Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Alfredbooks

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

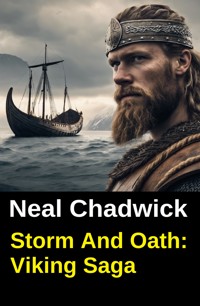

Storm and Oath: Viking Saga Immerse yourself in the harsh world of the Vikings! Heiðabýr, a settlement on the Salt River, stands between storm and oath: King Sweyn Forkbeard calls for attack, old enemies stalk through the night, and powerful merchants from London threaten the community with cunning and hunger. Einar, Ketill, and Astrid fight not only with axe and shield, but with courage, unity, and wise signs against betrayal and overwhelming odds. As the tide of danger rises, the inhabitants of Heiðabýr must learn when to stand firm and when to strike—and that true strength often lies in the oath and song of their community. Experience an epic Viking saga full of adventure, intrigue, and Nordic atmosphere. With gripping battles, mysterious rituals, and unique characters, this saga tells the story of a community that stands up against the powers of the North and the South—forging its own path between tradition and change. For fans of Nordic legends. Order now and relive the Viking Age!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 389

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Storm And Oath: Viking Saga

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Storm And Oath: Viking Saga

Copyright

Oath by the Salt Fire

Night of the Dragon Ships

Blades of the Fjord

The Last Song of the Norsemen

Orientierungspunkte

Titelseite

Cover

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Buchanfang

Storm And Oath: Viking Saga

by NEAL CHADWICK

Storm and Oath: Viking Saga

Immerse yourself in the harsh world of the Vikings! Heiðabýr, a settlement on the Salt River, stands between storm and oath: King Sweyn Forkbeard calls for attack, old enemies stalk through the night, and powerful merchants from London threaten the community with cunning and hunger. Einar, Ketill, and Astrid fight not only with axe and shield, but with courage, unity, and wise signs against betrayal and overwhelming odds. As the tide of danger rises, the inhabitants of Heiðabýr must learn when to stand firm and when to strike—and that true strength often lies in the oath and song of their community. Experience an epic Viking saga full of adventure, intrigue, and Nordic atmosphere. With gripping battles, mysterious rituals, and unique characters, this saga tells the story of a community that stands up against the powers of the North and the South—forging its own path between tradition and change.

For fans of Nordic legends. Order now and relive the Viking Age!

Copyright

A CassiopeiaPress book: CASSIOPEIAPRESS, UKSAK E-Books, Alfred Bekker, Alfred Bekker presents, Cassiopeia-XXX-press, Alfredbooks, Bathranor Books, Uksak Special Edition, Cassiopeiapress Extra Edition, Cassiopeiapress/AlfredBooks and BEKKERpublishing are imprints of

Alfred Bekker

© Roman by Author

© this edition 2025 by AlfredBekker/CassiopeiaPress, Lengerich/Westphalia

The fictional characters have no relation to any real persons. Any similarities in names are coincidental and unintentional.

All rights reserved.

www.AlfredBekker.de

Follow us on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/alfred.bekker.758/

Follow us on Twitter:

https://twitter.com/BekkerAlfred

Visit the publisher's blog!

Stay informed about new releases and background information!

https://cassiopeia.press

Everything about fiction!

Oath by the Salt Fire

by Neal Chadwick

CHAPTER I.

THE OATH BY THE SALT FIRE.

The great hall at Heiðabýr, the port of kings, was so crowded on that early winter evening of 996 that the fresh rushes crunched underfoot and the air hung heavy with smoke, salt, and damp fur. Shields stood against the walls, their painted bosses blazing red and blue in the torchlight; between them hung ancient spears, worn by many hands, and horns with silver-tipped edges. At the front, beneath the carved dragon beam, a salt fire crackled, just as the old seafarers knew it: dried seaweed and a piece of resinous wood smoldered in an iron bowl. It was the custom in Heiðabýr to light the salt fire at great feasts so that envy and false tongues would be consumed by the smoke and oaths would retain the taste of the sea.

King Sweyn Forkbeard sat on the high seat, gazing with pale, sharp eyes over the rows of his guests. The Danish king wore not the large blue cloak brooch bequeathed to him by Harald Bluetooth that evening, but a simple, broad circlet; and yet he seemed taller than usual, for at his feet lay three broad wolfskins, and the angled dragon heads of the supports cast shadows over his head that resembled horns. To his left sat the chieftains of Zealand and Funen; to his right sat the men of Jomsborg, the famous brotherhood whose very name made even distant Saxons reach for their axes.

Two skalds sat on stools in the center, their knees covered with grey blankets, playing the strings of their harps with their fingers as they sang of conquests in the Irish Sea, of gold in the river mud near York, and of heavy horses grazing by the Eider. Their voices were rough, yet carried surely to the very back rows.

Not far from the queen—a pale woman with a calm mouth, yet her eyes still vibrant beneath her lashes—sat two young people, heated and boisterous as flames in a salt fire. One was fair-haired, with narrow cheekbones and a slight smile; the other darker and more alert, his gray eyes flashing sparks like the steel of a freshly oiled sword when he laughed.

"Ketill, you hold that horn like an old man," whispered the dark-eyed man, nudging his companion with his elbow. "Don't lift it like a comb, but like a sail mast; otherwise, it will be obvious that you were born by the sea."

“And you, Einar Palnason,” came the quick reply, “are talking too fast. Did you already knock off that blunt thorn on the worm-shovel this afternoon? I don’t want a fisherman’s boy decorating the planks with your name tomorrow.”

Einar laughed. His laugh had a tone that made heads turn nearby. "The worm guard? My hand would sooner jump off the handle than steal your honor, Ketill Ravenhair. Its edge bites into oak like a walrus into seaweed."

