Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

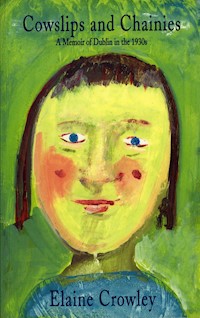

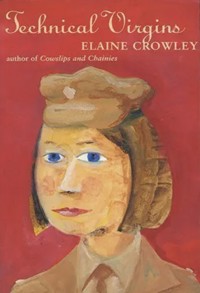

In her best-selling first volume of autobiography, Cowslips and Chainies, Elaine Crowley remembered her childhood in 1930s Dublin with great warmth and poignance. In this delightful sequel she recalls her years as a young woman serving in the British army ATS after the Second World War. This is a memoir of leaving disease-ridden Dublin for a world she imagined to be a Tír na nOg of the young and healthy; of being a 'Paddy' in England; and of passionate friendships and romances. With her inimitable novelist's eye for detail, Crowley weaves a fascinating tapestry of her years as a 'technical virgin', coloured by vivid descriptions of army rations (inedible), fashion (Maidenform bras, the miseries of the ATS uniform), social trends and sexual mores. Crowley re-creates a vanished world that will touch a chord in all who were once young.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 366

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Technical Virgins

Elaine Crowley

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

1945

The train, as if impatient to start its journey north, huffed and puffed its plume of smoke towards the station’s glass-panelled roof. The June sun shone onto the waiting passengers; onto the beady-eyed waddling pigeons searching for anything edible. The sun added to the discomfort of the sweating men loading the guards’ van: heaving into it sacks of mail, boxes, crates, packages and parcels.

Sweat beaded the faces of the porters carrying heavy expensive luggage towards first-class carriages. Young boys, dirty, unkempt, mitching from school, some barefoot, some wearing boots several sizes too big, touted less prosperous passengers. ‘D’ye want your case carried mister?’ they asked, wiping faces and noses with torn sleeves of their shirts and gansies. Giving the ‘ride on that till you get a pony’, salute to railway employees who threatened to kick their arses if they didn’t get to Hell’s Gates out of their way.

Around the station kiosk people pushed and shoved their way to the counter, bought newspapers and hopefully asked if there were any cigarettes ‘Are you coddin’ me?’ the assistant replied. ‘Sure for all the cigarettes that are about, the war might still be on.’

Not far from the kiosk a group of young girls in ill-assorted outfits stood close together. They wore faded summer frocks, too long or too short. Some had topped the frocks with costume jackets in serge, flannel and tweed, all with the appearance of having had a previous owner …

The girls were mostly pretty. Good complexions. Dark-haired and fair. Ginger and auburn. Straight hair combed up into sweeps secured with many clips, frizzy perms; and one girl with long straight blonde hair wore it in the style of Veronica Lake. Now and then with a toss of her head shaking it back to look up at the station clock. Around their feet were shabby cardboard suitcases secured with belts or pieces of rope. They talked loudly, laughed and giggled nervously. One, after glancing up at the station clock, began to cry. Her companions offered her words of comfort, cigarettes from paper packets of woodbines. Green packets decorated with honeysuckle. ‘Have a bull’s eye,’ one suggested and with difficulty prized from the depths of a newspaper cone a sticky hard-boiled black and white sweet. ‘Go on,’ she urged ‘take it.’ The girl sniffed and sobbed, then wiped her eyes, took a sweet and began to suck.

A little apart from the group two other girls and a woman stood. The woman wore a black edge-to-edge coat over a dusky pink dress and a black straw hat tilted becomingly over one eye. Her shoes were suede, good condition and high heeled. To the older of the two girls she talked earnestly. From time to time the girl nodded as if agreeing with what was being said. Expressions of irritation and embarrassment flitted across the other girl’s face.

The guard’s van closed. Passengers who had loitered now began to board the train. The woman threw her arms around the younger girl, held her close and kissed her. A railway employee walked along the platform slamming doors. The group picked up their suitcases and moved forward. One called to the others, ‘We’ll squash into the same carriage.’ The girl disengaged herself from her mother and followed them. At the end of the train a man waved a green flag. The train began its journey to Belfast.

one

Cheshire

In four days I had learned to answer to Paddy, Cock, Chuck, Kid and, occasionally, Cloth-ears. To dress and undress before twenty-three strangers. To make my bed on biscuits: to unmake and barrack it. To sleep in a room almost devoid of furniture, curtainless and cheerless. To eat for breakfast steamed fish, grey in colour, surrounded on the plate by equally grey water; leathery sausages with tasteless insides; reconstituted eggs, pallid and, whether served scrambled or as omelettes, flavourless and of a rubbery consistency; to drink hot, sweet tea brewed in urns as big as a washday boiler. Tea rumoured to be strengthened with washing soda and spiked with bromide to lull our sexual urges.

