10,04 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Fair Play Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

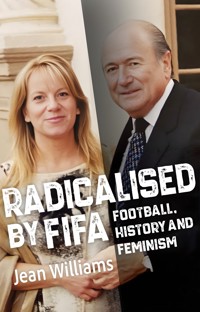

What do a childhood on a remote farm, a career in academia, and the corrupt underbelly of global football have in common? In Radicalised by FIFA – Football, History and Feminism, Professor Jean Williams weaves them together with sharp humour and political bite.

Part memoir, part cultural critique, Radicalised by FIFA explores how a love of football—and outrage at its inequalities—sparked a lifelong campaign for justice both on and off the pitch. From muddy grassroots fields to the politics of the Women’s World Cup, Jean exposes the systemic barriers facing women in sport and in life.

With themes of gender, power, institutional hypocrisy, and the personal toll of pushing against entrenched systems, Radicalised by FIFA is essential reading for anyone who believes in the transformative potential of sport—and the need to reform it.

The memoir also covers the impact of global events like the SARS and COVID pandemics and September 11, alongside the rise of social media and the fight for equal pay in women's football.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 509

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

RADICALISEDBY FIFA

FOOTBALL, HISTORY AND FEMINISM

RADICALISEDBY FIFA

FOOTBALL, HISTORY AND FEMINISM

Jean Williams

First published in 2025 by Fair Play Publishing

PO Box 4101, Balgowlah Heights, NSW 2093, Australia

www.fairplaypublishing.com.au

ISBN: 978-1-923236-05-9

ISBN: 978-1-923236-06-6 (ePub)

© Jean Williams 2025

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the Australian Copyright Act 1968(for example, a fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review), no partof this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, communicated ortransmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission from the Publisher.

Design and typesetting by Leslie Priestley

Front cover photograph of Jean Williams and Sepp Blatter in 1999 by Simon WilliamsBack cover photograph of Jean Williams at the 2023 World Cup in Brisbane by AlamyAll other photographs supplied by the author.

All inquiries should be made to the Publisher via [email protected]

A catalogue record of this book is available from the National Library of Australia.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Feminist

CHAPTER I: THE BARBIE WORLD CUP, 1999

Introduction: Thriller in Windhoek

Jeanola and Simone in LA

Conclusion: The Football Mothership Calling me Home

CHAPTER II: THE HANGOVER WORLD CUP, 2003

Introduction: Falling

The SARS Pandemic Disrupts Women’s World Cup 2003

Conclusion: Falling for Marta

CHAPTER III: THE INVISIBLE WORLD CUP, 2007

Introduction: Lunch with Sir Bobby and Sepp Blatter

Marta’s World Cup

Conclusion: The unseen GOAT and disappeared women players

CHAPTER IV: THE ´TIE IT UP WITH A BOW AND GIFT IT´ WORLD CUP, 2011

Introduction: Free Lunch

Karla Kick, and Germany 2011

London 2012: The Second Austerity Olympics

Brittle Academic Masculinity

Defying Clarity

CHAPTER V: THE ARTIFICIAL WORLD CUP, 2015

Jacqui and the Chocolate Factory

Not Staying in My Lane

Grass is a Gas in Canada 2015

CHAPTER VI: THE WAGE THEFT WORLD CUP, 2019

Storied Objects

Chicks’ Football France 2019

Different But Equal?

CHAPTER VII: THE INDUSTRIAL DISPUTE WORLD CUP, AUSTRALIA, 2023

The Night Soilman’s Granddaughter

A Kiss is Just a Kiss: Australia 2023

Dedication

For Simon, always and forever.

With thanks

Mum and Dad, thank you. Apologies for theswearing and the name-dropping.J, K and L, thanks for your comments onthe early drafts.

In memory

In celebration of the revolutionarygenerosity of Grant Wahl.

PROLOGUE

Feminist

Growing up on a farm, I had seen a lot of sex, birth and death by the time I was nine. The mating animals were ‘fighting’, we children were told. Probably not the best preparation for a lifetime of balanced adult intimacy, but I have been happily married for 38 years at the time of writing, so I must have negotiated this particular maze OK at some point. The births were miraculous and messy, as is life. The deaths were unbelievably sad and final. Watching that spark leave the eye. I still prefer animals to human beings. Not you, of course. You are unique and wonderful. Do tell your friends about this book. But I am probably going to greet your dog before I notice you. For which, my apologies in advance. Your best friend, however, understands entirely. I loved spending my quiet time in childhood leaning against a ruminating cow, draped over a sleepy horse or nose to snout observing a piglet’s complicated facial expression. Home is standing in a Leicestershire field, this heart-shaped county in the centre of England.

Mischief and mayhem came naturally. Still do. The local refuse collectors, aka ´bin men´, were in accordance that my rendition of Sandy Shaw’s 1967 Eurovision-winning ´Puppet on a String´, complete with barefoot dance moves and an encore, was a triumph, if lacking any musicality. By way of rehabilitation, aged three, off I was sent to Mrs Dunbar’s Academy for Young Ladies and Gentlemen. I went three times a week. Singing ´Puff the Magic Dragon´ in the car with my Dad or my Mum on the journey to and fro, I made up for in volume what I lacked in accuracy. Dad always had a nice car, most memorably a burgundy Daimler, and Mum drove a sporty banana yellow Escort MK 2.

The daily sticking point on arrival was that I liked the colour orange, and Mrs Dunbar had decided that the towels for girls in the bathroom should be lemon yellow. She was clearly influenced by the nursery rhyme, ‘Orange and Lemons say the Bells of St Clements’ which we sang most days. Saint Clements-style, our towels were arranged in alphabetical order, boy-girl, orange and yellow. The boy before me was called Ian, so he had an orange towel; and the boy after me, Justin, did too. I just could not understand this illogical system where I got a yellow towel. So… I’d swap the towels. Every day.