“And yet she squealed on a horse bone yesterday,” came the sharp reply.

"Horse bones!" shouted a girl's voice before anyone could reprimand the two boys. "Who lets you sharpen your teeth on horse bones, Einar? Is the hall now a battlefield kitchen?"

The queen smiled, and the dark eyes of the speaker, a distant niece of the queen, glittered mockingly. Their names were well known in the hall: Astrid of Vendland, the swift, who knew how to tie a cap with a single knot, as tight and yet as light as a seagull takes the wind; Einar Palnason, Palnatoki's grandson, who grew with the bow like a young birch trunk in spring; and Ketill Hrafnsson, whom the men called Raven's Hair, because his fair hair was darker at the ends, like the feathers of a young raven when wet.

“If you want, Astrid,” Einar called, “I’ll stand with you tomorrow behind the halls by the posts at the harbor. Three shots at a shield boss—whoever hits twice, the falcon I got from the Frisians shall go.”

“Your falcon has bad eyesight,” said Astrid. “Three days ago, he was sitting on the roof and didn’t see the fox clearing out the kitchen.”

“He saw him very well,” Ketill raised his horn, looking serious. “He only gave him the chance to run free because the fox had the courage to steal a cooking pot in Heiðabýr. Falcons appreciate courage.”

At these words, laughter broke out, and the laughter jumped like sparks across the rushes. But suddenly it grew quieter, the harps fell silent, and the men carefully moved their stools and benches, for the king rose. He took from a servant the large silver bowl, its rim rippled like the sea, and raised it with both hands. The smoke from the salt fire drifted past him, and he bowed his head as if worshipping something unspoken. Then he drank, and his Adam's apple rose and fell gently as all eyes followed him.

When the bowl was empty, he handed it back, stepped in front of the dragon beam, and placed his right hand on the carved head, whose wood was so smooth that it gleamed in the light. He turned to the men.

“Men of Denmark,” said Sweyn Forkbeard, his voice harsh yet warm, “you know that the sea is never still, and that honor rusts without the sea. Here before the salt fire, where the smoke carries the salt of the North Sea, I swear: Before three winters have passed, no English ship will cut the sea between Heligoland and the Thames, except under my banner. I will gather the fleet and lead it across the Sound, and Ethelred the Perplexed shall hear the sound of our oars in his sleep.”

A soft hissing of breaths ran like a wind through the hall, then a deep, rising murmur, and finally the old custom sprang from every throat: "Skoal! Skoal!"

Horns clashed, swords clashed against shields, and even the oak posts seemed to tremble briefly at the cry. Astrid gritted her teeth slightly. "Look, Ketill," she said, rarely seriously, "the queen has grown paler."

The queen, who rarely uttered a word, had indeed turned her face slightly to the side. A short, thin shadow had crossed her cheeks. Beside her, a man had placed his hands on the table and now tapped it once at most, as if to restore order: Jarl Valthjófr, whom the men called Valthjófr the Broad-Shouldered, captain of the Jomsborg men, a man with a dark beard and a heavy gaze, who rarely laughed, yet when he did, he amazed the ten-year-olds.

“King,” he began slowly, in a voice like the rumble of a cart as its wheels roll over gravel, “I do not have the hand of a king, but I bear the hand of my brothers. We too have our salt to swallow. Hear my oath: Before three winters have passed, the hall of Lade will no longer bear the name of a pagan jarl. Whether Hakon lives or not—his seat will belong to a man who will not trample the cross underfoot.” He spoke the word “cross” in such a way that some of the old men pursed their lips, but there were enough in the hall who understood the sign.

Einar raised his head slightly at the sound of Lade's name. Something stirred within him, something that had been growing for months: a dark, sharp rage against those who had betrayed his father years before. Ketill sensed it and kicked Einar.

"Be careful, Ravenhair," he whispered back, his grey eyes taking on the same cold tone as the salt fire, "don't mention Thorgeir. Not today."

But Einar needed no admonition. Valthjófr had sat down, and immediately—as expected—his younger brother, Thori Longstep, so named because he could step over two oaring places in one stride, sprang to his feet. “I swear by our grandfather’s runes,” Thori cried with gruff fervor, “that I will be the first to enter the gate of Lade! With an axe that shall have a name.”

The men of Jomsborg laughed and clapped their shields. It was part of the game that one oath led to another. And then something happened that was later sung about in some songs as greater than it actually was: A man, not particularly tall, whose traveling cloak was darned in one spot with a red thread, rose and placed his harp on the bench. His face was narrow and as sinewy as his neck, and his eyes were the color of moorland water reflecting the clouds.

“King,” he said, without raising his eyes, “I am no jarl and no son-hunter. I am only a singer, and my name is Kari, an Icelander. I have eaten your salt and I drink your ale. I will not swear, but I will tell what I saw before I came over the sea: I saw in a dream a glowing coal falling from the northern sky, and it fell into a pool of ice. The ice hissed and bubbled, but it remained cold beneath, and the coal did not lose its luster. A man with red hair carried it in his hands, and the bubbles became shield bosses. I do not know what it means—only that he who carries the fire must carry it with both hands if it is not to go out, and that he will burn his fingers before it warms the others.”

A murmur rippled through the hall, half mocking, half superstitious. The king pursed his lips. "Icelander," he said calmly, "may your dreams frighten good-for-nothings and entertain infants. You are a guest in my hall. Sing to me tomorrow of sword and sail, and you will receive a buckle. But dream in silence tonight."

