Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Born between 1885 and 1891, George Patton, Bernard Montgomery and Erwin Rommel all participated in the First World War and, like millions of others, were so affected by their wartime experiences that it became a fundamental influence on their lives. Yet none of the men were dissuaded by the carnage from seeking military careers when the guns finally fell silent. Each became wholly dedicated to the profession of arms and, being exceptional officers and leaders, they prospered. Despite the broad similarities between them, there were some marked differences in their approach to leadership due to the individuality bestowed on them from their genes, upbringing, life experience and relationships. Triumph reveals how these stimuli created three unique personalities which, in turn, each man came to draw from when they became among the most prominent officers in their armies. Exploring the many and various influences that shaped these three officers as men, as soldiers and, principally, as leaders, Lloyd Clark tracks their progress - through war and peace - all the way up to their final confrontation on the battlefields of the Second World War.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 741

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

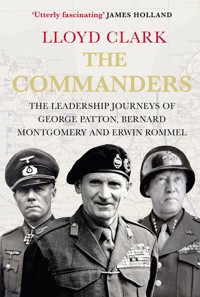

THE COMMANDERS

By the same author

Blitzkrieg:

Myth, Reality and Hitler’s Lightning War – France, 1940

Kursk:

The Greatest Battle

Arnhem:

Jumping the Rhine 1944 and 1945

Anzio:

The Friction of War

THE COMMANDERS

The Leadership Journeys of George Patton,Bernard Montgomery and Erwin Rommel

LLOYD CLARK

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2022 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Lloyd Clark, 2022

The moral right of Lloyd Clark to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The author would like to thank Haus Publishing for permission to quote from Ralf Georg Reuth’s Rommel: The End of a Legend and Pen & Sword for the quotes from Bernard Montgomery’s The Memoirs of Montgomery of Alamein; material quoted from Patton by Carlo D’Este, copyright © 1995 by Carlo D’Este, is used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers. While every effort has been made to contact copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, the author would be pleased to rectify any omissions in subsequent editions should they be drawn to his attention.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-0-85789-728-2

E-book ISBN: 978-0-85789-731-2

Layout and typesetting benstudios.co.uk

Map artwork by Keith Chaffer

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Catriona, with much love.Now and forever.

Contents

List of Maps

Introduction

CHAPTER 1: Early Years and Junior Leaders, 1880s–1914

CHAPTER 2: First Combat, 1914–16

CHAPTER 3: Hard-Won Experience, 1917–18

CHAPTER 4: New Challenges – Leading in Peace, 1919–31

CHAPTER 5: Taking Command, 1932–39

CHAPTER 6: A New War, 1940–41

CHAPTER 7: Three in North Africa, 1942–43

CHAPTER 8: Three in North-West Europe, 1944–45

CHAPTER 9: George S. Patton, Bernard Montgomery and the Post-War World

Epilogue

Notes

Select Bibliography

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

Index

Maps

The First World War, 1914–18: The Western Front

The First World War, Romania, 1916–17

The First World War, Italy, 1917

France and the Low Countries, 1940

North Africa, 1940–1943

Sicily and Italy, 1943

North-West Europe, June 1944–May 1945

Introduction

TOWARDS THE END of his long and distinguished life I visited Field Marshal The Lord Bramall at his home in Hampshire. Although he was over ninety years of age, I found that Dwin, as he insisted I call him, had lost none of his passion for discussing military affairs and, in particular, leadership. His precise and persuasive arguments that morning about what he felt made an effective leader drew heavily from a career that began leading a 35-man platoon in Normandy on 8 June 1944 and ended forty years later as Chief of the Defence Staff, the professional head of the British Armed Forces. As the field marshal plunged deep into history to illustrate the importance of apt leadership styles and why it is vital to win trust, I began to understand more why he was one of the most accomplished military leaders Britain has ever produced.

