9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

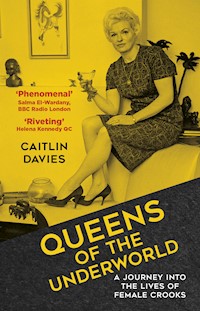

'This book is an extremely important part of women's social history. Read it!'- Maxine Peake Robin Hood, Dick Turpin, Ronnie Biggs, the Krays … All have become folk heroes, glamorised and romanticised, even when they killed. But where are their female equivalents? Where are the street robbers, gang leaders, diamond thieves, gold smugglers and bank robbers? Queens of the Underworld reveals the incredible story of female crooks from the seventeenth century to the present. From Moll Cutpurse to the Black Boy Alley Ladies, from jewel thief Emily Lawrence to bandit leader Elsie Carey and burglar Zoe Progl, these were charismatic women at the top of their game. But female criminals have long been dismissed as either not 'real women' or not 'real criminals', and in the process their stories have been lost. Caitlin Davies unravels the myths, confronts the lies and tracks down modern-day descendants in order to tell the truth about their lives for the first time.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

To Maureen Gill, Queen of the Bargain.And in memory of Bruce Gill, with love.

First published 2021

This paperback edition published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Caitlin Davies, 2021, 2023

The right of Caitlin Davies to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 911 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Prologue: Blonde Mickie

Introduction: Woman of the Underworld

1 Mary Frith: Jacobean Pickpocket and Fence

2 Ann Duck: Eighteenth-Century Street Robber

3 A Conscious Mistress of Crime

4 Ladies Go A-Thieving

5 Emily Lawrence: Victorian Jewel Thief

6 Mary Carr: Queen of the Forty Thieves

7 Alice Diamond and Maggie Hughes: The Forty Elephants

8 Lady Jack: Shop Breaker

9 Queenie Day: The Terror of Soho

10 Rescued from the Footnotes

11 Lilian Goldstein: Smash-and-Grab Raider

12 The Forty Elephants Bar

13 Noreen Harbord: Queen of the Contraband Coast

14 Zoe Progl: No. 1 Woman Burglar

15 The Great Escape

16 Shirley Pitts: Queen of the Shoplifters

17 The Criminal Masquerade

18 Liberation of the Female Criminal

19 Chris Tchaikovsky: Queen of Charisma

20 Looking for Trouble

21 Gangsters’ Molls

22 Joyti De-Laurey: Queen of Cash

23 Lady Justice

Sources

Select Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Other Titles by Caitlin Davies

PROLOGUE

BLONDE MICKIE

On the morning of Easter Monday 1960, a petite, grey-eyed woman called Zoe Progl set off for work. She was wearing her usual outfit, a sporty tweed suit, brown flat-heeled shoes and a pair of semi-rimless spectacles. Her dyed blonde hair was pulled back into a chic hair bun, and she carried a large black handbag. It was unseasonably warm that April, so instead of her usual leather gloves, she wore a fashionable white nylon pair. The 32-year-old passed quite unnoticed on the train from London to Brighton, just another harmless schoolmarm heading to the seaside, along with thousands of others. But Zoe Progl was a day-tripper with a difference.

Around two o’clock that afternoon, as holidaymakers thronged along the beach and promenade, Zoe made her way to a Regency house in one of the town’s most exclusive squares. She knocked on the door of the ground-floor flat, and when no one answered she rang the bell. Zoe was an expert at ‘drumming’ – ensuring that no one was home when she called – and she knew how to blend into her surroundings as if she belonged.

This was no impulsive trip, the flat belonged to a wealthy wholesale tobacconist who was said to keep a few thousand ‘readies’ at home, and Zoe had already spent several days casing the joint. Once she established that the flat was empty, she took a ‘loid’ from her handbag. It was the main tool of the housebreaker’s trade, a narrow strip of celluloid, about 2in wide and sharpened to a fine point. She slipped the loid between the wedge of the door and the lip of the lock and let herself in.

Zoe Progl had been a professional crook for fifteen years; she’d once stolen £250,000 worth of furs in a single evening, and a few months earlier she’d been arrested in London after breaking into a block of flats in St John’s Wood and stealing a fur stole, Tiffany jewellery and a fat wad of dollar notes. ‘Blonde Mickie’, as she was known by the press, was now on bail, but as far as she was concerned, this was simply a licence to go on grafting.

The Brighton flat was sumptuously furnished, but despite rifling through every room, all she found was £11 in cash. Disappointed but not deterred, Zoe headed to a different address and an hour later she was forcing open the door to a seaside mansion. Diamonds were a girl’s best friend, she reasoned, and she wanted some new friends. In the master bedroom, she found some choice items of ‘tom’ – tomfoolery or jewellery – carelessly dropped on a dressing table: rings, bracelets and brooches worth thousands of pounds. Zoe could immediately tell if an item was genuine and she’d recently stolen a diamond ring from a Mayfair apartment worth around £650, the average annual wage for a woman in 1960.

She gathered up the jewellery on the dressing table and put it in her handbag. The woman who owned them wouldn’t mind very much, she told herself – no one kept valuables like these without making sure they were well insured. She might keep a piece as a souvenir to attach to her own gold charm bracelet, which now had several pieces lifted from some of the stateliest homes in England, including a miniature gold Cadillac.

Zoe let herself out of the Sussex mansion and returned to London in a merry mood. But a few days later, the Flying Squad arrived at her Clapham flat, and Zoe Progl learned that she’d made a serious mistake. As she’d broken into the Regency flat, the strip of celluloid had torn the right index finger of her fashionable nylon glove. Zoe had left a fingerprint, and Scotland Yard had just caught Britain’s No. 1 Woman Burglar red-handed.

She was convicted of housebreaking and sent to Holloway Prison, the most notorious female jail in the UK, to serve two and a half years. But if the authorities thought she would take her punishment, they were wrong. On 24 July 1960, Zoe Progl climbed over the 25ft perimeter wall in her prison-issue bloomers, in the most successful jailbreak in seventy-five years.

