Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The suburbs – long sneered at for being dreary and stultifying – have always been far livelier and more entertaining than they're given credit for. In this witty and sharply observed account of what it was like to grow up in one in the 1950s and '60s, David Randall gives the other side of suburbia: full of absurdities and happiness, scandals and follies, and inhabitants both sage and silly. Here, at last, is the truth about what life was really like behind the often-closed (but not always net) curtains of our semi-detacheds. This is that rare book: a most unmiserable memoir.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 272

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

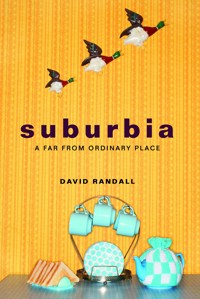

suburbia

suburbia

A FAR FROM ORDINARY PLACE

DAVID RANDALL

First published 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© David Randall, 2019

The right of David Randall to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9296 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

contents

Preface

ONE

The Suburbanophobes

TWO

A Small Scandal in Suburbia

THREE

And Where Do Your People Come From?

FOUR

A Sheltered Existence

FIVE

Suburban Streets

SIX

The Suburban Home

SEVEN

Smoking, Drinking and Suburban Oddballs

EIGHT

Training for Little Suburban Citizens

NINE

Suburban Sundays and the Mystery of Girls

TEN

The Great Suburban Outdoors

ELEVEN

Art and Artlessness in the Suburbs

TWELVE

Suburban Shopping

Appendix: A Suburban Inheritance

preface

This is a book about the suburbs, and what it was like to grow up in one of them in the 1950s and 1960s. It was written for two reasons. First, to capture that experience of a world now largely lost – its absurdities and happinesses, scandals and follies, and inhabitants both sage and silly. Second, to set down some sort of rejoinder to all the disparagement of the suburbs produced by the writing classes down the years, a strain of rather snobbish metropolitan thinking which is detailed in Chapter One. I’ve always found the best way to disarm critics is to concede that they may have a point. When the great American journalist H.L. Mencken received letters disputing, often in far from temperate tones, something published under his name, he would send them his standard reply: ‘Dear XY, You may be right. Yours sincerely, H.L. Mencken.’ The critics of the suburbs may be right, but this book is a small quibble with them, a suggestion that for many of us these areas have been a warming seed-tray in childhood, a reliable base camp for later, tentative, forays into the world, and a place, by and large, of some contentment. My childhood was spent in what now seems a sort of long-lost, semi-detached Shangri-La. Yet all habitats in which you grow up mark you indelibly, and suburbia marked me, not always for the better, I fancy. Here is what happened there.

David RandallSouth Croydon, 2019

ONE

the suburbanophobes

One of the great staples of English fiction over the last century or so has been the character yearning to break free from the oppressively humdrum confines of suburbia. The city, or rather their fantasy of it, seems full of opportunities to throw off the shackles of semi-detached conformity. They imagine that here, amid the bustling anonymity of a metropolis, they will find themselves – liberated at last from the smothering narrowness of Acacia Avenue. And so, exiting towards the bright lights, possibly in some sudden it’s-now-or-never haste, goes our hero or heroine.

One of the very first examples of this genre was set in a thinly disguised Worcester Park, the outer London-cum-Surrey suburb where the events of my book take place. It was written by H.G. Wells, who knew the suburb well, having lived there in the 1890s with Amy Robbins (always known to him as Jane), the woman for whom he left his first wife Isabel, and who became the second Mrs Wells. His house was called Heatherlea, a large villa in The Avenue, the long, broad, tree-lined road that wound its way up the hill from the station to St Mary’s Church. The suburb in his book is called Morningside Park, the name being more or less the only thing about Worcester Park he changes. The principal characters live in a house very similar to his own, in a road also called The Avenue, and the geography of his fictional suburb is exactly as it would have been then in reality. The novel is called Ann Veronica after its heroine, who is just the kind of young woman – intelligent, beautiful, but vulnerable to the approaches of older, more experienced men as she tries to cast off from her moorings – that got Wells’ blood racing. Indeed, in this she bears a resemblance to Amy Robbins, who was his student when they began their affair, and also, in a milder way, to Amber Reeves, his mistress at the time he was writing the book. The latter was twenty-one years his junior and, the same year Ann Veronica was published, she bore his child, a daughter.

