Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

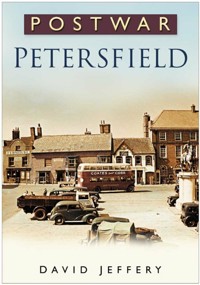

Before the Second World War, Petersfield was a small Hampshire market town of around four thousand inhabitants. During the 1950s, '60s and '70s, however, its population began to expand quite rapidly, and major architectural changes took place. This book traces this transformation of the postwar years with reference to the political decisions.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 369

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

POSTWAR

PETERSFIELD

DAVID JEFFERY

Cycle Speedway at Kimber’s Field, 1950. (Author’s Collection)

Title page picture: The Square, 1950s.

(The Petersfield Society)

First published in the United Kingdom in 2006 by Sutton Publishing Limited

The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved © David Jeffery, 2006, 2013

The right of David Jeffery to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5434 1

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Foreword & Acknowledgements

1.Austerity: 1945–52

2.Recovery: 1953–9

3.Demolition: 1960–5

4.Modernisation: 1966–73

5.Reorganisation: 1974–8

6.Consolidation: 1979–84

7.Reinvigoration: 1985–9

8.Acceleration: 1990–5

9.Prosperity: 1996 Onwards

Appendix: Petersfield Urban District Council Chairmen and Town Mayors since 1945

Contributors

Bibliography

Dog Alley, c. 1950. (The Petersfield Society)

Foreword & Acknowledgements

History is an elusive concept: a written or oral record of events is no guide to its authenticity and, even after the lapse of time (perhaps especially after the lapse of time), there is no guarantee that that original record is either accurate, non-tendentious or definitive. Whose perception of events are we relying on? What conditions prevailed at the time of recording those events? What role does nostalgia play in the reminiscence of those events? When historians attempt to define a ‘Zeitgeist’, this could be no more than a new perception of events, tainted by new prejudices engendered by subsequent ‘history’. One solution to such dilemmas facing the recorder of events is to ignore them all and simply allow history to write itself (which it manifestly does!), then to comment upon it. However, at this point, other dangers lurk: what is the role of the observer-interpreter and how is his perception coloured by his own, possibly prejudiced, stance?

We can, of course, dismiss all this philosophical conjecture and rely entirely on ‘face-value’ history, or ‘take-it-for-granted’ history, the sum of which is more like a ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ account. It may not be ideal but, like a theatre director who encourages his actors to inject their own interpretation of a script, the historian-director can at least offer his reader the opportunity to interpret events for himself. What has to be accepted, however, is the uncontrollable nature of those events. History doesn’t just happen, it lurches along in fits and starts, short bursts of civic or individual energy being punctuated by longer bouts of inertia, moments of elation alternating with periods of frustration. One family’s achievements and advances are matched by another’s setbacks and reversals. History abounds with ‘hiccups’ punctuating the flow of time and events, deceiving the optimist and slowing the pace of progress; momentum is relative. Local development has its own momentum and does not necessarily (indeed, rarely does it) correlate with the national.

The role of chance, the interaction between people and events, the catalyst of exterior forces, the intervention of government, the arbitrariness of decision-making, prevarication and delay, all play their part in forming the continuum of history and they have all performed a function in Petersfield’s development. It is this inconstancy which I have tried to portray in my account of events. Petersfield has, by chance or design, pursued a policy of gradualism in its affairs in the postwar years, and this in itself has contributed to the overall character of our town. The impartial observer probably does not exist, but, since I am not a native of Petersfield myself, I hope at least to have been objective in my judgements and to have gained from the benefit or, more presumptuously, from the wisdom of distance – and thereby to have portrayed the town I have come to love as comprehensively and as dispassionately as possible in the pages that follow.

Pre-war Petersfield was, naturally, a different Petersfield. Commentators have described it as ‘one of England’s prettiest villages’ with a quality of sleepiness, ‘dozing tranquilly’ between bouts of fervour on market days. The population was sufficiently small for most of its inhabitants to recognise, if not know, almost all their fellow townsfolk. The immediate postwar ambience was not too dissimilar: the physical environment was unchanged, the town having suffered virtually no damage in the war; the shops were those of pre-war days and remained in the hands of the same owners; families continued to make their own entertainment, unfettered by the universal availability of television or cars.

But, slowly, austerity has given way to prosperity, and that has changed everything. The first aim of this book has been to illustrate and interpret those changes that have taken place in the town over the second half of the twentieth century. However, since historical happenings do not adhere to convenient time periods, nor follow any logical pattern, references have been made to wider events, external forces at work on the community or a general appreciation of matters of national or international relevance.

