Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

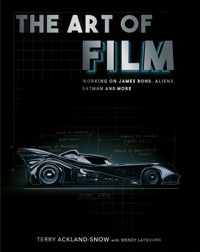

'Tim Burton came in and commented, "Great, but how do they get in the car? There aren't any doors!" Sadly, I hadn't thought of that.' *What do *On Her Majesty's Secret Service, 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Great Muppet Caper have in common? **Terry Ackland-Snow worked on them, that's what. In The Art of Film, Terry lifts the lid on his extraordinary career, from being held hostage by a wannabe film crew in Jamaica to forgetting to add doors to the Batmobile. It is an insight into a lifetime of working in the film industry, mixing the amusing anecdotes with revelations about just how the magic in these movies was created. With over 200 images, including set sketches and design plans, this is a book no film aficionado should be without!**

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 178

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Jacket illustrations:

Front: Plans for the Batmobile.

Back: Diagram of the layout for the cable car scene in On HerMajesty’s Secret Service.

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Terry Ackland-Snow, Wendy Laybourn, 2022

Front cover design © Nicky Ackland-Snow, 2022

The right of Terry Ackland-Snow and Wendy Laybourn to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9991 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Turkey by Imak

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

In memory of my brother, Brian Ackland-Snow, 1940–2013.

At the time of his death in 2013, my brother Brian hadn’t worked for fourteen years due to the cruel illness Alzheimer’s Disease. However, his humour, compassion and generosity still shone through. He was a very unselfish man, both in the workplace and as a husband and father.

Brian loved drawing, art and model-making from an early age but, at our father’s insistence, he had to complete a carpentry apprenticeship with the family business before he started in design. After this he joined the art department at the Danziger Studio in Elstree as an assistant; his first film was The Road to Hong Kong at Shepperton Studios, where he worked for production designer Roger K. Furse.

He went on to work on many films and television programmes from 1962 until he retired, winning an Oscar in 1987 for Best Art Direction, a BAFTA for Best Production Design for A Room with a View and a Primetime Emmy for Outstanding Individual Achievement in Art Direction for the miniseries Scarlett.

Brian’s film and television credits include Without a Clue, A Room with a View, Superman III, The Dark Crystal, McVicar, Dracula, Death on the Nile, Cross of Iron, The Slipper and the Rose, There’s a Girl in My Soup, Battle of Britain, 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Quiller Memorandum, The Road to Hong Kong, The Magnificent Ambersons, Animal Farm, Kidnapped, Scarlett, Cadfael, The Man in the Brown Suit and Hart to Hart.

CONTENTS

Forewords

Preface by Wendy Laybourn

Acknowledgements

Terry Ackland-Snow’s Film and TV Credits

Introduction

ONE

Trainee to Draughtsman

TWO

Draughtsman to Art Director to Production Designer

THREE

Draughtsman and Art Director

FOUR

Art Director

FIVE

Art Director and Production Designer

SIX

Art Director and Supervising Art Director

SEVEN

Production Designer

EIGHT

Films That Didn’t Make It to the Screen

NINE

A Few Technical Explanations

FOREWORDS

Michael G. Wilson and Barbara Broccoli

Terry’s first job for us was draughtsman for On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969) and, several years later, we were lucky to work with him again as an art director on location for The Living Daylights (1987), as well as with the late production designer Peter Lamont.

We are delighted that Terry’s extensive career has led him to share his film-making passion through his courses at Pinewood Studios, training our next generation of art department creatives.

John Glen

I first met Terry Ackland-Snow when filming On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and our paths have crossed many times since, lastly on The Living Daylights.

When I look back, apart from throwing the best Christmas parties, the art department are the unsung heroes of the Bond movies. I remember filming in the desert and needing a towering bridge to carry away the fleeing horsemen and pursuing tanks. It doesn’t rain very much in the desert, so an unimpressive structure across a small wadi was transformed by a foreground miniature into a bridge 90ft high with a silica river flowing beneath.

The miniature was built at Pinewood Studios and transported to Morocco so, with the aid of a nodal head camera mount, we were able to pan and zoom to capture the action taking place on the bridge, together with explosions.

This remains one of my very favourite shots and a lesson to any would-be film director.

