Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

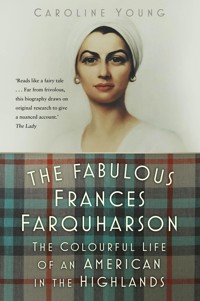

'Reads like a fairy tale … Far from frivolous, this biography draws on original research to give a nuanced account.' – The Lady 'Immerse yourself in The Fabulous Frances Farquharson … an American who brought glamour and vision to the pages of this magazine, and later – as the wife of a laird – to the remote Highlands of Scotland.' – Harper's Bazaar From society belle in turn-of-the-century Seattle to editor of Harper's Bazaar and lady of a vast Scottish Highland estate that borders Balmoral Castle, Frances Farquharson was a charming, one-of-a-kind and sartorially flamboyant woman. Born in 1902, Frances Lovell Oldham left the Pacific Northwest in her early twenties to pursue a journalism career in Europe. She transcended boundaries as a working woman in London, where she mixed with royalty, partied with the Bright Young Things and forged a close friendship with Elsa Schiaparelli. Her story is even more remarkable given she made a career comeback after fracturing her spine during a house fire that killed her first husband in 1933. At Harper's Bazaar, she would raise the morale of British women during the Second World War, and embarked on a fearlesss trade mission to the United States to boost British exports. After marrying Captain Alwyne Farquharson, the 16th Laird of Invercauld, in 1949, Frances threw herself into life as the queen's neighbour at Balmoral and brought glamour and eccentricity to the grouse moors of Deeside. Caroline Young's colourful biography offers a glimpse into the life of this remarkable woman and will not fail to fascinate and enthral.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 431

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Front cover illustration: A 1930s illustration of Frances.

First published 2023

This paperback edition first published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Caroline Young, 2023, 2024

The right of Caroline Young to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 254 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Part One: Miss Frances Oldham

Part Two: The Hon. Mrs James Rodney

Part Three: Mrs Frances Farquharson

Notes

Bibliography

Foreword

Some years after my mother’s death, when going through her papers, I found a considerable amount of handwritten and undated chapters in her unique handwriting. It was the beginning of a book which she obviously never wrote.

A great deal of what she had written about was her life in Seattle and the beginning of her travels in Europe, which was new to me and I found it incredibly fascinating. It was groundbreaking, especially for the early 1900s, and I felt it would be nice to share her life story with you.

She really lived four completely different lives, beginning in Seattle via Europe and England, and culminating in the wilds of Northern Scotland.

Shorty afterwards I was approached by Caroline Young, who asked permission to write about my mother. She sent me her book about Coco Chanel and having read it I decided to let her take on the task. Together we have pieced together her life like a jigsaw puzzle – much enjoyable! I hope you will enjoy it. I am very grateful to Caroline for all her work.

There is no doubt my mother was a truly remarkable person and I feel very fortunate to have had her as my mother. She is much missed.

Marybelle Drummond

Acknowledgements

Firstly, thank you Marybelle for allowing me to tell the story of your mother, and for providing her partially written memoir, which helped me piece it all together. I’m eternally grateful! Over the last couple of years, I’ve loved exploring Frances’ colourful life and I only hope that I have done her justice. Hearing Marybelle describe her mother so vividly, insisting that there was absolutely no one like her – she was so incredibly unique, flamboyant and charming – stayed with me as I worked to complete this biography. Marybelle also put me in touch with her second cousin in Seattle, Heidi Narte, who shared photos of Frances and her father, and provided some of her knowledge and research into her early life in Washington.

I also owe gratitude to Georgina Ripley, curator of modern and contemporary design at the National Museum of Scotland, who first told me about the American in the Highlands and her fabulous wardrobe. I was researching my 2017 book Tartan and Tweed and Georgina mentioned that Frances Farquharson was a wonderful example of someone who put her own stamp on tartan, combining the traditions of the fabric with an eccentric flair. It was at that moment I made a mental note to find out more about Frances, and it was during the Covid pandemic, as I explored new writing opportunities, that I was able to begin delving into her life.

Thanks also to Lisa Mason, assistant curator of modern and contemporary design at the National Museum of Scotland, who shared photos and details of the museum’s collection of pieces from Frances’ wardrobe, and who showed me the Schiaparelli dresses and suits, and a natty rainbow-coloured bag and matching peep-toe shoes from Saks Fifth Avenue.

As part of this research, I visited the collection centre at Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museum and viewing the items in its collection, including the famous tartan cape, tweed suits and colourful evening gowns, gave me further insight into her fabulous wardrobe. Thanks to Morna Annandale, Madeline Ward and Jenna Rose at the galleries, who arranged this and were helpful with my questions.

I’m really grateful to Norma Sudworth, who spoke so wonderfully about her father Norman Meldrum, who was Captain Farquharson’s personal piper. And to David Geddes, president of the Braemar Royal Highland Centre, and Doreen Wood, who sat down with me in the visitor centre to discuss their memories of Frances. Doreen opened up the doors of Braemar Castle for me so that I could take a look around and explore. It was the day before it was set to close for an extended refurbishment, so it felt very fortuitous.

Charlotte and Catherine Drummond, thank you for sharing your memories of assisting Frances at Invercauld, and of her kindness and wisdom; and to Hugh Cantlie for granting me some time to talk about how Frances was such an encouraging force of nature. I’m also grateful to Marcia Brocklebank, who spoke of her friend Francie so beautifully, describing her colour, dynamism, warmth and kindness.