She went on the run for forty days, along with her 4-year-old daughter Tracy, and by the time she was recaptured, Zoe Progl was an underworld celebrity. But, back in Holloway once more, and now facing an additional eighteen months, she had the chance to think things over. As she sat alone in her prison cell, Zoe decided she’d had enough of crime. She no longer wanted to be Queen of the Underworld; instead she wanted to forget her criminal past. She would write her memoirs, to serve as a warning to others – crime was no way of life for a woman. ‘I am deeply sorry,’ she confessed. ‘I now have the chance of living an ordinary, decent life and fitting into society; the very society which I have abused for so long.’

Zoe owed her three children comfort, security and love, and when the prison gates opened on the morning of her release, Britain’s No. 1 Woman Burglar had retired. Her criminal days were over – from now on, she would devote herself to being a good wife and mother.

INTRODUCTION

WOMAN OF THE UNDERWORLD

I’m walking down a quiet residential street in south London on my way to visit Zoe Progl’s daughter. It’s the summer of 2018 and in my bag, I have a copy of her mother’s autobiography, Woman of the Underworld, a thrilling tale of a life of crime and her escape from Holloway Prison. A few weeks ago, I posted a photo of Zoe on Twitter, on the anniversary of her jailbreak, and I had no idea her daughter was even alive, until she sent me a tweet, ‘Hey, that’s my mum!’

I unlatch a wooden gate, climb the steps to a Victorian maisonette, and ring the bell. I’m not sure who or what to expect, but I want to know what happened after Britain’s No. 1 Woman Burglar went straight.

When a slim, dark-haired man about my age opens the front door, I hesitate. ‘I’ve come to see Tracy,’ I explain.

The man gestures me into the front room, the windows half open on this sunny Sunday morning. Tracy Bowman is sitting on the sofa, dressed in a red tartan shirt and black trousers. She’s in her early sixties, blonde hair falling in ringlets around a delicate face, her make-up careful and precise. I’m not sure how to start the conversation, but Tracy exudes an air of total serenity.

‘Mum was a burglar,’ she says. ‘It’s nothing for me to hide. I talk about her all the time.’ She points to a vase in the corner of the room, ‘Those are her ashes right there.’

Tracy’s partner, Andy, goes to the kitchen to make tea and I take out my copy of Woman of the Underworld. ‘Did your mum really write this in her prison cell?’ I ask, putting the book on the table.

Tracy nods, ‘She wrote the original draft, but then a News of the World journalist changed it. He wanted more sex and drugs, and he tried to make everything juicier.’

‘Oh,’ I say, a little worriedly, because I’ve recently quoted from Woman of the Underworld in a history of Holloway Prison. I look at the book on the table, wondering which parts of the story the journalist changed. But first, I want to show Tracy some old newspaper clippings about her mother’s famous jailbreak.

I take out a copy of the Daily Mirror from 25 July 1960; the headline is ‘Blonde Breaks Out of Holloway’. It includes a blurry headshot of ‘Blonde Mickie’, as well as an annotated photograph of her escape route, the ladder still in place against the wall. The article begins with a phone call Zoe made to a friend two hours after the escape. ‘I’m out ducks,’ she told her, ‘and I’m alright.’

Tracy reads the first paragraph and laughs, ‘Mum wouldn’t have said that, she never said “ducks”. They’ve made that up.’ Tracy was too young to remember much about the escape, but her mother took her to a caravan park in Devon and ‘it was like being on holiday’. After forty days on the run, Zoe was recaptured and sent back to prison and Tracy went to live with a friend of a friend.

‘All the gangsters and the villains looked after me,’ she smiles. ‘I got great big chocolate eggs at Easter!’

But she still didn’t know about her mother’s life as Britain’s leading woman burglar. ‘Even though I’d visited her at Holloway, I’d always thought she was at the dentist. My friends would ask, “How long has your mum gone to the dentist for, Tracy?” And I’d say, “Seven years”.’

We both start laughing, but then I stop, picturing a 4-year-old child who has no idea her mother is locked up in prison.

Andy comes in with the tea and I take out a second newspaper clipping, from 1963. The headline is ‘Underworld Queen says: “I abdicate”’, and the photograph shows Zoe Progl elegantly dressed in black with newly bleached hair, the perimeter wall of Holloway Prison looming up beside her. She was going to look for honest work, she told the Daily Mirror, she’d learned her lesson and ‘people who steal should be made to pay back the money’. Tracy reads the article and shakes her head, ‘Bloody hell, she would have had to be paying back forever.’

I hand her a third newspaper clipping, from April 1964, entitled, ‘The bride who was a gangster’s moll’. This time Zoe wears a box hat with a veil; she looks beguilingly over one shoulder, clutching a bouquet of flowers and a large silver horseshoe. She has just ‘secretly’ married 24-year-old salesman Roy Bowman, a furtive-looking man with slicked back hair. ‘He wasn’t a salesman,’ says Tracy, ‘he’d just come out of the merchant navy. And look,’ she points at the picture, ‘he’s wearing a false moustache and goatee because he didn’t want to be recognised.’

I say this seems a bit strange when he’d agreed to be photographed for the Daily Mirror. Tracy laughs, then she gazes at the photo, ‘Isn’t mum beautiful? She was such a tiny thing, so delicate.’

According to the Mirror, Zoe was no longer a gangster’s moll; instead, she was about to become a respectable woman and her new husband promised her children would ‘have a future and complete security’.

Tracy finishes reading the clipping and makes a face. ‘It was the worst time of my life,’ she says, ‘having him on the scene. I was safe before Roy. He was an arsehole. We were all petrified of him. He punched us. I weed myself when he came in. He broke mum’s jaw and nose.’ Tracy stops and shakes her head, ‘Mum was such a strong woman, it was odd that she put up with him.’

Zoe eventually split up with her husband after a vicious custody battle, and when I ask what happened next, Tracy relaxes and smiles again, ‘Mum went straight back to thieving!’

She did? I sit back in my chair, surprised. I’ve never read anything about this; I haven’t found a single newspaper report on Zoe Progl after her release from Holloway and her marriage to Roy Bowman. So she refused to live the respectable life after all?