Kari bowed and wrapped the harp back in its wolfskin. As he left, his gaze swept over the corner where the two boys sat—and lingered on Einar, as if he were drawing a line on his face that only he could read.

The voices in the hall rose and fell again, but the merriment was no longer quite the same. It was as if two flames were suddenly fighting each other in the salt fire, one blue and one yellow. Astrid leaned forward and nudged Einar. "Did you see the Icelander? He looked at you as if you'd taken the bread right off his plate."

“He looked at me as if he had seen my face before in the runes,” Einar murmured. “I don’t like that.”

"You're easy to please and hard to bend," Ketill said dryly. "I like that."

A blow to a door-guard's shield made heads turn briefly. A messenger pushed his way into the hall. Snow clung to his hood. He did not kneel—the messengers of the coasts smelled too much of salt to kneel before anyone but the gods and the storm. "King," he cried, his voice rough with the wind, "a boat from the north is at Quernsteen! It comes from the Trondheim Fjord. They're driving burning wood before them, they say, and one of them bears a name that makes the men of Heiðabýr rise up."

"What name?" shouted the king, faster than was his habit.

"Count Eiriksson, known as the Red. Not the one who seeks islands; the Younger. He summons Jarl Valthjófr to his council—tonight."

Valthjófr slowly raised his head, like a bear waking from sleep. "Let them into the hall, two of them. The rest by the fire bowl."

The two men who entered could easily have blended in with the others, were it not for the look in one of them. He was narrow-faced and broad-shouldered, and carried an unadorned sword that hung from him as naturally as the muscles above his wrist. When he threw back his hood, the color of his hair made some women gasp: a red like some chains, covered in old rust, when they see the light for the first time in years.

“King,” he said, “I have little to say. Only this: The loading hall is not yet cold from the smoke. Hakon lives, as the ravens croak, and those who serve him bear names that even Jomsborg croaks. A young man from the south, born on the Eider, harbors a grudge against Thorgeir of Nordmøre. And he who is born on the Eider learns to hear the sea before he understands the voices in the hall. I came to tell Valthjófr: If he wishes to take up his oath not in three winters, but this winter, he shall send men with shield and fire with me tonight, before the ice hardens again on the shore.”

What happened next was strange: not the king, not Valthjófr spoke first, but Einar Palnason sprang to his feet, so quickly that his horn fell over and the ale spilled in a dark semicircle over the rushes. "I'll go with you!" he cried, and his voice was so loud and clear that even the two doorkeepers, who had already heard a thousand shouts, craned their necks in astonishment. "I'll go with you, by my father's bones!"

A wave of unease ran through the men of Jomsborg, for an old name had been spoken, and some considered oaths sworn over the dead more powerful than those sworn over the salt fire. Valthjófr raised his hand, and silence returned. “Sit down, boy,” he said, more slowly than sternly. “Your father led men. You may join them when men lead.”

Einar half sank onto the bench, his hands rubbing his knees. He didn't look at Ketill, but Ketill felt Einar burning inside, and his own heart burned with it, like a small flame on the side of a great fire. The Queen and Astrid had put their heads together. The Queen whispered, and Astrid nodded.

“King,” she said then, without rising, with that certainty given to only a few women, “if the men sail today or tomorrow, they will not sail on a flat current, but on whirlpools and ice. Give them a man from Heiðabýr who can read the sound like a rune. Otherwise, more wood than meat will float home.”

Svein Forkbeard looked at her, and for a moment his gaze softened, so softly that one could almost imagine the man who, unarmed, had placed the deer skull from last autumn into his wife's hand. "Whose hand do you want?" he asked.

“Ketill Ravenhair’s,” said Astrid, even before Ketill could open his mouth. “He hears the rope sing before it chafes, and points the edge at sand when others still see water.”

A burst of laughter rippled through the area, but it was warm laughter. Ketill felt his face grow hot. He wanted to object, but Einar placed his hand on his forearm.

"Do it," he whispered. "Go with me."

“I obey,” Ketill said loudly, and since he was heard, it sounded stronger than he had expected. “But I want to see my falcon in the morning, before we set the first sail, Astrid. You still owe me an arrow test.”

“Your falcon is still blind,” came the sharp reply, “but it will find you when you return home—and if it doesn’t, it will find your skull.”

The king raised his hand a second time. “Enough witty remarks,” he said, his lips once again hardening. “Red Hrafn, your news is worth its weight in salt. Valthjófr, you knew I would raise my banner to the west. If you want the north, do it quickly. I don’t want a burning hall at my back when I tip the seas.”

“I’m going,” Valthjófr said briefly. “Two dozen by morning. Twenty more if the ice holds.”

“And I,” said Thori Langschritt, and his teeth flashed in a smile that was almost like a youth group’s.

“And I,” Einar said again, and this time his voice was deeper, as if it had settled in the few moments since.

“And I,” said Ketill.

"And you?" asked the king, giving a short nod to the Icelander Kari, who was sitting against the wall again with his hands around the harp.

“I’ll go with them,” said Kari; his voice was quiet, but it cut through the sounds like a thin knife. “Not to fight, but to see how the coal is carried.”

“If you cut your fingers,” grumbled a man behind him, “no one will feel sorry for you.”

“If I warm them up,” said Kari, “everyone will talk about it.”

Then the feast was over, as great feasts end: not with an instant, but like a receding tide, slowly, with foam and seaweed. The king gave a signal, and the horns were emptied and laid down; the men rose, some heavy and tired, others light and bustling. Bundles were tied in the corners, and men who intended to ride that night set off with narrow, swift steps, without waiting for ancient counsel. The salt fire crackled once more and then died down as if exhaling. Astrid stayed with the queen until she went to her chamber; then she drew her hood over her head.