I had left my home in Dublin, gone to Belfast and from there sailed across the Irish Sea in a force nine gale, transferred to a packed train suffocated almost by smoke and smuts, then ridden in the back of an army vehicle and eventually arrived at my destination. At an army barracks in a Cheshire town to be trained as a woman soldier.

In Belfast I took the King’s shilling, signed on for two years and became a member of the Women’s Auxiliary Territorial Service. All this I did for love. Not for King and country but for the love of a man. A man I adored with all the love of my seventeen-year-old heart … my first and only love who could send shivers up my spine, make me feel faint, blush, tremble, lose my appetite and light candles to the patron saint of hopeless causes. For if ever there was a hopeless cause my love affair was one.

The object of my passion, hopes and dejection wasn’t aware of my existence. I loved from across the street, from glimpses in the chip shop, across aisles in mass. I watched him in the dance halls tangoing, fox-trotting in the arms of expert glamorous dancers.

I walked miles around the city hoping for a sight of him. Found where he lived and haunted the street. And on occasions when I saw him pretended great interest in the nearest shop window. Through it I saw how tall he was. How well built. His trench coat and soft hat … Like Humphrey Bogart only handsomer. Humphrey Bogart had an ugly face. My love looked like Victor Mature. I’d seen the flash of his white teeth, his big brown eyes.

In work I talked about him to anyone who would listen. I dreamt about him, wakening just as he was about to kiss me, declare his love. Closed my eyes and tried to sleep again, to recapture the dream. My mother said she thought I was run down. I might need a tonic. Or maybe I was costive. There followed an inquisition about my bowels. She promised a dose of opening medicine.

Sometimes, often, studying myself in the mirror I saw the reason why I didn’t attract him. I was tall for my age, lumpy, my nose was too long, my eyes too small, my hair lank brown, straight and cut as if a pudding basin had covered it while the shearing took place. And my breasts bobbed inside my jumpers. My mother promised to buy me a brassière. But like many of her promises it never materialized.

And then one day in a magazine the solution as to how I could captivate my love stared me in the face. I would go to England. Join the ATS. I was looking at a recruiting advertisement for the Women’s Service. Looking at the girl in her uniform. Tall and elegant, sleek blonde hair crowned by a perky little cap. Wearing an expertly cut tunic in fine barathea the colour of sand with the sun on it.

I would join up. The uniform would transform me. I’d come back to Dublin wearing it. I would meet him in my uniform the colour of pale golden sand. He would notice me for the first time. He wouldn’t be able to resist me. How could he? How could any man resist the look-alike girl in the recruiting poster.

My mind was made up. Nothing would be allowed to stand in my way. But because when I reached my decision I wasn’t eighteen, I needed my mother’s consent to join the forces. She reared up when I asked for it. ‘Go to England, that den of iniquity, well indeed you won’t put the fur of your foot near it. Women are being raped and murdered every day of the week over there. Given drugged drinks and cigarettes and sold into the white slave traffic. And that’s apart from the bombs showering down on them blowing them to smithereens. What put that idea into your head?’

She wouldn’t understand or sympathize with unrequited love. So I pleaded lack of job satisfaction. ‘I hate tailoring. I’m fed up day in day out machining sleeve linings.’

‘Who likes their work?’ she retorted. ‘You think of no one but yourself … I moved out of the scheme after your daddy died to make life easier for you. We’re back in the street. I’m just getting back on my feet and you want to clear off … Well you’re not and that’s that.’

I pleaded and coaxed, ranted and raved. She countered all my tactics with gruesome accounts of atrocities committed in England. Charles Peace, Burke and Hare, Buck Ruxton and when the list of ordinary murderers ran out, there was Henry VIII, his daughter Elizabeth and Cromwell.

‘Prostitutes, whore masters, murderers and pagans the lot of them, you’re not going and that’s that.’

‘My daddy was English.’

‘The Lord have mercy on him, his mother was Irish and a Catholic.’

‘And in any case in two months I’ll be eighteen and won’t need your letter,’ I said when she stopped for breath. For a moment she was at a loss for words. But only for a moment. Then back she came, ‘You always were a self-willed little bitch. I haven’t forgotten when you bought a coat unknownst to me.’ My beautiful heliotrope-coloured coat. We seldom had a row that she didn’t remind me of the deception I had practised to get it. ‘No thought for anyone but yourself,’ she continued, soothing a brown paper bag. She smoothed and saved brown paper bags and bits of string. ‘How am I going to manage without your £1 a week coming in, answer me that?’

‘You’re a widow. You’ll get a dependant’s allowance. It says so in the forms.’ I’d slipped up.

