Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pitkin

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Stephen Hawking was diagnosed with motor neurone disease at the age of 21 and was expected to live for only another two years. He went on to write books and deliver public lectures right up until his death at the age of 76 in 2018. Hawking achieved commercial success with several works of popular science in which he discusses his own theories and cosmology in general. His book A Brief History of Time, a layman's guide to cosmology, appeared on the Sunday Times best-seller list for a record-breaking 237 weeks and sold more than 10 million copies. As Martin Rees, the cosmologist, astronomer royal and Hawking's longtime colleague wrote, "His name will live in the annals of science; millions have had their cosmic horizons widened by his best-selling books; and even more, around the world, have been inspired by a unique example of achievement against all the odds — a manifestation of amazing willpower and determination." In this concise and informative guide to Hawking's life and work, his key scientific achievements – from gravitational singularities to quantum cosmology – are covered in an approachable and accessible way. This is a celebration of an icon of modern physics, who inspired generations of scientists and changed our understanding of the universe.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 46

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Introduction

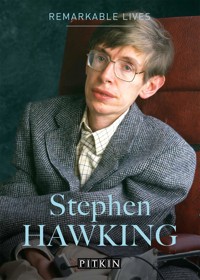

In 1988, the photo of a scholarly-looking gentleman in a wheelchair appeared on the cover of a new book, A Brief History of Time. No one could have predicted the book’s enormous success, or that the face on the cover would soon be familiar worldwide.

Stephen Hawking, whose books and documentaries would lead us into black holes and to the origin of the universe, drew multitudes to his lectures, from Beijing to Cambridge to California. Leaders of governments and science awarded him medals. The media followed him like a rock star. He suffered from a debilitating disease that is usually fatal in two or three years, yet he survived triumphantly to the age of 76. His ashes were interred in Westminster Abbey.

How did an unexceptional schoolboy from St Albans become Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge and one of the most inspiring figures of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries? How did he accomplish all he did in spite of the physical destruction of motor neurone disease, able to communicate only by choosing words from a computer screen by moving his cheek?

The story is incredible, but it isn’t fiction.

In 1983, Hawking was a familiar and easily recognizable figure in the streets of Cambridge and the College courts, but he was not yet an international celebrity.

Childhood

In January 1942, with wartime bombs falling on London, it seemed wise to Dr Frank Hawking and his wife Isobel, living in Highgate, for her to move to Oxford for the birth of their first child. The son born there on 8 January was christened Stephen William. When the boy was eight, his father became head of the Division of Parasitology at the National Institute for Medical Research, and the family moved to St Albans. By that time Stephen had two younger sisters. He had not yet learned to read.

A curious child

The Hawkings spent the summers of Stephen’s childhood in a field at Osmington Mills, on the Dorset coast. They travelled there in an old London black taxi cab with a table added between the back seats for the children to play games while they drove. Once arrived, they camped in a ramshackle gypsy caravan and a large tent. In what had once been smuggler territory, the children explored the rocky beach, and Stephen discovered fossils that first awoke in him a sense of wonder for life on Earth.

Far from city lights, the boy watched the stars – something he would love to do all his life. With his sisters he clambered over rocks and raced across fields and beach, with no idea that his days of climbing and running were numbered . . . no hint of the tragedy that lay ahead, or of the courage he would need to face it. Beginning in his early twenties, he would slowly but inexorably lose his ability to move or speak and be left physically helpless, silent and frozen, slumped in a wheelchair. That fragile figure is now familiar to millions as an intellectual giant of our contemporary world – and among the bravest and most inspiring of its men and women.

The rocky coast of Dorset, where the Hawking family spent summers when Stephen was a child, had once been smuggler territory.

Stephen later said he was grateful that he had a normal, healthy, active childhood before the onslaught of motor neurone disease in his early twenties.

An Unexceptional Student

Between the boy of the Osmington beach summers and the Cambridge graduate student of the early 1960s, locked in a deteriorating body, there were years of growing up in St Albans and as an undergraduate at Oxford. As a schoolboy Stephen was no prodigy. He bothered to learn only what interested him and what he thought useful, and was ranked in the lower half of his class. ‘It was a very bright class’, he later claimed. What did interest him was taking things apart to find out how they worked, mathematics, and building a computer with friends and a favourite teacher. Some at St Albans School recognized that within this mediocre little scholar lurked an interesting mind.

TRIBUTE TO A TEACHER

Hawking wrote of a teacher at St Albans school: ‘His classes were lively and exciting. Everything could be debated. Thanks to Mr Dikran Tahta, I am a professor of mathematics at Cambridge… When each of us thinks about what we can do in life, chances are we can do it because of a teacher.’

Casually inviting disaster

Stephen surprised them all, and his parents, by his sterling performance in entrance exams and interviews for Oxford. However, once there, reading physics as an undergraduate at University College, his slipshod study habits continued. Hawking later calculated he had spent an average of one hour a day studying: about one thousand hours in three years (1959–62) at Oxford.

The chief accomplishments of this casually arrogant, popular young man seemed to be as cox of a college boat, and the occasional show-off remark in a tutorial. In his third year, however, he found himself navigating into deeper waters. He was getting clumsy. He had an unexplained fall down stairs. He was also facing exams that would determine his future.

Stephen (left) and his friends at St Albans School built a remarkable computer that they called LUCE: Logical Uniselector Computing Engine.

Stephen’s light, wiry build, commanding voice, quick intelligence, and fondness for being in control made him an ideal cox of a college boat at Oxford.

Where did the universe come from?