13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

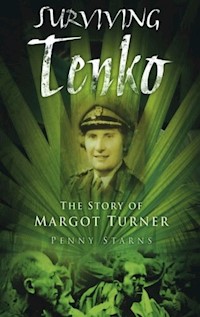

The dramatic tale of Margot Turner's survival as a prisoner of war during the Pacific conflict of the Second World War inspired the 1980s television series Tenko. The cargo ship on which she was evacuated from Singapore in 1942 was shelled, leaving her on a makeshift raft with sixteen other survivors. One by one they perished, leaving her along, burnt black by the sun, and suffering from heat exhaustion and dehydration. Discovered by a Japanese destroyer, she was imprisoned on Banka Island and nursed back to health by nuns. A nurse by profession, Margot was initially permitted to help run the operating theatre on her recovery, when, unexpectedly she was arrested by the dreaded Kempeitai and thrown into Palembang jail. There, crammed with murderers and rapists in a filthy cell, she spent six months living in daily fear of joining the many prisoners who were noisily tortured and executed, before being returned to the prisoner-of-war camps for the duration of the war. In this, the first biography for forty years, Penny Starns describes the often horrific but occasionally heart-warming experiences of this unbreakable woman who, not content with surviving the war, went on to become a brigadier and matron-in-chief of the British Army nursing services. Using recently released material from the National Archives and Turner's own words, Starns re-analyses the Pacific conflict against a backdrop of one person's incredible fortitude and strength, and brings the story of a remarkable woman to life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated with love to my father, Edward A. Starns

Contents

Title page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. The Young Margot

2. Nursing in India

3. Japanese Expansion

4. The Fall of Singapore

5. Palembang

6. Chinese Cabbage and Kang Kong

7. A Higher Authority

8. Confronting Diseases

9. The Kempeitai

10. Congsi System

11. Riddles and Rumours

12. Regaining Confidence

13. Ascending the Ranks

14. This is Your Life

Appendix: Second World War Timeline

Index

Copyright

Acknowledgements

The process of writing this book has been greatly assisted by military personnel who generously helped me during the research for my PhD thesis into nursing history. They gave me their time along with valuable insights into the field and history of military nursing; they include Colonel Gruber Von Arni, RRC, Major Jane Titley (retired 1995), Major McCombe and the late Dr Monica Baly. In addition, I am grateful to a number of archivists, particularly Elizabeth Boardman, Jonathan Evans and Susan McGann, who assisted this extensive research process.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank my friends Joanna Denman, Derrick Shaw, Charlotte and David Hodes, the late Brenda Wood, Jo Foster and Cathy Nile for listening to my ideas as always, and for their practical support. I extend a heartfelt thank you to my father who first encouraged my love of history and has patiently supported my quest for knowledge. I am also indebted to my editor Sophie Bradshaw and Abbie Wood at The History Press for their patience and guidance. Special thanks are due to my three sons Lewis, Michael and James for keeping me on track while I wrote this biography and to my brother Christopher for his encouragement. In addition, I am grateful to all those military nurses past and present who have helpfully recounted their experiences in the field of combat in order to provide the context for Dame Margot’s story. Please note that all memorabilia relating to Dame Margot, including the powder compact with which she collected her precious rainwater whilst adrift on her raft, is held at the Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Nursing Corps Museum, the Royal Pavilion, Aldershot.

Sources

The main primary source material for this biography has been supplied by the Imperial War Museum in the form of Dame Margot Turner’s oral history interviews. Additional primary source material was obtained from The National Archives, mainly War Office Records, Medical History Records, Ministry of Health Records and General Nursing Council Records. Some contemporary newspaper articles have also been consulted. Secondary material includes an earlier biography of Dame Margot that was written by Sir John Smyth, entitled The Will to Live, and published in 1970; and an account of the experiences of women interned in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps written by Lavinia Warner and John Sandilands, entitled Women Behind the Wire, which was published in 1982.

