1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

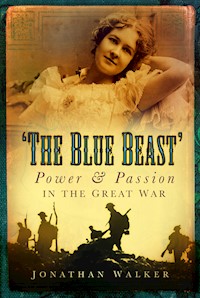

'The Blue Beast'—Edwardian slang for sexual passion—is the true account of the intimate lives of three extraordinary Edwardian women. Drawing on private family archives and highly revealing letters and diaries, the story examines how they became mistresses or confidantes of some of the most powerful men in Britain, men who profoundly affected the Empire's efforts in the First World War. The wealthy and voluptuous American adventuress, Emilie Grigsby, claimed she was the 'mascot of High Command' – and not without good reason. She courted the press baron Lord Northcliffe, the philandering Quartermaster-General, Sir John Cowans and The Times military correspondent, Colonel Charles Repington, all of whom fell under her spell. It was manipulation on an ambitious scale, although eventually her schemes unravelled. Meanwhile, the sensuous and statuesque Winifred 'Wendy' Bennett launched into a passionate affair with the Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Sir John French. 'The 'Blue Beast' uncovers how they conducted their relationship, whilst French wrestled with crisis after crisis to keep command of a vast army on the Western Front. Finally, the strong-willed and aristocratic Hon. Sylvia Henley replaced her sister Venetia Stanley as the close confidante of Prime Minister Asquith. It brought her great influence; but it was no compensation for the personal heartache that followed. Taking the reader on a journey into London's High Society during the glittering Edwardian era and the tumult of the Great War, Jonathan Walker uncovers a story of power, passion and betrayal.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Introduction

PART I Winifred Bennett

1 A Romanian Cradle

2 ‘To Die Would Be an Awfully Big Adventure’

3 Afternoon Delights

4 Elysium

PART II Emilie Grigsby

5 Southern Belle

6 Mascot of High Command

7 Salons and Cabals

8 Reputations

PART III Sylvia Henley

9 A Liberal Heritage

10 ‘One Half of a Pair of Scissors’

11 Betrayal

12 A Changing World

Afterword: ‘The Human Soul on Fire’

Notes

Bibliography

Plate Section

Copyright

Acknowledgements

While the last of the main characters in these pages died in the 1980s, their families can still provide a direct link. It was my good fortune to come into contact with the descendants of two of these extraordinary women. My sincere thanks to sculptress and gardener Camilla Shivarg for her kind hospitality and generous help in allowing me access to the papers and albums of her great-grandmother Winifred ‘Wendy’ Bennett, and for her permission to quote from the papers and reproduce photographic images. Similar thanks to her father, Alexander Shivarg, for unravelling some of the complexities of Winifred’s family connections.

Anthony Pitt-Rivers extended the same kind hospitality and allowed me to examine his amazing collection of Stanley family photograph albums. He gave me valuable insights into the world of his grandmother, the Hon. Sylvia Henley, and I acknowledge his kind permission to reproduce photographs of Sylvia, her family and friends. As the senior member of his family, he kindly granted permission to quote from Sylvia’s correspondence, held in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Anna Mathias was similarly gracious in granting permission for me to quote from the correspondence of her grandmother, Venetia Montagu.

My thanks to Helen Langley, the Curator of Modern Political Papers at the Bodleian Library, Oxford University, for her assistance and my thanks to the Trustees of the Bodleian Library for their permission to quote from letters in the Sylvia Henley collection. I am also grateful to the Bonham Carter Trustees for their permission to quote from the letters written by Herbert Henry Asquith.

I acknowledge the help of Tony Richards and the Department of Documents, at the Imperial War Museum, for their assistance in accessing Lord French’s correspondence and my thanks to the Trustees of the Imperial War Museum for their permission to quote from the letters of Field Marshal Lord French and to reproduce his image from their photographic collection. His impenetrable handwriting is a huge challenge to any researcher, and must have gone some way to allaying fears about the consequences of his letters falling into enemy hands. Deciphering the entire collection was certainly a labour of love for me. We do not know the effect it had on his mistress, but in certain photographs, ‘Wendy’ does look slightly ‘boss-eyed’.

My thanks to the staff of the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives for helping me access records and to the Trustees of the LHCMA for granting me permission to quote from the diary of Lady Hamilton, contained in the papers of her husband, Sir Ian Hamilton. I am grateful to fellow author Celia Lee, for originally drawing my attention to the value of the Hamilton Papers and for providing me with background material on Charles Repington.

The late Professor Richard Holmes, who wrote a colourful and informative study of Field Marshal Lord French, gave me the benefit of his considerable knowledge of the Commander-in-Chief. Richard’s humour and spirit in the face of failing health was an inspiration to all. (The publishers would also like to take this opportunity to express their admiration and gratitude to a great historian and a generous man, always ready with advice and help with Spellmount titles, happy to lend his own authority and reputation won over many years to the work of other authors.) I also appreciate the help and support of fellow researchers and medal experts, Keith Northover and John Arnold, while Professor Donald Thomas, Michael Walker, Chrissie Parrot and Mike Read all helped me to locate sources. Jasper Humphries, Director of External Affairs at the Marjan Centre for the Study of Conflict and Conservation was always a constant reference for historical accuracy. My thanks to my good friends Mark and Geraldine Talbot, Derek and Jo Lamb and Peter and Sue Hansen for their generous hospitality while I was researching.

I have made every effort to obtain the necessary permission to reproduce copyright material in this work, though in some cases it has been impossible to trace the current copyright holders. Any omissions are entirely unintentional and if any are brought to my notice, I will be most happy to include the appropriate acknowledgements in any future re-printing. I acknowledge permission to quote passages from the following: the novelist Francis Wyndham, and his agents Rogers, Coleridge & White for passages from his novel, The Other Garden; Little, Brown Book Group for Dawn Chorus by Joan Wyndham; Oxford University Press for The War in the Air, Vol. III by H.A. Jones; Penguin Group for Sex and the British by Paul Ferris; Constable & Robinson for Thanks for the Memory by Mary Repington; the extract from The Autobiography of Margot Asquith, edited by Mark Bonham Carter, is by kind permission of the Trustees of the Bonham Carter/Asquith Papers held in the Bodleian Library; United Agents Limited for permission to quote from Diana Cooper by Philip Ziegler; Orion Publishing and John Julius Norwich for kind permission to use extracts from his edition of his father’s diaries, The Duff Cooper Diaries; Professor Nicholas Deakin for permission to quote from the correspondence of Henry Havelock Ellis.

