6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Editorial Autores de Argentina

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

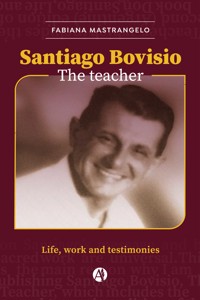

Santiago Bovisio once said: "After 2000 people will start to talk about me." In 2003, Fabiana Mastrangelo published his first biography: Don Santiago, Vida y Obra del Señor Santiago Bovisio, in Argentina and Bolivia, to mark the 100th anniversary of Bovisio's birth. The book was translated into Portuguese and published in Brazil in 2006. The book sold out in both languages and was presented in various provinces of Argentina and countries of the Americas and Europe. Numerous cultural media outlets and figures wrote about the book: "This book is a work in favour of the development of modern humanity." Beatriz Baudizzone, President of the Argentine Society of Writers, Mendoza. "The author will watch as this offspring of her spirit walks around the world, no doubt without her help because it has a strength of its own." Sara Carubin, writer. "Señor Santiago Bovisio's personality and national and international reach in the cultural and spiritual sphere clearly justifies this author's work, spreading his message." Declaration of Cultural Interest by the Deliberating Council of the City of Mendoza. "Don Santiago, with its clear and eloquent language, gives […] a universal teaching for all human beings who, on different paths, wish to live according to the spiritual ideas they long to attain." El Nuevo día newspaper, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, 29 September 2003, on the commemoration in this city of the 100th anniversary of the birth of Santiago Bovisio. "The message of the book Don Santiago is still valid because it seeks to awaken humanity's charitable conscience. A better society is built with better individuals." Sylvina Balmaceda, Mendoza. Director of the Manuel Belgrano Public Municipal Library. "The teacher Santiago Bovisio. An immigrant, a history, a book." The teacher who set off from Vigevano" […] "Biography of a Vigevano man with honours abroad." Cover of the newspaper L'informatore, Vigevano, Italy, 2006. "The book shows us that Don Santiago's goal was Human Development […] This man possessed from a young age the spiritual capacity that allowed him to build his work." Lily Sosa de Newton, Buenos Aires. Full Member of the National History Academy and Outstanding Culture Figure of the City of Buenos Aires. "Don Santiago is the way into a world that makes us aware of our possibilities [...] This reading enriches us. It is a history of deep spiritual poetics to be discovered." Dr. Alicia Duo, Los Andes newspaper, Mendoza, 2006. "Don Santiago was a teacher in the broadest and deepest sense of the word. He transmitted a universal teaching for all human beings who, along diverse paths, wish to live according to the more spiritual, inclusive and comprehensive ideal they long to attain." Writer and journalist Mercedes Fernández.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 589

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

FABIANA MASTRANGELO

Santiago Bovisio

The Teacher Life, Work and Testimonies

Mastrangelo, Fabiana Santiago Bovisio : the teacher : life, work and testimonies / Fabiana Mastrangelo. - 1a ed. - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : Autores de Argentina, 2025.

Libro digital, EPUB

Archivo Digital: descarga y online

ISBN 978-987-87-6657-7

1. Ensayo. I. Título. CDD A860

EDITORIAL AUTORES DE [email protected]

Index

Foreword

A Clarification

Part One

Notice for the Second Edition

By way of a foreword

Introduction

Childhood and Adolescence

The first years in the Americas, “the chosen land”

The work begins

Souls awaken in Rosario

“Rosario, the wheel that set the expansion in motion”

“The Years of Preparation”

“In the education of souls, there is not a second to be wasted”

Colegio Leo Bovisio

A new stage in the road

The expansion of the work

Interview with Omar Lazarte – 2001

Chronology of the life and work of Santiago Bovisio

Part Two

A Tribute to Spiritual Friendship

Conversation with Joaquín Bovisio

Carlos Emilio Plüss, “The fisher of souls”

Biography of Santiago Bovisio

Conversation with Abraham Gurfinkel

Conversation with Amelia Bovisio

Conversation with Beatriz Caselli

Conversation with Luis Uhalt

Conversation with Dora Holzer

Conversation with Sara Davidson

Conversation with Paul Güida

Conversation with Juan Carlos Ginepro

Conversation with Enzo Casalegno

The Maitreya’s Return

Sources and Bibliography

For my parents, who passed down to me

their love for Don Santiago and his Sacred Work,

through the spiritual truth of his life.

Foreword

Don Santiago’s1 message and his sacred work are universal. This is the main reason why I am publishing Santiago Bovisio, The Teacher, which includes the second (Argentine) edition of the book Don Santiago, Life and Work of Santiago Bovisio and the first edition of Remembering Don Santiago. It is a sacred duty to permit that everybody can read the spiritual riches of the words contained in his disciples’ testimonies.

Don Santiago once said: “From the year 2000 people will start to talk about me.” In 2003 I published the first biography of the founder of Cafh, el Señor2 Santiago Bovisio. My intention was to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of his birth with a book that would attempt a first approach of his life and work. With the book presentations, his life and work then toured numerous Argentine towns and cities (Mendoza, Godoy Cruz, Rosario, Tucumán, Tunuyán, Buenos Aires, Salta, San Luis, Embalse and Santa Rosa de Calamuchita), and other countries (Italy, Bolivia and Costa Rica). The book was also declared of cultural interest by the cities of Mendoza and Godoy Cruz, and editions were published in Bolivia (2003) and Brazil (2007), the latter translated into Portuguese.

Santiago Bovisio,The Teacher includes some of the material compiled in the research that I began in 1996, at the invitation of Omar Lazarte to write the history of Cafh. The initial goal of the project was to write two books: one about the first part of the history of Cafh, corresponding to its first Spiritual Director, Santiago Bovisio; and the other, referring to the second Spiritual Director, Jorge Waxemberg. The idea was to integrate the teachings, the lives and the work of both men. In the end I wrote the book about the first Spiritual Director of Cafh, because Jorge Waxemberg felt it would not be fitting to write a book about his work, even though he was invited to do so on numerous occasions, before and after the publication of Don Santiago.