Tracy nods, ‘She said crime was better than sex; it was the thrill she got. She always said she didn’t regret anything.’

But, I say, at the end of her autobiography she says she’s very sorry and promises to go straight.

‘Mmm,’ says Tracy, ‘that went well then.’

After Roy Bowman left, her mother’s underworld friends started coming round again. ‘They were her old associates,’ explains Tracy, ‘and it was such a buzz, a house full of people, police crashing the door down, she loved it. Our home was a hub. Everyone met there for a roast, to talk about who had nicked what, what jobs were coming up, and all the crooks came to her flat to place orders for what they wanted beforehand.’

One day, while Tracy was sitting doing homework with a friend, three men in balaclavas ran in. ‘They’d just robbed a jeweller’s. They were trying to burn all the packets the jewellery came in by throwing them on the fire. But it was all normal to me, it wasn’t frightening. When I went to my friend’s house and had Yorkshire pudding, that was exciting to me! It was drama all the time at home, gangsters and cops, and I was part of it all.’

‘Then what happened?’ I ask.

Tracy sighs, as if it’s inevitable, ‘Mum was sent to prison again.’

‘She was?’ I’ve never read anything about this either. As far as I knew, Zoe Progl’s 1960 conviction for housebreaking, and her subsequent escape and re-arrest, was the last time she was ever jailed.

‘It was for fraud,’ Tracy explains. ‘Then when she came out, she started shoplifting again. She used to go out missing, for days on end. One time, she was caught shoplifting at Cecil Gee’s, the menswear shop in Oxford Street. She’d been gone for a week when we got a call from Bromley cops. She’d pulled the sleeves off her coat, she was struggling so much when they arrested her. She went out in a coat and came back in a waistcoat!’

Tracy speaks of her mum with such fondness and a smile that fills her eyes. She’s proud to be Zoe Progl’s daughter and wants her to be remembered, which is why she responded to me on Twitter. But she’s also worried about sounding disloyal.

‘Mum lived by her own rules,’ she says. ‘She had a different set of morals from anyone else I knew. Nothing she did was bad or wrong, she didn’t harm anyone … but for us.’ Tracy looks at the vase in the corner of the room, ‘Sorry, mum, but kids were pushed to one side; it wasn’t glamorous from the inside. She was good fun, but she wasn’t maternal. When she was here, she was a great mum.’

Tracy is silent for a minute. ‘I never cried when she died. Her funeral was in West Norwood or Croydon, I can’t remember, it’s all a blur. All the gangsters arrived in Rollers and people were craning their necks to see them. The Rollers stopped and all these little old shrunken men got out with fedora hats on!’

I finish my tea; it’s time to go. Andy is heading off to football practice and Tracy is going for her daily swim at a local lido. I ask if she’ll sign my copy of Woman of the Underworld, and if I can come back another day to ask more about the book.

‘Was your mum really Britain’s top woman burglar?’ I ask, as I stand on the doorstep to say goodbye.

Tracy shrugs, ‘I don’t know of any others, do you?’

‘No,’ I say, because I’ve never heard of a single top woman burglar.

‘You would have loved mum,’ says Tracy, ‘and she would have loved you.’

I smile, feeling pleased. ‘Do you think so?’

‘Yes. I was a bit worried about meeting you, I thought you might judge her.’

All the way home, I think about the assumptions I’d made about Zoe Progl. I’d read Woman of the Underworld and countless newspaper reports about her prison escape, but perhaps I’d slightly dismissed her criminal career, because if she really was Britain’s top woman burglar, then why hadn’t I heard of her? I assumed she’d given up the criminal life, as she promised to do at the end of her autobiography, but she hadn’t. Her abdication wasn’t true, and neither was her apology. Zoe Progl wasn’t sorry, and she hadn’t had any regrets; instead, she’d loved it. Crime had been better than sex.

There have been no further books about Zoe Progl; her life hasn’t inspired any documentaries, dramas or films, and there has been nothing to set the record straight. I wonder if the same thing has happened with other female crooks. Have they had their stories twisted, or not had their stories told at all? And if Zoe Progl was Britain’s No. 1 Woman Burglar, then who came before and after her? Did she have any predecessors in the world of crime? What about bank robbers, or jewel thieves or smugglers, were there any women? Can I find others who pursued the criminal life, who were respected and had fun? Are there other women out there who were happy to call themselves ‘Queen of the Underworld’?

When I get home, I type ‘British female criminals’ into a Google search and up comes a list of the ‘most notorious female criminals in British history’. There are five ‘serial killers’, a murderer, a suspected terrorist and a pirate. I click on Wikipedia, which lists seventeen women, including several transported to Australia for theft in the eighteenth century, as well as a suffragette. A subcategory provides eighteen English female criminals, but nearly half of these were convicted of murder.

I look up The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, where the category ‘law and crime’ has around 4,000 entries, but only 5 per cent are women, and many are victims – of murder, abduction, kidnapping, marital abuse – rather than perpetrators. But as for male criminals, they are everywhere, from Robin Hood to Dick Turpin, Jack the Ripper, Dr Crippen, the Great Train Robbers and the Krays. Male crooks have inspired fiction and biographies, feature films, dramas and documentaries. They’ve been taken seriously and turned into cultural icons, lionised in exhibitions, studied in academic papers, included in the national curriculum for schools. But what about their female counterparts, where are their stories?

A few weeks later, I take the train to the National Justice Museum in Nottingham, which has the largest collection of objects and archives relating to law, justice, crime and punishment in the UK. If I’m going to find some female crooks, this seems like a good place to start. I enter the museum’s Crime Gallery and come face to face with the wooden dock from Bow Street Magistrates’ Court, one of London’s most famous courts. I step up onto the dock and take my place in the middle, holding onto the thick black railings.

Opposite is a mural of twenty people who once stood here waiting to hear their fate. I can only see three photos of women. One is a group of suffragettes; another is Katherine Gun, who exposed a US plot to spy on the UN in 2004. The third, strangely, is the singer Ms Dynamite, tried at Bow Street in 2006 for slapping a police officer.

