Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Rome in the 1950s: following the darkness of fascism and Nazi occupation during the Second World War, the city is reinvigorated. The street cafés and nightclubs are filled with movie stars and film directors as Hollywood productions flock to the city to film at Cinecittà Studios. Fiats and Vespas throng the streets, and the newly christened paparazzi mingle with tourists enjoying la dolce vita. It is a time of beauty, glamour – and more than a little scandal. Caroline Young explores the city in its golden age, as the emergence of celebrity journalism gave rise to a new kind of megastar. They are the ultimate film icons: Ava Gardner, Anna Magnani, Sophia Loren, Audrey Hepburn, Ingrid Bergman and Elizabeth Taylor. Set against the backdrop of the stunning Italian capital, the story follows their lives and loves on and off the camera, and the great, now legendary, films that marked their journeys. From the dark days of the Second World War through to the hedonistic hippies in the late 1960s, this evocative narrative captures the essence of Rome – its beauty, its tragedy and its creativity – through the lives of those who helped to recreate it.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 444

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

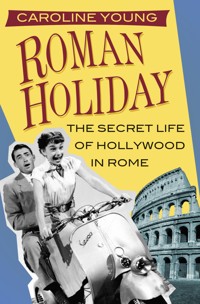

Cover illustrations: Front: Photo 12/Alamy Stock Photo. Back: Anita Ekberg. (Author’s collection)

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Caroline Young 2018

The right of Caroline Young to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-7509-8723-3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

1 ROMILDA

2 TENNESSEE

3 ANNA

4 INGRID

5 SOPHIA

6 AUDREY

7 AVA

8 AUDREY

9 SOPHIA

10 ANNA

11 AVA

12 INGRID

13 AVA

14 ANITA

15 ELIZABETH

16 BRIGITTE

17 SOPHIA

18 RICHARD

19 JANE

20 AUDREY

21 ELIZABETH

PROLOGUE

The outdoor cafés of the Via Veneto, one of the most exclusive streets in Rome, filled up early as well-dressed society people, starlets and tourists sipped on a Bellini or a Negroni beside the potted azaleas and tightly parked scooters that lined the pavement. By 7 p.m. the city was soaked in the last of the day’s sunlight, its golden domes glowing beneath the sunset as the scent of Coco Chanel and cigarette smoke drifted amongst the tree-shaded tables. Well-known faces were commonplace, and the chatter grew louder as the evening progressed, trying to be heard over the roar of traffic. The word on everyone’s lips in 1962 was the affair between Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton on the set of Cleopatra. Despite both being married, they flaunted their affair on the Via Veneto, the beating heart of Rome’s celebrity culture, in the elegant white tableclothed restaurants on colourful, lively Piazza Navona, looking out onto the fountain with its Egyptian obelisk, or they indulged in secret kisses in their dressing gowns on the Cinecittà backlot. All the while the relentless, cunning paparazzi came up with even more inventive ways of capturing the romance.

Movie stars like Elizabeth Taylor or Ava Gardner, beautiful, impulsive and living the good life, were easy targets for the press in Italy when away from the protective grip of Hollywood, and Rome had become a free-for-all. Back in the States, the studios could build their own myths around their stars which the American movie magazines would happily support, whilst press agents were used to being able to suppress the bad publicity. But in Rome the new wave of independent press photographers, ambitious self-starters who had no such loyalties and needed only a light 35mm camera, a Vespa and a good eye for a story, could sell the most scandalous photos to the highest-bidding publication. Suddenly, the stars of the screen seemed a little more human.

The photographers in their crumpled suits were stereotypically aggressive and rude and whilst it wasn’t until 1960, with the release of Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, that they would collectively be known as ‘paparazzi’, they were a common and feared sight for celebrities around Rome. Tazio Secchiaroli, Velio Cioni, Elio Sorci, Marcello Geppetti – these were some of the photographers who ‘must be seen in action to be believed’, as an American journalist in the late 1950s noted. Using twin-lens Rolliflexes with a hand-held flash, they had to get as close to their subjects as possible, and this created the startled shots that were so typical of the era. After they had taken snatch shots, the photographers would go to the telephoto window at the central post office in Piazza San Silvestro and they would pay $20 to develop their film and send the images to Fleet Street in London as exclusives.

The happenings of Rome could be relied upon to fill the papers in every country on every day of the week, whether it was fights, secret weddings, public break-ups, or even murder trials, like that of Wilma Montesi. She was a young woman whose body was found on a beach near Rome in April 1953. Her death was linked to the upper echelons of society, and the secretive drugs and sex parties of society people and politicians. Life in Rome seemed more dramatic than the movies themselves.

La dolce vita grew out of the ruins of post-war Italy, where the glamour of celebrity offered a much needed escape from the memories of the bombings, the food shortages and of a country very much at breaking point. And it was Italian actresses, as well as Hollywood stars, who would be at the vanguard. Producers Carlo Ponti and Dino De Laurentiis invested in Italian cinema and multinational productions, pushing up the reputation of Italian-made film.

In the 1950s, Rome had become a place where people could finally celebrate the good times following the Second World War, and when the international film studios began to use Cinecittà for their sword and sandal epics, along came the Hollywood stars to enjoy their drinks on piazzas, the sun sparkling on the water as it splashed from ancient fountains surrounded by ancient symbols of its former empire. Parties took place across Rome in penthouse hotel rooms, rooftop terraces with views of terracotta tiles and shimmering renaissance domes, ivy-covered villas along the Appian Way and artist’s studios in the bohemian Via Margutta. But the centre of celebrity life was the Via Veneto, which since the end of the Second World War had become Rome’s fashionable street, defined by new notions of fame as cinema stars, tourists and the press collided. People spilled out into the street and rested under the parasols of the outdoor tables, almost like it was a ‘seaside resort’, as Ennio Flaiano observed in 1958.

