Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Serie: 16Lives

- Sprache: Englisch

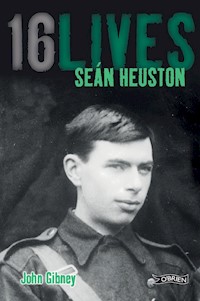

Seán Heuston was an Irish rebel and member of Fianna Éireann who took part in the Easter Rising of 1916. With The Volunteers, he held the Mendicity Institute on the River Liffey for over two days. He was executed by firing squad on May 8 in Kilmainham Jail. This book, part of the '16 lives' series, is a fascinating and moving account of his life leading up to and during these events. It follows his life, from his birth in Dublin, to his time as a railway clerk in Limerick. Finally it outlines his move back to Dublin, his joining The Volunteers, the Easter Rising, his imprisonment and execution. This book is a fascinating and moving insight into a man who sacrificed his life for his country.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 263

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The16LIVESSeries

JAMES CONNOLLYLorcan Collins

MICHAEL MALLINBrian Hughes

JOSEPH PLUNKETTHonor O Brolchain

EDWARD DALYHelen Litton

SEÁN HEUSTONJohn Gibney

ROGER CASEMENTAngus Mitchell

SEÁN MACDIARMADABrian Feeney

ÉAMONN CEANNTMary Gallagher

JOHN MACBRIDEWilliam Henry

WILLIE PEARSERoisín Ní Ghairbhí

THOMAS MACDONAGHT Ryle Dwyer

THOMAS CLARKEHelen Litton

THOMAS KENTMeda Ryan

CON COLBERTJohn O’Callaghan

MICHAEL O’HANRAHANConor Kostick

PATRICK PEARSERuán O’Donnell

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are a number of people I would like to thank for their assistance with this biography. Lorcan Collins was open to my willingness to tackle Heuston, and both he and Ruán O’Donnell have helped to keep the project on track. Edward Madigan gave me the benefit of his expertise on a number of occasions. I would like to thank the following individuals for generously providing me with leads, sources, and suggestions: Niall Bergin, David Kilmartin, Jim Langton, Damien Lawlor, Des Long, Shane Mac Thomais, Eamon Murphy, Andrias Ó Cathasaigh, Brian Ó Conchubhair, and Jim Stephenson. I would also like to thank Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc for permitting me to consult the late Donnchadh Ó Shea’s unpublished manuscript ‘Na Fianna Eireann, 1909-1975’. I naturally wish to thank the staff of the various archives and libraries in which I worked, especially Anne-Marie Ryan, formerly of Kilmainham Gaol; Brother Patrick Brogan of the Allen Library; and Peter Rigney of the Irish Railway Record Society Archives. At O’Brien Press Helen Carr has been an exemplary editor, and the text has benefited enormously from her scrutiny. Finally, I wish to thank my parents, Joan and Charlie, and Liza Costello for their encouragement and patience.

16LIVESTimeline

1845–51. The Great Hunger in Ireland. One million people die and over the next decades millions more emigrate.

1858, March 17. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, are formed with the express intention of overthrowing British rule in Ireland by whatever means necessary.

1867, February and March. Fenian Uprising.

1870, May. Home Rule movement, founded by Isaac Butt, who had previously campaigned for amnesty for Fenian prisoners

1879–81. The Land War. Violent agrarian agitation against English landlords.

1884, November 1. The Gaelic Athletic Association founded – immediately infiltrated by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

1893, July 31. Gaelic League founded by Douglas Hyde and Eoin MacNeill. The Gaelic Revival, a period of Irish Nationalism, pride in the language, history, culture and sport.

1900, September.Cumann na nGaedheal (Irish Council) founded by Arthur Griffith.

1905–07.Cumann na nGaedheal, the Dungannon Clubs and the National Council are amalgamated to form Sinn Féin (We Ourselves).

1909, August. Countess Markievicz and Bulmer Hobson organise nationalist youths into Na Fianna Éireann (Warriors of Ireland) a kind of boy scout brigade.