While the concept of ‘service’ in most walks of life is fast disappearing, archivists and their assistants manage to maintain a dedication and helpfulness that is so useful to authors and researchers; my thanks to the staff of the Mary Evans Picture Library in Blackheath, London; Elen Wyn Simpson of the Archives and Special Collections, Bangor University; Dr Caroline Corbeau-Parsons of the de Laszlo Archive Trust; Ilaria Della Monica, Director of the Berenson Archive at the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, Florence, and to Annabel Sayers, my very competent researcher in that beautiful city. My mother, Lady Walker, gave me useful advice on the history of fashion, while the antiquarian booksellers, Jarndyce, were most helpful in locating past auction records. My friends at Sidmouth Library, Gill Spence, Meriel Santer, Victoria Luxton and Sylvia Werb, did a marvellous job keeping me supplied with numerous out-of-print titles.

Whilst some of the great houses that feature in these stories no longer exist, there remain a number that are lovingly maintained by their current owners. Special thanks to Quentin Plant for his kind hospitality at his beautiful home; similarly, my thanks to Dr Michael Peagram for sharing his archive at his home, Bletchingdon Park, Oxford, and to Andrew Whittaker for his help and generous hospitality concerning 80 Brook Street in Mayfair.

I wish to express gratitude to Barbara Briggs-Anderson, Curator of the Julian P. Graham Historical Photographic Collection for her help with the portrait of George Gordon Moore. Her work on behalf of Loon Hill Studios in Santa Barbara, helps preserve the legacy of Moore’s post-war creation, The Santa Lucia Preserve in Carmel. The Anders Zorn painting of Emilie Grigsby appears by courtesy of Sotheby’s Picture Library, while Sir John Cowans appears by kind permission of the National Library of Scotland. The National Monuments Register kindly gave permission to reproduce their image of ‘Old Meadows.’ Emilie Grigsby’s couture collection is housed in the Victoria & Albert Museum and the image of her original Poiret mantle is reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Victoria & Albert Museum and the Design and Artists’ Copyright Society. The Library of Congress in Washington is a rich source of photographic material, not only concerning US history, but also Edwardian Britain. Images from the library’s collections from the Bain News Service, Carl van Vechten and the Moffett Studio are reproduced in this book.

Finally, I have appreciated the help and advice of Shaun Barrington of Spellmount and The History Press. As always, I am indebted to my wife Gill, who has endured three years of my immersion in Edwardian England and has supported me all the way along this project. It has been a fascinating journey.

Jonathan Walker, 2012

Introduction

This is the true story of three intriguing Edwardian women who became mistresses or close confidantes of some of the most powerful men in the British Empire. These women reached the zenith of their influence as Britain embarked on the greatest war that the world had ever seen. Yet their names are hardly known today, eclipsed by the dazzling profiles of their lovers and relegated to the ‘footnotes of history’. Winifred Bennett, Emilie Grigsby and Sylvia Henley were three very different characters from diverse backgrounds. Winifred had an exotic upbringing in Romania, Emilie was the essence of a seductive American adventuress, while Sylvia enjoyed the privileged life of an aristocrat. The first two were certainly mistresses while the latter could be described as a ‘very close companion’ to her suitor. They were not the stereotype of the young ‘kept’ mistress, but were women in their thirties, who were financially independent of their admirers – both Winifred and Sylvia were married, while Emilie was hugely wealthy in her own right.

In fact, most Edwardian women discovered that marriage gave them independence for the first time in their lives. Single girls, especially before the war, were subject to extraordinary protection. Their reputation had to be spotless and their lives were constantly monitored and chaperoned. Their one release was marriage, though the success of a marriage was thought to depend more upon mutual love and friendship than upon a woman’s sexual fulfilment. Yet that idea was already under attack by enlightened women, and Winifred Bennett was one who had lost patience with a sterile marriage. Once she had discovered the power of her allure, the temptation to test it became irresistible.1

Many members of London ‘society’ knew about these affairs, but because these women were discreet, they found they were accepted by many society hostesses. Other women might be curious, while most men were captivated by their company. After all, they epitomised the ‘blue beast’ – Edwardian upper class slang for sexual passion – a subject most women would only whisper about in mixed company. Conversation amongst their girlfriends was another matter.2

If sex was still largely a taboo subject for polite conversations on the Home Front, what was happening on the Western Front? The Great War poets concentrated relentlessly on the horror and pity of trench warfare, the vision that overarches every interpretation of the war. But few soldiers at the time spent their days thinking about the ghastliness of the Western Front. Their diaries and letters reveal that when they were not enduring periodic terror, they were exhausted from constant labouring duties, or if in reserve, they were kept busy with repeated training and exercise sessions. When they did relax, they thought about home, or more personal, physical needs. Charles Carrington, author of the hugely successful memoir, A Subaltern’s War, and a soldier who had seen as much action as the poet Siegfried Sassoon, had no truck with Sassoon’s ‘precious and gloomy’ view of the soldier’s lot. ‘What most young soldiers talked and wrote letters about,’ he countered, ‘were girls, football, food and drink.’3 Indeed, it is no surprise that contemporary marching songs confirmed that girls, and the possibility of sex, dominated the thoughts of these young men. As they marched up to the front, singing to the tune of ‘Tipperary,’ the soldiers usually substituted the familiar words we know today, with their own robust lyrics:

That’s the wrong way to tickle Marie,

That’s the wrong way to kiss:

Don’t you know that over here, lad,

They like it better like this.

Hooray pour la France!

Farewell, Angleterre!

We didn’t know the way to tickle Marie,

But now we’ve learnt how.4

They certainly had. The bill for tickling Marie during the war was over 150,000 hospital admissions for venereal disease, in France alone. Some soldiers even visited brothels because they wanted to deliberately catch VD and be invalided out of action. While the ranks would join brothel queues – and according to one participating soldier, they often exceeded 300 men – some officers enjoyed the services of more discreet prostitutes.5

If most soldiers had sex on the brain, the common conception was that their superior officers and the senior politicians running the war were somehow devoid of sexual impulses. There remained a conspiracy of silence about their private lives and if there was any whiff of scandal, it was ignored or denied by a compliant press. The overriding concern was that ‘the lower orders’ should not be exposed to bad behaviour by senior military commanders, or indeed politicians. Consequently, this security from exposure only helped to encourage some leading figures, so that their sex lives exploded out of control and their public life came to grief. There had been sex scandals in the late Victorian period. Everyone in political circles knew about Charles Parnell and his mistress Kitty O’Shea; but when he eventually married her, the saga became public and helped destroy his political career and undermine the Irish Party. Sir Charles Dilke followed a similar path, and following the Cleveland Street brothel raid, Britain’s ‘respectable’ society suddenly began to reassert itself. By 1895, with the trial and conviction of Oscar Wilde, decadence appeared to be back in its box. But after the turn of the century, inspired by the lifestyle of King Edward VII, promiscuity had returned, and as long as affairs were conducted in a discreet manner, society could tolerate it. Such discretion was mandatory, for the ruling class feared that a succession of scandals would pollute the lower classes who, it was believed, would be ill-equipped to handle it. Furthermore, a resulting lack of confidence in the upper class’s destiny to rule could strengthen the hand of the socialists and even threaten revolution.6