By the mid 1950s the three blocks of Via Veneto situated between the Aurelian Wall and US Embassy had become an exclusive strip of luxury hotels, clubs and cafés populated by the rich, the famous and the fame-hungry. The notable sights included the Hotel Excelsior, the Café de Paris, the Bar Rosati, Harry’s Bar and the all-night drugstore L’Alka Seltzer. Bricktop, owned by the legend of 1920s Paris, Ada ‘Bricktop’ Smith, was fashioned like a prohibition-era drinking den, creating a sense of the illicit with jazz music and cigarette smoke seeping out of it, its glamorous aura drifting out into the street.

If Italian cities like Milan and Rome were gradually embracing the economic boom of the 1950s, then the Via Veneto was the heightened symbol of the new affluence. Traffic clogged the streets as Fiats, horse-drawn carriages, Vespa scooters, taxis and buses all travelled up and down this half-mile stretch. It was here that you could see Clint Eastwood skateboarding down the road, Anita Ekberg drunk and barefoot, Jayne Mansfield eating spaghetti, or the early sixties chi-chis with their animal-print coats or their tamed leopards on a lead. It was the glittering, hedonistic heart of Italy, where the wealthy and connected could congregate before heading off for romantic weekends in a smart hotel on the Amalfi coast or to find some respite on a yacht moored off the Isle of Capri.

The 1940s and 1950s was considered ‘the Flash Age’ of agency photographers whose close-up images created a sense of reality, a moment captured in time, rather than the atificiality of posed photos. However it was in the 1960s, the Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor era, where the telephoto became more common. Taylor and Burton marked the modern era of celebrity, of packs of paparazzi, long-lens snatch shots on the front pages of tabloids and illicit love affairs. Their extravagant lifestyle was firmly played out in public, travelling the world with an entourage and where Rome served as a base for their fast, expensive life. Elizabeth collected expensive jewels, they holidayed on yachts with Onassis and held Paris dinners with the Windsors and Rothschilds. The grainy photos taken from the shoreline while the rich and famous frolicked and sunbathed on the deck of their yachts became a mainstay for photographers of that era.

But what really defined the paparazzi was the way they created the story by triggering their subjects. Photographers realised that an action photo of a celebrity under attack or being chased made a more valuable picture than those posed photos outside cafés. It became a game, of provoking the stars to react – of sneaking into Cinecittà and hiding in boxes or under cars, of climbing into the trees around Elizabeth Taylor’s pool to find that lucrative shot. The photographers were mostly poor young men who found a way to make money and to feed their family, and their subjects were the rich and famous – illustrating the gap in wealth of the era. And with a never-ending stream of famous faces drifting into view, Rome was ripe with opportunities.

In the 1950s, it was advantageous for Hollywood to film overseas, where they could access their frozen profits in local currency, and where they could fully promote exotic scenery with widescreen and Technicolor formats. At the time, anyone living out of the States for eighteen months at a time would also avoid paying tax. So here you would find Ingrid Bergman, under self-imposed exile after coming to Rome for love; Audrey Hepburn, who represented joyful holidays in the city in the early 1950s; Ava Gardner, whose tempestuous love life and appreciation of the nightlife always served for a good photo; Elizabeth Taylor, the queen of Hollywood excess and jet-set lifestyle; and Anita Ekberg, the face and body of la dolce vita. Sophia Loren was the home-grown star who captivated Hollywood and who represented the struggles and dream of young girls who survived the Second World War and lived through Rome’s 1950s recovery, and Anna Magnani, the icon of Italian neorealism and one of the most admired, revered women in the country.

1

ROMILDA

Like many young girls growing up after the First World War, Romilda Villani dreamt of experiencing the glamour and excitement of the movies. She was from the small fishing village of Pozzuoli, 25km along the coast from Naples and built on the volcanic rock of the mighty Vesuvius. It was a place of myth, the location of the entrance to Dante’s inferno, where the sea crashed against the rocky cliffs during stormy winters and where residents could feel the shuddering movement under their feet from the magma flowing beneath them.

Romilda had the enigmatic beauty of Greta Garbo, the most popular movie star in the early 1930s. She plucked her eyebrows into Garbo’s crescent shape, wore her hair shoulder length and with a side parting just like Garbo, and owned a camel-coloured coat that she could wear the Garbo way, with the collar turned up. Such was the similarity that people even stopped her on the street to ask for her autograph. Romilda was also a talented pianist, having studied piano at Naples’s conservatoire San Pietro a Maiella, and she could dance, which surely put her in a good standing for going into show business.

When the American film studio MGM held a contest in 1932 to find the Italian Garbo, 17-year-old Romilda jumped at the chance to enter, and she won the prize – a ticket to Hollywood to take a screen test at MGM. It may have been her dream come true, but her mother refused to let her daughter go overseas. America was too far away and too dangerous, and Romilda was too young.

Despondent at not being able to go to Hollywood, she walked along the waterfront of the town she had grown up in, dreaming of her escape to Rome, the next best place to go to after America. Romilda had heard that aspiring actresses could be discovered in the capital. At this time, in the early 1930s, the cinema was one of the few ways for finding fame and fortune. Once Romilda had saved enough money from playing and teaching piano, she bought a train ticket and headed for the eternal city. The Rome she arrived in was under the leadership of Benito Mussolini, who had ambitions to create a new Italian empire.