1912, April. Asquith introduces the Third Home Rule Bill to the British Parliament. Passed by the Commons and rejected by the Lords, the Bill would have to become law due to the Parliament Act. Home Rule expected to be introduced for Ireland by autumn 1914.

1913, January. Sir Edward Carson and James Craig set up Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) with the intention of defending Ulster against Home Rule.

1913. Jim Larkin, founder of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) calls for a workers’ strike for better pay and conditions.

1913, August 31. Jim Larkin speaks at a banned rally on Sackville Street; Bloody Sunday.

1913, November 23. James Connolly, Jack White and Jim Larkin establish the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) in order to protect strikers.

1913, November 25. The Irish Volunteers founded in Dublin to ‘secure the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland’.

1914, March 20. Resignations of British officers force British government not to use British army to enforce Home Rule, an event known as the ‘Curragh Mutiny’.

1914, April 2. In Dublin, Agnes O’Farrelly, Mary MacSwiney, Countess Markievicz and others establish Cumann na mBan as a women’s volunteer force dedicated to establishing Irish freedom and assisting the Irish Volunteers.

1914, April 24. A shipment of 35,000 rifles and five million rounds of ammunition is landed at Larne for the UVF.

1914, July 26. Irish Volunteers unload a shipment of 900 rifles and 45,000 rounds of ammunition shipped from Germany aboard Erskine Childers’ yacht, the Asgard. British troops fire on crowd on Bachelors Walk, Dublin. Three citizens are killed.

1914, August 4. Britain declares war on Germany. Home Rule for Ireland shelved for the duration of the First World War.

1914, September 9. Meeting held at Gaelic League headquarters between IRB and other extreme republicans. Initial decision made to stage an uprising while Britain is at war.

1914, September. 170,000 leave the Volunteers and form the National Volunteers or Redmondites. Only 11,000 remain as the Irish Volunteers under Eóin MacNeill.

1915, May–September. Military Council of the IRB is formed.

1915, August 1. Pearse gives fiery oration at the funeral of Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa.

1916, January 19–22. James Connolly joined the IRB Military Council, thus ensuring that the ICA shall be involved in the Rising. Rising date confirmed for Easter.

1916, April 20, 4.15pm.The Aud arrives at Tralee Bay, laden with 20,000 German rifles for the Rising. Captain Karl Spindler waits in vain for a signal from shore.

1916, April 21, 2.15am. Roger Casement and his two companions go ashore from U-19 and land on Banna Strand. Casement is arrested at McKenna’s Fort.

6.30pm.The Aud is captured by the British navy and forced to sail towards Cork Harbour.

22 April, 9.30am.The Aud is scuttled by her captain off Daunt’s Rock.

10pm. Eóin MacNeill as chief-of-staff of the Irish Volunteers issues the countermanding order in Dublin to try to stop the Rising.

1916, April 23, 9am, Easter Sunday. The Military Council meets to discuss the situation, considering MacNeill has placed an advertisement in a Sunday newspaper halting all Volunteer operations. The Rising is put on hold for twenty-four hours. Hundreds of copies of The Proclamation of the Republic are printed in Liberty Hall.

1916, April 24, 12 noon, Easter Monday. The Rising begins in Dublin.

16LIVESMAP

16LIVES-Series Introduction

This book is part of a series called 16 LIVES, conceived with the objective of recording for posterity the lives of the sixteen men who were executed after the 1916 Easter Rising. Who were these people and what drove them to commit themselves to violent revolution?

The rank and file as well as the leadership were all from diverse backgrounds. Some were privileged and some had no material wealth. Some were highly educated writers, poets or teachers and others had little formal schooling. Their common desire, to set Ireland on the road to national freedom, united them under the one banner of the army of the Irish Republic. They occupied key buildings in Dublin and around Ireland for one week before they were forced to surrender. The leaders were singled out for harsh treatment and all sixteen men were executed for their role in the Rising.