Mrs Dunbar was keenly aware that I was a forceful child. It may have been a coping strategy as I am from a large family, but it could just have been my personality. The other Academy children had an hour´s nap after lunch. This mystified me as being a complete waste of time. When Mrs Dunbar invited me to sleep after lunch, I replied that I’d rather keep her company. I suspected she would have preferred to nap herself, but instead we made cakes and I chatted to her in what I imagined was a companionable way. I could see that her facial expression was a little tired sometimes. She once kindly asked, would I like a little cookie dough from the bowl. I was offended as I had never heard of this abomination. ‘No thanks, Mrs Dunbar I’d sooner wait until the cake is baked, like at home.’

The Dunbar Academy Christmas party was worse. We were each given a toy to take home about an hour before the party ended. Instinctively I could tell Justin would not like his—the shiny red sportscar, but I loved it. Instead of the car, Justin coveted a fashion book I was given, where the cardboard girl models could be dressed in paper mix and match items to make a full outfit. The clothes were pressed out of the book and fitted onto the dolls with little paper tabs at the back. Justin and I swapped toys and played happily until it was time to go home, when we were made to swap back again. The fate of the car remains a mystery, but my paper dolls lay unloved until they were used as kindling to light the coal fire at home.

Mrs Dunbar seemed relieved when I started school aged five, and baked me a cake to send me off. I still remember the little white picket fence of her house with great affection. It was rumoured she retired soon after and returned to the Highlands and Islands. Some folks said she went as far as the Isle of Skye. No forwarding address was ever forthcoming.

Infant school was a pointless blur of sticking, colouring and singing. Frankly, the other children seemed too easily distracted by playing house, making fuzzy felt pictures and other nonsense. I had that dreadful realisation at the end of Week One that I would have to go back. The horror! As someone who was down the farm by 6.30am each morning, I would reluctantly have my day interrupted to go to breakfast and then school about 8am, and then waited impatiently every day for three in the afternoon so I could return to the animals. Summer holidays were bliss! September still fills me with dread.

Potato picking in the freezing October rain of 1970s Britain instilled in me my first feminist sensibility. The middle child of five, ‘Being Useful’ on the farm was important. I prized icy tubers from mud so heavy with clay that it sometimes retained my wellie boot, and hurled them into the wire basket before dragging it to the sack where one of the men would lift and return it to me. And on, and on, and on. A wet sock, a dribbling nose, hands with hot-aches, toes with chilblains, and a soaked anorak were the main rewards, along with the potatoes. I knew, even then, that people who were nostalgic about the nobility of unskilled manual labour probably didn’t have to do much of it. Now, I am not pretending for a moment that, aged nine, I did a 37-hour working week. But I did do every day of the October half term for several hours, helped by sweets from neighbours, and the camaraderie of a joint task.

Until I went to university in 1982, October half term holidays consisted of brown mud, grey mist, and potatoes. At least on Thursdays there was Top of the Pops. Fridays there was the cheery children’s programme on TV at five minutes to five called Crackerjack! As soon as I was in charge of my own destiny, I endeavoured to spend October half terms somewhere sunny, where the only potatoes I encountered had already metamorphosed into golden chips.

The feminist education came courtesy of assumptions about men’s and women’s work that saw my elder brother Michael, by then almost 18, not actually collecting the spuds but driving the tractor. Although he was my childhood hero, Michael found many creative ways to torture us. Glorying in being in a warm cab, with the radio on, a place for both the farm dog and hot coffee, Michael would gurn as he passed us with the ‘tater device on the back of the David Brown. His tractor-work theoretically raised the King Edwards to the surface for our collection, but in icy ground this was only partially successful. Once bagged, the sacks of potatoes would be collected on the back of a trailer pulled by a Massey Ferguson. So, there was a lot of driving to do, and also a lot of opportunity for him to warm up in the sheds out of sight of the frozen souls in the field.

Michael was in absentia too often for my liking. At the end of the week, we children were each given 50p. Pretty good wages and probably worth the equivalent of £15 pounds now. But Michael got £5. It was plain economics so far as I was concerned, ignoring the age difference.

I resolved then and there to be the one who drove the tractor.

I soon got my wish and was steering the Land Rover around fields. This had begun about age 10 when Uncle Ted, who lived on the farm, would put the vehicle in a crawler gear, and get out, walking just behind the door so I couldn’t see him in the mirrors. About 100 metres from a hedge, I’d shout— ‘Ted, Ted we’re going to crash!’ and he would open the door, laughing, hop in and turn the wheel. Eventually, I could steer around corners, and Ted could stand on the tailgate at the back to throw feed to the animals who followed the truck. Not strictly legal, but very empowering. More perilously, Uncle Ron would tow us on sleds behind tractors, weaving around to try and throw us off into the snow. But we became very self-reliant. There were all kinds of kit to drive on the farm, with tractors legal on the fields, but not the roads, from age 13.

My friend June and I used to drive a Mini around fields on Sunday afternoons, using goats as slalom posts until one occasion when she failed to break in time and nudged a dozing animal over. The billy goat was more offended than hurt. He went on to live a very long life. I can assure you that no goats have been harmed in the writing of this book. I still love to drive, and would love a pale lavender Porsche Targa with colour coded ceramic brakes if this memoir takes off, so have tried really, really hard to make it good. As I said, it would make a great gift for your many, many friends!

Youth, and being young, were very politicised during the whole of the 1970s. Youth unemployment ran rife after the 1973 oil crisis, with yacht-owner and Prime Minister Ted Heath unsympathetic to families. I distinctly remember my Mum making complex dinners in the evenings followed by family board games during the power cuts in 1972 when the lights were off for nine hours at a time. The scale of the miners’ strike which occasioned the electricity rationing, was the first such widespread industrial action for 50 years. In 1974 during the three-day working week Mum was cooking by candlelight on a Gaz-powered camping stove for seven people, and after with no television, we read books by candlelight. At least on a farm we had ‘red’ diesel with which to run generators, but fuel prices soared. The three-day week lasted for two months during January and February, meaning my tenth birthday was a very frugal affair.

Growing up in the 1970s was like that iconic chocolate brown Admiral football shirt design for Coventry City, with two thin vertical rails of white. There was 90% hard grind and 10% celestial hope.