"Where do you want to go?" asked Ketill, who threw a coat around his shoulders.

“To the shed by the harbor,” she said. “If you want to see your falcon at dawn, it shouldn’t be hungry.”

"If you feed him, he won't come to me," said Ketill.

“He goes to whomever he wants,” she retorted. “Falcons are free, and so are men, if they are worthy.”

“I’ll see him tomorrow,” said Einar, his voice lightening again. “If he finds you, Ravenhair, so that he’s perched on your head before you even tie the first knot, I’ll pay you for two arrows. If not, you’ll take my best sinew.”

"I'll take your tendons with me, whether the falcon comes or not," Ketill said dryly. "Your tendons are better than your eyes."

Laughter leaped between them for the third time, soft, warm, and with a touch of seriousness in it. The three young people walked together to the door and stepped out into the clear night. The Heiðabýrmeer lay black and smooth, and the stars above it stood sharp as freshly honed knives. From the ships at the quay came the soft clinking of rings as an oar was fastened, and a deep, contented hum as a rope was pulled taut—the sounds of night work, which loved the great sea more than the day.

“What kind of coal was that that the Icelander saw?” asked Astrid, as they walked past the salt fire that was blazing again in an iron bowl in front of the house.

“Perhaps,” said Ketill, “the coal that my grandmother once got from a bog and that kept reigniting when you let it breathe.”

“Perhaps,” said Einar, “a man with red hair who carries both fire and snow. Or…” He paused, and his face returned to how it had been during the feast: narrow, serious, almost aged. “Or an oath that requires two hands lest it slip through one’s fingers.”

"Yours needs both hands," Astrid observed. "And two more besides."

“I will find hands,” Einar said calmly.

“You have mine,” said Ketill. “The question is whether we can find enough hands to hold the rudder when the current changes.”

They stood for a moment, and the wind came in from the sea, brushing coolly across their faces. A few flakes began to fall—not many, but enough to know that the ice would harden again during the night. Suddenly, a figure emerged from the shadows, gaunt and wearing a cloak that almost reached the ground.

“You are going out into the night, Palnason,” the figure said. It was Kari, the Icelander, and his eyes had a strange gleam in the darkness. “Do not carry the coal like a torch being carried through the village—carry it like bread being brought to a hungry person.”

“Your mouth is full of parables,” said Einar. “I’ve heard enough of them today.”

“That’s alright,” said Kari, and a light, short laugh slipped from his mouth, “one Icelander has to listen to another, whether he wants to or not.”

“I am not an Icelander,” Einar said.

“No,” said Kari, “but the coal in our bogs glows longer than elsewhere. Go. I will see before you what the night will bring.”

He left as quietly as he had come. Astrid shook her head. "I don't like him. He reminds me of those fishermen who keep a snake under their cap and feed it in winter so it will bite in summer."

“He reminds me,” said Ketill, “of a man who collects stories. Perhaps he will collect ours when we are old.”

“Are we getting old?” said Einar, and now his smile was back. “I always wanted to know what I would look like with gray hair.”

“You won’t see anything,” said Astrid, “because you won’t have any eyes left if you keep whipping away with your anger.”

“I can see enough to find my way to the bulwark tomorrow,” Einar said. “And now let’s sleep, if we have to. Tomorrow the hall will be quiet and the harbor loud.”

They parted ways in the corridor: Astrid to the right, where the women's quarters were, pale and warm; the two boys to the left, where the benches were covered with furs and the large, dark shadows of the stacked shield piles looked like sleeping whales. Ketill lay down, smelled the scent of salt and wool, closed his eyes—and saw before him the coal Kari had described, glowing, surrounded by snow. In his dream, he reached out to take it and felt the rough fingers of another grasping his own.

“Mine,” said a voice in his dream.

“Ours,” said another.

When he awoke, the hall was silent. The torches had burned down, and somewhere outside a strap creaked. He sat up, heard Einar breathing beside him, and smiled in the darkness. He knew, even before dawn in the east cast its first cold light upon the water's surface, that the night had brought them more than oaths.

And while the snow softened the roofs and adorned the posts outside with a delicate white rim, the same thin, bright layer settled on the three young hearts: a quiet seriousness, such as is felt before the first blow of a weapon; and beneath it the inexplicable, sweet burning that some call their own fire, others Yngvi's breath—and still others simply duty.

Outside, at Quernsteen, Count Eiriksson's red hair burst like flame from the collar of his cloak, and he gazed north, where the loading bay lay like a dark wedge in the white land. He inhaled deeply, and his mouth silently formed a word that no one heard: "Home."

In the hall, the salt fire rose as if taking a breath, then collapsed again. A small, glowing ember remained in the ashes, with an almost invisible heart of light. If someone had brushed the ashes away with a gossamer needle, it would have been clear that the ember needed both hands. Sometimes it's like that. Sometimes two boys and a girl carry something that the men will later claim for themselves.

But that is another story. For this night, it was enough that King Svein had sworn an oath, Valthjófr had given his word, the Icelander had shown his coal, and that Ketill Ravenhair and Einar Palnason, for the first time in a hall beneath a salt fire, felt something greater than laughter and longer than a sword.

In the morning, the falcon would sit on a post and raise its wings. And perhaps, if Astrid fed it in time, it would fly to where two boys were walking with a piece of coal inside.

CHAPTER II.

THE POST AT THE PORT.

Morning came like a silent enemy—first a cool breath, then a bright break on the horizon. Heiðabýr lay bathed in pale light, its roofs dusted with a light layer of snow, the harbor covered by a thin skin of ice that crackled close to the pilings whenever someone touched it with a boat hook. Below the warehouses, the first smoke was already rising from low kitchens; somewhere a voice called for caraway and fish, another for linen and hot water. Dogs ran across the planks, making them clatter like loose teeth.