Meticulously researched yet written in an accessible fashion, the 16 LIVES biographies can be read as individual volumes but together they make a highly collectible series.

Lorcan Collins & Dr Ruán O’Donnell,

16 Lives Series Editors

CONTENTS

Title Page

Acknowledgements

16LIVESMAP

Conventions

Introduction

1 Heuston’s Dublin, 1891-1911

2 Heuston’s Ireland

3 Heuston and Na Fianna

4 Heuston’s Dublin, 1913-1916

5 The Prelude to the Rising

6 The Mendicity Institution

7 Heuston’s Fort

8 Capture and Courtmartial

9 From Sentence to Execution

10 Doomed Youth?

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Bibliography

Notes

Index

Plates

About the Author

Copyright

A note on conventions:

For the sake of clarity, I have adopted a number of conventions in the text and appendices. Differing spellings have been standardised, with the most common form preferred throughout; for example, ‘Seán’ rather than ‘Seaghán’, etc. However, as Heuston’s family usually referred to him as ‘Jack’, I have retained this usage in quotations wherever it was used by those closest to him. In quotations, I have silently modernised and standardised punctuation and grammar, and I have indicated interpolations and uncertain words in square brackets. With regards to place names, to avoid confusion I have preferred the terms currently in use, for example, ‘O’Connell Street’ rather than ‘Sackville Street’. The Mendicity Institution is often called the ‘Mendicity Institute’. This is incorrect: it was, and remains, the Mendicity Institution. The two terms are used interchangeably in quotations, and I have not standardised these, but I have opted for the term ‘institution’ in the text itself. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, all dialogue in the text has been taken verbatim from first-hand testimonies: it is reproduced as it was recorded.

Introduction

Seán Heuston wasn’t always called Seán. He was baptised ‘John Joseph’, and to his siblings he was ‘Jack’. At some point in his short life he had learnt Irish; in 1901, at the age of ten, he had been the only member of his family to claim any knowledge of the language on the census of that year and some of Heuston’s acquaintances and colleagues in later life testified to his fluency. But the reason posterity recalls him by the Irish version of his name has more to do with the fact that Heuston fought in the Easter Rising of 1916, and especially with what he told his younger brother, Michael, when he wrote to him on the night of 7 May 1916:

I suppose you have been wondering why I did not communicate with you since Easter but the explanation is simple. I have been locked up by his Brittanic Majesty’s Government. They have just intimated to me that I am to be executed in the morning.1

Michael Heuston was, at this time, a novice in the Dominican Order, based in Tallaght Priory. His elder brother instructed him that:

If the rules of the Order allow it I want you to get permission at once and come in here to see me for the last time in this world. I feel quite prepared to go – thank God, but want you to get all the prayers you can said for me. You will probably be able to come in the motor car which takes out this note.2

Presumably he did so, because Michael Heuston, along with Fr Michael – later Cardinal – Browne, then Master of Novices at Tallaght, arrived in Kilmainham Gaol at around 9.40 pm. The guards took their names and after some confusion about Browne’s status – the guards were initially unwilling to let in any priests apart from the official chaplains – they were brought in to see the prisoner they had come to visit.3 Michael Heuston later wrote an account of his visit to Kilmainham and of his last conversation with his older brother. It was intended for their sister Mary, who was a nun in Galway, and it recorded their conversation in exceptional, verbatim detail. It is unusual to have an account like this and we are lucky to have it. Along with the details of the conversation, Michael also recorded the circumstances in which it took place.

Two soldiers – ‘with candles’ escorted the two clerics ‘down a sloping passage into a covered courtyard with the cell’ – apparently number thirteen – to his left. Michael Heuston noticed a gas burner located in a hole in the wall; it was not lit. Upon entering the dim cell, ‘Jack’ – Michael never referred to his older sibling as ‘Seán’ – ‘came forward to meet me. He had an overcoat on but no ordinary coat, and I thought an old, grey waistcoat, but Duckie’ – their sister, Teresa – ‘says he had his own brown one, though the overcoat was not his own. He had an old, dirty-looking silk-looking handkerchief tied round his neck. He had no collar. He was unshaven, drawn, and dreadfully troubled looking. There was a little blood on his left cheek.’

