11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Bedford Square Publishers

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

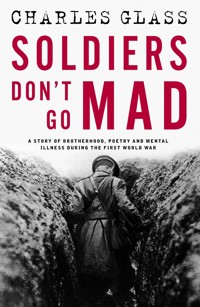

A brilliant and poignant history of the friendship between two great war poets, Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, alongside a narrative investigation of the origins of PTSD and the literary response to World War I 'Recommended not only to psychiatrists but also to those with an interest in the complex relationships created by war and the management of trauma' British Journal of Psychiatry Second Lieutenant Wilfred Owen was twenty-four years old when he was admitted to the newly established Craiglockhart War Hospital for treatment of shell shock. A bourgeoning poet, trying to make sense of the terror he had witnessed, he read a collection of poems from a fellow officer, Siegfried Sassoon, and was impressed by his portrayal of the soldier's plight. One month later, Sassoon himself arrived at Craiglockhart, having refused to return to the front after being wounded during battle. As their friendship evolved over their months as patients at Craiglockhart, each encouraged the other in their work, in their personal reckonings with the morality of war, as well as in their treatment. Therapy provided Owen, Sassoon, and fellow patients with insights that allowed them express themselves better, and for the 28 months that Craiglockhart was in operation, it notably incubated the era's most significant developments in both psychiatry and poetry. Drawing on rich source materials, as well as Glass's own deep understanding of trauma and war, Soldiers Don't Go Mad tells for the first time the story of the soldiers and doctors who struggled with the effects of industrial warfare on the human psyche. As he investigates the roots of what we now know as post-traumatic stress disorder, Glass brings historical bearing to how we must consider war's ravaging effects on mental health, and the ways in which creative work helps us come to terms with even the darkest of times.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Praise for Soldiers Don’t Go Mad

‘Thoroughly researched and lucidly written, this is an immersive look at the healing power of art and a forceful indictment of the inhumanity of war’

Publishers Weekly

‘A lucid, comprehensive and highly engaging account of a watershed in British medical and literary history’

Sebastian Faulks, author of Birdsong, Charlotte Gray, and Snow Country

‘In Soldiers Don’t Go Mad, Charles Glass has created a remarkable chronicle of the timeless interplay between war’s destructive but also creative forces. This is a story of friendship and of art, of war and of madness, and the way the former might save us from the latter’

Elliot Ackerman, author of The Fifth Act: America’s End in Afghanistan

‘Novels and films have been devoted to Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, but Charles Glass’s elegant non-fiction account has an indelible poetry of its own. Surprise and suspense, character and conviction, horror and heroism are seamlessly woven together in a fast-moving narrative. The contrasting settings — an idyllic retreat in Scotland for officers suffering from “shell shock” versus the hell of trench warfare “where youth and laughter go” — will break your heart’

Christopher Benfey, author of If: The Untold Story of Kipling’s American Years

‘A riveting history of Scotland’s Craiglockhart War Hospital, a progressive and peculiar oasis for British officers at a time when mental illness among soldiers was all too often dismissed as cowardice. Charles Glass chronicles the lives of the shell-shocked, from the poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen to uncelebrated men whose stories demand our attention, and devotes the same nuance and grace to their deeply compassionate physicians. Soldiers Don’t Go Mad is a timely, essential reminder that wars carry on well beyond the truces and treaties that formally end them’

Elizabeth D. Samet, author of Looking for the Good War: American Amnesia and the Violent Pursuit of Happiness

‘Not only a beautifully written book, but an extremely important one. While writing a poignant chronicle of the patients and doctors who sought to overcome battlefield “shell-shock” at the Craiglockhart War Hospital in World War I, Glass has also penned a profound testimonial on the resilience of the human spirit, of the bonds forged between those caught in the maws of war, and those who would help them. A splendid and haunting achievement’

Scott Anderson, author of Lawrence in Arabia and The Quiet Americans

‘An absorbing, well-researched addition to the expansive canon of World War I literature’

Kirkus

‘A stunning account of poetry, paradox, and the horrors of war . . . [Glass evokes] the power of war to haunt, traumatise and destroy long after the last bombs explode’

Salon

‘Glass writes a simple, honest, straightforward engrossing history of the epic scale of post-traumatic stress disorder during the First World War as studied in Craiglockhart Hospital near Edinburgh. The narrative includes many individual case studies that make the war real’

Robert S. Davis, New York Journal of Books

‘Deeply researched . . . These were haunted men. But the brief respite offered by Craiglockhart proves a fascinating subject’

Charles Arrowsmith, The Washington Post

‘[A] brisk, rewarding account of the innovative doctors and their “neurasthenic” patients who suffered unprecedented psychological distress (and in unprecedented numbers) on the Western Front’

David Yezzi, The Wall Street Journal

‘Glass . . . delivers a clear picture of how poetry of the war . . . shifted not just from jingoistic to critical, but also sought out new metaphors for the agonies of the trenches, concerned as much with soldiers’ psyches as their bravery . . . the heft of Soldiers Don’t Go Mad demonstrates how powerful two writers with a shared sensibility can be, even in a short period of time’

Mark Athitakis, writer for The New York Times and The Washington Post

‘Glass captures the distinctive environment of Craiglockhart and its dynamic treatment for shattered psyches, though he is careful to point out that many “cured” officers would suffer trauma for the rest of their lives. Heartrending and inspirational, Soldiers Don’t Go Mad is a moving elegy on the power of art to express the inexpressible’

Peggy Kurkowski, Shelf Awareness

SOLDIERS DON’T GO MAD

Charles Glass

In grateful memory of Rob Morrell, Alessandro de Renzis, and P. J. O’Rourke

And it’s been proved that soldiers don’t go mad

Unless they lose control of ugly thoughts

That drive them out to jabber among the trees.

—SIEGFRIED SASSOON,

“Repression of War Experience,” 1917

CONTENTS

Cover

Praise for Soldiers Don’t Go Mad

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

CHAPTER ONE. The Hydro

CHAPTER TWO. The War Hospital

CHAPTER THREE. Interpreting Dreams

CHAPTER FOUR. A Complete and Glorious Loaf

CHAPTER FIVE. Out of Place

CHAPTER SIX. A Young Huntsman

CHAPTER SEVEN. The Protest

CHAPTER EIGHT. Poet by Day, Sick by Night

CHAPTER NINE. High Summer

CHAPTER TEN. Mentors and Novices

CHAPTER ELEVEN. Who Die as Cattle

CHAPTER TWELVE. The Celestial Surgeon

CHAPTER THIRTEEN. A Grand Gesture

CHAPTER FOURTEEN. Fight to a Finish

CHAPTER FIFTEEN. Love Drove Me to Rebel

CHAPTER SIXTEEN. Things Might Be Worse

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN. A Second Chance

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN. Drastic Changes Were Necessary