In the book, Wells writes that Morningside Park was a suburb ‘that hadn’t quite come off’, invariably taken to be a criticism but more likely a reference to the place being still largely undeveloped forty years after the railway arrived. Ann Veronica Stanley, to give her full name, is a 20-year-old student who lives in a large house with her widowed father, a man of business in London, and his spinster sister. She longs to take up her studies at Imperial College, but her father disapproves of the teaching there and forbids it. She wants to attend a fancy-dress ball in town, but her father forbids it, and this is her breaking point. She bolts, borrows money from a heavy-breathing financier who later tries to force himself on her, joins the suffragettes, gets arrested and imprisoned after a demonstration, and then submits to returning home and becoming engaged to an older, overly upright and besotted Morningside Park neighbour. Her father, still the controlling sort, relents and allows her to attend Imperial College, and there, having broken off her engagement, she falls in love with a married demonstrator, implores him to possess her in terms that shocked several of the book’s reviewers, and runs off with him to Switzerland. Although early in the book she utters three lines of exasperation with Morningside Park (‘Ye Gods! What a place! Stuffy isn’t the word for it!’), what she really wants to break free from is not the suburb, but the restrictions imposed by her father. In terms of what she wants to get away from, the setting is irrelevant: her name might as well be Elizabeth Barratt and her home in Wimpole Street. But then, that seems true of many ‘goodbye dull suburbia’ novels. What’s being fled is not so much a certain kind of bricks and mortar and their ambience as something the main characters, or someone else, has done to bugger up their chance of happiness. It’s the suburbs as scapegoat, quite often.

The fictional character most associated with the suburbs is not one who rejects, but instead positively wallows in them: Charles Pooter, of The Laurels, Brickfield Terrace, Holloway, unintentionally funny star turn of The Diary of a Nobody by George and Weedon Grossmith. Mr Pooter, a clerk in the City, is socially gauche, pompous, and thinks himself a cut or two above tradesmen, shopkeepers, office juniors, and the rather dubious young women his wayward son Lupin brings home. Lupin and the two men Pooter thinks of as his friends, Cummings and Gowing, regularly take the mickey out of him, and a series of accidents and mishaps play incessant havoc with his dignity. His wife Carrie is the sole person to take him at his own value, sharing his hilarity at bad puns and his preoccupation with domestic trivia. He occasionally gets the better of life, but in general it’s a succession of banana skins on which he never fails to slip. Only at the end – in seven chapters added later to bring the work up to book length (it began life as a serial in Punch) – do these pratfalls cease, and Pooter emerges with pay rise, promotion and bonus: professional, if not social, triumph.

The book is funny, but knowing something of the Grossmiths’ background can stifle the guffaws. This, after all, is fun at the expense of a man of limited education, means and horizons being had by two men of decidedly superior social cloth. The Grossmiths – boarding school educated, both successful theatricals, one also an artist and a member of the Garrick, Beefsteak and Savage clubs – were movers in the sorts of metropolitan circles that have ever since tended to chuckle up their sleeves at the poor little untalented, un-chic people in the suburbs. But at least the Grossmiths seem, in the end, to have found a measure of affection for their hero. They were benevolent satirists. Not so with what followed. The gentle fun that the Grossmiths poked was very soon the least of it. It became a sort of badge of belonging for many writers and intellectuals to forcefully condemn the suburbs and those who lived in them.

Barely more than a dozen years after The Diary of a Nobody was published came a book written by Thomas William Hodgson Crosland, a strange individual who combined writing poems full of Christian charity towards the downtrodden with a vicious homophobia that led him to repeatedly try and get Oscar Wilde’s literary executor, Robbie Ross, prosecuted for homosexuality. Crosland’s book, The Suburbans, is so vehement (one imagines his pen digging ever harder into the paper as he wrote it) that it reads almost like a send-up of literary folks’ animus against the people who live in semi-detacheds (or ‘half-houses’ as he called them). Here he is in chapter one, for instance, as he starts to get up a head of antagonistic steam:

To the superior mind, in fact, ‘suburban’ is a sort of label which may be properly applied to pretty well everything on the earth that is ill-conditioned, undesirable, and unholy … The whole of the humdrum, platitudinous things of life, all matters and apparatus which, by reason of their frequency, have become somewhat of a bore to the superior person, are wholly and unmitigatedly suburban.

The poet Hilaire Belloc (great-grandson of Joseph Priestley, president of the Oxford Union, essayist, MP, and resident of a West Sussex windmill) soon joined in with a versifying shudder at the suburbs:

Miserable sheds of painted tin,

Gaunt villas, planted round with stunted trees,

And, God! The dreadful things that dwell within.