Mussolini and around 30,000 of his Blackshirts marched into Rome in 1922 and he was quickly given power by King Victor Emmanuel III to form part of a new coalition government. His promises were as authoritarian as the manner of his arrival, with emphasis on law and order, the promise of more rights for war veterans and above all the burning desire to create a stronger nation. He was a ruthless man, and by 1925 he had seized complete power, creating a police state and purging the country of all opposition. As part of Mussolini’s new plans, Rome would be a beacon that shone across Italy.

But an awe-inspiring city needed a large population, and from 1920 to the mid 1930s the population of Rome doubled to over 1 million people as he encouraged citizens from across the nation to migrate to the city. With the huge increase in population came domestic challenges, and there was a housing shortage as families were crammed into apartments. When Mussolini’s plans for fascist Rome were officially adopted in 1931, they involved measures to address the population swell: the creation of new expansion zones and a modern rail network, hospitals, schools and covered markets. New housing projects sprung up during the 1930s, creating communities in apartment blocks on the outskirts of town, which lost a degree of connection with the historic past of the city. The implementation of the new Roman city plan was considered by Mussolini to be a ‘bloodless battle’ which would start ‘the fatherland towards a brighter future’. Il Duce ordered ground to be cleared to create a highway through the ancient city, linking it to the Piazza Venezia where he could stand high on his balcony, delivering his speeches to the crowds below.

Mussolini also had a keen interest in cinema. Italy in the thirties was the world’s third largest exporter of films despite the dominance of American studios and the challenges that came with the introduction of sound, as new technology had to be developed accordingly. When Mussolini came to power, his plan was to completely reinvigorate film-making as a tool for propaganda. ‘Cinema is the most powerful weapon’ was Mussolini’s slogan as he pushed ahead for an Italian film centre. He saw film-making’s power to influence the population, as Hitler and Goebbels had managed to formidable effect in Germany.

He introduced the first Venice Film Festival in 1932, founded the Centro Sperimentale film school in 1935 and his next plan was to create a studio centre in Rome which could compete with Hollywood. Cinecittà, or ‘cinema city’, was officially opened to great fanfare by Mussolini in 1937. Despite its later reputation as a propaganda machine, Cinecittà churned out 279 films from 1937 to its temporary closure in 1943. Out of this number were 142 historical films, 120 comedies and 17 propaganda films such as Scipio L’Africano, which justified Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia. Just like in Hollywood films of the same era, there was a fashion for movies showing the dreams of the poor, with lonely shop girls finding love and rising up the ranks, or epic historic dramas that told tales of ancient Rome. Popular ‘Telefoni Bianchi’ films were light-hearted comedies set in lavish drawing rooms and with conservative values to appease government control. In 1941 alone, 424 million cinema tickets were sold in Italy.

But in 1933, when Romilda was looking for work, Cinecittà Studios was still to be built. She found a job at a variety show at the Adriano theatre, and where she dressed in a costume like that of Garbo in Queen Christina, the sixteenth-century Swedish queen. In her free time, she strolled in her camel coat, turning heads with her movie-star appearance as she browsed the shop windows in the elegant Prati district. One evening in the autumn of 1933 Romilda was walking on Via Coli di Rienzo when a handsome, charming and aristocratic-looking man called Riccardo Scicolone sparked up a conversation and told her he was in the film business. He asked her out on a date, and Romilda was pleased that she not only had someone she could spend time with in the city, but who had promised to help champion her career. In reality Riccardo was poor and unemployed despite having claim to an aristocratic title, and was more suited to ingratiating himself in the world of show business and meeting young and beautiful starlets like Romilda. As was the fate of many girls at the time, she was seduced and then abandoned. A month after their first meeting, she broke the news to him that she was pregnant, and he wasn’t quite so keen anymore. The heartbroken Romilda gave birth in the ward for unwed mothers at Rome’s Santa Margherita hospital on 20 September 1934, putting an end to her dream of stardom.

Romilda’s baby was named Sofia, and was, according to the woman she would become, ‘frail and not particularly pretty’. Nevertheless, she would grow into the icon Sophia Loren – with the spelling of her name slightly changed – and while her birth put an end to her mother’s dreams of stardom, Romilda would later dedicate herself to her daughter’s career.

... according to the woman she would become, ‘frail and not particularly pretty’.

Riccardo had no intention of marrying Romilda – he was a lothario with his sights set on many other women – but he visited his baby in the hospital and gave her his surname, Scicolone, which made a big difference to Sofia’s legitimacy. It was better an absent father than no father at all on the birth certificate.

Romilda moved into a little pensione in Rome, occasionally leaving Sofia in the care of her landlady while pounding the pavements looking for work. As she was living in Rome on her own, she didn’t have older family members to advise her on how to care for the child. When Sofia became sick with enterocolitis, a doctor advised her that a warmer climate would be beneficial. It was now December and Rome’s warm autumn had given way to a cold winter.

Romilda returned to Pozzuoli, despite the shame of being an unwed mother and the guilt of ruining her family’s reputation; Sofia was so sick that she was close to death, and Romilda needed her family’s help. She and Sofia were back in time for Christmas, and as soon as she arrived at the doorstep her parents, Luisa and Domenico, welcomed her with an embrace, and the local wet nurse was sent to feed up the baby. With eight people crammed into 5 Via Solfatara it was a full house, but it had a view of Pozzuoli’s Roman amphitheatre from the kitchen window, while a balcony looked out over the gulf of Naples.