The cell itself was quite small and inevitably spartan,

about fifteen feet long by six feet broad at the door, widening to nine or ten feet at the end, and about ten feet high. There was a barred window some two feet square high up in the end wall. The walls were whitewashed, the floor was of boards running lengthwise. On the left of the door on entering was a place with tins for food. Then a small, new wooden table with writing materials, and a stool. On the right was a shelf about five feet from the ground, with a crust with the soft part eaten out on it. There was a grey cap on it, but it was not Jack’s own. There was nothing in the nature of a bed except a roll of blankets near the table.

The soldiers remained to guard the brothers: one stayed at the door, while the other entered the cell. ‘Jack came over to me and shook hands with me. He had his rosary in his hand. He looked at me a fair while before he spoke. He spoke draggingly and in a dazed manner.’ One of the soldiers assured the brothers that, ‘You needn’t mind us. We’ll make no use of anything you say.’ Michael was surprised to find that the soldiers did not insist on their conversation being spoken aloud, as his older brother put an arm around his neck.

‘Well, Michael, how are you? Don’t cry now,’ said Seán. ‘So I didn’t come out to you on Easter Monday. I thought we would have. We were to have a camp at Rathfarnham, but then this thing came off. Were you able to come all right? I thought it might have been against the rules. Did the motor-car go for you?’

Michael assured Seán that ‘there was no difficulty about coming, and that the brothers were saying the Rosary for him.’ Their last conversation continued in an almost everyday manner for some time.

‘What time did you get the letter?’ said Seán.

‘About nine o’clock,’ was the reply.

‘So it must have gone immediately.’

‘When did you hear?’

‘Just tonight. I got the paper – “confirmed by J.G. Maxwell”. I wrote to you immediately. I was afraid you might not get it in time, that you might be in bed. I have also written for Mother and Teasie and Duckie’; these latter two were his aunt and sister, both named Teresa. ‘I wrote, too, to Mary’ – their eldest sister – ‘and some others, Mr Walsh, Dalton, Tierney of Limerick.’ Seán pointed out the letters on the table to Michael.

‘I was writing while waiting for you. Did anyone come with you?’

‘Yes, Fr Browne.’

‘Where is he? Did he not come in?’

‘They would not let him in.’

‘What?’ Heuston began to remonstrate with one of his guards. ‘Would they not let Fr Browne in?’

‘Ah, now,’ said Michael, ‘Don’t mind, it’s all right I suppose they couldn’t. He’ll say mass for you in the morning and so will some of the other priests.’

At this point Browne joined the Heustons in the cell, having been delayed by the guards. But, he assured them, ‘the corporal was a decent fellow, willing to strain a point.’ Seán thanked him for coming and, as Michael Heuston recalled:

Fr Michael said something to him about meeting him before when visiting me in Tallaght. He said something to him about offering his death as his purgatory and he said he would. Jack asked Fr Michael could he speak alone with him for a few minutes.

But this could pose difficulties:

Fr Michael was afraid he might want to go to confession to him and that, if he did, the prison authorities might not let the other priests [in] to him later on, saying that he had already been attended to, so he asked him would he not have the other priest later and Jack said it was alright so. Fr Michael had some office to say and he left us alone while he said it.

Browne, in his own words, ‘withdrew a little to allow them’ – the Heuston brothers – ‘to be alone together.’4 As he did so he heard weeping from the cell next door – number eighteen, in which Michael Mallin of the Irish Citizen Army was imprisoned – and Browne went to offer such consolation as he could to Mallin and his family.

Back in Heuston’s cell, the ‘soldier who had come into the cell had moved back to the door.’

‘Can you stay?’ asked Seán.

‘I can stay all night if we are let,’ replied Michael. ‘What time will it be?’

‘It’ was his brother’s impending execution.