Chris Kelly

Making movies for the cinema or television is a team game. No other form of art or entertainment calls for such a wide range of skills. Take a look at a film crew on location and you’ll be staggered by the number of vehicles and personnel. Do they really need all those people? Yes, is the answer. Every member of cast and crew has a vital part to play. All the glory goes to actors and directors but where would they be without an army in support? Producers, line producers, writers, directors of photography, lighting, sound recordists, production designers, costume designers, make-up, all with their own mini-departments, props, editors, carpenters, painters, accountants, caterers, drivers … I could go on. Increasingly, over recent decades, an additional creative development has totally transformed the images we see on the screen: VFX (visual special effects generated on computers).

No one in the British film industry is better qualified to take an overview than veteran production designer (art director) Terry Ackland-Snow. Designer of dozens of films, from blockbusters to intimate dramas, he now runs successful courses at Pinewood, passing on with characteristic generosity the techniques he’s learned over a long lifetime, which included earning a university doctorate in the process.

It’s no secret that in film and TV large egos are not uncommon. Happily, Terry doesn’t suffer from one. Having had the privilege of working with him over many years, I can vouch for the fact that he is invariably modest, unflappable, professional and endlessly inventive. In a word, he’s the ideal guide.

PREFACE

BY WENDY LAYBOURN

Terry Ackland-Snow has been dealing with the art of illusion for his entire working life and, no, he’s not a member of the Magic Circle. He’s an art director and production designer in feature film production. Throughout his long career he has worked on more than eighty films and one or two well-known television series since he started in the industry as an apprentice at the age of 16.

In the Collins English Dictionary, illusion is defined as a ‘deceptive impression of reality’ and in film production this definition is more relevant than you would think. The art department follows whatever style is required to construct the right backdrop for the performers and the rest of the production crew to work with, creating the ‘illusion’ that sets the scene for the audience. Sorry if this spoils your viewing experience but whatever you see on the screen, no matter how real it looks, isn’t necessarily what you think it is. It’s all down to the smoke and mirrors created by the art director and their team.

Film technology wasn’t originally meant to be used for artistic expression but began simply as a commercial extension of live theatrical events, recording the action on stage much like the modern documentary. However, the practitioners soon found that portraying a story on screen was quite different from a theatrical production as there are so many tricks available to film makers that are impossible to achieve on stage.

So, what is an art director? They are essentially the project manager of the art department and work directly for the production designer. They need to have a good eye for decoration and detail and the ability to think visually, to conceptualise ideas and to bring these ideas into tangible form. Not only do they have to use their creative and technical talents in the drawing office but, as they are fully responsible for the construction of the set, they also need a good working knowledge of building materials and architecture, a full understanding of the construction crew’s skills and the ability to manage the art department’s not inconsiderable budget.

Art directors are artists who can adapt their style to any number of different types of production. They integrate themselves and their team into the mood and feeling of a particular project, whether it is a comedy, a musical, a costume drama or a science-fiction extravaganza. They adapt to the range of materials and the scope of the design, which will test their imagination and skills to the utmost.

Film sets have developed through time from the painted canvas backcloths used in theatres to their present and highly sophisticated form. When film was in its infancy it was essentially just a series of animated photographs but then the showmen stepped in to work with the photographers and began the process of what is now taken for granted as film production.

However, the essence of film making hasn’t really changed since those early days. Although the early film makers were working with very basic and unsophisticated equipment and materials, they still managed to create memorable illusions and stunts with simple but often death-defying ‘in-camera’ effects. The creativity of the modern crew and their passion for telling the story are the same as ever; it’s just the technology that has grown over the decades so that the tricks and scenic illusions have become more and more exotic, making the seemingly impossible now a practical reality.

Each year the development of technology and visual processes make film sets more exciting and the learning process never ends. The film crew is like a mobile and ever-changing life force, so even the most experienced art director will find each new project a challenge!

In this book Terry will take you through the stories behind some of the films he has worked on, as well as often explaining how a particular effect or illusion was produced. If you find that you’re not quite sure about some of the techniques, check out Chapter 9, where he has described some of the technical stuff in more detail. We hope you enjoy reading this book as much as we’ve enjoyed putting it together.

Wendy Laybourn

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Within this book we acknowledge all who are sadly no longer with us but who, through their outstanding innovations from the early days of film design to the present day, have left their legacy for the benefit of all film makers.

Special thanks to the following for their contributions: Michael Wilson, Barbara Broccoli, Chris Kelly, John Glen, Robin Vidgeon BSC, Malcolm Stone, Ray Stanley, Emma Farke, Carol Ackland-Snow, Keith Ackland-Snow, Alexandra Kerr, Dusty Symonds and Ann Tricklebank.