Then there was George Orwell (an old Etonian, admittedly not of the ‘Swing, swing, together’ boating song sort) putting into the mouth of George Bowling in Coming Up For Air these angry words:

You know how these streets fester all over the inner-outer suburbs. Always the same. Long, long rows of little semi-detached houses … as much alike as council houses and generally uglier. The stucco front, the creosoted gate, the privet hedge, the green front door. The Laurels, the Myrtles, the Hawthorns, Mon Abri, Mon Repos, Belle Vue … A line of semi-detached torture-chambers where the poor little five-to-ten-pound-a-weekers quake and shiver, every one of them with the boss twisting his tail and his wife riding him like the nightmare and the kids sucking his blood like leeches.

So it went on. Jonathan Miller (St Paul’s School, and Cambridge, actor, doctor, writer, theatre and opera director) invoked the suburbs to express his intense dislike of Margaret Thatcher, and condemn her for her ‘odious suburban gentility and sentimental, saccharine patriotism, catering to the worst elements of commuter idiocy’. And Cyril Connolly (Eton and Oxford, writer, editor of influential literary magazine Horizon, whose grandfather owned Clontarf Castle, County Dublin) put in his two guineas’ worth: ‘Slums may well be breeding grounds of crime, but middle class suburbs are incubators of apathy and delirium.’

In his otherwise marvelous book After the Victorians, the writer and academic A.N. Wilson (prep school, Rugby, New College, Oxford, son of a colonel who became managing director of the Wedgwood pottery firm) wrote this of the suburban homes built in the 1930s, where live the ‘mortgage slaves’ as he calls them:

Each had a scrap of garden behind its privet hedge. Many had a garage. Once inside them, though, and you find that the rooms are poky … miles from anywhere or anything which could be described as interesting. What hopes these miserable little dwellings represent, what spiritual and emotional constriction they must have offered in reality, as hubby went off to the nearest station each morning … and the wife, half liberated and half slave, stayed behind wondering how many of the newly invented domestic appliances they could afford to purchase … No wonder, when war came, that so many of these suburban prisoners felt a sense of release.

Thus, come September 1939, these limited people, doomed never to know the income and lifestyle of the Wilson household, cheerily embraced the liberating possibility of death or maiming rather than face another humdrum day in a semi-detached. Hmmm.

These are not the voices of people having an aesthetic quibble with the use of half-timbered gables on semi-detacheds, faux Jacobean windows on a villa standing in its own shrubberied grounds, or the indiscriminate use of pebble-dash. These are sneers about something way beyond house design. What you suspect to be at work is what we now call virtue signalling: benchmarking themselves as a metropolitan, a sophisticate, a bit of an intellectual player, by showing contempt for those who are none of those things and who’ve made the basic style error of moving into a home built on the outer edge of some city. It reads like snobbery, but I fancy it may also be unconscious resentment coming out on the page – the always dissatisfied thinking classes irked by what they imagine are the lives of contented, unthinking ones.

I first came across such superior attitudes on, of all things, a youth hostelling holiday in Surrey. My brother Mick and I, then about 16, had gone on a little walking tour, and, being us, began with nothing more adventurous than a short train ride to Westhumble, the station that serves Box Hill. We rambled along a South Downs ridge, and, late afternoon, came to Abinger Hammer, the village and its famed watercress beds hugging one of the less arterial sections of the A25. We wandered into a tea-rooms and sat down. At the next table were a middle-aged couple, and, seeing our hiking gear, they asked us if we were by any chance intending to spend the night at nearby Holmbury St Mary youth hostel. We were, and, as ill luck would have it, so were they.

We had ordered tea and bread and butter and were about to start eating it when up piped one of our fellow walkers. ‘I see you’re eating white bread,’ he said. ‘Nasty stuff, white bread. We always have wholemeal.’ Did we realise the difference? they asked. I suppose one of us, probably me, must have been foolish enough to say we didn’t, and so began a lecture on the benefits of brown bread, and the evils of the baking conglomerates that made the white stuff. We chomped away as they spoke, and might, if they’d gone on much longer, have begun to feel a little guilty. But the woman had seen me put two spoonfuls of sugar into my second cup of tea. ‘Ugh! Cancerous white sugar! Didn’t you know?’ I didn’t, and wouldn’t have been bothered anyway, 16-year-olds generally not having reached the age when they worry about developing terminal illnesses. They were, they told us (although by now it must be obvious), Guardian readers. Which paper did I read? ‘The Times, at school,’ I said. ‘But we have the Daily Express at home.’ I might as well have said that our family regularly practised cannibalism. There followed an imploring to try The Guardian, and, for some reason, an extended paean of praise for its music and theatre critic, Phillip Hope-Wallace. (Years later, when I’d got to Fleet Street, I saw Hope-Wallace holding court in El Vino, pausing occasionally to eat a sandwich. I’d love to report it was made of white bread, but not being a wholemeal obsessive, I didn’t notice.)