‘A quarter to four.’

‘They are giving you a soldier’s death anyhow. It is better than hanging.’

‘Yes, they are giving us a soldier’s death. I am quite ready to go. I am dying for Ireland. We thought we would have succeeded. Perhaps we won’t fail next time. I was at confession and communion at Easter too. The chaplain will bring us communion at half twelve tonight, and Fr Aloysius will come at two o’clock.’ ‘Fr Aloysius’ was the Capuchin Fr Albert; Heuston had confused the names.

‘You had mass then today?’

‘Yes, but not last Sunday when we were in Arbour Hill.’

‘How many are there?’

‘There is [Michael] Mallin, a Citizen Army man, and Kent [Éamonn Ceannt].’

‘How did they choose out you?’

‘I don’t know. We killed a lot of soldiers and two officers. They found Connolly’s orders on me, but I think they got something else against me too.’

‘You were in the Mendicity Institute,’ asked Michael. ‘What is it?’

‘It’s a place over on the South Quays – the quay before Guinness. How did you know I was there?’

‘Fr Browne was in looking for you last Tuesday, but could find nothing about you. Mother told him that you were in the Mendicity Institute. On Wednesday we heard you were in prison. Yesterday we heard you were wounded in hospital and Fr Browne was talking with me today of coming in tomorrow to try and see you, as he thought it would be easy for him if you were wounded. Were you wounded at all?’

‘No.’

‘Someone said she saw you at Stoneybatter on Easter Tuesday. Were you there?’

‘No. It must have been someone else she saw.’

‘Had you much fighting at the Mendicity Institute?’

‘No, not much. We were not there so much to fight as to keep the troops from going down the quay into the city – the Four Courts, etc. We kept them back for two full days. Not one could pass down while we were there …’

The conversation continued for some time, but Heuston had come to the reason why he now found himself imprisoned. And, just as he had been told earlier that evening, in the early hours of the next morning, 8 May 1916, Seán Heuston was executed by a British firing squad in the grounds of Kilmainham Gaol. On 4 May he had been tried by court martial in Richmond Barracks in Inchicore and was found guilty of participating in ‘an armed rebellion and in the waging of war against his Majesty the King, such act being prejudicial to the Defence of the Realm and being committed with the intention and for the purpose of assisting the enemy.’5 The United Kingdom of which Ireland was a part was, after all, at war.

This was the general charge levelled at Heuston. It arose from his specific activities in the events of the Easter Rising, as the man in charge of an outpost whose size belied its significance. The Mendicity Institution was a charity based on the south quays of the River Liffey that had been providing food and sustenance to the poor of Dublin’s inner city for almost a century. Based in an old townhouse, it had an importance to the insurgents as it overlooked a natural entry point into Dublin city centre; as troops began to enter the city centre, Heuston’s small garrison began to exchange fire with them. The British endured heavy casualties at another key junction on Dublin’s southside – Mount Street Bridge – but while the fighting around the Mendicity was nowhere near as bloody as there, the street battle that Heuston and his men became embroiled in was, in theory, of a similar significance.

Michael Heuston later tried to understand what his brother had got involved in. Some days after Seán’s execution – ‘the Thursday following’ – Michael Heuston went over to the Mendicity Institution, ‘but could find no trace of anything except three or four bullet marks on the walls outside and the windows all broken, not by rifle fire, but as it were by the Volunteers themselves.’6 He returned to the Mendicity the following Tuesday ‘and got into it. The people were put out on Easter Monday by the Volunteers. The soldiers they shot down were diagonally across the river at the other side and so were at a considerable distance. They must have been good marksmen to single out the officers and kill them at such a distance’, though the precise details remained obscure; ‘it is, of course, quite evident that Jack’s pistols could not have carried across the river.’ Seán Heuston, while talking to his brother, had mused on the various reports and rumours he had heard about the efficiency (or otherwise) of the British troops involved in the fighting across the city, but it would seem that those who had been fighting around the Mendicity had been good at their job.

