Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

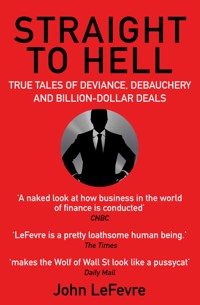

Over the past three years, the notorious @GSElevator Twitter feed has offered a hilarious, shamelessly voyeuristic look into the real world of international finance. Hundreds of thousands followed the account, Goldman Sachs launched an internal investigation, and when the true identity of the man behind it all was revealed, it created a national media sensation - but that's only part of the story. Where @GSElevator captured the essence of the banking elite with curated jokes and submissions overheard by readers, Straight to Hell adds John LeFevre's own story - an unapologetic and darkly funny account of a career as a globe-conquering investment banker spanning New York, London, and Hong Kong. Straight to Hell pulls back the curtain on a world that is both hated and envied, taking readers from the trading floors and roadshows to private planes and after-hours overindulgence. Full of shocking lawlessness, boyish antics, and win-at-all-costs schemes, this is the definitive take on the deviant, dysfunctional, and absolutely excessive world of finance.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 386

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in the United States of America in 2015 by Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Inc.

Copyright © John LeFevre, 2015

The moral right of John LeFevre to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade Paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 554 8

E-book ISBN 978 1 61185 965 2

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press, UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

To my wife and children. I wrote this for you, on the condition that you never read it.

Contents

Windows on the World

A Felonious Mentality

Ode to Liar’s Poker

The Parental Visit

The Handover

I’ll Call You on Your Cell

Networking

Carpet or Cock

The Roadshow

The Wild Wild East

The Lunch Break

The Warren Buffett of Shanghai

Bluetooth

The Stakeout

Princelings and Dumplings

The First Day of School

Because They Are Muppets

The Minibar

Conference Call Etiquette

Letting the Bad Out

A Long Day

Making It Rain

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Author’s Note

“Goldman fucking Sachs. Ever heard of it?”

It was the perfect inaugural tweet. Ever heard of it? is such a common (and irritating) banker phrase that it had become its own joke, like when one banker says, “Nice tie. Brooks Brothers?” and the other banker dismisses him with, “Charvet. Ever heard of it?” I’ve always made fun of this mentality by adding “Ever heard of it?” after any kind of shameless place or name-dropping.

Just a few hours earlier, I had been in a bar in Hong Kong with a group of friends, all of whom were finance guys. Although markets had recovered from the bowels of the financial crisis, the summer of 2011 was still a tumultuous time.

The Occupy movement was just starting to gain momentum; people were still angry. Despite the housing collapse, the ensuing crisis, and subsequent bailouts, not a single banker had been held criminally responsible. Bonuses had remained relatively intact and the equity markets had come roaring back from the lows of 2009. The fact that most people hadn’t benefited from the market recovery, and that income inequality was breaking through generational highs, only further fanned the flames of anger and resentment. One friend of mine joked about how his wife had been nearly heckled out of a Manhattan doctor’s office after being overheard telling the receptionist that their insurance was provided by Goldman Sachs. Anti–Wall Street sentiment was rampant. “Fucking plebes.”

Earlier that day, I had seen a Daily Mail story about an anonymous Twitter account (@CondeElevator) that hilariously chronicled the most ridiculous conversations overheard in the elevators of the infamous Condé Nast building. Holy shit, I thought. If people are so intrigued by this kind of banality, I cannot imagine what they would think if they heard the outrageous things bankers say and do. Despite all of the vilification and negative attention, most people still had no idea what Wall Street culture was really like.In the drunken haze of that subsequent evening, @GSElevator was born—“Things heard in the Goldman Sachs elevators do not stay in the Goldman Sachs elevators. Email me what you hear.” The premise was simple—to illuminate Wall Street culture in an entertaining and insightful way.

I chose Goldman Sachs because of their position as public enemy #1, and people’s fascination with “vampire squids” and the absurdity of Lloyd Blankfein claiming to be “doing God’s work.” More specifically, in having recently gone through the arduous process of being offered the prestigious job of Head of Asia Debt Syndicate at Goldman Sachs (a hiring that was deemed newsworthy by Bloomberg and others), I found their culture to be an amplified version of broader banking culture. I kept the construct of elevators simply as an homage to the original Condé Naste feed, but made it clear that it was never literally about conversations overheard in elevators at Goldman Sachs.

Over the days that followed, I got mentions in the the Daily Mail, on Gawker, at ZeroHedge, in the New York Post, and elsewhere. I had friends calling and accusing me of being the source, or culprit, depending on their point of view. I had other friends being accused themselves. I even had an ex-girlfriend (the Warden) telling anyone who would listen that it was me. All of a sudden, a silly, drunken, inside joke had run out of control, jeopardizing my identity and my livelihood and threatening to impact me and my friends.