Ketill was already standing by the post Einar had mentioned the evening before. It was an old harbor post, its wood scarred by deep, gray furrows carved by ropes. A shield, its bulge reflecting the sun, hung from it. Astrid arrived, her bow under her arm, her hair knotted at the nape of her neck, a fur draped over her shoulders from which the hem of a blue dress spilled. She wore no horn at her belt—Astrid drank only water in the morning; everyone in Heiðabýr knew this, and she accepted a bit of teasing for it.

"You're early," she said.

“I spent the night dreaming of falcons,” Ketill replied. “And you?”

“With dreams of men who don’t listen,” she said, putting down her quiver. “Where is Einar?”

"He's coming," said a voice, and there was Einar, bow in hand, mouth tight, eyes clear. "I still had to wake someone to count our fingers before we draw the strings."

"You mean the Icelander?" Ketill grumbled.

“I mean my conscience,” Einar said dryly. “And Kari has been awake since it got dark. I saw him in the shadows when I walked past the smithy.”

"He sleeps standing up," said Astrid. "Like a horse in a long winter."

“Are you ready?” a fourth voice chimed in, gruff and gleeful. Thori Longstep stumbled over a pile of dew, shuffled over to them, and dug his heels into the wooden plank. Behind him, two or three Jomsborg men appeared. Word spread quickly through Heiðabýr.

"Three arrows," said Astrid, as if she were in charge. "Whoever hits the hump twice wins. Whoever misses rinses their mouth with snow and remains silent."

“You make up rules so you can win,” said Ketill. “You shoot first, Astrid. So we know where not to aim.”

Astrid stepped forward, raised her bow, exhaled calmly, and her fingers brought the string to her cheek without the movement being visible. Her arrow flew—it didn't sing, it swept—and lodged in the middle of the iron boss, so that the shield tapped softly against the post like a heart.

"That was a coincidence," Thori murmured.

"That was practice," Einar said quietly.

Astrid didn't laugh, didn't stumble, nor did she do what some women might have done if men stared at her as if she were a marvel. She stepped back, nocked the second arrow, and released it—and it plucked the fletching of the first, barely a finger's width lower. Einar pursed his lips even thinner; he knew when a second shot was harder than nine.

“Your falcon is blind,” said Astrid, without turning around. “But your shield has eyes.”

“If you bet the third time,” said Ketill, “I will lose my falcon and my pride.”

“Your pride is tough,” said Astrid, “it won’t die. Your falcon, however, will.”

She nocked the third arrow. A light gust of wind swept across the ice, rattling the shields on the boat. Astrid's hair, which had fallen from its bun, brushed against her cheek. The arrow flew, a fraction to the left—grazing the edge of the hump, leaving a narrow mark on the iron, and burying itself in the wood.

"Too bad," said Thori. "The falcon lives."

“The falcon lives, even if I hit him,” Astrid replied. “If he’s smart.”

Ketill stepped forward. He didn't speak, and his smile vanished as he wrapped his fingers around the bowstring. It was clear he was now serious about the game. His first arrow hit the hump—not the center, but with a sound that was rich and full. The second flew a finger's breadth lower, ricocheted, and clattered across the deck. Voices rose; the men stopped what they were doing and looked over.

“If I manage to do one more,” said Ketill, without his gaze wavering, “my falcon will come with you, Astrid.”

"He will not walk with me," she said. "He will fly above me."

The third arrow flew – there was a sound, dry and hard, like someone tearing a piece of wood. The shield was struck from the side; the arrow ricocheted off the edge. A boat hook pulled the shield from the post.

“Hey!” shouted Thori, jumping forward. “Who’s playing games here?”

A figure stood by the post, the hook still in his hand. A face carved from wood—lumpy cheeks, a scar across his temple that looked old and malevolent. The man wasn't grinning; his teeth were fine, but they betrayed coldness. Two others stood behind him, their hands tucked under their coats.

"You have fine marksmen here," said the man. "Shooting at wood while other men should be looking at the ice. Northward. A ridge has risen between here and Helgeness. One of your ships, which sailed out during the night, is lying on it like a fish on a rock."

“Who are you?” asked Einar, and his voice was suddenly as harsh as his gaze.

“Me? An old plank in a new ship,” the man said. “I’m bringing the message as I received it. The man who sent it doesn’t have enough time to go into halls. He’s waiting for someone to take action.”

"Who sent you?" asked Ketill.

“Anyone with eyes can see,” the man said. “Jarl Valthjófr saw it. Hrafn Eiriksson saw it. And so did Thorgeir of Nordmøre.”

The last word hung in the frost as if it were alive. Einar felt something cold and something hot surge up in his chest at the same time. "Thorgeir..." he said, and the air cut him off.

“Thorgeir saw it,” the man continued, “because he’s standing at the wrong end. He’s in Hvall Bay by a fresh fire. Whoever finds him can warm themselves. Whoever doesn’t find him will freeze later. I’ve kept my word.”

He dropped the hook, turned around and left without counting the heads that watched him go.

“I know that fellow,” Thori grumbled. “He’s like a starfish: slippery and with more arms than you can see. His name is Runolf; he used to be a boatswain for a man from Lade. Now he sells news.”

“He sells both,” said Astrid, who had remained silent until now. “News and opponents. Whoever believes him believes the sea when it reflects its light.”

“Whatever he is,” said Ketill, “time is running out. Valthjófr won’t wait around like an old eel. We’re going down to the jetty. The falcon can wait.”