Three things saved me: in chronological order they were reading, David Bowie, and Simon. My first big book I read on my own, aged 8, was Treasure Island, a pretty good one to start off. By the age of ten I had read all of the books in the village library and had moved on to Hinckley where I got my first identity badge, a library card, which entitled me to ten, TEN, books a week. What an absolute luxury! The library was warm, well-lit, quiet and stuffed with ideas. I loved it. Since this book is jam packed, (and consequently very good value) I am not going to go off on a tangent here about David Bowie who arrived in the drab 1970s in glorious technicolour with his arm around Hull’s silver-haired Mick Ronson, so will save that for another project. Simon is just about to stroll in to make his entrance in a few pages.

Moving on to Barwell Junior School, my next significant memory as to my feminist education came aged 12. A great friend, Annette Astley, was a sporting all-rounder, and academic to boot. Annette was the leading striker for the school football team, until a ruling came down which I later learned was the Theresa Bennett case, which prevented girls at the age of 12 playing on a team with boys. This included school teams. More mature and faster than most boys her age, I had a sense of injustice that she was clearly discriminated against for being a girl. Annette excelled at many other sports and went on to study at Loughborough University where she picked up her football again. Years later this sense of being perplexed, when Annette was clearly the best player, would pop up out of my subconscious and motivate me to write a PhD. And then some…

I wasn’t personally outraged, because my football was mainly social, and by then my chief pastime was a very old hand-me-down pony called Rocket upon whom I’d amble around. He was a wily old trooper. He would breathe out while I’d cinch up his saddle, then breathe in again when it was on to give himself plenty of breathing space. I’d have to be very determined to get him into the field, intending to jump hurdles, before he would get to the gate, turn of his own accord and Usain Bolt it back again, direct to the stable. If he got winded on his return, he’d lean up against a telegraph pole, making sure to crush my leg with his full body weight, to remind me not to kick him in future. Adoration was not even close to how much I loved him.

Being a farm kid, by the age of 14 the bullying on the school bus was so bad I would often prefer to walk the two miles home from Earl Shilton Community College— whatever the time of the year. This was risky. Both the short-cut through the park, and the last mile home were entirely unlit. Even with a torch, the lack of streetlighting left an all-enveloping blackness in October, November, December, January and February. So, some bleak winter nights the battle of the bus had to be borne. To avert my dread of two boys in particular, I would usually read books from the school library.

The boys in question, Big Kev and Jeffrey, would grab my school bag, take it to the back of the bus and empty it at the start of the journey. Jeffrey was in my year, sly and spiteful; Big Kev in the year above and about 13 stone. I was less than five foot tall and six stone wet through. I knew Big Kev’s Mum was religious and ruled him with a rod of iron, literally. So, I understood he was clearly taking this out on someone else. Essentially a biddable bear. But Jeffrey delighted in tormenting others cruelly. He would wait to assault me as soon as we left the school gates, to avoid being reported, and encourage Big Kev to restrain me while he ceremoniously tipped up the bag. I was determined not to give them the bag voluntarily in spite of the consequences.

In what became a regular social contract understood by everyone on the bus, all my stuff would be kicked up and down the aisles for the entire journey by the other kids, who realised that as long as they participated in that game, they wouldn’t be the object of bullying themselves. The driver was impervious, as he was just doing his job until the shift was over. Since my house was half a mile before the final destination in the next village, I would have to wait until everyone else got off at the last stop, pick up my stuff, say a wordless goodnight to the driver who sat with averted eyes, and walk home half a mile in the dark. My little brother was also on the bus, and while they were picking on me, they weren’t hassling him. Well, quite so much anyway.

So, I didn’t like the bus, and there was also the matter of the friendless half-hour wait between the end of the school day and the bus journey. Boredom. However, the school library was quiet, well lit and warm. So the obvious thing to do was to look for mucky books. I had already located Lady Chatterley’s Lover in the school library knowing it had been banned until recently. But I was buggered if I could figure out what act Mellors had performed in the potting shed. James Joyce’s Ulysses was frankly too little reward in titillation for too many pages of reading. There was more violence in A Clockwork Orange than I could stomach for very long, so no luck there.

Then, bingo, I located a book with a twisted woman’s torso on the cover! Headless, legless and armless. Brilliant. Probably a ghoulish murder mystery, I thought. I began reading the chapter entitled ´Sex´ and encountered my first clitoris, (albeit in writing). Thrilling. As I read on, the ´See You Next Tuesday´ word was used! Shocking. Then I was advised to revolt against male-dominated systems. Had the author, physically or metaphorically, been on the same school bus as me, perhaps?

The book I had discovered was The Female Eunuch published in 1970 by Australian feminist author Germaine Greer. The book was so topical because in Britain the Sex Discrimination Act would follow five years later. Getting a mortgage as a single woman usually meant getting your father’s permission. Married women usually had to get their husband’s permission to obtain birth control. In her many years since 1970, Greer has become something of an outlier to the feminist canon, but this library find was pretty revolutionary stuff for a 14-year-old in rural Leicestershire. It may seem like a joke—in search of a mucky book I found feminism, but language was key to what is now called ´the second wave of the women’s movement´, and Greer epitomised that demystifying impulse.

And the bus journeys? I was literally saved by the patriarchy in the shape of my dear pater. One day, after about a year of this, my Dad, to my immense surprise and good cheer, boarded the bus after flagging down the driver outside our house. Dad had some very choice words for the driver, Big Kev and Jeffrey. Hero. Big Kev and Jeffrey were instructed to pick up my stuff. Dad told the driver that, as an adult he should know better and that he had a duty of care to the children on the bus. This had never occurred to me, moderate violence and verbal abuse being so much part of our daily lives at school. I have never allowed myself to be bullied again. The last I heard, Jeffrey had become a ‘holier than thou’ minister of the cloth in some obscure Christian enclave, and Big Kev was cleaning chemical toilets on building sites. Nearer my God to thee, indeed.

