Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

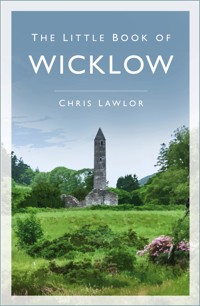

Did you know? - According to legend, St Kevin founded his monastery at Glendalough after being shown the spot by a goose. - A murder in the sleepy village of Barndarrig in east Wicklow in 1890 led to the last hanging in Wexford gaol. The Little Book of Wicklow is a compendium of fascinating, obscure, strange and entertaining facts about County Wicklow, the last Irish county to be created and one of the most beautiful, the 'Garden of Ireland'. From the stark grandeur of the Wicklow Mountains to the fertile coastal plains, this book takes the reader on a journey through the county and its vibrant past. Here you will find out about Wicklow's castles and great houses, its monastic heritage and heroic leaders. You will also glimpse a darker side to Wicklow's past with a look at crime and punishment and Wicklow's wicked women. A reliable reference book and a quirky guide, this can be dipped into time and time again to reveal something new about the people, the heritage and the secrets of this ancient county.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 209

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For my granddaughter Bronagh Rose Lawlor.

May you enjoy this book when you are old enough to do so.

Daideo.

First published 2014

This paperback edition published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place,

Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Chris Lawlor, 2014, 2022

The right of Chris Lawlor to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 6282 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Introduction

1. Monastic Wicklow

2. Wicklow’s Great Houses

3. Wicklow Rebels

4. Crime and Punishment: Tales from Wicklow’s Dark Side

5. Wicked Wicklow Women

6. Poor Parnell: Wicklow’s Wronged Leader?

7. Trial and Retribution: The Only Black and Tan Executed in Ireland

8. The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921: The Wicklow Connection

9. Wicklow on the Silver Screen

10. Wicklow’s Historic Towns

INTRODUCTION

Wicklow, a medium-sized Irish maritime county, 782 square miles in area, is unique, scenic and historic. Much of the interior of the county is made up of the large remote fastnesses of the Wicklow Mountains. These are some 500 million years old and were formed during the period of Caledonian folding, which produced the granite so synonymous with Wicklow today. Lugnaquilla, the highest mountain in the province of Leinster and one of the highest in Ireland, dominates the range, brooding silently over all else. Hill walking is popular in central Wicklow, but the landscape changes in both the east and west of the county. In the east, a fertile coastal plain provides an excellent location for the county’s larger towns, all of which have maritime locations. In the west, rolling hills produce an undulating landscape with a patchwork of fields and farms, as the landscape becomes lower and eventually tails across the county boundary into the great central plain of Ireland.

While the natural beauty of Wicklow attracts many visitors, the county’s heritage is also a significant factor for many tourists. There are many historic sites, such as Glendalough, Wicklow Gaol and the Dwyer-McAllister cottage, throughout the county. This book takes a look at some aspects of Wicklow’s colourful history. It focuses both on what happened in the county and on the exploits of some of Wicklow’s sons and daughters, many of whom excelled and were influential in various fields of human endeavour. The stories featured in this book range from the deeds of the great and the good to the misdeeds of the lesser and the bad. From saintly monks to vile murders, County Wicklow has seen it all over the centuries. Wicklow people have made history on land, sea and in the air, and this Little Book of Wicklow tries to capture some of that astonishing history. I hope you enjoy delving into the past of wonderful Wicklow!

1

MONASTIC WICKLOW

County Wicklow has no shortage of monasteries, abbeys and priories, but one site stands head and shoulders above all others in terms of its monastic significance. Glendalough was one of the most important monasteries in Ireland, and its monastic community flourished right through Ireland’s Golden Age, when the island was known as the Island of Saints and Scholars. This remote Wicklow valley was a huge centre of learning, power and influence during the early Middle Ages, both before and after the Norman conquest of Ireland.

