1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

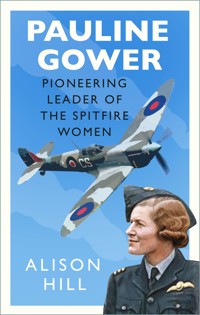

Pauline Gower was the leader of the Spitfire women during the Second World War. After gaining her pilot's licence at 20, she set up the first female joyriding business in 1931 with engineer Dorothy Spicer and took 33,000 passengers up for a whirl, clocking up more than 2,000 hours overall. Pauline went on to command the inaugural women's section of the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) and achieved equal pay for her women pilots. She enabled them to fly 'Anything to Anywhere', including Tiger Moths, Hurricanes, Wellingtons and – their firm favourite – the Spitfire. Pauline Gower: Pioneering Leader of the Spitfire Women is a story of bravery, fortitude and political persuasion. Pauline was a clear leader of her time and a true pioneer of flight. She died after giving birth, at only 36; a life cut tragically short, but one of significant achievements. Pauline left a huge legacy for women in aviation.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Alison Hill, 2022

The right of Alison Hill to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399148 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword by Maggie Appleton MBE

Introduction

Key Dates

Prologue – Flying On Ahead

1 Climbing Every Tree, Reaching for the Sky

2 Stag Lane – Learning to Fly, Breaking Records

3 Air Circus Summers with Dorothy Spicer

4 Piffling Poems for Pilots and Other Writing

5 Career Moves – Politics, Society and Aviation

6 Leading with Impact – Air Transport Auxiliary

7 Circle of Influence – Wartime Connections

8 Marriage, Birth and Lives Cut Short

9 Legacy – The British Women Pilots’ Association

10 Book Launch Circles – Harvesting Memories

Appendix I: The ATA Women Pilots and Engineers

Appendix II: Interviews Past and Present

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

FOREWORD BY MAGGIE APPLETON MBE

Alison Hill’s work on Pauline Gower MBE is a welcome addition to our appreciation and understanding of this true pioneer of flight. Alison highlights beautifully the inspiration that Pauline Gower and other leading female aviators provided for those around them and those who followed. Just as importantly, she has brought their passion for flight to the fore.

The valuable contribution of the women of the Air Transport Auxiliary has had a welcome spotlight shone upon it in recent years. However, Pauline’s place in its history is less widely known. Without her indefatigable determination, laced with charm and diplomacy, the women’s section may never have been born. Certainly this pioneering operation is unlikely to have achieved the success that it did. Hers is an important personal story that was waiting to be shared more widely.

This work will be a fascinating read not only for those interested in aviation, but also for the general history lover. Moreover, it marks Pauline Gower’s quiet but resolute place in the panoply of women who have pushed forward the rights of women to be treated – and paid – equally.

Readers will also find some valuable lessons in leadership. Pauline’s political savviness and her warmth and humour shine through the pages of this work, as do all the characteristics that mark her out as a shining standard-bearer and trailblazer.

Maggie Appleton MBE CEO, The Royal Air Force Museum

‘For me, aviation is top-ranking among all the careers open to women. More than that, I would say that every woman should learn to fly. Psychologically, it is the best antidote to the manifold neuroses which beset modern women.’

Pauline Gower

INTRODUCTION

I first encountered Pauline Gower and the ‘Spitfire Women’ in Hampton Court Emporium, a meandering antique shop full of the dust of generations and glimmers of past lives. Unaware, like many others as I discovered, that women flew Spitfires during the Second World War, let alone Tiger Moths, Hurricanes, Wellingtons and many more types, I purchased the pristine copy of Spitfire Women of World War II that had caught my attention (Giles Whittell, 2007). The book provided a lively overview and sparked a major flight of research, which in turn led to a new poetry collection, Sisters in Spitfires, to commemorate the women pilots of the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) – their lives, flights and achievements, during and after the war.

I was lucky enough to have had the chance to talk to Molly Rose during the research; a telephone conversation clearly remembered – as clearly as she recalled her first Spitfire decades after flying it – and to meet fellow pilots Joy Lofthouse and Mary Ellis at White Waltham, the spiritual home of the ATA. Mary had celebrated her 100th birthday earlier that year, and as she signed her poem in the collection – ‘I AM the Pilot’ – she looked up as a classic car whizzed by and the thrill of remembered speed danced in her eyes. In May 2018 I was flown over to Sandown Airfield on the Isle of Wight to visit Mary and learn more about her ‘charmed life’ and her memories of Pauline Gower. Just four months later, I wrote a new poem for her memorial service in Cowes, when her wartime flying record was commemorated with a Spitfire flypast and a church packed to the rafters. It was an honour to read ‘Spitfire Salute’ from the ornate eagle pulpit at the end of the service. Mary admired Pauline and recognised the significance of her legacy.