“The falcon has been waiting a long time,” Astrid said dryly, and a hint of a smile stole around her lips. “Go. I’ll come later when winter has left my hair behind.”

"You're not coming with us," Einar said immediately. "Not northwards."

“I haven’t decided yet,” said Astrid, picking up an arrow that was lying on the deck. “I’ll go wherever I go.”

“Be stubborn as a storm,” Ketill muttered. “But pull your skin tighter around your shoulders.”

They walked without turning around, and the men at the harbor understood from their pace that the games were over. Beneath their feet, the ice sang softly—a thin song—and amidst the shouts of the boatmen, something else could be heard: the click of small pieces of metal falling into sacks. In Heiðabýr, they called it: “Feeding the mouths of the axes.”

Valthjófr stood on the jetty, heavy in his coat, and Hrafn Eiriksson beside him, his red hair like a beacon in the winter light. Kari, the Icelander, stood a little apart; he gazed at the ice and closed his eyes now and then, as if listening, and repeated quiet words that no one heard.

“We’ll cross the sound when the sun rises,” said Valthjófr, as Einar and Ketill approached. “The oars stay under the skins until the first bay is behind us. Hrafn leads. Thori jumps first if we hit wood. Palnason—you hold on until you can’t anymore. Ravenhair—you listen to me and the ice. If either of them sings off-key, listen more closely.”

“Understood,” said Ketill.

“And I,” said Einar, without asking, without requesting, “will receive Thorgeir.”

Valthjófr looked at him—not for long, but long enough for Einar to feel the gaze pulling at him like a rope on a stake. “You’ll get him when you stand before him alive,” the Jarl said tersely. “Not sooner and not later. And you won’t run at him once we’ve tied you to the ropes. Do you understand?”

“I understand,” said Einar, and his mouth was suddenly dry.

"Good," said Valthjófr. "Men!" he then shouted, his voice flying across the gangplanks like a stone over water. "Pursue your blades, fill your shields, bind your knees. We do not go to feast. We go to find. Those who are light, stay here. Those who are heavy, come with us."

The men from Jomsborg laughed briefly – they were all heavy men – and boarded. The first fur sailed over a rowing trestle, and the soft creaking of an old block sounded like an old friend wishing you good morning.

Kari stepped beside Einar as he climbed onto the board. "You want Thorgeir," he said so quietly that the wind almost swallowed it.

“I want him,” said Einar.

"And what if you get him?" Kari asked.

“Then…” Einar began, and broke off. It was difficult to say “then.” “Then an old hole inside me is no longer empty.”

“Sometimes,” said Kari, “when you try to plug a hole, it only gets bigger.”

“You’re stuffing it with fake rags,” Einar snarled, turning away. He disliked the Icelander’s thin sentences, which crept into his ear like cold fog.

"If you fall," Kari added just as quietly behind him, "don't fall with too much in your hand. Otherwise you'll sink faster."

Einar didn't answer. He placed his hand on the stile and felt the rough, cold wood. The smell of pitch rose to his nostrils, and something like a mild intoxication set in—not from the ale he hadn't drunk, but from that old feeling when everything becomes light in a body because the decision to leave makes the body as thin as a blade.

Astrid was standing at the end of the jetty when the ship fired. She had the falcon on her arm, the hood pulled over her eyes. "Go," she said, not aloud, more as if speaking to herself. "Bring me back a name. Or yours."

The falcon moved its talons and snapped lightly at the glove. Astrid slipped the hood off the bird's head. The falcon blinked, shook its feathers once, raised its wings—and remained perched. "Clever creature," she murmured. "It doesn't fly when the ice is still singing."

CHAPTER III.

THE BAY OF HVALL.

The first light, which painted the fjords with a narrow, cold band along their edges, brought the raising and lowering of the oars. Hrafn Eiriksson stood at the bow of the first ship, boat hook in hand, pushing aside the thin ice where it had formed a veil across the bay. It crackled and broke, the shards leaping sideways like small fish. Behind him came Valthjófr's ship, and behind it the others.

First there was only the ice, then came the rocks, reddish and black, with plumes of snow in the crevices. Then boats—two, three—lay at an angle to the shore; at the edge of a low bay stood wooden shelters, like those found everywhere along the coast. No smoke rose. That was not a good sign; men who had fires usually liked to show that they had warmth in a cold world.

"They are there," Hrafn said softly. "They are just silent."

"I like silent opponents," Thori murmured. "They scream so beautifully when you find them."

“Keep your tongue in your mouth,” Valthjófr growled. “Raven’s hair – the edge.”

Ketill knelt and leaned his head so far over the edge that his cheek grew cold where the water breathed. He placed two fingers on the wood and listened. The wood gave him a song in return: a deep tone, calm, without that strange, hollow timbre that eddies impart to the hull when they lurk. He raised his hand. "It's clean," he said.

“What is clean,” Einar murmured, “can get dirty.”

“Everything can get dirty,” said Valthjófr. “Thori – take six men. Hrafn – hold behind the outermost row of stakes. If an arrow comes, I want to know where it came from. Kari – stand next to me if you’re already standing.”

"I am standing where I need to be," said the Icelander.

They went inside. It was like putting a tongue into a tooth that had been aching. Everything was where it seemed to be: posts with no fresh ropes hanging from them; a shed whose door stood half open; tracks in the snow—many—yet so scattered as to obscure rather than reveal. That's an art; men who want to fall run about in confusion. Men who want to hunt conceal their direction. Hrafn raised his hand—then an arrow flew, silently, with the old trick—from the side, not from the front. It landed with a dull thud in a shield. No one shouted. That was the second bad sign.