This appalling couple were still banging on about The Guardian as we trod our way up the lane to the youth hostel. The following morning at breakfast we managed to sit as far away from them as possible (they would no doubt have been disgusted at the cornflakes Mick and I wolfed down). But, as we made to leave, they ran us down, made small talk, and then asked what they’d clearly been itching to enquire. ‘So where exactly do you come from?’ We told them. ‘Ah,’ the man said, ‘the suburbs.’ And they exchanged glances. ‘We’re in town,’ he said, making it sound like Belgravia Square. ‘North of the river. Barnsbury.’ We didn’t give them a chance to elaborate further on their smug gulch. We shook their hands, bade them a lukewarm farewell, and made for the nearest bus stop and home. They damn nearly put me off The Guardian for life.

In my twenties, I would occasionally come across condescension similar to that of the Barnsbury Two, but it was only when I went to work in national newspapers, at the end of that decade, that I found this geographical one-upmanship in full vigour. This was especially the case among columnists and the fancier feature writers, the sort who mistook the invitations they received as part of their job as evidence that they had the makings of a boulevardier. There are, I discovered, few groups so slavishly attached to an aura of fashionability than these. No estate agent has a more acute ear for the social nuances of where one lives. For them, to live outside the reach of the London Underground was to be beyond the pale. Several editors and senior writers I knew used the word ‘suburban’ as a term of all-round condemnation, and, if it came out in conversation where I lived (the outer suburb of Croydon), it was all they could do to keep a straight face. To them, ‘suburb’ and ‘suburban’ were words synonymous with the dreary, conforming, dull and small-minded. To live in a suburb was, to their oversensitive postcode antennae, to be ordinary, unadventurous, cosy, limited, unimaginative and achingly unfashionable. As someone who has lived in the suburbs all but two years of his long life, all I can say in response is that they may be right; although quite why these things should annoy them so much is a bit of a mystery.

Suburb-sneering by the self-consciously smart is unlikely ever to disappear. But some of the atmosphere of antagonism is starting to change, mainly because of what is happening inside the suburbs. They were always more architecturally varied than the critics made out (half an hour’s walk around one would have told them that), and now they are far less socially uniform than they were. In our part of 1950s and 1960s Worcester Park, there were few terraced homes and flats; almost every man had a white-collar job; there was not a black face to be seen; and it was overwhelmingly Anglican, by sentiment or background, if not attendance. Contrast this with where I live now, in South Croydon, which, within a mile or so of my home, has 1920s and Victorian terraces; semi-detached and detached villas ranging in age from Edwardian to 1950s; a parish church, plus ones for Baptists, Methodists and most other variants; an Oddfellows hall; Pentecostal tabernacle; mosque; retirement homes; and several blocks of housing association flats – a complete jumble of habitats, few of which remotely match the clichéd suburbia. And, in the ten homes nearest my own 1920s terraced house, I have four neighbours of ethnic backgrounds different to my own. This is now not unusual. In Harrow and Pinner, for instance, both part of John Betjeman’s Metroland, some 69 per cent and 38 per cent of the residents respectively are of ethnic minority origin. This is another reason why the criticism is becoming muted: it’s one thing to sneer at the Pooters, or take a swipe at the Tomkinson-Smyths up their long, gravelled drive, but quite another to lay into the inhabitants of the diverse, multi-faith, multi-ethnic places the suburbs are becoming. Few of the older suburbans would credit political rectitude with bringing them a benefit, but, in this sense, it has.