For Britain, at least, revolution never came. The First World War brought huge convulsion to Europe and Russia but it was business as usual in Britain’s ‘corridors of power’, and sex was part of the deal. The first wartime Prime Minister, Herbert Henry Asquith, enjoyed a succession of female confidantes and surrounded himself with colleagues such as Lord Curzon, who was only too ready, as the popular ditty went, to ‘sin with Elinor Glyn, on a tiger skin.’ Cabinet Minister Lord Milner dallied with the exotic Cécile, while Lloyd George famously bedded any number of secretaries before meeting Frances Stevenson at the Welsh Chapel near Oxford Circus. He appointed her as both his Personal Secretary and mistress (he eventually married her). Batting for the opposite team, Lord Esher had a penchant for young boys, while the appalling Lewis Harcourt attacked anything on two legs.7

Many senior military figures took mistresses as a matter of course, especially if they were seemingly beyond reproach. Sir John French, as Commander-in-Chief, only answered to the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, who in turn took his orders from the Government (HMG) in the shape of the Secretary of State for War. Sir John Cowens was the Quartermaster-General throughout the war, and along with the Adjutant General, was one of the most senior commanders who sat on the Army Council. Both these men enjoyed a varied sex life outside their marriages. This lifestyle was no less popular in the Navy. Admiral Beatty enjoyed a passionate and lengthy affair with Eugénie Godfrey-Faussett, wife of the aide-de-camp (ADC) to the King. Taking mistresses was also de rigueur amongst allied military commanders. In the early days of the Battle of Verdun, the notable French commander, Philippe Pétain, had to be extracted from the clutches of his mistress, the aptly named Eugénie Hardon, while General ‘Black Jack’ Pershing, the Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Force, found solace in the arms of his exotic French-Romanian mistress, Micheline Resco.8

It is important to remember that power and influence in post-Edwardian Britain still remained within a very small coterie. Politics, the legal profession and the Officer Corps of the Army drew most of their members from ‘society’, a prescribed group who lived in country estates and maintained a foothold within the 20 square miles of central London. The Upper Class formed the bedrock of ‘society’, a class that has been estimated to contain some 60,000 souls at the outbreak of the First World War.9 Society could accept the artistic, the amusing and the clever, as long as they knew the form. Its members could also be tempted by an injection of wealth or beauty, often in the shape of an American heiress. But society remained suspicious of anyone whose family was not recognised, and they felt secure as long as they could exclude the increasingly confident middle classes. Sex, of course, crossed all boundaries and it was a good thing that there were injections of new blood. After all, in such a small social group the gene pool was limited. Nothing illustrates the circumscribed, not to say incestuous nature of these relationships better than the case of Patsy Cornwallis-West. In 1874 she enjoyed a spell as a mistress of the priapic Edward, Prince of Wales, and gave birth later that year to a son, George. When he came of age, George married Lady Randolph Churchill (Jennie), who was 20 years his senior, but who also had been a mistress of the Prince of Wales.

The medium for passion and confidences was, of course, the letter. Postal services were remarkable compared to today. The ‘penny post’ had been in force for decades and the fixed price would only come to an end in 1918. In London, collections took place from pillar boxes every hour up to midnight, and deliveries were made every hour up to 9.00pm at night. So lovers could write a letter to their amour and receive a reply that same day – an impressive system, considering it was 100 years before emails. The onset of war affected the postal service, with large numbers of postmen enlisting in the services, but this shortage was partially alleviated by the enrolment of women. What may surprise the modern reader is the volume of letter writing that went on. Lady Cynthia Asquith, married to Herbert, one of the Prime Minister’s sons, observed that in one typical morning’s post she received, apart from letters from her husband and various girlfriends, letters from male friends ‘Ego, Lawrence, Aubrey and Bluetooth’.10 All were full of joy, sorrow and gossip which would be dutifully answered. Yet there were glaring cases where people did not write. The Prime Minister H.H. Asquith, for example, was a prolific correspondent with all his ‘harem’ but inexplicably never wrote to his son Raymond during Raymond’s ten-month service at the front. It was a mistake that Asquith never had a chance to rectify before his son’s death.

Another enthusiastic man of letters was Field Marshal Sir John French. If the researcher has the patience to decipher French’s appalling handwriting and decode his hidden messages, his letters to his mistress Winifred Bennett are a treasure trove of political and military gossip.11 When the Imperial War Museum purchased this collection of 99 letters at auction in 1975, they did so primarily for the valuable insight they gave into the mind of, and pressures on, the Commander-in-Chief. The letters provide some fascinating insights into his views and opinions of his French allies, as well as his own colleagues.12 Fortunately for this study, they also provide marvellous glimpses into the world of wartime London society as well as illuminating the real passion of French’s relationship with Winifred. This society may have been frivolous, vain and full of excess but its members included some of the most influential and powerful people in the country and as a social group, they deserve to be studied.

Sylvia Henley’s correspondence, particularly her letters to her husband, fulfil much the same promise. They include valuable comments on the political leaders of the day, especially H.H. Asquith, to whom Sylvia was emotionally tied. There is fascinating social comment as well as gossip and it must be remembered that gossip was not just confined to women. The politicians thrived on it and their wives and mistresses acted as conduits for every titbit of military or political news. This proved too much for the more taciturn commanders, such as Haig or Kitchener. The latter, especially, blamed his own reticence on his Cabinet colleagues, whom he maintained could keep nothing from their women – except for Asquith, who told other people’s wives. ‘If they will only divorce their wives,’ Kitchener growled, ‘I will tell them everything.’13

Considering their world was so small – geographically and socially – it is surprising that Winifred, Emilie and Sylvia rarely met. They certainly knew of each other’s existence from society gossip. When Emilie visited an art exhibition, she was struck by the beautiful portrait of ‘Mrs Bennett’, whose dark, penetrating eyes mesmerised the room. And when Sylvia was holidaying in Homburg with her sister before the war, she spied the renowned beauty ‘Mrs Bennett’ across the town square. Sylvia even photographed Winifred in her white dress and parasol, as you might snap a celebrity, and when she returned home, pasted the image in her personal photo album.14 Beauty and mystery were appreciated in this age, as in any other.