All the royalties resulting from this book will be donated to the charityHelp for Heroes.

Introduction

Much of the literature concerning women and the Second World War has focused on the European conflict. With this emphasis on European battles and victories there has often been a tendency to overlook the brave and resilient women who were captured and interned in the Far East. Yet these women were truly remarkable in their own imitable ways. They established all-female societies within the confines of Japanese prisoner-of-war camps and ran these societies along the lines of liberal democracies, despite the tyranny of their overseers and the deprivations of their captivity. This book charts the life of one of these courageous women, an outstanding military nurse named Dame Margot Turner. Before summarising her experiences, however, it is perhaps pertinent to briefly outline the history of military nursing and its role as a vocational profession with noble and honourable roots.

For much of the nineteenth century British nursing lacked a clear professional identity. The sick were cared for more often by relatives and friends than by individuals in possession of recognisable nursing skills. Additional care was provided when necessary by religious sisterhoods and domestic handywomen. Military nursing was predominantly a male domain as women were considered to be too delicate to care for severely injured men. During the Crimean War the War Office did permit a party of female nurses, led by Florence Nightingale, to nurse the troops in Scutari. This move was viewed as an experiment and, despite the myths that have surrounded the Nightingale legend, the War Office did not fully endorse a commitment to female nursing until after the Boer War. Nightingale had, however, provided the initial breakthrough necessary for the formation and expansion of a female military nursing service. She had also established a more humane and hygienic system of care for wounded soldiers. Upon her arrival in Scutari the hospital was overflowing with sick and wounded men. Some of the men had previously been onboard ships for over three weeks with little in the way of care and minimal rations. Once they became hospital patients many were left to lie aimlessly in soiled uniforms and bandages:

Hell yawned. Want, neglect, confusion, misery … filled endless corridors … The very building itself was radically defective. Huge sewers underlay it, and cesspools loaded with filth wafted their poison into the upper rooms; here there was no ventilation. The stench was indescribable. There were no basins, no towels, no soap, no brooms, no mops, no trays, no plates, stretchers, splints, bandages – all were lacking.1

Nightingale quickly organised her nurses into an efficient team and laboriously scrubbed and cleaned every inch of the Scutari Hospital. Undoubtedly she was the beloved, gentle lady with the lamp to her wounded soldiers, but she was simultaneously a formidable tour de force on their behalf. Reams of letters poured out from the hospital directed to the British War Office, penned by Nightingale herself, which detailed the desperate medical situation and the scandalous shortages of basic hospital supplies. More importantly, Nightingale knew exactly how to get her own way, and threatened to inform the press if supplies for her soldiers were not forthcoming. In addition to setting up a clean and hospitable environment for the wounded men, she established a reading room for their convalescence and a method by which they could send a portion of their wages back home to their wives and families. Not content with merely reorganising the hospital and improving the lives of the sick and wounded, Nightingale also compiled medical statistics, and later assisted Henri Dunnant with the founding and organisation of his international Red Cross movement.

Following the Crimean War a grateful British public donated sums of money and established the Nightingale Fund. Money from this fund was used to create the first secular nurse training schools to be based on Nightingale’s principles. Thus, in 1860 a military nurse training school was founded at Netley and a civilian nurse training school at St Thomas’ Hospital. In order to comply with Victorian conventions Nightingale established dormitory style homes for probationer and trained nurses and insisted that their characters were rigorously evaluated before they entered training schools. It was important for all nurses to avoid any whiff of scandal and to conduct themselves in a ladylike manner.