TWO

a small scandal in suburbia

In 1953, we (Mum, Dad, and my twin brother Mick and I, aged 2) moved from Ipswich to Worcester Park, a suburb where outer London meets Surrey. Mum and Dad were entitled to think that here, among homes with decent-sized front gardens and plenty of crazy paving, moral standards were high and crime non-existent. This swiftly proved not to be the case. A few days after we moved in, with my father having long since made his bowler-hatted way to the station and thence the office, there came a knock at the door. Mum opened it to find an overcoated man, who raised his trilby, bid her good morning, and announced that he represented the Sunday Pictorial newspaper. Had she, he asked, noticed any comings and goings at a detached house diagonally opposite? She hadn’t. Had she seen cars delivering young women to the house? She hadn’t. And when he tried another tack, she explained that we’d only been here a few days. Off he went, empty-notebooked, and, judging by the number of front gates that bore a little brass plate reading ‘No hawkers or circulars’, he would have learned little from the good housewives of Edenfield Gardens.

Not much more than an hour passed before there came another knock at the door, and she went through the same rigmarole with Reporter Two. She was by now somewhat perturbed. What manner of road was it they had moved into that attracted the attentions of the more lurid Sunday papers? Mum and Dad took the Sunday Express, features on wartime derring-do more its speciality, but she was well aware that there were other Sunday newspapers which took a keen – almost scholarly – interest in wayward Scout leaders, choirmasters with unusual ways of showing an interest in boy sopranos, and other outwardly respectable folk who had faced temptation and succumbed. Mum knew none of the neighbours, and tapping on their door to ask for full details of what had attracted the pressmen was not quite the way she wanted to introduce herself. (People kept themselves in check and at a distance hereabouts. It was, for instance, more than a dozen years before Mum and the lady next door agreed that they would no longer call each other Mrs Randall and Mrs Eyles, but Doris and Beryl. Worcester Park was that kind of place. Less a culture of keeping up with the Joneses, than keeping them at arm’s length.) So it wasn’t until the local paper carried the court case involving the woman who lived diagonally opposite that all was revealed. She had, in a detached house largely hidden from view by a cordon of conifers, been carrying on a lucrative line in abortions – then illegal. With Britain’s most famous amateur abortionist (and murderer), John Reginald Christie, only recently hanged at Pentonville Prison, it was quite a jolt to realise that the same trade, albeit with non-homicidal outcomes (at least for the mother-to-be), was being practised in Edenfield Gardens.

Happily for Mum, the abortionist was not typical of local residents. For many years, all was seemliness, and it was not until halfway through the next decade that a shiver of gossip next ran down the road – and this time Mum was in the know. A married resident had been arrested in a Kingston-upon-Thames public convenience for ‘insulting behaviour’, legalese for seeking or offering a homosexual act (then outlawed), but also the standard charge by which evidence-inventing police fitted up some hapless chap. The reaction in the road was exactly what none of the rougher Sunday newspapers would have anticipated. There was no tut-tutting, pursing of lips, or anything remotely approaching shock. Instead, everyone we knew had a good chuckle. Unkind, but true. After all, what we later learned to call gay were then ‘queers’ or ‘nancy boys’, comical figures who, to us, were either prancing effeminates (as seen on stage and screen), or blokes like our hero who, while living with his wife and children, harboured yearnings which eventually inspired him to hang around the gents in Kingston for the chance of a bit of ‘man love’. Neither legalising their activities, fearing or resenting them, nor, for that matter, celebrating them, crossed our minds in the early 1960s. Homosexuals were too far outside the conventional for that.

A lot of things were beyond the Worcester Park pale. Divorce, for one, and we knew no one who had anything other than a full set of parents in residence, and no friend ever reported their home echoing to the sound of flying crockery or other serious domestic unpleasantness. Anyone seeking to understand the social atmosphere of the 1950s and ’60s could do worse than consult divorce statistics for that and subsequent periods. In 1958, there were, for a population above 50 million, only 22,654 divorces. By 1969, this had risen to 51,000, and then, in 1969, came the Divorce Reform Act, which allowed couples to divorce without proving adultery or cruelty. That, and a big reduction in the stigma attached to a broken marriage, meant that, just three years after the Act, in 1972, divorces totalled 119,000 – quadrupling in just eleven years. By 1993, there were 165,018 divorces, more than seven times the number in the late 1950s.

