Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

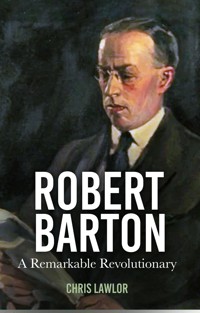

Robert Childers Barton was one of the most enigmatic figures to emerge from the Irish Revolution, and his place in history was assured when he signed the Anglo-Irish treaty. Although he was a confidante of de Valera, Barton accepted the terms on offer in 1921. He voted for the document in both the Cabinet and the Dáil, recommending the treaty to the House in his Treaty Debate speech. Subsequently, however, he took the anti-treaty side in the Civil War. Although he was central to the birth of the nation, Barton has remained understudied and neglected. This first study of his life focuses on his role during the Irish Revolution, charting his political journey from a Unionist background, through Home Rule and Dual Monarchism, to Republicanism and his later anti-treaty stance. Using multiple sources, including extensive archival material, this book traces the life, times and legacy of a remarkable revolutionary.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 382

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

In memory of Professor Raymond Gillespie, late of Maynooth University, who did so much to help me on my academic path over the years. Ar dheis Dé go raibh a anam dílis.

Cover picture: Portrait of Robert Barton by Sir John Lavery, oil on canvas, 1921.(Collection and image © Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin)

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Chris Lawlor, 2024

The right of Chris Lawlor to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 816 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

List of Illustrations

About the Author

Acknowledgements

List of Abbreviations

Introduction

Rationale and Background

Sources

1 Early Influences (1881–c.1893)

2 A Traditional Education and a Political Conversion (1894–1916)

3 An Easter Rising (April 1916 and its Immediate Aftermath)

4 The Appeal of Sinn Féin (Summer 1916–Summer 1918)

5 Selected and Elected (June 1918–January 1919)

6 Prisoner, Director for Agriculture – and Fugitive (February 1919–January 1920)

7 Another Prison Term – and a Truce (January 1920–July 1921)

8 Plenipotentiary Status and High Hopes (Summer – Autumn 1921)

9 Background to the Delegations (October 1921)

10 Conferences and Sub-conferences (Early October – Early November 1921)

11 Twists, Turns – and Tensions (3 November–3 December 1921)

12 From Plenipotentiary to Signatory (4–6 December 1921)

13 Debating the Issue (December 1921–January 1922)

14 Uncivil Recriminations and Civil War (January 1922–December 1923)

15 A Return to a Life of Public Service (January 1924–August 1975)

Conclusion

Appendices

1 Recommendation from Captain Booth for Robert Childers Barton, 17 December 1915

2 Lloyd George–De Valera Correspondence, 7 and 12 September 1921

3 Robert Barton’s Treaty Debate Speech, 19 December 1921

4 West Wicklow Comhairle Ceanntair of Sinn Féin to Robert Barton, 8 June 1924

Bibliography

Endnotes

List of Illustrations

1 Glendalough House, Annamoe, as Robert Barton would have known it.

2 Barton’s 1908 diploma in economics (with distinction) from Oxford University.

3 Devastation greeted Second Lieutenant Barton on his return to Dublin in 1916.

4 Small, broadside (c.10in × c.6in) 1918 election advertisement for Robert Barton.

5 Sinn Féin election poster 1918, addressed to ‘The Women of Wicklow’.

6 Dunlavin Courthouse, where councillors demanded Barton’s release on 13 July 1920.

7 General Macready entering the Mansion House, 8 July 1921.

8 Irish delegates leaving for the London peace conference, 12 July 1921. (L–R: Arthur Griffith, Robert Barton, Éamon de Valera, Count Plunkett and Laurence O’Neill).

9 Barton (between Gavan Duffy and Griffith) returns to Dublin, 8 December 1921.

10 Barton’s pamphlet The Truth about the Treaty and Document No. 2 (February 1922).

11 Robert Barton’s name on a pact election poster, June 1922.

12 Dulcibella Barton pictured with Countess Markievicz’s cocker spaniel, Poppet.

About the Author

Dr Chris Lawlor is a former head of the history department of Méanscoil Iognáid Rís in Naas, County Kildare. He won the County Kildare Archaeological Society’s Lord Walter Fitzgerald Prize for Original Historical Research in 2003 and the Irish Chief’s Prize for History in 2013. He was also the winner of the Dunlavin Festival of Arts Short Story Competition in 2001 and the Ireland’s Own Short Story Competition in 2022. He has contributed numerous articles and chapters to many journals and compilations, and his twelve previously published books include The Little Book of Wicklow and The Little Book of Kildare. He continues to write in his retirement.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank my family, academic mentors and historians, the ever-helpful staff of the various libraries, archives and repositories who helped me to bring this work to fruition, and Ele Palmer, Nicola Guy and the team at The History Press.

Thank you to my wife, Margaret Lawlor; Declan Lawlor; Jason Lawlor and his wife Mary; Michael Lawlor and his wife Orla. Thank you for all your support, encouragement and help. Thank you also to my grandchildren, Caitlin, Cian and Bronagh, for often lifting my spirits.