Thanks to Justine Picardie, who kindly shared her knowledge of being a Harper’s Bazaar editor, as well as some of her discoveries when she had looked into Frances’ life.

I’m also very grateful to Annie Stewart of the Scottish textile company Anta. We met for coffee in Edinburgh, and her impressions of Frances from that time were invaluable. She kindly gave permission to use her beautiful Anta Frances Farquharson tartan on the cover of this book, which she was inspired to design after meeting her in 1990. The beauty of this fabric is a perfect representation of Frances Farquharson and her distinctive and impressively inimitable life.

Finally, thanks to my agent Isabel Atherton at Creative Authors, and Mark Beynon and Rebecca Newton at The History Press for their encouragement and support.

Introduction

On the outskirts of Aberdeen, in a purpose-built modern construction, is the archive of the Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museum, a temperature-controlled storage space with rows that unfold like butterflies to reveal countless treasures. Within this vast collection is the extensive, perfectly preserved wardrobe of Frances Farquharson.

As the beautiful American-born editor of the British edition of Harper’s Bazaar in the thirties and forties, you’d expect that Mrs Farquharson would possess the fabulous wardrobe to match. There are hundreds of items in the archive, from delicate silk dresses and blouses by Schiaparelli and Mainbocher to sturdy but smooth-to-the-touch tweeds from local weavers, polished leather shoes and gleaming brooches, and the bright powder-puff tam-o’-shanters that were her signature in the Highlands of Scotland. Indeed, this collection not only reveals the rich and varied life of a fashion dynamo but also provides an insight into what made her so attractive to all who knew her.

She was the vivacious American who charmed aristocracy when she arrived in Europe from Seattle in the roaring twenties. Glowing with enthusiasm, she was an energetic counterpoint to Old-World tradition, and whenever she arrived in a room, all eyes were drawn to her. As a fashion journalist in the thirties, she lived a whirl of exclusive parties, fashion shows and debutante balls, where she introduced Elsa Schiaparelli’s daughter at the 1938 season. Her patrician image regularly featured in the society columns, a regal sculpted eyebrow, sharp cheekbones and a halo of fur accentuating her dark-haired beauty.

Alongside the black wool dress by Edward Molyneaux and the cream blouse by Elsa Schiaparelli, both of whom were personal friends, there are vintage pieces from Marks & Spencer, including a black pleated day dress from the 1940s, which wouldn’t look out of place in department stores today.

She wasn’t particular about labels – if an item was well made and flattering, she would embrace it. Evening mules decorated with hearts were worn to a New York Valentine’s Day ball; there’s a summer dress bought on a trip to Palm Beach in 1930; yellow espadrilles from Majorca; a tartan two-piece swimsuit to champion Scotland when on beach holidays in the 1950s; a printed Hermès silk turban from the 1940s; pairs of glitzy peep-toed Delman shoes; and a selection of mohair skirts and tops from Scottish manufacturers in an array of brilliant hues.

Also included in the collection is a pair of brown shoes which were part of the government’s utility scheme, introduced in 1942. Following the outbreak of war in 1939, Frances earned plaudits for her wartime leadership of British Harper’s Bazaar, under her business name, The Hon. Mrs James Rodney, from her late first husband. Not only did she print morale-boosting messages and practical advice to the women of Britain, who were suffering under bombing raids and rationing, but she delivered an ambitious campaign in the United States to encourage American department stores to buy British. As the only woman in the boardroom, she actively persuaded the Ministry of Trade and reluctant textile manufacturers, who were sceptical of her feminine energy, that British exports could deliver much-needed dollars to help win the war.

A red leather Elsa Schiaparelli travel bag still has a brown cardboard transport tag attached to it, handwritten with the words ‘Invercauld’. The bag may have been from the 1930s, but Frances was carrying it with her more than a decade later, when she first visited Royal Deeside with her third husband, Captain Alwyne Farquharson, the 16th Laird of Invercauld. After the war, she spent the second half of her life in Invercauld, in the heart of the Cairngorms on Royal Deeside.

The item in the collection that sums up Frances the most is the dramatic Farquharson tartan wool cloak, worn with a matching jacket, skirt and cap, which was custom-made for her by Aberdeen tailors Christie & Gregor. It was once she married Alwyne, Chief of Clan Farquharson, in 1949, that she fully embraced Scottish traditions to affirm her new position as lady of one of the largest estates in Scotland and owner of two castles – Invercauld and Braemar, and Torloisk House on the Isle of Mull. She wholeheartedly embraced the Highlands, where she was tireless in promoting the culture – its history, music, cottage-industry arts and its textiles.

With her flamboyant glamour and the tartan capes punctuating every sweeping gesture, she became one of the most recognisable figures in the village of Braemar, and her indomitable and persuasive persona helped to bring much-needed business to the area. For almost fifty years she appeared side-by-side with the royal family in their pavilion at the annual Braemar Gathering, where she ensured she was always cheerleading Scotland, and its textiles, in her eye-catching tartan outfits.