CHAPTER NINETEEN. Mad Jack Returns

CHAPTER TWENTY. The Loathsome Ending

EPILOGUE

Plate Section

Acknowledgments

Notes

Image Credits

Index

Also by Charles Glass

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

All the armies in the Great War had a word for it: the Germans called it “Kriegsneurose”; the French “la confusion mentale de la guerre”; the British “neurasthenia” and, when Dr. Charles Samuel Myers introduced the soldiers’ slang into medical discourse in 1915, “shell shock.” Twenty-five years later, it was “battle fatigue.” By the end of the twentieth century, it became post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

In December 1914, a mere five months into “the war to end war,” Britain’s armed forces lost 10 percent of all frontline officers and 4 percent of enlisted men, the “other ranks,” to “nervous and mental shock.” An editorial that month in the British medical journal The Lancet lamented “the frequency with which hysteria, traumatic and otherwise, is showing itself.” A year later, the same publication noted that “nearly one-third of all admissions into medical wards [were] for neurasthenia”—21,747 officers and 490,673 enlisted personnel. Dr. Frederick Walker Mott, director of London’s Central Pathological Laboratory, told the Medical Society of London in early 1916, “The employment of high explosives combined with trench warfare has produced a new epoch in military medical science.”

This development need not have surprised Britain’s military physicians. Major E. T. F. Birrell of the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) had observed nervous breakdowns in surprising numbers while supervising a Red Cross medical mission to the Balkan Wars between Turks and Bulgarians in 1912 and 1913. The new heavy weapons that Germany’s Krupp and other European industrialists sold to both sides inflicted carnage that doctors had not witnessed before. Modern science was creating modern war. Explosive rifle cartridges penetrated flesh more deeply than balls from single-shot muskets. High-explosive artillery shells released not only the shrapnel shards of old, but ear-shattering thunder, blinding light, and a concussion so fierce that it sucked the air away. The shells demolished the strongest ramparts, leaving no refuge. Rapid-fire machine guns mowed down hundreds of men in an instant. Hospital wards received, in addition to those who had lost arms or eyes, disabled soldiers without marks on their flesh. They suffered unexplained blindness, mutism, paralysis, shaking, and nightmares. A surgeon from Belgium’s Saint Jean Hospital, Dr. Octave Laurent, documented the Balkan wounds in his book La Guerre en Bulgarie et en Turquie. Laurent removed metal shards from broken bodies, but surgeons could not cure paralysis, trembling, nightmares, blindness, stammering, and catatonia.

Laurent posited physical causes for the symptoms. This accorded with medical and military doctrine of the day that fighting men did not become hysterical. Practitioners in the new field of psychiatry shared the view of Sigmund Freud in Vienna that hysteria, a word derived from the Greek for “uterus,” was a female condition. Laurent referred to the soldiers’ malady as la commotion cérébrospinale, a variant of what American Civil War doctors had called “windage,” undetectable molecular disruption of the spinal cord from the vibration of speeding bullets and shells. Concussion had caused some, but not all, of the neuroses. Laurent’s and the RAMC doctors’ denial of the emotional causes of physical disabilities would influence the military response to mental illness when Europe’s Great War began in the summer of 1914.

Industrial-era weaponry deployed on a mass scale from August 1914 to November 1918 exacted a greater toll in dead and wounded than in any previous war. For the first time in history, millions of men faced high-velocity bullets, artillery with previously unimaginable explosive power, modern mortar shells, aerial bombardment, poison gas, and flamethrowers designed to burn them alive. British casualties soared on August 26, 1914—a bare three weeks into the war—when German artillery ravaged the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) at Le Cateau in northeast France. In October, the Battle of Ypres produced so many cases of mental shock that the War Office dispatched a leading neurologist, Dr. William Aldren Turner of London’s National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic, to France to discover the causes. Examining otherwise healthy men afflicted by deafness, deafmutism, blindness, stammering, palsies, spasms, paraplegia, acute insomnia, and melancholia, he concluded, “In many instances he [the soldier] may persevere with his work until a severe psychical shock—such as seeing one of his friends killed beside him, severe shelling, an upsetting experience, or bad news from home—unsteadies him, and precipitates a definite attack of neurasthenia, requiring rest and treatment at home.” As the war progressed, doctors recorded an escalating proportion of mental breakdowns alongside the usual statistics of killed, wounded, and missing. The percentage increased as the war froze along a static cordon of opposing trenches from the English Channel south more than four hundred miles to the border of neutral Switzerland. Along this deadly frontier, troops of both sides endured the relentless hammering of devastating artillery in a dark underground world from which the only escape was injury or death.

Debate among military physicians and between doctors and senior officers raged over how to deal with the unblooded wounded. Dr. Myers criticized the military for regarding shell-shocked soldiers as “either insane and destined for the madhouse or responsible and should be shot.” The question persisted throughout the war: should men who broke down on the field of battle be disciplined or receive medical attention? By war’s end, firing squads had executed some, practitioners had administered punishing electric shocks to others, and psychiatrists offered Freudian psychoanalysis to a lucky few. But even then, the treatments’ purpose was to thrust shattered boys and men back into the violent conditions that had caused their breakdowns, troubling physicians who had to weigh duty to patients against military necessity.

The problem of soldiers’ mental health became a crisis in the summer of 1916, when British general Sir Douglas Haig launched an all-out assault to break the German line in northern France’s Somme Valley. Preparatory, uncamouflaged massing of forces and supplies, together with a weeklong artillery barrage to reduce enemy defenses, alerted the Germans to the impending onslaught. At 7:27 on the morning of July 1, British artillery subsided and an eerie silence prevailed. Two minutes later, a mountain of earth rocketed into the sky from a spot behind the German lines called the Hawthorn Redoubt, where British sappers detonated a 40,000-pound underground charge. That was the signal for thousands of men laden with 66-pound backpacks to climb over the parapets of the British trenches and march into No Man’s Land. German defenders, who had sheltered deep under the surface during the barrage, emerged to fire machine guns, artillery, and mortars at their attackers. Twenty-one-year-old Captain Wilfred Nevill, known fondly as Billie to the men of his East Surrey Regiment, kicked a soccer ball onto the battlefield and charged forward. As he dribbled the ball into the barbed wire, German gunners cut him down. A fellow officer, Lieutenant Robert Eley Soames, followed with another ball, urging the men to kick it into goal. Few of them made it.

Novelist and official war propagandist John Buchan, whose swash-buckling imperial heroes like Richard Hannay had inspired many youngsters to volunteer, described the carnage in his 1917 book, The Battle of the Somme: “The British moved forward in line after line, dressed as if on parade; not a man wavered or broke rank; but minute by minute the ordered lines melted away under the deluge of high explosive, shrapnel, rifle, and machine-gun fire.” The Germans pitied the boys falling before their bullets, calling them Kannonenfutter, cannon fodder.

