9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

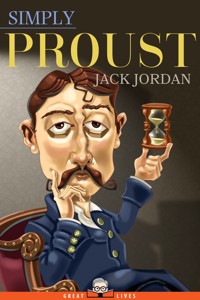

- Herausgeber: Simply Charly

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Serie: Great Lives

- Sprache: Englisch

“Simply Proust pulls off with ease the arduous task of making Marcel Proust’s masterwork accessible, without sacrificing none of the complexity that makes it one of the most important novels of the 20th Century. To do this, Jack Jordan vividly paints vast the cultural, scientific, and philosophical background that fed In Search of Lost Time. Armed with this knowledge, both new and repeat readers are bound to gain fresh insights into the brilliance of Proust’s novel.”

—Hervé G. Picherit, Associate Professor of French, University of Texas at Austin

Marcel Proust (1871-1922) was born in Paris during a time of great social and political upheaval, a ferment that is dealt with extensively in his monumental work In Search of Lost Time. He was a sickly child and spent the earlier part of his short life pursuing a variety of sometimes frivolous activities, which led to his not being taken seriously as a writer. It was not until 1909, when he was 38 years old, that he began work on the groundbreaking novel for which he is known, a task that consumed the rest of his life.

In Simply Proust, Professor Jack Louis Jordan presents an incisive, yet thoroughly accessible, introduction to Proust’s landmark work, helping the reader to fully appreciate the scope of the author’s achievement, as well as the fascinating process that underlay its creation. Emphasizing the fundamental role of psychology and the unconscious, Jordan shows how Proust’s methodology and our understanding of his novel are connected, and how this makes for a unique and endlessly revealing literary experience.

At once philosophical, psychological, and deeply human, Simply Proust offers an invaluable entry point into a masterpiece of world literature and takes the measure of the flawed and brilliant man who transformed the material of his life into a transcendent work of art.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 205

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

SIMPLY PROUST

GREAT LIVES

JACK JORDAN

CONTENTS

Other Great Lives

Series Editor's Foreword

Preface

À la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time)

1. Marcel Proust’s Early Days

2. Out and About

3. In Search of Lost Time

4. Final Years

5. The Narrator: Travels in the Space-Time Continuum

6. A Search for Certainty

7. Transportation

8. Proust and the Human Sciences

9. Proust the Naturalist

10. Three Types of Observation

11. The Reader: Riding the Proust Wave

Sources

Suggested Reading

About the Author

A Word from the Publisher

Simply Proust

Copyright © 2020 by Jack Jordan

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without prior written permission from the author, except for brief quotations used in reviews or critical articles.

For permissions or inquiries, contact: [email protected]

ISBN (Paperback): 978-1-943657-20-9

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-943657-44-5

First Edition: 2023 Printed in the United States of America

Visit us online!

OTHER GREAT LIVES

Simply Austen

Simply Beckett

Simply Beethoven

Simply Chekhov

Simply Chinggis

Simply Chomsky

Simply Chopin

Simply Darwin

Simply Descartes

Simply Dickens

Simply Dirac

Simply Eliot

Simply Faulkner

Simply Gödel

Simply Hegel

Simply Hitchcock

Simply Joyce

Simply Keynes

Simply Nabokov

Simply Napoleon

Simply Nietzsche

Simply Riemann

Simply Sartre

Simply Stravinsky

Simply Tolstoy

Simply Turing

Simply Wittgenstein

PRAISE FOR SIMPLY PROUST

Simply Proust is an excellent introduction and guide to Proust’s fascinating life and his monumental work In Search of Lost Time. Themes such as love, jealousy, snobbery, voyeurism, and brothels, as well as characters in Proust’s novel, are treated in an engaging, entertaining manner. Jack Jordan’s book is a joy to read, full of interesting information, and is highly recommended.

CYNTHIA GAMBLE, HONORARY RESEARCH FELLOW, UNIVERSITY OF EXETER, UK

Simply Proust pulls off with ease the arduous task of making Marcel Proust’s masterwork accessible, sacrificing none of the complexity that makes it one of the most important novels of the 20th Century. To do this, Jack Jordan vividly paints the vast cultural, scientific, and philosophical background that fed In Search of Lost Time. Armed with this knowledge, both new and repeat readers are bound to gain fresh insights into the brilliance of Proust’s novel.