Historic time, like life, is dynamic and diverse. Thus, for example, the sacrifices our grandparents made, the ways they entertained themselves, are different from ours. True understanding of the testimonies comes when we visualize that dynamic, contextualized and diverse dimension of spiritual experiences. I suggest that the reader should not generalize here, believing that what works for one person works for everybody. This can skew the vision of the spiritual phenomenon and the riches contained in the testimonies.

Just as Plato’s master, Socrates, is present in his Dialogues, Don Santiago is present in Remembering Don Santiago. He was essentially a teacher and he chose the Americas for his work. His work reflects this. He created Cafh (a path of inner development), the American Spiritualist University of Rosario, the General San Martín Education Union, the Colegio Leo Bovisio (Embalse, Córdoba), the Escuela Merceditas de San Martín (Mendoza), among other works.

Santiago Bovisio defined himself as “a master of teaching.” This discipline consists of strategies that a teacher uses to convey a teaching or bring about significant learning in the student. In other words, teaching is a means of bringing to people the word, the method or the silence that is needed to develop the disciple. The educational role and the teaching of Don Santiago are present in the different conversations and written testimonies, because an essential focus of his work was to teach to live, and he created a method for this.

One of those who had the blessing of conversing with Don Santiago was my father, Hugo Humberto Mastrangelo. He joined Cafh in Rosario in June 1959. He said of the first time he saw Don Santiago: “It was in 1958. I was accompanied by my Superior, who had prepared me beforehand. He told me a lot about him and that day he said, ‘You are going to meet a Saint.’ I was carrying a letter from a candidate3 and Don Santiago asked me to read it to him. As I read, he looked straight at me, deeply. Then he said: ’Now I know where I know you from, gringo.’4 I asked him immediately: ‘What’s that, Don Santiago? What do you mean?’ And he replied ‘Sorry about the comment.’ It was the first time that we had met, in this life, at least.”

The reader may deem it “subjective” that I put this short testimony from my father at the start of the book, and they would be right. For me it is an act of spiritual gratitude because for as long as I can remember he spoke to me about Don Santiago. My father had a black and white photo of a gentleman in a suit, a serene face. This photo was on his bedside table. In my mind as a child the question always arose: “Who is that man?” To which he would answer: “When you’re older, you’ll find out.”

When I “was older” —a teenager—I began to learn more of the “sacred history of Don Santiago,” through my father’s stories which, for me at least, belonged to a heavenly world. I only heard his word, my mother’s, and that of their friends. Oral tradition and testimony were the shared space of those tales. There were no books or documents I could read to find out more, and this increased the legend.

What attracted me was the “enthusiasm” with which my father and my mother explained to me not only the life and work but also, especially, the essence of his teachings and doctrine. They taught me to transcend the personal visions that prevent us from knowing and living profound truths. They taught me to see the light that is behind Don Santiago and not just focus on the physical Don Santiago. I never met him because he died before I was born, but I feel I have known him my whole life.

I must give special thanks to Omar Lazarte because he invited me, in my capacity as a historian, to work on the History of Cafh. This work allowed me to discover sacred archives that enriched my spirit and took me to a time when the force of a transforming past became present and dissolved the temporal variables that limit human understanding.

In this sense, a comprehensive vision of history encourages me to write these lines. Every stage has a teaching that completes and complements the previous ones. Far from opposing them, they are integrated and included like parts of a hologram. Every human can connect with a part of that whole when spiritual necessity and context require it. In this regard, Michel Foucault,5 in his description of the history of truth in general, distinguishes between demonstrative truth and the truth-event.

Demonstrative truth is confirmed by scientific practice; it is the truth discovered with a method and in which a subject-object relationship exists. It is found in the doctrinal order and it is possible to affirm it in experience. Since the Renaissance, this truth has increased its prestige with scientific-rational thought and has detracted from truth-event, as Foucault says “truth-knowledge […] leeched off truth-event.”

The truth-event is revealed. It is a truth that is not repeated, it has its geography, its time and its privileged, exclusive messengers.6 That truth possesses the force of the connection with the divine and those who come into contact with it are immediately transformed because they receive the force of a sacred lightning bolt. This truth moves as quick as a flash, it is tied to the Kairos, which is the occasion and the opportunity that we must harness. For this reason, it is a truth that needs to be grasped, explained, written. This is the ultimate goal of writing about Don Santiago.

The demonstrative truth and truth-event are not opposed; they complement each other. This vision of the truth and of history is integrating and opens the path of diversity. Because of our particular characteristics, we can live one truth more than another, and we can also harmonize with those who live another truth more. And if we remain in a stage or in an aspect of reality, we become paralyzed and dogmatize because we do not understand that the stage that comes after the event is derived from it and explains it. It is the subsequent development of the initial idea. Furthermore, if we put one truth up against another, we return to the past of the pair of opposing poles that closes human understanding and the path towards diversity.

The event has its frame of action in the historical and metahistorical plane. The former plane is lived by those who were witnesses and protagonists of the past. The latter plane is projected in those who were not contemporaries to the event but experience and identify with the force of the idea and the feeling of that moment. Thus, in metahistory, the event is updated and the transcendence of the historical fact is confirmed. It is important to clarify that not all past actions act on the metahistorical plane. This plane occurs in significant events that transcend particular or personal interests or circumstances and the force of its ideal breaks the spatial and temporal variables.

For example, for over 2000 years, men and women were subjects of the King, without individual rights. This situation was transformed with the French Revolution, which established the ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity, and the condition of citizen without distinction of creed, race or social situation. Those ideas spread around the whole world and influenced the constitutions and forms of government of the new States. The strength of those ideas and their area of expansion transcended the space (France) and the time (1789) and remain relevant. In the spiritual order we can mention as an example Saint Francis of Assisi, who 1200 years after Christ lived the ideal of “being poor among the poor” and, especially, experienced the Christian transformation.

In both cases, the French Revolution and the life of Saint Francis of Assisi, the event is updated, that is, the past becomes present through the strength of the ideas made lives in different spaces and times. This situation occurs on the metahistorical plane.

Returning to the truths that Foucault classified, this book is written with the aim of affirming the truth-event revealed by Don Santiago. The testimonies demonstrate that that truth gives a strength that is maintained in whoever introjects it and identifies with it. “Strength, tranquillity and love are the salvation of the world,” said Don Santiago.