She pounced. ‘What forms?’ Her eyes bored into me. Before their gimlet gaze I couldn’t lie.

‘I sent for them. It’s all there about the allowance in black and white.’ Black and white was a favourite phrase of hers. She had great faith in the written word.

Putting on her Woolworth’s glasses many times reinforced with other wire, she took the forms I produced. ‘They write in Double-Dutch,’ she said as she perused the paragraph dealing with allowances. Her lips formed each word silently as she read.

I watched her filled with elation as I did so. I was free. I was escaping. Then suddenly I was deflated. What was I doing? What was I letting myself in for? Why was I leaving home?

‘To escape from her,’ I told myself. ‘No more rows, no more nagging. Come and go as I pleased. Make new friends, see new places.’

Her lips were still working over the letter’s official jargon. She appeared to have shrunk. She looked like an old woman. Seeing her like that I remembered the day after my father’s funeral when I came home from work and she was sitting at the table looking like an old shrunken woman despite the black mourning clothes suiting her. Huddled and dejected fingering the pound notes spread on the table.

‘Every undertaker’s yard in the city collected for your daddy. He was very well liked. Lord have mercy on him—the comfort I could have given him with half of that. D’ye know what I was doing when you came in?’

‘No.’

‘l was just thinking—I have everything. Everything I ever wanted. A house and all that money. Everything I ever wished for. Everything—and I’ve nothing for I haven’t got him.’

That day three years ago I sat and cried with her. Not for long. She never cried for long and in any case there was my dinner to dish up. Instead she reminisced about when she’d first met my father. The handsomest, smartest soldier in the British Army, and after the Treaty when he transferred to the Free State Army the smartest one in that.

‘People,’ she said as she teemed the potatoes into the slop bucket, ‘used to stop to look after him in the street.’ She put the pot back over a low flame and continued talking, shaking the pot as she did so. ‘They’re nice and dry now. What was I saying? Ah, yes, about how smart he was. He was a great horseman as well. Could ride from when he was child, his grandfather in Horsham kept horses.

Sometimes in between jobs in the undertakers he’d get work in the riding school up in the Park. Bridie in the Iveagh Market used to keep the breeches and leggings for me. He liked to knock about with the horsy crowd in Queen Street. D’ye remember him in the breeches and leggings?’

‘Yes,’ I said, my voice choked with tears I was trying to repress.

Choked with sadness and the guilt of a day’s memory a few years before he died. I must have been about eleven then. I was coming out of school as the 83 bus stopped at the terminus on Cashel Road. And my father stepped down from the platform. He was drunk and I tried to avoid him spotting me. But he did and whistled his melodious whistle to attract my attention.

He was staggering slightly and his bowler hat pushed to the back of his head. I prayed silently for the ground to open and swallow him up before any of my pals would see him. It didn’t and he came to me and embraced me. Asked as he always did how I had got on in school. Had a treat in his pocket for me—a penny bar of chocolate.

‘What has you in bad humour—that’s not like you,’ he said, taking my hand in his. I mumbled an excuse and we walked on, me imagining everyone from school watching us and nudging each other. ‘Look at her oul’ fella, mouldy drunk,’ they’d be saying. During the walk home for the first time in my life I hated and was ashamed of him. But at the same time would have scrawbed the face off anyone who dared to pass a remark on him.

The dinner was ready. I sat to the table for it. And only referred to remembering well my father in his riding breeches. Putting the lamb chop on top of the cabbage so the meat juices would flavour it I my mother said, God help him, he worked for six years dying on his feet. His chest, you know, it was always delicate.’

Even after having seen his death certificate and numerous doctors confirming the diagnoses of tuberculosis, she would never admit that’s what he had. There was a powerful stigma attached to the disease. You were often shunned. As AIDs sufferers are today.

She continued to reminisce. ‘Months before he died he volunteered to go into Our Lady’s Hospice for the Dying. He did that,’ she said, ‘for our sake. So the bit of food would go further and his cough wouldn’t disturb us during the night.’

Then her memory switched to happier times. And she and I recalled him dancing a jig, tapping out tunes on the oven door and asking us to guess what they were. Planting his garden. Robbing the granite doorstep from the budding site and with superhuman strength lifting it onto the baby’s go-car. Getting it back to the house, even up the steps, and into the back garden. It was to have been used to make a rockery. But his strength was used up then and forever. The granite could not be broken and the step remained where it had been dumped and was used as a seat.

My mother’s moods changed like quicksilver. Suddenly the pleasant reminiscences were done with. ‘D’ye know,’ she said, ‘you’re a bloody little bitch. I searched high and low for my scissors all day and couldn’t find it. Where did you put it?’