If you wish to follow in her footsteps, Braemar is an hour’s drive from Aberdeen. The further west you travel, the road becomes windier and the gentle green farmland turns craggy and rough, with endless hills covered in smatterings of gorse and heather. The grouse moors resemble a piece of tweed fabric, in their rusty browns, oranges and greens, like the leaves that blaze in autumn. Eventually, you come to the immense Invercauld Estate, which edges onto the deep forests of Deeside. Invercauld is only a short drive to Balmoral Castle, reached along a narrow road which clings to the River Dee and is flanked by deep forests of soaring pine trees.

In the village, there are faint whispers in the air, and in the babble of the Cluny Waters that cuts through it, of a remarkable woman and her unique spirit. Her influence is evident in the yellow and pink interiors of the turreted fairy-tale castle, Braemar. In the disused local church, where she ran a theatre, she designed pink murals which told the story of the Farquharson family, but these have long been hidden away when the building was converted to flats. The fashion boutique, men’s sporting clothes shop and the antique shop she founded in the village closed soon after her death, and the colourful embellishments to the grey granite of Invercauld, such as the yellow window frames and pink game larder, have been painted over.

Still, you can imagine her draped in the green and blue Farquharson tartan, resplendent against the grey stone of Invercauld Castle, and with the outdoor larder like a rose petal against a layer of fresh snow. As her daughter Marybelle Drummond said, ‘Like most Americans, she didn’t do things by halves. She didn’t paint, but she was an artist, expressing herself through clothes and colour.’

I first came across one of her elaborate tartan costumes in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, which also holds an extensive collection of pieces from her wardrobe, while researching a book on tartan, and the story of a true fashion original living in Scotland captivated me. I made enquiries at the offices of Invercauld as to whether I could be put in touch with her family, so that I could delve a little deeper into her life. Her much younger husband, Captain Alwyne Farquharson, who had celebrated his centenary year in 2019, had been namechecked in an episode of Netflix’s The Crown in Season One, for leasing some of his moors to the queen. A couple of weeks later, I received a phone call from Marybelle and a handwritten letter from Captain Alwyne, from the Farquharson seat in Norfolk, where the captain now lived with his second wife:

I should begin by telling you I am now aged 101 years old, exceptionally deaf, and don’t see as well as I once did, but I will try to help you as best I can. My darling wife Francie was indeed remarkable in many ways, and enjoyed helping people develop their talents.

Over the course of several more phone calls with Marybelle, we chatted about Frances’ life and how best to tell her story in a biography. As I learnt more about her, the more intriguing she became. She possessed a completely unique and intuitive sense of style, a natural warmth and charm that drew people to her, and a contagious joie de vivre. She was larger than life; a force of nature who threw herself into every new adventure with gusto and held a lifelong passion for helping others achieve their best. All those who received a letter from her could attest to her distinctive and effervescent looped handwriting in black marker. As a journalist, she had an impeccable memory, never taking notes and never forgetting the details about the people she interviewed.

She came of age at the dawn of a new era for women’s liberation, yet it was still incredibly unusual for an American woman to live her life so independently. She chose to travel the world, rather than settle down to raise a family in her hometown. She crossed the Atlantic with her eyes wide open, relishing each new experience, and in turn, Old Europe was receptive to charming American girls like her, who were beyond the restrictions of the established class system.

The upper echelons tended to be off limits to those who hadn’t been born into it, but Frances was welcomed into the most exclusive spaces, from London’s Marlborough House to a Romanian royal palace in the Carpathian Mountains. She used her own talents and magnetism to forge a path into the top rungs of society, where she met some of the most interesting figures of the day and was witness to some of the major events of the twentieth century.

Her life may have resembled that of an American character in a Henry James novel, who is both intrigued by and intriguing to Europeans. Perhaps she could be considered a real-life Isabel Archer from The Portrait of a Lady, a New-World beauty who moves to Europe to stay with her aunt, mixes with old money and is determined to see all she can and maintain her freedom, before choosing a husband and settling down. At a time when women rarely found independent success, Frances transcended boundaries as a working woman of her own means, and unlike Isabel Archer, she wasn’t constrained by her husband when she did decide to settle.

I discovered that she’d gone by several different names throughout her life, with each one defining the next chapter in her journey. She was Frances Lovell Oldham, the Hon. Mrs James Rodney, Mrs Charles Gordon, Mrs Frances Farquharson of Invercauld. She was a Seattle Gibson Girl in the first decades of the twentieth century, a jazz-loving American in Europe in the twenties, a fashion editor for one of the most influential magazines in the thirties, and a rallying force during the Second World War to make a difference to the war effort. By the fifties, she used her persuasiveness and influence to boost the fortunes of Invercauld Estate and to help put the tiny village of Braemar on the map. Throughout her life, she created different worlds for herself, as if they were distinct chapters in her book, moving on to another incarnation when one was closed.

Many aspects of her life could be defined by that eye-catching tartan ensemble on display in the fashion galleries of the National Museum of Scotland. Among the eighteenth-century panniers, corseted Victorian gowns and sixties mini-dresses is a feast of tartan extravagance: a Turkish harem trouser suit and turban in vivid green-and-blue checks, cut with narrow stripes of red and yellow. It’s a rare and kitsch combination of Scottish heritage and Middle Eastern style, and it was the type of suit that could be mistaken for a punky Vivienne Westwood or Jean Paul Gaultier. But rather than being created and worn by an enfant terrible of the seventies and eighties or shipped to the Highlands by a Paris atelier, it was of course conjured up by Frances herself.