Thanks also to each of the following: Prof. James Kelly, St Patrick’s College, D.C.U.; Prof. Mary Ann Lyons, Maynooth University; Dr Daithí Ó Corráin, St Patrick’s College, D.C.U.; Dr Ida Milne, St Patrick’s College, Carlow; Hugh Beckett, Irish Military Archives; Lisa Dolan, Irish Military Archives; Vincent Buttner, National Archives of Ireland; Vera Moynes, National Archives of Ireland; Selina Collard, University College Dublin Archives; Aisling Lockhart, Manuscripts and Archives, Trinity College, Dublin; Anne Marie Saliba, Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin; Frances Clarke, National Library of Ireland; Glenn Dunne, National Library of Ireland; Damian Murphy, National Inventory of Architectural Heritage; Colum O’Riordan, Irish Architectural Archive; Brian Crowley, Kilmainham Gaol Museum; Ciarán McGann, The Houses of the Oireachtas Service; Peter Brooks, Royal Agricultural University, Cirencester; Dr Mari Takayanagi, Parliamentary Archives, London; Sophie Bridges, Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge; Adam Green, Trinity College Library, Cambridge; Kaili Smith, Imperial War Museum, London; Catherine Wright, Wicklow County Archives; Gerlanda Maniglia, Wicklow Local Studies Department; James Durney, Kildare County Archives and Local Studies; Maura Greene, Dunlavin Library; Joan Kavanagh, Rathdrum Historical Society; Peadar Cullen, West Wicklow Historical Society; John Dorney, The Irish Story website; Tommy Graham, History Ireland; Florence Grace and Maura O’Neill, Dunlavin Writers’ Group; Tom Noone, Mary McCabe, Andrew Keating, Kathryna Phibbs and Joseph Kelly, Meánscoil Iognáid Rís; Rita Evans and Joe Walsh, former colleagues.

Special thanks to Dr James Lee, Dunlavin, who restored me to good health at an important time in my research.

List of Abbreviations

A.C.C.

Agricultural Credit Corporation

B.A.

Bachelor of Arts

B.M.H.

Bureau of Military History

D.C.U.

Dublin City University

DE

Dáil Eireann

D.I.

District Inspector, R.I.C.

D.I.B.

Dictionary of Irish Biography

Dip. Econ.

Diploma in Economics

D.M.P.

Dublin Metropolitan Police

E.S.B.

Electricity Supply Board

G.A.A.

Gaelic Athletic Association

G.H.Q.

General Headquarters

G.O.C.

General Officer Commanding

G.P.O.

General Post Office

H.M.

His/Her Majesty’s

I.C.A.

Irish Citizen Army

I.M.A.

Irish Military Archives

I.P.P.

Irish Parliamentary Party

I.R.A.

Irish Republican Army

I.R.B.

Irish Republican Brotherhood

I.T.G.W.U.

Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union

I.V.F.

Irish Volunteer Force

J.P.

Justice of the Peace

M.A.

Master of Arts

M.R.A.C.

Member of the Royal Agricultural College

MS

Manuscript

M.S.P.C.

Military Service Pensions Collection

N.A.I.

National Archives of Ireland

N.L.I.

National Library of Ireland

O.T.C.

Officers’ Training Corps

Ph.D

Doctor of Philosophy

R.I.C.

Royal Irish Constabulary

R.T.E.

Radio Teilifís Éireann

T.C.D.

Trinity College Dublin

T.D.

Teachta Dála (member of Dáil Eireann)

U.C.C.

University College Cork

U.C.D.

University College Dublin

U.C.D.A.

University College Dublin Archive

U.V.F.

Ulster Volunteer Force

W.C.C.

Wicklow County Council

WS

Witness Statement (to Bureau of Military History)

WW.C.A.

Wicklow County Archive

Introduction

RATIONALE AND BACKGROUND

In December 2021, I participated in a History Ireland ‘Hedge School’ entitled ‘Robert Barton: forgotten man of the Irish Revolution?’ with other contributors John Dorney (The Irish Story website), Joan Kavanagh (Rathdrum Historical Society) and Catherine Wright (Wicklow County Archives), chaired by Tommy Graham (History Ireland).1 I have always thought that Barton was an under-studied figure in Irish history, particularly given his central role during the Irish revolutionary years and the socio-economic effects of his later public service at the head of the Agricultural Credit Corporation and, especially, Bord na Móna. The title of the 2021 Hedge School reinforced my view. As a plenipotentiary in the Irish delegation sent to London to secure a political agreement in the wake of the War of Independence, and as a signatory of the Anglo-Irish treaty, Barton’s role was integral in the birth of the Irish state … yet, amazingly, he still awaits a biographer. It is incredible that this is so, and the more I thought about it, the more convinced I became that some kind of brief study of Barton’s life, times and contribution to Irish history should be written. In particular, I thought it would be fitting, as we leave the decade of centenaries behind us, that some account of the part played by Barton, and his contribution to the events of that decade a hundred years ago, should be placed on record. That thought was the genesis of this study.