She could go on for hours like this if I didn’t produce the scissors. Which I couldn’t. And now there was no daddy to either defuse or deflect her. These were the times when I missed him so much.

I was only fifteen. Life outside the house beckoned me. I promised I’d search for the scissors when I came back but first I had to call to a friend’s house. I wouldn’t be a minute.

‘Have a cup of tea before you go,’ she said. There was neither spite nor vengeance in her nature. I was never what is now called grounded, never confined to my bedroom, never deprived of food. All only talk, talk, and idle threats to kill, cut the legs from under you or break your neck.

When I came back she was as likely to be telling or reading my sister a story, having a row with my brother, or one of her women friends might be there consoling and crying with her, or giving out yards about the next-door neighbour.

That’s how our life was. The three years since my father’s death hadn’t altered it. He was missed and cried over, laughed over and never for a day completely forgotten. It was a house of warmth and forgiveness. A house of love and safety. A house where although you might consider yourself grown up my mother would still lash out with her hand. And later in the night when you were just falling asleep, she’d tiptoe into your room, adjust the bedcovers and sprinkle you with Holy Water while she murmured prayers to bring you safely through the night. More often than not the water fell on your face and woke you up.

And here I was now eighteen and about to leave it all. The abiding love, the security. A mother who was always there for you. Who’d stick up for you. ‘My child’, as she said about each of us in turn, ‘wouldn’t do such a thing.’ But if you were in the wrong you’d be chastised. Who above all was so forgiving. Who forgave my father when he confessed he had been unfaithful to her. Who tracked down his paramour and put an end to their affair. And forgave him when he discovered that she had visited his lover and beat my mother up.

My mother who was the cranky, joyous spirit of our home and hearts. Who nursed my father until he went into the Hospice. Who walked there in hail, rain and snow. The piece of cardboard covering the hole in the sole of her shoe sodden and squelching. Who had three children as volatile a strong-willed as she was and fought her every inch of the way when her mood was quarrelsome. Though looking back now I suppose it was the response she wanted.

How could I leave all this? Go amongst strangers? Enter a world I knew nothing about? Who would slip a hot jar beside my feet when they were cold? Draw a boil to a head with the heated neck of a bottle? Make me thin gruel with a teaspoon of whiskey in it when I had a cold? Make me a ‘guggie in a cup’ if I was off my food?

These memories and thoughts chased each other through my mind as she finished the letter. She took off her glasses, put them in the pocket of her pinnie and the letter on the mantelpiece. While doing so she noticed the time. ‘God!’ she exclaimed, ‘it’s after six if I don’t hurry I’ll miss the paperman and I’m follying up that murder trial’

She had her coat on and was out the door in a flash. I heard the front door slam and life beckoned to me again. My mother would be all right. I’d be all right. We were survivors.

I got the letter of consent and went to Belfast for an interview and medical examination. On the train I met several girls also hoping to join-up. In the barracks to which we reported I saw khaki uniforms for the first time. They looked nothing like the one in the recruiting poster. The colour wasn’t a goldy sand colour. More like the dictionary definition which I had looked up: ‘Of Persian or Urdu origin, meaning dusty’. These uniforms were drab and dusty, but I consoled myself it was age and long wear. Mine, the one in which I’d cause a sensation in Dublin and captivate my love, would be dazzlingly new.

* * *

‘Childhood illnesses?’ the medical officer asked. I listed them whilst my heart was thundering with fear as I anticipated his next question and the lies I must tell.

‘Parents living?’

‘My father’s dead.’

‘What did he die of?’

‘An accident, sir, he was knocked down and killed.’

My mother had tutored me well. Never, never, and especially to a doctor, did you admit that there was tuberculosis in your family. There was a stigma attached to the disease. As a relative of the infected person you felt the guilt and shame. Euphemisms were used. A touch delicate, asthma, a weakness left over from a childhood pneumonia or pleurisy. Employers sometimes refused you work. Parents put between courting couples with consumption in their families.

During the seven years my father had the disease my mother admitted to no one, not even herself, that tuberculosis was what ailed him. All his X-rays, positive sputum tests, weight loss, fever-flushed cheeks, night sweats and racking cough didn’t convince her. Not even his death certificate on which the cause of death was given as phthisis. ‘Look,’ she said, pointing to the Latin word of Greek origin for a wasting disease, especially tuberculosis. ‘Wasn’t I right all along? I knew he never had consumption. That’s what killed him,’ she said pointing to the unpronounceable word. ‘That little cur in the Meath Hospital didn’t know his arse from his elbow. Probably out of the College of Surgeons.’

