4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

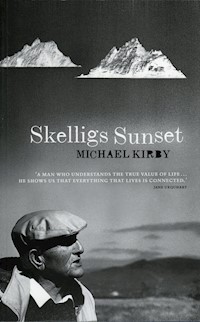

Skelligs Sunset, a posthumous volume of work in English by Michael Kirby, is the final part in his trilogy of memoir, storytelling and poetry begun with Skelligside (1990) and Skelligs Calling (2003). This remarkable writer, farmer-fisherman and painter was born in May 1906 and died in April 2005. Aside from a three-year sojourn in the United States where he worked on the railroads during the Great Depression, he spent his lifetime in County Kerry. He also wrote eight books in Irish under the name Micheal Ua Ciarmhaic, and from his eyrie in Ballinskelligs bore witness to a world that changed so radically, from the age of the transatlantic cable to the era of the Internet. His lyric poems evoke the sea, wind and landscape of south Iveragh in all its natural beauty. The memoirs, beginning with his schooldays and concluding in his garden, describe characters from fellow storyteller Sean O Conaill to Dan of the Roads, and record night hauls at sea, superstitions, wedding customs, games, pastimes and petty sessions in the Portmagee courts. Folklore and tall tales of courtship, fortune-seeking, gypsy magic and homecoming depict characters from the peninsula and resonate with a piquant humour and imagination. Deep knowledge and a love of the local pervade Michael Kirby's writings. They remind the reader of the wonders and simpler joys in a life that he celebrated with such spirit.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Ähnliche

Skelligs Sunset

MICHAEL KIRBY

CONTENTS

Title Page

Preface by Mary Shine Thompson

Foreword by Dáithí Ó hÓgáin

Introduction

Schooldays: Tug of War in the Classroom

‘Voices of Valentia’

Seán Ó Conaill: King of the Storytellers

The Courting of Moll Molloy

The Red Petticoat

‘Our First Forbidden Tryst’

‘Coinne’

Courting Couples and the Parish Priest

‘A Bridal Morning’

Haste to the Wedding

‘A Living Salmon’

Stations of Life

‘Ships that Pass’

Games and Pastimes of My Boyhood

‘The Charming Beagle Hunting’

Silence! Silence in the Court!

‘When I am Free’ 98

The Tale of the Haunted Piper

‘Wild Things’

Mountains: from Canuig to the Appalachians

‘Yearning’

‘Miangas’

Jerry No Name

‘The Fishing Witch’

‘Bathing Beauty’

Piseoga: Old Superstitious Beliefs

‘Sea Magic’

The Night Haul at Bolus

‘South Wind’

‘Please, Mister, Hold My Baby …’

‘Storm Petrel’

Humpty-Dumpty

‘Sea Secrets’

The Giant’s Grave at Coom

‘My Ship Sailed Without Me’

Dan of the Roads

‘Why the Storm?’

Heart Attack and the Drunken Ballet Dancers

‘The Mountain Road’

My Garden

‘Ode to a Wren’

A Painting is Born

‘Who Scattered the Stars?’

A Garden: In the Waning Light of My Years

‘My Lovely Skellig’s Shore’

Afterword by Antony Farrell

Copyright

PREFACE

When Michael Kirby died in April 2005 he left a considerable body of writing in the English language, some of which he had been working on up to the very last months of his life. It includes recollections of life in the Iveragh region of County Kerry during his childhood; essays; poems; folklore and fiction. The work was written with a view to publication as a companion volume to his earlier books, SkelligsCalling and Skelligside. Michael Kirby had even prepared an introduction and chosen a title: it was to be, and is, SkelligsSunset. The title acknowledges his mortality and recognizes that this was to be his last book.

Most of its contents were written in the five years before his death; some pieces, such as ‘Humpty-Dumpty’, ‘My Garden’, ‘Schooldays: Tug of War in the Classroom’ and his ‘Introduction’, as late as 2004. Although he was by then in his late nineties and physically weakened, there was no dulling of his intellect, no falter in his recall of the past. His voice remained clear and distinctive to the end.