I keep looking at the mural. Surely there are other women who could be included here? What about Zoe Progl? She appeared in the Bow Street dock in the autumn of 1960, after the Flying Squad tracked her down to a flat in London and ended her forty days on the run.

I wander around a display about the Great Train Robbers who, in 1963, stole £2.6 million from a Royal Mail train. The museum certainly has a lot of artefacts: a glass cabinet containing keys and monopoly money, a map and floor plan of the farm where the gang hid out, and a combat jacket worn by one of the robbers. I move on to another display about Cesare Lombroso, the ‘father’ of modern criminology, whose book Criminal Woman, the Prostitute, and the Normal Woman, first published in Italian in 1893, was regarded as a classic. He argued that the majority of female criminals are ‘merely led into crime by someone else or by irresistible temptation’. Women were naturally conservative, he explained; we were also clumsy and lacked courage.

I walk next door to another exhibition, ‘Liberated Voices: Stories of Women (In)Justice’, where I read about Charlotte Bryant, hanged for poisoning her husband in the 1930s, and Beatrice Pace, acquitted of murdering her abusive husband in the 1920s. Then comes Alice Burnham, one of three ‘Brides in the Bath’, murdered by George Joseph Smith in 1913. And here is the actual bath she was killed in. It can’t be, I think, as I walk cautiously around the Edwardian bathtub. Why would anyone put that on display?

I’ve been at the National Galleries of Justice for a few hours now and I’ve seen quite a few victims, but I still haven’t found one successful female crook. I head to the courtroom, but I’ve missed today’s performance, a re-enactment of the trial of Joan Phillips, a ‘legendary Nottingham highwaywoman who passed herself off as a man’. At last! A real-life criminal woman.

I read some of the papers laid out on the tables. Joan was executed in 1685 and hanged on the gallows in Nottingham. But I later realise that the main source of her story appears to be a highly unreliable eighteenth-century book, whose author was known for making things up.

If I can’t find many criminal women online or in the National Galleries of Justice, then I’ll have to begin with the few women who have been remembered and start off as far back as I can go …

1

MARY FRITH: JACOBEAN PICKPOCKET AND FENCE

At the upper entrance to Shoe Lane, an ancient alley in the City of London, roadworks are blocking the traffic. A lorry attempts to deliver a load of gravel and as a bus inches its way onto Charterhouse Street, drivers begin sounding their horns. I head down Shoe Lane and away from the noise, passing modern office blocks with walls of reflective glass and then the medieval church of St Andrew Holborn. The lane is wide, but no one is about, aside from a woman rattling the wheels of her suitcase along the pavement.

Back in the seventeenth century, this alley was cobbled, and lamp lit, a claustrophobic passage lined with timber-framed houses that would be burnt to cinders in the Great Fire of London. There were tenements here, as well as businesses belonging to signwriters and broadsheet designers. Street vendors gathered to sell their wares on Shoe Lane – the fishwives, orange-women and gingerbread men – while visitors flocked to the local cockpit and alehouses. Diarist Samuel Pepys, who was born nearby, described one as ‘a place I am ashamed to be seen to go into’.

The area was known for thieves and ‘bad women’ and featured in several criminal trials. One afternoon, a gentleman strolling down Shoe Lane was thrown to the ground by a gang of pickpockets, and a few seconds later, his valuable watch was gone.

The City of London was home to around 200,000 people in the early 1600s, but there was no police force as such. Watchmen, largely untrained and ill-equipped, patrolled the dark alleys with staffs and lanterns, while parish constables arrested people after they’d already been caught. Most victims of crime had to catch the perpetrator themselves, to raise the ‘hue and cry’ and call for constables and passers-by to help, then take the offender to court at their own expense. If they couldn’t find assistance in time, the thief simply escaped through the narrow, twisting streets.

I carry on down Shoe Lane and the alley opens up, a nearby bar advertises a five o’clock cocktail club, while a woman sits on the pavement holding a sign that says ‘hungry’. The lane narrows again, and I come to a security booth and rows of City of London bollards set across the width of the street. The City has traditionally been London’s financial heart, and this is a sensitive area in terms of security.

Today, Shoe Lane is home to accountancy, law and banking firms, including the European headquarters of the American giant Goldman Sachs. I look down the lane and see a man suddenly stop and take a card from his pocket, then he flicks it against a black shiny wall. Part of the wall opens, the man slips inside, then the door closes and becomes a blank wall again.

It seems like a very secretive way to go to work, and I approach the security booth to ask if the building is part of Goldman Sachs. But the guard inside doesn’t answer. Instead, he looks over my shoulder as if I’m a decoy whose job it is to distract him. I point down the alley and ask again, ‘Is that shiny black wall part of Goldman Sachs?’ Still the security guard doesn’t answer. I tell him I’m looking for where the infamous Moll Cutpurse once ran her business. Isn’t it funny, I ask, that the country’s most notorious criminal worked here and now it’s home to investment bankers?

The security man finally relaxes. ‘Nothing changes,’ he laughs, ‘nothing changes.’

A few moments later, I emerge onto Fleet Street, with the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral in the distance. On my right is the front entrance to Goldman Sachs, an enormous columned building adorned with a gold-rimmed clock. On the other side of the road, and almost directly opposite, is Salisbury Court. So it was here, somewhere on this spot, that the most famous female criminal of the seventeenth century ran her business.

The story of Moll Cutpurse has appeared in numerous books and articles, and she is one of very few female criminals still, to some extent, known today. Yet, the reported details of her life are frequently contradictory and confusing. Her real name was Mary Frith and she was born in 1584, just north-east of Fleet Street. Her father was a respectable shoemaker, and her parents lavished their only child with tenderness and love. But Mary displayed a ‘boyish, boisterous disposition’ right from the start, and she couldn’t endure the sedentary life expected of girls. She was a ‘tomrig’ – a rude, wild tomboy, who delighted only in boys’ play and pastimes. While other girls were content to sit and hem a kerchief, Mary escaped to the Bear Garden in Southwark, on the south bank of the Thames, to enjoy the sport of bear baiting and other manly pursuits. ‘Why crouch over the fire with a pack of gossips,’ she apparently asked, ‘when the highway invites you to romance?’