The Edwardian period, followed by the tumult of the First World War, brought huge change to women’s lives, but the extent of that change depended on class, age, and martial status. Nevertheless, Winifred, Emilie and Sylvia were all extraordinary women who carved out their own destinies as mistresses or confidantes. They would never again enjoy such influence or indeed, have so much excitement. But it was always a dangerous game.

PART I

WINIFRED BENNETT

1

A Romanian Cradle

Winifred Bennett always had the air of an exotic English beauty. She was tall, slim and elegant, but her demeanour and her heart belonged to another, more untamed and Latin culture. Although she was of British extraction, Romania owned her soul.

Her family, the Youells, originated in East Anglia, where they had been established for generations around the town of Southdown on the Norfolk/Suffolk borders. Winifred’s grandfather was a Great Yarmouth banker and her father Edward became a shipping agent. But Edward Youell had his eyes set on wider horizons. He married Mary Watson, whose family had business interests in Romania – a country largely unknown in Victorian Britain. Nevertheless, the couple emigrated in 1874 and Edward joined the family shipping agency, Watson’s, based in the Romanian port of Galatz. He swiftly prospered, becoming a partner in the new business of Watson & Youell. With a successful enterprise behind them, Edward and Mary produced three girls. Winifred, the eldest, was born in 1875, Sybil in 1879 and Gladys followed in 1882.

Winifred’s granddaughter, Joan Wyndham, recalled her grandmother’s exotic upbringing in Romania ‘in a family that still greeted incoming guests with bread, salt and a five-gun salute’. According to Joan, Winifred ‘had been cared for by a gypsy wet-nurse and had a tame bear that walked up and down on her back if she was ill’.15 Such superstitious practices were widely followed in Romania amongst all social classes and the ‘bear treatment’ was a staple cure for all sorts of maladies. In the event of an illness, a gipsy would be summoned, arriving with a small bear on a leash with a ring through its nose. The patients lay on their front and the bear climbed on their back and danced up and down while the gypsy thumped a tambourine. At least Winifred never resorted to calling in the local baba, or woman witch-doctor, relied upon by so many rural Romanians.

Romania also had its sophisticated side. The Youell’s home town of Galatz was the largest port on the Danube and a gateway to the vast Black Sea, some 80 miles to the east.16 It had its own vibrant expatriate community and had connections to Britain – General Gordon, the hero of Khartoum was a past inhabitant. The town’s social life was dictated by its climate. Winters in Galatz were harsh and when the snow arrived, it was driven in across the plains by the bitter easterly wind, or viscol. Still, urban life was more hospitable than the freezing countryside where entertaining ceased between November and February. As winter gave way to spring, so social activities picked up in the town, and by summer, the hectic round of balls, receptions and parties got under way. In Galatz, one of the social rituals during the summer was the evening promenading that took place around the Strada Domneascâ and Public Gardens. With the heady scent of acacias and lime trees in bloom, pedestrians enjoyed the balmy evening air and would be joined by a succession of ‘victoria’ carriages, pulled by sleek, beautifully groomed horses, driven by grooms in full livery. Like most of the town’s wealthy elite, Edward Youell hired both his carriage and the Russian coachmen by the month, enabling Winifred and her sisters to take full advantage of this piece of theatre. They draped themselves across the carriage seats, parasols in hand, to be admired by a procession of young men. Always clothed in the latest Paris fashions, the girls would smile and nod at the passing young army officers, strutting about in tight scarlet tunics.17

One hundred and fifty miles away lay the capital, Bucharest, which offered more interesting social opportunities for the girls, and there was a lively young court surrounding the Romanian royal family. Romania was a comparatively new country, formed in 1861 from the Principalities of Walachia and Moldavia, and from the beginning the new state was always subject to the whims of the neighbouring empires of Russia, Austria and Turkey. Choosing a monarch for the new state was not easy. There was too much in-fighting for a Romanian to be selected for the throne, and the first local candidate was ousted within a few years. He was replaced by the unimaginative but dutiful Prince Carol, a scion of the Prussian royal family. While he successfully managed the basics of the state apparatus, Carol walked a tightrope in the handling of foreign affairs. Because of his family connections he was pro-Prussian, while his people were decidedly pro-French – a position that was sorely tested during the Franco-Prussian War in 1870.18 At last, in 1881, Romania was elevated to the rank of a Kingdom and Prince Carol was proclaimed King Carol I.

Carol’s marriage to his wife Elizabeth was not a happy one, and their hopes for the future lay in their son, Prince Ferdinand. In 1893 the timid Prince married eighteen-year-old Princess Marie of Edinburgh, granddaughter of Queen Victoria and a niece of the Russian Tsar. Princess Marie’s mother was very concerned, not so much about the marital match, but more about the state of the country her daughter had adopted. ‘Very insecure,’ she warned, ‘and the immorality of the society in Bucharest quite awful.’ And that sharp observer of court life, Lady Geraldine Somerset, was similarly unimpressed. ‘Disgusted to see the announcement’ she groaned, ‘of the marriage of poor pretty nice P. Marie of Edinburgh to the P. of Roumania! It does seem too cruel a shame to cart that nice pretty girl off to semi-barbaric Roumania. ‘The early days of their marriage were not promising. Ferdinand was attentive enough but his awkward physical advances failed to register with his home-sick bride, who yearned for more passion and a mature romance. Furthermore, her new home was hardly welcoming. The Palatul Victorei was a solid, sombre place with heavy furniture, no flowers and few comforts. However, the Princess soon found support and friendship from amongst the English members of Romanian society – particularly Winifred and her gregarious sisters.19

Barely four years into her marriage, Princess Marie, or ‘Missy’ as she was known, began an affair with her ADC, Lieutenant Zizi Cantacuzèe. While her husband was ill, Marie spent long hours in the saddle with her riding partner Zizi, and even an enforced separation in Nice and Villefranche failed to cool the Princess’s obsession. She returned to find that Zizi had been ‘moved sideways’ but to her delight, was now leaping about the royal court as a ‘gymnastics instructor’ to the King. Marie was producing babies at an alarming rate, which pleased her in-laws, but her public displays of affection with her athletic lover were dynamite to the Romanian Royal Family. However, while her family disapproved, Romanian society indulged her extra-marital activities and even applauded her affairs, which included a later friendship with the hugely wealthy Waldorf Astor, as well as a passionate affair with the Romanian aristocrat, Prince Barbo Stirby. Hearing of her tangled and arguably neurotic love life, the British Royal Family were relieved that her earlier possible match with Prince George (later George V) never materialised. Meanwhile, not to be left out, Crown Prince Ferdinand embarked on a number of extra-marital relationships, but was careful to be more discreet.