‘The soldiers then surrounded the Institute,’ wrote Michael, ‘cutting off the means of retreat.’ Michael tried to make sense of the scene as he was shown around the building, presumably by a caretaker:

The man who showed me round told me he walked up and down several times and he saw not a single Volunteer at the windows. The soldiers here seem to have been good shots, for I saw few traces on the outside, but the inside was full of holes from the bullets. The direction of the holes showed that shots had come from above and below them on the quays, and I think some even from the other side of the river, possibly from the roofs of the houses, for some few holes were low down – lower even than the window sills. There were two or three holes right through the floor of the first storey into the ground storey. At one place half a door was shot away and a hole about eighteen by nine inches made right through the floor. This was where one of the Volunteers was badly wounded. The man said the place was full of blood here. These were, of course, the work of the grenades. He said to throw these, the soldiers came round quite close under cover of some low walls. When they succeeded in getting them in, the Volunteers held out no time [sic]. One of the Volunteers took a gold pin away. This was found on him at Arbour Hill, I hope this is not true. Some of the soldiers quietly removed £9 or £10 of his. He said, including broken furniture etc, there was about £60 [worth of] damage done.

It would be impossible to recreate Michael Heuston’s pilgrimage to survey the aftermath of the fighting today, for the original building is gone (though it is sobering to think that almost a century after Irish independence, the Mendicity Institution continues to feed Dublin’s poor from another building on the same site, just as it had done for over a century beforehand). The significance of the Easter Rising to the struggle for independence is unlikely to be disputed; what this short book is concerned with is the figure whose role in the Rising is inextricably linked to the Mendicity Institution. Seán Heuston (to use the most common version of his name) was born in Dublin’s inner city slums and was one of the youngest (along with Edward Daly) of those executed in the aftermath of the Rising; a fact that made his execution all the more controversial. Every day Heuston’s surname plays a part in thousands of journeys through the train station that bears it. This biography is intended to flesh out the life of an individual who, all too often, is simply listed as one of W.B. Yeats’ sixteen dead men.

What can we know of the life he led beforehand?

Chapter 1:

Heuston’s Dublin

1891-1911

Seán Heuston was born John Joseph Heuston on 21 February 1891 at 24 Lower Gloucester Street (now Seán MacDermott Street), the son of John Heuston, a clerk, and his wife Maria (née McDonald).7 John Heuston – Seán’s father – was born on 10 August 1865 at 65 Great Strand Street, the son of John Heuston, a porter, and his wife Mary Anne (née Clarke). Heuston’s mother, Maria was born on 29 December 1867 at 61 Marlborough Street, the daughter of Michael McDonnell, a bedroom porter, and his wife Mary (née McGrath). The civil authorities seem to have confused the surname of Heuston’s mother; even on the birth certificate of her youngest child, Michael, born in 1897, her maiden name was given as ‘McDonnell’. But such glitches were not unknown; it seems likely that this was indeed the Maria McDonald who had been baptised in the Pro-Cathedral(also on Marlborough Street) on 31 December 1866 and who married John Heuston in the same venue on 22 January 1888.8 Seán Heuston’s roots lay in Dublin’s north inner city.

Of the sixteen men executed after the Easter Rising, six – Heuston, Roger Casement, Michael Mallin, the Pearse brothers and Joseph Mary Plunkett – were from Dublin. With the possible exception of Mallin, Heuston came from the humblest background of them all. His father, John, was a clerk, though the precise details of his job and his background remain obscure, as do many of the details of Heuston’s early life. Clerical jobs in the capital were reasonably meritocratic, insofar as the closed shops operating in other professions and trades rarely applied to them. By the end of the nineteenth-century there was a slow but sure increase in the numbers of clerks from working-class backgrounds; a small indicator that social mobility wasn’t unheard of in Victorian Dublin. But the key criterion for clerical jobs was an education. This meant that they were effectively restricted to families who could afford to keep a child in education, and this placed them beyond the reach of the vast ranks of the unskilled labouring poor.9 Heuston’s father was lucky in one sense, but the address at which the family lived in 1891 points very strongly towards the world from which they came and from which, presumably, they were trying to escape.