Dwin deployed an argument as deftly as a general might manoeuvre his principal fighting division, as he expounded on the enduring nature of leadership across the millennia, referencing Bernard Montgomery heavily during our conversation. ‘Monty could be an exceptional leader,’ he explained, ‘with a great talent for putting his message across and getting things done how he wanted – but could also be extremely difficult.’1

There was no doubt that Dwin admired much about Montgomery. The field marshal presented a young Lieutenant Bramall with the ribbon for a Military Cross awarded for his leadership in October 1944, when he cleared a German post with grenades and his Sten gun. Before Bramall met the great man at the presentation, one of Montgomery’s aides had given him some advice: ‘The Field Marshal will ask you whether you and he have ever met before. He will not mind if you say “Yes” or “No”, but he will mind if you say you can’t remember.’2 Dwin chuckled at the memory, shaking his head.

As our discussion progressed, Dwin became keen to discuss what he termed ‘the privilege of responsibility’. Whether leading a small team in combat to seize tactically important ground, or clashing with Whitehall mandarins over the implications of budget cuts, ‘the personal sense of responsibility,’ Dwin expounded, ‘does not feel different and nor does the sense that one is extremely fortunate to be faced with such challenges and looked to by others for a way forward.’

Taking a pause to gather his thoughts but looking me straight in the eye, he continued: ‘It does not matter what one’s appointment is or the tests that one faces, leadership is essential. Leadership underpins everything the Army does and involves everybody. Success is always founded on good leadership while with failure the opposite is very often true. It is vital, absolutely vital, to find a way to inspire men to do the mundane as well as the extraordinary. Yes, inspire is the correct word – inspire and motivate.’ The field marshal then explained how he, and those who inspired him, encouraged men to follow. He emphasized his belief that the methods and style adopted by an individual leader have to take account of many variables if they are to be successful.

Academics David Day and John Antonakis concur, having written that leadership is shaped by ‘the leader’s dispositional characteristics and behaviours, follower perceptions and attributions of the leader, and the context in which the influencing process occurs’.3 Yet while obvious attributes such as moral courage, decisiveness and calmness under pressure are essential for leader effectiveness, it is leadershipskills – such as the ability to communicate, empathize and create an esprit de corps – which will make a leader potent.4 Successful military leaders therefore need to possess both intra- and inter-personal skills if their leadership is to work, and this requires constant attention to the art of leading and constant attention to how they might improve their abilities. As Harry S. Laver and Jeffrey J. Matthews note in The Art of Command, a study of nine commanders from George Washington to Colin Powell: ‘Their careers demonstrate that the quality of one’s leadership ability develops over years, even decades. None of them began their careers in the military as exceptional leaders. They did, however, have the good fortune to serve under effective mentors, and, more significantly, each had the good sense to learn from the examples set by these role models.’5

With each new role, every advance in rank and each new context, it is particularly important that officers and soldiers think again about their leadership and what is demanded of them. While an army will do what it can to prepare individuals for the next stage in their career (for traditionally armies grow their own leaders), selfdevelopment remains indispensable because there is always a need to translate organizational training and education into something that reflects the leader as an individual. Even if enlisted soldiers make up by far the greater proportion of an army, finding time to improve one’s leadership is particularly important to officers because they dominate command appointments in which they have legal responsibility for the ‘direction, coordination and control of military forces’.6 Leadership is an indispensable constituent of command – which makes its own heavy demands on an individual’s professional and personal competencies – but no matter what role or context an officer happens to be working in, proficient leadership drives military effectiveness, for as the ancient Greek writer Herodotus wrote nearly two and a half thousand years ago, ‘Circumstances rule men; men do not rule circumstances.’7 In being recognized as the personification of an army’s values, standards and leadership philosophy, a leader not only creates a positive local climate but helps to reinforce the healthy organizational culture upon which the army’s fighting power depends.8 It is a poorly advised army, therefore, that does not take heed of Jörg Muth’s assertion in his book Command Culture that ‘troops fight the way they are led’9 and, ultimately, fighting is what an army exists to do.