Military values were incorporated into both military and civilian training schools and these revolved around a sense of duty, self-sacrifice, discipline and respect for authority. Nightingale likened the effects of military nursing to that of a pebble thrown into water; the ripple effect of kindness, nurturing and servitude to the wounded soldier assisted his recovery and instilled him with memories of a dignified nursing service. The process also reminded the soldiers of their wives, girlfriends, sisters and mothers back home, and boosted their morale as they recalled their homes and hearth. She often compared the military nurse with the soldier in terms of the discipline that was required by both. Discipline, she argued, was what made people ‘endure to the end’. Training in obedience was essential to make sure that ‘every person did their own duty rather than every man going their own way’.2

By the turn of the century the Nightingale nurse training system had been adopted across the country, and as Britain prepared for the First World War military nursing became a vital component in the drive towards nurse registration and the female suffrage movement. As Dr Summers has argued: ‘It was thought that women’s necessary services in war demonstrated their de facto equality with men and their right to franchise.’3

The Representation of the People’s Act in 1918 gave limited voting rights to women and by 1919 nurses had won their thirty-year battle for nurse registration and government recognition. However, the Nightingale system had ossified in the civilian field, and left little room for improvements in working conditions and nursing practice. Military nursing, in contrast, had adapted to modernity, and maintained its emphasis on leadership and war preparation in terms of medical and health care delivery. Military nursing was considered to be the elite field of nursing, a profession founded on strong principles and military value systems. Therefore, while many civilian hospitals struggled to recruit young girls for nurse training, once their training and registration was completed, the military nursing field had no problem whatsoever in attracting these girls into their ranks. As one of the later military nurse recruitment pamphlets pointed out:

You will work in up to date hospitals with modern equipment nursing service women as well as soldiers, their wives and children, and civilians. Your career in the QAs will normally bring a fresh posting every two years, perhaps to Hong Kong, Nepal, West Germany, Cyprus, Northern Ireland … wherever you go, you may have the opportunity to use any specialist qualifications you may possess, and plenty of time to be a good nurse. And except in the rare emergency you will never find yourself with too many patients. Off duty: Comfortable accommodation is provided for everybody … you are well looked after in the modern army. You can join in with other serving men and women in dramatic and folk singing clubs. Your social life – in effect – can be as active and varied as you like.4

The prospect of nursing with the elite, rendering a patriotic and vital service to their country, travelling across the world and being relieved of the normal domestic expectations of womanhood, were all cited by girls as reasons for entering the military nursing service. Throughout the Crimean War, Boer War and the First World War, British military nurses became renowned for their commitment to their country, their sense of dignity and duty, and their self-sacrifice. In addition to their founder Florence Nightingale, the nursing profession became littered with the names of extremely brave women such as Edith Cavell. Viewed in this historical context, therefore, the extraordinary life of Dame Margot Turner clearly followed a finely carved path of heroic nursing tradition.

Among the memoirs of women who served during the Second World War, those of Dame Margot Turner stand out like a beacon of light. Indeed, her experiences were so unusual and dramatic that they prompted the highly successful 1970s television series Tenko. Dame Margot was working as a theatre sister with the QAIMNS (Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service) in Singapore at the time of its surprise capitulation in February 1942. British and Indian troops were quickly evacuated. Along with about 350 others, Dame Margot boarded a cargo ship in Keppel harbour in an attempt to escape the invading Japanese forces. This ship was subsequently shelled and its mixed cargo of military personnel and civilians were tossed unceremoniously into the sea. After swimming to a nearby island, a few days later Dame Margot boarded another cargo ship bound for Batavia; this was torpedoed and once again she found herself fighting for her life.

Surrounded by shark-infested waters and struggling to keep on top of the strong, dangerous currents, Margot and another QA managed to construct a makeshift raft. One by one, however, the others on the raft, including a small baby, died. They perished as a result of their wounds, heat exposure and dehydration. Burnt black, and blistered by the fierce Asian sun, Dame Margot survived on her raft by eating seaweed and drinking rainwater that she had collected in her powder compact. Eventually she was discovered by a Japanese destroyer and its crew mistakenly believed her to be Malayan because of her black skin. When the true nature of her nationality was revealed she was initially interned on the small island of Banka, near Sumatra.

For the next three and a half years Dame Margot lived and worked in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, even enduring a spell in the notorious Palembang prison with murderers and thieves. Her experiences were often horrific, but occasionally heart-warming and surprising. The following pages tell the dramatic story of how she survived her shipwreck ordeals and internment at the hands of the Japanese to become a brigadier and the matron-in-chief and director of the Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Nursing Corps.