This new biography explores the life of a strong and resolute woman of humour, wisdom and incredible bravery in the air; who encouraged other women to fly; who achieved equal pay for equal work in the ATA; and who proved herself a resourceful and diplomatic leader throughout the war. Pauline’s sense of humour, often self-effacing, shines through her own autobiography, Women with Wings, as I hope it does here. A copy of her photograph in the National Portrait Gallery, taken in 1937, hung over my desk as I wrote and her calm gaze, clear strength of character and general good cheer accompanied me along the flight path. It would have been thrilling to have been one of her passengers of the air circus years, or to have met her for a cup of tea or something stronger. She was an inspiration to many.

In his 40s, her son Michael Fahie researched Pauline’s life in detail to discover more about his mother from those who had known her best. His tribute, A Harvest of Memories: The Life of Pauline Gower MBE, was published in 1995, and there are only a handful of copies left in print. Michael sent me bound copies of letters that formed his research from August 1992 to May 1994, intriguing documents in themselves. We were both relieved when the packages made their way safely from Australia to London in 2021, with minimal lockdown delays. What struck me, as I read the rich correspondence between long-lost family members and friends, and from fellow ATA pilots, sadly no longer with us, was the enthusiasm, respect and warmth with which they all remembered Pauline; and the way in which each of them, from around the world, gave Michael new insights into the mother he and his twin brother never knew. Each letter formed a piece of a jigsaw that enabled him to gain a fuller picture of his mother’s extraordinary life. Extracts from those letters, from pilots, friends and family, are woven throughout as testament to Pauline’s character and her pioneering achievements for women in aviation.

This book aims to remind future generations of Pauline’s remarkable life and legacy, and to highlight her many amazing firsts and achievements in aviation and during the Second World War, in a life lived very much to the full. I am grateful to The History Press for helping to keep her life story and legacy alive to new generations.

I was always drawn to Pauline. Her composure, intelligent gaze and ready sense of humour flickering at the corners of her mouth. She was born into wealth and a life of advantages, but she used it to fuel her own passion and to encourage other women to seek the skies and to go further, to fulfil their potential. She learnt a great deal from her father’s long political career, but she had her own way of achieving goals. Timing was everything and her natural diplomacy was evident in the progress she made so quickly, at a time when women were not even allowed inside RAF planes, let alone ferrying them from factory to frontline bases throughout the war. Pauline’s influence is there in her clear gaze, her forthright pose, her no-nonsense attitude to most things. If you don’t try, you won’t succeed. Something surely that the nuns at her Sacred Heart School in Tunbridge Wells would have instilled; some gently, some with a firmer approach. Pauline’s practical and direct nature was to play a crucial part in her wartime role, as it did in the lives and careers of the 164 pilots she recruited as commandant of the Women’s Section of the ATA.

Pauline Gower’s legacy, and indeed that of her high-achieving partner Dorothy Spicer, lives on in those women still breaking boundaries, following their ambitions of learning to fly or to become engineers – pushing past barriers that still exist. And why not? Pauline would have asked with a characteristic twinkle and arch of an eyebrow. This book also highlights some contemporary women pilots, particularly members of the British Women Pilots’ Association, and some of their success stories are outlined in Chapter 9. Many have achieved personal goals, aviation highs and commercial success. Pauline would have been proud of them all – she firmly believed that every woman should learn to fly.

KEY DATES

22 JULY 1910 – Pauline Mary de Peauly Gower is born in Tunbridge Wells, Kent, the second daughter of parents Robert and Dorothy Gower.

1922 – Starts at Beechwood Sacred Heart Convent School in Tunbridge Wells.

16 JULY 1926 – Makes her first Holy Communion and is received into the Catholic faith.

19 JULY 1927 – A serious mastoid operation, for which Pauline was anointed beforehand, results in double pleural pneumonia and near death. She was left with weakened lungs as a result and could not take part in active exercise again.

1928 – Pauline leaves Beechwood but maintains close links with the school for many years.

SEPTEMBER 1930 – Gains her ‘A’ licence at the Phillips & Powis School of Flying in Reading.

1931 – Trains for her ‘B’ licence at Stag Lane Aerodrome in north London, where she meets engineer Dorothy Spicer and record-breaking pilot Amy Johnson.