During our discussion about military culture, Dwin Bramall began to speak with great knowledge about the impact of three particular leaders: George Patton, Bernard Montgomery and Erwin Rommel. Born between 1885 and 1891, they came into the world at the height of an industrial revolution which powered the Age of Empire in Europe and the Gilded Age in the United States, and fuelled the First World War. All three officers participated in the 1914–18 cataclysm, and like millions of others, the field marshal emphasized, were so affected by their wartime experiences that it became a fundamental influence on their lives. Yet neither Patton, Montgomery nor Rommel were dissuaded by the carnage from seeking military careers when the guns finally fell silent, and in time the army became their great passion. Each became wholly dedicated to the profession of arms and, being exceptional officers and leaders, they prospered. Yet despite the broad similarities between the three men, there were marked differences in their approaches to leadership due to the individuality bestowed on them by their genes, upbringing, life experience and relationships. Together, these stimuli created three unique personalities – which, in turn, determined each man’s leadership style.10

During our discussion about the complex and nuanced web of what makes one man willingly follow another, the field marshal suggested that I use the lives of Patton, Montgomery and Rommel to reveal ‘the short steps on the long journey of leadership’.11 The result is this book, which seeks, through the eyes of a military historian, to explore the many and various influences that shaped Patton, Montgomery and Rommel as men, as soldiers and, principally, as leaders. It will chart their leadership development through war and peace and through good times and bad. It is a military biography of three officers, viewed through the prism of leadership, as they became among the most prominent officers in their armies and, eventually, in early 1943, all fought in Tunisia. North Africa, however, did not mark the end of the leadership odyssey for Patton, Montgomery or Rommel; it instead acted as a waypoint on the route to a final confrontation in northern Europe, at the end of which, two of these remarkable men would be dead.

CHAPTER ONE

Early Years and JuniorLeaders, 1880s–1914

IN LATE SPRING 1905, the body of shoemaker Hiram Cronk was displayed in the main lobby of New York City Hall. Cronk was given this honour not because he had been 105 years of age at the time of his passing, but because he had been the last surviving veteran of the War of 1812. When his body was finally removed from view (after some 925,000 people visited to pay their respects), Cronk was transported through New York streets lined with thousands of onlookers, in a hearse drawn by four gleaming black horses and escorted by men who had fought in the Civil War. Remarking on a scene that he felt marked the end of a more noble era, the correspondent of West Virginia’s Bluefield Daily Telegraph recorded that the old soldier was ‘the last link connecting the simplicity of Jefferson’s day with the strenuous complexity of the present’.1

The Second Industrial Revolution and the rapid economic growth that accompanied it had ushered in a new age. Advances in manufacturing technology were supported by a rapidly developing railway network that linked modern cities and had, along with the telegraph and telephones, transformed the nation by the dawn of the twentieth century.2 An aspirational society agitated for governmentled reform, while men of influence called for the United States to exert itself more forcefully in the international arena. A stronger, more confident nation with a clear identity had emerged, and it rippled with ambition. By 1905 the balance of the world’s power was shifting, and in this dangerous but opportunity-laden arena George S. Patton, Bernard Montgomery and Erwin Rommel sought to make their mark.

The nineteenth century was filled with dominant figures – colossi that strode the world stage and, whether politicians or generals, artists or businessmen, explorers or sportsmen, kept increasingly literate populations absorbed by their achievements – and in that patriarchal society, exceptionally successful specimens of the male sex were used by their respective nations as inspirational figures in a competitive era. Indeed, in 1841 the philosopher Thomas Carlyle published On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History in which he argued that ‘Great Men should rule and that other men should revere them’.3 Yet while Carlyle believed that ‘the great’ should be role models for the young, he also theorized that their successful emulation was limited to those blessed with inherently ‘heroic’ dispositional traits at birth. A generation later, however, the notion that an individual’s ability to achieve the remarkable was determined solely by what we now know as genetics was challenged by those who postulated that the creation of leaders also depended on the environment into which they were born. In 1873, for example, Herbert Spencer opined in The Study of Sociology that early social conditioning moulded personalities, outlook and approach, and that ‘before [a Great Man] can remake his society, his society must make him’.4

Patton, Montgomery and Rommel were, therefore, born to an era in which the dominant belief was that privileged upper-middle-class professional and aristocratic families alone formed the ‘leadership class’ – for it was thought offspring not only inherited the most favourable genes for the task, but were also exposed to the positive societal influences that were required to develop the necessary traits.