The bulk of the material has been gleaned from the local press, which, while not perfect from the point of view of accuracy or historical authenticity, does provide a framework for comment and interpretation. Anecdotal material from individual interviews has been added to the core text with the aim of substantiating the press reports and to personalise the account. In addition, some historical detail has occasionally been added to give background substance and to place the events within the context of the overall story of Petersfield since the Second World War. Since ‘living memory’ accounts are such a valuable and indispensable commodity to the oral historian, I have concluded each chapter with a section dedicated to ‘Departures’, which, in their own way, indicate breaks with the past, while the ‘Plus ça change . . .’ tailpieces are there to remind the complacent that we can neither decide the pace of history nor expect too much from it.

I am indebted to a very large number of people for their contributions to my efforts: to the staff of Petersfield Library, to my colleagues at Petersfield Museum and to the undermentioned contributors and correspondents, all of whom have shared with me my fascination for the development of our wonderful town. I apologise for any inadvertent omissions or unintentional errors and, finally, thank my daughter, Anna-Louise, for reading the manuscript and making many helpful suggestions.

David Jeffery

CHAPTER ONE

Austerity

1945–52

VE DAY AND VJ DAY

As the seven members of Emanuel School’s Windsor Rhythm Kings Jazz Band spontaneously clambered on top of the air-raid shelter in front of St Peter’s Church on the evening of VE (Victory in Europe) Day, 8 May 1945, to play to the joyful crowds which were gathering around them, little did they realise that they were not only celebrating the end of six years of conflict in Europe, but also heralding the imminent emergence of a new Petersfield. The Emanuel boys formed part of a contingent of more than a thousand schoolchildren who had found themselves evacuated to Petersfield during the war years and who were shortly to leave the town that summer, thus reducing the town to its ‘normal’ size of about 5,000 inhabitants. The population of the town, which had taken a century to double in size since the 1840s, was about to treble in size in the next half-century.

On the day after VE Day, the front page of the normal Wednesday edition of the Hants and Sussex News carried a mundane report of the proceedings of the Petersfield UDC (Urban District Council), including information on respirators (gas masks) and hackney carriage licences; a warning about the local gas supply; and a short condemnation of the misuse of the children’s swings on the Heath. A mere two column inches on page three were devoted to a bland acknowledgement of the end of the war in Europe. Lack of rapid technology in the news media had made it impossible, until the following week, to mention that ‘the two days officially set apart for the purpose [of celebrating] were days of great joy and relaxation, the weather being for the most part favourable and pleasant, and in town and country alike, people generally kept holiday and were strengthened and refreshed for the great and continued effort which still lies ahead before world peace can be secured’. In the week following VE Day, the Petersfield (ex-services) Fund organised a programme of dances, a whist drive, a celebrity concert, a boxing tournament and an Empire Day Ball. There were also thanksgiving services in all the local churches.

Three months later, VJ (Victory over Japan) Day passed by relatively quietly, partly because the weather on the evening of 15 August had been too cold to attract people to dance in the open air; instead, the town hall was the venue for public dancing. The children of Petersfield had their own special jollification to celebrate VJ Day in September: the UDC arranged a party for more than 550 youngsters at the town hall, with music, tea, community singing and conjuring and Punch and Judy shows.

In 1946, the Clerk of the UDC announced that food gifts from the colonies were still being received in Petersfield: ‘150 tins of marmalade and grapefruit, a gift from the people of South Africa, have been distributed to 75 necessitous persons.’ In June that year there were celebrations to commemorate the first anniversary of the end of the war, with a cinema show at the Savoy, a fancy-dress parade, children’s sports and a Punch and Judy show, dancing and community singing, and a tug-of-war and boxing displays.

Petersfield population 1801–2001. (David Brooks)

NATIONAL AND LOCAL POLITICS

With the celebrations over, the task of conducting the 1945 general election preoccupied certain sections of the community, despite there being, according to the press, ‘not much evidence of public excitement’. Polling Day was 5 July and, of the three candidates standing in Petersfield, it was General Sir George Jeffreys, the Conservative MP for the town since 1941, who won with a lead of more than 12,000 votes over his Liberal and Labour rivals. Shortly afterwards, he announced that he would not be standing in the next election and the Hon. Peter Legh was adopted as the prospective Conservative candidate; he was elected in October 1951 with a majority of more than 14,000 votes over his opponents.