Notes

1. L. Strachey, Florence Nightingale (1997), pp. 16–7.

2. M. Baly, As Miss Nightingale Said (1991), p. 91.

3. A. Summers, Angels and Citizens (1988), p. 182.

4. Ministry of Defence Recruitment Pamphlet (HMSO), 1981.

1

The Young Margot

It was somewhat ironic, given her later association with the Japanese, that Margot Evelyn Marguerite Turner was born on 10 May 1910 in Finchley a mere four days before the grand opening of a major Japanese exhibition in the White City area of London. Designed to underpin the renewal of an Anglo-Japanese alliance, the exhibition occupied 242,700 square feet and included nearly 300 exhibitors. Furthermore, it was an unprecedented and ostentatious display of Japanese culture that generally portrayed Japan as a progressive and modernising nation with a complementary empire. To the chagrin of the Japanese government, a few exhibitors chose to highlight the poverty and plight of the peasant population and showed examples of officially sanctioned barbaric behaviour; but overall, visitors were impressed by images of Japanese gardens, exquisite silk kimonos and Far Eastern prosperity. The exhibition ran until 29 October 1910 and received favourable and polite reviews in the British press. Although some more patriotic journalists smugly pointed out that while Japan’s Empire of the Sun was indeed enviable, the sun never went down on the British Empire.

The year of Margot’s birth was eventful for reasons other than the major Japanese exhibition. It was the year that marked the death of King Edward VII, Florence Nightingale and Leo Tolstoy. It was also the year that Sir George White began his highly successful aircraft manufacturing business in Filton, Bristol. There was a violent upsurge in the women’s suffrage movement and the Liberals swept to victory in the December general election. Increasing international tension had prompted health and welfare initiatives to improve potential recruits to the armed forces and Britain was involved in an expensive naval arms race with the kaiser’s Germany. This volatile situation had created a distinctly jingoistic and militaristic Britain, which hurtled unstintingly towards the First World War.

In Margot’s local area of Finchley, political and world events were temporarily usurped in 1910 by the grand opening of the East Finchley Picturedrome. Now a grade two listed building it was also known as the Phoenix cinema, and was one of the first to introduce sound pictures in 1929. Margot’s family were of quiet middle-class origin, and her mother Molly Cecilia and father Thomas Frederick Turner, a solicitor’s clerk, were already the proud parents of two sons, Dudley and Trevor, before Margot appeared on the scene. A younger brother named Peter arrived soon afterwards, and it was not surprising, given all this brotherly influence, that Margot became renowned as a ‘tomboy’ type during her youth.

Physically, Margot was as strong as an ox and revelled in sports of all kinds. In her adolescence she particularly excelled in swimming, hockey and tennis. By this time she was well-built, tall and with a handsome rather than a pretty face. Friends of the family constantly remarked on her twinkling pale-blue eyes, good bone structure and dishevelled light-brown wavy hair. They described her face as one that expressed a certain degree of kindness combined with a mischievous, wry sense of humour. Taller than most of her peers by the time she was 15, Margot was an imposing figure with an understated natural air of authority.

Britain during the interwar years was dogged by industrial strife and economic depression. Six national hunger marches began in 1922 and long-term unemployment was an increasingly worrying problem for over a million families. The National Strike in 1926 was a turning point in labour relations and the Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin took a firm stance against the miners and their supporters by bringing in the troops to settle the matter. There continued to be fluctuations in unemployment figures, however, and the north/south divide was apparent, with the latter being more affluent and able to ride the economic downturns.