Princess Marie’s affairs were closely dissected by the Romanian court and the expatriate community. Indeed, the three Youell sisters were avid admirers of the errant Princess, who had evolved into a style icon – her newly decorated boudoir and Byzantine tastes were quickly adopted by those in her social circle. Winifred and her sisters were soon sporting this exotic fashion; with their dark eyes and their command of French and Greek, they were soon assimilated into smart society.20 Another close friend of the girls was Héléne Chrissoveloni, the beautiful daughter of an extremely wealthy Greek banker.21 Parties at the Chrissoveloni villa in Galatz were glamorous and boisterous affairs, hosted by Héléne’s brothers Zanni and Dimitriu with the Youell sisters as regular guests. During these evenings, mellow music and dances soon gave way to fast, traditional Romanian dances such as the Galaonul De La Birca, fuelled by copious quantities of tzwica plum brandy. Dancing was, after all, something akin to a national pastime in Romania and it was not surprising that romantic liaisons flourished in this atmosphere. Sybil Youell became close to Zanni Chrissoveloni, while the statuesque Winifred dallied with Prince Ghika and other young blades. Winifred found these young army officers very seductive. With their Romanian swagger and flashes of wit and anger, these men could drink heavily and display violence towards their women, yet maintain an extraordinary hold over them. Winifred’s friend, Ethel Pantazzi observed the species in its natural habitat:

The men stand in the middle of the ballroom deciding on their future partners. The masculine attire deserves as much notice as that of the fair sex. For one blackcoated civilian there are ten officers. Most of the military contingent glitter with gold braid and medals. Some uniforms are red, some brown, some black, the collars and sleeves slashed with yellow, pale blue or pink; all are fashioned to show a slender waist to the best advantage. Patent-leather boots, moulded to fit foot and ankle without a wrinkle; perfectly cut white gloves, every shining perfumed hair in place, an occasional monocle fixed immovably to the eye – this is the ensemble presented before the music strikes up. Then each rapidly approaches the lady of his choice, smartly clicks the heels together and bows.22

In this testosterone-fuelled atmosphere, Winifred’s suitors were romantic but totally faithless and in the end she settled for less exotic fare in the shape of a British diplomat. Percy Bennett was an ambitious mandarin who had recently arrived at the British Consulate in Galatz, one of sixteen international consulates that had sprung up around the city’s thriving grain and timber trade. He was also attached to the European Commission of the Danube, an international body briefed to control and develop trade along the great river. This organisation had a large entertaining budget, which provided lavish parties at its headquarters in a palace in Galatz, or on board its boat, the Carolus Primus. And it was on board this pretty steam yacht that Winifred first encountered Percy. In 1896, after a short romance, Percy proposed to her, and in the Romanian tradition, offered her diamond earrings rather than a conventional engagement ring. Some months later, the couple married, but it was hardly a grande affaire and friends thought the match was surprising. Winfred was taller than her spouse, more vivacious and outgoing and at 21, was ten years younger than her rather solid and humourless husband. That was a problem, but one that Winfred was prepared to overlook, since Percy had ambition and looked set for a successful career that could take the couple all over the world. It was evident from an early stage that Percy was single minded.

Born in 1866, Andrew Percy Bennett was raised in the quiet town of St Leonard’s, in Sussex. His father, the Reverend Augustus Bennett had hoped that a career in the church might suit the young Percy but instead the boy finished Cambridge and chose to head straight into the diplomatic service. In 1890 he was posted to Government House in Hong Kong, a territory only ceded to Britain less than 50 years before, but one that had nonetheless become a flourishing commercial centre, bursting with energetic traders and entrepreneurs. The island was already overcrowded, having risen from a population of 4000 in 1841 to a quarter of a million souls when Percy arrived. In addition there was a boat population of 32,000 immigrants, who helped drive the thriving economy. Hong Kong enjoyed a free port status and there were no customs duties on its imports of rice, flour, opium and tea. But there remained an ever-present threat to its trade – piracy. Instances of this capital crime had fallen with the rise of the faster steamships, but a notorious band still operated in the region, who attacked and looted a passenger ship, Namoa, in December 1890. This sort of incident was disastrous for Hong Kong trade and Percy was determined to see justice carried out. The pirates were captured by the Chinese, swiftly tried and then executed the following year by traditional but brutal Chinese means. As a trade official, Percy was on hand to witness this ghastly spectacle on Kowloon beach when 34 prisoners in two batches were beheaded in front of a crowd of Chinese and European spectators, some of whom posed afterwards for photographers besides the decapitated pirates.23 Such grim displays did not put Percy off his job and he continued to impress his superiors with his crisp and business-like demeanour, which resulted in his promotion to Vice-Consul in 1893. He was briefly posted to Manila, before returning to Galatz the following year.24

The Bennetts did not have long to wait before yet another new posting was offered to Percy – this time in New York. As HM Consul, he and his new glamorous wife arrived there on board SS Campania at the end of 1896 and he remained there for three years, while Winifred travelled backwards and forwards to visit her family in Romania. Winifred became pregnant and in 1900, the couple returned to Europe, with Percy’s new appointment as commercial attaché to the British Embassy in Rome. On 26 April 1900, Winifred gave birth to their only daughter, Iris. She was not confined for long and soon entered into Rome’s hectic social life.

The Edwardians and post-Edwardians loved to dress up and they lived in an age when there was an abundance of rich, well-made fabrics and talented seamstresses who could create glorious costumes for all occasions. They also adored the stage and one way of combining both passions was to perform in Tableaux Vivants (living pictures). Winifred was an enthusiastic player and lost no time in appearing before the King and Queen of Italy in a series of these tableaux. The theatrical performances had originated in Italy and the craze spread to the rest of Europe. They involved the cast dressing up in period costume and arranging themselves in a rigid pose to recreate a classical tale or painting. The curtain would be pulled back and the audience would gasp and then applaud as they surveyed the exotic and colourful scene. No-one in the cast moved, which was quite an achievement, given that the scene might be ‘Diana the Huntress’ involving diaphanous costumes in a draughty theatre or country house drawing room.

Winifred’s statuesque beauty was not just confined to the stage; she stood out on the diplomatic circuit and her presence at social or embassy events was often noted in the European newspaper columns. Percy’s subsequent appointment as Commercial Secretary and Principal Attaché at the British Embassy in Vienna provided further opportunities for Winifred to shine on the society circuit. She took great delight in helping to arrange the marriage of her younger sister, Gladys, to Captain Alexander Hood, in a splendid Viennese ceremony. Winifred was still a much photographed beauty and in a pre-celebrity age, professional or amateur photographers would relish the chance to capture her image. She also had her portrait painted by the celebrated artist Philip de László, who was working out of his studio in Vienna. According to his friend, Otto von Schleinitz, de László’s portrait of Winifred ‘created a happy combination of classical and modern elements’. Whatever the merits of its execution, the portrait found favour with the sitter and when de László moved to London after 1907, she lent it to him for his exhibitions in the capital.25

The striking ‘Mrs Bennett’ could be glimpsed at all the right parties or balls and whenever the British Monarch, Edward VII, visited his favourite spa resort of Marienbad in Bohemia, Winifred would leave Vienna and join the throng following the royal visitor. In fact the King visited the spa town’s Hotel Weimer virtually every year, to take the waters and vainly attempt to diet. After nine years of this treatment he was still universally known as ‘Tum Tum’. However, he did try some gentle exercise and could play a respectable round at the Marienbad Golf Club, where Percy happened to be secretary. Introductions to the royal personage abounded and Percy and Winifred found they were often in illustrious company.

In 1905, just as Percy was growing accustomed to the grand life, he was moved off the central European stage and back to Romania. Winifred was delighted because she could catch up with family and friends, but Percy’s new brief was very pedestrian. He was to promote Britain’s trade interests at the impending Bucharest International Exhibition. It was to be held in a newly designed park in the centre of the capital. With its own lake and landscaped gardens, the event was supposed to showcase Romania’s emerging commercial interests. But as planning got under way, Percy was distracted by another, more dramatic international event.

On 2 July 1905 the Russian battleship Potemkin suddenly appeared without warning, just off the main Romanian sea port of Constança. The crew had mutinied in the Black Sea, killing seven officers, and then called at Odessa to incite revolution. Finally, Potemkin steamed down the west side of the Sea towards Constança with the Russian navy in pursuit. Percy, who was a keen photographer, happened to be in the port at the time and rushed down to the main harbour to snap the vessel offshore. For the moment that was as close as he got, for the Romanian authorities refused to re-supply the ship and fearful that their pursuers would catch up with them, the mutineers sailed away. They then tried to access the Russian port of Theodosia, but failed and so returned to Constança on 8 July, flying the Romanian flag. The mutineers entered negotiations with the Romanian authorities, in the hope that asylum might be granted, and the crew surrendered the Potemkin, half-scuttling her in the process. As the sullen mutineers entered the town, they were surprised to receive a rapturous welcome from many of the local Romanians. Amongst the crowd that thronged the quay was Percy Bennett, who joined in the lively but stilted discussions with some of the mutineers, one of whom cut off his sailor’s ‘Potemkin’ hat band and gave it to the diplomat.26 Some of those who gave themselves up to Russian representatives in the town were subsequently executed but hundreds of other mutineers managed to escape into Romania’s interior.27

As the excitement of revolutionary events died away, Percy had to return to the more mundane business of Bucharest’s International Exhibition. When it finally opened, it was a disaster from the very beginning. King Carol’s overlong opening address was delivered in his monotonous German accent, which few could understand and the unbearable heat caused many of the frock-coated delegates to collapse. Interest was only revived when one of the organisers brought forward a parade of Roman soldiers in full armour and scarlet cloaks to wander through the exhausted crowd.28 For all its pretensions to European modernity, Romania was still a backward country. There were no railways and few good roads, and although the capital, Bucharest, had acquired some solid European architecture and smart central avenues, many of its side streets were muddy and shabby. Serfdom had only been abolished in 1848 and the largely peasant population had yet to benefit from any government oil revenues. The country did possess a wealthy landowning class known as boyars, as well as a small and increasingly influential middle class of merchants and professionals. Short and dark, unlike their Slav neighbours, they spoke French and saw themselves as a ‘Latin island in a sea of Slavdom’. Their reputation as lovers owed something to their Roman origins.

For those who could afford to escape the stifling heat of the summer in Bucharest, the delights of nearby Sinaia awaited. This was a pretty resort with its own Casino, high up in the Carpathian Mountains where Winifred and Percy were often invited to stay in some of the luxurious villas that dotted the mountainside. It was here that Winifred witnessed at first hand the liberal attitudes of the society. Many male Romanian aristocrats, married or not, considered it was constant open season for romantic conquests. Single Romanian girls though, were under far tighter control than their European counterparts, for not only did they share the restrictions of constant chaperoning but were also often confined to their homes. However, the fortunes of Romanian women often changed dramatically on marriage. Then, freedom was extensive and the taking of lovers was indulged. Even divorce was far easier than in any other European country. For despite being a devoutly religious country, the Romanian Orthodox Church allowed a person to marry and divorce up to three times – each time in church – without any apparent loss of social standing. When a large number of extra-marital lovers were added to the mix, members of the small Romanian high society had a very intimate knowledge of one another.29

The comfortably off seemed immune to mounting grievances amongst the wider Romanian population and in 1907 the country erupted. Ironically, it was in Winifred’s home town of Galatz that the upheaval was most dramatic. The peasants revolted over the failure of land reform and attacked government buildings. The weak government collapsed, and an intimidated King Carol stepped in, using the army to brutally crush the uprising. It was also the very year that Winifred’s younger sister, Sybil married her long-time lover Zanni Chrissoveloni in Galatz, and despite the bridegroom’s enormous wealth, the celebrations were decidedly low-key. The mood had changed in the country, especially since Romanian soldiers had killed thousands of protestors and razed whole villages in the countryside. Any sense of national unity would not return until the country was threatened by the Central Powers in the First World War.

As unrest swept Romania, Percy was moved back to Western Europe and appointed a Royal Commissioner, with the brief to support a series of international exhibitions held in London, Brussels, Rome and Turin. The first show, in 1908 in West London, also celebrated the recent 1904 Entente Cordiale between Britain and France.30 This brought the Bennetts into more civilised territory, yet although Winifred originally saw Percy’s career as rather glamorous, after a while the endless new postings and repetitive round of embassy and consulate parties started to pall. He was wedded to his career and was totally oblivious to Winifred’s desire for attention and for her sexual needs. He took himself extremely seriously and engaged a number of photographers to capture, for posterity, the image of the austere diplomat. Instead of taking him seriously, Winifred began to see her husband as a figure of fun and was much amused by his nickname on the diplomatic circuit, of ‘Pompous Percy’.31 Still, for all his tedious habits, Percy’s latest appointments meant that Winifred was in easy reach of London and Paris; and to facilitate her regular jaunts to the cities, in 1910 Percy purchased a base in London. Number 5 Devonshire Terrace was a three-storey house in a quiet street between the expanding Paddington Station and Kensington Gardens. It would prove an ideal base for Winifred, not only for shopping and meeting friends, but also for pleasures of a more sensual kind.

Winifred had already seen that the diplomatic world was full of irregular relationships and London was no exception. She befriended Henriette Niven, the wife of a landowner and mistress of diplomat Thomas Comyn-Platt. Henriette, or ‘Etta’, was a flamboyant personality and had little interest in covering up her relationship with Comyn-Platt, who was later reported to have fathered her son, the actor David Niven.32 Winifred had been brought up in a sexually liberated world in Romania and although she had enjoyed dalliances, she was about to enjoy her first true passion. By 1910, her marriage to Percy was moribund and, like an increasing number of Edwardian women, she did not feel bound by society’s expectations. Typical of these tenets was the idea that women should not enjoy sex. ‘A modest woman seldom desires any sexual gratification for herself,’ one eminent doctor wrote. ‘She submits to her husband, but only to please him; and, but for the desire of maternity, would far rather be relieved from his attention.’ This was definitely not her creed, for she had done with pleasing Percy and at 35, time was running out for her.33

She soon found pleasure in Captain Jack Annesley. They first met at an embassy party, while the old Etonian was on leave from his regiment, stationed in India. Winifred was immediately struck by his charm, gentle humour and perfect manners. He was five years younger than her. He was sporty, had an illustrious military record and was interested in Winifred from their first meeting – in short, he was everything that Percy was not.34 For one thing, cavalry officers still enjoyed the greatest social cachet and Jack’s regiment, the 10th (Prince of Wales’s Own Royal) Hussars, or ‘The Shiny Tenth’ as it was known, was considered the smartest of the cavalry regiments.35 Indeed, they were the first cavalry unit to be converted to Hussars, years before Waterloo, and counted that great battle, as well as Sevastopol and Afghanistan, amongst their honours. Such a fine regiment required its officers to be well turned out and well equipped, and Captain Annesley would be expected to provide not only his own uniforms and kit but also three horses, one of which had to be a cavalry charger.36 Everything had to be from a prescribed source. His sporting tailors had to be Studd & Millington in Conduit Street, and his shirt makers were to be found in Savile Row. His hatter would be Lincoln Bennett in Sackville Street and Kammon & Co. in New Bond Street would supply his boots. There was no doubt that in his parade dress uniform of plumed busby, blue tunic and breeches, knee boots and jack spurs, coupled with a flash of arrogance, he looked every inch the dashing cavalryman.

Jack Annesley was also very eligible. He was the eldest son and heir of the 11th Viscount Valentia, lately MP for Oxford, Master of the Bicester Hunt and the owner of several fine estates. It was true that the family title was an Irish creation and there was therefore no seat in the House of Lords, but the Annesley family were a collateral branch of the Earls of Annesley and maintained their substantial seat at Bletchingdon Park, north of Oxford. They also held other estates in Norfolk, Northamptonshire and Ireland.37 But it was to Bletchingdon that Jack and Winifred retreated. Since Percy Bennett was constantly away on consulate business, Winifred and Jack’s affair flourished and this beautiful 60-room Georgian house, set in its own 3000 acres of grounds, was the setting for many weekend trysts. There were known as Saturday-to-Monday house parties, which often included Jack’s brother Caryl, or any of his six sisters, while for shorter spells together, the lovers would visit the Annesley’s London house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, or Winifred’s own new house in Devonshire Terrace.38

Jack had previously enjoyed a numerous succession of ‘sweethearts’ and showed little inclination to manage a steady relationship. No doubt Lord Annesley thought that Winifred was at least a stabilising influence on his heir, and there is no doubt that Winifred and Jack were deeply in love. Their relationship may well have been an open secret, but Winifred was certainly not ostracised for it. An illicit affair was perfectly acceptable in some quarters, as long as the lovers were discreet and did not flaunt their activities.39 It also relied on taciturn servants – who recognised all the signs of an affair – as well as the couple’s observance of the strict etiquette for calling on each other. In London, men would normally attend their clubs after four o’clock in the afternoon, always being careful never to arrive home before seven in the evening. This period was then reserved for calling and was often the convenient time for wives to receive their lovers. Visiting cards were a necessary part of the ritual. Women visitors were required to leave two of their husband’s cards and one of their own, or combinations depending on who was in and who was out. It was a complicated and dated etiquette but, as Lawrence Jones recalled, it would remain mandatory during the Edwardian period and for some years after:

For every dinner eaten, a visit must be paid to your dinner-hostess. In the season when dinner-parties before dances were frequent, several Sunday afternoons had to be given up to these visits. If you were lucky and your hostess was not at home you left two small cards, with the corners turned up to indicate that they had been ‘dropped’ by yourself and not by a servant. If your hostess was at home, you must carry your silk hat, stick and gloves upstairs into the drawing-room, as a sign that your visit would not be unduly drawn out.40

Unlike women, men would have their address on their cards and while etiquette had relaxed in the last decade, it was still not permissible for women to call on a man alone. She would have to take a female friend or chaperone. Even as the Edwardian era was coming to a close, the rules of chaperonage were still strict and a single woman had to be escorted home from parties by a married woman, while hotels, with the exception of the Ritz, were definitely out of bounds. Yet, despite these rigid codes of etiquette, there were places where lovers could mingle, out of the public gaze and even without chaperones. In the immediate years before 1914, ‘night clubs’ were expanding and competing with each other to become the most fashionable venue. Ragtime had come over from America and Negro bands were ‘simply to die for’. Night-clubs were opening up everywhere and the tango and fox-trot were even increasingly popular at more formal evenings.41

Night-clubs were simply not Percy’s ‘thing’ and Winifred’s increasing disappearances in the evening at last raised an eyebrow from her husband. There was a furious row when Percy extracted the truth from Winifred. She pleaded with him to keep her lover and he threatened to throw her out. Their nanny had secured young Iris away at the top of the house, but the shouting must have been heard by most of Devonshire Terrace. The situation only quietened down when Winifred told the puce-faced Percy that her lover was shortly returning with his regiment to India and the affair would probably not survive.

So Jack ‘Pick ‘ Annesley, the celebrated ‘beau sabreur’, left London in 1911 and resumed his life in Rawalpindi. During the later years of his regiment’s tenyear posting to India, he had fulfilled the roll of regimental Adjutant, a job only interrupted by his constant round of polo chukkas. This time, together with teammates ‘Gibblet’ Fielden, Billie Palmes and ‘Pedlar’ Palmer, he won the much coveted Inter-Regimental Polo Cup. He was also on parade for the Delhi Durbar in the same year, when George V was crowned Emperor of India. However, this life of ceremonial and sport ended in November 1912.42 While ‘The Tenth’ were deployed to South Africa, Jack was appointed Aide-de-Camp (ADC) to Major-General Hon. Julian Byng, a senior officer of the 10th Hussars. Winifred was delighted, since Jack would be returning to England. Percy sulked.

Jack, as an ADC, would spend occasional weekends at Major-General Byng’s country house, Newton Hall, which was situated on the Easton Estate at Great Dunmow, in Essex. The interesting thing about this house was that it was leased from the legendary Daisy Brooke, Countess of Warwick, ex-mistress of the late King Edward VII. Not known for her discretion – she was called ‘The Babbling Brooke’ – she was still in circulation, though rather desperate to keep the flame alive. She had also recently become an unlikely convert to socialism and the estate had become home to fellow Fabians such as H.G. Wells. This was not quite the company the Byngs normally kept, but Lady Byng was more concerned with keeping the ‘blue beast’ at bay:

Our landlady was the famous and beautiful Lady Warwick, by then grown quite stout though her features remained lovely and her desire to charm every man was as strong as ever … I laughed, having watched the performance as she placed herself with one hand on the top of a wicket gate, her beautiful head thrown back at its best angle; she gazed into Julian’s eyes, and thought she had him fascinated. Such a waste of time, for when I told him, he laughed and said he couldn’t tolerate ‘well-fed ewes who aped skittish lambs’.43

Jack was similarly unimpressed and managed to steal occasional meetings with the more alluring Winifred. But his time in England was limited. For where Byng went, Jack, as ADC, was sure to follow, and promotion soon took Byng to Egypt, as GOC, British Force in Egypt.44 The British presence in Egypt was rather bizarre. The country was, in theory, still part of the Turkish Empire, though Britain had been her ‘protector’ for the last 50 years. No formal written agreements confirmed Britain’s occupation but the Egyptian Army was British-trained and a large number of British civil servants held together the country’s administration. After trade, the prime asset to be protected was the Suez Canal, and this role absorbed most of the 5000-strong British garrison.

When Byng and his entourage arrived in Cairo, they had no accommodation and Jack Annesley found himself billeted along with his Commanding Officer in Lord Kitchener’s house (curiously the German Legation abutted the house). Everyone in the house handled ‘K’ with great delicacy, treading carefully lest the slightest breach in the established order resulted in a blast from the formidable Consul-General of Egypt. The only living thing that avoided his wrath was his pet dove, upon which he lavished inordinate attention, while his sole recreation seemed to be growing orchids. The only woman in the house, Lady Byng, remembered ‘a strange and certainly not a lovable man, an odd mixture of greatness and petty meanness’.45 Consequently, whenever they could, the occupants of the house made off for visits to some of the city museums, which contained treasures from the Valley of the Kings. The city’s skyline was then dominated by Saladin’s great mosque, which topped Citadel Hill. Beyond lay the Sphinx, its paws still buried in the sand, in front of the Pyramids. Dhows plied the Nile while endless caravans of camels trudged along the high canal banks and shepherd boys herded flocks of sheep or goats around the narrow streets. It was a picturesque, though poverty-stricken landscape.

As well as his regimental duties, Jack Annesly, as an ADC was also required to attend the endless round of Cairo dinners and receptions. Byng’s wife Evelyn, being a fluent French speaker, became Kitchener’s unofficial hostess, as well as the leader of Cairo society.46 They hosted visits from numerous cosmopolitan businessmen and Suez Canal magnates, but arranging banquets was always a problem. There were never enough eligible single women to partner the numerous staff officers or legation officials. For while single daughters from local British families could be wheeled out, it was unacceptable for the daughters of well-to-do Muslim families to make up numbers. There was often severe retribution for western-educated Egyptian girls who abandoned the veil and mixed too enthusiastically with British bachelors.

While Jack was engaged in duties in Egypt, Winifred kept up the round of social engagements in London, partnering the reluctant Percy to official and private dinners. He had recently been appointed a CMG, known in the Civil Service as a ‘Call Me God’ – highly appropriate in Percy’s case – and it had made him even more unbearable47 In January 1914, the couple accepted an invitation for dinner from their near neighbour, a Canadian-born entrepreneur and adventurer, George Gordon Moore. An intriguing and mysterious figure, prominent in both London and international circles, Moore had recently acquired the lease of 94 Lancaster Gate. It was a vast and imposing building forming the terrace end of one rank of colonnaded houses overlooking Kensington Gardens.48 George Gordon Moore (not to be confused with the Irish poet and philanderer, George Moore) had taken the house in part to provide a base for his good friend Field Marshal Sir John French. Moore, who had left a wife and child at home in Detroit, was used to entertaining on a lavish scale, but was seen by many as an arriviste. Born in Ontario, Canada, in 1876, he moved to Michigan where he enjoyed a short career as a barrister before embarking on a hugely successful business career as a company promoter. He developed the Michigan electric transportation system as well as controlling public utilities across the US, Canada, Brazil and some German states.49 He was able to retire in 1912 but his connections with German businessmen would later come to haunt him and damage his reputation as a patriot and supporter of Britain.

For the moment though, Moore was fêted in London for his extravagant and legendary parties. One dinner he gave at the Ritz in 1912 boasted flowers that cost £2000, gold jewellery for all the women guests, and a troupe of Negro singers. He made huge efforts to court Asquith as well as his wife, Margot and son, Raymond. Other regular recipients of his hospitality were General Sir John French, Lord Elcho, Lady Cunard and the constant object of his affections, Lady Diana Manners. The generosity was not all one-way. On 13 July 1912, Asquith hosted a large family dinner party and one of the few outsiders invited was George Gordon Moore. He made sure to maintain his currency as an influential figure who ‘knew the right people’ in New York as well as London, and this necessitated frequent transatlantic trips aboard SS Mauritania.50 In 1912 he was also engaged in setting up a game reserve in the Smokey Mountains, on the borders of Tennessee and North Carolina, where he introduced elk, buffalo, bear and the Russian Blue Boar into the rugged landscape. He clearly relished the role of ‘frontiersman’: ‘The biggest boar we ever killed was 9 [feet] from tip to tip. The skin on his neck was three inches thick; eleven bullets were found, which over the years had been embedded in the fat.’51