— ¤ —

George S. Patton Jr was born to a wealthy family of high-achievers. In the century before his birth, his ancestors included Brigadier General Hugh Mercer, Democrat congressman John Mercer Patton, and the latter’s son, George Smith Patton – who, with seven of his brothers, fought under the Confederate flag during the Civil War. An accomplished leader who displayed great personal courage, coolness and decisiveness, George Smith Patton was mortally wounded aged thirty-one while commanding a brigade in the Third Battle of Winchester in September 1864. He was laid to rest next to his brother, Waller Tazewell Patton, who himself had died of wounds during Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg in July the previous year, while commanding the 7th Virginia Infantry Regiment.

The stories of their heroism and sacrifice were well known to George Smith Patton’s four children – including George S. Patton, whose impoverished mother, Susan, instilled in him a set of strong values during his upbringing in California. Based on loyalty, hard work and discipline, Mrs Patton’s principles were to stand her son in good stead for his time at the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) during the mid-1870s. There George became the first-ranking officer cadet in his class, before returning to California to study law where, in 1884, he passed the California bar examination and married Ruth Wilson. Ruth was the daughter of the late Benjamin Wilson, one of California’s founding fathers, the first elected mayor of Los Angeles, a great landowner and a successful businessman. Together, George and Ruth raised two children on Benjamin’s glorious Lake Vineyard estate. The first, born on 11 November 1885, was given the Patton family’s traditional name for a first son: George.

‘Georgie’, as George Junior became known, enjoyed an idyllic childhood with his sister Anne (known as ‘Nita’). The pair revelled in the freedom they had to explore the countryside, ride and do whatever else they could find to entertain and exhaust themselves. They were blissfully unaware that their father had sacrificed his burgeoning legal career to run the by-then-ailing Wilson empire and that he constantly struggled to maintain his family’s lifestyle, which included the frequent and lavish entertainment of guests in their large home boasting both servants and stables.

One house guest became a permanent fixture, and worked assiduously to dominate the household. Annie, or ‘Nannie’ as she was known to the family, was Ruth’s tyrannical spinster sister. She quickly established herself as a primary influence on young Georgie, whom she mollycoddled as if he were her own. His parents tolerated this, not least because Nannie was a great stimulant to Georgie’s imagination by encouraging his role-playing of the fictional characters she read about to him from Homer, Scott, Kipling and Shakespeare, as well as historical figures including Alexander the Great, Napoleon Bonaparte, Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson.5 His was an informal education until entering school at the age of eleven, where some previously identified difficulties with reading, writing and spelling were confirmed.

Biographers disagree over the cause of these learning difficulties, some arguing that they were the result of dyslexia while others merely the result of his late entry into school.6 Whatever the cause, the situation demanded that George find ways to overcome the challenges his learning difficulties produced, and he largely succeeded. Although his spelling remained poor for the rest of his life, George S. Patton Jr became a fluent writer and a voracious reader. Nevertheless, his lack of educational ‘normality’, and lack of early socialization with other boys in the formal, structured setting of an educational establishment, did see George marked out as ‘different’ during his early years at school, and therefore vulnerable to peers who pounced unsympathetically on anybody unlike themselves. Consequentially he felt slow, stupid and something of an outsider while at school, and this, in turn, created within him a need for approval, reassurance and acknowledgement.7 These were also circumstances that fuelled George’s fiery desire to succeed and – of great importance to him – not disgrace his family name. An intelligent boy who recognized the value of hard work, in time he was able to successfully manage his complicated relationship with words. Indeed, by the age of sixteen he began the work required to win a coveted place at the United States Military Academy West Point.

Although West Point then trained a minority of US Army officers, a disproportionate number of its graduates achieved the most senior ranks.8 Patton prepared for the gruelling entrance examination while at VMI, and his father set about mobilizing his agents of influence to win for his son the single West Point nomination that his senator, Thomas R. Bard, could make each year. Application to the task and not inconsiderable sacrifice on the part of both Georges led to success: Patton passed the entrance examination in March 1904 and Bard awarded the eighteen-year-old his nomination soon after. This success reinforced in George that, with discipline, industry and the right connections, he could achieve anything he wanted. To that end, George wrote to his father that summer determined that he would become a general, stating, ‘I will do my best to attain what I consider – wrongly perhaps – my destiny.’9

Whatever his destiny, George knew that the four-year West Point course would be a severe test of his body and mind as well as a formative experience. The syllabus was heavily academic with an emphasis on mathematics, the sciences and engineering (to Patton’s chagrin, no specific military history course was offered and nothing on infantry tactics), all delivered in a dry style by passionless military staff who lacked expertise in what they were teaching.10 The academy was less a haven of critical thinking and more a crammer-cum-finishing-school which exalted discipline and drill. George had no difficulty with ‘bull and starch’, but he found the absorbing of vast quantities of knowledge to pass the examinations particularly challenging. Moreover, although he desperately wanted to become a leader, Patton found that West Point offered little developmental opportunity because its officer cadets were admitted on the assumption that they already possessed the necessary traits to be effective leaders. The first (‘plebe’) year was notorious for its ‘hazing’ – bullying by senior cadets – which was designed to break some cadets and help staff identify those who failed to show the required stoicism. The West Point experience, therefore, produced resilient, courageous, disciplined officers with strong academic credentials, but who knew precious little about soldiering, officership or leadership. Indeed, George C. Marshall, the future Chief of Staff of the US Army, later identified the academy as having a negative influence on the Army because it taught ‘how to give commands and to look firm and inexorable’ and, what is more, the cadets ‘largely had to find [their] knowledge of leadership and command from… the disciplining of “plebes”.’11

West Point was very different from the comfortable world Patton had previously inhabited, where his foibles were accepted, his demands acceded to and his intolerances went unchallenged. The narrow-minded and soft young George, therefore, failed to endear himself to his fellow cadets, whom he derided as of ‘lesser character’ and ‘not quite gentlemen’, and he was severely bullied in return.12 Thus, he remained an outsider, devoid of both the close friendships that West Point promoted and the appreciation of his talents that he had come to rely on as a child. Surrounded by capable, bright, fit peers who enjoyed each other’s company, Patton wrote frequent selfpitying letters to his father, including one at the end of 1904 which stated, ‘I am a characterless, lazy, stupid, yet ambitious dreamer; who will degenerate into a third rate second lieutenant and never command anything more than a platoon.’13 Such missives were most frequently written at times of stress or failure, which meant, therefore, that a flurry of letters arrived in California at the end of his first year when, having failed his mathematics examination, he was required to retake the entire year.

Already tenacious and convinced that failing to graduate from West Point was unconscionable, the increasingly obstinate young man redoubled his efforts. In the small black notebook that he took to carrying during his time as an officer cadet in order to record his thoughts, his first entry read simply: ‘Do your damdest [sic] always.’14 Over the next four years, whenever his academic grades dipped – which they frequently did – he managed to raise them just before his examinations. However, he consistently failed to create any warmth between himself and his fellow officer cadets. When promoted to second corporal in the spring of 1906, for example, Patton’s overzealousness and ability to irritate soon saw him demoted to sixth corporal. It was a chastening experience but he gradually recovered the ranks – the West Point staff showing they valued his military demeanour – to become sergeant major in his third (classman) year, and was then promoted into the role he coveted most: regimental adjutant. He was effective in each of these appointments, but never popular because he delighted in punishing the minor infractions of his fellows while boasting that he would be a general by the age of thirty. In the back of a library textbook in April 1909 he wrote an unfinished list titled ‘Qualities Of A Great General’:

1. Tactically aggressive (loves a fight)

2. Strength of character

3. Steadiness of purpose

4. Acceptance of responsibility

5. Energy

6. Good health and strength

7. ____15

By the time he had written these words, Patton had already decided that, like the great generals of history, he would wear a mask of command. This mask, he believed, conveyed an authority that he might otherwise lack, and imbued him with a gravitas and an aura that made his leadership compelling. In George’s case, however, the mask was less a means of changing persona and more a means of making up for his leadership deficiencies – most notably his poor ability to win the respect of his subordinates. However, in adopting what biographer Carlo D’Este has called ‘his authoritarian, macho, warrior personality’,16 Patton remained out of step with other officer cadets, even though he believed they were out of step with him.

Patton graduated 46th in a class of 103 in June 1909, revealing a solid but unspectacular performance at the Academy despite his grand ambitions. He joined the cavalry, a traditional and glamorous organization well suited to an accomplished rider who had admired the dashing boldness of soldiers on horseback since childhood. The greatest immediate challenge facing Patton on commissioning was how to do what West Point had signally failed to prepare him to do: lead soldiers in the field army. During his five years at the Academy he had only very occasionally set eyes on an enlisted man, and had not received training in even the most rudimentary military skills, including shooting.17 As a consequence, when Patton arrived at Fort Sheridan, Illinois, in September 1909 to begin his first tour of duty as a second lieutenant in the 15th Cavalry Regiment, there was some resentment among the men of his platoon that he had the authority and a sense of entitlement but was useless to them. It was essential, therefore, that Patton absorb as much professional knowledge as he could, as quickly as possible, and develop a strong relationship with his non-commissioned officers (NCOs) in the process.

The issue of poorly prepared junior officers was, however, just one of many that beset a US Army whose significant capability deficiencies had been exposed by the Spanish-American War (1898) and the Filipino-American War (1899–1902). The modernization programme that followed was well intentioned, but with a small budget. With its 85,000 officers and men scattered over a panoply of small, rundown garrisons, the US Army remained a demoralized and fragmented force when Patton joined.18 Nevertheless, reform had begun before Patton joined the Army, with the ambition of developing it from an old-fashioned frontier police force into something fit for an innovative nation with growing power and expectations. The structural changes that followed, for example, saw the establishment of divisional formations that made the Army capable of undertaking swift expansion should the need arise. Progress was also made in 1903 with the creation of a General Staff to plan, investigate and coordinate military activity under the auspices of a Chief of Staff of the US Army, the professional head of the service. It was an initiative that gave the Army the cerebral and organizational firepower it had been lacking for so long, and produced a new emphasis on officer development that was designed to better prepare its people for specific career stages. The enterprise included cohered courses which ran in garrison and branch schools, the staff college at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and at the recently created US Army War College in Washington.19 The turn of the century also saw a modern officer career-management introduced with responsibility for promotions, assignments and tours, and rotation between staff and command assignments punctuated by periodic professional training. In sum, the changes were a significant advance in the professionalization of the US Army and, ultimately, were of great advantage to ambitious, energetic and talented officers like George Patton.

Despite the change gripping the Army at the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, there was little to show for it at Fort Sheridan, which remained a small and dilapidated cavalry outpost thirty miles north of Chicago, home to Troop K of the 15th Cavalry Regiment. Patton found a lethargy in the Troop’s attitude to soldiering which, under the mentorship of Captain Francis Marshall – the patient, professional and diligent commander of the unit – he sought to rectify. Second Lieutenant Patton inevitably made some elementary mistakes in the early days of his command, mostly the result of the young officer’s desire to show the qualities of a strong leader rather than ensuring that his leadership was appropriate. Overplaying his rank, being exceedingly officious and losing his temper (particularly during his first introduction to leading soldiers) were all behaviours that had dogged his time at West Point, and now they haunted his platoon until a combination of NCOs and Marshall taught him the error of his ways. The lessons were hard, but Patton absorbed them. On one occasion, having humiliated an enlisted man in front of his colleagues for failing to properly tether a horse, when his rage subsided Patton returned and apologized personally to the man in question and then to all those who had witnessed the unsavoury scene. It was the first of many occasions during his long career in which Patton found it necessary to ask for the forgiveness of subordinates, colleagues or superiors. Marshall pointed out the need for leaders to be aware of their attitudes, behaviours and actions on others rather than merely expecting a positive reaction to an officer with authority. The wise troop leader also recommended that Patton should seek to have greater empathy with his subordinates – not just to be seen as an officer who took an interest, but to be better placed to energize, motivate and inspire them day to day.

Fort Sheridan was a learning ground for Patton in many ways, be it in the art of leadership, the skills that he expected his men to have, or how to use his spare time for self-improvement. To his credit, while other junior officers frittered away long hours loafing in the mess, Patton read deeply, reflected on the profession of arms and engaged in a vigorous theoretical correspondence with friends and colleagues. In so doing he was acting on his own advice, having written in his little black notebook while at West Point: ‘I believe that in order for a man to become a great soldier… it is necessary for him to be so thoroughly conversant with all sorts of military possibilities that when ever an occasion arises he has at hand with out effort on his part a parallel.’20 His assiduous attention to the profession of arms was to become an important part of Patton’s life.

The young officer also found ample time to participate in a range of sports, particularly those involving horses but also fencing and pistol shooting, as well as enjoying a full social life in camp and in nearby Chicago. During his frequent trips to the city he became reacquainted with Beatrice Ayer, the beautiful and talented daughter of an eighty-year-old Boston multimillionaire and a distant relative who had visited Lake Vineyard several years earlier. A romance developed, and in May 1910, after a short courtship, the couple were married at Avalon, the Ayer family mansion in Prides Crossing, Massachusetts. Yet while for the young officer the match required relatively minor changes to his lifestyle, for Beatrice, taking a lowly paid junior Army officer as her husband and swapping comforts and glamorous society for cramped accommodation in the austere Fort Sheridan married quarters, it demanded considerable sacrifice. Beatrice had not only married George S. Patton, she had also married the US Army and she did not find the transition at all easy.

The arrival of the couple’s first child, Beatrice (known as ‘Bee’), in March 1911 did little to improve Mrs Patton’s feeling of dislocation, for although the baby could have strengthened the union with her husband, it instead sent George into a jealous malaise, caused by Bee’s monopolization of her mother, which lasted several months. By the autumn, George had come to recognize that Beatrice was not going to undermine the needs of her child to pamper a selfish husband and he transformed into the doting father that he was to remain, but the episode did reveal Patton’s deep desire to be the centre of attention and his proclivity for bouts of poor mental health.

Although what precisely caused George’s sudden acceptance of his daughter’s needs is unknown, being given temporary command of Troop K in Marshall’s absence may well have shaken him out of his misery. It was followed soon after by more good news – he had been posted to Fort Myer in Arlington, Virginia, just three miles from the White House. His new job with Troop A at the headquarters of the 15th Cavalry Regiment would put Patton within easy reach of the powerful men in the capital city, the society that his wife craved and an opportunity to combine both. Indeed, Fort Myer was the official residence of the Chief of Staff of the US Army and an array of other senior officers, and as soon as Patton arrived in December 1911 he wasted no time in ensuring that their paths crossed. It was a watershed event in Patton’s career and ‘his life and military development entered a wholly new phase, the real beginning of his rise to fame’.21 With their larger and more comfortable quarters, the Pattons hired a full-time maid and a chauffeur to drive the family car, and Patton purchased a thoroughbred horse to add to his own burgeoning stable. He rode each morning for exercise and to make new and prestigious acquaintances. On one such ride Patton met Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, with whom, despite their eighteen-year age difference, he began a friendship that was to last until the end of Patton’s life.