Grandma Luisa cared for Sofia while Romilda played piano in the cafés and trattorias of Pozzuoli and Naples. Sometimes she would visit Rome to meet up with Riccardo in the hope that she could persuade him to marry her. Following one trip to Rome in 1937, she came back pregnant by him once again – yet still she remained unmarried.

As Sofia grew older and went to school she began to feel embarrassed about not having a real father; even though her grandfather Domenico had taken on the role, everyone knew the reality. Sofia had big dark eyes and a shy smile, and she was given the nickname Toothpick because she was so skinny. Her thin arms and legs were made all the more so by the lack of food during the war, which broke out when Sofia was 6 years old.

The threat of war had been bubbling under the surface of Europe throughout the 1930s as the fascist governments of both Germany and Italy had ambitions to create their own empires through aggressive foreign policy. By 1936 Mussolini had fought and gained controlled of Ethiopia during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, and he had his sights on spreading out the empire across the Mediterranean and North Africa.

Germany and Italy, with their shared ideology, signed a Berlin–Rome axis treaty and Italy exited the League of Nations. With this formation of an alliance with Hitler, war in Europe was inevitable for Italy. Mussolini thought the war would be over quickly and believed that once the Allies were defeated he would be able to move in on French and British colonies in Africa.

What had been promised by Mussolini before entering into the war on the side of Germany failed to come true, and his plans to create a proud new section of the city – EUR – which harked back to ancient Rome fell to ruin at the start of the war.

Italy was a country with an economy still based on agriculture, and it was quite unprepared for the requirements of battle on multiple fronts. The 1939 invasion of Albania had weakened the Italian army and their artillery and tanks had not advanced in technology since the First World War. Mussolini pushed forward in North Africa with plans to invade Egypt, but the British held their ground and pushed them back into Libya. When Italy invaded Greece from Albania, they were supported by German troops to hold off the British. Winston Churchill warned that if Athens or Cairo were damaged by Axis powers then Italy would face strong retaliation on Rome despite its ancient treasures and sanctity of the Vatican.

For Romilda and Sofia the war first seemed far away, with the first effects a trickle-down of food shortages and gradually-growing austerity measures. But then the bombing came to Pozzuoli as the Allies targeted the Port of Naples from 1940. With the sound of the air raid siren Romilda and her family would rush out of their house to find cover in the cavernous railway tunnel on the Pozzuoli to Naples line, which was also a target for the Allies. They placed their mattresses down on the gravel next to the railway tracks, and would spend hours in the dark tunnels listening to the scuttling of mice and cockroaches, the sound of airplanes roaring in the sky and the falling bombs. They had to be out of the tunnel before the first train of the day at 4.10 a.m. and during one of these scrambles Sophia tripped and fell and hit her chin on rocks, leaving a scar.

It was cold and draughty in the tunnel and the girls didn’t have coats, so Romilda sacrificed one of her prize possessions, her camel coat, cutting it up and making it into two little coats for her daughters. Romilda would also take her girls to visit a friend of one of her brothers, a goat-herder who lit a fire in one of the volcanic caves along the coastline and who would give the girls a cup of nourishing goat’s milk, so fresh it was still warm.

As the bombing intensified across the country transport links and water mains were destroyed, resulting in a shortage of food and water. By 1942 popular support of the war was declining. With the country close to breaking point, the Allies invading former Italian territories in North Africa and the potential invasion of Sicily, Mussolini was forced to resign by King Victor Emmanuel in 1943, and went into hiding before being shot by Partisan rebels. Desperate for an exit strategy, the new Italian government held talks with President Eisenhower and an armistice was signed with the Allies on 9 September 1943. As soon as Italy effectively switched sides, the Germans tightened their grips on the population.

Sofia saw the Germans in Pozzuoli as they marched in unison through the town. They seemed harmless to her eyes, but then she would overhear her grandparents discussing the deportations of Jews, the torture and the fears they had of what happens next, and she knew that these soldiers weren’t as harmless as they seemed. In the summer of 1943 Pozzuoli was evacuated and residents were transported by train to Naples. The Villanis stayed with friends in Naples, but there were even more food shortages and limited water supplies. Sometimes Romilda would take water from the car radiator to give to her daughters, or she would beg for pieces of bread. Maria caught measles and typhus fever.

By September 1943, the Germans had marched into Rome, which fell without a struggle and was declared an Open City. For the next nine months Nazi soldiers terrorised and intimidated Rome’s citizens, setting up a command centre near the Villa Borghese and at the Excelsior Hotel, on the Via Veneto, where the top officers, led by General Kurt Malzer, stayed. They held grand luncheons while 1000 Roman Jews were deported to Auschwitz over the 270 days of occupation.

The Allies fought their way up from southern Italy and swept into Naples in October 1943, and Rome was liberated in June 1944 – the first of the three Axis capitals to be taken, marking a significant victory in the war. The first to march into Naples were the Scottish regiments in their kilts, followed by the American GIs, who paraded down Via Toledo, and the crowds cheered for they knew that with the soldiers came powdered milk, coffee and white bread. The GIs gave out chocolates and chewing gum to the children as they swept into town. ‘The Allies handed out real food – even white bread, which was a real luxury for us – and the farmers, little by little, began to cultivate the land again,’ remembered Sophia Loren. ‘But when winter came, the cold took our breath away … we’d all stay close together in the kitchen, the warmest room in the house. But outside, the world was still a daunting place.’

The Second World War had turned out to be more desolate and destructive than people could ever have imagined and as the capital, Rome was particularly dazed by war for years afterwards.‘The Rome of today is much changed from its pre-war self and the returning tourist – if such there were – would find many surprises,’ The Times reported in February 1946. ‘It is a city degraded and demoralised by the stress of war and defeat and foreign occupation, in which the stately beauty of its monuments and palaces tend to become obscured by an oppressive consciousness of the hard facts of life.’

Rome was a shell of what it had been before, its bombed-out streets filled with rubble. Instead of a carpet of wish-making coins, empty ration tins littered the basin of the Trevi Fountain, which had been turned off for the duration of the conflict. Under the threat of air raids, the city’s historic sites, including Trajan’s column, had been protected through the war years by bricks and concrete, which had been built up about them and were now slowly being taken down. Gas and electricity were in short supply, so cooking was carried out on charcoal or with cast-iron grates for cooking stoves, and candles and lamps used for lighting when the electricity failed. It was a tough existence, where even an apartment’s water supply had to be carried up the stairs in buckets.

The hardships of the war resulted in a new type of film-making known as neorealism. The gritty genre was born from necessity due to the closure of Cinecittà after it was stripped of all its equipment by the Germans, and then turned into a centre for refugees and displaced people. Director Roberto Rossellini had begun preparing Rome, Open City shortly after the liberation of Rome in June 1944, but with no film industry left, everything had to be improvised and self-funded. The film was written in a week, and had a documentary style due to the shortage of film stock. People living in the poorer sections of the city were hired as actors, or lent their homes for interiors and helped behind the scenes. It was this authenticity that made the film such a success, with The Times hailing its depiction of Rome. ‘The people are so tired, the tenements are so crowded, the children are so unruly; nerves are frayed, and the shadow of Germany is everywhere, but out of their last reserves of courage and strength men and women find enough courage to comfort one another and confound the Nazi-Fascist enemy.’

Roman actress Anna Magnani was named Best International Actress at the Venice film festival in 1947 for the role of Pina in Open City. Magnani’s powerful scene as she runs after the truck taking away her partner, only to be shot dead by Nazi officers, stayed with the audience long after the film finished. Magnani recalled how the famous scene was filmed with real German prisoners of war playing the guards, with their own machine guns over their shoulders and wearing their own boots that crunched into the ground as they walked. It was as intense as could be without being a documentary.

Following Rome, Open City’s success, Vittorio De Sica’s 1948 film The Bicycle Thief was also filmed on the streets of Rome and was similarly peopled with a cast of non-professionals. It showed a city that was not only physically damaged by war, but emotionally damaged too. It was something of a paradox that, whilst Italy as the subject of neorealist film was exhausted and broken, the films themselves were rapturously received, bringing Italian cinema into a recovery period.

Sofia was 11 years old when the war ended, haunted by the horrors and still the little toothpick from the lack of food during the conflict. Romilda began playing piano again in a Naples trattoria filled with American soldiers, with Sofia’s sister Maria belting out songs as accompaniment. Because the GIs enjoyed the performance so much, they were invited to their home on Sundays to sing along to Romilda playing Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald while they were served home-made cherry brandy.

At the end of the war the cinemas reopened and 11-year-old Sophia would go to the theatre to watch American films like Duel in the Sun with Gregory Peck or Blood and Sand with Rita Hayworth and Tyrone Power, one of the most handsome of on-screen lovers. In cities like Naples and Rome, suffering from food and clothing shortages, the cinema and the dance hall offered an escape from the drudgery of life.

By the spring of 1947 Sofia was maturing and her appearance had started to change: she seemed to grow into her large brown eyes, wide mouth and high cheek bones. She found herself the object of sometimes unwanted attention when she walked down the street – like for many girls, it was a shock to be suddenly stared and whistled at in the street while still very much feeling like a child. Even more of a shock was when one of her young teachers asked Sofia’s family if he could marry his pupil.

Once a month Sofia would be treated to a trip to Naples for a chocolate drink with whipped cream and a sweet, doughy sfogliatella pastry at a famous chocolatier called Caflish. It was here that Sofia saw Rome’s iconic actress Anna Magnani for the first time – broodingly staring down from a poster at a theatre where she was performing. She would have a huge effect on the young toothpick. For Sofia, the Rome of Anna Magnani and the movies would be a place she would soon be heading for herself, a fatherless child trying to make it as an actress and a star, who would be one of the central stars of a new age of celebrity journalism and paparazzi. Soon, Romilda and Sofia would travel to Rome together themselves, in order to help Sofia build her career.

2

TENNESSEE

Gradually sloping downhill from the gardens of the Villa Borghese to the Piazza Barberini, the tree-lined Via Veneto was built on the grounds of the Villa Ludovisi – an eighteenth-century park decorated with statues and fountains, flowered fields and pine trees, which had inconceivably been flattened in 1887 in order to create the solid stone apartment blocks of the Ludovisi neighbourhood and to build a palace for Princess Margherita of Savoy, King Victor Emmanuel’s mother. The palace became the American Embassy after the fall of the Royal Family in 1946, and was used as a centre for the Allied forces as a new Italian government was formed.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, the Via Veneto was occupied by popular trattorias and shops, which drew in an eclectic crowd to its bookshops and cafés. It was where you could play a leisurely game of boules in the afternoon, browse Libreria Rossetti, the city’s most prestigious bookshop and discuss politics with the intellectuals at Caffe Rosati, opened in 1911. But it was the fascists themselves who helped designate the Via Veneto as the place to be seen, with the construction of large marble buildings for government offices and hotels that were in easy reach of the outdoor cafés. In the 1920s and 1930s Mussolini’s son-in-law Galeazzo Ciano enjoyed an aperitif or two at the bar of the Hotel Ambasciatori, while the Grand Hotel was built in 1927 by Mussolini’s favourite architect, Marcello Piacentini. As the Via Veneto gained a reputation as the voguish street, the ‘gaga’, or Italian dandy, would come there for drinks after the horse racing where they could mix with Italy’s movie stars like Alida Valli and Clara Calamai.

After Italy declared war, the Via Veneto became more of a practical base. Farmers planted cabbages, tomatoes and onions in its flowerbeds, as part of Italy’s ‘grow more food’ campaign, and then the luxury hotels became the headquarters for the Axis powers. After Rome was freed and the Germans driven out, the US army moved into the hotels instead. The Hotel Excelsior, which was nicknamed Rest Camp, was where many GIs took their first bath in years in the hotel’s plush marble bathrooms. General Mark Clark still had his office there when the first tourists arrived again.

With American GIs inhabiting the post-war city, a new economy developed around their large pay packets and expendable income. Not only did they discover the joys of pizzerias, but a red-light district sprung up around the Spanish Steps. Italian women went crazy for the Americans, many leaving the country to go over to the states as post-war brides. Some poor young Italian men found work as scattini, or street photographers, who lingered around train stations and tourist sites looking for American soldiers or tourists to take a snapshot of. After posing for a photo, the GIs were given a card with details of where they could pick up their photo. The scattini would then develop their rolls of film in improvised darkrooms set up in old apartments in the historic quarter with the hope that their subject would turn up to pay for the photo. Over time there were fewer and fewer American GIs on the streets, as the city opened to tourists fascinated to see the ancient treasures and charms of a city that was recovering after having been brought to its knees. The street photographers now used their tricks on the tourists, and they could earn just about enough to live by taking their photos by the Colosseum or at the Pantheon. Some of these scattini would later use their skills as photo-reporters, and would find celebrity photos to be particularly lucrative.

Gathered again on the Via Veneto was a group of liberal Italian writers and journalists, including Ennio Flaiano, a friend of director Federico Fellini, who met up at the cafés of the Via Veneto, where they would discuss politics, films and books into the early hours. Flaiano remembered the smell of warm brioche in the air, how they could bicycle on the street on warm days, the breeze rustling through the plane trees that lined the street.

In Italy in the early 1950s less than 8 per cent of homes had electricity, drinking water and indoor plumbing, and more people worked in agriculture than any other sectors. Only a few years before sheep would still graze around the Pantheon, as shepherds moved their flock from the hills to the warmer lowlands. But Rome was changing. There was a sense of hope in the air as Italy tried to forget the pain and the humiliation of Mussolini’s broken promises. An increased number of cars were one of the first signs of this new prosperity as they travelled out of the city at the weekends, but the city was becoming infiltrated by scooters – lightweight Vespas and Lambrettas that made it easy to travel between neighbourhoods. Young people took their holidays at the beaches of Ostia and Fregene, travelling there by tram or car and bringing paninis for their snacks, or they could enjoy seafood being caught at the beach and brought straight to their table. At weekends the scattini would also travel by scooter to Ostia to sell photos to the families and couples enjoying a break by the sea, eating watermelon or ice cream from one of the beach vendors.

Many young girls lived in a half-fantasy life. They admired the window displays of the elegant shops on the Via Condotti, or they could go dancing at one of the floating piers along the Tiber with their coloured lights and straw roofs. They dreamt of the magical existence they saw on screen or in magazines and, like Romilda more than a decade before, hoped they could be discovered by the film industry.

In Vittorio de Sica’s 1948 film The Bicycle Thief, the lead character, Antonio, is putting up a poster of Rita Hayworth in Gilda the moment his bicycle is stolen. It was De Sica’s comment on the gulf between neorealism and Hollywood, but soon the two industries would blend together. As Italy’s post-war film industry flourished, Hollywood lured Italian stars to Los Angeles, where they swapped war-torn Rome for a home with a pool in the Hollywood hills as the countries began to combine their film-making talents. Alida Valli was signed by David O. Selznick and starred in Hitchcock’s The Paradine Case in 1946, while Valentina Cortesi and handsome Rossano Brazzi, who would play the lead in 1954’s Three Coins in the Fountain, also tried their luck in Hollywood. And in return, the reputation of Rome’s new studio facilities began attracting more and more Hollywood people to the city. Production companies could reclaim their funds that had been blocked from leaving the country before the war and take advantage of favourable exchange rates by working at the recently re-opened Cinecittà Studios.

In September 1949, the New York Times announced:

Postwar Italy is playing ‘Hollywood’ to more American film notables than ever before. Movie-makers or stars, they are finding Italy and her sun both a stimulating workshop and a pleasant vacation spot. For producers, part of Italy’s lure has been the unblocking of frozen Hollywood funds. But part, too, has been Italy’s own resurgence in film production. With such films as Open City, Paisan, To Live in Peace and Shoeshine having received world-wide acclaim. Whatever the reasons, Rome is today being referred to as Hollywood on the Tiber.

By 1948 Hollywood stars like Tyrone Power gathered at the tables on the Via Veneto if they were in town to work on a movie. Power flew into Rome on a goodwill trip in his own plane after being hailed as a hero during the war, and he really captured the imagination of the Italian public. Riding his big American open-top car along the Appian Way and past the Roman Forum he drew gasps from glamour-starved Roman girls, anxious to glimpse this handsome and toned star on the Via Veneto.