So when the New York Times reached out asking for an interview, of course I lied to them. Because, who gives a fuck? It was a bullshit Twitter account with 2,000 followers. More important, my personal details were irrelevant. @GSElevator is not even a real person; it’s the concentrated reflection of a culture and a mentality, the aggregation of “every banker.” Getting focused on me the person misses the point. More to the point, as a “submit what you hear” platform, @GSElevator does work at Goldman Sachs, and JPMorgan, and Morgan Stanley, and everywhere else. But who gives a shit? What mattered more was that the authenticity of my voice ruffled feathers and captivated people around the world and across the spectrum.

I had no idea where the Twitter account would take me, but I did know that I had been collecting stories (the inane and insane) over the course of my career in banking. I joined the fixed-income desk of Salomon Brothers immediately out of college.* Starting in the wake of the dot-com bubble bursting and working through the financial crisis, across three continents, I enjoyed a colorful career during a turbulent and defining period in the history of financial markets and our society in general.

As “one of the most prolific syndicate managers in Asia,” I saw it all. I worked intimately with investment banking and sales and trading, corporate and sovereign clients, and asset managers and hedge funds. I did deals with every bank on Wall Street—directing traffic at Wall Street’s epicenter: the bond syndicate desk.

Once I left Hong Kong, I was less worried about my identity coming out. I started tweeting about specific details and events that made my identity obvious to a large number of people within the capital markets community. I wasn’t subtle—in an article I wrote for Business Insider, I recommended a haircut by Sammy at the Mandarin Oriental in Hong Kong. He’s so old and shaky that it had always been a running joke of mine to send visiting colleagues his way for a straight-razor shave.

Once I made the decision to write a book, I knew that my identity wouldn’t remain the terribly kept secret that it was. In fact, I was counting on it. Revealing myself was the only way for me to speak candidly and credibly about the vantage point from which I have observed and enjoyed my outrageous experiences.

This book isn’t an indictment of any particular firm, some kind of exposé, or a moralistic tale of redemption. Rather, my objective is to unapologetically showcase the true soul of Wall Street in a way that hasn’t been done before. No epiphanies. No apologies. No fucks given.

Many of the names, some of the characteristics and descriptions of people, and other minor details have been changed in order to protect people’s identities. It’s not my intention to be mean-spirited or inadvertently impact people’s careers or personal lives, and many of the people mentioned in this book are still my close friends to this day. As it relates to the people I don’t give a shit about, fortunately for them, the lawyers made me change those names too.

Windows on the World

“Excuse me, another round of Bloodys, please?”

It’s August 2001, and I’m hanging out at Windows on the World, at the top of Tower One of the World Trade Center, with a few of my fellow new analyst classmates. It’s only 9:30 a.m., but we don’t really care. Most of my drinking companions are either European or well connected; everyone else is far too cautious to skip out on training. They’re all across the street in the auditorium of 7 World Trade, diligently taking notes about financial accounting, bond math, or whatever.

I’m not worried about skipping class; I was there first thing to put my name on the sign-in sheet, and I’ve got a promise from a friendly classmate that he’ll text me if there’s any kind of impromptu roll call. So far, that text hasn’t come, but I keep a pack of Marlboro Lights in my pocket just in case I need an alibi for the time it takes me to make it down two elevators and back across the street.

Besides, it should be time to celebrate. We’ve made it. Wall Street, the pinnacle, some might argue, for any ambitious and accomplished college graduate looking to enter the workforce. I don’t recall the precise statistics, but we’re reminded on a daily basis how fortunate we are—the firm received something like 25,000 applications for roughly 350 spots globally.

Gazing out the window on the 107th floor, I feel confident, even invincible. It wasn’t always that way. During my interview with Lazard Frères, a prestigious boutique investment bank and one of the last true partnerships on Wall Street, I almost passed out from vertigo staring out the window from the mere fifty-seventh floor of 30 Rockefeller Plaza. Then, after a final-round interview superday with Bear Stearns, I inadvertently sent a thank-you email to the head of emerging markets, telling him how much I wanted to work for JPMorgan. During a Goldman Sachs interview, some asshole asked me who, living or dead, I would most like to have dinner with. I guess he wasn’t particularly impressed that I named Tupac Shakur ahead of Marcus Aurelius or Alexander Hamilton. Still, despite these hiccups, in the end, I wanted to do fixed income, and for that, there was arguably no better place to be than Salomon Brothers, with the recently added platform and balance sheet of Citigroup behind it.