Having survived all this to obtain five O levels, in the Sixth Form my subjects narrowed to A Level English (by far my favourite), Sociology (it was new), and very reluctantly History (my teachers managed to make both Catherine and Peter the Great seem distinctly mediocre). Sociology was taught by a vibrant, committed young woman, and an older female teacher borrowed from Business Studies who, given her surname, we predictably nicknamed Granny Smith. I made some remark about gender to the younger teacher, and she suggested that she and I organise an event for International Women’s Day, which I hadn’t heard of before. I had however been to Young Farmers´ Annual Harvest Festival and had carved a pineapple into an owl with maraschino cherries for eyes in the ‘I Made it Myself Competition’ to win third prize. Why not give it a go, I thought?

My expectations were that we would do some things at which men were naturally good. A game of darts perhaps? Woodwork? And some basic car maintenance? You can imagine how much my consciousness was raised when I arrived to find women breastfeeding in public, wearing Lesbian Mothers Against the Bomb t-shirts.

This was in the 1979–80 school year, when various women’s groups were becoming more militant. Often generalised under the term ´Second Wave Feminism´, this would culminate in the UK with events at Greenham Common in September 1981, when 36 women chained themselves to the base fence in protest at nuclear weapons. In 1982, 30,000 women linked hands around Greenham in the ´Embrace the Base´ protest, and in 1983 this more than doubled to 70,000. One Greenham protest saw 200 women dressed as teddy bears breaking through the fence.

Greenham was a reminder of how bitterly contested gender relations were just as Britain was about to endure its first female Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, who came to power in 1979. A woman who hated miners, teachers, and football crowds—in fact any kind of collective action, Thatcher would preach individualism. She envisaged a nuclear family, owning its own home, with a few entrepreneurial shares on the side. Shame that when she sold off many of the publicly owned utilities in a process called privatisation, they were bought by multinational businesses, rather than the little gal and guy. This happened particularly in the energy and utilities sectors. In the UK we are living with the consequences of privatisation of our natural resources still today, with water pollution levels rising unsustainably and a cost of living crisis. Generally, Thatcher blamed feckless youth rather than the global geopolitical situation, rising inflation and industrial unrest. I would not see such wilful insularity and ignorance again until the Brexit referendum.

Punk rock was the do-it-yourself response to the dire economic situation in the 1970s, both in fashion and music, and I was drawn to its powerful rejection of tradition. You could just literally make stuff up! Put a safety pin through your ear. Make a dustbin bag into a dress. Dye your hair with fabric tints. Whatever. There were also important precursors to the football fanzine movement linked to Oxbridge student satirical writing, such as Foul. Punk was a very creative response to a lack of hope widely felt by young people. I thought Vivienne Westwood was amazing, and dyed my hair pink like Zandra Rhodes.

About this time, I met a very handsome 19-year-old biker who told me he was in a punk band called The Screaming Knees, and reader, I married him. Given how often Simon was involved in accidents, I came to understand why his knees might scream. Simon’s motor sport heroes either won or crashed, preferably both. My future husband was much the same. On one occasion, I knew he had been in a collision because he was half an hour late. Simon is always 15 minutes early. He later told me he slid on his knees down the road to avoid a worse collision, only to smash out the car’s rear lights with his head. I’ve learned a lot about resilience from Simon. He wasn’t actually registered as a student at Loughborough University but was there so regularly while I studied English that everyone assumed he was. He often fixed the motorbikes of the Engineering students for whom practical work was perplexing. After university, with a decent 2.1 in English I asked my tutor about doing an MA, but he explained kindly that Masters degrees were really meant for people who had obtained a First, of whom there were only two in our cohort of English graduates. I began packing Care Bears, Ken dolls and Barbies at Mattel Toys soon after.

After university Simon and I married on FA Cup Final day 1986 at Hinckley Registry Office at 11am. A few photos, a nice lunch, some speeches, then back to Mum and Dad’s to watch the match as it was a 3pm kick-off at a capacity-packed Wembley. A Merseyside derby between Liverpool and Everton, the match saw Gary Lineker score the only goal for the Blues in the first half, before the Reds came back, courtesy of two goals from Ian Rush and one from Craig Johnston in the second. Dramatic for a big game, the FA Cup completed the double for player-manager Kenny Dalgleish as Liverpool had already won the league.

Some of Simon’s more refined relatives had assumed we had married in a Registry Office because of their Jehovah’s Witness beliefs. They chose to remain in the dining room drinking tea and eating cake, while my family were just relieved not to miss the football. We resumed festivities dancing to the Shalako disco at 6pm, and honeymooned in York for four days. The Railway Museum was thankfully free to enter because we had a 101% mortgage, and could not afford the fees to purchase the house, let alone nice things like meals and days out. This was the Eighties, remember, and greed was good, so you could borrow more on a mortgage than your house was worth. What a great idea that turned out to be. Within two years we were paying 15% interest on our borrowing for the mortgage.

There followed a period of mutual adjustment, as I was only 22 and Simon was 26 when we married. Going to a supermarket on our return from honeymoon, I invited Simon to get whatever he fancied, meaning quite clearly to pick something he wanted to eat for the evening meal. He returned with a £20 trolley-jack for the car, and enquired as to what we were going to have for dinner. Dull it was not!

After a brief stint as a shoe buyer’s assistant, and other desultory work, I trained as a teacher of English and taught in a Sixth Form College in Leicester, one of the most diverse cities in the UK. The Iron Lady would be deposed in 1990, largely thanks to her antipathy to Europe, which even Home Secretary Sir Geoffrey Howe could not disguise.

My students in the Sixth Form College taught me more than I was able to educate them. I kept telling anyone who would listen that Toni Morrison was our greatest living writer. But while I waffled on about Carol Ann Duffy, the use of irony in Shakespeare, and Caryl Churchill, they told me about their lives. The quiet pale girl at the back who rarely said anything but exploded in class the week of the Grand National because she hated gambling since her father was an addict. I was known in my pastoral role for also welcoming the goths, who would arrive in basques (Victorian-era closely fitted bodices), fishnet stockings, and thigh-high boots but who were intensely shy. A young Chinese woman in my tutor group had to do extra work in the takeaway to come to class, with hopes of getting her A levels, going to university, and never having to listen to the levels of casual racism that her parents endured in the course of their work. I tutored students who were becoming aware of their sexuality, and negotiating the consequences of what that would mean for parental expectations.