HERVÉ G. PICHERIT, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF FRENCH, UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN

In this fast-paced book, Jack Jordan condenses a lifetime of teaching and research on Proust into a lively and accessible format. Jordan introduces us to Proust, his family, and his friends, all the while taking care to explain and respect Proust’s own thoughts on the gap between life and work, between the social self and the hidden, creative self. Jordan inspires us to read, or reread, Proust’s novel, inviting us to “Take those long sentences and paragraphs as a surfer would big waves.” Jordan brings out, in particular, the modernity of Proust’s novel: its love of speed, motion, and technology; its engagement with the latest scientific developments in physics, evolution, and psychology.

JENNIFER RUSHWORTH, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR IN FRENCH AND COMPARATIVE LITERATURE, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON, UK

Professor Jack Jordan’s richly contextualized introduction to Proust revisits the intricate and quasi-mythologized relationship between the writer’s life and work in surprisingly lucid ways. From biographical facts through contemporaneous science and sociology to novelistic interpretations, these 11 highly accessible and introspective chapters enthrall the reader to embark on an exciting journey through the Proustian ‘space-time continuum.’ Simply Proust is written with considerable erudition, witticism, and poise, and is also sprinkled with practical tips for a literary amateur’s budding Proust pilgrimage.

SHUANGYI LI, RESEARCH FELLOW IN FRENCH AND COMPARATIVE LITERATURE, CENTRE FOR LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE, LUND UNIVERSITY, SWEDEN

Jack Jordan’s Simply Proust is a perfect introduction to In Search of Lost Time, one of the greatest novels of the 20th century, as well as to its author, Marcel Proust. After an excellent biographical section that connects Proust’s life to his work, it presents and analyzes the multiple facets of the novel in a compact and accessible fashion. Simply Proust especially emphasizes the French novelist’s modern outlook and shows how his view of the world is closely linked to the scientific discoveries of his time. Yet, it also demonstrates how In Search of Lost Time is a fascinating voyage of self-discovery for today’s reader.

PASCAL IFRI, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF OF BULLETIN MARCEL PROUST & PROFESSOR OF FRENCH, BROWN UNIVERSITY

Although simplicity is not usually associated with In Search of Lost Time, Professor Jack Jordan does a remarkable job of rendering Marcel Proust’s masterpiece accessible. The engaging biography section describes how Proust drew on real-life figures and on his own complex emotions to capture an entire era so vividly that readers feel they have lived there themselves. A thematic section provides a catalog of the perspectives, techniques, and patterns Proust uses to weave the 3000 pages of his seven novels into a brilliant whole capable of changing our views on our own lives. A deeply informed and highly readable introduction.

CATHERINE LE GOUIS, PROFESSOR OF FRENCH, MOUNT HOLYOKE COLLEGE

Simply Proust provides a wonderfully engaging look not only at the life and work of Marcel Proust, but also at the convoluted relationship that exists between them. Demonstrating wide-ranging knowledge of Proust’s monumental masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time, and of the cultural, personal, and social contexts in which it was written, Jack Jordan brings out the astonishing narrative richness, variability—and sheer strangeness—of Proust’s work, moving effortlessly between discussions of—among other things—the significance of new technologies (including planes, trains, and automobiles) in the novel, of the relationship between Einstein’s theories of relativity and Proust’s own investigations in the space-time continuum, of Proust’s attempts to describe the workings of the unconscious, and of the relationship between the experience of reading Proustand of hypnotism. Written with enviable clarity and humor, Simply Proust is also, on a more light-hearted note, a rich source of funny anecdotes from Proust’s life, including details of his addiction to ice cream.

THOMAS BALDWIN, READER IN FRENCH AND CO-DIRECTOR OF THE CENTRE FOR MODERN EUROPEAN LITERATURE, UNIVERSITY OF KENT

SERIES EDITOR'S FOREWORD

Simply Charly’s Great Lives series offers concise yet deeply insightful introductions to the world’s most influential thinkers and creators—scientists, artists, writers, economists, and other extraordinary figures whose ideas and achievements continue to shape our world.

Each book opens a window into the life and mind of its subject: their work, their inspirations, the pivotal moments that defined them, and the obstacles they overcame along the way. You’ll also find glimpses of their lesser-known sides—the quirks, contradictions, and private battles that make geniuses feel unmistakably human.

Written by leading scholars and experts who have spent years studying their subjects, these volumes move far beyond the familiar timeline of “greatest hits.” They dive deep into the thought processes, struggles, and turning points that propelled these figures toward their most enduring contributions.