However, without his guiding presence, there are some challenges for the editor. In line with his practice and principles, it is likely that he would have reworked at least some of the pieces included here. In the preface to his first book in English, Skelligside, he recalls that the schoolmaster who taught him in the national school in the second decade of the twentieth century ‘was a stickler for accuracy, and when English was in session he would growl and wield his hazel wand, shouting “Watch your grammar!”’ Michael learned the lesson well and displayed great respect for the formality of the written word. His style, therefore, is distinctive and complex: it combines the charm and immediacy of the traditional seanchaí with the self-conscious formality of a written testament.

His family attests to the meticulous care he took in preparing for publication the contents of SkelligsCalling and Skelligside, and the manuscript evidence bears this out. Despite the demands that longhand makes, his habit was to redraft and reshape repeatedly. His script is distinctive: he employs an elegant cursive style. Each letter is carefully formed, and only his last manuscripts betray a slight tremor. Punctuation, however, commands less attention. Some poems, for example, have few, if any, punctuation marks.

Here, then, are pieces at varying stages of readiness for publication. They were transcribed in the first instance by Michael’s son-in-law, Pat Coffey. In many cases all that was required of the editor was to standardize punctuation and spelling and correct the occasional grammatical or syntactical infelicity: many pieces bear the imprint of Michael Kirby’s own critical reworking. However, some, in particular the stories, required more attention. Some digressions from the plot of the story ‘Jerry No Name’ were excised, as was some extraneous detail. Less substantial were the changes made to ‘The Courting of Moll Molloy’. Some titles were modified. However, the chief editorial principle employed was restraint. The distinctiveness of the voice and the leisurely narrative approach were respected. Furthermore, it seems that the tales told here are worthy of inclusion for reasons other than their narrative economy: Anne Coffey confirms that many were based on real events. Secondly, they derive from a tradition tolerant of a narrative approach that takes a scenic route before arriving at its destination.

The organizing principle adopted was that of a miscellany. The works are not presented either in the sequence in which they were written or according to genre (poetry, story and so on). Rather, they are broadly attuned to the rhythms of Michael Kirby’s life. Thus, autobiographical material on childhood is placed near the beginning, together with memories of customs and old ways. Events, tales and information that might reasonably have come his way during adulthood, or that relate to the life of a young man – love, marriage and fishing, for example – come next. Interspersed throughout are poems whose content loosely relates to the lengthier prose compositions. Because Michael Kirby sometimes translated and refashioned work already published – from Irish to English and vice versa – the text of two Irish poems, ‘Miangas’ from ÍochtarTrá and ‘Coinne’ from BarraTaoide, are included alongside free translations, ‘Yearning’ and ‘Our First Forbidden Tryst’. The English version of ‘Miangas’ is published for the first time. (‘Coinne’ also appears, translated by the author, in Skelligside.)

The pieces placed last show Michael, now ‘féscáthnalice’ (‘under the shadow of the gravestone’), to use his own phrase, but at peace with this world and ready for the imminent call to the next. The penultimate essay, ‘A Painting is Born’, ostensibly recounts Michael’s interest in painting, developed only after he reached seventy years of age. However, it also acts as an apologiaprovitasua, a defence of his life, and a statement of its value. Painting may be read in this case as a metaphor for the effort, the care, the shaping that can make sense of a life, almost to the moment when the last breath is drawn.

This collection of Michael Kirby’s last works is enriched by the addition of a foreword written by noted folklorist and scholar Dáithí Ó hÓgáin, who had the privilege of knowing Michael Kirby personally. He offers insights into Michael’s humanity and dynamic presence, he evaluates his achievement, the literary and folk contexts that illuminate his work, and the breadth of his reading and knowledge. His essay will evoke the man and the place to those who come to Kirby and the Skelligs for the first time; and it will affectionately recall him to his friends.

I am greatly indebted to Anne Coffey and Pat Coffey for their assistance while editing this collection. In addition to being diligent proofreaders, they offered unique insight and invaluable guidance in interpreting Michael Kirby’s approach to his writing. Maureen Granfield Hufnagle, Michael’s grand-niece from Medfield, Massachusetts, and Timothy Kirby Forde, Michael’s grandson, also assisted with proofreading.

GodtugaDiasuaimhneassíoraíd’anamdílisMhichíl.