The economy did not fare much better in the 1930s but at least some improvement was in sight. Nevertheless, just as the economy seemed to be on the mend, the country was rocked by another problem that shocked the nation. On 20 January 1936 King George died and his son became King Edward VIII; a few months later it was obvious that the latter had embarked on an affair with double divorcee Wallis Simpson. A determined Stanley Baldwin dealt with the subsequent abdication crisis in a forthright and relatively swift manner. Thus, by 8 December 1936, the king had made up his mind to give up the throne for the woman he loved. His brother, therefore, became King George VI. But the country was divided for a long time afterwards, with over 60 per cent of the British population expressing some sympathy towards the abdication dilemma faced by King Edward VIII. This did not mean that they were averse to the new King George VI. Indeed, the quiet, dignified manner of the latter endeared him to a good many people, and his wife Queen Elizabeth proved to be an astonishing and much-loved asset to the throne.

The interwar political events in Britain were turbulent and unpredictable. Many of them were overlooked by the young Margot, however, who was more interested in sport and animals than politics at this stage. Whenever she was asked about her early years Margot always maintained that her childhood was very happy and totally uneventful. But there was no doubt that she had succeeded in suppressing a number of distressing emotions. Her father died when she was only 13 and she had wrestled with this grief in a very private way. Margot did not believe in airing her feelings to all and sundry, and stoically mourned her father in a peculiarly insular way. She studiously read the Bible, hoping to gain some divine perspective on the issues of life and death, and immersed herself in long periods of quiet introspection and prayer. She also spent time comforting her mother and brothers and discussed her deep religious faith with them at length. Margot was a very popular girl and her classmates at Finchley County School described her as forthright, honest, loyal, compassionate and dedicated. She was also practical, thoughtful and self-disciplined. Eventually her mother acquired a second husband, a gentleman named Ralph Saw, who Margot readily accepted as her stepfather and later described as a perfectly charming man.

It was around this time that the family moved to Hampstead and the teenage Margot began to think about her future career path. Being an outdoor, adventurous girl, Margot could not bring herself to contemplate a career that might confine her to an office. Moreover, it seems that a number of influences and experiences guided her, almost by stealth, into the nursing profession. The large volume of men who had returned from the First World War physically dismembered and mentally crippled had ignited her sympathy and compassion. From the age of 8, like everyone else in Britain, she was surrounded by people who had been affected either directly or indirectly by the tragic conflict. The influenza pandemic of 1918 had also left an indelible impression on the young Margot.

Since, in the days before vaccines and antibiotics, many victims only survived because of the timely intervention of good nursing care, it became clear to the practical Margot that nursing was not only a useful profession but one that could make a real difference in terms of serving humanity. Furthermore, the profession appealed to her religious sensitivities. Some of her older school friends had already embarked on a nursing career and a chance meeting with these girls in 1930 clarified her thoughts. Consequently, Margot began her nurse training at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London the following year.

St Bartholomew’s was affectionately known as Bart’s by all its doctors and nurses. The hospital was originally established in 1123 by a favoured royal courtier named Raherus. While on a pilgrimage to Rome, Raherus fell seriously ill. In a feverish state he had prayed for recovery, vowing to God that he would build a hospital for the ‘recreacion of poure men’ should his wish be granted. He was rewarded with a vision of St Bartholomew and the saint instructed him to build a hospital with a priory attached. Raherus duly obliged and St Bartholomew’s became one of London’s finest hospitals. By the time Margot began her nurse training in 1931 Bart’s had an enviable reputation and belonged to a group of highly esteemed London hospitals that operated within the voluntary hospital sector.1

With its traditional reputation for excellence, Bart’s could afford to operate elitist recruitment practices and all job interviews were painstakingly gruelling. Each year nearly 50 per cent of girls who were interviewed for a nurse training place were rejected out of hand. The others needed to be approved by the discerning matron Miss Helen Day and, as probationers, would begin a six-week course at the preliminary training school in Goswell Road.