Of all the people involved in the Irish Revolution of c.1913–23, it fell to Robert Barton to choose acceptance or rejection of its negotiated settlement, the Anglo-Irish Treaty, and it is no exaggeration to say that in December 1921 he singly carried the full weight of a nation’s expectations on his shoulders during the final hours before the agreement was fully signed. Given his prominence at this crucial time, this study seeks to establish just who he was, to examine his part in the Irish Revolution with particular reference to his central role as a key player during the treaty negotiations, to give a brief overview of his later life and, finally, to evaluate his legacy as a political figure. Please note that all quotations in the text, appendices and endnotes retain the original spelling and punctuation (including upper case letters).

This work does not purport to be a definitive biography of Robert Childers Barton. He lived a very long – and very full – life, eventually passing away at the age of 94. It would take many years of extensive, in-depth research to cover Barton’s eventful existence during those ninety-four years. As the title suggests, this study concentrates on Barton’s contribution to Irish history during the revolutionary period, and in particular during the period 1916-23 – from the Easter Rising to the Civil War. It also briefly covers his early life before 1916 in an effort to give an overview of the influences that brought him into the Irish national movement, and very briefly addresses his later life after 1923 in an effort to outline his enormous public service within the new Irish state as it morphed from the Free State to the Republic, and the effect of his work on the new Ireland. However, both his early and later life are only sketched briefly – I did contact Bord na Móna, only to be told that the company (incredibly) does not have an archivist and there is no access to sources. In any event, the principal focus of this study concentrates on the crucial revolutionary period, centred in Barton’s case on the years 1921–22, and including the treaty negotiations, the signing of the document, the treaty debates and the eventual outbreak of civil war.

SOURCES

One of the problems of working on this period is the sheer volume of sources available. This is not to say that gaps do not exist; they certainly do – but this was an age of increasing literacy, and this is reflected particularly in the publication of periodicals. National and local newspapers, pamphlets, magazines and other contemporary publications abound. One must beware of bias in the reporting, of course; newspapers could be unionist or nationalist, pro- or anti-treaty in sympathy – just like those who wrote them or those who read them. The most immediate problem working with press sources was often choosing what to include and what to omit. Other printed sources, including election flyers and political pamphlets, also contributed to the overall picture. The most significant manuscript sources for the revolutionary period from 1916 to 1923 were undoubtedly those held in the Irish Military Archives (I.M.A.), Dublin. These include Robert Barton’s witness statement, and some information relating to Barton is also found in other witness statements such as those of his sister, Dulcibella, and Mrs Austin Stack. The I.M.A. also contains many other records from the period including, for example, I.R.A. pension application files. The National Archives of Ireland and the National Library also hold some relevant material, and sources from other Irish archives outside of Dublin such as Kildare County Archives and Local Studies Department and Wicklow County Archives, and some British repositories, also helped to put flesh on the bones of Barton’s eventful life and valuable contribution to the Irish state. Secondary sources specifically relating to Barton (or his family) are thin on the ground. Apart from my own short piece from 2014,2 they are confined to articles or chapters such as those by Michael Fewer,3 Catherine Wright,4 Turtle Bunbury,5 and Pauric Dempsey and Shaun Boylan.6 Unsurprisingly, though, Barton appears en passant in many general publications dealing with the revolutionary period, most notably Pakenham’s Peace by ordeal,7 and Macardle’s The Irish Republic.8 Occasionally (when it was necessary to denote the passage of time in Barton’s constituencies), events in the village of Dunlavin have been referenced. The village was chosen because it was centrally located in both of Barton’s constituencies (located, as it is, on the north–south border of the baronies of Upper and Lower Talbotstown in the West Wicklow constituency and on the east–west county boundary in the constituency of Kildare-Wicklow), and because a study of the area during the Irish revolutionary period has been published previously.9 I have tried to weave the various snippets found in relation to Barton in both primary and secondary sources into some form of coherence in this work.

Almost half a century ago, Professor Patrick Corish (whose lectures in Maynooth I was privileged to attend), delivered a stark warning to historians writing about mid-seventeenth-century Ireland by telling them that they ‘risk disturbing ghosts’.10 This is even more the case, I think, when one is writing about events that happened a century ago, or less. Moreover, many of the events of this formative time in our history were deeply divisive, and have moulded political attitudes, in some cases right up to the present day, so Barton’s role may be perceived in different ways by various groups. One thing is certain: more and more primary sources relating to this period will be opened up for research, and will be made available online, as the years progress. The new information will complement what has already been discovered – but it may also contradict some sections of it. It will be for future generations of historians to make sense of any new findings and to re-interpret Barton’s words and actions in a new light. It is my sincere wish that some Ph.D. student or historian from the world of academia will take up the challenge of researching and writing a more comprehensive biography, and to any future student of Barton’s life, times, legacy and contribution to Irish history, I humbly offer this study, with its many imperfections, as a starting point.

Chris Lawlor

Dunlavin

March 2024

1

Early Influences

(1881–c.1893)

Robert Barton’s background was not that of a typical Irish revolutionary. At least, it is not the background that one would expect for such a figure, as it is somewhat arguable whether there is a ‘typical’ background for an Irish revolutionary. For example, republican Theobald Wolfe Tone (known as ‘the Father of Irish Republicanism’) came from a wealthy Kildare Protestant family;1 Home Rule leader Charles Stewart Parnell came from a Protestant landlord family;2 Countess Constance Markievicz came from an elite, privileged family;3 and other Irish nationalist and republican leaders during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries emerged from unexpected and surprising backgrounds. Robert Barton was born on 14 March 1881 into an elite, unionist, Protestant, landlord family in County Wicklow, whose wealth was increased by their interest in the French vineyards of Barton and Guestier. Bob Barton’s parents were Charles William Barton of Glendalough House, Annamoe, and his wife, Agnes, daughter of Rev. Canon Charles Childers, H.M. Chaplain at Nice and canon of Gibraltar.4 The Barton family of Glendalough House were also pillars of the local Church of Ireland community, and on 14 September 1894 the 13-year-old Bob joined the Derrylossary branch of the Church of Ireland Temperance Society.5 As an adult, Barton readily proffered the information that his father, Charles William, ‘was a loyal supporter of the British administration here [in Ireland]’.6 Moreover, Charles Barton’s political views caused him to fall out with his more famous neighbour, Charles Stewart Parnell, who became the president of the Land League and the charismatic leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party in their campaign to gain Home Rule for Ireland. According to R. F. Foster, Robert Barton’s father and Parnell were ‘close friends as young men, but politics sundered their friendship completely. Barton was a strict Unionist.’7 Despite this falling out, Parnell was invited to Glendalough House to view a big tree that had been blown down in a storm in 1888, and Barton remembered his nanny pointing out the great ‘uncrowned king of Ireland’ to him as he gazed out through his playroom window.8

The young Robert Barton grew up at Glendalough House, in the company of his older, orphaned cousin, Erskine Childers, who had moved to Annamoe to live with his Barton cousins in 1876. The Glendalough House cousins would enjoy a lifelong bond of friendship. This imposing residence was located in a beautiful setting of parkland, woodland, river and mountains. It replaced an earlier house owned by the Hugo family. The grounds included a formal garden with yew trees set between the stables and the house, with an enclosed garden beyond. The long, Gothic stables, dating from 1838 (shortly after Barton’s grandfather, T. J., bought the estate from Captain Hugo),9 originally comprised a separate building, but an extension dating from c.1880 later joined the stable block to the main house. The house itself also dates from 1838, and is a highly ornate mansion built in the Tudor Gothic style. This is somewhat unusual, as the building of larger, ornate, landlord houses tended to peter out in the mid-to late-nineteenth-century, as by then, the Anglo-Irish had lost much of the confidence needed to build on a grand scale.10 Generally, big houses built during this later period were simpler, and often smaller, than their eighteenth-century predecessors, which dated from the heyday of the emergence of the Irish landed elite.11 Glendalough House, with its fanlight doorway, eaved roof, hall enclosed on three sides by a gracefully joined staircase, imposing rooms, ornate chimney pieces (including one piece of possible Russian origin), large windows and castellated features was a statement building.12 It emanated an unmistakable aura of wealth, power and social control, and compared favourably with other big houses in County Wicklow and beyond. At a glance, it was evident to all, including, in his childhood, the young Robert Barton, that the owners of such a house, which dominated the cultural landscape of the locality, were part of the landed elite, and that they belonged to the establishment that controlled nineteenth-century Ireland.

An account of a visit to Robert Barton at Glendalough House in the 1940s paints a portrait of a wealthy, comfortable lifestyle in impressive surroundings:

Fig 1. Glendalough House, Annamoe, as Robert Barton would have known it. (Image (2/41X1) courtesy of the Irish Architectural Archive)

A long drive with magnificent Wellingtonias and other trees dotted about the park led to a large L-shaped house, with a covered porch and wide steps leading to the entrance hall … The house smelt as all old houses do, of old oak. He took us first to the Library for drinks. The walls were lined with books which were almost entirely concerned with Irish history. There was also a complete set of Maria Edgworth’s novels … A staid, pale, disapproving butler announced the fact that luncheon was served. We moved into the dining-room which was hung with Erskine and Barton portraits, going right back to the days of Queen Elizabeth, when the Bartons first settled in Ireland. We had a magnificent meal of sirloin of beef with an enormous dish of fresh garden peas, beans and new potatoes, followed by pineapple, fresh raspberries and extraordinarily good sherry. After lunch he took us first to see his immense walled garden and greenhouses, and a vast tree that almost overshadowed the house. [There was] a new rockery with dwarf junipers and cypress trees that he had planted by the sides of a little lake on the hillside, with waterfalls that fell steeply down to a lower lake. We then walked along through a forest of primaeval oak … This track wound its way past gnarled, bent and withered trees, through vast undergrowth and came out at a stout stone lodge gate that had been the dairy, and then converted into a village school. In the distance I heard the call of curlews on the sides of the mountain called Scard, which is Barton’s grouse moor. We crossed a road, climbed a stony, rough, walled lane, and soon found ourselves looking down on a lake, shut in on three sides by the mountains. This was Lough Dan and on its black, cold-looking surface, I saw a rowing-boat painted scarlet. On the way back to the house, he took us up some outside stone steps to a room in which the wife of one of his servants was spinning wool, while her son sat in front of the radio with his ear close to it, listening to a running commentary on the football match between Meath and Kerry … After a tea, which included some of the finest honey in comb that I have ever eaten, Barton drove us home.13

Glendalough House also incorporated part of an older house. Prior to the Bartons, the previous owners were the Hugo family. Captain Thomas Hugo was particularly well known to, but not particularly well remembered by, the ordinary people of the Annamoe region. Hugo, a former High Sherriff of County Wicklow and an ultra-loyalist, had been particularly active during the 1798 rebellion period in County Wicklow.14 Speaking in a television interview in 1969, Robert Barton, by then an elder statesman, wryly referred to the fact that he had lived in the same place as the notorious Thomas Hugo.15 As a child, he had lived ‘in the heart of the rebel area of County Wicklow’ and had ‘absorbed quite a lot of national sympathies’.16 He had also absorbed much of the history and folklore of Glendalough House and its hinterland surrounding Annamoe during his long life. He left behind a collection of this material, with some personal reminiscences, which is now housed in the National Archives of Ireland.17 According to Barton:

Mr. Hugo of the 1798 rebellion time, was a captain of the yeomanry, who had slaughtered … many rebels around [Glendalough] House. The house had got such a bad name that it became known as ‘the slaughterhouse’. The people that my father and I were employing were descendants of those who were shot in 1798. My sympathies were with them, that’s how I originally came into the national movement.18

It is interesting that, even in old age, Barton did not refer to the people on his estate as ‘tenants’. This may have been due to a genuine paternalistic pride that Barton felt as an employer. However, it may also have been an attempt to distance himself (and his landlord family) from the language of landlordism, as land reform had been a divisive topic during the first half-century or so of the existence of an independent Ireland, first as a free state and later as a republic. In a conversation with an old university friend in 1948, Barton told him that Irish people particularly wanted to displace English landlords who left their properties in the hands of their agents, stating, ‘That’s almost our oldest grievance, being under the heel of the agent.’19 Landlordism and its messy, protracted aftermath had left long shadows, and even in 1969, discussions about and arguments over land could become heated. Under the first Minister for Agriculture appointed after the establishment of the Free State, Patrick Hogan, the partial break-up of landlord estates (and, in some cases, demesnes) and some redistribution of agricultural lands was undertaken by the Land Commission. However, Land Commission farm size remained small. Inevitably, in County Wicklow as elsewhere, there were winners and losers in this process. Expectation did not always match reality and, overall, agricultural labourers and smallholders fared badly.20 The early years of the fledgling Free State witnessed a flight from the land as many smallholders (or, after their deaths, their sons and daughters) sold up and shipped out. Their land was often bought by neighbouring strong farmers. As recently as the late 1990s, during the height of the Celtic Tiger boom years, the author spoke to two County Wicklow residents who had bitter memories of these events, which they both referred to as ‘the time of the land grabbing’.21 Whatever Barton’s motives for referring to his tenants as ‘employees’ (and perhaps he had more than one), these were the people among whom he grew up, and his sympathy for – and empathy with – them strongly suggest that his journey towards Irish nationalism began in his boyhood years, which he spent in the Annamoe area, at least during holiday periods.

2

A Traditional Education and a Political Conversion

(1894–1916)

As a boy, Robert Barton conformed to the educational model of many of the sons of the Irish landed elite, whether gentry or aristocracy, and received his education in England. He received a public school education at the famous Rugby School in Warwickshire, before progressing to the Royal Agricultural College in Cirencester, Gloucestershire, and on to Oxford University. Barton received his diploma from Cirencester in 1901.1 He then studied at Christ Church College, Oxford, and was awarded a B.A. and subsequently, on 13 June 1908, a Dip. Econ. (Diploma in Economics) from that august institution.2 Barton’s educational progression fell within the expectations of his family and other members of the landed elite. In many ways, it was the traditional education received by the sons of Irish landlord families; it precisely mirrored, for example, that of Pierce O’Mahony, another young man from County Wicklow’s landed elite, from the village of Grangecon, a quarter of a century or so earlier.3 O’Mahony had established an Irish Home Rule Club at Magdalen College, Oxford,4 and during his time in Oxford (and probably Cirencester), Barton was also politically active. He lived on the same college staircase as Stuart Petre Brodie (S. P. B.) Mais, who went on to become a prolific author of travel books, journalist and broadcaster.5 In one of his books, Mais reminisced about how Barton had a profound effect on his own political opinions regarding Ireland. According to Mais, Barton:

first set me thinking of the English treatment of the Irish and aroused in me a sense of disgust at our barbaric tyranny and of sympathy with the movement to free Ireland from English rule. I have no Irish blood in my veins, but I felt an overpowering desire to serve the Irish cause in any capacity that Barton suggested.6

Some years later, in 1914, Mais thought of Barton again. By that time, he was on the staff at Sherborne, a public school in Dorset, and was an officer in the O.T.C. Mais reveals that:

Two of my colleagues and fellow-officers, both Englishmen, were so angry at Carson’s threat of violence in Northern Ireland that they decided to throw in their lot with Sinn Féin and join the Southern Irish. I remembered Barton at Christ Church and felt that I too ought to do something about it. We were on the point of doing something about it when our attention was diverted by Germany and we found ourselves embroiled in a war of quite another sort.7

Fig 2. Barton’s 1908 Diploma in Economics (with distinction) from Oxford University. (Image (Barton Papers, WWCA/PP1/19) courtesy of the Wicklow County Archive)

There is no doubt that Frank Pakenham was correct in his assessment when he stated that Barton had ‘already passed from Unionism to Nationalism by the time he left Oxford’.8 However, he was not the only nationalist in the otherwise staunchly Unionist Barton family. His sister Dulcibella (known as ‘Da’) was also drawn to the nationalist cause. Dulcibella was two years older than Robert, and she probably influenced his political opinions. Her later testimony revealed that both siblings ‘took in the Sinn Féin newspaper in the early days’, which must have irked their parents, who ‘were very conservative and would be absolutely opposed to the opinions expressed in that paper’.9 The newspaper in question was first printed in 1906,10 and there is no doubt that Barton was attracted by Sinn Féin policies, as he made a donation of £50 to the organisation in 1907.11 Barton may also have been interested in the economic self-sufficiency propounded by Sinn Féin, the new, fledgling political movement led by Arthur Griffith,12 as he worked for the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society (sitting on its committee from 1910),13 and was deeply involved in the co-operative movement championed by Sir Horace Plunkett.

Plunkett’s co-operative movement was supported by all shades of political and religious opinion, both north and south. He is principally remembered for his work with the co-operatives, but he had greater objectives regarding social justice. Plunkett wanted to restore a mutually beneficial relationship between urban and rural Ireland, which had been devastated by long-term poverty and emigration. His scheme for the regeneration of rural areas was based on co-operation and education, and he wanted to modernise agriculture, base rural commerce on the co-operatives and improve the rural economy.14 Plunkett’s agricultural aims for rural Ireland mirrored many of the ideas and ideals forming in Barton’s young mind. They were also compatible with the policies of self-sufficiency being put forward by Sinn Féin, a party later associated with Irish republicanism, but Barton was far from supporting any form of republicanism at this early point in his life. In 1908, he undertook a tour of co-operatives in the west of Ireland, in the company of his cousin Erskine Childers (and possibly also accompanied by Horace Plunkett),15 and having seen the horrendous level of rural poverty in the region,16 he returned fully convinced of the absolute necessity of implementing Home Rule for Ireland.17

Thus, Barton’s early support for Sinn Féin was not as radical as it might appear at first glance. The original Sinn Féin Party, founded by Arthur Griffith in 1905,18 advocated dual monarchism based on the post-Ausgleich (1867) Austro-Hungarian model, where the monarch would rule both Ireland and Britain, but the two islands would have totally separate parliaments with full powers within their respective jurisdictions. Dual monarchism was perhaps a refinement on the idea of ‘mere’ Home Rule, rather than a step beyond it, since both policies envisaged two parliaments under a single monarch (albeit, in the case of dual monarchism, more or less co-equal parliaments). Thus, by 1910 or so, Robert Barton’s political ideology had advanced as far as that of his old neighbour, the Home Ruler Charles Stewart Parnell, or perhaps gone a little way (but only a little way) beyond it, as Barton seemed to toy with the idea of a dual monarchy for a while. Nevertheless, either way, it is safe to assume that Barton’s political goal was to see the establishment (or re-establishment) of an Irish parliament in Dublin at this stage. The question must now be asked – why did Barton move beyond Home Rule and become more radicalised?

Events during the period 1912–14 conspired to move Barton beyond his comfort zone as a constitutional supporter of Home Rule. These were the years of the ‘Home Rule Crisis’, which was precipitated when the parliament in Westminster passed a Home Rule Bill in 1912. This had happened twice before (in 1886 and 1893), and these bills had been rejected by the House of Commons and the House of Lords respectively. However, the 1912 bill was different, due to the terms of the Parliament Act, which had been passed the previous year. Basically, the Conservative-dominated House of Lords could now only delay the third Home Rule Bill for two years, after which it would automatically become law. Alarmed Ulster unionists organised themselves to oppose Home Rule, forming the paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force (U.V.F.) to resist the passage of the new bill. Inspired by Eoin McNeill’s article ‘The North Began’,19 Irish nationalists countered this threat to the implementation of Home Rule by establishing the Irish Volunteer Force (I.V.F.), to fight for the introduction of Home Rule. This was the situation that prompted S. P. B. Mais’ decision ‘to throw in his lot with Sinn Féin and join the Southern Irish’. Barton, meanwhile, supported the aspirations of the I.V.F., but the movement split into two sections when the First World War began in 1914.

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (I.R.B.), a small, shadowy, subversive separatist group who espoused republicanism, rejected gradualism and favoured radicalism and armed revolution,20 had managed to infiltrate the I.V.F. Hence, when the vast majority of the Volunteers answered the Irish Parliamentary Party (I.P.P.) leader John Redmond’s call to join the British army when the First World War began, clandestine I.R.B. activity ensured that a rump of militants stayed behind and eventually staged the Easter Rising in 1916. The smaller group of separatist militants who did not support Britain’s war effort retained the name ‘Irish Volunteers’, while those who joined the British army to fight for Home Rule (which they believed must be implemented after the war in return for their military service) were known as the National Volunteers.

Robert Barton, perhaps inspired by his family’s military background, or possibly because of a sense of duty and a desire to oppose German militarism, supported the National Volunteers. Perhaps both motives were at play – the one does not preclude the other, and he may have had other motives as well. In his witness statement to the Bureau of Military History (given in 1954), Barton revealed: ‘I was a member of the National Volunteers. I worked in the office only and did not drill or parade. I managed the office for [Inspector General] Colonel [Maurice] Moore. I knew Count Plunkett, Bulmer Hobson, The O’Rahilly, Eoin MacNeill and quite a number of other Volunteer leaders.’ Barton continued his account thus: ‘I was in the office when the split in the Volunteers took place. There was divergence of policy. Redmond wanted to support the war and, of course, Colonel Moore did too, but the Sinn Féin leaders wanted a more nationalistic programme. So great was the divergence of opinion that the two parties split.’21 Barton actually succeeded his cousin, Erskine Childers, as Colonel Moore’s secretary when Childers left the post to join the British navy.22 However, Barton did not remain long in the position either, as he mentioned in his witness statement:

I carried on until September, after the Sinn Féin Volunteers had broken off from the National Volunteers. I may have stayed on for about two months after the division. At that time, it appeared to me that the National Volunteers were rather a futile body and that I was not doing anything of much use. So, I went home to Annamoe after handing over to [Dermot] Coffey. It was in October, 1915, that I joined the British Army and went to train as an officer.23

On 17 December 1915, Captain Erskine Booth, who was stationed at the Curragh Camp, recommended Barton for a commission. Booth’s letter of recommendation was fulsome in its praise, stating: ‘I have known Robert Childers Barton all his life, and can conscientiously say that I know no man more suitable for a commission … [He] has given up a very large house and farm so that he may do his duty to his country.’24 This recommendation acknowledged Barton’s sacrifice in leaving Glendalough House and the family estate so that he might ‘do his duty’. This is the first overtly documented mention of what was to become a recurring motif throughout Barton’s long life – his sense of duty. It must surely have been a prime motive in his decision to join the British army during the war. Barton received his commission, and served as a second lieutenant in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. His brothers, Thomas Eyre and Charles Erskine, were officers in the Royal Irish Rifles. Both were killed in France – Thomas in July 1916 and Charles in August 1918.25 Fate, however, dictated that Robert would be gazetted and sent not to France, but to Dublin, in the spring of 1916.

3

An Easter Rising

(April 1916 and its Immediate Aftermath)

When Barton arrived in Kingstown (Dun Laoghaire) on the outskirts of Dublin on the Wednesday of Easter Week 1916, he saw that the city was ‘more or less under siege and part of it was in flames’.1 Barton was unable to travel into the city, so he reported to the Provost-Marshal at Kingstown, who sent him home because he had no uniform! Barton went home to Annamoe, where he remained for ‘about a week’, before returning to the capital to report to his commanding officer, Colonel Lawrence Esmonde of the 10th Dublins, in the Royal Barracks, as he had been originally ordered to do.2 Esmonde and Barton knew each other,3 and in a telling comment, Barton revealed that Esmonde ‘knew where my sympathies lay’, so he ensured that ‘my duties were confined to the barracks’.4 Barton’s sister, Dulcibella, maintains that Esmonde actually asked Barton, ‘Do you want to fight?’ to which Barton replied ‘No.’5 Esmonde may have been trying to ascertain whether Barton was willing to take an active role in rounding up and arresting suspected rebels and their sympathisers, as by this time the rebellion had been quashed, and many of the rebels had been taken prisoner. Rebels who had been captured at every volunteer position and nearly all of those arrested in the round-up of suspects following the rebellion (some 3,240 men and 79 women) were taken to Richmond Barracks in Inchicore.6 In fact, the barracks housed more than 3,000 suspected rebels before their sentencing.7 After a few days at the Royal Barracks, Barton was sent, along with Lieutenant Grant, to Richmond Barracks, to report to Colonel Frazer for ‘duty in connection with the prisoners’. Grant was put in charge of prisoners’ letters, and Barton was instructed to ‘take over the duties of officer in charge of prisoners’ effects’. Frazer told Barton that there were a great many charges of looting against the British troops, and the War Office had instructed the authorities in Dublin to stop the looting and to collect what had been looted and return it.8 Thus began Barton’s time spent with the rebel prisoners, some of whom he already knew from his time in the Volunteers – an experience that seems to have had a profound effect on him. Despite disliking his role in relation to prisoners’ effects,9 according to Pakenham, Barton was ‘profoundly moved by the faith and stoicism of the prisoners, [and] he came to see them as the representatives of the new spirit in the country, and to reckon it a crime to resist their movement further’.10