GLENDALOUGH

Glendalough monastery lies in a glaciated valley, with its wide floor and steep sides. A waterfall cascades down from a hanging valley, flowing into a rock basin lake below. The name Glendalough actually means ‘the valley of the two lakes’: the rock basin lake has been divided in two by the alluvial fan below the waterfall. Hence Glendalough contains both an upper lake and a lower lake. The valley is set at the very heart of the Wicklow Mountains, and marks out the path of a long-vanished glacier as it travelled down from its birthplace in a corrie near the Wicklow Gap, and on into the lowlands beyond the village of Laragh.

ST KEVIN

The illustrious monastery sprang from humble beginnings. According to legend and folklore, St Kevin came from a wealthy and noble family of the Dal Mesincorb, one of the Irish royal tribes. He was a very solemn and pious youth who attended a well-known monastic school at Kilnamanagh, near Tallaght in County Dublin. Kevin desired from a young age to live in a place of solitude, where he could devote his life to God. He left Kilnamanagh and arrived in Hollywood in west Wicklow, where he established himself as a holy man. However, in order to escape the amorous advances of a local maiden named Kathleen, Kevin crossed the mountains, eventually arriving in the isolated and peaceful valley of Glendalough. According to the Irish annals, Kevin began his existence as a hermit in the valley about the year AD 530 by hiding himself in a hollow tree away from the gaze of others, to rid himself of all distractions. One would imagine that this wild man of the woods would be left severely alone, but this was not to be the case.

Kevin, it seems, worked a miracle by supplying milk for a herdsman’s sickly child and the herdsman told everyone about the remarkable occurrence. Kevin’s fame spread and he was recalled to Kilnamanagh by his superiors. He pursued further studies and was ordained by Bishop Lugidus. However, he pined for the solitude and simple life of Glendalough, and he eventually returned there, where ‘he founded a great monastery in the lower part of the valley where the two rivers form a confluence’. Kevin’s austere asceticism and general holiness attracted many followers, and the monastery began to grow. However, Kevin still yearned for solitude and so he left the running of the monastery to suitable men, appointing each of them to a separate religious position, before removing himself to the upper part of the valley of Glendalough to continue his hermit-like existence at Tempeall na Scellig, ordering his monks to leave him alone so that he could enter into a life of quiet contemplation and meditation while fasting in order to become closer to God. Kevin survived thus for a period of 7 years and, according to the Annals of the Four Masters, died on 3 June 618, aged 120 years (or 117 years if one reads the Annals of Ulster).

The great age attributed to Kevin is only one of a number of pointers which indicate that he was an extraordinary man. Legends abound regarding the saint and his holiness. From the very beginning, it seems, his life was punctuated by a number of remarkable and inexplicable occurrences, known collectively as the miracles of St Kevin. The first of these concerns the sudden change in the weather immediately following Kevin’s birth. The extremely cold winter weather stopped suddenly and the whole countryside was immersed in balmy, mild spring weather for a continuous period of 7 years. When the infant Kevin was baptised by St Cronan, twelve immaculate white angels surrounded the baptismal font. Each angel held a lighted candle, all burning much brighter than any earthly light.

Kevin’s choice of Glendalough as the site of his monastery is also the subject of a legend. When Kevin was looking for a site for his monastery, a goose flew in continuous circles around the valley of Glendalough to indicate the amount of ground that the local king should grant to Kevin for his new foundation. This is one of a number of legends in which Kevin is portrayed as communing with nature and having a special affinity with birds and animals. In fact, Kevin is something of an Irish St Francis of Assisi in this respect. Supposedly King Brandubh, when hunting a wild boar through the valley of Glendalough, came upon Kevin kneeling in prayer in the open, with many birds perched on his outstretched hands and arms. A similar story is told recounting how Kevin was at prayer one day when a blackbird landed on his hand and laid her eggs in his upturned palm. When the saint came out of his reverent trance-like state, he noticed the eggs and, rather than harm any of God’s creatures, he remained in the same position for a number of weeks until the eggs were hatched and the fledglings had left the nest. A statue of Kevin in the church in Laragh village shows him with the blackbird’s nest in his hand, recalling the episode.