She had tutored me well. Blatantly I lied to the medical officer, elaborating on the accident that killed my father. For she had warned me, ‘Once you admit to a doctor about consumption they’d start prying and probing. Sending you to clinics for more probing and X- rays. Shadows, patches, things you were unaware of and didn’t interfere with you might be discovered. Then you were in their hands. Your body never your own again.’

My lie was accepted, my heart, lungs and liver declared sound. I was passed Al and given a date on which to return and sign away my freedom. And so on 17 June 1945 I came to the camp in Cheshire.

The people in the tailoring factory made a collection. Thirty shillings, I think. More money than I had ever owned before. From it I bought my first deodorant. A push-up stick of O-Do-Rono. The owning and using of it made me feel grown up and sophisticated. I had presents from relations. A short-sleeved, maroon, hand-knitted jumper, a rosary and a prayer book. A change of clothes, still minus a brassière, and my beautiful coat. Cream and green tweed, made to measure with a dark-green velvet collar. There were always tailors in the trade who did ‘nicksers’, using the firm’s time and often their trimmings as well. That’s how I came by the coat. Apart from those possessions, the only other items I owned were toothpaste, a toothbrush and a comb.

My mother came to see me off. She looked very smart in her edge-to-edge coat. After sizing up a group of girls who were travelling with me to Belfast she singled one from the crowd. A Dublin girl whose name was Deirdre, stout, rosy-cheeked and, in my opinion, years older than me. My mother talked in a voice she used in public, especially in the presence of men, laughing her lovely laugh. Now and then looking round to see if anyone was paying her attention.

I was mortified and prayed for the train to soon leave. When it did she followed it along the platform, still talking, advising, waving, tears falling which she dabbed at with a dainty handkerchief. I, too, leant out of the window waving until the train turned a bend and to my great relief took me out of her sight.

two

It was the effect of the injections against smallpox and varieties of typhoid fever: I hadn’t recovered from the journey. I was disorientated from the numerous and confusing experiences since I’d arrived in the camp: punch drunk with the amount of slang and army jargon. Biscuits were three-piece mattresses: barracking was a way of sandwiching your sheets between two blankets then wrapping the lot in a third so that the bundle resembled a monster brown-and-white liquorice allsort. Rookies and jankers, fizzers and bulling, knickers called wrist stranglers. My mind was unhinged. It must be. I was hallucinating. For why else everywhere I looked did I see pairs of naked breasts. High round ones, slack pendulous ones, pert tip-tilted, minute to the point of non-existence. It wasn’t modest to look on another’s nakedness. According to my Catholic rearing it wasn’t modest to look on one’s own. And not having a full-length glass at home, I never had.

I looked away. I shook my head to clear it. I had a fever that was it. I was delirious. I looked back again and the breasts were still there and naked women splashing water at each other, laughing and singing, ‘In a strange caravan there’s a lady they call the gypsy.’ And then I saw the strangest sight of all. A pair of widely spaced breasts and growing in the space between a bunch of curly ginger hair. Banging her chest, the owner of the breasts began doing Tarzan imitations, then yelled, ‘What d’ye think of the running water, Pad?’ her voice rising above the singers. ‘Eh, cloth-ears it’s you I’m talking to.’

‘Me?’ I shouted back.

‘Yeah, you chuck. What d’ye think of the running water, great isn’t it?’

My head cleared. I wasn’t feverish nor having hallucinations. We were having a communal shower, something I’d never experienced before. And I was cloth-ears, Pad and chuck. The wide-spaced breasts and chest hair were Edith’s … also a new recruit, a rookie, but the daughter of an old soldier who showed us the ropes. Covering my nakedness with an army-issue towel (‘for the use of’, a phrase I didn’t, and never did, understand) I stepped onto a duckboard and called to Edith, ‘The water’s great.’ I had answered in the same vein to how I found wearing shoes, what I thought of electricity, flush lavatories, buses and trains. Recognizing from the good-humoured voices that asked the questions that neither malice nor antagonism was intended.

‘You’re alright Pad,’ Edith assured me while pulling on her khaki knickers with well-elasticated legs. ‘Pity the bugger who tries to get his hand up these,’ she laughed and braless went to a shelf where she had left her cigarettes. ‘Want a fag kid?’ she asked, proffering a packet of Park Drive.

‘Ta,’ I said using the word for the first time in my life.

* * *

For four days we had been confined to barracks. During this time our uniforms were issued and injections and vaccines given. We spent the days nursing sore arms and marking kits with our names and numbers: meeting Corporal Robinson our squad leader and getting to know each other.

Twenty-four girls occupied the barrack room. Half were from Cheshire and Lancashire, the other twelve those who had travelled up from Dublin with me.

On the way back from the communal shower Edith reminded us that tomorrow for the first time we would wear uniform. ‘We’ll get started on the bulling after tea.’

