Christopher Pennington would be paid 20 shillings yearly at Easter to ‘well and truly repair and keep the five bells now in the Tower of Padstow sound and in good repair as well in good and substantial collars hanging wheels as in all other Timber and Iron work and find and provide all materials and utensils needful for repairing and keeping the same (Except Ropes) during the said Term at his own Proper Cost and Charges.’12 Under the terms of the agreement, Pennington was due to continue these repairs for the rest of his life.

The next family of bell founders employed by the churchwardens were the Rudhalls. The family’s bell foundry in Gloucester was established in the later seventeenth century by Abraham Rudhall. John Rudhall took over the business in 1783 and received enquiries about casting bells from a wide area, mostly within the western half of the country, including in Cornwall, St Columb, Mawgan and Padstow.

An agreement was reached with Rudhall about recasting and the old bells were taken down and put on board ship. On 9 February 1798, an amount of £1 7s 6d was charged for the ‘Old Bells’ to be taken down and £1 1s for ‘freight of the Old Bells’ to Bristol and thence to Gloucester.13

On 18 March 1799, Rudhall submitted an account of his charges to Henry Mitchell and John Horswell, churchwardens. Hanging the new bells cost £70 and the cost, in total, came to £162 11s 1d.14

On 6 April a further amount of £1 7s 10d was paid for weighing the new bells and bringing them to the church tower and an amount of 13s 10d was paid for beer ‘in getting up the Bells and work done in the Tower’.15

Rudhall wrote from ‘Glocester’ on 9 April 1799 to the churchwardens, saying, ‘I am extremely happy to find the Bells are arrived safe for I had fears respecting them the weather has been so uncommonly tempestuous – to your request I have sent the account and the Bellhanger will set out within a day or two … and I hope that the Bells will answer to your satisfaction.’16 Another letter from Rudhall dated 18 May 1799: ‘I am extremely happy to find the Bells etc are to your satisfaction and if nothing unforeseen prevents me I intend doing myself the pleasure of seeing you soon as my Man informs me there are several Bells wanted in your neighbourhood.’17

In order to pay for the recasting of the bells, a subscription had been taken up from the inhabitants of Padstow. The list was headed by the Rev. Charles Prideaux-Brune and Mrs Brune, who contributed 5 guineas. Other donations from all over the town resulted in a total raised of £25 2s 6d.18

More than thirty years later, in April 1833, Rudhall was contacted by churchwarden Matthew Courtenay because the third bell had cracked. Rudhall wrote on 18 April 1833 about the price of a new bell, which would require tuning to the others. He wrote that he recollected with pleasure his kind reception at ‘St Merrins’ and Padstow about the year 1798 and he would use his utmost endeavours ‘to recast your third Bell in the best manner and within two or three weeks from the receipt of the old’. He suggested that the cracked bell be sent by sea. ‘I understand from Mr John Hawkin of your Town that the facility of carriage between Padstow and Gloucester is now very great. Vessels regularly trading every week.’19

Once the bell had been received in Gloucester, Rudhall wrote that he had received the broken bell, but he could not ascertain its ‘real note’. He asked Courtenay to send him a tuning fork with the note of the tenor bell ‘or if that can’t be easily done of either of the others below the cracked third’, so that he could design the mould and cast the new bell ‘in sound with the rest of the Peal’.20

A bill was forwarded for the recasting of the bell, which Rudhall said ‘appears to have a most musical sound and is tuned exactly to agree with the fork …’ The cost was £40 8s 8d, but £27 18s 3d was allowed for the old bell, leaving £12 10s 5d to be paid.21

John Rudhall represented the firm until about 1835, when the business was transferred to Messrs Mears & Stainbank. Thomas Mears owned the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, although the bells still continued to bear Rudhall’s name and he may have been retained by Mears as an employee or manager. Rudhall died in February 1835. The Dorset County Chronicle reported that the whole number of bells made by Rudhall, including those that had been recast, probably exceeded 5,000. This celebrated foundry had made four peals of twelve, ten of ten, eighty-two of eight, 295 of six, and 131 of five.22

In 1844, Charles and George Mears took over from their father, Thomas, as master founders.23 Bell No. 3 was recast in 1846 and again in 1896 by Mears & Stainbank, Founders of London, while Bell No. 5 was recast in 1883.

The West Briton, dated 7 June 1883, reported that ‘the bells of the old parish church were to be recast and rehung’, although only one bell was recast, the fifth. There was probably an overhaul of the fittings.24 On 24 September in the same year, a bazaar was held at Prideaux Place in aid of funds for a new bell and repairs connected with the other bells, the belfry and the church clock.

In accordance with tradition, after Queen Victoria died on 22 January 1901, muffled peals were rung the following week before morning and evening services in memory of the sovereign.25

In the London Metropolitan Archives, there is a foundry plan dating from August 1909. This gives the following information:26