Thanks to the following for illustrations:

Warner Brothers: Batmobile

Universal Studios

Henson Productions: Muppet storyboards

MGM: James Bond

Disney Art Department: Dark Crystal and Labyrinth

EON: The Living Daylights

Columbia Pictures: The Deep

20th Century Fox: The Rocky Horror Picture Show

Paramount Pictures EMI: Death on the Nile

Rob Fodder, Propmasters: www.propmasters.net

Leigh Took, Mattes & Miniatures Ltd: www.mattesandminiatures.com

Construction Manager: Terry Apsey

HoD Plasterer: Ken Barley

HoD Painter: Adrian Start

Stills Photographer: Keith Hamshere

TERRY ACKLAND-SNOW’S FILM AND TV CREDITS

Film

Masters of Venus, Richard the Lionheart, The Pink Panther, The Haunting, In the Cool of the Day, The Yellow Rolls-Royce, Carry on Cleo, A Shot in the Dark, Operation Crossbow, The Liquidator, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Lady ‘L’, Fahrenheit 451, Eye of the Devil, Blue Max, Half a Sixpence, 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Anniversary, Battle of Britain, Hoffman, Mr Forbush and Penguins, Up Pompeii, The Man Who Had Power Over Women, Papillon, Tommy, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, The Return of the Pink Panther, Barry Lyndon, Sky Riders, The Deep, Death on the Nile, Medusa Touch, Arabian Adventure, Nijinsky, Superman II, The Great Muppet Caper, Dark Crystal, Krull, Superman III, Pirates of Penzance, Supergirl, Spies Like Us, King David, Labyrinth, Aliens, The Living Daylights, Consuming Passions, Batman, Rainbow Thief, Doomsday Gun, Get Real, Bourne Identity, Dad’s Army (Original Film), It’s All Happening, The Quest, Puncher’s Private Navy, Rocket to the Moon, Take Me High, Rebel Zone and Papa.

Television

The Avengers, Dangerman, Harry’s Girls, Black Beauty, Shirley’s World, Dick and Julie in Covent Garden, Dopple Clanger, Alternative 3, Inspector Morse Series 2, 3 & 5, Soldier Soldier Series 1–6, Closing Numbers, Kavanagh QC, SOS, Monsignor Renard and Without Motive.

INTRODUCTION

I’ve worked in film art departments since I was a teenager and I can’t tell you how much I’ve enjoyed it. Thinking back to the amazingly talented people I’ve worked with and the countries I’ve worked in, what a very lucky man I am! But how do you condense a career that spans so many films into a readable book? As my job in the art department has always involved a lot of fairly technical and time-consuming work, I thought it best if I sidelined that aspect and just chose a few of the films that I personally found both highly enjoyable and often challenging to work on and which you, the reader, will hopefully recognise from your visits to the cinema – so here goes!

I was the youngest of four brothers: Barry, Brian, my twin Keith (older by 15 minutes) and then me. As a family we weren’t very well off but Mum and Dad did a great job bringing us up despite the struggles. I remember one Christmas Dad found a couple of bicycles that had been dumped and set about restoring them. He painted the frames maroon and the wheels silver. The fact that one was a girls’ bike and one was a boys’ didn’t matter to us at all. We were so thrilled with the present.

As youngsters, Keith and I were always up to a bit of mischief. At that time in and around London there were thick fogs called pea-soupers. These were a problem for cars but not so much for us on our bikes as we knew the local roads in north-west London, particularly Long Lane to the A30, like the back of our hands. As our red rear lights were reasonably visible, we decided it would be a good idea to offer to guide the motorists for the princely sum of 6d per mile. This all went very well until we decided to call it a day as we were getting cold and hungry, so we set off towards home. However, we didn’t think to tell the drivers, so they followed us all the way to our gate. Dad was not best pleased at having to sort it out!

My painting of the ‘factory’, which I did when I was 11.

Dad had worked as a carpenter on such films as The Thief of Baghdad, where he made friends with a fellow carpenter called Les Cleaman. When the film work finished and the construction crew were made redundant, he decided to start Ackland-Snow Limited with my Uncle Percy, turning an old chapel in Stanwell into a factory. It had an old-fashioned petrol pump at the front, which was very handy for the company! They took on Les straight away and among the first things they made were oak doors for the local church, before progressing to small sets for the BBC.