As well as showcasing her family tartan, the suit represented her career as a prominent fashion editor, and her fascination with other cultures. After sketching it out, she gave her design to a local tailor, who constructed it from silk fabric in the Farquharson tartan. I found out, through conversations with Marybelle, that her mother wore it to one of the famous ghillies balls at Balmoral Castle in the late fifties, hosted by Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip. Held every September to mark the end of the summer season at Balmoral, the dance was a tradition begun by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in their first year in the castle in 1852, as a way of thanking their staff and servants.

As the sun set over the turrets of Balmoral Castle, the guests waited to be greeted by the Queen and Prince Philip in the drawing room. It was a custom of the ball for ladies to wear long ballgowns, and for gentlemen to be in black-tie Highland dress, with a kilt in their family tartan. But here was Frances, dressed in tartan by way of the Middle East, and wowing the room with her warm, magnetic personality. As the guests took to the ballroom floor to dance the Eightsome Reel, we can only imagine the comment Prince Philip would have made about such a striking outfit.

The eccentricity of this outfit perfectly encapsulated her sense of fun, her confidence and her innate affection for Scotland. Hers is a remarkable story, and through the eyes of the Fabulous Frances Farquharson, we can experience the life of a very modern twentieth-century woman.

9 December 1933, Hampshire

The fire broke out in the early hours of an icy December morning, when the crackling of flames cut through the stillness of the night and the corridors of the country home choked with acrid smoke. Frances and James Rodney had only retired to bed a few hours before, having spent an evening being entertained by their host, famed Chicago architect Leander J. McCormick, and his wife, Renée, the Countess de Fleurieu, in the comforts of their antique-filled drawing room, warmed by a roaring fire.

They were awakened by the sound of Mrs McCormick’s panicked French lilt calling out in the night to rouse her sleeping guests and servants. Mid-slumber confusion was followed by the realisation that the house was on fire. They pulled back the covers of the four-poster bed and rushed out the bedroom door into the hallway. With smoke clouding their view, they felt their way to the staircase, but just as they reached their escape route, flames shot out over it, engulfing the main exit point in the house. Frances and her husband of five years, Captain James Rodney, had been invited for a weekend retreat at McCormick’s newly renovated historic country spread, known as the Heronry. McCormick, originally from Chicago, was the son of the author and inventor L. Hamilton McCormick, and grandson of one of the founders of the International Harvester Company. He may have been of rich American stock, but he was raised and educated in England, having attended Eton and Cambridge. He had recently wed the Countess de Fleurieu, herself an author of several novels set in France, including Dangerous Apple, and had adopted her two children from her first marriage. With his architect’s eye, having worked on some of Chicago’s most prestigious buildings as part of a wave of modernist construction in the first decades of the century, he used his trust fund to purchase an idyllic English country manor in need of renovations.

The Heronry, an old mill house with an irregular shape from the adaptations and extensions carried out over the years, was 2 miles from the picturesque Hampshire village of Whitchurch, and positioned by the River Test, which was renowned for its trout fishing. After moving in the year before, the McCormicks spent £3,000 modernising it, with electricity powered by the mill in the river and central heating installed to take the edge off the cold and bring it into line with an American’s expectation of comfort. Renée had decorated it in the French style, with crisp white walls, heavy curtains and antiques to complement the oak panelling. Leander had recently received a shipment of some of his paintings from his home in the United States, which he hung proudly on the walls of his retreat.

Typically, after breakfast, McCormick would go down to the bottom of his garden to fish for fat trout and would encourage his guests to do the same. On news of the fire, a society columnist at the Daily Mail recounted how they, too, had stayed at the Heronry just a few months before, in a room close to where the Rodneys had been sleeping:

That week-end I had caught a large basket of trout in a neighbour’s stream, and coming in late for dinner had told my hostess that I had brought the basket into the hall. She cried out in mock alarm, in her delightful broken English. ‘Why you bring those nasty fish inside my lovely white house?’1

To celebrate the remodelling of the home and bring in the Christmas season, the McCormicks hosted a weekend for a select group of guests, including Frances and husband James, who had visited previously. As a writer for several publications, including Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and the Daily Mail, Frances’ authoritative voice offered insights into the sailing season on the Isle of Wight, the best country retreats to visit for the weekend and advice on finding harmony in marriage. She spoke from first-hand experience; her marriage to James was considered one of the most loving in London’s top circles. They adored one another, both respecting each other’s needs, and with James fully supportive of her career as a writer.

James, the son of Lady Corisande Evelyn Vere Guest and the late George Rodney, the 7th Baron Rodney, was tall and chiselled and sported a dashing moustache that made him look every inch the flying hero of the First World War. He was now working as an insurance broker for his uncle, Ivor Guest’s firm, while also fuelling his love of aviation as the trainer for Britain’s first auxiliary flying squadron. They’d married in 1928, settling into a life of domestic bliss in their cosy house in Marylebone, which she’d painted in bold yellows, reds and purples and decorated with treasures gleaned on her extensive travels.

In one of her regular Seattle Daily Times columns, which recounted her trips around Europe, Frances spoke of the effects of being an American overseas and she was ‘always seeking in every face a familiar one from home’. McCormick was one of these familiar faces, not only through the recognition of his accent, but his way of conducting business; the Americans just had a different way about them.