There’s only one slight problem: my analyst class is the largest in the history of investment banking. We were hired based on quotas set in mid-2000, before it was evident that the dot-com party was over. Nowhere is this more painfully clear than in the European TMT team (telecom, media, and technology), which hired forty first-year analysts. On the first day of training, those analysts were informed that there were now only seven available spots, leaving them scrambling to find a new team before the end of training or be out of a job.

With the exception on TMT, most analysts aren’t assigned or invited to join a specific team until near the end of training. Having received an offer after my internship in debt capital markets the previous summer, I already know I have a bid from that group if I want it. But for most of the analysts, the real competition is just beginning. It turns out that landing a coveted Wall Street job isn’t the finish line; it’s the starting block. You wouldn’t know it looking at the flushed faces around our table at Windows on the World, surrounded by Brooklyn Lager empties and half-chewed celery sticks.

Later that afternoon, we are given the first of many ominous warnings.

“Let this be a reminder to all of you. Not only are you required to attend all training sessions, you are expected to act in a professional manner and take them seriously. Additionally, next Tuesday, we will have our first exam—accounting. In all likelihood, the bottom 10% will be let go.”

A posh-sounding British kid, one of my drinking buddies, raises his hand. “But I studied classics at Oxford? This doesn’t seem fair.” Apparently, it’s not all shits and giggles.

“What do you think the training is for? I’m sure you’ll do fine.”

This doesn’t faze me at all; I studied finance and economics. Other than learning how to use Excel without a mouse, I don’t really need the training.

It turns out that HR is not bluffing. The day after the first exam, the results are posted on two large bulletin boards in the back of the auditorium. In a lazy attempt at privacy, one board lists each person’s name along with a random numerical code next to it. The second board has each person’s code listed in numerical order with their exam result next to it.

Obviously, the first thing everybody does is look up their own scores—I passed with flying colors. After that, we all spend the next ten minutes indiscreetly running back and forth between the two boards gossiping and checking the results of our friends and adversaries. HR makes no attempt to provide summary statistics or clarity on the results, leaving those who had not fared well to fester in uncertainty while awaiting formal confirmation of their fate. That night, the bottom 10% is notified with a simple note under the door of their temporary corporate housing apartments. We are all a bit envious of the people who no longer have a roommate.

There’s a certain nonchalance and indifference about the firm’s approach to this process that we all find both disconcerting and thrilling. The next week, it happens again after the financial math exam. Same drill—the bottom 10% is let go. Again, I have nothing to worry about. There’s blood in the water now, and I have to admit, the process is somewhat exhilarating.

I do feel bad for some of these kids. I just hope they saved their Barneys receipts. Pathetically, one kid even tries selling his new watch before he leaves town. But what the fuck am I going to do with a Movado?

With the exams out of the way, and the deadweight gone, everything settles down as the emphasis of training shifts to things like PowerPoint, Excel, financial modeling, and presentation skills. We are each assigned a cubicle on a spare floor in 7 World Trade to work on group projects and individual homework assignments.

The homework assignments are a joke. Five minutes before class, I’ll jump on my computer, go to the shared drive, and find a copy of someone else’s completed assignment. With a name change and a quick scan of the document to make sure the answers are sensible, I print it out and head off to class. Many of the kids in my class, particularly the ones I associate with, do this as well.

One day, our HR point person steps up in front of us in the auditorium. “I’d just like to inform you that we’ve had to let go eight of your classmates for copying homework assignments.”

A few of my classmates—many of whom wouldn’t last—look at each other, appalled that anyone could be capable of cheating, while the rest of us look at each other in relief that we hadn’t also been caught, highlighting the age-old battle between the front-of-the-class and the back-of-the-class mentalities.

From that day forward, I am more careful. Instead of five minutes before class, I’ll come in ten minutes early. Then I’ll add my own personal touch on the formatting, rephrase some of the answers, and even make a couple of intentionally unique mistakes.

Again, within a week, four more people are fired for stealing homework. This time, it turns out that some of our more spiteful classmates had started sabotaging files in the drive, even creating fake files with all incorrect answers. As we see it, if you’re dumb enough to get caught cheating, you probably don’t belong on Wall Street.

We celebrate by skipping training the following day for a liquid breakfast up in the sky followed by lunch at Peter Luger.

After that, things start to settle down again. HR reassures us that, barring any further disciplinary issues, all the cuts have been made. The rest of training is spent rather uneventfully in the auditorium or, for a select group of us, across the street. Our evenings are spent doing team-building exercises, bowling at Lucky Strike, and getting drunk on Hudson River cruises. I’m not one for name tags and meet and greets, but there is certainly a business case to be made for getting to know all the kids in my class.