Already I had taken a great liking to Edith and to her friend Marjorie. They came from the same seaside town and had been friends all their lives. They were both low-sized, stocky; they resembled each other except that Edith’s hair was ginger and curly like the hair on her chest, and Marj’s blonde with dark roots and permed. They were good natured and funny. I found it difficult to understand their dialect but was learning. I would have liked to ditch Deirdre, my minder, but wherever I went she was close behind.

After dinner we could unbarrack our beds, lie or sit on them, get under the covers and sleep. Anything we liked provided no one else shared the bed. This had been stressed at a lecture on the day after we arrived at barracks. ‘It’s an offence for which you can be charged,’ the officer informed us.

Afterwards Edith answered our questions as to why you could be charged. ‘You know how some fellas’d do a frog if it stopped hopping, according to my Dad there’s girls like that too.’ We gasped in disbelief. Fellas maybe, but girls? Then one of the Irish girls said, ‘I’ll tell you one thing, no one will lie on mine. All my life I slept two or three to a bed. Sometimes four. Two at the top and two at the foot. It was nothing to wake up with my granny’s big toe nearly poking my eye out. Separate beds are gorgeous, so they are.’ The majority of us having been reared in the same circumstance agreed with her.

We lounged on our beds, we smoked, talked and I, eager to familiarize myself with army slang, quizzed Edith. ‘A charge’, she explained ‘is the same as a fizzer.’

‘Why d’ye get put on a fizzer?’

‘All sorts of things. Being late on parade, not barracking your bed properly, insubordination, talking back, coming in after roll call, belting an NCO or Officer, millions of things. She recited a long, long list of offences which carried sentences that varied from forty-eight hours confined to barracks, Jankers, which she explained might be cleaning rooms, bumpering floors or kitchen fatigues. ‘That’s peeling sacks and sacks of spuds.’

Edith now had a captive audience and continued. ‘For some things you could have your pay stopped or even finish up in the glasshouse.’

Marj contradicted her, ‘Hang on cock, you’re talking about soldiers. Women don’t get sent to the glasshouse.’

‘Maybe I’m wrong about that’, Edith conceded, ‘but not about nothing else.’

Bubbles, the only girl in the squad who owned a dressing-gown and spoke like the BBC newsreader, and Corporal Robinson, and whom Edith had nicknamed because her hair was like the picture advertising Pear’s soap of a boy blowing bubbles, asked Edith, ‘What is the Glasshouse?’

‘Military prison. Terrible place. No food, only bread and water. Get flogged if you look crooked, so my Dad says.’

‘Sounds like something out of Dickens,’ Bubbles said in a voice that cast disbelief on Edith’s statement.

‘Clever clogs. If you don’t believe me don’t ask questions in future.’

‘Sorry,’ said Bubbles who didn’t seem sorry at all. But adroitly changed the conversation and talked about the following day, how we’d fare during our first session of square bashing which Edith had informed us was slang for drilling on the square.

‘I’m petrified just thinking about it,’ Deirdre said. I hope there’ll be no fellas watching us.’ According to her she was so shy and retiring that almost everything terrified her. But not, I said to myself, strange fellas on boats. And while the girls discussed the pros and cons of drilling on the square my mind went back to the night we had crossed from Belfast.

A force nine gale was blowing. People started to vomit as soon as the boat left the harbour. The stench was overpowering. Deirdre said she couldn’t bear it. She needed a blow of fresh air. I catnapped and eventually fell asleep. I slept for more than an hour. There was no sign of Deirdre. I went to look for her. Passing a bar I thought I saw her white swagger coat. But when I pushed open the door the smell of stout hit me like a malodorous wave and I let the door close.

Here and there as I wandered about the ship, now and then steadying myself against the walls as it lurched, I saw girls we boarded with and asked if they’d seen Deirdre. No one had. Eventually I reached the deck. The wind screeched and spray washed over the boat’s side, fell onto the deck and drained into the scuppers. Maybe, I thought, Deirdre fell overboard. I’d have to find a seaman and report her missing. I found the wind exhilarating. The fresh, salt-laden air was gorgeous after the revolting smells in the lounge. Now and then I stopped my lurching along to lean over the vessel’s side and watched the wake of the ship spin out behind it like yards of silk, a frothing mass of white in the darkness of the night.