The probationer drop-out rate at the end of the six-week period was often much more than 50 per cent, though in Margot’s cohort twenty probationers began the training and ten of these had left before the end of the preliminary course. After this training period, the remaining probationers began working on the wards at Bart’s for a trial period of three months. A final selection process was then conducted by Matron and the hospital governor in an imposing interview room with two adjacent doors. Selected probationers left the room by one door and rejected probationers by the other. Given the high rejection rate Margot was greatly relieved when she passed this final selection interview. Once accepted onto the four-year training course, she moved into the lively nurses’ home, which housed around 520 nurses, and settled into her new career with enthusiasm.

Nurse training at this point in time was not for the faint-hearted. The hours of work were extremely long and it was not unusual for a probationer to work at least seventy-two hours a week, sometimes only having one day off a month. In addition to the daily grind of ward work, probationers also needed to study in their off-duty hours in order to pass their examinations. Rates of pay were poor, but the young girls were at least provided with safe accommodation and meals. They had very little time for a private or social life and were rigidly supervised by a home sister and Matron. Furthermore, any probationer who met a man and chose to marry was forced to instantly resign from the profession, since nursing was considered to be a vocation that required total dedication.2

A typical day for Margot began at 6 a.m. with a wash and breakfast. Ready for duty and on the ward by 6.30 a.m., she would then check all the patients’ temperatures, blood pressures and pulses before administering their tea and breakfasts. Bed-making, washes and bed baths, operating theatre preparations and dressing wounds kept the probationers occupied for most of the morning. Senior probationers would accompany trained nurses on their medicine rounds in order to learn the correct dosage and administration methods of individual drugs. The more junior probationers were expected to clean the bedpans, vomit and sputum bowls, and the shelves and walls of the sluice. During the patients’ visiting hours they would clean cupboards, roll bandages and wash and prepare the stainless steel instruments for sterilisation. Hot kaolin poultices were prepared each day to draw out the infection from abscesses and septic skin areas, and frothy mixtures of egg white were whisked and placed on bed sores and exposed ulcers to aid healing. Despite their early morning start, probationers did not complete their day shift until 8 p.m. There was just enough time for them to eat supper, drink cocoa and retire to bed.

Life in the nurses’ home was governed by a specially designated home sister and a list of strict rules about behaviour. Notices were posted on just about every wall, with instructions on how to keep the kitchen and utensils clean and the bathroom spotless. Probationers were instructed to ration their hot bath water, on the grounds that others would also need to use the supply and the fact that having a bath which was too hot lowered the vitality of the nurse and reduced their resistance to infection. There were also amusing notices designed to reduce electricity consumption, like the instruction to young probationers to eat bread rather than make toast, because bread was better for them and more nourishing than toast!

Each individual room in the nurses’ home contained very basic furniture: an iron bedstead and lumpy mattress, an old battered-looking wardrobe, a freestanding black, iron-framed mirror and a bedside table. A long list of rules was posted on the inside of every door and nurses were usually informed that they needed to turn their mattress over before making their bed and attending breakfast, and to open the windows whatever the weather in order to air their rooms. All suitcases were usually labelled and kept in a separate room to prevent some of the more homesick probationer nurses from running away in the middle of the night.

The need to conform to a seemingly endless set of rules and regulations deterred most girls from entering the nursing profession, but these strict practical codes were accompanied by another set of rules which governed behavioural and personality traits. According to these, probationers needed to conform to specific and rather angelic characteristics. Official guidelines produced by nursing magazines stated that a nurse probationer needed to be intelligent, possess cleanly habits, a perfect temperament, good physical stamina, natural obedience, an ability to accept discipline, mental and emotional stability, and smart appearance. Indoor and outdoor uniforms were provided by the hospital, and when off duty nurses were expected to wear clothes that stressed modesty and prevented any possibility of provoking excitement in the opposite sex. A nurse also had a duty to take care of herself, as one article explained:

Passing her life amid scenes of sorrow, suffering and the results of what she has been taught to consider sin, she tends to become morbid, introspective and cramped. She must, therefore, off duty, seize every chance of relaxation in any sphere unconnected with her work.3