Given a plane by her father for her 21st birthday and sets up in business with Dorothy, initially running an air-taxi service in Kent.

MAY 1932 – Joins the Crimson Fleet Air Circus summer tour.

1933 – Pauline and Dorothy tour the country with the British Hospitals’ Air Pageant, visiting 200 towns.

1934 – Publishes a collection of poetry, Piffling Poems for Pilots, alongside later short stories for Chatterbox and Girl’s Own Paper.

1935 – Appointed as a council member for the Women’s Engineering Society.

1936 – Pauline is the first woman to be awarded the Air Ministry’s Second-Class Navigator’s Licence.

1 NOVEMBER 1936 – Dorothy Gower, Pauline’s mother, takes her own life. This has a profound and lasting effect on Pauline.

1938 – Publishes Women with Wings, her lively account of pre-war flying and memorable air circus summers with Dorothy Spicer. Amy Johnson, their close friend, writes the foreword.

1939 – Pauline is appointed a commissioner of the Civil Air Guard, a scheme to train a reserve of British pilots.

1 JANUARY 1940 – Pauline is authorised to form the women’s section of the ATA and recruits the First Eight pilots, to much press attention.

SUMMER 1941 – Fifty women pilots are now on board and a second all-women’s ferry pool is established at Hamble, near Southampton. Pauline moves permanently to White Waltham, the ATA headquarters.

NEW YEAR’S HONOURS 1942 – Pauline receives an MBE for her work as Commander of the Women’s Section, the first ATA member to receive such an award.

13 FEBRUARY 1942 – King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visit White Waltham.

SPRING 1942 – The first group of American women pilots, recruited by Jacqueline Cochran, travel to Liverpool to be met by Pauline and welcomed into the ATA.

MAY 1943 – Pauline is appointed to the board of the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), the first woman to hold such a position in the United Kingdom. She serves until January 1946.

2 JUNE 1945 – Pauline marries Wing Commander William Fahie at Brompton Oratory, London, with many ATA women pilots present. They move to a house in Chelsea.

SEPTEMBER 1945 – The ATA is wound down and an air pageant is staged at White Waltham. On 30 November, First Officer Audrey Sale-Barker lowers the ATA flag and the pilots disperse.

1946 – Pauline becomes pregnant but suffers from poor health throughout her pregnancy.

2 MARCH 1947 – Twins Paul and Michael are born safely but Pauline dies three hours later from heart failure. A tragic loss to family and friends, and the many women pilots she led throughout the war.

1950 – Pauline was posthumously given the Harmon Trophy Award, a green patina bronze sculpture of an aviator holding a biplane overhead with an eagle emerging from a stone.

PROLOGUE

FLYING ON AHEAD

I took several wrong turnings, as she had done many times in the sky, decades previously. Alone in her plane, who was to know? Studying her map before take-off, watching out for landmarks familiar and strange, following rivers and railway lines, occasionally putting down in the wrong airfield. Never daunted for long, flying on again, finding the right destination with a triumphant smile. A flourish of a successful landing. Her patient engineer accepted these diversions but sighed at the length of some of her Piffling Poems for Pilots. They often had time on their hands, waiting around in empty fields for paying passengers. But by then they had broken several records between them, for women in aviation in the 1930s, and had set up the first all-women joy-riding business. Days were long and arduous, but with their three-seater Spartan Helen of Troy the sky was theirs, all day, every day. Never mind the occasional mishap – landing in a swamp in a brand-new plane, with two passengers thrown into the murky waters, or having a serious near-miss on another forced landing, resulting in a cracked head and several weeks in hospital for the pilot, and some careful aircraft reconstruction for the engineer. Resilience was key.

They set up home in a caravan near their plane, saw off night prowlers – real and imagined – cooked, ate and worked side by side, thousands of flights, routes and destinations over six summers. They formed a unique and successful partnership, paving the way for women pilots and engineers in their pioneering trail. Air circus life was tough – a new town every day, another crowd to entertain with stunts, flights and more – but youth was on their side. For the most part, life was fun and full of airborne adventure. It was the life they had chosen, a job they carried out with dedication. Making a living from aviation had always been their plan.