At the time of their marriage Heuston’s father lived at 12 North James’s Street and his mother at 34 Jervis Street. They began their family at 24 Gloucester Street, on the fringes of the vast Gardiner estate north of the River Liffey. This had been developed by the Gardiner family from the 1720s onwards and its centrepiece was Sackville Street and Gardiner’s Mall, both of which would later be merged into Sackville – O’Connell – Street. The estate was one of the most prestigious residential areas of what was, in the eighteenth-century, a city dominated by the Protestant aristocracy known to history as the ‘ascendancy’.10 Dublin had been a centre of administration, education, the judicial system and trade for centuries; its reworking as a ‘Protestant’ capital city during the eighteenth-century went hand in hand with an extraordinary growth. Many of its public buildings and much of the streetscape that its inhabitants were still familiar with in the early twentieth-century dated from that era; by circa 1800 Dublin’s population had tripled within a century to approximately 182,000. Even aside from the presence of the aristocracy (who accounted for a large chunk of the city’s economy), eighteenth-century Dublin had become a significant manufacturing centre and a major distribution point for imported goods. Its cultural and political influence was unmatched on the island and the description of Dublin as the apocryphal ‘second city’ of the British Empire makes a great deal of sense in relation to the eighteenth-century. Yet the same cannot be said of the nineteenth.

Dublin has presented a number of faces to the world, but two of the best known go hand in hand, as the splendour of the eighteenth century gave way to the squalor of the nineteenth. There were various reasons for this transition, but the symbolic dividing line was usually taken to be the Act of Union of 1800. The formal integration of the Irish parliament with its British counterpart meant that Ireland’s ruling elites began to leapfrog Dublin en route to London, and the aristocracy for whom much of the city was remodelled slowly but surely abandoned it. This was not the only reason for Dublin’s decline, but it was a very visible mark of it. Take, for example, Aldborough House, located a few hundred yards from Heuston’s eventual birthplace in the north of the city. Completed in 1799 for John Stratford, second earl of Aldborough (who died in 1801), it was apparently meant to rival Leinster House on the southern side of the River Liffey, but ironically, was the last aristocratic mansion to be built anywhere in the city. It later became a barracks, which helped to sustain the large and notorious red light district that sprang up in the streets around Heuston’s birthplace: ‘Monto’.

The Act of Union was indeed a landmark in the history of both Ireland and its capital, with Dublin now becoming a regional capital within the new United Kingdom. Aldborough House may have been the last of its kind, but other building projects continued after 1800 (though not on an eighteenth-century scale): the GPO (1818), King’s Inns (1820), the commissioners for Education on Marlborough Street (1835-61) and the prisons at Arbour Hill (1848) and Mountjoy (1850), to name a few that formed a backdrop to Heuston’s life. The city that he grew up in had not come to a shuddering halt at the turn of the nineteenth-century: Dublin continued to grow after the union. But the rate at which it did so was much reduced and the size of its population gives an indication of its decline: in 1891, the year of Heuston’s birth, the population was only 245,000. Even aside from the loss of the aristocracy and the parliament, Dublin embarked upon a downward spiral in the decades after 1800, as its traditional industries (such as textile manufacturing) were whittled away. Within the newly-expanded United Kingdom, Dublin’s primary function was as a transit point for the export of food and people and the importation of British goods: a perpetual motion driven by the imperatives of Britain’s industrial centres. The vast bulk of its trade was with the rest of the UK rather than the rest of the world; the docks that lay so close to Heuston’s place of birth were in no way comparable to the great docklands of Britain. Dublin was not an industrial city; other than food processing it lacked labour-intensive industries, and was in no position to compete with other major UK cities like Birmingham, Glasgow, Liverpool or Manchester.

There were, however, some shards of light amidst the gloom. By the end of the nineteenth century Dublin had