Matrons and nursing home sisters were trained to watch out for signs of melancholia and other character defects in their probationers, but despite their concerted and occasionally misguided efforts, a large number of probationers did not continue their nurse training past the first year. Homesickness was a huge problem for a lot of young girls, and the unfamiliar hospital territory was daunting for many. Monica Dickens recalled her early days as a young probationer as follows:

For the first few days I groped my way through a dust storm of new impressions, baffling orders and mystic phraseology, but gradually the dust began to settle into the pattern of hospital life. What had seemed like chaos at first emerged as a routine so rigid that it superseded any eventuality. The ward work must go on. That locker must be polished without and scoured within, though death and tragedy lie in beds on either side. Soon I could hardly imagine a time when I had not done exactly the same things at the same time each day. I sometimes caught myself thinking how deadly the work would be if it were not for the patients, forgetting that without patients there would be no work, for it seemed to have an independent existence, which nothing could ever stop.

If all the beds were empty one would still come on at seven o’clock and push them backwards and forwards and kick the wheels straight.

As it was, life became more bearable with each day’s knowledge of the patients and the realisation that they were people, not just bodies under counterpanes whose corners had to be geometrical. Of course, there was hardly any time to talk to them, but sometimes, closeted behind screens to give a blanket bath, you could get down to a good gossip, until a long white hand drew back the screen to admit the ivory face with its fluted nostrils and fastidious lips. ‘Neu-rse’ – Sister Lewis’s voice had a kind of disdainful creak – ‘you’re giving a blanket bath, not paying a social call.’ She was on speaking terms with me by now, or at least on telling-off terms. I was responsible for an unmentionable little apartment called the sluice, which she would enter every morning at nine o’clock, almost changing into old shoes to do so. She would sniff delicately and touch things with her fingertips, but her eye was ruthless. There was usually something that had to be cleaned again and I would have to miss part of the half hour’s break we were allowed for making our beds, changing our apron and having a cup of coffee.

If I had been surprised by the capacity of the nurses’ stomachs at breakfast, I was staggered when I did get time to go to the dining room for what was known as lunch. The ends of yesterday’s long loaves were on the table, with a mound of margarine and a bowl of dripping. I tasted the dripping once, and tasted it all day in consequence. The next meal was called dinner. This was served at midday, except for the senior nurses, and there were all the white pigeons again, ready to make up for only two slices of meat by quantities of potatoes and as many goes of rice pudding they could manage before sister said Grace. Tea was at four and the bread was new and doughy, and had to be cut into hunks anyway, and supper was at half past eight, when one came off duty. It was usually sausages and disguised pies, and perhaps blancmange and cold rice pudding left over from dinner. One thing that hospital taught me was to eat all sorts of puddings I had been refusing since nursery. Hunger compelled it. My appetite grew enormous and I saw myself becoming one of the doorstop and dripping brigade, with my apron growing tighter each day and my dress straining at the seams.4

All probationer nurses put on weight during the first few months of their training due to the heavily loaded, carbohydrate-filled diet. Food and lodging were deducted from the probationer’s pay packet at source and many hospitals cut food costs by feeding their nurses as cheaply as they could manage. Nursing was, and still is, a profession that required a lot of stamina and energy, and therefore it was considered appropriate to stave off the hunger pangs of young girls by filling them full of stodgy food. For some girls the combination of strict discipline, unfamiliar surroundings and poor-quality food increased their sense of homesickness, and the drop-out rate for young probationers was always highest during the first year of training.

Margot took to nursing like a duck to water. She had a practical common-sense approach to life and her physical stamina stood her in good stead. It was not long before she made some firm friends and developed a close camaraderie with fellow probationers Nancy Mitton and Jenny Kemsley. They supported each other wholeheartedly through the ups and downs of training school, and spent their off-duty hours and vacations gleefully sharing humorous stories, jokes and experiences. All three girls were mischievous, vibrant and adventurous.