The Great Lives series brings clarity and depth to complex lives, transforming historical icons into vivid, relatable individuals whose ambitions and doubts mirror our own.

Ultimately, we hope that these books do more than inform—that they inspire. Because the best stories of extraordinary lives don’t just teach us about the past; they remind us what’s possible in our own.

Charles Carlini

New York City

PREFACE

When someone asks if you have read Marcel Proust (1871–1922), the question usually refers to his 3,000-page novel, In Search of Lost Time. Though a prolific writer in numerous genres, without the publication of his masterpiece, it is unlikely that his name would have become as well-known as it has. Some individuals who have read In Search of Lost Time consider it to be the greatest novel ever written. Others are more limited in their praise, describing it as the greatest novel of the 20th century or in the French language. Whatever the case may be, it is rare, if not unique to Proust, that a writer has devoted his entire life to creating one novel whose vision reaches from the details of his own life and times to a metaphorical description of the essence of man.

For many, Proust’s name is also often synonymous with “difficult to understand.” The most obvious reasons for this are the size of the novel and the (in)famous length of some of his sentences. Take those long sentences and paragraphs as a surfer would big waves. Enjoy the ride as long as you can, then have fun falling into what a British academic Malcolm Bowie called the “large tidal movements” that make up “Proust’s gritty, breezy, and salty book.” Let yourself go and enjoy letting the currents take you where you have not been before.

Since Proust first tried to publish his novel, some readers have had difficulty understanding the lack of an obvious chronological development in characters and plot. Some have found his descriptions of the very ordinary experiences and things that make up daily life to be boring. Swann’s Way, the first of the seven volumes that make up In Search of Lost Time, was rejected several times, most famously by André Gide, editor of La Nouvelle Revue Française, the leading French publisher at the time. He later said it was the biggest mistake of his career. Alfred Humblot, the general editor of Ollendorf, Proust’s second choice, also rejected it.

“My dear friend,” Humblot wrote. “I might be dead from the neck up, but rack my brains as I may, I fail to understand why a man needs thirty pages to describe how he tosses and turns in his bed before falling asleep.”

His reaction was not uncommon. But, while seeing what lies on the surface in Proust’s novel, he did not perceive what lies below the mundane, ordinary experiences shared by everyone. The times spent falling asleep and waking up are precious parts of the territory that make up the novel’s quest. They are the bridges between each person’s conscious and unconscious states and can ultimately lead one to the underlying meaning of his novel, which Proust described as a “series of novels of the Unconscious.”

Proust finally had to publish Swann’s Way himself. Despite its slow start, the praise for this innovative novel started pouring in. The numerous translations that are still being done attest to this and the rest of In Search of Lost Time’s continuing, universal appeal; properly presented, these aspects are part of what can make the novel more appealing and better understood by modern readers.

Though Proust’s novel reflects today’s modern, relativistic worldview so well, it is also rich in the particulars of his time. While not an autobiography, this masterpiece is profoundly rooted in his life. He used what he learned from his family, his friends, himself, and the world he lived in and observed with the passion of an artist and the detached perspective of a scientist to create the world of his novel. He enthusiastically embraced, observed, analyzed, and wrote about who and what he experienced—from the smallest details to the most general laws he saw governing man and the world. The end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century were a period of great change in science, technology, psychology, and art. Man’s relationship to the world around him was being changed by the popular use of trains and the introduction of cars and planes; the increased speed changed his relationship to time and space. Distance was no longer fixed, time and space no longer absolutes.

The arts lie at the heart of Proust’s novel, but the sciences provide the tools needed to arrive at the end of the search. Chief among them is psychology. It provided a scientific methodology to reach the essence of “self” and the terminology to express it, taking the search beyond a vague, romanticized notion of man’s identity. As this book will show, it also takes the search outside the novel and makes the reader a member of the quest. The results can be exciting and unexpected.

As with Proust’s masterpiece, there are aspects of his life that have been associated with his name. They range from his childhood sicknesses, privileged existence, close relationship with his mother, and the French pastries called madeleines, to his cork-lined room, inversion of night and day, and a snobbish, sedentary, and reclusive existence when he was an adult. Some of these deserve further explanation, and others correction. Both will follow.