There were other people leaning over the rail. One, a man quite near me. I heard him retch but knowing nothing about the winds direction stayed where I was until a plaster of his vomit blew onto my cheek. My stomach turned and I almost threw up. took several deep breaths, moved far from him, then took my scarf, already wet with spume, and wiped my face. I let the wind take the stinking scarf, wet a handkerchief in the scuppers and scrubbed my cheek and then let the handkerchief follow the scarf. All thought of a drowned Deirdre had left my mind. I was cold and shivery. I’d have to go back inside or find a sheltered place. The walking warmed me and once again I began to enjoy the storm, feel courageous braving the elements, let myself go with the pitch and roll of the ship convincing myself I was a natural-born sailor. I was beginning a new life. A marvellous exciting life. For wasn’t it the middle of the night, dark, stormy, and I savouring every minute of it. I remembered heroines I’d read of who’d been connected with the sea … Grace Darling, Graine. Graine sailing with her father, an O’Malley , a slip of a girl. A pirate plundering the ships of her enemies and Grace risking her life to save the lives of others. I could be such a woman. There was nothing I couldn’t do. I stood gazing at the tumultuous sea lost in my fantasies, my hair clinging to my skull, water dripping into my eyes, the shoulders and front of my coat saturated. I began again to shiver. But knew that I didn’t want to go back to the crowded saloon, smoke filled and reeking of vomit. Not yet anyway. I walked again looking for shelter and came near the funnels. Behind one I’d be out of the wind and warm. I moved closer and then I saw them. A couple. A man and a woman. Her white coat and other clothes above her waist. The man holding her.

I could hear him grunting as he appeared to be trying to push her through the funnel’s side. I had a vague idea of what they were doing. Was certain it was Deirdre and instinctively knew neither would welcome a greeting or me expressing relief that I had found her.

I made my way back, pushed open the heavy doors telling myself I would have to endure the lounge. Exhausted by this time, I fell asleep squashed between a man and a woman reeking of porter and slept until the boat docked. There was great activity. People looking for children, cases, and trying to guess where the gang-plank would be attached to the ship. I met up with the girls who were travelling with me to join the ATS. Then Deirdre pushed her way through the throng and berated me. ‘I’ve been looking for you all night,’ she smelled of drink. ‘I was worried and after me promising your mother I’d mind you. Will I get you a cup of tea, they’re still open?’

‘That’d be grand,’ I said and watched her go, seeing at the same time in ray mind’s eye, the white coat hoisted above her waist. She brought the tea. We waited to disembark. She didn’t say anymore about her search for me. And I said nothing about my stroll on deck.

‘Right then, let’s be having you,’ Edith’s voice put an end to my thoughts about Deirdre’s escapade. ‘Let’s get a bit of shape on these bloody uniforms.

‘Let’s leave it till after tea,’ Marj suggested, and several voices agreed with her.

‘We could do a lot in a hour,’ Edith said, but she was outvoted. We lounged and smoked and talked. Mostly about food. The English girls longingly recalling meals before the war. The roast Sunday dinners, home-made steak and kidney pies with suet crusts, liver smothered in onions, real eggs, banana sandwiches, tomato sandwiches, oranges, and bacon butties with lashings of tomato sauce.

In Ireland only tea was strictly rationed, and I’d only left Dublin four days ago. So neither I nor the other Irish girls expressed longings. Though I did think how nice two lightly boiled eggs and a fresh Vienna roll would be at the moment.

The English girls were remembering when sweets weren’t rationed. How every time they had money they bought sweets and chocolate. Crunchie bars and Tiffin bars, Fry’s Cream chocolate, acid drops, Dolly mixtures, Liquorice All Sorts and sticks of Liquorice. They went on remembering and planning what’d they’d buy when rationing ended.

The teatime meal differed only slightly from breakfast. An inch cube of butter and a dessertspoonful of jam instead of margarine and marmalade. We went to the cookhouse carrying our knife, fork, spoon and enamel mug. There with the other squads in training we queued for the counter and the aluminium sunken wells where vegetables, stews, whatever of that nature on the menu was served from. One of the first things I noticed about some of the food was how it differed in colour to food at home. Greens, as they were called, hadn’t a trace of green about them but were a blend of yellow, white and grey. Brown gravy was a shade I would have described as buff, beige or fawn. Brown stews were brown but the first mouthful and your palate recognized the artificial flavour. And when on rare occasions roast beef, pork or lamb was served, it too was a colour I didn’t associate with such meats and was tough, fat, full of gristle and tasteless.

For tea we were served ‘toad in the hole’, two sausages buried in a mass of doughy batter. I had never before seen such a dish. It was something my mother would have described as a plocky dollop. But hunger is good sauce. And we were hungry. The plates were left as clean as Jack Spratt and his wife’s. We refilled our mugs with tea to take back to the barrack room while a khaki-overalled orderly whose curlers made lumpy bumps beneath her turban waited to remove the urn. Outside the cookhouse we washed our cutlery in the barrel of hot water provided. Its surface shiny with grease. Preparations for the bulling of the uniforms began as soon as we were back in our room. ‘Right then’, said Edith, ‘someone put the ironing board up. Get out your brasso, shoe polish, button sticks and two sanitary towels.’