This was a big deal in education for over two decades. In 1988, Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government enacted Section 28 (sometimes referred to as Clause 28) to ‘prohibit the promotion of homosexuality by local authorities’ including schools. Shockingly, it would remain law until 2003. I remain very proud of my work with the sixth form students, ignoring Section 28 by showing films like Hanif Kureishi’s 1985 romantic comedy My Beautiful Launderette in film club, and teaching books like Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit in the curriculum. Education should be about helping the individual to reach their full potential. If they can’t talk about who they are, how can we expect to help?

All my students were trying to use education to improve their lives in both small and large ways. There wasn’t much career progression available then for young women, especially as head of department. But I was influenced by a colleague to have another tilt at an MA, this time a part-time mode of learning, in Modern Literary Theory and Practice. It was tough to study part-time and teach full-time. A technician employed to assist the students helped me in her breaks to learn to type and use a computer. My MA thesis was on Toni Morrision. The day it was due, during the school holidays, the floppy disk (look it up) on the computer I was using got full and I lost about half my work. I had to get an extension and re-type it, crying with tiredness and frustration.

When I had completed university as an undergraduate only five years earlier, and my teaching qualification, the PGCE a year earlier, all our essays were hand-written. The whole thing was a steep learning curve. I won’t pretend the thesis was terribly original—or well done, but the fact that it was done at all when holding down a full-time job showed me how much I loved research and academic writing.

A few years later, in 1994 the owner of a wine bar and bistro that Simon and I frequented early doors most Sundays, offered us the licence. Having bought it, we couldn’t even use the till at the opening night and had to give the drinks away for free. My Mum was a superb cook, as I have mentioned. Her three-course Christmas day lunch on the farm was often for at least 20 people, including some waifs and strays, sitting on odd chairs that I only saw once a year. Eat turkey while sitting in a deckchair indoors? Everyone welcome! Through her tutoring, I did most of the catering in the bar, and we made a go of the new business. In order to juggle two jobs I went part-time at the Sixth Form College Monday to Wednesday lunchtime, then did all the cooking and food prep from Wednesday evenings to Sunday.

Exhausted, the chance to take voluntary redundancy from teaching came in 1997, and I took it, spending half the money on a week at the Hacienda in Ibiza, and half on my first personal computer. Regrets, I have a few. Had I the chance again I’d have spent two weeks at the Hacienda where I hung out in the pool each morning with a Russian escort who had cheek bones sharper than my grandmother’s tongue and seemed about eight feet tall even when she was reclining in the water. While her impressive frame was bedecked in a seemingly endless succession of designer swimwear, I had splashed out £25 of my redundancy on a Marks and Spencer leopard print bikini for the week. The Hacienda was the first high end hotel where I’d seen a pool in the brochure and decided to stay there 75% motivated by swimming. I’d go on to ‘collect’ other such experiences over the years. With its cliff-top position, the scintillation of the light on water was stunning by day, and even more atmospheric at night due to the low levels of light pollution - like swimming in a galaxy of endless stars.

I had been told at school I had working class legs, which meant that the length of my shin was shorter than the thigh bone, whereas apparently posh people can afford to have similarly long femur and tibia. Trust me, there are serious medical articles that deduce ‘Leg length and proportion are important in the perception of human beauty, which is often considered a sign of health and fertility.’ My Russian friend had definitely got the aristocratic equally proportioned long-legged memo, whereas my disappointing evolutionary stumps were showcased in high street leopard print. I could make her laugh though, sometimes intentionally, and I think did win bonus points for being a game chicken. Having said all that, two weeks at the Hacienda would possibly have made future employment a moot point. So buying a home computer definitely prolonged my life, even if it didn’t necessarily make it more interesting.

At the same time, I obtained a 0.7 job (three and a half days a week) at De Montfort University. This was as a Professional Skills Tutor for a Combined Honours degree. Those students who did not have quite good enough grades to get onto a Joint Honours degree of two subjects, took three subjects in their first year and Professional Skills Training. Hence Combined Studies. Then, they would choose a conventional Joint Honours combination of two subjects for the remaining two years. It was a huge success! We recruited upwards of 450 students per year and many students who couldn’t have made it into higher education became the first people in their family to complete a degree.

This meant that Combined Studies as a unit was very well off financially, and this in turn meant that Deans of Faculties were jealous that they had not thought of the idea. It also meant that when I was told that to work at a University I would need to study for a PhD, I was able to do so, because my part-time fees were paid by my employer for the first two years. And when I asked the Combined Studies course leader to use my entire continuing professional development budget to go to the Second World Women in Sport Conference in Namibia in 1998, he was very supportive, having studied for some time in Africa himself.

A brilliant negotiator with the Senior Management team, he even supported my staying in the best possible accommodation, which is why I was in the only 4* hotel in Windhoek in May 1998. Working three and a half days a week at the university, owning and cooking for the bistro, I was by now collecting data for my PhD in my free time, when not actually playing football, I was serving on the East Midlands Women’s Football League committee, starting my coaching journey, and attending women in sport conferences.

I had thought I was going to be a Toni Morrison scholar but I didn’t find the English department at De Montfort particularly welcoming. There had been a new specialist research centre set up in the history of sport in the 1996/7 academic year, and I had thought to combine the literature and history of football there. So, one day I wandered into Professor Wray Vamplew’s office and muttered something about wanting to do a PhD. Wray had lots of mugs with sporting themes on his shelves. He’d recently returned from Australia having been a Pro Vice Chancellor at Flinders University and had begun to work at De Montfort in 1993, later establising the International Centre in Sports History and Culture as a way of developing the research culture of what had been Leicester Polytechnic, and so more used to vocational education. He was friendly, open to ideas, and kind. We agreed I’d fill in the paperwork. Then in 1998 we refined the PhD proposal to be about the history of women’s football.

My parents were puzzled that anyone could do such a thing, although very supportive of this as in everything else. As the first person in my family to go to university, I had not a clue how to go about doing a PhD. I did have the additional superpower of Simon though. In spite of having two jobs, he would drive me up and down the country on Saturday afternoons to interview women with collections of women’s football memorabilia, with my first giant, 2 kilo laptop computer I owned, and a scanning machine we plugged into it to copy materials, photographs and scrapbook images.