It was not combat so much as slaughter. Between dawn and dusk, nearly twenty thousand British soldiers died, while another forty thousand suffered wounds or went missing in action—the highest one-day loss in British military history before or since. The men and boys who straggled back to their trenches had witnessed unprecedented horror. Close friends, in some cases their own brothers, had been cut to pieces before their eyes. It was more than many could bear. Thousands turned up in Casualty Clearing Stations (CCS) without visible wounds but unable to speak, hear, walk, or stand still. Many were incoherent. Some, fearing terrifying nightmares, dared not sleep. They came from all ranks, a high proportion of them junior officers. Haig pressed the Somme offensive for four bloody months of mounting casualties without breaking through.

Dr. Arthur Hurst, a physician in Britain’s RAMC, filmed many of the broken men. His War Neuroses and The Battle of Seale Hayne depicted men and boys trembling, blinded, paralyzed, babbling, hiding under beds, and frozen in what Americans in Vietnam fifty years later would label “the thousand-yard stare.” Hurst’s motifs resembled those of the epoch’s silent horror movies, stricken creatures struggling with deformities, spectral figures casting sinister shadows against white backgrounds, eyes bulging and transfixed, paralyzed limbs, shaking bodies, all so terrifying that the images were not shown to the public. Although the British Army High Command was reluctant to acknowledge that war wounds could be mental as well as physical, it could not avoid addressing a phenomenon that was depriving the fighting forces of the men needed to prosecute the war.

Many of the broken men recorded their experiences in diaries, letters, illustrations, and poems. Two young officers treated for shell shock, Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, rank among the finest poets of the war. Yet much of their verse would not have been written but for their psychotherapy. Chance brought the two poets together, and chance assigned each to a psychiatrist suited to his particular needs. These analysts acted as midwives to their works by interpreting their nightmares, clarifying their thoughts, and encouraging them in their creations. Owen, who in another context might have been left to languish in trauma, benefited from intensive therapy under Dr. Arthur Brock. Brock’s interest in science, sociology, folklore, Greek mythology, and nature studies accorded with Owen’s. It was Brock who expanded Owen’s horizons and gave him the self-confidence to tackle sundry outside tasks and restore his mental balance. Sassoon, in contrast, enjoyed intellectual engagement with his psychiatrist, Dr. William Halse Rivers, who did not trouble him with the outside activities that Brock imposed on Owen. Had Rivers treated Owen and Brock been responsible for Sassoon, this would have been a different story. Had both young officers been sent to different hospitals, they would not have met, and the poems they wrote would have been vastly different from the masterpieces the world knows.

Following the disaster of the Somme, the War Office opened new hospitals expressly to deal with shell shock and treat what had become an epidemic. The best was a place in Scotland called Craiglockhart.

. . . in this battle of Marathon . . . Epizêlus, the son of Cuphagoras . . . was in the thick of the fray, and behaving himself as a brave man should, when suddenly he was stricken with blindness, without blow of sword or dart; and this blindness continued thenceforth during the whole of his after life. The following is the account which he himself, as I have heard, gave of the matter: he said that a gigantic warrior, with a huge beard, which shaded all his shield, stood over against him; but the ghostly semblance passed him by, and slew the man at his side. Such, as I understand, was the tale which Epizêlus told.

—The History of Herodotus, book 6, chapter 117, translated by George Rawlinson, 1910

CHAPTER ONE

The Hydro

Historians surmise that Craiglockhart took its name from the Scots Gaelic Creag Loch Ard—“crag or hill [on] the high lake,” although the hill boasts neither lake nor great height. There is a pond, but men dug it long after the outcrop received its name. Its twin peaks, known as Easter and Wester Craiglockhart hills, lay claim to the lowest altitude—a bare two hundred feet above the sea—among seven hills that, like Rome’s, defined the topography of Scotland’s capital city. A stone castle protruded from the crag until the thirteenth century, but it played no significant role in the country’s turbulent history of dynastic and religious wars. It was already rubble when the Act of Union sealed Scotland’s connection to England in 1707. By the nineteenth century, a southwestern suburb of Edinburgh, Slateford, had absorbed the crag while retaining it as a rural sanctuary.

The crag’s woods and meadows afforded a pastoral retreat from the somber stone mansions, filthy tenements, and notoriously disputatious politics of the city. Craiglockhart boasted unpolluted air, pure underground water, and panoramic views, not only of Edinburgh’s spires a mere three miles northeast, but of the Firth of Forth estuary and the twenty-mile ridge of green wilderness known as the Pentland Hills. These natural advantages of curative waters, smokeless skies, invigorating vistas, and proximity to the capital’s wealth attracted a company of canny Scots merchants to erect a health spa of gargantuan proportions on thirteen fertile acres.

Expense was the least consideration for investors who engaged two of Scotland’s most prestigious architects, John Dick Peddie and Charles George Hood Kinnear, in 1877 to design the extravagant Craiglockhart Hydropathic Institution. This was the era of sumptuous health retreats for beneficiaries of Britain’s growing imperial bounty to “take the waters.” More than twenty such establishments sprang up in late nineteenth-century Scotland beside the lochs and up the glens, promising respite from counting houses, mills, and coal-infused air. Peddie and Kinnear adopted a design similar to another luxurious spa they were building forty miles northwest of Craiglockhart, near the town of Dunblane. Both hydros would be massive fortresses of fine-cut ashlar sandstone playfully mixing Italian Renaissance motifs with the stolid mass of a Scots baronial manor.

In 1878, workers demolished an old farmhouse, laid foundations, and erected scaffolds on a grassy hillock facing west from Wester Craiglockhart Hill. Over the following months, the villa’s imposing 280-foot-wide façade took shape, soaring from deep basements up three stories of bay windows and a classical balustrade to a pitched gray slate roof. Peddie and Kinnear mimicked fashionable styles from Doric columns on second-floor windows to a Japanese pagoda capping the five-story central tower’s Italian belvedere. Wings at either end stretched behind and housed four floors of long corridors and multiple bedrooms. Turret-like gables and chimneys at irregular intervals lent the otherwise brooding structure a fairy-tale aura. A 50-by-20-foot swimming pool with Turkish bath in the basement offered, in the promoters’ words, “all the varieties of hot and cold plunge, vapour, spray, needle, douche and electric baths.”

Outdoors, gardeners cleared pathways through a forest of beech and Scotch pine. The landscape provided acres of lawns for an archery range, bowling greens, tennis courts, and croquet grounds. Harried Scottish burghers could exercise without straining themselves.

The mock classical exterior belied interior conveniences as modern as any in Victorian Britain, including indoor plumbing for water closets, showers, and baths. The Tobin system of interior ventilation, metal tubes within wall cavities to recirculate the air, filtered smoke from the many fireplaces in bedrooms and common rooms alike. Guests could tumble out of bed, step down a marble staircase, and skip along the 140-foot hallway to the dining room for a full breakfast of porridge, eggs, bacon, sausage, black pudding, toast, and tea. From there, they could wander into the billiard room, reading room, or Recreation Hall. Those in need would find the office of the medical superintendent, Dr. Thomas Duddingston Wilson, on the ground floor.