It was here that Tyrone met actress Linda Christian and they married in early 1949 – the first fairytale wedding after the war, which received front-page news and magazine spreads dedicated to capturing all the details for their readers. They married at the tenth-century Church of Santa Francesca Romana overlooking the Roman Forum, which was filled with a sea of white roses. Riot police were drafted in to hold back the screaming fans. Images of Linda Christian in her Fontana-designed wedding gown emerging from the chapel were syndicated around the world, with the ancient city in all its resplendent glory. In the words of photographer Jean Howard who covered the event for Look magazine, it was ‘the international social event of its time’. The wedding marked a new, more relaxed way of life in Rome after the hardships of war, creating an atmosphere in which the whole city could celebrate together.

The Hotel Excelsior rebuilt an annex and opened the Doney café, with its sidewalk area seating up to 400 people, which became a popular meeting place for Americans in Rome. Little round tables and chairs were lined up at the side of the building and out onto the pavement, and where the smart set would enjoy a ringside seat to see and be seen. Indeed, in 1948 Tennessee Williams described the Doney as ‘the fashionable sidewalk café in front of the fashionable hotel Excelsior’. Inside the Excelsior, the American bar was nicknamed The Snake Pit as it was where many movie deals were signed.

Aldo Fabrizzi, from Open City, met actress Jennifer Jones on holiday during a dance in Rome. Greta Garbo was spotted on a sightseeing tour, with plans to appear in a film called Love and Friend – which would have been her first in eight years if she had decided to return to the screen. Garbo was reported to have tried three hotels in five days in Rome, with none pleasing her, until she settled on the Hassler, where she was spotted emerging from its revolving doors in sunglasses and a large floppy hat. Montgomery Clift was photographed in Rome during a tour of Italy in 1950. He played with children in the garden of the Villa Borghese, wandered the streets with his camera around his neck, sunbathed on a parkbench, and in Milan he met director Vittorio De Sica, who had made such a big impression with The Bicycle Thief.

Count Giorgio Cini, president of the company that owned the Excelsior Hotel and the Lido in Venice, fell in love with Hollywood beauty Merle Oberon. The two carried out a whirlwind European romance in Rome, Venice and the French Riviera, and created a stir because he was still married, and she was twice divorced and seven years older than him. In September 1949 the 31-year-old Count boarded his private plane in Cannes, saying goodbye to Merle as he went to Venice for a trip. But as the plane circled low so he could wave farewell to her once again, the wing suddenly dipped and it crashed to the ground, killing him on impact. Merle, who fainted on witnessing the tragedy, was said to be inconsolable.

Betty Eisner, a Red Cross nurse during the war, and later a pioneering psychologist, travelled across Europe to document its recovery through the eyes of a tourist for the Los Angeles Times. In Rome in April 1949, she observed that the Via Veneto was ‘the winter capital of Hollywood. I can’t tell you how many American, Americo-Italian and Italian films are being made here just now, and the Excelsior Hotel looks like a combination of Mike Romanoff’s and the Bel Air.’ She observed the city full of students, reporters and tourists, those who at first were taken aback by the late serving time of dinner, the way one had to haggle at markets and the contrast between great wealth and abject poverty. They were charmed by the groups of nuns, priests and monks gathered on the streets, the stray cats mewing for scraps of food, the quaint horse carriages carrying tourists around Rome and on the Island of Capri.

In contrast to the poverty of many Romans, the Hollywood stars at the Excelsior could enjoy imported smoked salmon and antipasto Italian style for starters, spaghetti arrabiata with clams, golden fried brains and artichokes, or calf-liver and bacon. And for dessert, crêpes Suzette and peaches cardinal. It was a tradition for Hollywood stars to go to Alfredo’s for his famous fettucine and for the guest of honour to be presented with a gold fork and spoon, or to try Sicilian cassata at Café El Greco.

The New York Times in 1950 advised American tourists not to follow the guidebook or hotel concierge recommendations as they are ‘liable to recommend establishment with about as much Italian food and Roman atmosphere as Schrafft’s’. Instead they recommended the Taverna Margutta, on enchanting Via Margutta, where ‘there are always people sitting there twirling spaghetti on their forks and enjoying a bottle of Chianti,’ or a coffee shop ‘where young people stand around the counter, talking, gesticulating, flirting and sipping thick caffe espresso’.

One of Hollywood’s top gossip columnists, the indomitable Hedda Hopper, said she fell in love with Rome during the war, despite the hardships, and she made sure she planted herself at the Excelsior Hotel whenever she was in Rome, where she could wire back to the States the latest gossip.

Gladys Lloyd, wife of actor Edward G. Robinson, wrote to Hedda Hopper on 29 June 1949 that Rome ‘is swarming with our “own“,’ and that she was staying on the same floor of the Excelsior with Joan Perry, wife of Columbia Pictures boss Harry Cohn:

Elia Kazan and Arthur Miller have been at several wonderful dinners given by producers Liper and De Sica who made Shoe Shine and a new heartbreaker I have just seen called The Bicycle Thief. Wow! What a town … The cafés and outdoor nightlife generally are just what makes the weary ones gay and you sleep beneath warm blankets every night.

A large cocktail party at the Casina Valadier on the Pincio hill was given in honour of Lloyd and Robinson’s arrival in Rome. The actor was hired to judge an Italian beauty contest, Miss Cinema 1949, at open-air nightclub La Lucciola in Villa Borghese. He told the cheering crowd, in Italian, ‘having me here tonight instead of a Clark Gable is like asking for caviar and receiving baked beans.’

He thanked Hedda for her support over ‘the malicious damage’ that could be done to a reputation.