In Search of Lost Time is the story of the Narrator’s search for a vocation. This also describes a long quest in Proust’s own life, which served as a narrative for his novel. Until he found this narrative, his voice, and what would be the essential experience of involuntary memory, Proust (and the Narrator) could not start his novel and did not truly consider himself a writer. Without the experience of the special pleasure brought about by a chance encounter with an object in the world that would ultimately provide the foundation for his “immense edifice of memory,” the quest both for a vocation and a vision that would eventually result in this masterpiece was a dilettante’s dream.

Though memory lies at the heart of Proust’s novel, it is only in a small part the sentimental journey backward in time that is suggested by the former English translation of the title, Remembrance of Things Past. With the current, more literal title, In Search of Lost Time, not only is the essential element of Time introduced, but it is also paired with Lost, suggesting multiple meanings. Taken as “wasted,” “lost time” can mean the years the Narrator (and Proust) spent going to the many cultural and social events in Paris that include the periods known as the fin de siècle and the belle époque, and continue until after World War I. Some of these sorties included attending certain salons that permitted him to move about in society and to know aristocrats, writers, musicians, and other important social, political, and artistic individuals. He would then write articles and other small pieces for newspapers describing these people and events. Not only did the time that he was not spending on a serious work of literature concern Proust (and the Narrator), but also the reputation that he got for being a superficial chronicler of Parisian social life around the turn of the century would haunt him even after he started to publish his masterpiece. Anything that took him away from the confines of his room, where he could work on his novel, was time wasted. As it turned out, these activities gave him the substance for much of his novel and provided the reader with an excellent perspective on Proust’s life and times.

“Lost time” can also be understood as the temporal aspect of the extraordinary experience he had with the “special pleasure” that takes one outside the limits of time and space. This interpretation leads one to the heart of the Narrator’s (and Proust’s) quest: the search for the answer to the fundamental philosophical questions, “who am I?” and “what is the nature of the world?” It is the search for the essence of man, world, how either can be known, and how these discoveries can be expressed. The unified worldview that results is the philosophical foundation supporting the rich, complex structure of Proust’s novel. The paths that lead to this provide a fascinating look into the creative process and form a large and important part of this book.

This “special pleasure” is born from an experience of involuntary memory. In contrast to voluntary memory, it does not rely on rational efforts to retrieve lost memories. It cannot be forced. Through a chance sensory contact, a past feeling comes alive in the present, taking one out of the normal confines of time and space. Only afterward does intelligence play a role. This is one of the most fundamental of the many oppositions, or dualities, that pervade Proust’s novel. Other important oppositions include (but are not limited to): Swann’s Way, the Guermantes Way (geographic and social); habit, novelty; light, dark; night, day; clear, obscure; inward, outward; particular, general; micro, macro; enclosed, open; and tragic, comic. All will be shown to be either a synthesis or at least two essential sides of life and the world. Proust also arrived at the two essential parts of any knowledge: a subject to know and an object to be known. This simple opposition or duality (subject-object) lies at the heart of Proust’s philosophy and worldview.

The goal of Simply Proust is to introduce Proust’s unusual life and times and explore the thoughts that inspired him to create his novel. This book also intends to help understand the basic, symmetrical structure, as well as the simple elegance of this seemingly complex novel, and to provide a personal experience for the reader. While we can’t go into every particular detail that makes up Proust’s edifice, we can see certain patterns that develop from the smallest detail to the structure of the entire novel.

We will look at some of the most important of the Narrator’s experiences to see what patterns emerge within the repetitions and changes. These meaningful experiential dots will be connected at the end of the novel using the will, the tools of reason, and intelligence to deduce the essence of man and world, as well as the laws that govern them. By underlining whatever makes an impression, whether understood at the time, the reader may also create dots that, after being looked at from a later perspective, can also create a picture or mosaic that is unique and personal yet rooted in the novel. If a phrase or an idea keeps repeating in your mind, pay attention to it. If you would like to have a colorful perspective of the first few pages of the novel, mark each reference to light in one color and those to time in another. There will be lots of color reflected by these two essential aspects of Proust’s entire novel.

The layout of the chapters reflects the two essential relationships to the novel (Author–Novel–Reader). The chapter titled “Marcel Proust's Early Days” delves into his life and its relationship to In Search of Lost Time. His family, friends, and other sources are presented, along with other sources for the events, places, and ideas that occur in the novel.