For the final day of training, the firm puts on a celebratory pep rally in the auditorium of 388 Greenwich Street. Bigwigs like Mark Simonian (global head of TMT), Sir Deryck Maughan (chairman and former CEO of Salomon Brothers), Michael Klein (head of investment banking), and Tom Maheras (head of fixed income) each deliver rousing speeches about how there’s no firm in the world they’d rather work for and no better place for us to start our careers.

Now we feel like we’ve made it—all 272 of us who remain. Having arrived late, I’m stuck in the back with a middle seat that will make it impossible to slip out unnoticed. Shortly after we begin, a kid I sort of know a few rows in front of me gets up and tries to make an exit. Man, he’s got balls. Mid-speech, he’s shuffling across, forcing people to stand up in order to make way for him to pass.

“Excuse me. Sorry. Pardon me.” It’s like being in a movie theater except that the room is fully lit, and he’s interrupting a Master of the Universe who is busy onstage talking about his favorite thing—himself.

Ten minutes later, the kid walks back down the aisle of the auditorium. This time, he looks red-faced and teary-eyed. “Excuse. Sorry. Pardon me,” he repeats over and over as he makes his way back to his seat. Holy shit, did his mom just die? What the fuck happened? Once he gets to his seat, instead of sitting, he reaches down, grabs his signature Salomon Smith Barney blue-and-green canvas duffel bag, and turns back around. His blotchy red face turns completely scarlet and the puffy eyes unload a waterfall of tears. “Excuse me. Sorry. Pard—ah—ah uh ah uh.” He can’t even get the words out without whimpering. His efforts to muffle the sound of his sobbing almost make him hyperventilate. It’s disgusting. And then, just like that, he’s gone.

Meanwhile, onstage, Sir Deryck Maughan is wrapping up his speech. “Congratulations on being a member of the analyst class of 2001, the most qualified class in our storied history.”

Five minutes later, another analyst gets up and walks out. A few minutes pass, and then she comes back, collects her purse and canvas bag, and leaves, looking rather more stoic than the first guy, but still stunned. Now a few people in the back are starting to suspect something is quite obviously wrong. As she walks out, from my vantage point, I can see her mouth to a friend, “I just got fired.” Most people from the middle of the room forward are still unaware of what’s happening behind them.

Five minutes later, another guy gets up and starts to walk out. He doesn’t appear to realize that he’s about to get shit-canned. Someone from the back shouts out, “Dude, just bring your stuff with you,” which is good for more than a few laughs.

Finally, between the disruption and the whispers working their way around the room, people start to figure out what’s happening. An Asian girl sitting next to me, whom I had never spoken to before, says, “Shit. I got a notice under my door to see HR this morning at ten fifteen a.m. That’s in ten minutes. I assumed it was regarding the team I would be assigned to. But clearly not.” And with that, she gets up, says, “It’s been real, y’all,” to no one in particular, and walks out.

Confirmation of the news, and the meaning of the HR notices, has now spread across the entire analyst class. At this point, all the people who had received an HR notice get up and start walking out.

Back onstage, Michael Klein doesn’t skip a beat. He assures us that we can all be just like him one day.

I later find out that the first kid who got fired begged HR to go back into the auditorium to collect his bag for him and spare him the tearful walk of shame. They refused. No worries; I hear he’s a successful broker now.

A Felonious Mentality

“You may have escaped from this situation unscathed, but in my eyes, you are nothing but a weasel.” My adviser, Mr. Cobb, has just burst into my dorm room to share this uplifting gem with me.

He looks at me (my head studiously buried in a textbook), glances over at my stereo (classical music playing softly), and then just rolls his eyes. Had I not been fourteen years old, he probably would have made the jerk-off hand motion.

In all fairness, his presumption isn’t too far off. Just two minutes earlier, I had recognized the sound of his not insubstantial weight coming up the stairs, quickly turned off the game of Maelstrom I was playing on my McIntosh, flipped open my chemistry book, and switched from Dr. Dre’s The Chronic to the Vivaldi’s Four Seasons CD I stole from my mom.

“Mr. Cobb, coming from you, I think I’ll take that as a compliment.”

Fuck him. As my fourth form (tenth grade) adviser, he’s supposed to be my ally, my father figure away from home, the guy in my corner, and a guiding presence during these crucial, character-building early teenage years. Instead, he has looked for every opportunity to pick me off. And at this point, there’s nothing I can do to change his opinion of me.