Another guest at the weekend party was Louis Jean Marie, the 12th Duke de la Trémoille, the 23-year-old heir to one of France’s oldest families. Having succeeded to the title at the age of 11, following the death of his father, he was the last male of his direct line, as the title couldn’t be passed down via his four sisters, who had all married into branches of European nobility. The duke had completed his military service in the French crack cavalry regiment, Chasseurs d’Afrique, and was looking forward to some relaxation in the English countryside. He arrived at Croydon Airfield from Paris on the Friday afternoon and was driven to meet his hosts at the Heronry.2

Following dinner at 8 p.m., the McCormicks and their guests had spent a quiet evening by the fireside, with the duke entertaining them with his array of card tricks. They retired to bed just after 11 p.m., drifting into hazy sleep. What started out as a small fire in an unoccupied bedroom soon spread out across the carpets, licking its way up the wood panelling and around the door frames.3

After rushing to wake her husband, Renée McCormick ran through the corridors in her nightgown, shouting warnings to their guests and servants. With the smoke thick in the air, they felt their way along the halls to the duke’s room, and Renée called out to him, instructing him to find his way to the stairs. To their relief, they heard him shout out a reply that he was making his way out. With no time to grab an overcoat over her nightwear, and trapped on the first floor, Renée climbed out of the window, lowered herself down and ran across the lawn to the garage, where the chauffeur, Frank Jackson, and his wife, slept in a room above. He immediately rang the fire brigade at Andover, which was 6 miles away.4

The servants of the house gathered outside, still in their nightclothes, desperately trying to do what they could by throwing buckets of water on the flames and searching for ladders to reach the upper windows. The heat from the blaze radiated into the ice-cold atmosphere, and smoke billowed from the windows and into the air.

Unable to find the staircase through the smoke, Frances and James retreated into the bedroom, closing the door tightly behind them, in the hope that they could escape through the window. But there was no ladder available and it was a 20ft drop to the ground. James was recipient of the Distinguished Service Order, the Star of 1915 and the Military Cross for his service in the war, which was cut short when he was wounded in action in France. These experiences may have helped him keep a cool head with the awful realisation that the only way out was through the window.5 Frances looked down at the ground below and recoiled at the thought of jumping so far to the ground.

The flames were crackling outside the door, and smoke crept underneath the gap. Soon it would infiltrate the room, making it impossible to breathe.

James gathered up sheets and towels to make a rope they could climb down, and he smashed the windowpane with his fists. He helped Frances clamber out of the window and on to the narrow sill, holding onto the rope. She lowered herself down, aiming for the flower beds directly below in the hopes it would cushion the fall. She slipped, landed awkwardly, with a thud, and cried out as the pain radiated through her back. Seeing her distress, James jumped after her onto the flower beds and rushed to Frances, who was struggling to move. The Seattle Times later described Captain Rodney’s heroism; even though he was suffering cuts and burns, he thought only of his wife.

When the ambulance arrived from Andover, the Rodneys were taken to Royal Hants Hospital at Winchester and Frank Jackson organised a roll-call of the guests and servants. An older German maid, Louisa Krug, had similarly been trapped in her room but had managed to escape by clambering down the drainpipe. As Jackson called out the names, it became apparent that the Duke de La Trémoille was missing. After Leander tried throwing pebbles at the duke’s bedroom window, Jackson got hold of a ladder and climbed up it to take a closer look. He broke the glass in the window to see better, but through the smoke there was no sign of him.

Renée was adamant that she had heard the duke calling out that he was heading for the staircase, and in the confusion, no one had noticed that he wasn’t outside. It was only once the fire was extinguished after dawn that the charred body of the duke was discovered in the ash. It was later thought that he had become disorientated in a house he was unfamiliar with and found himself trapped in the upstairs bathroom when he had seen the stairs alight.

The fire was so severe that the floor caved in, sending him plummeting into the pantry on the ground floor, and he was engulfed in flames. Frances would later recount a story she’d heard that there had been a curse placed on his ancient family, where the eldest son was destined to die by fire.

At the hospital, Frances was taken for an X-ray, which revealed that she had fractured a vertebrae in her spine. She underwent an operation to repair some of the damage, and the hospital released a bulletin that she was ‘seriously ill, but there is no reason why she should not pull through’.

Before being taken into surgery, Frances insisted to her nurses that her husband should be kept informed of her condition. She hadn’t seen him since their ride in the ambulance, and she was concerned that he would be fretting at not knowing how she was doing. No one had the heart at this point to tell her that, despite having seemed fine, her beloved husband had died soon after his arrival at hospital.

Summer 1985, Invercauld

Except for the splash of yellow on the window frames and the pink of the outdoor games larder, popping like cherry blossom, the solid granite towers and gables of Invercauld were a sober presence in the Dee Valley, set against a stirring backdrop of mountains and pine forest and with the rush of the river Dee flowing through. The sixteenth-century castle had been extended and reinvented in the last century as a romantic Highland confection in the Scots Baronial style, and over the last decades, had been brightened by the colourful touches introduced by the chatelaine, Frances Farquharson. Sometimes described as ‘eccentric’ in her wearing of tartan, head to foot, she laughed it off and declared herself ‘more Scottish than the Scots’. As her husband, Alwyne, who was seventeen years younger, dryly stated, ‘If my wife’s eccentric then I must be eccentric’.6

Inside the fourteen-bedroom mansion, with its maze of staircases and passageways, Frances was sitting on her tartan sofa in one of the most relaxing rooms in the house, with the veteran British journalist Joy Billington, who was writing for the Washington Post. On Joy’s arrival, Frances, dressed in a tartan skirt and Shetland wool sweater, greeted her warmly. She led the reporter up the mighty stairwell lined with portraits of the family’s Farquharson ancestors and along the warren of passageways to show her into the Tartan Room, which offered a more intimate space for entertaining her guests. For one thing, it was often the warmest room in the house.

The light streamed through the window as she offered tea and shortbread, served on delicate china, to the ash-blonde reporter, and Frances gave no sign that her back was aching. It had been fifty years since she’d fractured her spine in the terrible fire. She was now 82 years old, still sprightly and with enthusiasm sparkling in her eyes, but increasingly, she’d been struggling with her health, not just with her mobility, but with kidney issues and rheumatism. Yet she was always stoical, never complaining, and typically chose not to reveal much about her past, rarely talking about the night of the fire or the years spent in recovery.

She preferred to concentrate on the present, rather than events in previous incarnations, as that was when she was the Hon. Mrs James Rodney, and she was now Mrs Frances Farquharson, and had been for four decades.

She had fully embraced Highland living after marrying the laird in 1949, and in the years since, she had become entwined with the land. Arriving in Braemar like a cannonball of energy, she had immediately injected vitality into the sleepy village which, like Brigadoon, only seemed to come alive once a year for the Braemar Gathering. She fought to boost its fortunes by bringing culture and business to the region and did all she could to keep Invercauld Estate afloat, as there were hundreds of people whose livelihood depended on it. ‘It’s just as well you didn’t marry a dolly bird,’ she told her husband, ‘as the estate would never have survived.’7

Joy Billington had moved to Scotland with her chaplain husband, and as part of her fondness for interviewing women of renown, she had approached Frances to talk about her life as the lady of a vast Highland estate. She was interested in the reasons why she had opened her home to paying guests, particularly very rich American ones, and she was also curious about her life before, one Billington described as ‘pure Henry James’ – leaving her Seattle home at a young age and being initiated into European society with help from ‘two aristocratic Russian godmothers in Paris and London’.

‘There are quite a number of reasons,’ Frances told her, as she answered the first question:

One is tax. Our taxes here on the land are crippling and if you do a certain amount of open house, you get certain concessions on maintenance. And of course, maintenance in this part of the world is a very costly thing. Your rooms, your doon spoots, everything to do with the maintenance of a big property.

Joy was momentarily confused by the expression, ‘doon spoots’.

‘That’s down spouts?’

Frances nodded. She spoke rapidly, as she recounted the fabulous dinners and entertainments that attracted paying guests and the week-long shooting parties, even though she was averse to killing anything herself. They would draw in incredibly wealthy Americans – the Rockefellers, the du Ponts, international celebrities like Eva Gabor and a group of Swedes who were relaxed about which husband and wife slept in the same bed with whom. Invercauld came alive during these events, where the bejewelled guests were led into a candlelit dining hall by the piper, who also served as plumber during the day, and where the table was set with beautiful silver and vases of flowers.

As she took in her surroundings, with views over the tree-covered valley to the river, Joy couldn’t help but comment on all the tartan furnishings, from the settees to the tables to the screens. ‘You obviously love tartan,’ she said.

‘Well, it’s called the Tartan Room,’ Frances wryly replied.

‘Could you have ever guessed as a girl in Seattle that you’d own 300,000 acres?’ Joy asked, as she tried to find out more about her life before.

‘I don’t feel I own it even now,’ Frances replied. ‘I feel I belong to it. As I belong to the laird, my husband.’

This remote Scottish estate was thousands of miles from the American city where she was born and was almost a world apart. As colourful as her life had been, it was an extraordinary leap for a girl from the Pacific Northwest to now be the caretaker of spectacular heather- covered hills, grouse moors and a 24-mile stretch of the River Dee, crystal clear and teaming with salmon. No doubt the fast-growing city of her youth would be barely recognisable to her, yet the Highland landscape must have reminded her of the vast mountains and lakes of Washington. Because it was in turn-of-the-century Seattle that Frances’ remarkable story begins.

Part One

Miss Frances Oldham

Chapter One

‘Although I was born in Seattle, I always felt, from the very beginning, that I was destined to live my life on the other side of the Atlantic,’ Frances reflected in the draft pages of an unpublished memoir, written later in life. ‘I was American born, of American parents, but for some odd reason I never felt that the United States was my real home.’

As a child she was enveloped in the beauty of America’s Pacific Northwest, where the clouds clung to forest-clad mountains and lingered over Puget Sound. Spending the second half of her life in the Scottish Highlands, it was as if she’d nurtured a lifelong spiritual connection to an awe-inspiring, rugged landscape. Yet growing up among such expansive beauty, she felt a deep desire to see beyond sleepy Seattle and Lake Washington to the vibrant capitals of Europe. Her father had, as he told his daughter, travelled west ‘to get away’ from his relations, and later, she was desperate to rediscover them. ‘My father loved the West and succeeded in transferring his love of the wild open spaces to my younger brother and sister, but I was his black swan,’ she recalled. ‘I dreamed of the capitals of Europe at night, and it never even occurred to me that I might never see them.’

Her father, Robert Pollard Oldham, was just out of Harvard University law school when he arrived in Seattle at the turn of the century. Following his graduation, his father, a renowned Ohioan judge, Francis Fox Oldham (who went to the Treasury Department in Washington, DC as legal adviser in 1903) offered to pay for a voyage around the world as a ‘final fling’ before he settled down in a law office. Robert planned out a trip that would take him the breadth of the United States to the west coast and then across the Pacific to the Far East.

Yet landing in Seattle as an idealistic 25-year-old, his travels were side-lined when he was introduced to a young beauty named Mary Bell Strickland, of a grand Bostonian family, whose ancestors were the historian Agnes Strickland and the American engineer and inventor of the steamboat, Robert Fulton. Born in Pendleton, Oregon, in 1882, and going by the name Bell, she arrived in Seattle in 1901 following schooling on the east coast.1

Robert fell in love with both the majesty of the Pacific Northwest and with dark-haired Bell, and they married on New Year’s Day, 1902. Instead of continuing with his plans for travelling, Robert opened a law office in Seattle. The city would be his home for the rest of his life. As Frances noted, ‘I obviously did not inherit my desire to travel from him.’

Frances Strickland Lovell Oldham, their first child, came into the world on 19 November 1902. She was named Frances in honour of her father’s younger sister, and her middle names referenced her mother’s maiden name and the Lovell lineage of her grandmother, Betty. Frances’ younger brother, Robert Pollard Oldham Junior, was born a year and a half later on 18 March 1904.

The family lived in comfort in a large home at 1234 Eighth Avenue West, which rested high above Elliott Bay and offered spectacular views across Puget Sound. Young Frances loved being able to play in a garden that looked out over the sparkling bay and where the scent of pine was carried on the wind.

After being introduced to horse riding from the age of 3, she was given her own pony, which she kept tied up in the back garden. She frequently practised riding on him and this skill would stand her in good stead when it came to mixing with Europe’s aristocracy when she was in her twenties.

The family home was also well placed for experiencing the Pacific Northwest’s lakes and mountains, and Frances threw herself into sports, embracing canoe paddling and fishing on the lakes in summer, and skating and skiing in winter. ‘All these sports I took in my stride as the seasons came and went,’ she said.

Despite her childhood dreams of going to Europe, her history was very much entwined in the traditions of America. Frances’ family dated back to the country’s founders. Her father was a direct descendent of Elizabeth ‘Betty’ Washington, sister of George Washington and one of the founding mothers of the United States.

‘The College of Heraldry traces George Washington’s ancestry – and consequently my own – from Charlemagne and his first wife. So, I probably inherited my feeling for Europe from my remote ancestry,’ Frances wrote in her memoirs. It was Frances’ pride in this ancestry that partly led her to Europe when she was in her early twenties, touring the royal palaces of the dying Balkan states. Once she was living in England, she actively sought out the details of her lineage, which did indeed go back to the first emperor of Europe, and then to Charles the Bald.

If there was one element that passed down the generations to Frances, it was George Washington’s love of the finer things in life, an eye for the details when it came to fashion and an appreciation of British and European style. As commander-in-chief for the Virginian forces in the French and Indian War, he ensured he looked the part by purchasing luxury clothing in London, including ruffles and silk stockings, and sketched out the uniform of his officers – blue coats with scarlet cuffs and matching waistcoats. He had never been to England, yet he tried to imitate the style of an English gentleman and furnished his Virginian plantation, Mount Vernon, with fashionable pieces shipped from London, including Wedgwood earthenware, silver-handled cutlery and a green four-horse coach, which was all the rage in London.

At the age of 17, in 1750, his sister Betty married Fielding Lewis and they had eleven children together, of which three died in infancy. Their youngest, Howell Lewis (1771–1822), travelled west with wife Ellen Pollard, building a home near Charleston, West Virginia, with enough room for their eleven children. Their oldest daughter, Betty Washington Lewis, became the second wife of English-born Joseph Lovell in 1818.

They had six children, and following Joseph Lovell’s death in 1835, Betty moved to Marietta, Ohio. Her son, Joseph Junior, married a local girl, Sarah Sophia Nye, in 1852 and they had one child, Frances’ grandmother, Betty Lovell, born in 1853. They lived for a time at the famous Meigs House, built in 1802 and named after its first resident, Postmaster General Return Jonathan Meigs Senior. It was arguably the most important home in town, and one of the most impressive in two-storeys of red brick with a grand porch looking out over the Muskingum River.

Despite being steeped in tradition, by the 1800s Marietta’s progressive politicians championed civil rights, and there were two underground railroad stops in the town, where runaway slaves could be hidden on their journey north. Over the years since its founding, the town’s historic homes on brick-paved streets were the birthplace of governors, senators and even a vice president, ensuring it made a firm mark on history. It was in this impressive little town that generations of Lewis Lovells were to live.

At the age of 23, in 1876, Betty Lovell married 28-year-old Francis Fox Oldham, a southern gentleman from Moundsville, West Virginia, who moved with his family to Marietta at the end of the Civil War. With Francis Fox now a successful circuit judge in Ohio, the Oldhams lived prosperously in a comfortable home at 1 Fourth Street. Frances’ father, Robert Pollard Oldham, was born on 19 May 1877, with his middle name chosen as a tribute to great-grandmother Ellen Pollard. Another son, Wylie Oldham, was born in 1879, but lived to only the age of 1. Despite the tragedy, his mother, Betty, gave birth to a daughter named Lovell ‘Lottie’ Oldham, on 29 June 1882 (the aunt Frances would stay with in Rome), later followed by another daughter, Frances Fielding Oldham, on 19 February 1889, with her middle name in tribute to Fielding Lewis, husband of Betty Washington, George’s sister.

Growing up in progressive, booming Marietta at the cusp of the twentieth century, it was this open-mindedness that perhaps helped instil in his daughter a sense of independence and fun, as he sought never to restrain her from taking her own path in life.

Robert followed in his father’s footsteps by studying law at the University of Cincinnati, and then enrolled at Harvard University Law School in 1898, graduating with a Bachelor of Law in 1901. After settling in Seattle, he joined the prestigious firm Bausman & Kelleher, one of the oldest in the state of Washington. By 1914, he had been promoted to partner, and earned a reputation as a major player at one of Seattle’s top civil law firms. Robert was praised in 1922 by James Boswell, author of the American Blue Book West Washington, as belonging to ‘that school of attorneys who never permit themselves to become “ruffled”, but who are, at all times, calm and dignified’.2 It was this calm, logical nature that he passed to Frances, allowing her to hold her own as a trade envoy for Britain during the Second World War, when she was the only woman in the boardroom.

Mary Bell Oldham was only 20 years old when she married and started a family, yet she settled into her life as a prominent lawyer’s wife and an active and committed member of the city’s burgeoning society. Frances, perhaps keeping this in mind when she was lady of Invercauld, remembered that her mother ‘was loved by everyone in Seattle from the chimney sweep to the wealthiest tycoon’.

At the turn of the century, Seattle was still a small town founded on an economy in logging and fishing, but it was becoming a major transport hub on the back of the gold rush, attracting several prodigious businessmen with an eye on development. By the 1910s, Downtown Seattle was lifted by a wave of new architecture, with constructions in development and architects competing to create the tallest, sleekest buildings. Robert Oldham commuted every morning to the brand-new Beaux Arts Hoge Building on 705 Second Avenue, the city’s tallest at that time, where his firm had set up offices.3

Many of the prominent Seattle families were recent arrivals from the Northeast or Midwest, and they wished to recreate the gentility and culture of the more established East-Coast cities, in a timber town which once had an untamed and rambunctious reputation. As a prominent lawyer’s wife, Bell was an important figure in town, as the ladies’ charity luncheons and tea parties were detailed in the society pages of the Seattle Daily Times. They dressed in the latest Edwardian fashions to arrive on the west coast: high-necked frilled blouses, corseted waists and long skirts, with their wide-brimmed hats resting on intricate up-dos. Their afternoon teas, where the ladies took turns to operate the tea urn, were always elaborately decorated affairs with vases of flowers and pretty china set out on white tablecloths.

Her status was also further cemented by being married to a descendent of George Washington, which was an impressive connection in a town steeped in American tradition, and where any daughters of hers would be entitled to join the prestigious Daughters of the American Revolution. Bell would also become a charter member and trustee of the Sunset Club, founded in 1912. It was one of the most important private clubs for women in Seattle, who gathered at its colonial-style clubhouse on First Hill.

Social events were regimented around the calendar. The Christmas season was filled with tea parties and dances and was, as the Seattle Times called it, ‘a strenuous winter of gaiety’. From Ash Wednesday to the lead-up to Easter was a quieter period, a time for going to church, giving to charity and restocking their wardrobes with summer clothing.4 As the summer season arrived, Seattle’s comfortable residents headed off in their motorcars to their country homes in idyllic settings on a sound, lake or island.5

While he was very successful as a lawyer, Frances’ father, known as Bob to friends and colleagues, was often focused on supporting the underdog, meaning he would sometimes give his time for free to help different causes. After arriving in Seattle, he had become actively involved in the Washington State branch of the Democratic Party. He was president of the Woodrow Wilson League, a group for independents and democrats, and later took charge of the 1924 Washington Democratic presidential nomination campaign for William Gibbs McAdoo.6

‘We always had plenty of money, but there was no feeling in my home of the importance of making more and more in order to be richer and more influential than the neighbours,’ said Frances:

My father and mother were democrats in the true sense of the word. Both had been brought up in strict Episcopalian homes in which church every day and Sunday school on Sunday was the regular routine. Father was religious, but broad-minded. He did not believe that God could only be found in the Church. He disapproved of churches in which the rich could buy the more expensive pews and the poor were kept herded in the background. He always said that he felt closer to Him in the Great Outdoors that had not been touched by man.7

While religion played a part in their upbringing, the Oldham children were not forced to go to church every Sunday and were not baptised, as Robert wanted them to make that decision for themselves. Instead of focusing solely on church teachings, their father taught them kindness, and to keep quiet rather than speak ill of people. It was a loving home, where they celebrated the American traditions, particularly with their heritage as a founding family. She treasured the Thanksgiving feasts, and always remembered ‘the delicious scent of spices and cooking which came from pantries and kitchens’.8

She had an active imagination, inventing stories to tell the younger children and spending hours in the family library. Shakespeare and Dickens were her favourite authors, and she poured over atlases and history books to trace the lines of the eastern European frontier and the famous landmarks that were waiting for her to explore – Paris, with its Eiffel Tower, Rome’s Colosseum and Pantheon and the Parthenon as a beacon over Athens.