When he arrived in Richmond Barracks, Barton found things ‘in a chaotic state’. He found that ‘prisoners’ effects were in buckets and bags littered around the office’, and he ‘first tried to put them into order and to find out to whom the properties belonged’. He also noted that ‘the bundles had been systematically pillaged’. He set to work painstakingly, trying to restore order from the chaos and to return property to its rightful owners. He ‘went around to all the prisoners to ascertain what each had lost’ but he was ‘unable to return a quantity of property’ because he ‘could not find claimants amongst the prisoners in the barracks’.11 He also wrote to prisoners’ next of kin, relations and friends. One such letter was written to Mabel Fitzgerald, wife of Volunteer Desmond Fitzgerald, at Loretto Villas, Bray, County Wicklow, in which he informed her that ‘a great coat labelled as being the property of Mr Fitzgerald is being forwarded to you at the above address this day’. The letter was dated 21 May 1916 and was signed by Second Lieutenant R. C. Barton as ‘officer in charge of prisoners’ effects’.12 He soon found, however, that his rank of second lieutenant didn’t carry much weight when he was dealing with superior officers – Barton noted that a major could get information from them far more easily. Consequently, Colonel Frazer appointed Major Charles Harold Heathcote of the Sherwood Foresters to the role, leaving Barton in place to work under him in the prisoners’ effects department.13 This change is reflected in a letter written by Barton to Dr Kathleen Lynn, dated 11 July 1916. He informed Lynn that no action had yet been decided upon regarding property lost in Liberty Hall during the rising, but he assured her that her claim had ‘not been lost sight of’ and he promised to write again when he had the ‘necessary authority’. This letter was signed by Barton ‘pro officer in charge of prisoners’ effects’ [Heathcote].14 As was the case with the letter to Mabel Fitzgerald, the tone of the letter to Kathleen Lynn was polite and respectful, which one might not expect from an officer in Richmond Barracks in the immediate aftermath of the Easter Rising, considering that both women were directly and actively involved in the rebellion. It seems that the dutiful Barton did his job well and worked efficiently, whether under his own authority or under Heathcote.

Fig 3. Devastation greeted Second Lieutenant Barton on his return to Dublin in 1916. (Image (Barton Papers, WWCA/PP1/33) courtesy of the Wicklow County Archive)

Contact with Heathcote may also have contributed to Barton’s political awakening, which eventually resulted in his decision to join Sinn Féin. Heathcote served in the Sherwood Foresters, the regiment that took heavy casualties at and around Mount Street Bridge. Ostensibly as a reward for their gallantry (but in a move that smacked more than a little of taking revenge), the Sherwoods were chosen to form the firing squads for the post-rebellion executions. Brigadier J. Young was in charge at Kilmainham Gaol, but Heathcote, as second-in-command of the regiment, was in command of the actual firing squads.15 Barton referred to this fact in his witness statement, noting that:

Heathcote was in charge of the firing party at the executions in Kilmainham – at the execution of the first six or seven anyway. He was in charge of the firing party and … He was present at Connolly’s execution. He may have been in charge of all the executions.16

Heathcote’s role in the executions meant that he was uniquely placed to give Barton many of the gory details of the events in the Stone-breakers’ Yard at Kilmainham, where the grisly work of killing the condemned leaders was carried out. For example, Heathcote’s description of the execution of James Connolly seems to have left a deep impression on Barton,17 who deposed in his statement:

Heathcote told me he [Connolly] was probably drugged and was almost dead. He was not able to sit upright in the chair on which he was placed and, when they shot him, the whole back of the chair was blown out … They brought out a chair for Connolly because he was unable to stand. They brought him in an ambulance and from that on a stretcher to the chair. I think … they just laid him in the chair. They shot him through the chest and blew the back out of the chair. I gathered from Heathcote that he was quite unconscious. He was a dying man.18

Hence, although Barton did not witness any of the executions in person, the descriptions that he heard from Heathcote evidently stirred a degree of sympathy for the rebels within him. Barton’s presence at some of the courts martial held at Richmond Barracks in the immediate aftermath of the rising,19 including that of Seán MacEntee, increased his empathy with the prisoners.20 He testified in his witness statement:

I saw Seán MacEntee court-martialled. It must have been about the middle of May. I was present. Lord Cheylesmore presided at the court-martial. I don’t know whether Seán had a lawyer or not, but I know that it was a terrible ordeal for him … An officer – I think he was a Scots Guard – was called to give evidence and was asked, ‘Can you recognise any of your attackers’? He looked round and pointed to Seán MacEntee and said, ‘I recognise him’. I thought it was going to be very hot for Seán MacEntee, but he did not turn a hair …21

Despite the growth of his nationalist sympathies and the beginnings of a more radical shift in his political opinions, Barton remained in the British army until June 1918. The 10th Dublins embarked for France, crossing to Le Havre, on 19 August 1916,22