We are all part of the truth. Those who lived under the miraculous aura of his life and his work had the privilege to witness that truth. Those who have the mission to affirm that truth receive the spiritual energy of that transcendent, unique time, that lightning bolt from the heavens. Those who develop the doctrine derived from the event bring to life the truth, knowledge that they transform into experience.

Don Santiago made various Cafh superiors speak at a spiritual retreat, in the teaching hour. At the end he said “El Señor Jorge has the Doctrine of Cafh” because he was the only one who had fully interpreted it. That was confirmed in the following years when, as Spiritual Director of Cafh, he continued to broaden extraordinarily the doctrine. It was a necessary and transformative complement for the development of the work created by Santiago Bovisio.

As I wrote in the first paragraph, everybody is able to receive and bring to life the truth-event transmitted by Don Santiago and the demonstrative truth developed by Jorge Waxemberg. I stress the word “everybody,” because it reflects the proposal of openness and expansive, participatory love to which we are summoned by the third Spiritual Director of Cafh, José Luis Kutscherauer.

Fabiana Mastrangelo, 2008.

1 Santiago Bovisio’s early disciples called him “Don” Santiago with a sense of affection and respect. This expression belonged to the oral tradition of Cafh members in relation to the founder.

2 In the context of the history of Cafh, the term “Señor” or “Señora” is a respectful form that is used for those who have reached a high degree of commitment with the Work.

3 Candidates were those interested in entering Cafh.

4 “Gringo” where it is used in this book refers to an Italian immigrant in Argentina. (TN).

5 FOUCAULT, Michel. El poder psiquiátrico, F.C.E, Buenos Aires, 2007, pp. 265-274.

6 The geography of the Don Santiago event is Buenos Aires, Rosario, Córdoba and Mendoza; its time 1939-1962; and its privileged, exclusive messengers give the testimonies.

A Clarification

Part One of Santiago Bovisio, The Teacher consists—as mentioned in the Foreword—of a biography that I wrote based on historical research, published in 2003 with the title Don Santiago, vida y obra del Señor Santiago Bovisio. As the first edition is out of print, this is included as a second revised edition with the intention that new readers may access the spiritual riches of this special person.

Part Two, Remembering Don Santiago, is published for the first time here and is made up of writing by and conversations with Bovisio’s disciples. It is a compilation of the testimonies that I gathered as a historian in my research process.

The written testimony and the interviews with the disciples are visions skewed by time and personal perspectives. Thus, there may be different perceptions on the same theme or occurrence. This is the value of the testimony, as it opens a diverse and free range of life experiences. The sources of the historical research are, precisely, those experiences that the historian takes care to corroborate with other sources and include in a biographical account close to the historical truth.

Moreover, readers of Don Santiago, vida y obra del Señor Santiago Bovisio asked me, on numerous occasions and in different cities, about the meaning of terms related to Don Santiago’s work. This edition also includes testimonies on Cafh’s tradition and organization. Explanatory footnotes are included where such concepts appear for the first time.

Although this publication reflects the trajectory, purpose and meaning of Cafh, a work founded by Don Santiago, I thought it fitting to explain it briefly in these first pages.

Cafh was founded in 1937, in Buenos Aires, by Santiago Bovisio (b. 1903, d. 1962). The Second Spiritual Director of Cafh was Jorge Waxemberg, who held this position from 1963 to 2005. In 2005, José Luis Kutscherauer was elected as the present and Third Spiritual Director. The Work of Cafh has been taken to various Argentine provinces and to the following countries: Germany, Australia, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Spain, the USA, France, Israel, Italy, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Switzerland, Uruguay and Venezuela.

The term Cafh is not an acronym, it is an ancient word that has various meanings, including the effort of the soul to reach the union with God, and the self-possession that this effort implies. Cafh’s main task is the integral development of the human being through self-knowledge and by building harmonious relationships with life, the world and the divine. From a social perspective, its purpose is to promote the development of society through participation, teamwork and everyday actions that each individual can do to relieve the pain of thousands of human beings and work for the common good.

Part One

Notice for the Second Edition

This book is based on historical research, with the testimonies of those who knew Santiago Bovisio making up much of the text, in addition to pieces written by his early disciples, Carlos Plüss and Abraham Gurfinkel.

If we were to limit the historical approach used in this work to a simple chronological, schematic list, we would end up with a book that was too objectifying and we would miss the chance to capture the spirit of Santiago Bovisio. Instead, this spirit ultimately occupies the core of the book thanks to the testimonies mentioned. These are developed using the biographical method that “takes in people’s experience precisely as they process and interpret it.”7

This means acknowledging that in a historical work, subjective elements are part of the historical truth and, as such, cannot be ignored in the research process. Thus, from an inclusive approach, the subjective cannot be separated from the objective, nor the text from the surrounding sociocultural context in which the events occur. Edgar Morin, extolling this global vision of human life, states: “Our point of view supposes the world and recognizes the subject […] The subject and the object emerge like two ultimate, inseparable consequences of the relation between the self-organizing system and the eco-system.”8

The author’s absolute neutrality in her work was an aspiration of ancient approaches. Today, that essential objectivity is complemented with the self-awareness of the author who knows her point of view and her own interpretation, which also has to be clearly set out in the work. This healthy balance prevents us from falling into a panegyric, that is, creating a laudatory work of the person studied, and also prevents us from making a simple chronological, schematic list, as I said above.

For this reason I must say that, although I did not know Santiago Bovisio personally, I was born in a home in which his life and work were everyday subjects of conversation and reflection.

The above reasons oblige me to notify readers about the different “voices” they will find in these pages: the voice of the researcher who seeks to specify and substantiate with sources the historical matter presented; the voice of the testimonies that bring us closer to the feelings and interpretations of the protagonists of the era; and, last of all, the voice of those who seek to join together and explain the historical events, in the context of the life philosophy that gives sustenance to Cafh, the path of human development that Santiago Bovisio founded.