I always loved drawing and painting. In front of the factory was a hardware shop, so when I was 11 years old I did a painting of the shops. You can see the factory chimneys in the background.

Les Cleaman left to take up a permanent job with the BBC and was eventually promoted to head of construction there, which enabled him to give Dad more projects. After early jobs building backing in the car park of the chapel for new presenters such as Richard Dimbleby, Dad was given bigger drama sets to work on, such as Dixon of Dock Green, Quatermass and The Day of the Triffids.

Growing up, my twin brother Keith and I used to do small jobs in the factory, such as pulling nails out of wood ready for re-use. We were later promoted to cutting wooden pins for the carpenters to make what were then ‘gatelegs’, which are folding rostrum legs. For this we were paid 6d an hour – quite a lot for a couple of young lads in those days! We started to work properly in the factory at 16 years old and we were very lucky to have this as a starting point.

Also working at the factory were my other brothers Brian and Barry, the latter of whom sadly died in his 40s of cancer. Brian, four years older than me, was asked to work on a small film at Elstree Studios, with art director Scott McGregor. This was the start of Brian’s long and successful career in film. My chance came when Scott McGregor asked Brian to work on another film with him but, as he was already committed to another project, he recommended me. This was my big chance, at 17 or 18 years old, but I must confess I can’t remember the name of the film! After that Brian went on to bigger productions, such as Becket (1964) with production designer John Bryan and art director Maurice Carter. He eventually won an Oscar for A Room with a View.

The studios known as ‘Elstree’, based in Borehamwood and Elstree in Hertfordshire, have gone through several changes of owner and name over the years since film production began in the area in 1914. At the time it was possibly the largest film and television studio complex outside of the USA and was owned by the Danziger brothers, who specialised in very low-budget features and featurettes, geared primarily to television. You can forgive me for thinking that I’d actually arrived in Hollywood as I walked through the gates for the first time!

From then on I worked on many short films, such as The Tell-tale Heart (1960), with art directors Norman G. Arnold and Peter Russell. I went on to a series for television called Richard the Lionheart (1962), with a new art director called Roy Stannard.

While I was working on Richard the Lionheart I was given a white envelope that, when I opened it, I realised was two weeks’ notice. This notice was part of the ACTT 1 union rules but I thought I’d been given the sack. Being a sensitive soul and ever so young, I cried, as I thought I was the only one who’d been given the push. The camera operator could see how upset I was and told me that everyone on the unit got one and they were known as the Chinese handbill! I was so relieved that I could go home and tell my father that this was the normal procedure. However, he already knew what it meant as he had worked as a carpenter on films like The Thief of Baghdad and had received one or two of these in his career.

About a week after finishing on Richard the Lionheart I went back to Danziger Studios for a visit as I wanted to see what was being filmed. I inadvertently walked into shot wearing a bright yellow anorak – what a dummy! It was a wartime scene with Sherman tanks and a lot of heavy Second World War vehicles. The set was a one-way street so the vehicles had no room to turn around and they all had to be reversed back to the start. Never would I do that again – a huge lesson learned!

I had a call from an art director called Elliot Scott (Scotty) who was working for MGM and asked if I would like to draw for him. I was delighted so started on the Monday morning at Borehamwood. This was my dream come true. I had to clock in at the gatehouse and on my way to Scotty’s office I passed two people going in the opposite direction. They were Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton!

However, not all parts of the job were that exciting. I had to work for the studio maintenance engineer, drawing up electrical plumbing diagrams. Thankfully this job only lasted for a few weeks though and I then went on to work on various television series, such as Dangerman and The Cheaters, as well as many music videos. At last I was working for MGM in the art department in a major studio! I worked there for about three and a half years and I had the good fortune to be mentored by Reg Bream, who was, in my opinion, the best draughtsman at that time. I learned such a lot from him.

Diagram of The Haunting, with me and the prop man leaning against the door.

One film I worked on was In the Cool of the Day (1963), starring Peter Fonda. I was so nervous to be working for art director Ken Adam as he was so very well respected but I was lucky I still had Reg Bream alongside me, as well as art director Peter Murton, looking after the locations in Greece.

I later worked with Elliot Scott on many more films, such as The Yellow Rolls-Royce, starring Rex Harrison, A Shot in the Dark, starring Peter Sellers and Herbert Lom, and The Haunting