In the summer of 1600, at the age of 15, Mary Frith was charged with stealing 2s 11d from a man in Clerkenwell, snatching a purse from his breast pocket. She was arrested with two other women, Jane Hill and Jane Styles. Two years later, she was arrested again, this time alone, for stealing a purse. Mary was then put on a ship bound for the English colony of Virginia in North America in an attempt to reform her, but she escaped before it set sail and returned to London. Here, she joined a different sort of colony, a nation of land pirates – the cutpurses and pickpockets who haunted the city’s theatres and streets. ‘I could not but foresee the danger,’ she recalled, ‘but was loath to relinquish the profit.’

It was around this time that Mary also became an entertainer, performing inside taverns, alehouses and tobacco shops, as well as on the streets. She dressed in men’s breeches and doublet, held a sword in her hands and accompanied herself on a lute. Crowds gathered to watch, while her pickpocket gang stole the onlookers’ watches and gold.

Mary didn’t just dress in male attire, she was said to have the manner and ways of a man. Her voice and speech were ‘masculine’, she loved to swear and drink ale, and claimed to be the first woman to smoke tobacco. Soon she earned the name Moll (or Mal) Cutpurse – Moll was a nickname for Mary, as well as a common term for a disreputable young woman or prostitute.

Mary’s habit of wearing men’s clothes was regarded by many as a sin. Preachers condemned the practice from the pulpit and quoted from the Old Testament: ‘The woman shall not wear that which pertaineth unto a man, neither shall a man put on a woman’s garment: for all that do so are abomination unto the LORD thy God.’

Dress was carefully regulated in Jacobean England; clothes indicated rank and social class. Only queens and kings, for example, could wear purple silk, gold cloth, or garments trimmed with ermine. Dress also served as a way to ‘to discern betwixt sex and sex’, as Philip Stubbs, a Puritan pamphleteer, explained. Women who violated the rules were ‘monsters of both kinds, half women, half men’. Breeches revealed legs and a crotch, normally hidden by long skirts, and so a woman who dressed like a man was regarded as promiscuous and sexually insatiable.

A young servant in Perth was imprisoned for ‘putting on men’s clothes upon her’, while one London woman was made to stand on the pillory after travelling round the City ‘appareled in man’s attire’. In 1620, two pamphlets were published to address the issue, Hic Mulier: or The Man-Woman, and Haec-Vir: or The Womanish Man. The first criticised women for becoming too masculine – in dress, mood, speech and action – while the second argued that times had changed and so had custom and fashion. If men were dressing up in ruffs and earrings, fans and feathers, then what could women do but ‘gather up those garments you have proudly cast away’?

Some women donned men’s clothes to follow the latest trends, while others used them in order to escape – from a violent marriage, capture or prison. On a practical level, men’s clothes gave more freedom of movement; it was easier to walk, run and ride a horse in breeches than a cumbersome skirt.

Mary Frith appears to have worn men’s attire both to pursue a career as an entertainer and to further her criminal activities. Soon, she attracted the attention of the nation’s playwrights and in 1611, she inspired the central character in Thomas Middleton and Thomas Dekker’s comedy, The Roaring Girl. It was performed at the Fortune Theatre, one of the largest and best-known theatres just outside the City of London. The Roaring Girl was an outlandish figure, a ‘Mad Moll’, a ‘Mistress/Master’, who frequented taverns, mocked the police and was well known in the underworld. But she also provided the moral heart of the play, saving two star-crossed lovers who’d been forbidden to marry.

Moll herself was chaste and swore more than once that she would never marry. ‘A wife, you know, ought to be obedient,’ she explained, ‘but I fear me I am too headstrong to obey, therefore I’ll ne’er go about it.’

In April 1611, Mary Frith herself took to the stage of the Fortune Theatre in an afterpiece to sing, play the flute and banter with the 2,000-strong audience. But although she wore men’s clothes, Mary told the spectators that if any of them thought she was a man they could come to her lodgings where ‘they should finde that she is a woman’. So scandalous was her behaviour – women would not be allowed to perform on the English stage until 1660 – that Mary was arrested and sent to Bridewell, a prison on the banks of the Fleet River.

Not long after her release, however, a showman bet £20 that she wouldn’t ride from Charing Cross to Shoreditch on horseback, in breeches and doublet, boots and spurs. Mary accepted the challenge and added a trumpet and banner as well. She set out from Charing Cross on Marocco, a famous performing animal, and it was only as she reached Bishopsgate that an orange seller recognised her and set up the cry, ‘Mal Cutpurse on horseback!’ Instantly, she was surrounded by a noisy mob ‘hooting and hollowing as if they had been mad’. ‘Come down, thou shame of women!’ they cried. ‘Or we will pull thee down.’ Mary spurred on her horse, managed to reach Shoreditch, and claimed her £20.

But she was soon back in Bridewell again. On Christmas Day 1611, Mary Frith was arrested with ‘her petticoat tucked up about her in the fashion of a man’ and taken to prison. A few days later, she was summoned before the Bishop of London to answer charges of public immorality by wearing ‘undecent and manly apparel’. She confessed to having frequented most of the ‘disorderly & licentious places in this Cittie’ and appearing at the Fortune Theatre ‘in mans apparel & in her boots & with a sword by her side’. She admitted swearing and cursing, associating with ruffians and getting drunk, but she vehemently denied the charges of being a prostitute and pimp who drew ‘other women to lewdnes’. Mary was ‘heartely sory’ for her dissolute life and earnestly promised to ‘carry & behave her selfe ever from hence forwarde honestly soberly & womanly’.

Her punishment came on 9 February 1612. She was made to do penance standing in a white sheet at Paul’s Cross, an open-air pulpit in the grounds of St Paul’s Cathedral, during Sunday service. ‘She wept bitterly and seemed very penitent,’ noted one observer, ‘but it is since doubted she was maudlin drunk.’ Her gang, meanwhile, were busy slashing the clothes of the onlookers, stealing their goods and sending them home half-naked.