I’ve just experienced my first major run-in with the Choate Rosemary Hall authorities. Coming back from class a few days earlier, I had decided to grab a seat in the dormitory common room and hang out with some friends. The chair I chose immediately collapsed from my rather underwhelming weight. I looked down to discover that someone had broken off the leg and then reattached it in a way that made it appear structurally sound; it was a booby trap.

Admittedly, my reaction was rather juvenile. I picked up the chair and repeatedly smashed it into the ground until it splintered and broke apart, leaving the room strewn with shards of jagged wood and pieces of foamy cushion.

That night, at our weekly dorm meeting, our housemaster, Mr. Gadua (whom we had nicknamed “The Gimp”), inquired about the broken chair. “I need the person who broke the chair to come forward.” Of course, no one said a word.

The next day, I received a meeting request from my dean; someone must have ratted me out. I’m getting sent before the judicial committee. Not only am I facing a charge for breaking the chair, I’m also accused of a much more serious honor code violation for lying to The Gimp. Boarding schools tend to get sanctimonious and self-righteous when it comes to issues of honor.

My first instinct was to argue that I broke the chair in order to prevent other people from being injured. But that wouldn’t absolve me from the honor code violation. So I decided to keep my argument simple. “In my mind, as it relates to a chair, it is impossible to break something that is already broken. So when The Gimp asked us about the chair, I did not step forward, because I genuinely do not know who broke the chair.” Case dismissed.

Even at this impressionable age, I knew that I wanted to go to Wall Street. I had never really enjoyed obeying authority figures, especially the idiotic ones like Mr. Cobb or The Gimp. Besides the influence of watching the movie Wall Street on basic cable and reading Liar’s Poker (and then Den of Thieves, The Predator’s Ball, and Barbarians at the Gate), my fascination with Wall Street really crystallized during my first year at boarding school. I became captivated by financial markets, the men who mastered them, and the tangible benefits that came with it.

This was only reinforced when all the parents came down from places like Greenwich for parents’ weekend. The Wall Street dads were the cool dads with the sports cars and a propensity for profanity. They’d tell our dean we were spending the weekend with them in Connecticut, only to let us disappear into New York City, where we’d take down a suite at the Waldorf Astoria and use the concierge desk to get us into places like Scores and Au Bar. This is when I internalized the number one rule of life: “Rules are for the obedience of fools and the guidance of wise men.”

From my experience, Wall Street generally attracts people with a certain mentality. It then takes those people, breaks them down, and molds them to suit its singular purpose—making money. Priorities are relative. Concepts of wealth are relative. Expectations and standards of hard work and intelligence are relative. Morality and deviance are relative. Wall Street operates in its own reality. Assimilate or die.

In its own way, boarding school was great preparation for investment banking. Not only were the Wall Street dads different, so were their kids. They had a much more evolved perspective, at a much earlier age, than the rest of us—a certain confidence, a kill-or-be-killed mind-set, even a felonious streak when it came to authority. They were the kids in the dorms who somehow managed to get a doctor’s note that allowed them to have a refrigerator in their room. (It turns out every investment banker knows at least one doctor who owes him a favor. Where else were we supposed to get the Ritalin?) Their parents not only let them break rules they didn’t think should apply to them, but encouraged and abetted them. Boarding students can’t have cars on campus? No problem, just keep it in the parking lot at the public library in town. Students aren’t allowed to have cell phones (it’s the mid-1990s)? Be smart; just don’t get caught. Let scholarship kids, or worse, do-gooder types follow the rules. Then come talk to me in twenty years.

They make little attempt to operate within the framework of a “meritocracy” unless it suits them. Can’t break 1300 on the SATs because you’re a moron? No problem. Get diagnosed “learning disabled” and then take all standardized tests untimed. One friend and classmate got an 1100 on his SATs, which, despite his being a legacy applicant, obviously wasn’t going to get him into Penn. A doctor’s note later, he was retaking the test untimed. Instead of spending four hours in a gymnasium with strict proctors looming over him like the rest of us, he had an entire week in a private classroom with minimal supervision, allowing him to covertly save vocabulary words, analogies, and math problems in his TI-82 calculator so that he could correct any mistakes the following day. A 1400 on the retake, which is still embarrassing under the circumstances—that’s like only netting $50K on a an insider trading scheme—got him off the Penn wait list, and now he works for a hedge fund in London and drives a Ferrari. Granted, he bought it used for less than the price of a BMW 5-series and works in a mid-office capacity, but none of that registers with his Facebook friends. He was born on third base and scored on a wild pitch, but at least he can convince his friends (and himself) that he hit a triple and stole home. The ends justify the means; that’s an important concept to understand if you want to be successful on Wall Street, and is one that boarding school taught me well.