There must have been passions behind the painted front doors of these streets, but we knew no one who had them, let alone showed them; no one who had what we now call ‘issues’; no one who raised Cain, nor even their voice. And we certainly didn’t know anyone who had a sex life. This rather goes against the grain of the Great Suburban Cliché, part of which promoted the belief that illicit couplings were discreetly widespread down any street where flowering cherry trees grew. Milkmen and other tradesmen, went the legend, would be lured into homes by wives in quilted housecoats, and emerge half an hour later, red-faced and with another sure-fire address to tell their mates about. Au pairs from Europe would be ever-ready to induct husbands and older sons into their uninhibited Continental ways. And behind curtained picture windows, house keys would be tossed into empty salad bowls, lots drawn, and wives swapped – a feast of sex on Wilton carpets and velour settees as cost accountants and beauty product demonstrators, project managers and dental technicians cast off the oppressive conformity of their suburb and gave in to desires that had been bottled up for too long. The reality, of course, was that part-time orgiasts were very few in number. For the housewife at a loose end, coffee mornings and outings with the Townswomen’s Guild were more Worcester Park’s style.

Nothing more typified the daily absence of drama than the daily drama on the radio, Mrs Dale’s Diary, whose defining feature was that very little happened. The humdrum doings of this doctor’s wife and her family in the Middlesex hinterland were thus truer to life than today’s soap operas, in which sensations abound, and no contentment goes unpunished. Mrs Dale’s scriptwriters preferred life unruffled, the only hint of tension being what might lie behind her oft-used opening line about her GP husband – ‘I’m rather worried about Jim’ – the cause of the concern invariably turning out to be a spot of dyspepsia, or wilt on his begonias, and not, as it would be today, morphine addiction or the discovery he had a transgender lover. About 7 million listeners tuned in every day to follow what, in fact, needed very little following, and it was only later in the 1960s, when the BBC decided to pep things up a bit with fatal accidents and some mild hanky-panky among the Dales’ relatives, that the audience began to drift away. By then, Ellis Powell, the actress who played the title role for the first fifteen years, had gone. Sacked on account of her alleged over-fondness for a sherry or three, she worked briefly as a demonstrator at the Ideal Home Exhibition and cleaner at a hotel before dying three months later at the age of 57. The BBC dealt with this, as they did with all unpleasantness, in true suburban style by the simple expedient of never referring to it.

Worcester Park was a district which began, as so many suburbs did, with the pushing onwards and outwards of a railway. The London and South Western Railway (terminus at Waterloo, major junction at Wimbledon) decided to extend their line to reach Epsom, and, in 1859, where the pioneer tracks ran on a bridge over the road between Cheam and Malden, they put a station, even though there was nothing much there save for a couple of farms. Originally called Old Malden (because that was the nearest named place), it was later re-christened Worcester Park, since, in the days of Nonsuch Palace (three miles to the south-west, and pulled down in the seventeenth century), the Earl of Worcester had been steward of the hunting park whose deer and chases had long since been replaced by cattle and farm tracks.

The first houses unconnected with farming were a terrace of workman’s cottages built a quarter of a mile south of the station in what was later called Longfellow Road (Prime Minister John Major grew up in a bungalow a little further down this road). Some shops and villas went up alongside the Cheam–Malden road, and a post office, hotel and other necessaries were built around three sides of a curious little square the other side of the main road from the station. On a new roadway due west of the station, and leading up a gentle rise to where St Mary’s Church was later built, large detached villas with coach-houses appeared. And that, a little modest extension apart, was Worcester Park until, in the 1920s, electrification of the train line led to farms selling great swathes of land for housing. Over the next fifteen years, homes and a main road of shops went up, and the Worcester Park we knew was created. But as with most suburbs, you needed to be a resident to tell where ours began and ended, for it merged (or, rather, seeped) into North Cheam and Stoneleigh to the south, Ewell to the west, and New Malden to the north and east. Our home was on the western side, in Edenfield Gardens, about a third of the way along this scale geographically, and half the way architecturally, and so socially. People here were remarkably similar in outlook. Our road might well have been the reservation created by the authorities for a particularly small and homogenous tribe.

THREE

and where do your people come from?

Throughout my childhood, the people I knew were drawn almost exclusively from our side of Worcester Park. I knew no one higher on the social scale than the inhabitants of our area’s detached homes, and no one from anything all that much meaner than our semi. There was, briefly, when I first went to grammar school, a friendship with a boy who lived the other side of Central Road in – or, to Mum, dangerously near – some council housing. He dropped his aitches (and, correspondingly, pronounced the letter h as ‘haitch’), both worrisome traits to my mother who, for a time, threatened me with elocution lessons if I picked up any more bad speech habits. But, this lad apart (and the friendship soon withered and died, as they do when you’re 12 or 13), I never knew anyone from a different background or who spoke differently.