The Craiglockhart Hydropathic’s elegant portals opened to Edinburgh’s “worried wealthy” in 1880. Carriages and hansom cabs deposited patrons from Edinburgh at the foot of the stone walkway leading up a grass verge to the villa. Guests, while valuing the Hydro’s amenities, proved too few to cover the costs of construction, maintenance, staff, and taxes. The owners sold it in 1891 to a fellow Scotsman, fifty-year-old architect James Bell. Bell already managed Peddie and Kinnear’s Dunblane Hydro, which he left to live and work at Craiglockhart as principal shareholder and managing director. He renamed it the Edinburgh Hydropathic.

Accompanying Bell to Craiglockhart was Dunblane’s head gardener, forty-one-year-old Henry Carmichael. The rugged and conscientious Carmichael brought his wife, Catherine, and their eleven children to live in one of the “Hydro Cottages” on the Craiglockhart property. Two of the older boys assisted their father with the lawns, shrubs, flowers, and woods. Catherine bore two more children, Archibald, known as Archie, and Elizabeth, at Craiglockhart. In tribute to Henry’s employer, Elizabeth’s middle name was Bell. Soon after the girl’s birth, Catherine contracted typhoid. No doubt weakened from bearing and rearing thirteen children, she died on August 1, 1894. Henry cared for the children with the help of his oldest daughter, Janet, until 1897, when he married again. His second wife, Mary Comrie, gave the family one more son, John, and another daughter, Euphemia.

Like the Carmichael family, Craiglockhart’s gardens flourished. Henry and his older sons seeded and mowed grass fields for the Hydro to host the Scottish Croquet Championship in July 1897. The precision with which the Carmichaels nurtured the grounds led to the championships’ taking place there for seventeen more years. Bell took part in the competitions, and he proudly presented the prizes at the conclusion of each tournament.

Bell’s astute management transformed the Hydro’s fortunes. Its reputation spread, attracting rich patrons in want of rejuvenating therapies. The kitchen provided hearty Scottish fare, the Carmichaels maintained the grounds, maids kept the bedrooms in good order, and athletic staff guided overweight plutocrats in exercises and games to mitigate the effects of years of indulgence. Craiglockhart’s popularity pointed toward good fortune as the new century approached.

Craiglockhart, along with the rest of Britain, mourned the death in 1901 of Queen Victoria, who had popularized holidays in Scotland with her acquisition of Balmoral Castle and her many summers there. The transition from Victorian to Edwardian eras with the accession of King Edward VII continued the Hydro’s prosperity, as gentlemen and ladies from England as well as Scotland sought its cures. On Edward’s death in 1910, his son George V inherited a kingdom whose subjects envisioned a long reign of peace.

Events in the summer of 1914 dispelled their illusions: the assassination by a Serbian nationalist of the Austrian grand duke at Sarajevo in June, Austria-Hungary’s ultimatum to Serbia, the mobilization of continental armies from France to Russia, and, on August 4, Imperial Germany’s invasion of Belgium. Britain declared war on Germany the same day, a decision few in Scotland or England questioned. The secretary of state for war, Lord Kitchener, appealed for volunteers to join his expanding New Army. Young men, among them the Edinburgh Hydropathic’s patrons and workers, converged on military enlistment centers throughout the empire. In Scotland, volunteers were so numerous in early August that Edinburgh’s recruiting bureau stayed open all night. Two of Henry Carmichael’s sons, Archie and Alexander, enlisted in the Royal Scots Regiment in September. One grandson, John Henry Carmichael, also joined the colors in 1914 to serve in the Royal Field Artillery. Soon afterward, Henry’s youngest son, John, who had been born at Craiglockhart, became a signaler in the 8th Battalion of the Regiment of Scottish Rifles, popularly called the Cameronians. With three sons, a grandson, and two of his nephews in the armed forces, Henry Carmichael relied on his other boys to help with the backbreaking work of keeping the grounds up to prewar standards. By this time, Carmichael was sixty-four.

The Carmichael boys, like all the other volunteers in the first wave of recruitment, were unprepared for warfare in the modern era. Raised on tales of imperial battles against Indian rebels and Zulu warriors, they harbored the patriotic delusion that battles would be decisive, few would die, and victory would be swift. Lieutenant Bernard Law Montgomery, who would live to command British armies in the Second World War, was not alone when he wrote, “At least the thing will be over in three weeks.” The poet Rupert Brooke welcomed the release from peacetime ennui:

Now, God be thanked Who has matched us with His hour

And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping.

Cavalry officers carried lances and their infantry counterparts brought swords across the English Channel to face the Germans. They were soon disabused of romantic ideas about gallant battles and a rapid conclusion. By Christmas, when many imagined they would have beaten the “Hun,” a million would be dead. More were wounded in body and mind. Horses, swords, and lances proved useless against German fire-power. Men were returning to Britain with tales of explosives whose force sucked the air out of their lungs and ripped open their eardrums. A man could die of internal injuries without a projectile touching him. A new kind of war was leaving men with new types of injury. It was enough to drive anyone crazy.

DESPITE THE WAR, James Bell hosted the Scottish Croquet Championships at Craiglockhart as usual in September 1914. Spectators from Edinburgh and farther afield converged on Henry Carmichael’s immaculately trimmed lawns, while Bell competed against croquet masters from Scotland, England, Ireland, and Wales. Bell awarded the trophy to a twenty-four-year-old Englishman, Gaston Wace. Patriotic disapproval of such frivolity in wartime, however, forced Bell to cancel future competitions for the duration.

The Carmichael boys posted letters from their training camps and the front lines to the family at Craiglockhart. Private Archibald Carmichael, twenty-four years of age and a hearty five foot ten and 154 pounds, wrote to assure them of his good health before he embarked from Liverpool on May 25, 1915, aboard His Majesty’s Transport (HMT) Empress of Britain. The ship reached Alexandria, Egypt, on June 1. Eight days later, Archie’s 4th Battalion of Royal Scots sailed from Alexandria to reinforce their beleaguered comrades on the beaches of Germany’s ally, Ottoman Turkey. Britain had launched an amphibious invasion on April 25 at Gallipoli, where British, Australian, New Zealand, and French troops suffered nine thousand casualties in the first week.

No further letters arrived from Archie, but his platoon commander, Lieutenant R. Mackie, wrote to his twenty-seven-year-old sister, Elizabeth, from Turkey. Mackie’s family owned the shop where Elizabeth worked, J. W. Mackie & Sons confectioners, on Edinburgh’s elegant Princes Street. “I grieve very much to have to send you such sad tidings of your brother Archie,” the letter began. Mackie explained that a shell burst had struck her brother in the head, wounding him too severely for doctors to save him. Archie, he wrote, was “a quiet steady young soldier whom we all liked and now miss.” Mackie hoped the family would take consolation knowing that Archie had not suffered. Henry Carmichael continued to tend the gardens, knowing that other sons, nephews, and a grandson faced the same dangers Archie had.