Kevin was not quite so kind to all birds, however. He cursed the ravens of Glendalough and would not allow them to eat any meat during religious festivals and events held in his honour. The reason behind the saint’s curse on the ravens is lost in obscurity, but the motive for his silencing the skylarks of Glendalough has come down to us through oral tradition. According to folklore, the workmen building the cathedral of Glendalough were becoming tired, weak and sickly because they would rise with the lark and lie down with the lamb. This gave them a very long and heavy working day, as the larks rose very early in the morning, creating untold hardships for the craftsmen and labourers employed on the building. Kevin had sympathy for the men and their plight, so he pleaded with God not to allow the larks to sing in Glendalough. The Lord heard Kevin’s entreaty and granted his request, making the valley a place where, according to legend, no skylark ever sings. The opening lines of Thomas Moore’s poem, By that Lake whose Gloomy Shore (1811), refer to this legend:

By that lake whose gloomy shore, skylark never warbles o’er,

Where the cliff hangs high and steep, young Kevin stole to sleep.

Kevin’s love of nature was not confined to birds. Animals and even reptiles came under his spell as well. One legend recounts how Kevin was reading a valuable and rare vellum psalter when he lost his grip on the book and it fell into the lake below the saint’s resting place. No sooner had the book disappeared below the surface of the water, however, than an otter surfaced from the silent depths, bearing the psalter on his nose. When the grateful saint retrieved the precious volume, he found that it was bone dry, despite having been fully immersed in the water. In another legend, Kevin was bathing in the lake when he was attacked by a serpent. Although the reptile managed to bite Kevin, he came to no harm – his skin was not punctured and the bite did not hurt him in any way.

Kevin’s lakeside dwelling also meant that many legends regarding his daily journeys around and across the water were passed down orally through many generations. It was reported that Kevin, who used to say Mass in a small village on the far side of the lake from his own dwelling, often crossed the lake without using a boat – literally walking on water. On one occasion, he was praying and fasting at his cave during Lent when an angel appeared to warn him to move as a large rock was about to fall on his head. Kevin, however, refused to budge, as it would mean breaking his penitential Lenten observance, so the angel interceded with God on the saint’s behalf. When Kevin rose and walked across the water after sundown on Holy Saturday (the eve of Easter Sunday), the rock immediately fell, leaving churning water in the wake of the saint when it tumbled from the rocky ledge above into the still waters below.

Other legends about St Kevin abound. One of these concerns a visiting sick friend of the saint who had an unusual craving for apples, as he believed they could cure him. Apples were out of season, and there was no apple tree near at hand, but Kevin picked three luscious apples from a willow tree beside the lake, and when his companion ate them, he was immediately cured. Kevin’s generosity features in many of the stories, and in one instance the saint punished lack of generosity in another. One day he met a woman carrying a basket covered with a cloth. Kevin asked her what she had in the basket and the sly dame told the saint that she was carrying stones, as she did not care to share her bread with a hungry man. Kevin recognised the lie for what it was and he retorted that if she had stones they would turn into bread, but if she had loaves of bread, they would turn into stones. Dismayed and ashamed, the woman threw away the stones that were now weighing her down, and these round stones can still be seen on the south side of the Lower Lake, between the monastic site and Rhefeart.

Yet another legend tells of how, when the monks at Rhefeart church were singing a hymn to St Patrick, the abbot told them to sing the hymn again and again. When they had done so three times, he enlightened them as to the reason for his request. Apparently he had seen a vision of St Patrick standing over them and holding a bishop’s crozier while blessing the community during the singing. Visions of saints and angels were often attributed to Kevin, and when he eventually died it is said that hosts of angels filled the remote valley and lined up along the lakeside, singing and praising God. Pilgrims from all over Ireland and further afield who came to Glendalough in later times often wished to be buried in the shadow of the monastic ruins for the love of God and his holy angels as well as devotion to St Kevin himself.

MONASTIC RUINS

The monastic ruins in Glendalough are impressive indeed. Irish monasteries of the early Middle Ages were unlike the communal buildings of later medieval confraternities in continental Europe. European monks, who often lived according to the Rule of St Benedict, lived, worked and prayed together in one large monastery or abbey, but earlier Celtic Irish monasteries consisted of small individual dwellings. Every monk had his own small cell, and these were dispersed and dotted around with the churches and communal monastic buildings at the centre. Most of the buildings of the old monastery are no longer extant and the individual monks’ cells and the huts of masons, smiths and craftsmen are long gone. Most of these were constructed of wood or wattle and daub. Wattle was the name given to small saplings, usually of willow or hazel wood, interwoven horizontally around a series of vertical wooden stakes driven into postholes in the ground. Daub was a wet mud used as plaster, which was used to cover the wattle, fill the cracks and keep out draughts. When the mud dried, it hardened and created a weatherproof wall. However, in the long term, wattle and daub – like wooden buildings – proved susceptible to the ravages of the weather over many centuries, so these buildings no longer exist at Glendalough. What remains today are the ruins of the stone buildings that stood at the centre of the once-proud monastic city.

The monastic city was accessed via the great stone gateway. This consisted of two arches, both undecorated (about 9½ feet wide and 2½ feet thick), enclosing an interior gatehouse space of approximately 16 square feet. This was paved with large, rough floor slabs. On the right hand side as one enters through the gateway, one of the slabs in the side wall is decorated with a carved cross. This is where the pilgrim visiting the sacred city would be reminded that they were now entering holy ground. Touching this cross enabled them to, in modern parlance, ‘touch base’ with the Lord. The cross-inscribed stone in the wall is also known as the sanctuary stone, because fugitives from justice or those fleeing for other reasons could claim the protection of ecclesiastical sanctuary from the rigours of the law or their enemies once they stood on the holy ground within the gateway. The gateway had at least one upper storey, which served as a lookout point, while oral tradition points to there being a tower above the great archway. On the outside, opposite the gate, lay a paved roadway leading over the mountains and on to the ecclesiastical centres of County Kildare.

Within the sacred city, the most impressive church was the Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul. Originally named for the Sacred Heart, the cathedral was rededicated to the saints in the twelfth century. Though roofless and ruined, the building is still an imposing one, and evidently went through much refurbishment, remodelling and rebuilding. The chancel is a very fine example of Hiberno-Romanesque architecture. The decoration in this area of the cathedral dates from the ninth and tenth centuries, as does the east window, which was very finely carved, though exposure to the elements has caused much weathering over the centuries. The cathedral was built as a bishop’s church, from whence the cleric could speak ex cathedra to all in his diocese. Glendalough was a separate diocese in Gaelic Ireland, but after the Normans arrived in Ireland in 1169 they redrew the diocesan boundaries and Glendalough was united with the see of Dublin. This remains the case to this day, and the fact that the Roman Catholic diocese is still referred to as the see of Dublin and Glendalough provides some evidence of the former significance of this isolated and remote Wicklow valley, which is mentioned in ecclesiastical circles in the same breath as Ireland’s primate city of well over a million people.

The oldest church in Glendalough is known as the church of Our Lady or St Mary’s church, though it may previously have been dedicated to St Ifinus. Measuring approximately 32 feet by 20 feet, it is much smaller than the cathedral, reflecting perhaps the simpler architecture of an earlier stage in the history of the monastic settlement. As the monastery grew its power and influence increased, and when it became a bishopric there was a need for grander buildings. The oldest part of Our Lady’s church is the nave, so it was remodelled at least once. A stone altar with an ornamental slab above it, a holy water font and an inscribed cross on the lintel of the west door all bear silent testament to the religious services that once dominated life in this, the monastery’s oldest church.