Due to the important role the Narrator has regarding the author, the novel, and the reader, the discussion of the novel is divided into two parts: “The Narrator: Travels in the Space-Time Continuum” and “A Search for Certainty.” The ever-present question of identity continues to play a predominant role in the former. Is there one or several Narrators? Is there one core Self or several selves? What should he be called? How does the Narrator welcome the reader, including him or her in the quest? Through the Narrator’s experience of involuntary memory, a causal, positivistic universe is replaced by one based on a synchronistic, acausal worldview where the relationship between time, space, and identity is recreated. In “A Search for Certainty,” the major themes and features of the novel are presented in a way that reflects those of In Search of Lost Time. It is inductive, moving from the particular to the general, and it moves outward, from the bedroom to the stairs to the house itself. At the end of “Combray,” the first part of Swann’s Way, the “raised finger of the day” points the way out of the confines of the Narrator’s bedroom that will ultimately lead to the certainty that was lost in the darkness of the opening pages of the novel.

Another chapter looks at the essential role the reader plays in the Narrator’s quest, how he or she is included, what the role of the unconscious is, and what relevance this can have in one’s own life. Proust’s (and the Narrator’s) experiences with psychology are continued from the previous chapter, with an emphasis on the possible role hypnosis plays and how this can affect the reader’s experience.

Proust blurs the boundaries that separate the world of the novel from that of the author and from that of the reader. Despite his clear and often-stated opposition to looking at a piece of art (literary, pictorial, etc.) from the side of its creator and his emphasis on the importance of the relationship on the other side of the novel, from that of the reader, the boundary between Proust and the novel is also blurred. One of the means by which this is achieved is by using real historical figures and events alongside fictional characters. This particular mixture is one reason for the historical richness of Proust’s novel.

The novel is not short, which in itself limits its general appeal. However, just as it takes time to create a world, it takes time for a person to be transported into it. Ideally, it should be read at night, undisturbed by anyone or anything that might interfere with becoming part of the novel, like the Narrator who, on the first page, describes himself as falling asleep while reading, seemingly becoming the subject of the book. If you do not have the time to read the novel from beginning to end, try reading the first and last volumes together. Try not to let the novel’s reputation as being difficult bother you. Just read it and try to hang on because if you give it a chance, you may be in for a ride as rewarding as those taken by Aladdin on his magic carpet in The Arabian Nights.

Jack L. Jordan

Orange Beach, Alabama

À LA RECHERCHE DU TEMPS PERDU (IN SEARCH OF LOST TIME)

1913 Volume I: Du côté de chez Swann (Swann’s Way)

1918 Volume II: A l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs (Within a Budding Grove)

1920 Volume III: Le Côté de Guermantes (The Guermantes’ Way)

1921 Volume IV: Sodome et Gomorrhe (Sodom and Gomorrah)

1923 Volume V: La Prisonnière (The Captive)

1924 Volume VI: Albertine disparue (The Fugitive)

1927 Volume VII: Le Temps retrouvé (Time Regained)

The dates are those of the French versions. For the purpose of simplification, the volumes are summarized under their current titles.

MARCEL PROUST’S EARLY DAYS

Marcel Valentin Louis Eugène Georges Proust was born on July 10, 1871, in Auteuil, a suburb of Paris. His father, Adrien Proust, was born in 1834 in Illiers, a small town near Chartres, not far from Paris. His mother, Jeanne Clémence Weil, was born in 1849 in Paris. Both of his parents were from relatively wealthy families. His father was Catholic and his mother was Jewish, and even though Marcel and his brother Robert were raised Catholic, religion was not a dominant force in the family. When his parents were married, the Second Empire was ending, and the Third Republic was beginning. It was the start of new Constitutional Laws, establishing a regime based on parliamentary supremacy.

Even for the relatively wealthy, this was not an easy time, and the newlyweds had to survive the sieges and bombardments of the Prussians and then the insurrection of the Communards. The childhood sicknesses that plagued Marcel could be attributed to these circumstances. Later, when he was nine, he almost died from an asthma attack, the first of many to follow and which would have a profound effect on him for the rest of his life. One bright aspect of this illness was that he spent holidays at the beach in Normandy, where he could breathe easier thanks to the sea air. The time he spent there was good for his health, and the area would become a regular vacation destination. The town of Cabourg would become Proust’s inspiration for Balbec, the seaside resort featured in his book. His brother, Robert, who was born in 1873, did not suffer from Marcel’s ailments and became a doctor, like their father. Though they seem to have gotten along relatively well despite their differences and usual sibling rivalries, Proust’s Narrator does not have a brother.