Scotland, unlike England’s south coast that reverberated to artillery blasts from the French side of the English Channel, was aloof from the war until Sunday night, April 2, 1916. At 7:00 p.m., Edinburgh police announced that two German Navy zeppelins, the giant dirigibles invented by Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin in 1900, were cruising over the North Sea toward the city. Similar airships had already bombed industrial centers and naval bases in England, but this was their first foray so far north. Although Edinburgh lacked air defenses, the fire brigade, Red Cross, and security services mobilized to deal with casualties and fires.

The first zeppelin appeared just before midnight, bombing the docks at Edinburgh’s Port of Leith and setting Innes & Grieve’s Scotch whisky warehouse on fire. Following the course of the river known as the Water of Leith, it bombarded neighborhoods on both banks. The high explosives and incendiaries devastated two hotels, several houses, and many business premises. One bomb narrowly missed the highest landmark in the city center, Edinburgh Castle.

Soldiers stationed in the castle manned its famed One O’Clock Gun, a 32-pound ceremonial cannon that had fired daily since 1861 for ships’ captains to set their clocks. Blank charges, however, did not deter the airships. The second zeppelin trailed the first over the city, releasing most of its explosives on empty fields.

The raid, visible from Craiglockhart, lasted thirty-five minutes. Seventeen German incendiaries and seven high-explosive shells had taken thirteen lives and left twenty-four wounded. Among the dead were a one-year-old baby and a soldier, Private Thomas Donohue of the Royal Scots, on leave from the trenches in France.

The war, which Edinburgh’s citizens knew secondhand from newspapers and their sons’ letters, had come to Scotland. Its mental victims were not far behind.

CHAPTER TWO

The War Hospital

At the outbreak of the late European War,” wrote British Army psychiatrist Dr. C. Stanford Read, “there was little foresight shown or preparations made for a large influx of mental cases.” Dr. Read ran the army’s only mental asylum, the Royal Victoria Hospital’s D Block in Netley, Hampshire. Founded in 1870, D Block was better suited to locking up the incurably insane than to returning men to normal life. It had only 121 beds for enlisted men and 3 for officers, insufficient for the thousands of mental cases the Great War was turning out every month. The government needed more beds, more hospitals, more psychiatrists, more nurses. It opened psychiatric institutions, starting in November 1914 with a special hospital for officers beside London’s Kensington Palace, and Moss Side Red Cross Military Hospital at Maghull near Liverpool. Maghull filled to capacity within two months, forcing the War Office to requisition additional hospitals throughout the British Isles—“hospitals,” not “asylums,” wrote Dr. Read, “to obviate, if possible, the stigma that might be felt to attach to the name.” In 1915 alone, nervous collapse claimed 21,474 officers.

As the Somme bled Britain’s armed forces throughout the summer of 1916, the War Office turned to James Bell’s Edinburgh Hydropathic. Its swimming pool, Turkish bath, common rooms, and twelve rural acres offered essentials for traumatized officers to begin their recovery. The government requisitioned the Hydro, and Bell moved to another property he owned nearby. The Hydro required little renovation. The massive villa had beds for 174 patients with two or three to a room. Its administrative offices easily converted to psychiatric consulting rooms. It was as if Peddie and Kinnear had designed Craiglockhart for victims of shell shock.

Craiglockhart War Hospital opened in October 1916 for “officers only.” Segregating officers from men was common practice in all European armies. No one questioned the separation of officers from “other ranks” in any realm, be it dining, accommodation, or, in this case, mental health treatment. Military necessity provided an additional motive for concentrating medical resources on officers. They were desperately needed at the front, where they were dying and breaking down out of all proportion to their numbers.

Craiglockhart’s O. C., officer commanding, was fifty-year-old physician Major William H. Bryce of Scotland’s Lowland Field Ambulance. Although a career officer in the RAMC since his 1903 enlistment in Glasgow, Bryce recoiled at military formality. It was his belief, he wrote, that “there should be little to indicate hospital régime beyond the few regulations necessary to ensure order.” His priority was the welfare of patients rather than arbitrary rules of etiquette and dress. Parade ground drill had no place in his mental hospital. It did not bother him if patients wore bathrobes and bedroom slippers all day. His own uniform often lacked a cap and the officer’s traditional cross-shoulder Sam Browne belt. Subordinates were not required to salute him; and, as one astonished observer at the hospital noted, he “spoke to his Staff as equals!” While such affronts to military propriety irritated his superiors, Bryce’s objective was not to break men, but to make them whole.

Bryce in the autumn of 1916 benefited from the presence of two remarkable psychiatrists, who excelled as much at psychology as in fields far removed from medicine. It seemed they understood Trinidadian intellectual C. L. R. James’s famous question long before he wrote “What do they know of cricket who only cricket know?” The principal medical officers were a Scotsman, Dr. Arthur John Brock, and an Englishman, Dr. William Halse Rivers. Both had qualified as neurologists and psychiatrists. Brock’s other interests, on which he wrote and lectured, were sociology, rural Scotland, classical Greece, and the relationship of mental health to the environment. Rivers had sailed as an anthropologist to South Sea islands, Egypt, and India; made scientific studies of eyesight and nerve regeneration; and written books on color perception, primitive tribes, kinship, and heredity. Brock’s and Rivers’s extracurricular interests diverged, but the two shared a humanistic, holistic approach to mental illness at odds with the era’s military orthodoxies. Most senior officers, including many Medical Corps physicians, regarded shell shock as nothing other than malingering or cowardice that demanded not treatment, but punishment. Brock and Rivers, encouraged by Major Bryce, sought to demonstrate that sympathetic therapy worked better than harsh discipline.

PHOTOGRAPHS TAKEN AT Craiglockhart show a clean-shaved, lean, tall, and ascetic Arthur Brock in his starched captain’s uniform, usually at his desk. Aged thirty-eight in 1916, he had a high-pitched voice, abundant energy, and what one patient called “a long peaked nose that should have had a drip at the point.” He adorned his consulting room in Craiglockhart’s villa with objects akin to his intellectual pursuits: a pen-and-ink drawing of a wrestling match between two stripped and entwined ancient Greek wrestlers and, on shelves below, volumes of Greek myths, ancient medical classics, and Scots Gaelic folklore alongside texts by his mentor, Scottish sociologist Patrick Geddes.

Brock was born just outside Edinburgh on September 9, 1878, the son of a gentleman farmer and a poet, Florence Walker. On completion of his degree in classics at Edinburgh University, he planned to become an artist. When his father vetoed that career, he enrolled in medicine at Edinburgh in 1896. A meeting with Patrick Geddes, an autodidact Renaissance man regarded in Scotland as the father of town planning, had a profound influence on the young medical student. Twenty-four years his senior, Geddes introduced Brock to the philosophies of Auguste Comte and Henri Bergson, kindled his interest in sociology, and taught him the importance to mental health of environment and community. The admiration between the two men was mutual, Geddes writing that Brock was “pragmatic in mind, activist in temper, not content with any specialised view or treatment.”

Brock spent months in Europe’s preeminent centers of psychological discovery, Vienna and Berlin, both before and after graduation in 1901, to expand what he called his “mental horizon.” A succession of Scottish hospitals employed the young physician, notably Woodburn Sanatorium for Consumptives in 1910 and 1911. His study of tuberculosis patients gave him insights into depression that would serve him at Craiglockhart. He noted that at Woodburn “even a patient with only mild tuberculosis soon goes to pieces morally if he has nothing to do.” In line with Geddes, he believed that lengthy rest was more curse than cure. Patients needed to walk outdoors, to study the world around them, and, most important, to work. Idleness was lethal.

In 1915, Brock married Swedish physiotherapist Siri Marianne von Nolting and enlisted in the army. His first posts were aboard hospital ships to India and off the coast of France, where he ministered to casualties straight from the front lines. His next assignment was as medical officer at the Aldershot Garrison, “the home of the British Army,” in Hampshire. While there in 1916, he completed his translation of On the Natural Faculties by second-century C.E. Greek physician Galen. Brock believed Galen, along with Hippocrates a father of medical science, had much to teach modern doctors about natural healing and close observation of disease.

The army transferred Captain Brock to Craiglockhart in time for its inauguration. The shell-shock hospital seemed to him “a microcosm of the modern world, showing the salient features of our society (and especially its weaknesses) intensified, and on a narrower stage.” With his wrestlers’ sketch suspended like a banner over garish floral-print wallpaper, his eclectic library stacked on shelves, and notebooks open on his desk beside a wicker wastepaper basket, Brock prepared to test his and Geddes’s theories on men shattered in the most merciless test of endurance that history had yet contrived for young warriors.

BROCK’S COLLEAGUE AT Craiglockhart was one of the most accomplished scholars of his generation. Dr. William Halse Rivers was a polymath with notable achievements in neurology, clinical psychiatry, medical research, anthropology, and linguistics. Yet the impression he gave on first meeting was of shyness and diffidence. He stammered when he spoke and tired so easily that he was often unable to work more than four hours a day. The four hours nonetheless were more productive than the full days of younger, healthier men. Born near Chatham in Kent on March 12, 1864, Rivers was fourteen years older than Brock. Unlike his clean-shaved colleague, Rivers sported a swirling moustache and wore wire-rim glasses. Where Brock took inspiration from classical medicine and Geddes’s sociology, Rivers applied lessons learned from peoples whom most Europeans regarded as backward. His empathy for South Sea islanders and other colonized peoples diminished his faith in, as he said, the “Great White God.” “I have been able to detect no essential difference [in intellectual concentration] between Melanesian or Toda and those with whom I have been accustomed to mix in the life of our own society,” he wrote, displaying a mind free of prejudice and receptive to fresh ideas. One such idea was Freudianism, which Rivers had studied, as had Brock, in Germany.

The Riverses were a naval family. Two ancestors, a father and son both named William, fought at Trafalgar aboard Admiral Horatio Nelson’s flagship, HMS Victory, in 1805. The younger Rivers, then a seventeen-year-old midshipman, was wounded in the mouth and lost a leg during the battle; but he went on fighting and allegedly killed the Frenchman who fatally wounded Nelson. Family legend had it that Nelson’s last words were “Take care of young Rivers.” The midshipman’s son, who would become William’s grandfather, was the last Rivers to serve in the Royal Navy. His son, William’s father, Henry, became an Anglican clergyman. Henry and his wife, Elizabeth Hunt, had four children, William, Charles, Ethel, and Katharine, between 1864 and 1871. Although Henry was also a speech therapist, he failed to address William’s stuttering.

The speech impediment was not the boy’s only handicap. At the age of five, he walked up the stairs of the family house and entered a room. What happened there must have been traumatic. From that day, he had no visual memory. Loss of the ability to see images in the mind, aphantasia, from the Greek for “absence of imagination,” was so rare that it would not receive a name in medical literature for many years. Only in dreams could Rivers conjure images of people, places, and objects. Not even in dreams, however, could he recall what occurred in that upstairs room.

William and his brother, Charles, attended boys’ day schools together, first in Brighton and later in Tonbridge, Kent. William’s intention on leaving Tonbridge School was to follow his grandfather and father to Cambridge University, but illness kept him out of his final year and prevented his sitting for the scholarship examination. A friend and colleague, Grafton Elliot Smith, recalled that he “always had to fight against ill health: heart and blood vessels.” Rivers studied instead at the University of London’s teaching hospital, Saint Bartholomew’s, becoming, in 1886 at the age of twenty-two, its youngest ever Bachelor of Medicine and member of the Royal College of Surgeons.

Rivers’s poor health prevented him from pursuing a career, like his illustrious forebears, in the Royal Navy. In 1887, however, he signed on as ship’s doctor for voyages to Japan and North America. His love of the sea saw him taking vacation cruises to Norway, Portugal, Madeira, the Canary Islands, and the United States. While sailing home from the West Indies, he enjoyed lengthy conversations with Irish wit and playwright George Bernard Shaw. Saint Bartholomew’s awarded him a doctorate in medicine in 1888, after which he served a two-year residency at the Chichester Infirmary. Next came research in neurology and psychology back at Saint Bartholomew’s. Curiosity about the brain and nervous system led him to the National Hospital for the Relief and Cure of the Paralysed and Epileptic in London’s Queen’s Square. Rivers was drawn to Germany, as Brock would be, to learn more about psychology. Spending 1892 in Jena and Heidelberg, he mastered German, studied philosophy as well as psychology, and attended concerts and art exhibitions. It was not long before he was publishing academic papers in German. With the German experience heightening his interest in the mind, he noted in his diary, “I should go in for insanity when I return to England.” So he did, practicing at London’s Bethlem Royal Hospital, founded in 1247 as England’s first mental asylum and known in the vernacular as “Bedlam.”

Achievements mounted, from a lectureship at University College London, to another at Saint John’s College, Cambridge. Saint John’s gave him a place to live in its cloistered grounds beside the River Cam. His students felt free to call on him in his rooms at any time. One recalled that “he had an extraordinary way of making us feel that we were taking part in a discussion on a plane of equality with him.” He became founding director of England’s first two psychology laboratories in London and Cambridge. Lured in 1898 by his medical students Charles Samuel Myers, who would later coin the term “shell shock,” and William McDougall, Rivers ventured on a rigorous expedition to the Torres Strait between Australia and Papua New Guinea to study the islands’ inhabitants. Going out as a doctor, he returned a dedicated anthropologist. It was a discipline his maternal uncle, James Hunt, founder and first president of the Anthropological Society of London, had pioneered. Rivers’s methodology for ethnographic research and classification became standard practice. He traveled to Upper Egypt in 1900, to the Toda people in the Nilgiri Hills of southeast India in 1901 and 1902, and, five years later, to the Solomon Islands in Melanesia to study customs, kinship, and color perception. His books on the Todas in 1906 and the Melanesians in 1914 became instant classics in the emerging discipline of anthropology.

While practicing and teaching psychology in London and Cambridge, Rivers continued his work in anthropology. In the summer of 1914, he was in Australia attending an anthropological conference of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, when Britain and Germany went to war. British and German scientists alike sailed home, but Rivers went to the New Hebrides to do field research. He returned to England in the spring of 1915 and immediately volunteered for frontline service in the RAMC. The army, considering the fifty-year-old physician’s health too fragile, turned him down.

Dr. Grafton Elliot Smith recruited him in July as a civilian psychiatrist at Moss Side Military Hospital, then becoming the preeminent treatment center for the war’s mentally wounded. Among its clinicians were the two former students who had accompanied Rivers to the Torres Strait, Charles Samuel Myers and William McDougall. The patients were not officers, but “other ranks.” Rivers found that healing them was hindered by their distrust of authority, inhibitions about their private lives, and suspicions that doctors wanted to trick them into saying something that would return them to the front. Their intellectual and educational level, compared with that of his Cambridge students, further distanced Rivers from them. The conscientious psychologist persevered, working himself to exhaustion while keeping up with academic research.

In October 1916, the War Office sent him as a commissioned RAMC captain to Craiglockhart. The “officers only” establishment allowed Rivers to discuss with educated young men their dreams, the causes of their collapse, and the restoration of their mental health. The challenge had awaited him all his professional life, and he embraced it. “Rumour has it,” wrote a Craiglockhart inmate, “that when a fresh convoy arrived, Capt. Rivers walked round them & took his pick. Strange to say, nearly all the interesting patients floated his way.”

THE RED CROSS SUPPLIED most of the hospital’s nursing and ancillary staff from its Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs), mainly young women of all classes seeking to help the fighting men. Craiglockhart’s seven staff nursing sisters, eighteen VAD junior nurses—among them Scottish ingenues Florence Mellor, Mary McGregor, and Grace Barnet—and the housekeepers worked under the supervision of Matron Margaret MacBean. Miss MacBean, a formidable Scotswoman born in 1864, the year of Rivers’s birth, had entered the nursing profession at the age of twenty-three. With twenty-four years in general hospitals behind her, she became matron in 1911 of the Govan District Asylum at Hawkhead near Glasgow. A letter of reference from its medical superintendent, Dr. James H. MacDonald, stated, “She is not only a highly trained and experienced nurse but a most efficient Matron, who commands the respect and esteem of the Staff and patients alike and, indeed, all with whom she comes in contact.” Some colleagues referred to her as “the fiery matron.” Her responsibilities encompassed nursing staff, kitchen, laundry, and housekeeping. It was a coup for Craiglockhart to engage a nursing director who, despite not having served in the military, claimed five years’ experience in mental health. The War Hospital was seeking excellence in all aspects of the care of traumatized soldiers.

Henry Carmichael persevered as head gardener, assisted by the sons who had not gone to war. Summer gave way to the chilly Scottish autumn. Purple foxgloves and pale hedge bindweeds were wilting, beech and ash leaves changing color and falling to earth. While the Carmichaels burned leaves and dead branches in glowing bonfires, Rivers’s and Brock’s first patients staggered into Craiglockhart.

CRAIGLOCKHART’S INITIAL INTAKE of eight officers arrived on October 27, 1916, in a state of shock, eyes glazed and barely able to take in their surroundings. The oldest was thirty-four-year-old John Sandison. Edward Curwen and Gilbert Davidson were thirty-two, John Douglas twenty-seven, and John Oliver twenty-six. The youngest, George Lightfoot, Charles Greaves, and Ernest Clayton, were twenty-two. All were second lieutenants, all “neurasthenic.”

Second Lieutenant Sandison came to Craiglockhart straight from the Somme’s Transloy Ridges, where twelve days earlier German artillery buried him alive and left him unconscious for thirty-six hours. The men who dug him out found a trench shovel stuck into his abdomen and shrapnel embedded in his left ankle. Sandison, a company commander in the 10th Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders Regiment, had no memory of the explosion that nearly killed him. His legs were immobilized and wracked with pain.

Sandison’s long military record gave the lie to a common belief that only fresh recruits, unaccustomed to military discipline, broke down at the front. The six-foot-three-inch Scotsman had joined the Royal Scots Regiment in 1898 at age sixteen and retired in 1912 as a quartermaster sergeant. That should have ended his military career, but the war drew him back, first as a sergeant in the Royal Scots and, from spring 1916, as a commissioned officer in the Seaforth Highlanders. He had endured the Somme slaughter for three and a half months before coming to Craiglockhart. Soon after he checked in, he met the psychiatrist who would treat him, Dr. Arthur Brock.

Brock’s therapy revolved around the ever-present portrait of the mythological wrestling match between Hercules and Antaeus framed on his wall. It was no haphazard decoration in an otherwise dreary medical office. Brock, the classicist and translator of ancient Greek texts, explained to Sandison and his other patients that the picture was a metaphor for their predicament. The giant Antaeus, a fearsome king in Libya, was the son of the sea god, Poseidon, and Gaia, goddess of the earth. His prodigious strength emanated from the ground, his mother earth, the way Samson’s did from his hair. When the hero Hercules arrived in Libya, Antaeus challenged him to a wrestling match. Hercules threw Antaeus to the ground again and again. Each time Antaeus hit the earth, his muscles grew. Realizing the source of his opponent’s power, Hercules lifted Antaeus into the air and broke his back. Brock felt that each officer at Craiglockhart “recognises that, in a way, he is himself an Antaeus who has been taken from mother earth and well nigh crushed to death by the war giant or military machine.”

The key for Brock was to ground his charges in everyday reality through vigorous physical and mental activity. He encouraged patients like Sandison to rise early, “take a cold bath or swim before breakfast,” then to go outdoors and survey the land. Some officers locked themselves in the lavatories to avoid the doctor’s wake-up calls, until Brock had the bolts removed. One patient “boasted that if he lay flat under his bed, so that the untidy bedclothes hid him, as if he were an early riser, he escaped.” While Craiglockhart offered cricket, golf, badminton, water polo, tennis, and two full-size billiard tables, Brock recommended more productive pastimes like carpentry, photography, debating, music, and writing. Cure depended on reintegration into a community through productive labor. His mantra, derived from Geddes, was “Place-Folk-Work,” with productive labor connecting the patient to his environment and to the community. Brock took the name of his method, “ergotherapy,” from the Greek for “work,” ergo, and for “healing,” therapeia. It was the cure for “ergophobia,” fear of work.