Another feature of interest in the ecclesiastical site is St Kevin’s Cross. The high crosses of Celtic Ireland are famed far and wide for their fine stonemasonry. Many, such as the crosses at Monasterboice (County Louth) and Moone (County Kildare), are intricately carved and show scenes from the bible. St Kevin’s Cross is different. It is one of the earliest examples of an Irish high cross – it stands about 11 feet 4 inches tall – and one of the plainest. This broad, undecorated, heavy cross made of Wicklow granite traditionally marks the location of St Kevin’s grave, though some sources suggest that he was buried in Our Lady’s church. Although it is a Celtic cross, with ‘arms’ around the junction of the vertical and horizontal pieces, St Kevin’s Cross is unique in Irish monastic stonemasonry as the arms of the cross are not perforated. It has been suggested that these round arms on Celtic crosses are a throwback to ancient Celtic solar pagan rituals, with the arms representing the sun. However, the circular design may simply have been round buttresses to strengthen the stone crosses, many of which were tall and slim in their execution. According to folklore, anyone who visits Glendalough and who can stand with his or her back to the cross and join hands behind it will have a wish granted to them. As anyone who has ever tried it can testify, this feat is easier said than done!

Possibly the best-preserved building in Glendalough is St Kevin’s Kitchen. This church got its nickname from the round belfry, which looks like a chimney, and it is one of the oldest on the site. It dates from c. 533 AD and St Kevin supposedly lived here in his later years, after he left his hermitage in the cave known as St Kevin’s Bed, high above the waters of the lake. The chancel of the kitchen is no longer extant, but the nave measures approximately 23 feet by 15 feet. The roof is of stone, somewhat similar to earlier corbelled roofs such as that in the passage grave at Newgrange (County Meath), and there may have been an upper floor in the building at one stage. The belfry rises 9 feet above the apex of the roof and contains six small windows, four of which exactly face the cardinal points of the compass. The window in the southern wall of the kitchen was inserted at a later date, in the nineteenth century, when the building was again used for Roman Catholic worship in the post-Penal Laws era, and devotion to St Kevin was once again overtly demonstrated by Irish Catholics in pre-Famine Ireland.

The ruins of the Priests’ House are located just south of the cathedral. This was probably the mortuary chapel of the monastic community, and later priests of the local parish were certainly interred here. The building was originally part of the monastery’s cemetery, which was much smaller than the present-day graveyard. The Priests’ House is not in good repair and many stones are missing, but there is evidence of fine decoration on the east wall and window. In the west wall is the recess of the wishing stone, and the south wall contains an ornamental tympanum, depicting St Kevin between two bishops, one with a crozier and one with a bell. The crozier, or bishop’s staff, is a symbol of ecclesiastical authority and the message is clear – Kevin’s Glendalough is a bishopric of some significance and an important foundation in the Irish ecclesiastical world. The bell is associated with all monasteries and symbolises the call to prayer. Moreover, one of the most important relics associated with St Patrick is a bell, and the message may aim to show that the authority of Kevin’s Glendalough can be traced back to Ireland’s patron saint, and that the Irish hierarchy should recognise that Glendalough has great significance as an ecclesiastical site in its own right. The remains of no fewer than five churches – the Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul, the mortuary chapel of the Priests’ House, St Kevin’s Kitchen, the church of Our Lady and another church, that of St Ciaran (of which not much is extant), within the monastic city bear ample testament to that significance.

However, no building within the monastic city demonstrates this significance more than the round tower. It is in an excellent state of preservation and the top section, which was struck by lightening, was reconstructed with the original stones in 1876. Round towers are uniquely Irish landmarks, and they were erected in or near many monasteries. Their remains dot the Irish landscape today. Round towers began to feature prominently following the arrival of the Vikings in Ireland. The first Viking attack was on Lambay Island, off the coast of County Dublin, in AD