Another reason for the embracing of Rome for many figures in Hollywood was the communist witch-hunt in America at that time. Edward G. Robinson had been a victim of rumour after making an appearance before the Un-American Activities Committee. He thanked Hedda for her support over ‘the malicious damage’ that could be done to a reputation. However, he knew fine well that it was Hedda who could make or break a career, and was particularly vicious to those she suspected of communist leanings.

September Affair, starring Joan Fontaine and Joseph Cotten, was the first Hollywood production to be filmed entirely in Italy, with locations shot in Rome, Venice, Florence and Capri. Joan Fontaine was given two first-class air tickets with her choice of who she could bring with her. She chose Hedda Hopper, a good friend in Hollywood. That is until they arrived in Naples and met Life photographer Slim Aarons. He had been hired to do the still photography for the film and had agreed to photograph Joan and Hedda’s arrival at the airport.

As their plane made the approach to Rome, Joan told Hedda, ‘Do you realise we’re nearing the scene of the crimes – Ingrid Bergman and Rossellini, Linda and Ty Power, Merle Oberon and Count Cini? … and you, you lucky stiff, will probably be the first one to get an interview with Ingrid.’ Ingrid Bergman, saint of the cinema screen, was about to be involved in one of the biggest celebrity scandals the world had seen, and Hedda would make sure she was first with the news …

Slim worked as a military photographer during the Second World War, eager to place himself in the action. He followed the invasion of Anzio, Italy, without the proper accreditation, taking control of a jeep to get there. He suffered a head injury when a bomb landed by the press corps, was awarded a Purple Heart for bravery, and was honourably discharged. After the war, he vowed to make the most of his life. ‘What the hell did we fight in the war for if it wasn’t to make the world a better place to live in and even occasionally enjoy,’ he told a friend, Frank Zachary. ‘From now on I’m going to walk on the sunny side of the street. I’m going to have fun photographing attractive people doing attractive things in attractive places, and maybe take some attractive photographs as well.’ Life magazine opened a bureau in Rome as the city made its recovery, and Slim took up a job there in 1948. At the Hotel Excelsior he stayed in room 648, his balcony looking onto Via Veneto, and which cost $150 a month. ‘The best part was that you could fill a girl’s room with flowers for a hundred lire, fifty cents in those days,’ he said. He lived the high life for cheap – he ordering Brioni suits, drank fine wine, and mingled with café society on the Via Veneto. Arons photographed the wedding party of Tyrone Power and Linda Christian, and snapped the happy couple at the Trevi Fountain. As well as the movie stars, his beat involved the gangsters in Italy and the Vatican, and was memorably invited to photograph Lucky Luciano on a visit to Sicily, who had been a neighbour at the Hotel Excelsior.

Joan was instantly attracted to the handsome photographer, and the two drove off together in his convertible, leaving Hedda with September Affair’s producer Hal Wallis to go to the Excelsior together. Hedda, who expected to be treated with complete respect, was furious. ‘I’ve never seen such rage,’ said Wallis. ‘I did everything in my power to appease her, giving her a larger suite at the hotel, besieging her with champagne and flowers, but she refused to melt until Joan apologised.’ Joan disappeared for two days with Slim, and when she returned, Hal pressured her to apologise to Hedda, ‘who threatened to fly back to Hollywood and destroy our picture in print. Joan finally did so, and a truce was called.’

Fontaine moved into Slim’s suite at the Excelsior and she was glowing with happiness as he took her on sightseeing trips in his convertible, or moonlight carriage rides. However Joan had a habit of disappearing from set with Slim without letting anyone know where she had gone, particularly tricky when it was just herself and Joe Cotten who were in most of the scenes together.

Thirty-seven-year-old Tennessee Williams, the American playwright, first arrived in Rome in late January 1948, having shot from obscurity to adoration and critical acclaim following the success of his plays The Glass Menagerie and A Streetcar Named Desire. Riding on the wave of his sudden success, he left New York for Europe. His first stop was Paris, but the city turned out to be disappointing to him but for ‘the quality of the whores’. However, when he arrived in Rome to work on an Italian version of Streetcar, the Eternal City captured his heart immediately – the imperial domes, spires and obelisks pushing up through the cityscape. He took advantage of a strong American dollar and low prices, and where ‘an Americano could get away with a whole lot’.

Tennessee immediately placed himself in the glamorous heart of the city, taking a penthouse room at the Ambasciatori Palace for the first couple of nights, before finding a furnished apartment on Via Aurora, just off the Via Veneto. It was a ‘tawny old high-ceilinged building’, only a block from Villa Borghese. His apartment had two rooms – a comfortable living room with huge windows looking out onto the sun-drenched street and old walls of Rome. The bedroom, with its heavy shutters, was almost taken up entirely by a huge double bed.

He found that as a gay man he had some freedom that he couldn’t find at home, as he believed the Italians were ‘raised without any of our puritanical reserves about sex’. Many evenings would be spent cruising on the Appian Way, where he could park up his car beside the old tombs, listening to the sound of crickets in the air, and then ‘a figure appears among them which is not a ghost but a Roman boy in the flesh!’ Before he made his name as a playwright, Tennessee cruised Times Square with another young writer, picking up GIs and sailors, soliciting them to come back to their Village apartment. He observed in Rome that prostitution was evident on the streets and in the cafés of the Via Veneto, and where secluded corners of the Villa Borghese offered shelter for illicit trysts for lonely foreigners. ‘I was late coming out, and when I did it was with one hell of a bang,’ Tennessee wrote in his memoirs.