By the end of that year, Mary Frith had turned her back on the world of entertainment and in March 1614, she married Lewknor Markham in Southwark. He may have been the son of Gervase Markham, author of The English Huswife, Containing the Inward and Outward Virtues which Ought to Be in a Complete Woman. But it’s unclear if Mary ever lived with her husband. Instead, it appears to have been a marriage of convenience for she kept her legal status as a single woman. As a feme sole, she had the right to own property, make contracts and run a business. But when she was later sued for unpaid bills, Mary claimed the status of a feme covert – a married woman. This meant she was effectively a child with no legal liability for any criminal act; a defence that would be used by female crooks right into the nineteenth century.

Within a few years of her marriage, Mary Frith established herself in a new form of crime by turning her house on Fleet Street into a warehouse for stolen goods. The house stood two doors from the Globe Tavern, a popular watering hole on the north side of Fleet Street, near the corner of Shoe Lane. It became a ‘kind of Brokery’, she explained, for jewels, rings and watches, all of which had been ‘pinched or stolen any manner of way, at never so great distances from any person’. Highwaymen and cutpurses brought in stolen watches and jewellery to sell, while those who’d been robbed came looking for their property. Mary compared her business to the Custom House, with its detailed record of imported goods, and boasted that she had regulated the process of crime by introducing ‘rules and orders’. When a victim came for help, they were questioned about the circumstances of the theft, then Mary circulated a description of the missing item to her ‘agents’. The victim was invited to call back in a day or so, to retrieve their stolen property and pay Mary a finder’s fee.

The business bordered ‘between illicit and convenient’, she admitted, but it provided a better service for victims than the forces of law and order. If a robbery was committed in London one evening, then Mary knew all about it by early the next day – and had a full inventory of what had been taken. Among the stolen goods were gemstones, then arriving in London from all over the world, whether sapphires from India, rubies from Burma, or emeralds from Colombia.

The early seventeenth century was a time of conspicuous consumption, the city’s merchants wore rich, colourful clothes adorned with diamonds, and for a thief there could be easy pickings. Most jewellery, however, was stolen through burglary or housebreaking. In 1590, a well-known gang of women – all called Elizabeth – were found guilty of stealing rings set with rubies and emeralds from houses in north London. All three were found guilty and hanged.

Mary Frith ran her Fleet Street business perfectly openly. It wasn’t until 1691 that a receiver of stolen goods could be prosecuted as an accessory to theft, and only then after the thief had been convicted. She was also a useful contact for the authorities, as she knew all the thieves and cutpurses in London.

In February 1621, a gentleman called Henry Killigrew was robbed one Saturday night, and the very next day he came to Mary’s house, aware that she’d helped many people who’d ‘had their purses cut or goods stolen’. Henry had been propositioned by a ‘nightwalker’ while strolling down Blackhorse Alley, and as he was doing up his trouser buttons, he realised eight pieces of gold were missing from his pockets. The parish constable arrested the suspected thief, Margaret Dell, and took her to the Fleet Street brokery to be cross-examined. When Margaret’s furious husband demanded her release, Mary explained she had a licence to examine and interrogate suspected thieves and advised him to leave before he was beaten up.

But then a farmer was robbed on Shoe Lane and when he came to Mary’s house for help, he spied his own watch hanging in her window. The farmer returned with a constable, and this time Mary Frith was sent to the most feared prison in London, Newgate. She pleaded not guilty, the farmer had made a mistake, it wasn’t his watch at all. When the constable attempted to produce the crucial piece of evidence, the watch had gone, stolen out of his pocket by one of Mary’s thieves. The Lord Mayor was ‘very much incensed at this affront’, and she was warned to behave, ‘which I took very good heed of, resolving to come no more into their Clutches, and to be more reserved and wary in my way and practise’. The jury were forced to acquit her, and Mary Frith went straight back to thieving. Considering she had now been operating as a criminal for some twenty years, her time in prison had been brief, for she had contacts within the judiciary and constables and prison turnkeys ‘retained to my service’.

She made friends with a new sort of thieves, the Heavers, who stole shop books as they lay on a counter, and the Kings Takers, who ran by shops at dusk to ‘catch up any of the Wares or Goods’. Once again, Mary mediated between thief and owner, returning the shop books, which included a record of sales, orders and receipts, to shopkeepers for a fee. She also expanded into forgery, and apparently worked as a pimp, procuring young women for men and, more unusually, male ‘stallions’ for middle-class wives, chosen to ‘satiate their desires’.

Mary was an outlandish criminal, but she was also portrayed as a staunch Royalist who committed ‘many great robberies’ against the Roundheads during the Civil War. When she heard that General Fairfax, their commander-in-chief, was en route to Hounslow Heath, she rode forth to meet him and demanded he stand and deliver. When the general tried to resist, she shot him through the arm and killed two of his horses. Mary was captured and taken once more to Newgate but escaped the gallows after bribing General Fairfax with £2,000.

In the summer of 1644, Mary Frith was released from Bethlem Hospital, better known as Bedlam, although it’s not known why she’d been admitted to an institution for the insane in the first place. After this, she settled down to a contemplative life, reading romances, hiring three maids and ‘intending now at last to play the good House-wife’. She died a wealthy woman on 26 July 1659, aged 74, and was buried in nearby St Bridget’s churchyard, with a marble stone over her grave and an epitaph composed by the great poet John Milton.

St Bridget’s church is just a few minutes’ walk from the site of Mary Frith’s brokery. Today it’s called St Bride’s and its name is spelt out in gold letters above the entrance gate. I sit down on a bench in front of the church, and the noise of the city traffic softens until it sounds like distant waves. On the floor before me are tombstones, but the inscriptions are so faded I can barely read a word. A man appears, wearing a white jacket and a nametag that says ‘verger’, so I stop him and ask, ‘Was Moll Cutpurse buried here?’

The verger looks confused. ‘Who?’

‘Moll Cutpurse, the most famous female criminal of the seventeenth century?’

The verger shakes his head, he hasn’t heard of her.

‘Her real name was Mary Frith,’ I explain. ‘She died in 1659, and she was buried right here at St Bride’s?’