Mary Shine Thompson, Editor

FOREWORD

During the Easter holidays in 1971 I was in County Kerry, trying to find out all I could about poets and poetry in the whole area west of Killarney as far as the sea. This had been for centuries one of the most learned parts of Ireland, the stamping ground in the nineteenth century of Seán Crón and Séamas Crón Ó Súilleabháin, Siobhán Ní Iarlaithe, Diarmaid Ó Gealbháin, Seán Ó Siochrú, Diarmaid Ó Fáilbhe, Micheál Ó Meára, Seán Vácúir Ó Súilleabháin and many more. I spent several days in the shadow of the Macgillicuddy Reeks searching for lingering memories of these old poets and legendary accounts of their travails, their courage, and their magical speech; a whole tradition that had been receding since the time of the Great Famine. Folklore collectors under the direction of Professor Séamus Ó Duilearga – and particularly the brilliant folklorist of Iveragh, Tadhg Ó Murchú – had, a generation or two earlier, assembled a large body of such lore, as well as many substantial oral poems that would otherwise have been lost forever.

I wanted to find out if anything of any relevance had been left uncollected, and in my work I got most generous help from several people in that whole area – Killarney, Glencar, Glenbeigh, Killorglin and Beaufort – that helped to fill in the history and local context. Everything was fitting into shape, but there was one major remaining problem – there were some words and expressions found in no dictionary but put to fine creative use by these old poets of a century and more before, and I needed somebody with special knowledge of the specific Irish dialect of south-west Kerry to help me with this. So I went farther west, and I found my man; a man who in addition to being a native speaker of Irish since his birth was also himself an accomplished poet. That man was Michael Kirby.

The first thing I noticed about this man of Ballinskelligs was that he had the bearing of a chieftain. A very tall man, already advancing in years, but with unusually handsome looks, a slow and deliberate voice and a fine aesthetic sense. Most striking of all, however, was his quiet manner, born of a natural courtesy and of the mind of a philosopher. Michael was already a painter, a poet, and a deep thinker, but– looking back now on the generation and more that has passed since then – I, in common with many others, continue to be amazed by what he accomplished from that time onwards. It was as if a whole lifetime of observation, of thought, of investigation, of speculation and of computation had welled up within him and had begun to flow as a mighty river of creative energy. The hue of that river had indeed been touched, and repeatedly so, by the beautiful surroundings in which he grew up and by the love and companionship of his wife and family and friends, and its surges had been carried along by the tremendous vitality of the old language in which he was an expert. But, whatever its nature or its sources, that great river of creativity broke out when he was already an elderly man and, for the next twenty years and more, he produced book after book in both languages and covering a wide variety of styles and themes. I know of nobody else who began writing so late in life (he undertook it in a serious way only when he was in his late seventies), or who finished writing so late in life either: in the months before he died, almost in his hundredth year, no longer physically able to write, he continued to dictate his thoughts. In this regard Michael must forever stand as a unique figure in the literature of our country.

Michael Kirby (or Mícheál Ua Ciarmhaic, as he was better known) was born in Ballinskelligs in 1906, the youngest of a family of seven. His four brothers and two sisters all emigrated to the USA and settled there. He himself spent a short period on the other side of the Atlantic also. He married a local girl, Peggy O’Sullivan (Peig Ní Shúilleabháin), in 1943. They had six children, Anne, John (who died of meningitis at the age of two), Martina, Declan, Margaret and Tim. Always well known and held in affection and respect locally, he became known nationally through his writings. He died on 6 April 2005 and is buried in the new cemetery in Kinnard, half a mile from his home.

He was a great conversationalist, possessing an extraordinarily liberal mind for a man of his generation, engaging brilliantly with young and old on a wide variety of subjects, subjects to the significance of which he always added an extra dimension of his own. His wisdom was clear to all who heard him comment on topics as diverse as artistic theory, Irish history and folklore, world politics, fishing and farming, economics and community development. He loved to debate, but always in a spirit of inclusiveness, and rancour was never known to enter into his speech or mentality. He often described himself as a student of the world, and he was this in the fullest and widest sense. It has often been remarked that, in addition to its wonderful colour of expression, to survive and strengthen the Irish language needs to spread its wings wider and cover an ever-expanding scope of interest in the contemporary world. Michael showed the way in this – his interests being all-embracing and yet rooted in the lilting rhythm that, as a celebrated scholar once remarked, is everywhere the sign of the true Irish speaker.

He loved to tease out the origin and nature of expressions in Irish, and spent long periods helping students and others in elucidating difficult points of idiom and grammar, but always did so with patience and with a genial sense of humour. It goes without saying that he solved my problems with the Iveragh poets for me and gave me much additional information besides. He was particularly interested in the artistic image of the poets, and it took me no length of time to realize that the reason for this lay in his own creative temperament. He spoke of Irish poets and scholars of the past – especially of Aodhagán Ó Rathaille, Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin and Tomás Rua Ó Súilleabháin – as if he knew them personally; and, indeed, so well did he himself embody that great tradition that it would not be entirely untrue to say that he did know them. They were neighbours of his in the realm of lore and legend, of verse and imagery, just as were his neighbours of the contemporary world such as the rhetorical speaker Fionnán Ó Siochrú from Dún Ghéagáin and the magnificent storyteller Dónall Ó Murchú from Rinn Ruaidh. To a young student of Irish tradition, such people opened up new vistas at the same time as they offered age-old insights into the heritage of Ireland.

Like Fionn MacCumhaill in the heroic sagas, Michael was a man with knowledge of the past, of the present and of the future. He took a special interest in his family history and could tell of how relatives found themselves on different sides in the American Civil War, as well as how at home they managed to survive the tyranny of landlords and the famines and other vicissitudes of history in the south-west of Ireland. He could go back further. Aware of how the Ua Ciarmhaic sept originated as Eoghanacht kings at Cnoc Áine Cliach (Knockainey in County Limerick), he often speculated on how several of them ended up towards the western Atlantic. He once wrote a letter to me describing an aisling or vision that he had one night, when he dreamed that he was back in County Limerick as king of all the rich landscape of the Golden Vale of Munster. He did this of course with a puckish sense of humour, knowing that I was a native of that area, but two aspects of the letter were significant. Firstly, he was reiterating the old Munster tradition of a poet being vouchsafed a vision, and secondly the letter was written entirely in verse and after the revered old style. Much of the appeal of Michael as a literatus was this understanding that everything must be done with style and panache, and that it must echo the inherited cultural values from past ages.

But he was also a man of the present. He showed this through his poetry, short stories and novellas; and in equal degree through his many radio broadcasts and television appearances. In these he demonstrated originality and independence of mind, and his genial presence captivated and influenced the hearers. Books came from him in a steady flow. In Irish he wrote CliathánnaSceilge (1984), ÍochtarTrá (1985), AnGabharsaTeampall (1986), BarraTaoide (1988), RíochtnadTonn (1989), CeolMaidíRámha (1990), IníonKeevac (1996) and GuthónSceilg (2000). Parts of these works have been repeatedly anthologized and broadcast on radio. Then there were the two very valuable collections of his works in English, Skelligside (1990) and SkelligsCalling (2003), that gained an even wider readership and established him as a leading writer in a county noted for its leading writers. His books were widely and favourably reviewed, literary prizes were awarded to him, and he was fêted and celebrated, yet he never changed. He remained to the end the true writer, humble and creative and always seeking to hone his art to greater achievement.

He numbered among his friends some of the leading poets, writers, artists, and scholars of twentieth-century Ireland, influencing them by his measured approach to culture and his inspired view of his native place. The cassette-tape of his lore, entitled ChuireasMoLíonta, appeared in 1992 and was an immediate success, being highly valued for the material and as the record of the speaking voice of one of the Gaeltacht areas richest in lore down to our own time. Especially popular was the television documentary on Michael and his life and interests entitled TheGoatintheTemple (1995) – here he made use of an old proverb that became very popular with him and which is the nearest he ever got to satirizing human failings.‘Máthéannangabharsateampall‚’ he would remark, ‘nístadfaidhségohaltóir,’ meaning ‘If the goat goes into the temple he will not stop until he reaches the altar.’ This he used in the title of the book in Irish in which he expressed opinions on a wide variety of subjects. The title draws attention to the sometimes crude contemporary world, which Michael lamented just as much as he welcomed; the increased scope for young people to express their opinions and play their full part in social and cultural affairs.

For Michael was also a man of the future, a factor that is especially evident in his great affection for and championing of the environment. In this regard, RíochtnadTonn is a little masterpiece, simple in description, yet deep and significant in the knowledge and detail, both linguistic and biological, that has gone into it. Very few other people in the Ireland of our time have had such a minute knowledge of the sea, of its plants, birds and fishes. Michael was an expert fisherman, but was also a great lover of all living things and combined the lot in the mind of the humanist and of the artist. He was unflinching in drawing attention to the natural beauty around us – a trait not surprising, one might say, in a native of such a beautiful and colourful part of Ireland, except that Michael possessed such a trait in so full a measure. His family recall the great joy in growing up with such a father, how he brought them on nature excursions by land and sea, how he drew their attention to the continuous changes in colour and mood of the environment, and the example he showed by his understanding of and affection for the various creatures. Like all people of culture, he was a keen observer of things and of events, many of which happen only in the wilderness and far from ordinary human eyes. In his final years, he enjoyed very much feeding the robins that came at his whistle in wintertime, and in the summer he watched carefully for the bees and butterflies that seemed to find particular pleasure in landing on his straw hat.

People from all over the world used to stop and have the most amazing conversations with Michael, and he continued to entertain even when age and failing health was causing him some distress. They would come just to talk, more usually to learn, to buy one of his paintings, or have him sign a copy of one of his books. Often he would dispense with the formalities and just give a painting or a book as a present to a visitor. In his own spare time, he would do some gardening or chat to his family or to neighbours, all of whom understood well that he was a special person, akin to the fine Irish poets and scholars of old and yet with a very modern perspective. Otherwise, he was continually reading: science books, novels, poetry, essays, biographies and books on history. He took a particular interest in travel books, and from these and from his many visitors, as well as his own brief experience abroad, he knew and sensed so much that he was a genuine cosmopolitan in feeling and sentiment.

I have many heart-warming memories of Michael, beginning with the welcome he and Peig gave to me when I first arrived in Ballinskelligs, followed by his in-depth description of the surroundings and the traditional life of land and sea, and progressing into his recitation by heart of reams of poetry and discussion in the grand old style of one proverb after another until late into the night. I remember also his gentle teasing some years later when he realized that I met my future wife Caitríona while holidaying in Ballinskelligs, and later visits of his to Dublin – especially for a painful eye-operation – when in the Gaelic League Club on Harcourt Street he assured us that suffering did not matter to him so long as he was among friends. I remember especially the day that Peig and himself were unexpected but most welcome visitors to the Folklore Department at University College Dublin, on which occasion he presented me with tapes of all his stories, recorded in the most charming Irish.

Fondest of all memories is a more recent one, when his family told me that his wife Peig was sorting out his effects and came upon a memorial card in his wallet. It was the memorial card of my father, who had died in 1982. I had given it to Michael at that time, and he had kept it by him ever since. The two men never met, but they had one distant thread binding them. Both had a connection with Knockainey – my father, an athletic little man, had come there from Kilkenny to train race-horses; Michael, a great big man, was descended from a remote ancestor who had left Knockainey to wrestle with Manannán’s horses in the sea. I am sure that they would have had an affinity with each other, and that they have met and discussed many things in an afterlife in which they both, like myself still, firmly believed.

Michael had a great love of the sea and a keen interest in boats and ships of all kinds, being particularly proud of the one-sail fishing boat that he used in his youth and that held special memories for him. He was an expert seaman, and even in advanced years could navigate the dangerous sea-passage to Skellig Michael, the place of the strange but wonderful old monks that he glowed in describing. In this, as in other matters, his recall of scenery and situation was impressive. Such a clear brain made him an excellent farmer and fisherman, but it also made him an expert judge of words. Every word of his – mingling with the imagery that illumined his thought – called forth a phrase, a proverb, a verse, a story.

Of his works, my mind still revolves upon one of the simplest of all the pieces, an item that nevertheless has a resounding meaning for human life in all its contexts. This is his Irish translation of a beautiful little poem, ‘Time’, which – looking back now – is always increasing in poignancy. I beg to quote it in its entirety and then to give my own translation. [The original English poem also appears at the end of Skelligside– ed.]

Golagussuanimnaíonándom

– amró-bhuan.

Garsúngáireacbcainteachumhal

– amagsiúl.

Cuisleanfhirimchorpagcrith

– amagrith.

Fáirbríaois,dronnaguspreiceall

– amageiteall.

Isgearrgombeadféscáthnalice

– amimithe.

Cries and sleep as I am a baby

– time too eternal.

A boy laughing, garrulous and obedient

– time is moving.

The man’s pulse quivering in my body

– time is running.

Wrinkles of age, stoop and double chin

– time is flying.

Soon I will be under the shadow of the flagstone

– time is gone.

C’estlavie‚ we might say, but it is my great pleasure to introduce to readers a fine selection of his work. It is a miscellany, a form of writing in which he excelled and that is in accord with his own speaking voice, relaying the variety of tradition and all the while interpreting it with a keen eye. This is the distinguishing mark of Michael, a vigorous prose and contemplative poetry that teeters between tradition and the individual talent. It is very much a nostalgic record of the past, and many people will value it for that, but it also contains within it flashes of inspiration that are at one with universal art. Michael may have been the last of his type in Iveragh. In a sense – given the breadth of his interests – he was the only of his type, but most of all he was a really nice man, a sincere and enlightened one. And that surely is the finest tribute of all that can be paid to a writer.

Dáithí Ó hÓgáin, Associate Professor, Irish Folklore, University College Dublin

Cobh,30January1930:MichaelKirbystanding,MichaelMoranseatedtoleft,DavidFitzgeraldtorightofphotograph.

Skelligs Sunset

INTRODUCTION

I am thankful for the simple gifts: the ability to see, hear and observe the things of nature, the rocks, bogs, meadows, sand and seashore of my native place, including birds and animals. All these I took for granted. My people were and still are, thankfully, just simple folk. We were part of the plan of nature. Whether the day was wet or dry, stormy or fine, people in general said: ‘Thank God.’

Now in my last two years, trying to finish a century, I humbly attempt to describe nature. Nature is beautiful, bountiful, fearfully awe-inspiring and mysteriously enigmatic. One part of nature’s scene has held a special fascination for me: the ever-changing sequence of cloud formation. During my many years as a fisherman I developed an admiration for the arch of the sky during sunrise and sundown. I believe, in my heart and soul, that no human artist can ever emulate patterns that become visible in the embryo of pristine nature.

It was eventide, a light, lazy, rolling swell covered the darkening blue of the sea, reaching westwards to the horizon; a perfect setting for a spectral and ethereal display. Suddenly, the great star stood poised momentarily on the line where the arch of the firmament meets the ocean. Molten rivers of fire streamed upwards like raised arms in adoration, in its centre a blinding whiteness. My mundane thoughts suffered a severe jolt that evening. I could only think of the Transfiguration of Jesus: ‘His face did shine as the sun.’ (Matt. 17: 2)

The sea between Skellig Michael and Bolus Head became an undulating pathway of sparkling golden light, swaying and shimmering. The clouds took on a wondrous array of colour. In the background, white cumuli thunderheads kept rising like snow-clad peaks whose valleys and gorges filled with complementary hues. Some clouds resembled angry bearded prophets. One dappled brown cloud resembled a baboon holding its monkey-like grey-faced offspring in a protective embrace. The last rays of the sinking star tinted the clouds with roseate pink and yellow kisses before departing. Turning, I could only say: ‘Thanks be to God!’

MICHAEL KIRBYFEBRUARY 2004

SCHOOLDAYS: TUG OF WAR IN THE CLASSROOM

Fond memories pass through my mind, making mental pictures of the past, my early boyhood and most of all my school days and companions.

Ballinskelligs National School for boys and girls opened in 1867, employing four teachers and consisting of two separate adjoining schools for male and female within the one building. My name was entered on the school roll in 1911 at the early age of five years. My only book was called TheFirstBook, and it contained little words like ‘at’, ‘cat’, ‘bat’, ‘rat’ and so on. I do not remember other books. I heard my parents speak of a book called the Readamaidaisy or ReadingMadeEasy, which was its proper title. Another book called TheThreeRs they called Readin’, ’Ritin’ and ’Rithmitic.

I remember being transferred from infant grade to first class. I now possessed a lovely small paper table-book that I soon learned to sing like a song: ‘One and one is two, two and two is four,’ and so on. The teacher helped me to write, showing me how to balance the pencil between the forefinger and the thumb, by placing his open palm over my small hand, guiding my pencil across the page and forming the contour of my first letters. Gaelic lettering was different, having more tails. I found the contrast between Irish and English scripts a bit confusing. I had no difficulty in understanding Gaelic, it being our most used language at home and in the workplace.