Local political interest centred around the immediate needs of the population, especially those of returning servicemen. There were calls for a maternity ward and an operating theatre at Petersfield Cottage Hospital and dedicated beds for patients recovering from illness or injuries sustained during war service. As elsewhere in Britain, there were vociferous demands for houses to be built urgently; for the moment, the projects suggested by the Advisory Committee of the Memorial Fund to provide public baths or a library for the town were rejected as of secondary importance.

Remnants of war – there had been very little material damage to the town in the war – included some Nissen huts on the Heath and air-raid shelters which were removed early in 1946. Some buildings used in wartime – Steep House, used by French Resistance workers as a safe haven, and Heath House, used as a sanatorium for evacuees since 1939 – were closed. The old library room at the town hall, given up at the outset of war to house the ARP office, now became the offices of the Surveyor’s Department of the UDC because of their increased workload. The library had had temporary premises at the (Working) Men’s Club in Station Road, but Harry Roberts, the ex-London doctor now living in Froxfield and supporting various Petersfield enterprises, suggested building a third storey on top of the town hall to accommodate the library and a reading room. His intellectual impetus was, as ever, matched by his financial generosity and he offered the first £100 towards this project ‘to start the ball rolling’. Lord Horder, who lived at Ashford Chace, later contributed a further £100 to the scheme. Harry Roberts’ concern for the town’s future was expressed in a letter to the Hants and Sussex News.

Petersfield’s steady drift into a suburban status, which has lately begun and threatens to advance, is lamented by all who care for individuality, character, distinction and beauty. The normal population of Petersfield is rather too small for a vigorous market town possessing, as it should do, its theatre, art gallery and the rest; and one or two light industries, such as printing, bookbinding, furniture making, would go well to supplement the rural educational potentialities.

THE EDUCATION DEBATE

Of immediate priority for Petersfield was the provision of a site for a new secondary school, and the County Land Officer identified the Causeway Farm beyond the then gasworks (now the Tesco site) to be reserved for this purpose. Despite the determination of Miss Nora Tomkins, the Chairman of the Town Planning Committee, to put Petersfield on the map as a pioneer town in ‘what education should be now and in the future’, it was to be a further twelve years before her dream of a secondary school on this site was realised. The old (pre-war) senior and junior council schools in St Peter’s Road had become woefully inadequate and, even with the use of temporary hutted accommodation, it was clear that a fresh look at educational provision in the town was long overdue. The school leaving age had been raised to 15 in 1947, and this put even more pressure on the authorities to seek a solution to the overcrowding then prevalent in the town’s educational establishments.

Miss Tomkins had recommended to the Petersfield UDC that they ask the county council to consider provision for all educational needs at one location, from infancy to adult life, and comprising grammar, modern and technical sections in the secondary sector, in accordance with the provisions of the 1944 Education Act. She wanted Love Lane to be earmarked as this site for all the necessary buildings, but the UDC Chairman felt that the Causeway site would be preferable as it was much larger, could accommodate the school’s own playing fields, as the UDC was not intending to offer them the continued use of the football pitch in Love Lane, and would allow for expansion in the future. This debate marked the start of a long, frustrating saga about the educational needs of Petersfield children which Miss Tomkins was not to see resolved during her period of office. She had been the first elected woman member of the Urban District Council and retired from it in November 1945 after nineteen years’ service to the community.

The whole question of the type of secondary school to be chosen and where and when the building would take place, became the subject of considerable controversy and not a little prevarication for many years after the publication of the 1944 (Butler) Education Act. It was for this reason that the assumption was made that as Churcher’s College was a grammar school, the old Petersfield Senior School would become the new secondary modern school, in line with the educational definitions of the 1944 Act. However, despite the tacit acceptance of the title ‘Secondary Modern’ – a school badge and a navy-blue and yellow uniform had even been created, although few of the children’s parents could afford these – there was never an official naming ceremony and at various times between 1945 and 1957 the school was referred to as the Petersfield County School, the Petersfield County Secondary School, and even the Modern Secondary School. The pupils themselves knew it as PSM (Petersfield Secondary Modern), but the label (unfortunately for the children) carried with it a certain stigma, as it indicated a failure to obtain the 11-plus examination for entry to grammar school. In 1947, the Hampshire County Council added to the educational planning confusion which was unsettling the town by proposing an all-purpose (i.e. comprehensive) school for girls, and a secondary modern school for boys.

Yet another call for the building of Petersfield’s new secondary modern school was made in the spring of 1951. In the original development scheme for the town’s schools, the programme was to build a comprehensive school incorporating the Girls’ County High School and the secondary modern school in one building. However, the County Education Committee had still not reached a final decision and it was more than likely that the new school would house the former Senior Council School in St Peter’s Road and the local village schools. The former had a roll of nearly 400 between the ages of 11 and 15 and their classroom accommodation and playing space were hopelessly inadequate. As was the case in the war, supplementary halls in the town and the use of public grounds were hired to meet partially the educational needs of these pupils. A similarly desperate situation arose at primary level: the primary school had about 340 children in it and the roll was increasing year by year, with the result that, owing to lack of space, it was soon going to be impossible to admit any 5-year-olds.

Despite more calls by the parish councils for the building of a new secondary modern school for Petersfield, the project was again put on hold thanks to the restrictions on capital expenditure in the 1952 education budget, which forced another postponement. In addition to this setback, Mr E.J. Baker, the owner of the land, told the Hants and Sussex News that he did not intend to give permission for his land to be sold, as it would represent a loss to agriculture of valuable farming land. It was in the Causeway Meadows that it had been proposed to build the town’s new secondary modern school and, beside it, the school’s own playing fields, as the UDC was not intending to offer it the continued use of the future pitch in Love Lane. In the meantime, Mr E.C. Young was appointed Headmaster of the newly named Petersfield County Secondary School, and it was he who eventually saw the school through the difficult transition stage to its new premises in Cranford Road.

Churcher’s College and Peter Symonds School in Winchester had both applied for Direct Grant status under the new regulations, but both had been refused by the Ministry of Education. There were no Direct Grant schools in Hampshire at this time. However, Churcher’s College was granted voluntary-aided status in 1949, thus enabling its own governors to control its curriculum, school and boarding policy while Hampshire County Council financed its maintenance and controlled its pupil entries.

It was perhaps coincidental, but also thereby historically significant, that many head-teachers of Petersfield schools retired immediately after the war: Mr A.H.G. Hoggarth had been associated with Churcher’s College for thirty-five years, including eighteen years as its Head; Miss Emma Lowde had been the first and only Headmistress of the Girls’ County High School since its opening in 1918; Mr Wilfrid Bennetts had joined the staff of Petersfield Senior Council School in 1911 and succeeded Mr W.R. Gates as its Head in 1942. He had also played an active part in the life of the town and served on the Urban District Council for several years. His wife, Mrs Emily Bennetts, had been the Headmistress of Sheet School since 1919 and she also retired in 1946. At Bedales, Mr Freddie Meier, who had taken over the headship from the founder, Mr Badley, in 1935, was replaced by Mr Hector Jacks in 1946. Mr Jack le Grice, Headmaster of Churcher’s prep school under Mr Hoggarth, bought Broadlands in Ramshill and transformed it into his own Broadlands Prep School, preparing boys not just for Churcher’s College, but also for other grammar and private schools. The school was to survive successfully until Mr and Mrs le Grice retired some twenty-five years later. Another Prep School, Winton House, closed at the end of the school year 1946–7 when its Headmistress, Miss G.M. Williams, retired after twenty-three years’ service.

An educational era passed with the death in 1951 of Miss Annie Richardson who, with her sister Beatrice, had run Ling Riggs School in Sandringham Road for nearly half a century. They had come to Petersfield from London at the turn of the century and lived at 8 High Street, where their father was a bookseller. Thirty years later, the building was demolished by Woolworths for their new store.

Although Petersfield had lost two of its small private prep schools since the war, it shortly gained two more: Moreton House opened as a school in the old Hylton House in The Spain, and Dunannie began operating as Bedales pre-preparatory school in 1954. Dunannie, a large, partly seventeenth-century house between Petersfield and Steep, had become the centre of an experiment in friendship when young Germans and other Europeans had come to share their lives with young English students in 1948 under the auspices of The Friends Ambulance Group, which moved from London into the house as part of its relief work in postwar Europe. Dunannie moved ‘across the road’ into part of the Dunhurst premises in 1970.

The departure of evacuated children from the town at the end of the summer term in 1945 was as significant as it was sad. Emanuel School boys from London, who had far outnumbered the Churcher’s boys they had shared their school with, had celebrated the 350th anniversary of their foundation in May. The Headmaster, Mr C.G.M. Broom, spoke then of the ‘friendliness that had prevailed for six years between their hosts [Churcher’s College] and themselves as guests in Petersfield’. Similar sentiments were expressed by Miss Dorothy Chadwick, the Headmistress of Battersea Central School for Girls, who had shared the Petersfield Girls’ High School premises in the High Street and had held classes at Hylton House in The Spain and in various premises throughout the town.

In 1949, West Mark Camp School near Sheet Common, which had housed several hundred children evacuated from the Portsmouth area in the war, was chosen as the scene of a bold experiment in education. As a direct result of the successful wartime experience of bringing urban schoolchildren into a rural setting – for their own safety, but also enhancing their daily lives by giving them an appreciation of the countryside – ninety boys and sixty girls sent from the County of Middlesex arrived at West Mark Camp for a three months’ stay. The principal aims were to develop the spirit of living together and to create a mutual respect between townsfolk and countryfolk.

West Mark Camp was one of thirty country estates owned by the National Camps Corporation and let by them for varying periods to local education authorities as an experiment in boarding education.

THE MARKET DEBATE

At the meetings of the Petersfield Urban District Council in the immediate postwar years, a good deal of debate arose over the state and the quality of Petersfield cattle market. Projects were discussed for a new site for the market (the so-called ‘new market’) as the accommodation currently afforded in The Square was said to be poor, particularly with regard to the conditions for the livestock. A new site was suggested near Borough Farm (in Borough Road), but, in the view of one correspondent to the Squeaker, ‘this would lead the town to part with some of its ancient rights to a group of individuals who, having obtained that monopoly, proposed to exploit it for their private gain’. The council were prepared to discuss leasing the livestock rights. The auctioneers Hall, Pain and Foster and Hewitt and Lee abandoned the new market plan because of the costs involved and the opposition they had encountered to it.

A sheep auction by Jacobs & Hunt in The Square, early 1950s. (The News Group)

Sporadically during the history of the market there were allegations of cruelty to the animals, which remained tethered for long periods of the day; occasionally there were accounts of heifers or calves which broke loose and ‘rampaged’ through the town. One report in 1947 described a ‘horrible exhibition of savagery’ which ensued when a heifer broke free from its tether at the railings in The Square and was pursued through the market and town by a yelling mob of men and boys, who were smashing it across the head and face with heavy sticks. These allegations, however, were vehemently denied in the following week’s Squeaker. Nevertheless, regardless of the accuracy or otherwise of such reports, it is clear that market conditions aroused feelings of anger in some onlookers and these strongly felt concerns marked the beginning of the eventual demise of the cattle market (which finally closed in 1962). The RSPCA also called for the market to be abolished; it talked of the ‘shocking scandal’ of the animals standing in The Square from 9 a.m. until 4 p.m. with no facilities for sheltering or watering them and with them tethered in overcrowded conditions.

Meanwhile, protests by Petersfield traders over the displacement of farmers and their livestock by stallholders led to their demanding that the UDC take immediate steps to earmark a more suitable site for the livestock market. Petersfield was, nevertheless, still predominantly an agricultural-based community with rural interests and, in the late summer of 1948, over 5,000 people went to Bell Hill (now the recreation ground) to see the biggest agricultural show ever held in Petersfield – and the first since 1938 – organised by the Fareham and Hampshire Farmers’ Club.

Another rural era passed when the cultivation of hops at Seward’s Farm at Weston ceased after 142 years. Traditionally, for a fortnight every September, 24 acres of hops were pulled from the vines by more than eighty families, the vast majority of whom came from Portsmouth. Christopher Seward’s last crop at Weston after twenty-five years was picked in 1946. Hops were still grown at Buriton, however, and schoolchildren were still being given time off school to harvest the crop in September each year, just as they had done during the pre-war and war years. The main Petersfield hop farms brought into the district about £30,000 each season, the bulk of which went towards labour costs, but this sum does reflect the value of the whole enterprise to the community.

THESqueaker

The Hants and Sussex News, known to all (and, in an ironic fashion, to itself) as the Squeaker, remained as visually austere in 1945 as it had always been – perhaps consciously following the example of The Times, which resolutely retained its spread of small advertisements on its front page until Winston Churchill’s death in 1965. The Squeaker (as it will be referred to here) was a four-page broadsheet costing 1½d, with reports from Petersfield Petty Sessions and the two local councils (Urban and Rural) on the front page, small adverts on page two, announcements of forthcoming events on page three, and news articles and letters to the Editor on the back page.

However, it was not to remain immune from the postwar evolution in local life: with a change of ownership to Mr A.D. Millard, a London book publisher, in 1945, the structure and look of the paper underwent considerable modernisation over the next five years. It reached a wider readership, increased its circulation figures and published a short leading article each week. In 1946, its austere aspect and solemn prose gave way to larger front-page headlines, bolder typography in its page two advertisements and a wider reporting of news from Midhurst and ‘Round the District’. Its first lurid headline (‘Ran to girl with knife in his back’, on the stabbing of a boy in Liss by a sailor) and its first photograph (of Kathleen Money-Chappelle at the closure of her ‘Home from Home’ canteen) appeared and, in 1947, linotype was adopted, more pictorial adverts started to feature and the paper increased in size from four pages to six. In 1948, under its new Editor, Hardiman Scott, the Squeaker appeared in a new dress. For sixty-five years the front-page title of the newspaper had been printed in heavy Old English Gothic type. The new type adopted saved 7in of space as the lines were set closer together. The paper expanded to six pages in 1949, and its price rose from 1½d to 2d that year. It began to carry half-page advertisements and banner headlines of a whole page width. Many more photographs began to adorn not only the front, but also the inside pages.

Petersfield Post mastheads. (Author’s Collection)

It became more of a campaigning newspaper too. For instance, it called for a referendum on the future of Petersfield market, adopting the stance that change might be for the better now that cattle were being transported to and from further afield on market days. Also in 1947, the Squeaker’s new Comment column, dwelling on the attraction of Petersfield as a visitor town, suggested that ‘we would do well to give them a bigger welcome’. It felt that, without sacrificing any of its present charm, the Heath could be more tempting, and suggested the creation of a small beach and a paddling pool on the north side of the Pond, a tea house nearby, and greater publicity for the town’s summer sports of cricket and golf, both established favourites on the Heath for generations. Furthermore, the local amateur dramatic societies could be encouraged to provide outdoor entertainment on the Heath, with Shakespeare given ‘an open airing’, concerts by the Victoria Brass Band, and more attention drawn to the town’s historical and architectural beauties. To promote all this, a greater use of advertising was needed in neighbouring towns.

The Petersfield Weekly News had begun life in 1883 and had become the Hants and Sussex News in 1891 when Frank Carpenter became its Editor and the business was taken over by Mr A.W. Childs. Later, it removed to premises at the bottom of the High Street (now Your Move), then to Childs bookshop site (now Somerfield). The pre-war paper was known well outside the town for its intelligent and literate reporting. Indeed, it was also known as far afield as Africa: the first Mrs Rowswell, who had opened her newsagent’s in the High Street in 1916, passed on ownership of the shop to her two daughters, one of whom had a daughter living in Southern Rhodesia and who received the newspaper weekly. She in turn passed it to the natives who used it to roll their cigarettes in, as it had such fine, combustible paper!

PETERSFIELD IN THE MEDIA SPOTLIGHT

During a programme in a BBC radio series entitled Thank You for Your Letters, broadcast on the General Forces Network in 1946, a commentary on Petersfield described the town as ‘prosperous and bustling’. The Heath, Charles II, the Jolliffe family, Churcher’s College and St Peter’s Church were all mentioned in a series of brief verbal pictures.

Three years later, the broadcaster Brian Vesey-Fitzgerald was considerably more negative in his book Hampshire and the Isle of Wight in which he describes Petersfield as ‘a pleasant, rather sleepy town, which gives me the impression that it missed success centuries ago, and has been waiting ever since for another chance to turn up’. He called the statue of William III ‘quite the most ridiculous statue in England’, the manners in its tea shops and cafés ‘leaving much to be desired’, and he doubts if Petersfield would ever be considered a ‘first-class season’ town.

However, under Hardiman Scott, Frank Carpenter’s successor as Editor of the Squeaker, Petersfield’s association with the media was particularly favourable. This was exemplified later in 1949 when it was learnt that after only one year in the post, Mr Scott was leaving to join the staff of the BBC Midland Region. He had been in Petersfield since the end of the war and had identified himself closely with the cultural life of the town in that time. His talents as a poet, novelist and, above all, as a broadcaster were to ensure that his name became a household word in Britain during the 1950s. It may not have been entirely coincidental that it was Hardiman Scott’s Squeaker which had provided the information and pictures of the town from which two film companies would select their locations for two films to be made in the autumn and winter of 1949 and 1950.

In the autumn of 1949, many Petersfield schoolchildren played as extras in the film The Happiest Days of your Life, directed by Frank Launder and filmed at Byculla School in Rake, a private girls’ school later named Little Abbey. The stars of the film were Margaret Rutherford and Alastair Sim. It is hardly surprising that the newly recruited, budding stars still remember being paid handsomely for the enjoyment of waving from the coaches as they arrived at the school, playing lacrosse, marching noisily around the building, then participating in a grand pillow fight in the ‘dorms’! Churcher’s boys even had some speaking parts. To cap their joy, they were taken to London to see the premiere in Leicester Square.

In February 1950, the Hollywood film star Robert Montgomery was in Petersfield Square to direct some sequences for the film Your Witness, in which he also starred. Hundreds of people thronged the Market Square and took part in the crowd scenes.

The same month, nearly five hundred people crowded into the town hall to watch and hear the BBC programme chairman Guy Mackarness and the producer Rupert Annand invite about forty local townspeople to answer questions on topical issues sent in by listeners. The recordings were destined for a thirty-minute programme entitled Speak your Mind to be broadcast later on the West of England Home Service.

Sixteen months later, Petersfield went on the air again: the town was chosen for the staging of the 100th edition of the BBC’s Any Questions? Nearly seven hundred people were in the ‘Large Hall’ (Festival Hall) to hear Freddie Grisewood, the question master, open the programme and the panel of Ralph Wightman, Sir Steuart Wilson (a former Bedales Music Master), Sir Richard Acland and Sir ‘Bob’ Boothby (respectively Labour and Conservative politicians) answer the public’s questions.

THE HOUSE-BUILDING PROGRAMME

Among the public works projects undertaken in the immediate postwar period was, of course, a substantial housing programme. The Urban District Council site in Cranford Road which it had purchased in 1945 from the two owners, Mr Ted Canterbury and Mr E.J. Baker, was designated in 1946 to receive a total of twenty-eight dwellings. The first few houses at the Causeway end of the road had been completed before the war; however, by mid-1947, only three of the new properties had been completed and occupied, as there were only twenty men working on the project and with an overtime ban in force. In the town, there were still some eighty German POWs, and these men were temporarily employed on the council’s housing schemes to help with the building of streets and sewers; they – along with nearly half a million others who had been similarly detained in Britain after the war had ended – were eventually repatriated to Germany after spending ten months working in Petersfield. The general layout of the Cranford Road–Borough Grove–Grange Road estate was thought to be extremely wasteful by the infrastructure engineers, although of course it looked extremely attractive on the plan. In this respect, it resembled more a private development than a council project, with its central stream and ample green spaces and trees.

Despite Petersfield UDC’s relatively slow start to the postwar house-building programme, due mainly to the policy of ‘no pre-fabs’, the 1948 change of heart and decision to order 26 ‘Reema’ houses for Highfield Road took the total number of homes created by the end of 1949 to 80, with a further 34 under construction. By comparison, Biggleswade (Bedfordshire) had 248 (temporary or permanent) houses completed, Saffron Walden (Essex) 184 completed, and Stevenage (Hertfordshire) 160 completed. These Reema houses, built by Reema Construction Ltd, although prefabricated in their method of construction, were in fact considered to be permanent homes and were the subject of a compulsory purchase order by the Ministry of Health, thus intimating their approval. Construction on the Highfield Road and Borough Grove sites began in 1949 and was completed in little over a year.

The highest number of houses built in the UDC and RDC (Rural District Council) areas in one single year since the war was achieved in 1950, with 327 permanent homes completed, almost double the total number of those built between 1945 and 1949. The population of Petersfield recorded at the 1951 census (6,616) had also risen rapidly, by 22 per cent, since 1931.

By 1949, Petersfield felt that it was emerging well from the war and the UDC presented a note of success in its deliberations: the collective achievements of a new sports ground at Love Lane; a recreation ground at Bell Hill; an enlightened outlook on cultural activities which had produced grants for the Musical Festival and the repertory theatre; and the purchase of thirty-two Reema houses for Cranford Road exemplified the new optimism. Finally, a proposed boundary plan which merged the urban and rural areas outlined a possible new administrative convenience. In terms of population, it was expected that the town would double in size, and planning decisions were beginning to be made with this in mind.

Reema houses in Borough Grove, 1980s. (Petersfield Museum)

In the Rural District, more than two hundred families were still living in requisitioned premises after the war and there were 475 families waiting to be housed. In the UDC area, the problem was not so acute: only 10 families were in requisitioned houses and 15 families in the huts at ‘Oaklands Camp’, built at the top end of Oaklands Road by the Ministry of Works during the war to house a civil defence unit. The first families of squatters had moved there in 1946 (where they shared the camp with the German POWs employed in building the Cranford Road estate), while they waited to be relocated in council houses. In fact, the UDC area house-building rate had slowed down by nearly a half by August 1952, there being a total of twenty-nine houses built between June 1951 and June 1952 owing to protracted negotiations for the possession of sites. By November 1952, however, the last house on the Cranford Road estate was completed and the link through to Borough Road effected, the biggest building scheme in the history of the Petersfield UDC. This substantial development was regarded as a ‘model small town’ with a shop incorporated into the estate consisting of a total of 219 dwellings and 68 Reema houses.

One feature of this period was the tight working unity forged between the UDC, the developers and the civil engineers who worked on the major projects around the town: as Borough Engineers and Surveyors, first Harold Longbottom, then, after his retirement in 1953, John Thomas, were responsible for water supplies (before the Wey Valley water company took this over), the market, highways, the Taro Fair and the Heath, sewerage and new housing estates such as the large Cranford Road–Borough Grove complex. It was John Thomas who introduced sodium street lighting to Petersfield (in the Causeway) in the 1960s, who rebuilt the sewage works in the 1970s, and who was responsible for alleviating the huge problem of flooding which had bedevilled the town for decades.

SOCIAL AMENITIES

Far-reaching plans for the future provision of social amenities in Petersfield were discussed by the Urban District Council in 1948: one proposal was for a children’s recreation ground at Bell Hill, with football and cricket pitches, swings and a paddling pool; another was for a sports ground at Love Lane with rugby and football pitches, a swimming pool and a running track; a third facility was to be a car park and perhaps a bus station in the centre of town. About forty people representing Petersfield societies had also called upon the UDC to provide a community centre for the town, while an equally vociferous call was made for a youth centre.

One activity popular with local young men at the time was cycle speedway: Petersfield was represented by the ‘Highfield Cobras’ whose home track was at Kimber’s Field (now Kimbers) and they had many hundreds of followers who went to their competitions against other teams from Hampshire and beyond. An annual cycle speedway match was held at the British Legion Fête in the Grange Field (now the site of The Petersfield School). With the return of Petersfield’s newly demobbed servicemen, the town’s former clubs and societies began to start up again. There were jobs available for the returnees too: the Post Office was a big employer, the Itshide rubber factory took on staff, the local council offered manual jobs, and some people went up to Longmoor to find work. It was as if Petersfield, unlike Horndean for example, was self-sufficient in labour supply and demand.

Charles Dickins, Scoutmaster of the Petersfield Troop, reported that three youth clubs had started since the war and had died out. It was Mr Dickins who had held the Scout troop together for thirty-seven years with a break of only three years during the First World War; he had been engaged on youth work for at least forty-two years during his lifetime and his belief was that, as the 1st Petersfield Scout Group (Lord Selborne’s Own) had been formed in 1909, it must have been one of the oldest in the country. Their most recent achievement was the wartime collection and sorting of waste paper; the eighty or more boys had worked in relays on the organisation of the salvage, and had even bought a baler and two storage sheds, which were erected at the back of the Scout hut in Heath Road which the Scouts had moved into in 1915. An average of 2 tons of paper was collected each week during the war years.

The town library, which had moved premises three times since it had started in 1926, now took over Winton House in the High Street. Its first home had been above Mr E.J. Baker’s butcher’s shop (now Superdrug), then the Working Men’s Club in Station Road, then a special room was dedicated to it in the town hall, until the demands of the war forced it to move back to the Men’s Club. The Librarian, Mr Edgar Morris, had remained in his job throughout all these years of change and was now congratulated on his ‘yeoman service’. A year later, the Squeaker joined those who were campaigning for a designated new library site in the town.

With the advent of the National Health Service in 1948, the old Petersfield Cottage Hospital became a state-run hospital. However, doctors in the district, who until then had consistently opposed the emergent National Health Service introduced by the Labour government of Clement Attlee, now decided to follow the advice of the BMA Council and join the service when it started in July of that year.

A further major consideration in these developments was the success of the Petersfield Cottage Hospital and how it was to cope under the new regime: the government had taken over the hospital and placed it within the scope of the Portsmouth Group Management Committee. However, Miss Bates, who had been Matron at the hospital for nearly twenty years, agreed that the hospital was running ‘just as smoothly as ever’, apart from the form-filling which had accompanied the change in management structure.

Meanwhile, the Petersfield Isolation Hospital in Durford Road (on the site of Home Way), which was closed in the middle of 1948, reopened in September 1949 as ‘Heathside’ with the aim of providing beds for up to forty chronically sick patients in three wards. Furthermore, in 1950, it was proposed to spend £2,500 on converting the old Public Assistance (or Poor Law) Institution in Ramshill (more generally referred to as the Workhouse) into a new Public Health Centre; but this project was later transferred to Swan Street on a site which had already been identified as a potential site for a fire station.