After consulting my digital map and discarding a layer on that warm May afternoon in 2021, I found my own destination. Six years previously, on my first research trip to Pauline Gower’s home town of Tunbridge Wells in Kent, I had caught a bus to the wrong graveyard. A Victorian picture postcard church and bluebell-carpeted grounds, with helpful volunteers tending graves who pointed out Jane Austen’s brother and other local figures of note. I twice met a man walking his dog as I circled the stones; the second time he grinned and asked if I was choosing my spot. The visit led to a poem, ‘The Wrong Graveyard’, but not to the right grave. Timing was everything, as Pauline herself knew.

This time I was in the right place and almost by instinct made my way through the long grass towards the Gower memorial. An auspicious moment, as a light plane circled overhead – the only sound on the springtime air. Here lay Sir Robert Gower and his wife Lady Dorothy Gower and their younger daughter who had her own inscription, as befitted her rank and status. After several days exploring Tunbridge Wells, up and down hill, from school to library to graveyard, this was the source of the research journey, coming full circle.

Standing in front of her grave, I thought about Pauline’s many achievements and accolades, her pioneering aviation career, her talent with the written word, her loyalty to friends and family, and her strong and successful leadership of the women pilots of the ATA during the Second World War. I’d seen some of the many trees that she’d climbed as a pupil at Beechwood Sacred Heart School, reaching for the sky from a young age. I’d wandered along streets and discovered tree-lined squares that she may have explored a hundred years previously. I’d watched clouds race across a wide Kent sky and imagined her girlhood fascination with climbing up into the enticing endless blue. I’d caught her smile and ready humour, which leapt from many of her photographs as a young woman, and the character that shone through in her stories and aviation articles – her spirit of adventure and genuine enthusiasm in encouraging other women to fly.

I laid some wildflowers on Pauline Gower’s grave, for all the family, and watched as the plane circled overhead.

Maid of the Mist

Maid of the Mist, through cloud and haze

Climbing up into the blue,

Carefree I spend the happy days

Alone in the sky with you.

Maid of the Mist, your engine sings

So tuneful and sweet a song,

The silver glistens on your wings

As swiftly you speed along.

Maid of the Mist, the sky is clear

As far as the eye can see –

Up we soar, for heaven is near,

Beckoning to you and me.

Pauline Gower, Piffling Poems for Pilots

1

CLIMBING EVERY TREE, REACHING FOR THE SKY

Women are not born with wings, neither are men for that matter. Wings are won by hard work, just as proficiency is won in any profession.

Pauline Gower

Sir Robert Gower MP compiled fifty large scrapbooks during his lifetime, later donated to Tunbridge Wells Library in Kent. He pasted in everything in the press from 1918 to 1945 relating to his long-standing political career, his animal welfare concerns as chairman of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA), and his younger daughter Pauline’s pioneering, dare-devil at times, career in aviation. Three concerns close to his heart.

One librarian described him as a ‘great hoarder of ephemera’, as I soon discovered. Robert Gower also kept dinner menus, invitations, letters, photographs, political banners and the occasional significant serviette. Everything was pasted and ordered neatly by date with hand-numbered pages. Pauline’s achievements feature prominently, and the scrapbooks form a rich and valuable archive of her career. Not that Robert was always in favour of her flying, quite the opposite in fact, and his objections may well have caused Pauline to be even more determined to make her way as a joy-riding pilot from the age of 20, and not to rely on an allowance from her father. Headstrong and determined, her early choices clearly reflected her character. Yet her father’s inherent pride in her many notable and press-worthy accolades is clearly reflected in the scrapbooks. They are heavy, professionally bound books, weighted with memories that mattered. I visited Tunbridge Wells libraries twice to read through them, six years apart; the second time after several lockdowns, during which time the books had been moved between libraries and acquired heavy grey archive boxes, also neatly labelled. Second readings can often yield more.

Pauline Mary de Peauly Gower was born on 22 July 1910 at Sandown Court in Tunbridge Wells, the younger daughter of Robert and Dorothy Gower. Her older sister Dorothy was named after her mother. No son and heir appeared afterwards, which may have disappointed their father at times. It was an auspicious year for aviation pioneers: on 23 April, aviation pioneer Claude Grahame-White, who trained at Louis Blériot’s flying school, had made the first night flight; Halley’s Comet made its closest approach to earth in May; C.S. Rolls made the first roundtrip flight over the English Channel on 2 June; and, on 9 July, Walter Brookins, flying a Wright biplane over Atlantic City, New Jersey, became the first person to fly to an altitude of one mile, in fact reaching 6,175ft (1.169 miles).

In his book A Harvest of Memories, Michael Fahie describes his grandfather as ‘a vigorous man with a forceful personality’ whose influence was strongly felt by all those around him. He was driven by wealth and power to a great extent, neither of which were in his background. Robert was keen to make a name for himself, to further his passions; he did both as a long-standing Member of Parliament who was rarely out of the newspapers. Michael was only 6 when Robert died but remembers him well.

Sir Robert Vaughan Gower KCVO OBE FRGS was not born into an aristocratic family but desired high-society connections. His father, Joshua Robert, was apprenticed as a cobbler but then progressed to become a county court bailiff. Moving into property and climbing the social ladder, he was elected an alderman of the Borough of Royal Tunbridge Wells. The family prospered during his lifetime, and his eldest son seemed determined to follow suit.

Born on 10 November 1880, Robert was the eldest of six children and attended the local church school until the age of 14. He showed a natural intelligence, however, which his father did not want to waste; so he asked a local solicitor, Elvey Robb, to ‘make a lawyer of the boy’. Robb immediately spotted his potential and advanced his education to enable him to qualify as a solicitor. Robert also followed his growing interest in politics and his extended education enabled him to enter local government. In 1918, at the age of 38, he became Mayor of Tunbridge Wells and was fully involved in local activities. By 1924 Robert Gower had become Conservative Member of Parliament for Central Hackney and received a knighthood. In the general election of 1929 he was elected MP for Gillingham in Kent, a seat he retained until 1945. He was not considered a natural debater in the House of Commons, being more at ease on parliamentary committees. Robert was also a magistrate and chairman of the Tunbridge Wells Magistrates Court for many years. He was appointed Officer, Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 1919 New Year’s Honours and knighted in the Birthday Honours of the same year. His father had certainly spotted his potential and drive to succeed.

Sir Robert Gower was a prominent figure in the local and national press, wearing his many personal and political hats. All cuttings of note found their way into his fifty scrapbooks. In September 1930, he presided as alderman over a meeting to oppose the town council’s proposal – a ‘colossal blunder’ – for a new town hall and other municipal buildings to the tune of £225,000. At the 750-strong meeting at the local opera house, convened by the Tunbridge Wells Ratepayers’ League, he deemed the original council proposal ‘an act of criminal folly’ and argued that neither the financial position of the country nor the town could justify such a proposition. It was agreed that instead £100,000 would be spent on new municipal buildings for which there was an urgent need. Interestingly, visiting Tunbridge Wells post-Covid lockdown in 2021, the town hall was sitting partially empty, with council staff working from home and parts of the building available to rent.

Perhaps the most enduring and closest to his heart of all his interests was Robert Gower’s involvement as chairman of the RSPCA, which often led him to be called ‘the dogs’ MP’. For this long-standing commitment he was made Knight Companion of the Royal Victorian Order (KCVO). There were lively press reports of some particularly memorable meetings: ‘Uproar at R.S.P.C.A. Meeting. Clash Over Vivisection Question. Angry Women’s Shrieks.’ This meeting at the Hotel Victoria in London was eventually closed by Robert Gower after two-and-a-quarter hours, with only half of the business finished. It was unclear just how many women were angry, and how many were shrieking! The chairman chose to elect eight new members to the council before he got to the contentious matter of vivisection and blood sports, which likely ramped up the tension in the room. The main clash was between the moderates and those in favour of advanced opposition to blood sports. The meeting’s drama quickly escalated. Scottish author Alasdair Alpin MacGregor, a strong opponent of vivisection and cruelty to animals, accused Sir Robert Gower of ‘counselling and procuring an assault and battery by divers persons unknown’. The matter was taken to Bow Street Magistrates’ Court and had a lengthy hearing. Allegedly, when Robert had given orders for MacGregor to be turned out of the stormy meeting, he was ‘ejected with more force’ than was necessary. There was no suggestion of Gower being personally involved in the fracas. The Bow Street magistrate dismissed it all:

At each of the three hearings the proceedings were keenly followed by many fashionable attired Society women, and both for the prosecution and the defence prominent members of the R.S.P.C.A. had been called as witnesses. In dismissing the summons Mr. Graham Campbell declared that the less he said about that unfortunate case the better. Sir Robert was warmly congratulated by a host of friends who were inside and outside the court.

This was not the only case that MacGregor lost. His books were mainly about Scotland, with a typically romanticising nature that was caricatured by novelist Compton Mackenzie. His 1931 book had a short and snappy title: A Last Voyage to St. Kilda. Being the Observations and Adventures of an Egotistic Private Secretary who was alleged to have been ‘warned off’ That Island by Admiralty Officials when attempting to emulate Robinson Crusoe at the Time of Its Evacuation. MacGregor tried to prevent the distribution of a film by Michael Powell, The Edge of the World, which he claimed was based on his work, but the injunction came to nothing. Gower had spotted this weakness and used his influence to steer both the RSPCA meeting and the court proceedings, resulting in more press cuttings for his scrapbooks.

As president of the Pit Ponies’ Protection Society, another favoured animal cause, Gower campaigned strongly for the abolition of their use in the mines. In 1930, one in every six pit ponies was injured or had to be shot, with the worst cases in Yorkshire where around 7,000 ponies were employed. Those against their use lobbied for reforms in their working conditions and pressed for mechanical haulage to replace them in the pits. The Daily Herald of 6 April 1931 reported: ‘Sir Robert Gower secured 186,400 signatures to a petition he will present to Parliament for the abolition of ponies in mines.’ A month later he’d achieved 190,000 signatures, proof of his doggedness in causes that really mattered to him.

Throughout his prominent career, Robert followed his own interests. Success, or the perception of such, often evokes a mixed response, especially from rivals. One family member said:

He had a great deal of charm, was extremely clever and had a photographic memory. I suspect that he had few close friends. He was loyal to those he had. He could be ruthless to enemies. These he was not without. There was some local enmity stemming from jealousy of his success.

Robert Gower had a temper, which has been noted, but many also agreed he was kind to those who mattered to him and dedicated to the causes in which he believed. He had interests outside of politics too. Kitty Farrer, one of Pauline’s closest friends in the ATA, recalled that Robert was very good to her on her visits to Sandown Court, and encouraged her own interests in china and porcelain: ‘He was a keen collector and had a cellar full of the stuff.’ A forceful character at times then, with an eye for a delicate tea cup.

Pauline’s mother, Dorothy Susie Eleanor, was born on 19 May 1882 in Kensington, London, the only daughter of the Wills family. They were considered of higher social standing than the Gowers, so Robert had moved up in the world. They were married on 29 June 1907 at the historic Holy Rood Church in Southampton. Dorothy had ‘a warm, effusive nature and a strong developed sense of humour’. As well as being a gifted musician, Dorothy also enjoyed horse riding; twin passions that she passed on to her younger daughter. They also shared a love of writing; Dorothy published short stories, articles and a longer piece entitled A Salad of Reflections. She was prone to depression, and Pauline too suffered from dark periods throughout her life, some of them prolonged. Dorothy Gower is a rather elusive figure in Robert’s scrapbooks, there in occasional press cuttings opening a church fete or similar. Or sometimes her absence, with a headache, is noted.

Dorothy and her younger daughter were very close, and she has more prominence in Pauline’s own scrapbooks, which were later donated to the RAF Museum in Hendon, north London. In early January 1930, it was reported in the press that Lady Gower was lost overnight, her car nowhere to be found. The family had all suffered from a bout of flu; first Dorothy, then her husband and then Pauline. Between Christmas and New Year, Lady Gower had agreed to present the prizes at the Gillingham Conservative Club whist drive and dance at the town’s pavilion. Not long after leaving the family home in Tunbridge Wells, she encountered dense fog and her continued absence led her to being reported missing to the police. The Automobile Association had been actively looking for any stranded motorists that night and had found a shivering Lady Gower near Maidstone at around 11 p.m. She had of course missed the prize-giving event, so drove back to Tunbridge Wells to arrive home around 2 a.m. In a piece entitled ‘Lady Gower’s “Night Out”’, the Chatham, Rochester and Gillingham Observer concluded that ‘it seems that neither our Member nor his family have had the best of luck this Christmastide’.

Later that week, they had a better night out when Pauline and her mother were guests at the wedding of Captain Richard William Spraggett, Royal Marines, and Miss Mary Lois Cecil Power, eldest daughter of Sir John Power, Bart, MP. It was presumably a political connection through Robert Gower, with the bride acquiring a memorable married name.

Dorothy Gower must have shared some of her husband’s interests however, supporting his causes as a loyal society wife. She dutifully opened a dogs’ jamboree one summer, its poster asking: ‘Is your dog going to Chiswick?’ The event was held in ‘the beautiful grounds of Chiswick House’ and categories included ‘dog with the longest tail’, ‘the most bandy-legged dog’ and ‘the dog with the longest beg’. The programme was in two parts, presided over by Ringmaster Captain Fergus MacCunn. Luckily, Dorothy did not have to judge all categories!

In April 1930, Lady Gower stood in for her husband at a presentation to the National Association of Navy and Army Pensioners, at the Army and Navy Veterans’ Club in Gillingham. Robert Gower had sent written apologies owing to his parliamentary commitments. Coincidentally, it was another foggy day and Dorothy, accompanied by Pauline, arrived late but to a ‘rousing reception’. Lady Gower graciously presented an illuminated address to the Honorary Secretary Mr Martin Scamaton for his long-standing ‘magnificent work’ in connection with the club, while Mrs Scamaton (her Christian name was not recorded) received a China tea service. Duties done, mother and daughter were more than likely treated to tea and cake.

On another occasion, in October 1931, Lady Gower again stood in for her husband. The women’s section of Gillingham Conservative Association held a whist drive and dance, attended by both Dorothy and Pauline. Lady Gower apologised for her husband’s absence, with a general election likely due soon, but hoped that he could rely on local support of the association and that the majority could be even bigger than last time. Very much a family election campaign!

There is a photo of Pauline’s parents from 1931 in A Harvest of Memories, from the family album. They are in full country attire in the grounds of Sandown Court, Tunbridge Wells, and holding their pet dogs Kelpie and Wendy. Their younger daughter inherited their love of animals, as she often took her own small dog (also called Wendy) up in her plane. In fact, Wendy was to fly 5,000 miles with Pauline!

Pauline was born two years after her sister Dorothy Vaughan Gower. One photograph shows them aged around 3 and 5, either side of their father, in the gardens of Sandown Court. The sisters are dressed in white, ribbons in their hair, each clutching a posy of flowers and holding their father’s hand. Robert Gower has something of the look of T.S. Eliot, the customary parted hair and rather stiff expression. It is difficult to guess the occasion, or if Lady Gower was the photographer. Certainly, this was one for the family album. Thereafter their photographs are of separate women – strong characters in their own different realms. Perhaps they vied for their parents’ attention, as siblings do, but Dorothy was there for Pauline after her operation and Pauline was chief bridesmaid at her sister’s wedding.

Dorothy also appears in her father’s scrapbooks – he includes cuttings of her achievements, as he does for Pauline, although she did not make the papers to the same extent. In April 1931, Dorothy was mentioned in the Courier – ‘honoured by being appointed a Lady-in-Waiting to H.R.H. the Princess Clotilde, of Belgium. Miss Gower, who recently returned from a tour in Ceylon, is now in attendance on H.R.H.’ Robert would have been characteristically proud of the royal connections, bringing fine repute to the family name.

Later that year, Dorothy’s engagement to Mr George Hamilton Ferguson, son of the late Mr Henry T. Ferguson and Mrs Ferguson of Bovey Tracey in Devon, was announced, with the wedding due shortly afterwards. Her photograph by Gilbert Bowley, which also appeared in the Courier, was rather severe in profile, with a side parting and similar sculpted marcel wave to Pauline’s own, but perhaps with not the same twinkle playing around her eyes.

Dorothy’s wedding on 8 October was reported with enthusiasm, with mentions of both her father and sister. In the style of the time, the headlines ran ‘Sir Robert Gower’s Daughter Married’ and Dorothy’s name appeared lower down the piece. The couple married at the Roman Catholic Church of St James’s, Spanish Place, London, as ‘the sun shines through the autumn leaves’, and with Pauline in attendance as chief bridesmaid. She wore turquoise silk marocain with a matching velvet ‘coatee’ and a head-dress of pale lemon leaves mixed with blue (‘a very new combination of colour’). Hopefully the bride did not mind the papers’ focus on her sister as ‘the youngest lady aviator to hold the Air Ministry’s “B” certificate’, but Pauline was the story of the moment. The Kent Messenger included a photograph of, ‘Sir Robert Gower and Miss Pauline Gower, the noted airwoman, waiting for their car after the ceremony.’ Robert has taken off his bowler and Pauline is rather self-consciously holding a small bouquet. Neither look like they have just attended a family wedding, but they may have been caught off guard. They are unmistakably related.

Dorothy and George had three children, keeping traditional Gower family names – their eldest Robert Maule Gower Ferguson, who became a solicitor in his grandfather’s footsteps, was born in 1932, followed by Beatrice Margaret Ferguson and Sally Pauline June Ferguson.

Folded into one of the Gower scrapbooks, carefully pressed and preserved, was a celebratory serviette for wedding guests, with delicate blue flower scrolls in each corner, a central illustration of the couple emerging from the church, and the inscription ‘All Blessings and Happiness to Them’. Robert clearly wanted to remember the significance of the day. I reflected on the autumn leaves and the wedding party as I folded it back into the book, following the crease marks he had made ninety years ago.

BEECHWOOD SACRED HEART SCHOOL

Pauline Gower’s school years were central to her character, fuelling her drive and determination, and establishing her interests and future potential. Her father chose Pauline’s school with the ‘same degree of determination’ he did most things. She very much inherited this characteristic, revealed in her ability to push herself and others to achieve results, despite the challenges and obstacles along the way. She brought her ready smile to most situations, smoothing the path of resistance at just the right moment. Robert Gower’s smile does not appear so easily in his many press photographs, the formality of most occasions notwithstanding, except on one occasion when out canvassing and hoping to gain the vote from a group of women. A charming flash that quite changed his otherwise rather stern public persona. Pauline also inherited a strong political awareness and drive from her father, but clearly brought her own skills and sensitivity to issues and circumstances as required.

Robert Gower wanted both his daughters to have a solid education, unusual for the time, and chose Beechwood Sacred Heart School in Tunbridge Wells, not far from Sandown Court. He was not a Catholic but the headmistress at the time, Mother Ashton-Case, was a cousin of Lady Gower’s. The convent school was to mould Pauline’s character in many ways; Beechwood was ‘bred in her bones’ it seems, like it was in the many generations of children sent by their families. She attended first as a day girl, then a full-time boarder, despite living locally, and so the school became her whole life, and she made the most of all it had to offer. She did not take a back seat. These were on the whole happy years and, if she had felt constrained within the convent structure and stone walls at times, she found her own ways of quiet rebellion.

Beechwood was part of the innovative Society of the Sacred Heart, founded in 1800 by French post-revolutionary Madeleine Sophie Barat (born 12 December 1779), who had a vision of an influential female religious order, similar to the Jesuits, with a strong focus on teaching. She wanted to bring the nuns out from behind their symbolic grilles and encourage them to travel, teach and inspire. Women in France had almost no legal rights at that time and religious life was under threat. The society was successful – its leader meant business – and it quickly expanded into other parts of Europe, and then to North and South America, New Zealand and Australia. Sophie Barat died in 1865, by which time there was a network of eighty-nine Sacred Heart houses across seventeen countries.

In 1915, in a war-torn world, Madeleine Bodkin brought a small group of nuns to Tunbridge Wells to settle at Beechwood, a former country home. By now the society was established in England with schools in Roehampton, Hammersmith, Brighton and Carlisle. Pauline was only 5, but Robert Gower would have been aware of the debate raging over women’s education. Earlier, in 1868, the Taunton Commission had highlighted the lack of adequate private education for girls. Janet Eskine Stuart, leader of the worldwide Sacred Heart movement and long-standing superior at Roehampton, published her book The Education of Catholic Girls, which argued that men and women had different roles but that these were equal, and complementary. With such a revolutionary focus on educating girls, it was no wonder that the spirit of Beechwood, founded and rooted in the ideology of the Sacred Heart Sisters, would have such an influence on Pauline’s own life and aspirations.

A possible clash of values might have been the Sacred Heart assumption that women should focus on their roles of wife and mother above all else. Pauline was determined to follow her chosen career, once she had a taste for the sky, and may have been ready to fly, literally onwards and upwards, once out of the school gates.

A GLITTERING FIGURE

Many former pupils and peers confirmed that Pauline was a golden Beechwood girl: bright, full of fun and ready for adventure. She was a girl of action, showing early determination and a strong sense of team spirit. A keen hockey player, she was also captain of the netball team, pictured proudly holding trophies in several photographs. At 18, Pauline was part of the Tunbridge Wells Tennis Six, proving that she was indeed an athletic all-rounder.

Musically very talented, she played both violin and five-string banjo and was part of the Sacred Heart Toy Symphony Orchestra. She had inherited her mother’s love of music and embraced all else that the school offered in extra-curricular activities. She certainly did not hide in the shadows. School friend Yolande Wheatley, six years her junior and clearly awestruck, offers a glowing memory:

Successful academically, musical, very good at games, she was popular with her schoolmates and the nuns, not just because of her talents and amusing ways, but because she was even-tempered; I can’t reflect her being unfair or unkind to a junior. She could always be relied on to organise treasure hunts in the school grounds, charades or surprise concerts, and her singing Lancashire songs accompanying herself on the ukulele, its ribbons flying as she danced around, is still a jolly memory.