Interpretative plurality and the limits of this work

One of the fundamental notions that Santiago Bovisio taught was “to give doctrinal freedom to the soul”9 and to respect every human being’s freedom of consciousness. For this reason, I have respected the diversity of testimonies I have found on Santiago Bovisio’s life and work. My intention is that readers may reflect freely on the life and work of this exceptional person, without imposing a “single thinking.” We must not confuse history with doctrine, testimonies with proposals, or past with present. It is also important to understand the “philosophy of history,” that is, the origin and evolution of thought separately from certain sociohistorical contexts.

Santiago Bovisio was a human being with beliefs, mistakes, a language and a way of perceiving reality. Every reader is entitled to consider as belief what for others is experience or evidence. However, I must issue another advisory note: this presentation is incomplete, that is, there is much left to investigate and reflect on his life and teaching. In the first edition of Don Santiago (2003) I set myself a goal: to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of the birth of Santiago Bovisio with a book that would essay a first approach to his career. I achieved that goal.

7SAUTU, Ruth. El método biográfico. La reconstrucción de la sociedad a partir del testimonio de los actores. Editorial Belgrano, Buenos Aires, 1999, p. 23.

8 MORIN, Edgar. Introducción al pensamiento complejo.Gedisa, Barcelona, 2000, p. 64.

9 Registration in the National Register of Religions. Form No. 2, Annex 3, p. 8, Buenos Aires, 20 April 1989.

By way of a foreword

Jorge Waxemberg, continuing the work founded by Santiago Bovisio, and the Second Spiritual Director of Cafh, wrote some words in 1969 in homage to the Founder. I transcribe them here by way of a foreword, because of their relevance today and because they sum up the spiritual depth of the life of Santiago Bovisio and his work, Cafh:

Seven years is sufficient time to evaluate the life of a man. But in the case of Santiago Bovisio, we are still too close to his figure, to the memory of him, and especially, we are determined by the same era in which he lived. To some degree, these factors limit the timeline necessary to position an existence such as his, one that was life, teachings and work.

I have no intention to write a panegyric; I do not believe in that sort of homage. Furthermore, the close bond that joined me with Santiago Bovisio and my affection for him lead me to run the risk of removing his figure from the time in which he lived and make it my own, limiting his dimension to the influence that he had on me. Nor will I attempt to make a judgment on him, for this same reason; it is not my place to do so.

However, the particular and extraordinary way in which he roused and guided my concerns, the atmosphere of inner freedom in which he taught me to develop my spiritual possibilities, the capacity to think, feel and realize, commits me.

If Santiago Bovisio had been just a friend, a guide or an advisor, my commitment would be merely to the memory of circumstantial matters, or the memory of his notable gifts as spiritual director that he shared with a limited number of disciples: the direct influence of a person cannot go beyond a small circle. But it is not that type of influence that counts. The value of an existence is not conditioned to anecdotal memories, to personal traits, to the small history of a life. The life of someone who has committed himself with human beings comes out of his time frame and projects into a dimension that we cannot determine today.

Santiago Bovisio’s commitment to all human beings commits us today with our time and our world. It forces us to renounce making a property of him and his teaching, interpreting his life and his thinking according to our particular approaches.

We have little information to write his biography. He did not tend to speak about himself; in his relationship with us he acted in such a way that it did not occur to us to ask him questions about his past.

In reality, it is not the information about someone’s personal history that can totally account for who they are. Life cannot be enclosed on a file card. When that life is only the starting point of an idea, biographical notes reduce that idea, denaturalize it.

Santiago Bovisio was born in Bergamo, Italy, on 29 September 1903; he was schooled in Turin and Venice; he left for South America on 10 January 1926.

It was on this continent that he would fulfil his mission, find his disciples, embody his ideas in a spiritual work. But the chosen land only opened its arms to him many years later; it gave him his children, but only after testing him severely. He did not bring with him economic means that would facilitate his task; nor did he use his uncommon intelligence to accumulate possessions and wealth. He wasn’t interested in that. However, many approached him to translate into material wealth the exclusively spiritual orientation that he gave.

Life offers us many paths and possibilities. But to effectuate an enduring work, we have to concentrate our efforts and live around a single goal, a single idea.

Santiago Bovisio founded Cafh on 3 March 1937. Since that day his life has been identified with Cafh; his thinking with the teaching; his fate, with that of his spiritual children.

His goal was spiritual, but years of work and patience were needed to separate, in his disciples’ understanding and aspirations, the truly spiritual concerns, from their desires of particular and personal realization. He did not profess dogmas or force people in any way to worship his person or believe in his teachings. But he sustained that a foothold is essential to achieve anything.

He gave his teaching when each person came into a position to assimilate it and realize it. He taught to think, to discern for oneself what one truly wants and the means at one’s disposal for achieving it. He removed from the spiritual concept its emotional and sensitive meanings, and its magical and occult implications, differentiating the possible from the demonstrable, the achievable by the intellect from that which transcends our capacity for understanding. But, above all, he guided each person towards the realization of their spiritual vocation within the broadest inner freedom. He left the confirmation of basic principles to the sphere of individual experience. The important thing is not to discuss what cannot be demonstrated, but to find the path to develop ourselves in pursuit of the plenitude we crave.

He did not use his moral authority, his personal realization, his knowledge or the respect that he inspired as a resource to be followed. Rather, he taught each person to advance by their own means, and to achieve for themselves the vision that is only revealed from within oneself.

He identified with oneself in such a way that the teaching seemed to come from within oneself.

He distrusted spiritual realizations that are not reflected in concrete facts. In this sense he was eminently practical, objective. He deeply respected all ideas, but he judged them by their evident results. Any idea that is not rooted in experience, any aspiration that does not translate into realization, is mere utopian idealism, time wasted that leads to confusion and scepticism.

He studied the different philosophical doctrines and experienced the fundamental religious paths. He taught to respect all people who, via different paths and confessions, seek the divine union according to their faith. Especially, beyond the differences in creeds, he showed the fundamental unity of the revelation that sustains them.

He taught that the highest elevation of love is renunciation and made this the path of love.

Cafh is the expression of that love; it is the synthesis of the idea, of the work and of the message that Santiago Bovisio conveyed.

Cafh is a meeting of souls who seek to develop and achieve inner freedom through a method suited to individual characteristics.

Cafh is open to all people; but it is not considered to be the necessary path for all of them. That would be to misunderstand human nature, individuals’ different vocations and possibilities. History teaches that no social structure or organized religion thus far has been universal, despite the tireless efforts of their followers to achieve this.

Each of the different social theories claims ownership of the truth for itself, but they can only conquer humanity by breaking it up.

Successive wars and social and religious conflicts have ultimately left us more alone and confused, to the point where we no longer know who to turn to or where to look for support. The most beautiful spiritual, social and economic doctrines have systematically mocked the self, in the facts, forgetting that it is that self who can give them meaning. Meanwhile, the climate of violence and crime gets worse and worse. The easiest path is to search on the outside for those responsible for our ills, the scapegoats who absolve us of guilt.

Santiago Bovisio did not think that the success of Cafh would lie in having a large number of members one day. What is important is to grow in direct experience, which makes a theory a reality.

Cafh chooses the difficult and sometimes painful path of each person searching inside themselves for the root of evil, ignorance and confusion, and finding along the same path a better attitude to life, values that allow us to understand more thoroughly what we are, our possibilities and our path.

Renunciation is the idea that underpins the teaching of Cafh. The word renounce is not enough to define the idea of the renunciation that the teaching of Cafh conveys, but we cannot find a more appropriate word to express it.

The attitude of renunciation leads to a behaviour, a position towards life and the world, and also a vision that gives us the chance to expand our state of consciousness.

As long as we set the individual against society, personal rights against social responsibility, subjective reality against objective world; as long as we separate the spiritual world from material reality, and spiritual values are only the ideal scaffolding with which we cover a reality in which we live and fight without morality and without God, the world will also be divided and its problems will inevitably lead to more pain and destruction.

Cafh does not put forward its teaching as another solution to be added to the long list of remedies for humanity. Human problems are not cured with solutions, when by solution we understand a system that is opposed to another system. We think that today we need a new inner dimension that will allow us to understand the nature of the problems that we endure; in short, we need to grow internally, reach a state of consciousness that translates into a new individual and collective reality. One way or another, all human sectors are currently seeking that development, finding their way in the dark, in pain.

To develop internally and achieve a broader state of consciousness, it is necessary to have the right tools and a technique of inner work. The path of renunciation begins by seeking inside ourselves the root of evil that we want to resolve outside and resolve it in our relationship with ourselves, with those around us and with society.

If we focused only on ourselves we would live in unreality; personal happiness does not exist disconnected from collective reality. Our renunciation must be expressed evidently in our attitude, our behaviour and the effects that we generate in the totality of the means in which we live. As attitude and perception, we could say that renunciation is manifested in presence, participation and reversibility.

Presence, because we focus on the current, total reality, without escaping in pursuit of a particular separate happiness: we are present.

Participation, because in remaining present, our inner reality expands and covers all reality: human being, world and universe.

It is good that we are aware of human problems; but mere knowledge of them is not enough to respond to them properly. Only when we participate do we realize that we cannot isolate our problem from everyone else’s problem. Consequently, we become responsible.

Furthermore, we cannot separate what we are from what we do. Extraordinary technological advances show our notable outer conquests, while separateness, destruction and violence reveal our inner reality.

To participate means to expand our consciousness of being: being is being in everyone. This participation would only be the dream of visionaries if it were not expressed in a conduct in keeping with all human beings, their lives and their problems.

Reversibility in practice means overcoming our tendency to reduce our vision to look at only one side of things. Our thinking works within pairs of opposites: to be or not to be, to win or to lose. So it is that we associate renunciation with a loss. But life has more faces than just the obverse and reverse. Reversibility reveals to us that to lose is to win, to not be is to be and to renounce is to free oneself. In contextualizing our perception in greater spaces, we achieve an increasingly broader sense of being, possessing and realizing.

Santiago Bovisio—Don Santiago, as we called him—did not seek to endure through fame or wealth; but he left us an inner wealth that, for us, does not depend on the vicissitudes of life, nor does it fade with time.

Jorge Waxemberg

Buenos Aires, 3 July 1969

Introduction

This first part covers the life and work of Santiago Bovisio, founder of Cafh. His disciples affectionately called him “Don Santiago,” and this is how I refer to him in this text. His life was a message about a new way of thinking, feeling and acting, and he chose Argentina to spread his message. So it is that the first line of the first course he wrote in 1937 was: “New ideas and works are prepared for the world.” What was new about them? A universal thinking, for all human beings, which stimulated capturing what was good, real and applicable about the new ideas and different philosophies.

The universality of his thinking led to an eclecticism in the broadest sense of the term,10 that is, distinguishing what is considered best of each doctrine. This should not be understood as mere accumulation of a mosaic of ideas, which would be the case of syncretism, but as complementary, dynamic visions that make it possible to construct a holistic scenario of reality, and thus avoid any kind of dogmatic crystallization and fragmentation of human coexistence.

Don Santiago made his lifestyle from respect for and deep understanding of diverse philosophies. That understanding emerged from his rapport with souls, with the world and with life. The teaching that he passed on in his everyday actions or summarized in his writing emerged from the specific needs that people needed, that humanity itself needed. This was the essence of what made his teaching so dynamic, rich and universal. For this reason, he took from each philosophy or from sacred universal tradition what a person or a group of people needed for that moment. He never wanted to publish his writing in books or journals, because he thought that this might eventually become a dogma that forgot the true needs of the souls and of humanity as a whole. His incredible inner freedom and his love for people were the stars that guided his thinking.

This immediate understanding of what human beings needed emerged not only from his deep spirituality but also from his “rare intelligence,” as Jorge Waxemberg wrote (1969). Don Santiago had the gift of clairvoyance, of knowing what afflicted the sick, of knowing the past of a person, etc. Testimony of these and other gifts can be found in the accounts of his disciples and relatives and, to a greater extent, among those who knew him in the early stages of his life.

I believed it was necessary to select and include some of those testimonies because this sort of thing popped up in ninety percent of the in-depth interviews. Therefore, those stories were a reality for the vast proportion of the witnesses of the past and, in order to write a biography as close as possible to the historical truth, I thought that they should be included, regardless of any explanation that science might give these paranormal phenomena today.

Thus, for example, when Sputnik, the first unmanned spaceship, took off, Don Santiago said: “I will not live to see the wonders of the new space age that has begun, but you and your children have no idea what you will get to see.”11 On this point, his disciples mentioned to him that they had very much enjoyed one of his latest pieces of writing, to which he replied: “Yes, but what I really could have put in isn’t there.” Astonished, his disciples asked him why he hadn’t put it in, and he said: “Because you would have laughed at me […] imagine if I spoke to you of pressurized cities in space.”12 We must remember that at that time (1962) the concept of “pressurization” was not widely known and no experiences existed of humans spending long periods in space, as happens today.

On another occasion, someone told Don Santiago he was going to have an operation, and right then Don Santiago asked him for a pencil and a piece of paper. He drew him a picture and said: “Here is what the trouble is, this is what’s bothering you.” That person took the piece of paper to the doctor, without telling him who had drawn the picture, and he said: “A very good radiologist did this drawing, that’s exactly where the problem is!”13

Don Santiago was aware of both the fascination and the scepticism that his powers could have on some people. In the latter case I can present the testimony of his son, Joaquín: “I remember when we went to a friend's wake and dad said to me: “His astral body had the wish of life in his mouth.” So I asked him, “Those things that you see, how do you know you’re seeing them and not just imagining them?” And he replied, “I’ll never know, but for me they’re as real as when I see you.” Joaquín reflected: “My father accepted my scepticism.”14

But he gradually stopped mentioning this sort of thing, and those who knew him in the last ten years of his life no longer heard these testimonies. Jorge Waxemberg, when asked about the subjects that early members of Cafh worked on, said: “The subjects that I heard when I joined Cafh were related to supraphysical phenomena. The subjects that I heard from Don Santiago from then on had nothing to do with that. Specifically, they were subjects related to people’s spiritual unfolding.”15

At a given moment, Don Santiago put a stop to it. He said: “I stopped practicing clairvoyance when I realized that I had a thirty percent margin of error.”16 Beatriz Caselli commented: “He had the gift of clairvoyance and conscious contact with the astral world. He gave the founders of Cafh clear proof of his powers. But in the aesthetic-mysticism of Cafh he didn’t find such practices. That’s why he paused his demonstrations and spoke no more of them; he gave no importance to those natural gifts that he had.”17

On one occasion, a group of young Cafh members were reading a book by Paul Brunton on the teachers of India. These young men were in awe at all the types of paranormal phenomena that these teachers experienced. Don Santiago listened to them in silence the whole time the young members were reading the book, until one day he broke his silence in a very particular way, when he commented to Jorge Waxemberg: “I remember that one afternoon I found you writing on a piece of paper and you gave it to one of us to read at one of our lectures. The piece of paper had a number of phrases that said: ‘On such a day, of such a month, of such a year, I did this; on such a day, of such a month, of such a year, I did this…’ It listed all the things that he had managed to do, an enormous number of incredible things he had done. For example: ‘I controlled my heart rate18 for so much time, I stopped my breathing for so much time, I did this… I did the other…’ Things like that that we had read other teachers had done. At the end, he said: ‘But I realized that all that did not bring me close to a true spiritual realization, because if I stopped doing those exercises I lost that power.’ So the path is another. He finished there, we spoke no more of the matter.”19

For Don Santiago, it was vital to make the development of the human being an evident, demonstrable, permanent truth. He taught that it had to rest on true facts, that the spiritual life had to be demonstrated with evidence, that only an evident knowledge can be considered a truth. He always encouraged his disciples to make spiritual unfolding real, even in the metaphysical order. He taught that only supraphysical phenomena that are evident or can be demonstrated should be considered real. He thought that there was already a possibility of demonstrating some of those phenomena, but that until this occurred, they had to be understood as possibilities and not as a reality.

His intention was that those who came to Cafh did so to find, by their own means, the path to themselves. He wrote to Carlos Plüss: “Before, I moved away from the friends of the world, because I saw that they only sought out my psychic gifts, but now I have to hide from many of our spiritual friends so that they will learn to walk by themselves.”20

For Don Santiago, inner freedom was only attained when human beings found for themselves the meaning of their lives and the means to make that meaning reality. On this line of work he was a veritable pedagogue, adapting his teaching strategies to the needs of the souls so that they might discover their path and walk it.21

He was a free being, and for this reason it is not easy to write a biography about someone who spoke so little about himself and “did not seek fame or riches.” According to his disciples, Don Santiago was committed to the development of souls. Most of those interviewed remember the following phrase that he repeated on different occasions: “Don’t follow me, follow the light that is behind me.” He taught people to not follow a person, but to follow the vocational feeling and the ideal that shone within them. Spiritual life was to Don Santiago a fantasy if it did not translate into an evident, demonstrable truth. For him, truth flowed from experiences. For this reason, as mentioned above, he systematically refused to publish the texts he wrote, despite his disciples’ suggestions that he do so.22

On this occasion, the publication of his life and work is done from a historical perspective because great work has been done to gather information and analyse documents as the foundation for reconstructing the past. Furthermore, the historical data presented here is not limited to a mere schematic representation or chronological enumeration, but rather it is interpreted and analysed in order to understand its dynamics and its connections.

From this approach a global perspective of history is seen that incorporates the events of the past in the life story, not in a fragmentary and sporadic way, but attending to its correlations and projections in time. Thus, the themes investigated have sides to them that transcend the historical fact in the strict sense. Such sides include the philosophical side, the mystical side, the pedagogical-didactic side, the social side, the economic side, to name just a few. This web of relations necessarily leads to an interpretative plurality that permits that global conception of the historical event.

The documents used are oral and written sources. These have been incorporated using the biographical method that consists of: “the systematic use and collection of vital documents that describe moments and turning points in the lives of individuals. These documents include autobiographies, biographies, diaries, letters, obituaries, life stories and histories, chronicles of personal experiences.”23

Interviews used in this study include in-depth interviews with Bovisio’s disciplines and relatives. Special care was taken in the interviews to note faithfully the ideas expressed by Don Santiago and not their interpretations. However, oral testimonies always have a subjective side to them. For this reason, in all cases the source is quoted in a footnote. Relevant historical information has been corroborated both in writing and orally.

The written sources are of diverse origins. Firstly, there are some of his dreams and meditations, and transcriptions of his letters by his disciples. Secondly, there is the writing by his first disciples, Carlos Plüss and Abraham Gurfinkel. They wrote in 1978 and 1979, respectively, with the intention of leaving a testimony of the life and work of their friend and teacher. I also consulted the institutional archive of the Cafh Foundation, and newspapers such as Corriere di Vigevano, La Capital and La Tribuna of Rosario, and La Nación of Buenos Aires.

Elsewhere, the contribution from the family archive of Joaquín Bovisio deserves particular attention. A large number of the photographs published here are from this archive.

Far from being exhausted, documentary sources will no doubt continue to be researched. The opening of new archives will make it possible to broaden the range of Don Santiago’s life and work.

Lastly, I should define who “Don Santiago” was. However, I believe that there will be as many definitions as readers of these pages. A re-reading might even reveal a new vision of the “being of Don Santiago.” I can only offer some definitions that were given by those who knew him, and venture one of my own without any intention for it to be definitive because history, as Croce says, is “related to the current needs and the present situation in which those events reverberate.”24

Don Santiago “expressed himself differently with each person […] he responded to the other person’s receptivity. He was one person with the doorman, another with Plüss and he was a different person with me. It wasn’t that his voice or his gestures changed, but the way of speaking or even the type of relationship he established as Spiritual Director […] was something he did based on what one needed.”25 These words from Jorge Waxemberg illustrate the impossibility of drawing a picture of Don Santiago because, precisely, he did not relate with people through his personality but through his free, loving and participatory self.

In his presence, souls experienced a profound spiritual communion and, at the same time, the awakening of a different reality. They felt that the veils (prejudices, limits, attachments, pains, etc.) that covered them disappeared at that moment, and a real “meeting of souls” was established. This was his external and internal work. External because he founded Cafh which “is a meeting of souls seeking their inner liberation through an external individual method” and internal because he made this truth his life. All the oral and written testimonies express, in different ways, that climate of freedom, participation and love that his presence inspired. His disciples and friends sought that encounter intentionally because “the best” that was in each being flourished there. The latent potentialities of the souls became evident to them and thus they recognized, by themselves, the possibilities they had to travel the path of human development.

I quote below a selection of testimonies that answer the questions: What did you feel during the first encounters with Don Santiago? and What did you experience inside in his presence? The purpose of these testimonies is to broaden the perspective of the being of Don Santiago.

“Being with him meant being totally alert to myself […] It was as if being with him, even thinking about him, gave you an alert about yourself, as if you were watching your own inner x-ray permanently” (Jorge Waxemberg, Buenos Aires, 1998).

“With his life he taught us the technique of realization that fundamentally lies in disappearing as an isolated person, in breaking the labels of separateness that only drive people away from each other. He showed us this in relation to his disciples, since in his relationship with us he disappeared to such an extent that it never occurred to us to ask him questions about his past” (Carlos Plüss, Buenos Aires, 1978).

“He was the Master of clear spirituality. His inner freedom and the freedom that he taught to live went to such an extent that his disciples came from the most varied religious and philosophical backgrounds and communication in the master-disciple relationship was established immediately and flowed without obstacles from that, his inner freedom” (Abraham Gurfinkel, USA, 1979).

“The first time I saw him I did not notice anything particular in him that set him apart, save the shine in his eyes and his penetrating gaze when he looked at you, but it was sweet and soft when he gazed at your aura or when he told us about an astral presence that had visited us […] His way of being was extremely simple and natural […] This naturalness with which he acted always obeyed the needs of those around him […] He was always very polite in his manners, without affectation. His dress was modest and impeccable […] His was a presence before which you lowered your gaze, because you felt that you were before something bigger and, at the same time, you got close to his paternal heart as if to the most human being […] he was not on a pedestal, nor did he feel he was, he was by our side with humility and simplicity” (Mrs. Beatriz Caselli, Embalse, 1998 and 2001).

“Without speaking, he told us a load of things. I’m fifty-one and I’ve never seen anything like it since, he was like a sun. And his figure was like pure energy; we’d see him and do what we had to do without his saying anything” (Enzo Casalegno, Embalse, 2001).26

To limit the being of Don Santiago to one definition would be to forget the message of universal love that he bequeathed with his life. He gave his life, without limits, without conditions and without asking for anything in return. Each person took what their selves needed at that moment. For this reason, both those who lived by his side in the past, and those of us who study his life today, take the side of the self of Don Santiago that fits with our interpretations and spiritual needs. This is what is called cognitive and propulsive retrospection, that is, we look at the past not only to know it, but also to project ourselves to the future in a permanent awakening in keeping with the spiritual symphony lived in other times.

To sum up, I can say that Don Santiago came to Argentina to propose a new way of thinking, of feeling and of acting. The establishment of his mission was gradually revealed, as he developed his soul, penetrating the Argentine idiosyncrasy and listening to his disciples and the longing in his heart. All this implied an enormous human effort for him. His work was a process that took him all his life and its beginning was slow and tough. Then, in the last years of his existence, a dynamic process occurred that was projected in the expansion of his work. This work was continued and multiplied by the Second Spiritual Director of Cafh, Jorge Waxemberg.

Today, continuing with this expansive movement, I publish this biography27 of Don Santiago with a rich message. I suggest that readers attempt to discover that message and avoid any kind of reductionism that the limits of language seek to impose.

10 FERRATER MORA, José. Diccionario de Filosofía. Alianza, Barcelona, 1982.

11 WAXEMBERG, Jorge. Interview. Buenos Aires, 1998.

12Ibid.

13 BOVISIO, Amelia de. Interview. Buenos Aires, 1978.

14 BOVISIO, Joaquín. Interview. Buenos Aires, 1997.

15 WAXEMBERG, J. Interview.

16 BOVISIO, J. Interview. Jorge Waxemberg heard a similar story, with the same percentage, from Don Santiago. (Interview. Embalse, December 2001).

17 CASELLI, Beatriz. Interview. Embalse, 1998 and 2001. Beatriz Caselli joined the path in 1945 and joined the Community of Embalse in 1949. She was a teacher and principal of the Colegio Leo Bovisio. For this reason, she was very close to Don Santiago and his wife, Amelia, and was with them in the early days of the foundation of the school and the Community in Embalse, Córdoba.

18 On this subject, Joaquín Bovisio recalled that, when his father was on the farm of his good friend José Madariaga, the latter cast doubt on paranormal phenomena. Then, Don Santiago told him that he felt sick and José, who was a doctor, took his pulse and discovered that he didn’t have one. He was alarmed at this, and wanted to take him to the house immediately, but Don Santiago told him quite matter-of-factly that he had voluntarily modified his heart rate. (BOVISIO, J. Interview).

19 WAXEMBERG, J. Interview.

20 BOVISIO, Santiago. Letter to Carlos Plüss, 10 September 1948. Cited in PLÜSS, Carlos. Cafh en la Argentina. Buenos Aires, 1978.

21 On this aspect, see the interview with Omar Lazarte in this book.

22 GURFINKEL, Abraham. Biografía del Sr. Santiago Bovisio, USA, 1979.

23 DENZIN, N.K. Interpretative Biography, Qualitative Research Methods. Newbury Park: Sage publications, 1989. Vol. 17. Quoted by SAUTU, Ruth. Op. Cit., p. 21.

24 CROCE, Benedetto. La historia como hazaña de la libertad.FCE, Mexico, 1960, p. 9.

25 WAXEMBERG, J. Interview. 1998.

26 Enzo Casalegno was part of one of the first groups of students at the School in Embalse that Don Santiago founded. Therefore, this testimony reflects the perception of a child which today, filtered by time and experiences, remains inside him. When Don Santiago and Jorge Waxemberg travelled to Italy in 1959, Enzo was the only child at the school that Don Santiago wrote to personally. (This story is told in more depth in the chapter on the Colegio Leo Bovisio).

27 The narrative style and the method of this biography fit the definition given by Leonor Arfuch (2002): “The biography will move in an uncertain terrain between testimony, novel and historical account, the fitting to a chronology and the invention of the narrative time, the meticulous interpretation of documents and the imagination of reserved spaces that, theoretically, only the ego could reach.”

Santiago with his mother, Ester. Milan, 1911.

Source: Joaquín Bovisio

Childhood and Adolescence

Santiago Bovisio was born in the city of Bergamo, in the Lombardy region of northern Italy, on 29 September, 1903. His father died when he was very young. His mother’s name was Ester and, a few years after being widowed, she married a military man. Santiago did not want to go with them to the different European military destinations his mother’s husband was sent to, so he lived with his grandmother and his aunts, Antonietta and María, for most of his childhood, in the town of Vigevano, also in Lombardy.

Santiago’s grandmother “Doña Delfina.” Source: Joaquín Bovisio.

The grandmother’s spiritual influence

Santiago’s grandmother had a fundamental spiritual influence on his soul. Her name was María Delfina and she belonged to a traditional Vigevano family, the Bocca Corsico Piccolinis, and probably had a noble title. Don Santiago’s disciples recall that he referred to her as “la abuelita,” “grannie.” She was an extraordinary woman, renowned locally for her charity and generosity. Once, at Christmas, she had prepared the food and the table. The other family members had gone to hear midnight mass. Santiago and his grandmother had stayed, watching over the house. The boy gazed at the illuminated, decorated pine tree, contrasting with the opaque light of the kerosene lamp and the reddish reflections from the great traditional fire. His grandmother told him that the baby Jesus had been born and lay on the nativity scene covered in green, laid out on the high altar with his little hands open and arms out, as if inviting everyone. The young Santiago imagined how beautiful the town’s church would be that night. Don Santiago recalled: “In my little boy’s head, I could see the great naves of the church, full of lights, song, incense, and serenity.” A knock at the door interrupted the peace of that moment.

Santiago felt scared and hid in a corner of the dining room because he knew that that afternoon a very dangerous prisoner had escaped, and that also that same day a suspicious-looking man had been begging in the street. Before they left for mass, his family told the grandmother not to let anybody in, for any reason. But the old lady ignored those words and fearlessly headed for the door, and with a gentle face said: “This is our Lord.” She opened the door and recognized the fugitive, a very dangerous murderer. He was a short man, his big eyes hidden under thick eyebrows. Don Santiago recalled: “I only know that grandma serenely invited him in and that the intruder followed her like a lamb, his head lowered; she sat him at the table and served him as if he were the man of the house.” She also washed his feet, as was traditional to do for the first person to enter the house on Christmas Eve. Then she made him a packet of provisions, opened the door and said: “I’m going to give you a few lire, but then you must turn yourself in to the authorities.” Doña Delfina conversed with him, transmitting her love to him. The prisoner wept and embraced her. When he opened the door, he did not hesitate to follow the grandmother’s advice. He turned himself in and confessed that he had intended to kill her, but when he saw her and felt her love, he couldn’t do it. No one had ever treated him with such affection.

When his family got back, the boy told them what had happened. They all cried out in horror. But the grandmother smiled and replied: “The poor thing, he remembered his mother!” For a moment, that “poor thing” freed himself of his past burdens and recovered his dignity as a human being. That grandmother’s love pervaded his whole being.

Doña Delfina gave away everything she owned, to such an extent that her daughters had to lock her wardrobes because whenever a needy person asked her for anything, she would give them whatever she could find in there. It was the same with food, she did not hesitate to give a lunch, all ready to serve, to whomever knocked at her door and asked for something to eat.

Santiago with his grandmother. Turin, 1925. Source: Joaquín Bovisio

Santiago’s Aunts, Antonietta and María, in the house in Vigevano. Source: Joaquín Bovisio

Opening up to the divine during childhood

Santiago’s grandmother transmitted love and a profound trust in the divine. She embodied her love for God in a real love for her fellow man. This was the example that guided Santiago in his childhood and adolescence. That profound trust in the divine made his grandmother a great believer. One of her wishes was that her grandson should become a priest. Santiago boarded at a Passionist school28 in the town of Cameri, in the province of Novara, in the Piedmont region.29

Santiago studied at this school from the age of nine to fourteen. Life in this place and at that time was very austere and ascetic. He wore a habit cut from a cloth so rough that when he walked it hurt his legs and formed calluses on them.30 In this place in his early teenage years, Don Santiago discovered the contemplative life and an aspect of ascetic-mysticism.