The rigid conformity of hospital routines were like straitjackets on young would-be nurses and in off-duty periods, as nursing magazines advocated, they let their hair down as much as possible. Relaxation was always regulated to some extent by Matron, however, and certain pastimes were frowned upon. London probationers had an added bonus, in that the capital’s theatres were in the habit of sending batches of complimentary tickets to nurses as a thank you gift for all their hard work. Margot, Nancy and Jenny took full advantage of these theatre gifts, and also managed to fit in the time to go riding, swimming and dancing. Margot was a big fan of Fats Waller and loved dancing to all forms of jazz music. The years she spent in nurse training may have been exhausting and demanding but they were also filled with fun, friendship and a sense of achievement.

In 1935 Margot successfully sat her final hospital exams and became a State Registered Nurse. She stayed at Bart’s for a further six months to undergo theatre nurse training and was about to sign up for another six months when a chance meeting changed the course of her life. Nancy’s sister Eleanor returned to Britain on leave from the Queen Alexandra’s Royal Imperial Nursing Service (QAs), and during a weekend visit to Nancy’s home Margot was introduced to Eleanor, who regaled her with stories of foreign travel and adventure. Margot listened avidly to these accounts of military nursing in different countries, cultures and lifestyles with a growing sense of fascination. She had always wanted to travel and explore the world and she quickly recognised that the QAs offered an ample opportunity for her to fulfil her ambition.

Rejecting a further contract with Bart’s in favour of foreign adventure, Margot firmly set her sights on becoming an army nurse. She later claimed that she was also attracted by the QA uniform, which included bright red capes. Officially called tippets, the red capes were originally designed to hide the female sexuality from the ordinary ‘Tommy’ because army officers believed that a nurse’s modesty needed protection from sexually deprived soldiers. With Margot’s natural air of authority, however, it is unlikely that she needed such protection.

Margot began her six-month military probationary period at Cambridge Military Hospital, Aldershot, and was later gazetted and given a bronze medal to wear on her cape. This medal indicated her military staff nurse status. By Christmas 1937 she was working as a general nurse in Millbank Hospital and enjoying life in London once again. For a time she was allowed to ride the Life Guards’ horses that were stabled at a riding school near Knightsbridge, and she also attended countless military ceremonies. But although Margot enjoyed being back in London she was impatient for an overseas posting. After all, she could hardly describe her QA journey, which thus far had taken her from London to Aldershot and back again, as being particularly adventurous. Since she was not allowed to request a posting, she simply had to wait her turn. Nearly a year later, in September 1938, the eagerly anticipated posting orders arrived. Margot was destined for Karachi, India, aboard a ship named Neuralia, a journey that would take three weeks to complete. This news delighted her immensely, and on 5 November she set sail with enthusiasm and joyful anticipation.

On the tortuous and lengthy route to Karachi, Margot was able to spend some time in Gibraltar, Malta and Aden while the ship refuelled and picked up more passengers. She finally disembarked with a sense of wonderment at her destination on 26 November. Entranced by the colours, smells and market place hum of Karachi, Margot was very reluctant to travel onwards to the small military station in Bareilly. This last leg of her journey encompassed the Sind Desert and Lahore. The train was uncomfortable and she was besieged by flies, intense heat and dust. Upon arrival, however, her initial impressions were favourable. Bareilly had a temperate climate in November, with beaming sunshine during the day and moderately chilly evenings. The area was covered with beautiful roses, sweet peas and zinnias, surrounded by lush green grass and foliage.

Added to this idyllic setting was a lavish colonial lifestyle which included purpose-built officers’ clubs, large swimming pools, riding stables, tennis courts and cricket pitches. Military nurses in India worked extremely hard, sometimes in very difficult climatic conditions, but in peacetime they were able to revel in luxurious comfort. For Margot, India was everything she hoped it would be: colourful, exciting, interesting, spiritual and challenging. Professionally she was also very happy and acquired new technical skills by attending a specialist operating theatre course. Theatre nursing was an extremely stressful field of nursing and not all girls were up to the task. One young girl remembered that she approached her first days in the operating theatre with some trepidation: