2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Riva

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Tricky maneuvers, curious passengers, and other kinds of turbulence The star DJ who spontaneously invites the entire flight crew to his concert in Rome, the businessman who has his forgotten cigars flown in by private jet, and the oil millionaire who has the stewardesses crawl through the cabin on all fours to the sound of Pavarotti arias—there's nothing that Pilot Patrick has not experienced in his job. Germany's most famous airline captain takes us on a joyride to the most beautiful places in the world, telling us how he made his dream of flying come true, what really helps against the fear of flying, and what you should consider if you want to become a pilot yourself. From wild party nights on the Côte d?Azur to sex above the clouds, Pilot Patrick gives us an exclusive look behind the normally closed doors of the international jet set—and reveals a secret that, until now, has always flown below the radar.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 268

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

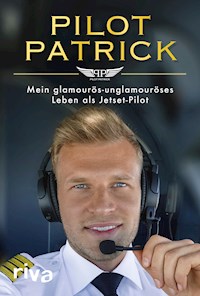

Patrick Biedenkapp

PILOT PATRICK

Patrick Biedenkapp

PILOT PATRICK

My glamorously unglamorous life as a jet-set pilot

Bibliographical information from the German National Library:

The German National Library (Deutsche Nationalbibliothek) has recorded this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie [electronic resource]. Detailed bibliographical information can be found online at http://d-nb.de.

All the stories told in this book are true, but, for privacy reasons, the names of some people and companies have been replaced by pseudonyms, and places and other characteristics have also been changed.

The pictures are from the author’s private archive.

For questions or suggestions:

1. edition 2020

© 2020 by riva Verlag, an imprint of Muenchner Verlagsgruppe GmbH

Nymphenburger Straße 86

D-80636 Munich

Tel.: 089 651285-0

Fax: 089 652096

Published in Germany in 2020 by riva Verlag, an imprint of Muenchner Verlagsgruppe GmbH, Munich, Germany, as Pilot Patrick. Mein glamourös-unglamouröses Leben als Jetset-Pilot by Patrick Biedenkapp.

All rights reserved.

All rights reserved, especially the right to reproduction, circulation and translation. No part of the work may be reproduced or stored, processed, copied or circulated electronically in any form (photocopy, microfilm or other method) without the publisher’s written consent.

With the collaboration of: Peter Peschke

Translation: Emily Plank

Proofreading: Sylvia Goulding, Diana Vowles

Type-setting: bookwise GmbH, Munich

Cover Design: Marc-Torben Fischer

eBook: ePubMATIC.com

ISBN Print 978-3-7423-1723-0

ISBN E-Book (PDF) 978-3-7453-1410-6

ISBN E-Book (EPUB, Mobi) 978-3-7453-1411-3

For more information on the publisher, visit:

www.rivaverlag.de

Please also read about our other publishing houses at www.m-vg.de

CONTENT

CHAPTER 1 – Glamour for one, please—a totally “normal” first day of work

Short superstars and mountains of meatballs

CHAPTER 2 – A roller-coaster designer and other magical career aspirations

A little crash-landing before takeoff: Finding a flight school

From ATC to WTF?!: Some initial theory and pilot jargon

Have fun . . . and “happy landings”: My first flight

The plane is refueled, but not the pilot: Flying lessons in Zadar

It’s always wise to study: The first exams

The first tragedy of my young flying career

A rocket launch in a pensioner paradise: My IFR flight training in Florida

Ten tips for aspiring pilots

Back to Zadar: The third and final practical phase

Trial session in the simulator

CHAPTER 3 – Minimum five years’ experience, new graduates welcome: The job search

Ten tips for your application

Wheels up for a new life

The no-hassle package: Let us take care of it

Europe’s finest airports

The second tragedy and the old chestnut of air safety

CHAPTER 4 – We don’t expect any turbulence; please hold on to your wallets

Zero percent pleasure in the Blow Up Hall

Go right back, I forgot something

Olbia’s catering mafia

Healing water and ALDI yoghurt

Empty tank, full client

Please, wait!

Shady characters

Stewardesses and mistresses

We don’t need a cleaner; we’ve got a pilot

No dessert for me, thanks

Always working, but not always fit for it

What we expect from you: Look good

Cowboys above the clouds

Flying under the radar—but why?

Goodbye Berlin

CHAPTER 5 – Hello Hamburg: New company, old problems

Female pilots and male flight attendants

FAQ: What do you pilots actually do?

. . . if you would please excuse me, Mr. Gorbachev

Social media: Where reach isn’t measured in tankfuls

There’s work, there’s pleasure—and there’s Instagram

Spectacular aerobatics

No photos, please!

CHAPTER 6 – Going up a size

Private jets or commercial airliners? Both have their advantages

Switching to the left-hand seat, or: My rise to captain

Captain’s training

Forever on solid ground? Coronavirus (COVID-19) and its consequences for the aviation industry

CHAPTER 7 – Listen, baby!

What to pack in your carry-on luggage

What to pack in your checked luggage

Additional packing tips

Ten tips to combat your fear of flying

About the author

CHAPTER 1

GLAMOUR FOR ONE, PLEASE—A TOTALLY “NORMAL” FIRST DAY OF WORK

I had certainly imagined the whole glamour thing to be very different.

Pilot for a private jet airline—it was a job that promised new adventures every single day. Insights into the life of the rich and the beautiful, of the stars and starlets: Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie, Tom Ford or Karl Lagerfeld would have me fly them to Nice, London, or Paris. New encounters with the jet set every single day, a veritable Who’s Who of society—and even if I were just their pilot, it would definitely be exciting and always new. This, roughly, is how I imagined my first job after completing the training.

Beautiful, high-quality things have always had an almost magical appeal to me, and in private aviation, that much was certain, I would meet the people who could afford such things. Because if you have sufficient cash to hire a plane and jet from one continent to another, for a weekend of shopping, glamour will also find its place in your life in other ways. The less varied humdrum work at one of the many scheduled flight providers was rather less appealing to me at the time. Instead, I preferred to fly “the celebrities” while getting a little taste of their world. It would somehow be very sexy, that first job of mine, I was sure of that.

So, my first duty was . . . pretty sobering. It had been a few weeks since I had signed my employment contract with a Berlin-based private aviation company. That’s when the waiting game started—initially, waiting to finally have my license issued by the relevant authority. Then, having received this, waiting to be included in the new roster. Finally—unexpected and all of a sudden—the day arrived, at long last. I was woken by a call on my cell phone at 6:30 a.m.; a first officer had gone sick and an immediate replacement needed to be found. How soon could I get to the airport? I decided to wing it. With little planning or organization, I threw whatever I could lay my hands on into my suitcase. I hadn’t been told how long I would be away, so I didn’t know what I was going to need. I quickly ironed my uniform—only to spend the whole trip to the airport trying to remember if I had turned the iron off. I’m sure that’s a worry many people have in those kinds of moments. It’s baseless, of course—it’s just that we have too much time to think about it. And that doesn’t necessarily change once you’re onboard the plane. But this time, I would be in the cockpit, so would soon be otherwise occupied. (My house was still standing when I got back; I had turned the iron off.)

I met the rest of the crew at the General Aviation Terminal (GAT) of Berlin Schönefeld airport. There were three of us: the captain, a Polish stewardess, and me. I had seen the stewardess maneuvering a fully loaded discount store shopping cart along the tarmac on my way to the plane. She had obviously been tasked to procure drinks and other stuff for the flight. Yet, despite the champagne bottles I spotted in the cart, there wasn’t a whole lot of glamour going on. Even the hangar outside which the plane was parked looked pretty cheerless, though the aircraft itself, a Cessna Citation XLS, was worth well over US$11 million.

The captain seemed like the kind of guy who believed jumping in the deep end was the best way to learn how to swim: He cut straight to the chase to explain PF (“pilot flying”) to me. As you might expect, this term means that I would be the one controlling the plane while he monitored. I knew this would be part of my “line training,” where you learn all the specific flight operation procedures, but was nevertheless quite surprised to discover it would be happening on my very first flight. The captain would of course instruct and assist me where necessary, as he was aware it was my first duty for the company. But it was still all a little unexpected, and felt like a giant leap of faith. I was both proud and nervous.

We would be flying from Berlin to Zurich—initially without passengers, as per the plan. This made the “stage fright” a little more bearable. I did, of course, know what I had to do once I took my seat on the right-hand side of the cockpit. I had practiced the procedures over and over again during my training. But it was still all unfamiliar to me. I wasn’t sitting in the good ol’ flight simulator, where, if in doubt, I could just press “Pause.” It wasn’t a case of going through the correct emergency procedures as we usually did in training. It was a regular flight from A to B, which was something I had so far—if ever—only practiced without any passengers or crew. Plus, we were late; our VIP client would soon be landing in Zurich, which was now our destination. Private aviation is not an industry where providers can afford to be tardy. In short: It was time to put my skills to the test. There was no room for error, and I was suitably tense. But I was managing okay in the cockpit. All the checks went to plan, and the plane responded to my actions and commands. Finally, ladies and gentlemen, we reached our scheduled altitude and set off toward Zurich.

Short superstars and mountains of meatballs

Once at Zurich airport, we prepared the plane for our actual flight order. Abundant catering was ready and waiting at the GAT. But our client, a rich Polish woman—or should I say: the daughter of a very rich Pole—, kept us waiting. Oh well; at least I got to have my first celeb sighting: A lady with a long blonde mane, climbing rather awkwardly out of another private plane, turned out to be Colombian pop star Shakira. “Can she not walk?” I wondered. At first glance, you could have been forgiven for thinking she wasn’t totally sober, given the way she staggered across the tarmac to the terminal. But, looking a little closer, I saw that her main problem was most probably the giant platforms affixed to the bottom of her shoes (which easily elevated her above the 5’6” mark, even though she’s really only 5’1”). Shakira may not quite have been up with the latest shoe fashion, but still: It was thanks to her that I got a brief glimpse of a world-famous star on my first day of work. I was also shocked at the piles of luggage she was traveling with; a seemingly endless trail of suitcases and bags was being hauled out behind her. The plane was also a Cessna Citation XLS, so I was able to get an idea of what I could expect in future—because loading and unloading luggage was the crew’s job.

We were ready for our onward flight to Warsaw. The only person missing was our client. Along with the captain and stewardess, I waited for the lady who would be providing me with my first glamorous assignment. The catering alone looked promising. It would have been enough for the entire crew. Mountains of attractive appetizers, including meatballs. Plus, canapés, a selection of salads, and a whole bunch of fruit cut into mini works of art. All for just one person and a 90-minute flight. I had to restrain myself from grabbing some. The champagne, which had also been carted onboard in crates, was of course already a no-go for us.

Finally, a call came from OPS (“Flight Operations”): The flight had been canceled for that day. While I was the one on my first duty, it was the client who had committed the rookie mistake that resulted in the cancelation: When booking her connecting flight from Zurich, she had done so for the same day as her flight from New York—without taking into account the fact that this first flight was an overnight one lasting more than eight hours. So, the connecting flight wouldn’t be happening until the following day. She had booked us twenty-four hours early. While we were waiting here, she was probably still supervising the staff in her New York penthouse, making sure they were packing her bags correctly. (As everyone knows, rich people always live in penthouses and have their bags packed for them. In reality, I actually have no clue what Madam’s living arrangements were.)

The 6:30 a.m. phone call, the panicked bag-packing and unnecessarily hasty dash, the flight to Zurich—it had all been for nothing. I then had someone ask me, in all seriousness, if I could help dispose of the catering. I’m always happy to help, but what did they mean by dispose of? Were all the expensive canapés just going to be thrown in the trash? They certainly weren’t going to be served up again the next day, I was told, and unless I wanted to eat them all myself, I should quit questioning, get to work, and start throwing them all out so we could finally head to the hotel.

And get to work I did. Thank goodness for throwing out all the good food. Like most of us, I was raised in a family where throwing out food was rightly frowned upon. I asked the captain for permission, then set about helping myself to the catering. I sat in the plane’s comfortable cabin—a pleasure for which our clients pay around US$4,500 an hour. I was just twenty-two years old, so my metabolism was in great shape. But it was still an ambitious undertaking, and neither of my coworkers was prepared to help out. They had seen all this luxury catering stuff before, and simply weren’t interested. What I couldn’t eat there and then, I mostly packed in plastic bags and took back with me to the hotel, where I later scarfed down more meatballs until I couldn’t for the life of me fit in another mouthful. I hadn’t flown any passengers, but there I was, sitting in my hotel room with a belly full of posh catering. I actually felt quite ill from all the food, and the whole episode didn’t ultimately strike me as particularly glamorous. Our accommodation was super comfortable, though.

So, there you have it; my first day in a career I had imagined to be so glamorous: a hasty departure, an empty-leg flight, a canceled flight, and a solo assault on the cold buffet. As I said, I had envisaged it differently. At twenty-two, you not only have a strong metabolism; you also have dreams. Over the coming weeks and months, I would learn what my coworkers meant when they said, “you might be sitting at the front in the cockpit, but it’s the ones behind you who’ve really made it.” Because, of course, we were simply the staff of the established upper-class and the nouveau riche, of politicians, rock stars, and Hollywood actors who didn’t think twice about ordering a plane to spend a weekend in the Mediterranean. We were like spectators of this glamorous lifestyle, doing work, and collecting a plethora of anecdotes along the way. Oh, and meatballs—did I mention those?

CHAPTER 2

A ROLLER-COASTER DESIGNER AND OTHER MAGICAL CAREER ASPIRATIONS

There are some professions where people constantly ask you how you ended up there. Milliners and foot surgeons, for instance. Jobs people tend to hear little about, and which don’t necessarily figure in career-orientation programs. When it comes to pilots, however, most people assume you’ve been dreaming of flying since the age of four. It’s one of those classic “dream jobs” little kids have, and many of my coworkers certainly did know what they wanted to do before they were even old enough to read and write.

My first career aspiration was to be a magician. I wanted to amaze people and blow their minds—and I definitely believed many of the tricks being performed at the time were the work of magic. My childhood idol was David Copperfield, who was such a prominent figure in the early ’90s that he could afford feature-length shows on Germany’s popular RTL television channel— genuine extravaganzas that would see him make entire trains disappear. What most impressed me, however, was a trick in which the master magician flew over the stage. Without any visible aids, he lifted off—just like that—, flew into glass boxes, and carried attractive young women up into the air in his arms. As a young boy in Frankfurt, I even had the opportunity to attend one of his live shows, and it was this particular routine that had a huge impact on me. It would be only a few years until the magician market was claimed by a bespectacled wise guy named Harry Potter. But I would probably have been a Ravenclaw at Hogwarts, or maybe even a Hufflepuff. And that doesn’t really involve taking the lead; you’re instead stuck in a completely insignificant support role for seven books and eight films. (Let’s face it: Flying on a broomstick is not exactly something you’d classify as glamorous, even if it is a Nimbus 2000. Not at a school named after skin growths on a pig butt.) So, my dream of becoming a magician eventually faded from the spotlight.

Back then, I wanted to do something creative in general. I wanted to let my artistic flair run wild. Later, my ideas for a professional career would center more on the talents and preferences that would actually earn me money on the job market. Like nearly everyone in my family, I had always been quite technically gifted and good with my hands. My father renovated and extended our house virtually on his own, while my grandpa was forever tinkering away at cars and motorbikes. Young Patrick was a constant presence, watching over the adults’ shoulders and pitching in whenever he could. That was very inspiring for me. I decided I wanted to design roller coasters or cars. Probably airplanes too. After all, someone had to do it, right? I was incessantly drawing little diagrams to immortalize my ideas. This turned out to be an ideal way to combine my technical affinity and my creative streak. But when, a few years later, it came to thinking about how I could turn this hobby into a career, the prospects were pretty dismal and daunting. While I may not have lacked the necessary technical understanding, I was not one for prolonged, theory-based study peppered with numerous stints of work experience. I had always been more of a doer, and I wanted to see and experience the products of my work directly. People who design cars and planes spend a lifetime at the drawing board, often not even being able to savor the fruits of their labor at the end of it all.

I have loved airplanes since early childhood, and had spent many a weekend at the airfields around Frankfurt with my family. We lived in a small town nearby, and there were often air shows or similar events that gave me the opportunity to see daredevil pilots getting into light aircraft and performing bold, gutsy maneuvers. We kids—my brother and I, and all the others—were absolutely mesmerized. Many of us naturally tried to imagine what it would be like to sit in the cockpit and dash through the clouds. I was fascinated but also sad, because I wasn’t the one flying the planes.

It was my father who, years later, gave me the idea of training to be a pilot, which had been his dream job. His career ended up taking him in a different direction, and he today works in finance and software. But his simple, probably quite spontaneous suggestion of “Why not get your pilot’s license?” resonated with something inside me. I was eighteen, and had almost finished my final school exams, so it was time to start making some concrete plans for the future. My father was pretty much preaching to the converted. It soon became clear that flying would be a good fit for me, and was something I’d like to try. So, I started researching into what pilot training involved, what the prerequisites were, etc. It’s worth mentioning here that this “training” was not part of the usual apprenticeship process followed in Germany for “state-certified industrial trades.” Instead of completing the standard three-year, part study / part practical apprenticeship, it is sometimes possible—depending on the type of training—to obtain a commercial pilot’s license in just eighteen months. (The term “obtain” is itself used rather loosely here, given that it’s naturally not something you can just go out and buy. But more on the specific requirements later . . .)

A little crash-landing before takeoff: Finding a flight school

Anyone looking for information on pilot training in 2006 would inevitably find themselves inquiring with Lufthansa, which offered a financed program. This ran for around twenty-four months, and taught you the skills needed to basically fly anything from a hobby plane to an Airbus (with additional training required for the larger aircraft). To qualify for the free training, you had to sit a comprehensive recruitment test. I might only just have started my compulsory civil service at a kindergarten, but what did I have to lose? I registered for the recruitment test, which was to be held at the DLR, the German Aerospace Center, in Hamburg.

I knew very few of the candidates applying for the pilot training would have prior knowledge, but I’ve always been a determined person who never shied away from extra work or effort, so when I set my mind on something, I manically learn everything I can. I bought software (at the time still on CD-ROM) that had been developed specially for would-be pilots. Memory training, complex mental arithmetic and math, reactivity, personality tests; I crammed like no tomorrow. The recruitment test would be held over two days, and when I finally headed off to Hamburg, I was as well prepared as I could possibly be . . .

. . . only to crash-land on the very first exam. It wasn’t for lack of preparation; it was a classic case of exam nerves. I was suddenly distracted by this cheerless room, which was filled with forty candidates who didn’t know each other. Unfamiliar faces everywhere, each one of us seemingly hell-bent on prevailing over the others, no matter what. Coupled with this was the stuffy air, the cold fluorescent lighting, and a tense vibe that spread like a virus—and, all of a sudden, I was no longer able to focus on the task at hand. We had to memorize sequences of letters that were shown briefly, and then write them down. I created mnemonics by concocting matching phrases. For example, if the sequence was “HPBTAOFJ,” I tried to memorize something like “Harry prays before the altar of Father John.” I suspect this only made me more confused, as it wasn’t a method I had practiced before. It also had to be done superfast, while the sequences got longer and longer, and I was overcome by nerves. I failed that section so spectacularly that I wasn’t able to make up for it in the other sections where I did much better.

It came as little surprise when, soon after, I found out I had flunked the recruitment test. My unexpected exam nerves and those damn letter sequences had brought my dream to an abrupt end. I was totally shattered, and had no idea what to do next. Over the previous few weeks, I had devoted all my energy to the exam preparation. For months, the idea of becoming a pilot had been my motivating force. And now? Nothing.

A friend finally alerted me to the fact that a flying school in Frankfurt—a subsidiary of Lufthansa—was running a private training course. At the time, the school was trading under the name of InterCockpit; today, it is part of the European Flight Academy (EFA), which spans the Lufthansa Group flying schools in Germany, Switzerland, and the USA. The whole thing had a similar structure to the training I had unsuccessfully applied for, except that it would be held in different places— and trainees would not receive any funding; they had to finance everything themselves. The total costs amounted to more than 70,000 euros (about US$80,000). I weighed up my options. I asked people who were currently undertaking the training to find out if it would be my thing too. (Unfortunately, there was no social media at the time, and consequently no Instagram account of a young pilot providing detailed work updates for his followers . . .)

The information I managed to glean from my mini interviews left me with a really positive feeling. While it was a full-time course, there was a chance I might even be able to do some part-time work on the side. Plus, I would be able to live at home—at least for the units held in Frankfurt—and thus save a lot of money. In any case, I was in no doubt I really wanted to be a pilot. The failed exam hadn’t put me off at all. I knew I had just let the whole occasion get to me.

Nevertheless—and this seemed to be the biggest problem of all—I was still far from being able to scratch up the necessary money. My parents were pretty pragmatic about it: If I had gone to college, I would not have been able to obtain any education grants, and would instead have been dependent on their financial support. A six-year (or more) course would have cost them a considerable sum, which would probably have ended up similar to the costs for pilot training. So why not invest the money in this course? We weren’t a wealthy family—70,000 euros was a really large amount for my parents. At the same time, I realize other families simply wouldn’t have been able to afford it at all. So, I was ultimately in a pretty privileged position, and I am grateful for that. It enabled me to get an early start in an established training course for a career that would provide me with a relatively secure future.

I submitted my application, and once again began preparing for the qualification test that was, of course, also required here. It particularly tested my knowledge of math, physics, and English. This time it went well; I passed the tests without any problem. (For purely financial reasons, the flying school was no doubt keen for the courses to be well attended; that said, nothing was handed to us on a platter.) I also had to undergo a medical check—a “Class 1 medical”— in Stuttgart with a specialist physician. But, as was to be expected for an athletic young man, there were no medical grounds preventing me from following my intended career path. InterCockpit also gave me the all-clear soon after. The fact I was able to provide proof of having been accepted into a training course in turn meant I was allowed to finish my compulsory civil service earlier than planned. Otherwise the final weeks at the kindergarten would have clashed with the start of my training, and I would have had to wait an entire year for the next course. So, after the initial failure to launch, everything was finally going swimmingly for me.

Incidentally, I still, to this day, have a fractious relationship with Hamburg, where I so spectacularly failed my first exam. Yes, I know it wasn’t the wildly popular Hanseatic city that had conspired against me that day. It’s not Hamburg’s fault that I was totally incapable of memorizing a sequence of letters while under stress in a large, stuffy room. So, I’d like to take this opportunity to give a particularly big shout-out to all my readers from Hamburg—it’s nothing against you, guys. But I don’t think Hamburg and I will be besties any time soon . . .

From ATC to WTF?!: Some initial theory and pilot jargon

It was in April 2008, about a month before my twentieth birthday, that I began my training that would eventually secure me a “frozen ATPL.” “ATPL” stands for “Airline Transport Pilot License,” and it would be “frozen,” because the license only becomes a fully valid ATPL once you’ve recorded enough hours of flying. Fifteen hundred, to be precise. So, it was going to take a while. Until then, the “frozen” ATPL would be my CPL (Commercial Pilot License). (I know qualified pilots who never totally understood the difference between “frozen ATPL,” “CPL,” and “ATPL.” It’s complicated.)

Of the twenty-one trainees (only one of whom was female), I was the second youngest. I had already managed to find my first friend in Fabian, whom I had met during the medical check in Stuttgart. But I was still very nervous. To feel anything else would probably have been foolish anyway; after all, I was starting a completely new stage of life. And though I initially continued to live with my parents, those first few days at InterCockpit were like my first steps into adulthood. I’m sure we all remember our first day of an apprenticeship or college. It’s that mix of confidence and fear, of grand plans and self-doubt, that engraves such days in our memory.

First there was the compulsory orientation, during which our fellow trainees, the teaching staff, and the academy itself were introduced to us. We were then provided with our course materials: About ten thick, bulging folders that, collectively, looked like an almost insurmountable pile of work. While I of course wouldn’t let myself be discouraged by this, I also made sure I was under no illusions: The next eighteen months were going to require real, uncompromising dedication. Airy-fairy attitudes weren’t going to get any of us anywhere. We were each also given a typical, black pilot’s case to help us lug the folders to class each day. (At the time I was really proud of it, but today it lies unused in my basement. Traveling as much as I do, I tend to steer clear of any luggage item that doesn’t have four wheels on the bottom and a handle on top.)

In a number of disciplines, learning by doing quickly leads to demonstrable success. For example, many people get their first taste of driving a car in an empty parking lot, as friends or parents explain to them how the brakes, accelerator, and clutch work. Then they try it all out themselves to see how they go. For obvious reasons, that would be a very bad idea in a plane. Pilot training, of course, doesn’t start with you getting straight into the cockpit to do a few trial laps. (Though, I must admit, it’s a nice idea. In general, with training that costs as much as this does, it would be good to somehow be able to get an idea of it to see if you’ve chosen the right career. If any of the fine people at the EFA are listening: Trainees should at least be given a few free hours in the flight simulator.)

So, we first had two months of theory ahead of us, teaching us what we needed to know to get a PPL or Private Pilot License. We also learned the necessary terms (and functions) for the radiotelephone operator license, without which the dream of getting your pilot license can never come true. The General Radiotelephone Operator License (GROL) enables private and commercial pilots to communicate with air traffic control, ATC for short. This required the aforementioned English skills. Radio contacts in German are permitted for flights within German airspace, but on international flights, all communication must be in English. It’s the only way to guarantee that the cockpit and control tower can successfully communicate with one another in the event of an emergency. So, to recap: The GROL enables you to communicate with ATC (which is part of the DFS, Deutsche Flugsicherung, the company in charge of air traffic control in Germany) for both the ATPL and the PPL. I was gradually starting to see why we had been tortured with those letter sequences in Hamburg; sometimes you’d see them and just think “WTF??” Fortunately, I was now much better at memorizing all the abbreviations.

After two months of theory, we were finally able to start the first practical component of the training in June. We would actually be flying. First in a simulator, so on the ground, but then in a real plane. There’s the “10,000-hours rule,” which is, ultimately, just another way of saying “practice makes perfect.” To become a master in any discipline, you need to practice, practice, practice for 10,000 long hours. The more often you perform certain actions, the more ingrained they become, until, at some point, you can do them in your sleep, as it were. While 10,000 hours of practice would, of course, have well exceeded the scope of the training, what we had been doing so far had indeed been simply practicing, practicing, practicing. This gradually gave rise to a feeling of unease, because we all knew it would soon be time to put our learning to the test.