The verger shrugs, lots of people are said to have been buried here, but the Great Fire of London left the church in ruins and so did bombing raids during the Second World War. I ask if anyone has ever come here wanting to see the last resting place of Moll Cutpurse, but the verger gives a final shake of his head and disappears into the church.

Mary Frith’s legend has lived on, however. Not only was she immortalised on stage in the Roaring Girl, but three years after her death, her autobiography was published, and it promised to tell the whole truth about her adventurous life.

I’m standing at a counter in the British Library, waiting to see the world’s only surviving copy of The Life and Death of Mrs. Mary Frith. Commonly Called Mal Cutpurse. Exactly Collected and now Published for the Delight and Recreation of all Merry disposed Persons. I’ve ordered it in advance, and it turns out to be a very small book, only slightly wider than my mobile phone. It has a beautiful chestnut-coloured leather cover and I inspect the scratches on the front, impressed that this is nearly 400 years old. On the spine are the words ‘Life of Mary Frith’ and it seems a little odd that this is the shortened version of the full title.

I sit down at a table and open the book. The paper inside has grown beige with age and feels like cloth, while the pages are so small there is only room for a couple of sentences. It begins with an address ‘To the Reader’, promising a true account of the ‘Oracle of Felony, whose deep diving secrets are offered to the World entire’. There has never been another woman like Moll Cutpurse, the reader is told, and the author hopes there never will. ‘She was like no body … throughout the whole Course of History or Romance.’ Moll Cutpurse was in a category of her own.

I flick through a short biography, until I come to Mary Frith’s own diary. ‘All people do justly owe to the world an account of their Lives passed,’ she begins, entreating her readers to ‘hear me in this my Defence and Apology’. But she quickly changes tack, and for the next 146 pages she relives her ‘Pranks and Feats’ with relish.

The Life and Death of Mrs. Mary Frith is a difficult document to read, and it takes me a while to follow the story. Not only is it written in script that is centuries old, but I’m not clear who is telling this tale. There are times when I think I can hear Mary Frith speaking, when she talks about her friends or beloved pet dogs, but there’s also a more dominant voice, full of literary and Classical allusions.

There are also lots of stories missing from this diary that I’ve read elsewhere as biographical fact. It only begins at around the age of 20, so there is nothing about her childhood, and her age and date of birth appear to be wrong. Mary makes no reference to her groundbreaking performance at the Fortune Theatre in 1611, although she briefly mentions being taken to court for wearing manly apparel. She doesn’t describe any attack on General Fairfax at Hounslow Heath or her admission to Bedlam. And as for her marriage to Lewknor Markham, she doesn’t write about that at all.

At the end of the book, Mary Frith is on her deathbed, offering her penitence and deploring her ‘former course of Life, I had so profanely and wickedly led’. She tells the reader that she has left no will – but she did leave a will, and she wrote it in her married name of Mary Markham.

I close the book and balance it in my hand again. Did Mary Frith actually write this? Did she even know how to write? The introduction says she had been taught to read ‘perfectly’, but that didn’t necessarily mean she could write and, even if she did, would she really have written this on her deathbed? Did she, as some have suggested, dictate the autobiography to someone else? Shakespeare scholar Gustav Ungerer believes that the book was written by a team of male writers, hired by the publishers to capitalise on her fame. If that’s the case, then this ‘diary’ can’t be seen as a credible source, even though it has been repeatedly re-published and quoted from as if Mary wrote it herself.

I go up to the enquiries desk to ask for more details and wait while the woman behind the counter inspects the book. She notes that it was rebound in 1981 by the British Library, so the chestnut leather cover may not be a few hundred years old after all. The British Library catalogue names the author as Mary Frith, yet no one actually knows if she wrote it. Was she really a Royalist, or was this just because her diary was published once the monarchy was back on the throne? Did she ever ride through London on a performing horse? Did Milton write her epitaph? Was she a highway robber at all?

These questions didn’t seem to bother Victorian writers, who plundered freely from Mary’s ‘diary’. Some two centuries after her death, Charles Whibley published A Book of Scoundrels, in which he included just one woman, and that was Moll Cutpurse, ‘the Queen-Regent of Misrule’. Another Victorian writer, Arthur Vincent, also included Mary in his book, Lives of Twelve Bad Women, assuring his readers that he had drawn on ‘the best available resources’ and that his facts were supported by ‘authentic records’. He described Moll as vulgar and brutal, a procuress whose masculine ways made her ‘a pioneer’.

It is as a pioneer that Mary Frith is now being reclaimed and celebrated as a role model for girls. The Museum of London has hosted a talk for children called ‘The Legend of Moll Cutpurse’, while the Wallace Collection featured her in a drama and history workshop for schools. In 2014, when the Royal Shakespeare Company staged a new production of The Roaring Girl, actor Lisa Dillon described Moll Cutpurse as ‘the original girl power, she was a dynamite cool, cool chick’. Others have reclaimed her as a queer icon, and a seventeenth-century ‘gender-bending rogue’.

Images of Mary Frith can still be found in art and museum collections all over London, but as with her biography, it’s difficult to pin down who is being represented and why. The National Portrait Gallery owns ten images of Moll Cutpurse, including a woodcut advertising her appearance on stage in 1611, in which she is a feminine figure with downcast eyes, theatrically dressed in male clothes, with breeches and a large hat. Reference curator Paul Cox has worked at the National Portrait Gallery for two decades, but it’s only in the last few years that people have begun to ask to see the prints of Moll Cutpurse. ‘The requests have increased,’ he says. ‘I put this down to recent academic interest in controversial women from history.’

The Museum of London holds four images of Mary Frith, including an engraved portrait made in the 1660s, in which she has the face of a slightly wizened man, dressed in a long doublet with a wide-brimmed hat on her head. ‘It is a loosely Puritan look and very definitely male attire,’ explains Hazel Forsyth, senior curator of medieval and early modern collections. ‘Men’s garb was easier to move around in and if she was thought of as a man, then that gave her opportunities and flexibility.’

Hazel first came across the portrait in the museum’s print collection while putting together an exhibition on Samuel Pepys. She has since used the image during illustrated talks on seventeenth-century jewel theft, a subject she’s an expert in. ‘People slightly laugh when I show it,’ she says. ‘Generally, they have never heard of her. But her brokery was very clever.’