‘Sanitary towels, what for?’ asked someone.

‘For putting on the brasso and polish. You’ll want your dusters and brushes, shoe and button ones, as well.’

Sanitary towels were Lord Nuffield’s gift to the Women’s Services. They were expensive to buy. At home many girls used rags kept for when they menstruated. Washed and rewashed for many months. Sanitary towels were a luxury item and I’d never known them to be used except for the purpose they were intended. But soon I became used to ripping them apart. Using the cotton wool for applying brasso, polish, cosmetics, cleaning windows. And once many years after joining up I visited a soldier in hospital who had had a throat operation: around the wound on his neck and draped by the loops over his ears was a sanitary towel. He hadn’t long come from the recovery room and so probably wasn’t aware of the incongruous dressing. I was mortified with embarrassment for both of us. And at the same time wanted to giggle.

* * *

Edith showed us how to spit and polish. A mouthful of spittle into the Kiwi Dark Tan, a ball of cotton wool to blend the two. Then the corner of a cloth wound round the index finger dipped into the tin and then the tedious circling and circling of the shoe’s surface. From time to time moistening the polish again or spitting directly onto the leather until the faintest of shines appeared.

‘You’re lucky you aren’t blokes,’ said Edith, pausing to inspect our achievements. ‘You should see the men’s boots the first time they’re issued. Rough as a badger’s arse they are. Have to be soaked in piss.’

Not sure if this wasn’t another Paddy joke, I gave her a quizzical look.

‘No kidding. I’ve seen new boots and me Dad told me. Keep a bucket in the barrack room and piss in it then dunk the boots. Softens and brings the leather up a treat.’

I spat, circled and rubbed until my arm ached and my finger felt paralysed. Everyone felt the same and it was decided to call a halt.

Corporal Robinson came into the barrack room and enquired if we were all right. Were there any problems. After she left I said how pleasant she seemed. Edith contradicted me. ‘Wait’ll she gets you on the square it’ll be a different story. She’s still treating you like a civvy. Wait’ll she gets you in uniform.’

The uniform. Momentarily I’d forgotten it. Forgotten my bitter disappointment on the day my kit was issued. A mountain of it. More clothes than I had ever possessed in my life. Three brassières, two corset belts, three pairs of khaki directoire knickers—the ones Edith called ‘wrist stranglers’—three pairs of short white woollen panties, two pairs of blue-and-white striped flannel pyjamas. Three pairs of thick stockings the colour of diarrhoea. Two pairs of shoes, one pair of Plimsolls, baggy brown shorts, a burnt-orange shapeless sports shirt with a brown trim. Needles, threads, buttons in a small cotton bag called a ‘husive’. Shirts with separate collars, a khaki woollen long sleeved v.-necked pullover, cap, jacket, tunic, skirt and greatcoat.

A uniform that looked as if it had been made from a rough woollen blanket. And bore no more resemblance to the girl’s uniform in the recruiting poster than I to her. But I fervently believed that wearing what she was wearing I would be transformed. I would go home to Ireland wearing it and dazzle my love. Now I imagined the sight I’d be. The rough thick cloth, no perky little cap. The one’s we’d been issued with had brims and yards of sticking up crown. And all the shade of the vile stockings.

A lump rose in my throat. One always did when I was about to cry. And in seconds I was crying out loud. I’d done it all for nothing. There would be no triumphant return to Dublin in a glamorous outfit. With my tail between my legs I’d go back in the green tweed coat for I wouldn’t be seen dead in that tunic, skirt and chef’s peaked cap. Soon I had a crowd round me. Everyone full of concern as I tried between hysterical sobs to tell Edith of the tragedy that had befallen me. ‘I thought I’d look lovely. And then he’d notice me. And fall for me. He would, I know he would.’

Out I blurted everything. About the poster and the one I loved for so long. My one and only reason for joining up.

‘Pad’, she said, ‘you’re daft as a bleeding brush. Haven’t you ever heard of de Valera?’

‘What’s he g to do with it?’ I asked, sobs still threatening to choke me.

‘He’s that long drink of water with the specs.’

‘I know what he looks like.’

‘Yeah, well, he’s the one who wouldn’t let us have your Ports. Kept you out of the war. Ireland’s neutral. So even if the uniform was a dead ringer for the one in the magazine you still couldn’t wear it.’

‘But why?’ I persisted.

‘You can’t wear the uniform of a country at war, in a neutral one. You could be shot. Slung in prison camp.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Positive. And listen, kid, forget about the fella. You’ll meet hundreds over here in the army camps. Fighting them off you’ll be.’