Brock rejected American Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell’s popular prescription for neurasthenics in Philadelphia: rest, massage, isolation, and a milk diet. War hospitals utilizing the Weir Mitchell therapy produced mixed results that left some patients in long-term lassitude. The worst course for any patient, in Brock’s view, was to confine him to bed. Moreover, he believed, hospitals that advised traumatized soldiers not to think about the war were hindering their recovery. His psychoanalysis required soldiers to confront and thus render ineffective memories of their disabling experiences. Finally, he insisted his patients become self-reliant: “If the essential thing for the patient to do is to help himself, the essential thing for the doctor to do—indeed, the only thing he can profitably do—is to help him to help himself.” Brock had encountered neurasthenic symptoms in civilians before the war. “Shell-shock,” he observed, “was but the pre-war ‘nervous breakdown’ with added terrors and frightfulness.”

The “added terrors” included asphyxiation by chemical weapons of the kind Second Lieutenant George Walpole Lightfoot survived on September 2, 1916, on the Somme at Delville Wood. All the Royal Welch Fusilier (RWF) officers and men beside him died in the gas attack, but stretcher-bearers found Walpole unconscious and carried him to the nearest CCS. Three days later, doctors declared him a shell-shock case. A ship ferried him with other wounded to Southampton on September 16, a date, like that of his gassing, that he could not remember when asked. A Medical Board of RAMC physicians at the 4th London General Hospital noted: “He looks pale & ill. He has a cough and there is a little soreness in the sternum . . . He is startled by noises and is troubled by terrifying dreams. He is very weak and is unable to stand any fatigue.” The board ordered him to report to Craiglockhart on its opening day.

Thirty-two-year-old Edward Curwen fell to poison gas in April 1916 near Loos in front of the Germans’ fortified Hohenzollern Redoubt, where he was serving with the British 12th Division’s Trench Mortar Battery. An art teacher in Scottish secondary schools before the war, the blue-eyed subaltern, junior officer, received treatment at a base hospital in France. When his lungs recovered, his superiors sent him back to the front. There he suffered a nervous collapse. He wrote, “I was compelled to go to hospital on October 3rd after being about 10 weeks on the Somme.” The Medical Board that examined him in France sent him to England on October 20 and, six days later, to Craiglockhart.

The same Medical Board examined Canadian John Douglas of the Seaforth Highlanders’ 7th Battalion and commented that “he had been 13 months at the front. He feels very shaky & incapable of any sustained bodily or mental effort.” At Eaucourt l’Abbaye, a shell that exploded a few feet from him killed two of his friends and trapped him under a ton of debris. When comrades dug him out, his hands trembled, his head ached, and nightmares blighted his sleep. The once healthy, five-foot-six-inch Toronto native had enthusiastically answered the call of King and Country in September 1914 at the age of twenty-four. By the time he reached Craiglockhart, his hair was gray.

Another casualty from Eaucourt l’Abbaye, Percy Pickering, came to Craiglockhart on its second day. The twenty-year-old second lieutenant of the Royal Welch Fusiliers’ 18th Battalion stood five feet seven inches and weighed 136 pounds. He had enlisted in December 1914 and received his commission the following September. On the front lines, heavy artillery blew him off his feet and left him bleeding. He refused to leave his men. Physicians, noticing that he “was unable to control much twitching” and suffered headaches, insomnia, and depression, pulled him out of the line. A Medical Board in France examined him on October 9, concluded that his injuries were “Severe. Not permanent,” and recommended treatment in Britain. Care of the dazed youngster fell to Dr. Brock.

Two days after Pickering arrived, Second Lieutenant Alexander Scott Freeman of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders limped through Craiglockhart’s portals. Genuine physical ailments had afflicted him since November 8, 1915, when a high-explosive shell wounded him at the hotly contested Hill 60 near Ypres in Belgium. When an appendectomy failed to relieve his stomach pains, doctors put him on a diet. That worked so badly they had to pump his stomach. While recuperating, he contracted pneumonia and gastritis. The twenty-three-year-old soldier, who had enlisted in the first month of the war, was a mental and physical wreck by the time a Medical Board examined him on October 27, 1916, and wrote that “his admission to Craiglockhart War Hospital is strongly recommended.”

The first eight officers and those who joined them in the following weeks lounged in the common rooms, read newspapers, smoked, traded gossip, and enjoyed a variety of sports as if they were rich clients of the old Hydro. Craiglockhart seemed more officers’ club than mental asylum. Major Bryce wrote, “The officers’ hospital should be run socially on the lines of a country house, or, more correctly speaking, on the lines on which a country club might be organized.” Doctors encouraged the men to write to their families and in some cases to invite their wives or parents to visit. Craiglockhart’s surface normality reassured its patients that they had no cause for shame and their minds could heal like broken legs. Normality reigned by day. At night, though, chilling screams echoed along bare corridors to the terror of young VAD nurses.

While the nightmares distressed their victims, Dr. William Halse Rivers saw them as openings to his patients’ psyches. He urged them to discuss their dreams in detail. Although he had studied Freud before the war, he did not begin reading the Austrian’s The Interpretation of Dreams until beginning work at Craiglockhart. Rivers shared Freud’s view that dreams were “wish fulfillment,” but nightmares of unimaginable wartime horror led him also to see “dreams as prominent symptoms of nervous disorder.” Nightmares of those who repressed their memories were the most frightening and persistent. “It has been found over and over again,” he wrote, “that when this process of repression is given up, the dreams no longer occur, or, if they continue, lose their terrifying character.”

Officers in Rivers’s consulting room did not lie on a couch. That “usual analytic procedure,” Rivers felt, produced a “morbid transference” of trauma from patient to doctor that achieved nothing for either of them. Rivers’s patients sat in chairs for face-to-face conversations that made “the analysis a matter in which the patient and I are partners.” He called it “talking therapy,” which he had developed with enlisted men at Maghull but felt he could employ more effectively with the better-educated and less-inhibited officers at Craiglockhart. One of the men he treated, Lieutenant William Evans, recalled that Rivers “had a quick, dry sense of humour that would always seem far ahead of our own. By the time we thought of an answer, he’d be ready with the next line. If you were lucky you got to spot the mischief hidden in his eyes. I used to enjoy those verbal sparring matches and, I think, so did he.” Rivers offered cups of tea, while he drank milk. He let the men narrate their dreams so that “the main lines of analysis were already clear as soon as the dream had been related.” A straight line, he believed, led from dream to cause.

Rivers followed Major Bryce’s lead in eschewing military etiquette. One patient observed that “he had to be forcibly reminded that he must not go his rounds unless fully equipped for all emergencies in full panoply of uniform including cane.” Rather than salute VAD cooks, Rivers bowed courteously, “another grave breach.” Some of those he treated, like his students at Cambridge, remembered the way Rivers pushed his eyeglasses up his forehead and clasped his hands around one knee when an idea excited him. One Craiglockhart patient observed, “When walking he moved very fast, talking hard, and often seeming forgetful that he was being carried along by his own legs.”