“Left,” said Hrafn, and his boat hook plunged into the shadows like a spear. A man staggered out, a short gasp, then Thori’s axe, so fast that its trajectory was invisible, only the result: the man sank, his hair spreading in the snow, dark.

“I know that,” Valthjófr said suddenly, and his voice changed. “That’s not a bay. That’s a mouth.”

Einar saw it now too: two hooks in the rock, ropes above them casting slings; at the edge of the row of stakes, dark, slender shadows, not stakes, but men in furs, motionless. And behind them – the shed, its door half-open, was wide and deep enough to accommodate a line of men standing with bows, drawn, breathing through their teeth, their sinews dry.

“Runolf,” Thori crunched. “Starfish. I’ll cut off your arms.”

“Later,” Valthjófr said. “Now get out. Retreat like a catfish. Slowly – backwards – don’t show that you know.”

They began to walk on as if nothing had happened—and yet they were walking back. It was an art to do that. Those who lived the longest could do it. Einar succeeded because Ketill was beside him, his hand resting unobtrusively on his arm, guiding him when his muscles yearned to move forward. Then, as if growing out of the ground, a man appeared before them—neither tall nor short—wearing a cap of wolf fur, and in his face lived two eyes that one never forgets once seen: hard, bright, and yet with that spark that some hate, others love—the light of a man who knows how to wait. Thorgeir of Nordmøre.

“Palnason,” he said, as if he saw an old acquaintance in a market. “Your chin is like your father’s. But you bite down less hard, from what I hear.”

Einar felt his body lurch forward, and at the same time felt Ketill's hand like a clamp, strong, unyielding. The world narrowed in his mind, became narrow. "Thorgeir," he said. Nothing more. Nothing less.

“You have his father’s mouth too,” Thorgeir said. “He saw me a day too early and a man too late. You will see both in their proper time.” He raised his chin slightly, as if nodding to someone behind Einar. “Now.”

The ropes fell. They came from both sides, quickly, with lead rings at the ends to make them heavy. It was an old fisherman's trick, applied to men. One of the Jomsborg men went backward as if someone had swept his legs out from under him. Hooks slid over shields.

“Right!” Valthjófr shouted, and his voice was neither loud nor high-pitched, but it cut through the noise like a knife through leather. “Off!”

They ducked, kicked, tore, and cut. The first arrows flew now, and the air took on that thin, sharp sound only an arrow makes when passing close. Thori leaped, as his name suggested, and was suddenly there where just moments before there had been a shadow. A man screamed. A second gnashed his teeth; it's a different sound than teeth grinding together as an axe plunges into the back. Einar saw Thorgeir, and Thorgeir saw him, and for a long moment—or a short one—time stood still and yet moved on.

“Come,” said Thorgeir, and there was strangely little mockery in his voice. “Not now. Not here. You’ll regret it if you do it now.”

“I haven’t regretted anything for years,” Einar said, and the statement surprised even him. He jumped—but he didn’t. Ketill’s hand held him, like one holds a dog that has walked into a trap containing a bear.

"Einar!" growled the raven-haired man. "Not now."

"When then?" Einar snarled.

"If you're not dead," said Ketill.

It wasn't elegant. It wasn't grand. But it was right. Einar stepped back, cutting the rope that had wound around one of the men's arms. Beside him, he heard Hrafn's short, deep shout, the kind only men who spend a lot of time in boats understand—the other long stroke of the oars, not the same, with a hint of delay, that turns the boat. The vessel did indeed turn, the rest of the motion transmitted out into this bay, which was a mouth. "Out!" Valthjófr said again. "Out."

They made it. Not all of them. One of the men remained lying there; his fur turned dark. Kari suddenly stood beside him, where he hadn't been just moments before, and his face was strangely expressionless—like a lake whose surface is still, though it harbors eight fish in its depths. He bent down, took hold of the dying man's hair, the way mothers sometimes hold their sons' heads—and whispered something no one understood. Then he was gone again, so still, as if the wind had lifted him up. Einar glanced back—and saw that Thorgeir was gone. Like fish disappear when you put your hand in the water: one moment there, the next only ribs and light.

On the open water, the ropes came loose from the edges of the ships, the ice broke under the bows, the sound of wood and water mingled, and the first breath the men breathed freely sounded as if they had been silent for too long.

“Runolf,” Thori said gaspingly, “when I see you, I’ll hang you up by your own arms.”

“Do that later,” Valthjófr growled. He looked north, where the fjord opened like a narrow mouth, and then south. “Back. We’ve seen what we needed to see. The mouth isn’t closed. Not yet. But it’s snapping. And it has names in its teeth.”

“Thorgeir,” Einar said in a vacant voice.

“Yes,” said Valthjófr.

“He saw me,” said Einar, “and I saw him.”

"This is a start," Ketill said quietly. "It's nothing more. But it's also nothing less."

CHAPTER IV.

THE NIGHT BEFORE DEPARTURE.

Heiðabýr took the men back, as a great dog takes its master back at the door: with growling benevolence, with tongue and teeth. The hall filled up in the evening, but there was no great feast. The king did not speak of the salt fire, nor of the vow of the previous day; he looked Valthjófr in the eye and nodded. That was all.

Astrid stood to the side, and when Einar entered, she went to him and, without a word, placed her hand on his cheek. Her fingertips were cold. Einar held her firmly.

"You are whole," she said.

“No,” said Einar, “but enough to go.”

"I want a name," said Astrid. "Bring it to me."

“Yours or mine?” Einar asked, without smiling.

“One that’s spoken in halls,” she said, and her voice trailed off. “Not just in the chamber. Bring it to me so I can taste it.”