Being a young, naive kid from Texas, it took some time for me to grasp this mentality, but I caught up pretty quickly. By junior year, I was the one with the Sega Genesis and TV hidden in my closet on top of my minifridge.

I also learned other key trading-floor skills: bullying, hazing, and the art of a great prank. One night, a kid who lives across the hall from me leaves his room to go take a shower; he’s one of these dopes who showers at night right before lights-out in order to save time in the morning.

Shower pranks are fairly standard. Someone will steal their towel, or lock them out of their own room, or both. That’s boring. It’s happened to this kid so many times that he practically showers with one hand on his towel.

Knowing that we are both studying for the same calculus exam at 8 a.m. the next morning, I go into his room, take his calculus textbook and binder full of notes, stuff them into his closet, and then lock the closet door by looping his Kryptonite bicycle lock through the door handles and leaving the key inside.

Then, for good measure, I also lock him out of his room.

He thinks that’s the joke—that someone has locked him out of his room while he was in the shower. No big deal. He walks downstairs in his towel and asks the housemaster to come up and let him in using the master key.

It’s only about fifteen minutes later, presumably when he sits down to study, that he realizes that his books are missing and there’s a Kryptonite lock on his closet.

Now he has to go back downstairs and explain the situation to our housemaster, who has to call campus security, which then has to summon someone from the maintenance department to come up and physically saw off his closet door, a process that eats up two hours of prime study time.

Although they had their suspicions, no one was ever able to determine who the culprit/mastermind was. I’m pretty sure I beat him on that calculus test. My transformation from a young, naive kid from Texas was coming along.

I was usually on some form of restriction or probation, and always under a cloud of suspicion. But I was developing an appreciation for absurdity and an ability to adapt quickly to the situation at hand. The two come together one memorable spring weekend afternoon. I am sitting in my room, which faces away from the quad and out across the parking lot to the junior varsity tennis courts. The parking lot is surprisingly full, as are each of the courts, with players and spectators. There are more parents than on a typical boarding school sports Saturday, which means it’s a home match against a nearby day school.

I’m a decent tennis player, but I never bothered playing in school. Being on the golf team was way more fun. With a dozen or so guys and only one coach, it was impossible for him to supervise all of us. Along with a few friends, our objective was always to play well enough to make the team and then never well enough to qualify for the top seven who would travel on match day for the tournaments.

A few times a week, we’d bus over to the Farms Country Club and play nine holes. Coach DeMarco would watch everyone tee off and then play his way up through each pairing so that he could watch and assess all of us fairly. We always made sure to be among the last few groups off the tee. Once our coach played a hole with us, we had six or seven uninterrupted holes to drink the beers we had stashed in our golf bags—and then throw the empties away on the eighthhole.

So here I am idling in my room having intentionally missed the golf tournament. For whatever reason, I decide to amuse myself by placing my speakers facing out my open windows and in the direction of the tennis courts. Snoop Dogg’s Doggystyle. Track 7. Volume up. Play.

Snoop kicks off “Lodi Dodi” with a gentle reminder to his detractors that they are welcome to fellate him. The sound is felt and heard with immediate effect. Most of the spectators instantly turn and face the dormitories looking for the source of the disruption. I crank up the volume almost to the point of blowing my Kenwood speakers.

All match play soon grinds to a halt; I’m not sure if it’s because the music is so distracting, or if they simply can’t hear each other recite the score. That’s when I see the tennis coach, Mr. Goodyear, frantically scanning the windows. This guy is so stiff that he wears bow ties on weekends. He drops his clipboard and breaks into a full sprint toward the dorm complex.

Fuck. What I’ve just done is petulant, immature, and, worst of all, indefensible in its stupidity. I probably only have about thirty seconds to figure a way out of this.

I dive away from the windows, strip naked, grab my towel, and sprint out and down the hallway toward the showers, leaving the music blaring and making sure to lock my door on my way out. I stay in the shower long enough for my heart rate to normalize, and then dry off and head back to my room.

Mr. Bowtie waits at my door. He’s hounding one of the security guys, who is fumbling through his massive key chain trying to find the master key for our dorm. Goodyear sees me coming toward them and screams, “Is this your room? Open the damn door.”

“It’s not locked. I never lock my door.” I’m cool and relaxed. With the speakers facing out the window, we can hear each other perfectly, although the walls and floors are shaking like we’re backstage at a concert. As soon as they get in, Goodyear goes right for the plug.

I’m quick to point out that this has all the markings of an ill-conceived prank—someone has clearly taken advantage of the fact that I trustingly left my door unlocked while I was in the shower. “I don’t know who could’ve done this, but everyone pranks everyone around here.” Bowtie slinks off disappointed; he’ll have to wait another day to bring me down. Unbelievably, the security guy winks at me; he knows who’s boss.

One of my most important life lessons came senior year: Two different English teachers have tasked my housemate and me with the identical essay assignment on Beowulf. What starts out as innocent and sincere brainstorming quickly escalates to us staring over a laptop crystallizing our ideas together. We sit there for the next couple of hours, casually talking and taking turns typing. The end result is phenomenal.

A week later, I get another summons from my dean; once again, I’m being sent before the judicial committee, this time charged with cheating, an offense punishable by suspension. If you get suspended during your senior year, you have to inform the colleges that you’re applying to—basically I’m fucked.

The verdict comes back with a unanimous 5–0 vote in favor of probation for my codefendant and a 5–0 vote in favor of suspension for me. He is a two-sport varsity athlete and I’m an underachieving scumbag whose own adviser failed to support him at the hearing.

There’s no justice in this world—a valuable lesson to learn at a young age, especially if you want to end up on Wall Street. I’ve seen some of the best traders and sales guys get fired at the expense of worthless assholes. Who you know is as important as what you do and how you are perceived is more important than any reality.

Knowing that the dean of students, who is also my English teacher from the previous year, has a soft spot for me, I take the unusual step of appealing the unanimous decision. I make a compelling argument that this is simply an instance of unauthorized collaboration, as opposed to outright cheating. The following day, my suspension is overturned, making me the first and only case in Choate history (that I know of) where a unanimous judicial committee decision has been overturned.

Ode to Liar’s Poker

In Liar’s Poker, Michael Lewis makes reference to the “suitcase goof,” which, as he recollects, started innocuously in 1982 with one trader putting pink lace panties in another trader’s weekend bag, and then gradually escalated until entire contents of suitcases were being replaced with soggy toilet paper.

All of our bosses in fixed income—Paul Young, Phil Bennett, Jim Forese, Mike Corbat, Mark Watson, and Jeremy Amias, and our ultimate boss, Tom Maheras—worked their way up through the Liar’s Poker era of Salomon Brothers from the early 1980s through the Treasury scandal of the early 1990s. Not only do they embody that now-infamous culture, but all the junior bankers go out of their way to embrace and emulate it as well. As analysts, we would sit around over beers after work and share second- and thirdhand stories. “Hey, did you hear what happened at the MDs’ off-site?”

Of course, we had all heard the story. Ed Bowman hired a helicopter and some former SAS soldiers as actors to swoop in and stage a mock kidnapping of Mahir Haddad during the middle of an outdoor team-building exercise. That would have been hilarious had it not been for the fact that Mahir had grown up in war-torn Beirut and had seen close friends and family kidnapped or killed; he was not amused.

Mahir extracted his revenge on the Dino Ferrari that Ed had obnoxiously driven to the off-site, covering it in toothpaste and inadvertently destroying the original paint job in the process. For fear of further escalation, Tom Maheras was brought in to forge a truce and temper the culture of aggressive and mean-spirited trading-floor antics and office pranks.

However, the goofs continued. Just as I was finding my feet on the trading floor, Rick Goldberg, the global head of , set the benchmark with a suitcase prank that quickly became the stuff of Salomon Brothers legend.

On a trading floor, it’s not uncommon for people who are traveling to leave their suitcases right next to their desks. It’s not that they are necessarily afraid of being victimized if they let their bags out of their sight; it’s simply a logistical function of the closets being so far away.

One day, this New Jersey guido-made-good,Vinny Funaro, comes in with a small Samsonite travel bag. He’s off to Montreal for a bachelor party weekend. Goldberg immediately pulls aside one of the analysts and whips out a hundred-dollar bill. “Okay, here’s what I’m going to need you to do. Go down and find the nearest restaurant supply store, or God knows what, and buy me a big, metal, industrial spatula. Can you handle that?” The analyst nods confidently. This was typical Goldberg, getting his foot in the door before dropping the hammer. “Good. Then I’m going to need you to also pick up some dirty magazines. I want raunchy, hard-core porn, as much as you can carry. And it has to be gay.”

“Fuck you,” the analyst shoots back. “I’m not doing that.”

There is no such thing as a hierarchy in times like this.

So Goldberg pulls out two more hundred-dollar bills and says, “How about now?”

The kid nods and grabs the money.

“Okay, but for that kind of money, it better be some raunchy shit. Fisting, bukakke. Don’t hold back.”