So what crimes did Moll actually commit? ‘I think she sailed very close to the wind,’ says Hazel, ‘and she was clearly a pickpocket. The fact she wore men’s clothing is not enough to have caused such notoriety on its own.’

But despite Mary Frith’s criminal skills and her longevity in the underworld, her story has always revolved around the clothes she wore and the nature of her gender and sexuality. Was she a woman, a man, neither, or both? In the seventeenth century, she was described as a hermaphrodite in ‘Manner as well as in Habit’, but at her death this was ‘found otherwise’, suggesting her body was subjected to close examination. Victorian writers cast her in a maternal role within her gang of pickpockets and described her as the ‘neatest of housewives’. But she was still a stranger to the ‘soft delights of her sex’, ‘by accident a woman, by habit a man’.

The emphasis on Mary Frith’s sexual life continues today. At London’s Clink Prison Museum, she appears in a small Rogues Gallery just by the exit door, along with Colonel Blood, an ‘improbable rascal’, and Claude Duval, the ‘Dandy Highwayman’. There is no mention of her famous Fleet Street brokerage. Instead, Mary was ‘a brothel keeper, though she seems to have had no interest in sex herself’. An online war-gaming company has produced a miniature ‘Moll Cutpurse – highway robber’, in which she wears a large, feathered hat and breeches and holds both a gun and a sword. She’s also wearing sunglasses and her shirt is half open, revealing a large naked breast. She is designed to be a ‘pin-up’, explain the manufacturers, and is ‘not necessarily historically correct’.

The story of Mary Frith has never been historically correct. She was a performer who took part in her own myth-making; a ‘Queen Regent of Misrule’, who turned the social order on its head. But what do we really know about Mary Frith, and which of her portraits – if any – resemble the real person? She was clearly subversive and went places and did things women weren’t supposed to do, frequenting taverns and appearing on stage. But while she may have apologised to the Bishop of London for her dissolute life and offered her penitence in her deathbed diary, she doesn’t appear to have been that repentant. She was an outlaw who revelled in breaking criminal law and in breaking society’s laws. But her ‘masculine ways’ have overshadowed any detailed analysis of her criminal career, and even today she’s better known for wearing breeches than for her Fleet Street brokery.

Mary Frith seems to have worked independently as a criminal, running her own business and operating in a world largely dominated by men, whether thieves, victims or constables. But another Queen of the Underworld, who was based just half a mile north of Fleet Street, would take another approach. Unlike Mary, she worked closely with a small gang of women – and their targets were specifically men.

2

ANN DUCK: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY STREET ROBBER

One snowy December evening in 1743 two young women were walking up Snow Hill, just west of the bustling Smithfield Market in the City of London, when they met a gentleman out for a stroll. ‘My Dear,’ said Ann Duck, ‘it is a very cold Night, suppose you, this young Woman and I, were to go to a House, I know you will be so good as to give us a Dram this cold Evening.’ The gentleman agreed, and off he went with Ann Duck and her companion Ann Barefoot to a pub near Chick Lane, one of the most disreputable streets in eighteenth-century London.

The landlady showed them up the stairs. A bowl of punch was called for and then another. The man began to be ‘very rude’ towards Ann Barefoot – ignoring her friend because he didn’t like her ‘tawny Complexion’ – and she took affront at the gentleman’s behaviour. Did he think they were ‘Women of the Town’? If he did, then he was very much mistaken, for both were married and had very good husbands. They had never in their lives gone into a house with a strange man, and he should ‘take it as a particular Favour’.

At this point, the landlady returned with a fresh bowl of punch, drank a glass to the man’s good health and assured him that Ann Duck and Ann Barefoot were ‘as modest Girls as any in London’. With the punch finished, the man began to be very merry indeed and the ‘modest girls’ got down to business. Ann Duck threw him on the bed and held him down with all her strength, while Ann Barefoot picked his pocket, taking his watch and 22s in silver.

Then Ann Duck gave her usual signal – a knock of the foot – and up came one of her bullies or ‘husbands’. Bullies were ‘lewd, blustering fellows’, explained one guide to London criminals. ‘Their rendezvous is among bawds and whores, they eat their bread, and fight their battles.’ But while the men may have received a share of the spoils, they were hired accomplices rather than pimps.

The bully swore at the gentleman who’d been robbed by Ann Duck, and asked ‘what Business he had there, in Company with his Wife’, at which the victim took fright and ran down the stairs crying, ‘Thieves! Murder! I am robb’d of my Watch and Money!’

Later that night, the gentleman returned with a constable and Ann Duck was carried to the local Watch House, where suspected offenders were questioned and held overnight. She was then sent to Newgate to await trial, but ‘was so fortunate … to be acquitted’.

Fortune did seem to smile on Ann Duck when it came to being acquitted. But then she was a member of the Black Boy Alley Gang, one of the most fearsome groups of street criminals in the capital. Over one week in August 1744, the gang attacked and robbed dozens of men, making ‘a noise like a parcel of ravening wolves’. When one gang member was captured and taken to the Watch House, the others broke in and rescued him, firing pistols at neighbours who were shouting ‘Murder! Murder!’ from their windows.

The press seemed intent on fuelling a moral panic about street violence, portraying the gang as insolent and barbarous, committing crimes day and night, in contempt and defiance of the law.

The Black Boy Alley Gang numbered around twenty to thirty men and boys, and their captain appeared to be 19-year-old Richard Lee, known as Country Dick, a little fellow with ‘a bold and daring Spirit’. Other men included Thomas Wells, a lamplighter whom Ann Barefoot described as her husband. There were at least nine women in the gang, who were sometimes known as the Black Boy Alley Ladies, and they either led street robbery attacks or fenced the stolen goods. Many of the women were called Ann – one of the most popular female names of the time – and Ann Duck had the worst reputation of all. The young woman with a ‘tawney’ brown complexion would be arrested – and acquitted – nineteen times for theft, assault and highway robbery. She was one of the most notorious street robbers in London, and her base was Black Boy Alley.