This joint venture, like many of our other collaborations, would take us both to many new and unforeseen places. Everyone should have a Simon.

CHAPTER I THE BARBIE WORLD CUP, 1999

Introduction: Thriller in Windhoek

I was excited and nervous leaving the hotel room in Windhoek, Namibia in May 1998, on my way to give my first academic paper at an international conference, only to be confronted by a human rhomboid filling the entire doorframe. Surveying the blockage, I spied an expensive black suit jacket, several ripples of neck fat above a white shirt collar, and what I deduced to be an earpiece on a little corkscrew of white wire. The actual earpiece, like my view, was obscured completely. A voice said, ‘Please step back inside Ma’am and close the door.’ It took a few seconds to figure out the diamond-shaped gentleman was addressing me.

‘Get out of my way please,’ I remonstrated, ‘I am giving a paper at a women and sport conference in about 10 minutes downstairs. I cannot be late.’ In the same even voice identical instructions were repeated to me, like a call and response in an old song. How dare a human lozenge invade my personal space with his considerable rear! I’d flown out specially. Our voices became raised whispers (although I have no idea why we were sotto voce), and eventually became hisses. I ain’t going nowhere, but I’m not going anywhere any time soon, I sense.

Finally, there’s a kerfuffle to the right of me which distracts us both. A whoosh of air, lots of people talking all at once, and an atmosphere of organised chaos, or perhaps choreographed panic, making its way towards us. My adversary’s final instruction is emphatic, ‘Ma’am, please close the door and do not come out, Michael is walking the corridor.’ But the directive was too late. Michael is walking the corridor. As I peep on tiptoes under the bodyguard’s armpit, I can see lots of hangers on, all dressed in black doing stuff in a fairly frantic but precise way to the main man. A grasping woman primps his hair, although he is wearing a hat; an anguished-looking man reads out a schedule for the next hour; there is lighting, a sound recordist, lots of security detail.

As he passes my door at some speed Michael Jackson looks into my eyes, as if surprised that one of his bodyguards should have a woman’s head peering from underneath his arm. He is frightened. I was oddly reminded of the scene in the 1942 Disney movie Bambi, where the anthropomorphised rabbit helps the baby fawn to learn to ice skate before declaring ‘Kinda wobbly, aren’tcha?’ When I almost met Michael Jackson, in that fraction of a second, he was distinctly off-kilter.

I later learned that MJ was in Windhoek in 1998 to launch a new Neverland ranch theme park to aid tourism to Namibia. Well-meaning but ill-advised. After conflict and struggle for independence from German, British and then South African control throughout the 20th century, at that time Namibia was politically, economically and socially the youngest African country. Whether the idea of a Neverland ranch was intended to bring in international tourists, or even if there was a coherent strategy remains unclear, as the accusations against Jackson for child abuse, financial difficulties and increasingly erratic behaviour eventually ended his career, and influence. His life would come to a drugged end, ruled a doctor-led homicide, in 2009, aged only 50. A rather unusual opening to the Second International Conference on Women and Sport, nevertheless.

Of course, the first person I rang was Simon with a, ‘You’ll never guess what just happened’ call, and the second was to my Mum. We called these my, ‘Ma, I got off the farm’ calls. Didn’t matter if I was in the next village, or in another country I would phone her, often from a call box. ‘Mum, you’ll never guess where I am’, pause, ‘Hello Jean, where are you today?’ half a beat for dramatic effect, ‘Mum, today I am…’ She patiently enjoyed my enjoyment. Mum was the best.

I recorded groups of young people and children making footballs out of discarded plastic bags and playing barefoot in my field research in Namibia. There wasn’t the same recycling of boots and shirts to Africa then that there is now, and making do didn’t involve any big brands. The plastic-bag footballs bounced really well, and had just the right weight for great crossing.

A proposed Neverland theme park was a ridiculous response to pressing post-conflict and post-colonial deprivation. Most of the two million souls living in Namibia would be born into poverty, especially after the recent civil war which had seen many young men killed, so most households were often headed by young women, barely out of school themselves. Access to education was by no means a given. Women’s groups with whom I conversed explained that finding food and water was such an important part of daily life, taking most of their time; so the idea of a game of football was an exhausting luxury.

The National Football Association of Namibia had been founded in 1990, shortly after independence from South Africa, and affiliated to FIFA in 1992. A women’s football section tried to promote the sport among female adults and girls, though it received little support from the national association. The Namibian National Sports Commission supported and tracked the development of female players in 1997. Volunteers like Julien Garises and others were leading the way, often funded by charities rather than the football bodies. I had connected with one such charity, Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO). Before returning to discuss the conference in Namibia, here is a little more on how I connected with Pauline Yemm, to understand what good fortune this was.

In 1997 Pauline had just returned to the UK after spending two years within the VSO scheme in Namibia. Established in 1958, the VSO had traditionally provided a gap year experience for public schoolboys (in the UK this means privately educated elite young men) before they went up to university. After broadening its remit to include sport for development and peace, the organization is now one option among many ventures that together constitute the panoply of charitable, voluntary and commercial programmes involved with gap years and internships.

I had met Pauline at an information gathering event organised by a funded researcher working with the FA, who was studying for a sociological PhD on the status of women’s football in England, the USA and Germany. The problem was, I was not funded by the FA, a distinction I later found to be important to the governing body, who wanted to control the narrative. While the funded FA researcher was able to advertise a number of roadshow-style events across the country to obtain data, I was not allowed inside as my research was unofficial.

I duly turned up anyway, since the events were advertised ahead of time in the public domain, and stood on the doorstep outside with my questionnaires. When players asked why I wasn’t allowed inside, and I responded that my research was considered unofficial, they were very enthusiastic about filling in the forms. Most followed up with phone calls, documents, memorabilia and photographs. The academic term for this is ´snowball sampling´, and my subsequent career has the generosity of women football players as its foundation, for which I remain so grateful 25 years on. I met a young woman only a few months ago at an elite coach event who remembered playing against my team in a bitterly fought match—and then me politely knocking on the dressing room door to ask the opposition to fill in my questionnaires.