“I will bring it to you,” said Einar.

Ketill stood nearby, his back against a post, watching the two of them. Kari approached him; his face was in shadow.

“Raven hair,” he said, “you can’t carry two fires in one hand without getting burned.”

“I only have one,” said Ketill.

“You are carrying Einar with you,” said Kari.

“I wear what I have to wear,” said Ketill. “That’s because I’m a friend.”

"That's because you're a man," said Kari, and his mouth moved as if a second word wanted to follow, but didn't come.

“Eat!” Thori shouted from the other side of the fire, waving a piece of meat. “Tomorrow we’ll only have what the sea gives us. And if it gives us something, it wants something in return.”

Einar ate. He could hardly taste anything. The smoke in the hall, the noise, the muffled clinking of cups—everything seemed to be behind him, even though he was right in the middle of it. As he sat down, he felt the weariness in his body; it came suddenly, like a man stepping out of a door that cannot be bypassed. He lay down on the bench as he had the night before, the furs swallowing his breath.

He dreamed, and in his dream the post by the harbor was there again, and the shield, and the falcon. The falcon wasn't sitting on the post; it was sitting on Thorgeir's arm. "That's not your bird," Einar said in the dream.

“No bird belongs to a man,” said Thorgeir. “Only the one who feeds it.”

“I feed him,” said Einar.

"With what?" asked Thorgeir.

“By name,” Einar said, and then he awoke with a start, realizing he had said it aloud. Ketill lay beside him, breathing calmly, as men breathe who have done enough to sleep. Einar sat up; in the dim light he could see the outline of the hall—posts, hides, shield bands. Someone was snoring softly; another was murmuring in his sleep. A figure stood in shadow at the edge—Astrid.

“I couldn’t sleep,” she said when she heard him move. “I thought – maybe you can’t sleep either.”

“I thought I was asleep,” said Einar.

“You’re always thinking,” she said, and it wasn’t a reproach; more of a statement, like saying, “It’s snowing.” She came closer. “Einar—” She hesitated slightly; Einar saw her hand, which had been still just a moment before, open and close as if holding something and then letting go. “If you leave tomorrow—”

"I'm leaving," he said.

“Yes,” she said. “Then…” She paused. “Then look after Ketill.”

Einar blinked.

"He's looking out for you," she said quickly. "Always. I want someone to look out for him."

“I will,” Einar said. It was the only promise he could make without lying.

“And if you see Thorgeir,” said Astrid, her voice softening, “then—” She paused. “Then listen to your father’s voice, not your heart. Sometimes the heart sounds like a storm horn. And sometimes it’s a liar.”

“My father didn’t lie,” said Einar.

“No,” said Astrid. “He didn’t lie. That’s why he died.”

She turned and left. Einar remained seated until the dim light behind the cracks in the hall wall brightened. Then he stood up, took his cloak and belt with the short knife—he liked short knives; long swords had a certain dignity, but short knives were honest. Ketill stood too, in a single fluid, silent movement, like a wave that rises and then recedes. They looked at each other and nodded. Words would have been too much in this moment.

Outside it was morning, and the falcon sat on the post. He raised his wings as they passed and jumped up; he did not fly away, he flew ahead of them, lower than the day before, and perched on a rope by the jetty.

“Clever animal,” said Astrid, who was walking behind them. “He knows where he doesn’t need to fly.”

“He knows where I need to go,” Einar said, his voice so calm that he was surprised. “And I know where I want to go.”

“That’s rare,” said Kari, who had suddenly appeared beside them as if he had come out of thin air. “Whoever knows both will arrive. Or they won’t come back.”

“Both are arrivals,” said Ketill.

“Both are arrivals,” Kari repeated, his mouth forming a thin smile. “One with a body, the other without.”

"Start on it, Icelander," Thori grumbled from the boat. "You'll end up a priest. And then I'll have to listen to you die."

“Everyone listens when someone is dying,” Kari said. “But hardly anyone listens when someone is living.” He pulled his hood over his head and jumped on board.

The ships pushed off, the oars dipped in, the ice crackled, and a thin breeze from the sea carried the scent of salt and something else—something metallic that Einar couldn't name. Perhaps it was only his own blood he felt, the emptiness inside him yearning to be filled. Perhaps it was an omen. The Northmen loved omens when they were like arrows—straight, sharp, easy to read. This one wasn't. It was like the coal Kari had spoken of: it glowed, but you only saw it when you looked, and then you couldn't look away.

Heiðabýr grew smaller and smaller behind them. In the hall, the queen knelt before a cross fashioned from two beams and placed her hands on the crossbeam as if it were a board on which to count waves. King Svein sat on the high seat, his gaze fixed on a point no one could see—perhaps the west, perhaps an image in his mind. Astrid stood on the jetty, the falcon on her arm, the air flushing her cheeks. She watched the ships until they were nothing but dark lines, and then again when they were nothing at all. She stayed until the falcon's fingers nudged her, reminding her of water. Then, without turning her head, she returned to the hall, where she intended to wash her hands in water that smelled of salt.

And the coal – that small, glowing ember – lay somewhere in a belly, in a hand, in a glance. And it burned in such a way that it couldn't be seen. Not yet. But soon. Very soon.

CHAPTER V.

THE CRACK IN THE ICE.

The wind shifted to the northeast and increased in sharpness without carrying any waves—a knife-edge wind that watered the eyes and tore the skin on the ankles. The ships kept close to the low shoreline, which ran alongside them in a dark band. Hrafn Eiriksson had replaced the boathook with a spear, its iron flat and with a series of fine notches around the edge—a tool for pushing ice, not for stabbing people.