The analyst comes back about an hour later. “Sorry, the porn was easy; the spatula took fucking forever.” With that, they wait for Funaro to leave his desk. As soon as he’s off the floor, Goldberg kicks into action with clinical precision. He takes the spatula, bends it into the shape of a gun, and places it at the bottom of Funaro’s suitcase. On top of that, he crafts an intricate nest of pornographic magazines, and then proceeds to construct a sandwich of clothing and gay porn, alternating layers all the way up to the top—where he neatly applies a final layer of clothing, restoring the bag back to its original appearance.

“Say a word and I’ll kill you.” He emphasizes the point, not that he has to; everyone knows where their bread is buttered. And with that, they all watch a short time later as Funaro heads out early to catch his flight and get a head start on his long weekend.

On the following Monday morning, it doesn’t take long for shit to hit the fan. Before he even sits down, Funaro starts losing it. “Which one of you fucksticks did it? Come on, I know Goldberg put you up to it.” He knows no one has the balls to carry out a stunt like that without the order from up top, but he can’t do anything to his boss; all he can do is take it out on the analysts.

Everyone just stares at their screens in silence, trying not to crack up. “Do you fucktards understand what happened to me? My friend from grade school is getting married. A lot of these guys I haven’t seen in years. They aren’t bankers or Wall Street guys. They’re firefighters, cops, and blue-collar guys. You think they understand this shit?”

The gag could not have worked more perfectly. Going through airport security, the gun-shaped spatula set off all kinds of alarms. The TSA agent immediately pulled him aside and asked to inspect the contents of his bag, which of course got no objection on Funaro’s part. The latex-glove-clad agent then started slowly dissecting the sandwich of clothing and hard-core porn, holding each magazine up in the air as if it were radioactive. Meanwhile, the entire bachelor party, having already cleared security, stood there watching this spectacle unfold, asking each other the same questions.

Once security reached the spatula, it became clear that this was someone’s sick idea of a joke. However, it also became clear that this passenger had not “packed the bag himself,” nor was he “familiar with all of its contents,” which triggered an entirely new wave of security protocols. So Funaro and his entire troupe of guidos got held up for another twenty minutes and almost missed their flight. To this day, he has no idea who the culprit was.

When I get to London, it really strikes me how the guys in New York treat us like second-class citizens, as if London is some satellite office. Given the respective sizes of the US and European bond markets, the New York desk generally does more deals in a day than we do in a week. They treat us accordingly, coming through every few months under the guise of “helping” us educate and pitch European clients on targeting US investors. We all know that these trips are an excuse for them to live it up in London, Paris, and Madrid for a week. Of these people, Mike Benton is particularly odious. He’s one of those Americans who immediately adopts the British vernacular with words like “bloody,” “mate,” and “cheers.” He even treats my boss like a tour guide: “Is there a quicker way to Savile Row without taking the bloody tube?”

One day, he comes back to the office and proudly announces to everyone in earshot that he just came back from having a mold of his feet done for custom-made John Lobb shoes. “Bloody expensive at two thousand quid.”

I’m not sure if he thought it would be faster or if he was just too cheap to pay for shipping, but he arranges to have the shoes delivered to our office so that we can interoffice them to him for free in the internal overnight pouch. He asks Chris Nichols, also a managing director, to handle it for him.

“Sure, I’ll have Alan [his analyst] send them across when they arrive.”

“Cheers, mate.”

Like clockwork, the shoes arrive six weeks later, in a shoe box that is neatly wrapped in durable brown wrapping paper. Chris, the custodian of the shoes, is traveling on business when the package arrives, so our shared desk assistant casually leaves the package on his desk.

This just so happens to coincide with a day when I am working late into the night. Other than Kamal Meraj, a friend and fellow analyst, the trading floor is completely deserted. As we’re walking out, I can’t help but notice the package just sitting there. I fill Kamal in on the backstory and relay what a complete douchebag Mike Benton is; we both decide this is too good an opportunity to pass up.

We delicately unwrap the box, taking great care to make sure the tape doesn’t tear the packaging. Inside a smart-looking pouch, we find a work of art. It’s like I’m holding a pair of Fabergé eggs. I should be wearing gloves.

We take the real shoes and carefully place them back inside their pouch and into a shopping bag. I hide the shopping bag in the bottom of one of the desk’s seldom-used communal filing cabinets, where old pitch books, deal folders, and offering prospectuses go to die. We know they’ll be safe there, and it’s a location that can never be traced back to us.

Then I take some bright red, hand-painted, wooden Dutch clogs, which I have just stolen from underneath a desk where the Holland coverage team sits, and stuff them into the John Lobb box. They’re perfect; they even have a colorful cartoonish windmill painted across the vamp and toe cap of each shoe. From there, we surgically wrap the box back up in the original packaging and tape and put it back on the desk.