The players who helped me also enjoyed confounding anything the FA ruled in relation to women’s football. So many women who had carried women’s football in very difficult times left the game when the FA took over in 1993, and rebranded the Women’s Football Association (WFA) with FA marketing. No one in women’s football that I had met so far liked the FA, except the very few females who worked at the governing body. I later learned it was a part of the broader anti-intellectualism of the organisation. A lot of people who are more compliant than bright work for the FA and women who had just started to be employed there wanted to fit in with that occupational culture. Thankfully now, increasing numbers are disrupting old patterns of working in the governing body, and I’ve been fortunate to work with more of these innovators recently.

Back in 1997, Pauline Yemm was one of the people who came along to the roadshows, and hearing I was already planning to go to the Namibia conference in May 1998, provided important background information on African women’s sport for development and peace. She also provided networked links for field study. In our conversations, it quickly became clear that the challenges for the female population in Namibia were immense, and my Western notions of sport, leisure and health needed considerable revision. So, I combined field research with attendance at the Windhoek conference, and was able to attend a number of impromptu meetings such as a gathering of women’s football administrators from Angola, Botswana, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Congo, Lesotho, Mozambique, Swaziland, South Africa and Mexico.

It was not just football. There were many stories of women in Africa engaging in sport because of the need for life skills for survival, such as being able to swim, or wade across, a river on the way to school, or college. The development for peace agenda was also a topic of academic study, but several of us had reservations, wondering why it was acceptable to parachute into a given social context, raise aspirations of assertive young women, only to leave after 12 weeks, or however long the project lasted. So there were a lot of discussions at the time about the ethical aspects of Western scholars doing academic work in Africa.

At this time, the academic literature on men’s football in Africa was not that extensive, although this would change in the next 10 years with a particular focus on migration. But the literature on women’s football was very thin, Eurocentric, and the problems that the administrators above discussed, such as national associations not funding flights to women’s international qualifying matches, were hardly known. No matter how little (or much) money a national association had, qualifying for men’s World Cups was a priority, because of the economic realities of there being no money in women’s football. Financial encouragement for women and girls was often presented as an economic luxury.

The Windhoek conference was associated with some stellar names in the world of women in sport, cemented in the popular imagination four years earlier by the inaugural Brighton conference entitled, ‘Women, Sport and the Challenge of Change’. The Brighton Declaration was one outcome of the 1994 meeting, attempting to obtain an undertaking from sports organisations, governments and non-governmental bodies to commit more resources to women’s and girls’ activities.

In what was essentially an attempt at cultural change, the International Women and Sport Strategy 1994–1998 aimed to co-ordinate many disparate efforts internationally. For this, a Working Group on Women and Sport was established to oversee change. The original target of 100 organisations was quickly overtaken and eventually doubled in those four years. Football was one sport of many to be involved. In early 1998 I was at another conference in Brighton where Hope Powell was announced as the new England women’s full time head coach, taking over from Ted Copeland.

So, by the time of the Namibia conference in May 1998, the International Women and Sport movement had grown to over 400 delegates from 74 countries. Windhoek responded to Brighton by a call to action, and a greater awareness of the need for connectivity with the UN, and other global actors who were advocating for greater gender equity.

However, coherent collective action proved difficult internationally. FIFA, the world governing body of football has had just nine Presidents since 1904, all male. Even the acting Presidents who filled in were male. Male-led governing bodies were not going to give up power voluntarily. There were too many first-class plane tickets, a surfeit of grand lunches, and the chance of being treated like royalty by global social elites. Who would trade that for something as nebulous as equality, diversity and inclusion?

Instead, Sepp Blatter, the incumbent FIFA President in 1998 was becoming popular amongst the African countries by establishing permanent national facilities. FIFA’s Financial Assistance Programme (FAP) was launched in 1998. In 2002, FIFA’s FAP contribution to Namibia was $198,000. This was in addition to the Namibia Goal programme, sponsored by FIFA, which provided $400,000 to fund the construction of a permanent administrative base. Through the FIFA Goal initiative, the national facility added a floodlit pitch with artificial turf in 2003. In 2004, FAP introduced a requirement for FIFA associations and confederations to invest at least 4% of their FAP funding into women’s football. This threshold was increased to 10% in 2005.

Without wanting to distract attention from the main focus here, those interested in the case study might like to follow up on my paper with Megan Chawansky, Namibia’s Brave Gladiators: gendering the sport and development nexus. There is also excellent work by the Berkeley-based Africanist Martha Saavedra Football Feminine: Development of the African Game: Senegal, Nigeria and South Africa in Soccer & Society 41: 3 (2003) 371–92.

In comparison, in the UK the real difference for women’s sport generally was National Lottery funding, introduced in 1995, which signalled greater governmental commitment to elite achievement and grassroots participation. Helpfully, Olympic sports are not divided into women’s medals, and men’s medals, just a national medal table. In the midst of Cool Britannia, the UK was using sport as a tool of soft diplomacy.

Investing in women’s sport had historically been seen in the UK as bad form, but after World War Two, Cold War rivalry had meant that countries like East Germany, the USSR, Hungary and Finland had been able to win medals at an economical rate by funding female athletes in relatively neglected disciplines across gymnastics, track and field athletics, swimming and Winter sport. The British were famously slow to follow, most notably winning just one gold, eight silver, and six bronze medals for the 300 athletes sent to the Summer Atlanta Games in 1996. This left Team GB, 36th nationally overall, and was also highly gendered as Britain sent 184 men and just 116 women. All of the 1996 medals were won by men, apart from Denise Lewis’ bronze in the heptathlon. This was not for lack of world class talent. Kelly Holmes finished fourth in the 800 metres, Paula Radcliffe finished fifth in the 5000 metres, and Liz McColgan finished a distant 16th in the marathon.

By now the Sports Council had become devolved and in September 1996 the English Sports Council (ESC) had £593 million to distribute. By 1997 it would become rebranded as Sport England. Those interested further can access the archives at the Cadbury Research Library, at the University of Birmingham.

The unification of the Olympic sports under the banner Team GB, saw a rapid change in culture so that at the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games, in spite of only 129 women compared with 181 men in the British contingent, 11 gold medals were returned, of which Denise Lewis (heptathlon), Shirley Robinson (sailing), and Stephanie Cook (modern pentathlon) were included. A total of 10 silver medals saw rowers Guin Batten, Miriam Batten, Katherine Grainger and Gillian Lindsay rewarded as a team, alongside Judoka Kate Howey as an individual, and equestrians Jeanette Brakewell and Pippa Funnell as part of a mixed team.

Kate Allenby won a bronze in the modern pentathlon, as did Kelly Holmes and Katherine Merry in the track and field athletics, and Yvonne McGregor in the cycling. Therefore, four of the Team GB seven bronze medals were won by women in Sydney. The total of 28 medals in all raised Team GB to 10th in the international table. Britain had belatedly learned that funding elite female athletes was good for national morale. But women’s football had only just become an Olympic sport in 1996, and the problem of the Team GB representation, rather than the home nations, meant that this sport would not become significant for elite female players until 2012.

The lottery funding was not just good news for Olympic and Paralympic sports. When organisations such as the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), which had been for many years a de facto world governing body of the sport since 1787, were turned down for lottery funding because they refused to admit women, they changed their rules to admit 10 honorary female members. That concession to so few females invited to join masked the 18,000 male members, but nevertheless released lottery funding opportunities to an already wealthy and culturally conservative institution.

In the midst of all this change in relation to the status of women’s sport internationally, I was in Namibia trying to find my academic voice for the first time. For those of you who are reading this at the beginning of your Doctoral journey, maybe a bit concerned about your knowledge-base, and suffering from the dreaded Imposter Syndrome, my advice would be to get over yourself. Honestly? Such naval-gazing is a displacement activity. Get on with it. You will find your tribe. My first presentation went OK, but was comparable to early Doctoral work. Promising, but not the finished package. People were supportive. Onwards.

I knew that the international collective action of the Second World Conference on Women’s Sport was inspirational, but it was also reliant for funding and recognition on organisations which had obtained their historic authority through the exclusion of women. Often explicitly so. Fabled ‘progress’ was a myth of women playing catch-up to a future as yet unarticulated.

Like many conferences I would attend on women’s sport over the next 25 years, it was also preaching to the already converted. Olympic conferences, FIFA conferences, UEFA conferences, general women in sport conferences—the same tone of progress over and over. While there was strength in finding others doing this work, it also made me aware of who was not present. That is, not everyone could afford to get on a plane to discuss such issues. The vast majority of community champions were volunteers, and they were thin on the ground as conference delegates. So, I would become increasingly uneasy of those like myself in relatively privileged positions of power, who could be funded to such events, compared with those who made a practical difference.

Quite aware that this consciousness was a luxury in itself, it motivated me to give a platform to the voiceless whenever I could. After all, at this time I was playing football for my local team and running it as a volunteer, serving as a volunteer on the East Midlands women’s football committee, working through my FA coaching badges and doing research into women’s football.

An average football player for my local side, I was intelligent enough to know I was ordinary at best. So, as an attacking midfielder, I obtained the ball, and passed to the good players. It was a simple plan. I could read a game and anticipate where people would put the ball and how they would react. In spite of my limited talent, I fancied myself playing in the style of David Ginola, the French midfielder who had signed for Newcastle United in 1995 and so became Jeanola. Well, everyone in women’s football had a nickname, as Alyson Rudd remarked somewhat sarcastically in Astroturf Blonde (1999), so it sort of stuck.

I watched my Premiership doppelganger from the ‘Cow Shed’, better known as the East Stand at Filbert Street, home of Leicester City FC. What the corrugated-iron roofed Cow Shed lacked in comfort, warmth and any concession to the spectator experience, was more than made up for by having front row seats just below pitch height. As we sat, (in the late 90s often waiting to see what haircut Beckham would reveal from under his hat/cap/beanie), our eyeline was at the same level as the pitch. This gave a real sense of the player’s speed as they sped down the wing. It was pure adrenaline for a £25 ticket.

Like Becks, Ravanelli, and Vialli, Ginola was one of the players who revelled in being so close to fans and putting on a show. If I lacked any of his skills, at least I did have good hair and plenty of attitude, if not altitude. Transferring from ES Barwell to Loughborough Dynamo in the 1999/2000 season, the programme described me as an experienced tough tackling midfielder, which is football shorthand for saying my knees (and the rest of me) were 36, and I’d not a lot of elegance on the ball. By 2003/4 Dynamo asked me to be player-manager, a polite way of asking me to bow out as a player, and soon! So being embedded in the women’s football community, I got to meet unpaid volunteers daily, whereas a conference was a one-off event, and a plush one at that.

To round off the day of my presentation in Windhoek we had a conference dinner. A local man joined us, and began, over dessert, to tell me that he would like me for a wife as I had a pretty face. His mother, he continued, would like me because I had hardworking hands. Declining his charming invitation of marriage, I managed to slip away from proceedings early back to my room. I anticipated the rest of the conference would be relaxing and a chance to decompress.

I was wrong.

On the second day I was approached in a coffee break by two very glamorous blonde women in understated business suits. One I could tell was an athlete, complete with firm handshake and an unwavering gaze. She had the posture of someone used to commanding a room. She introduced herself as Donna de Varona, Chair of the Organising Committee of the 1999 Los Angeles Women’s World Cup. Wow. Also known by her married name Donna de Varona Pinto, she was not just an athlete. She had retired from Olympic swimming after representing the US in 1960, and winning two gold medals in 1964. One gold was in the inaugural women’s 400-meter individual medley, and the second was a member of the 4×100-meter freestyle relay, both world record performances. An activist and pioneer of women in sports broadcasting, in the mid-1970s, de Varona joined Billie Jean King in establishing the Women’s Sports Foundation (WSF), serving as the first President from 1979 to 1984. Helping to raise millions of dollars for the WSF, de Varona was also regularly consulted by governments, the Olympic movement, anti-doping agencies and those applying Title IX in the US, as well as for her broadcasting work, advice on gender equity issues and grass roots provision.