Captain Julian R. Lindsey, the commander of Patton’s troop, must have watched his new subordinate’s approach to life at Fort Myer with some curiosity, because it was flamboyant even for the cavalry. Yet Patton must have revealed more than just an ability to attract attention, for by the spring of 1912 he had been appointed squadron quartermaster, a much sought-after position, and his annual report rated him ‘excellent’ in his attention to duty, professional zeal, general bearing and military appearance, and ‘very good’ for intelligence, judgement, instructing, drilling and handling enlisted men.22 Attentive to his duties but always keen to fill his time constructively, Patton began to write military articles and pamphlets to help develop himself, but also to get noticed. Although his first pieces (such as Principles of Scouting, published in February 191223) were focused on the cavalry and well received, his aspiration was to examine issues of broader interest to the US Army.

Patton’s ambition to be a man of influence was furthered by his selection to represent the United States in the new modern pentathlon event at the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm. As the sport saw all competitors drawn from their nations’ respective armies, the 26-year-old Patton was a natural choice for US selectors looking for an individual adept at swimming, pistol shooting, running, fencing and riding. Although finishing fifth was a frustration for the young officer, the US press gave Patton such significant coverage that by the time he returned he had become something of a celebrity, and he was the toast of prestigious dinner parties at which, as one fellow guest wrote, ‘the young man needed little encouragement to tell his tales of his triumphs’.24 The name ‘Patton’ rippled through Washington society and was known by the Chief of Staff of the US Army, Major General Leonard Wood, who by the autumn of 1912 was a regular on the rides that Patton and Stimson took together. It was company that gave George confidence as well as connections that he might mobilize in the future, but he remained a junior officer with a little local fame that he recognized was based on a limited achievement.

To make a real impact, Patton knew that he had to offer something that others found valuable, and this was also important to his leadership of his platoon at Fort Myer. There, however, he was often left exasperated by his subordinates’ failure to show any improvement in their military skills despite his best efforts to train them. After one particularly unsuccessful day on the ranges, he wrote to Beatrice: ‘Our great trouble is that men do not do what they are told. They think too much! This talk about the independence of the American soldier will cost a lot of lives, if we would teach them to obay [sic] we would do much better than teaching them to shoot.’25 It was a challenge that reinforced his long-held belief that discipline was the cornerstone of military competency, and this had to be laid securely by leaders before a soldier could be commanded, far less led.

Patton was addressing such matters at the end of 1912 by asserting his will directly on those he commanded when, unexpectedly, he was plucked from regimental duties and dropped into a very different context, as a temporary assistant in the Chief of Staff’s office, and became advisor to the Ordnance Department. On his way back from Stockholm, Patton had taken a sojourn at the French Cavalry School in Saumur to learn from the best fencing instructor in the French Army, and now, while waiting for his article ‘The Form and Use of the Saber’ to be published, he assisted in the development of what became known on its issue as the ‘Patton Saber’.26

George Patton’s stock was on the rise, and in the spring of 1913, when his short appointment came to an end, he had every right to feel that, at last, he was making a difference to the US Army as a specialist. His growing knowledge and skill as a swordsman continued with another course at Saumur that summer, following which he attended the Mounted Service School at Fort Riley, Kansas, not only as a student on a career course but also as ‘Master of the Sword’, an instructor to more senior officers on advanced programmes. Learning to use a sword had started with play when Patton was a child but had become a passion, and he had become a stylishly effective swordsman in his twenties. During the first class he delivered at Fort Riley, Patton was keenly aware that he was junior to those he needed to influence and so said, ‘I realize how hard it must be to take instruction from a man you must regard as still a little damp behind the ears. But gentlemen, I am about to demonstrate to you that I have been an expert with the sword, if nothing else, for at least fifteen years, and in that respect I am your senior.’27 He then waved in the air the two wooden swords that he and his sister used to play with as children at Lake Vineyard, to peals of laughter from the watching officers. Patton went on to demonstrate his skill and deep knowledge of swordsmanship, and held his audience in the palm of his expensively gloved hand.

Such were his abilities, moreover, that upon graduation from the course in May 1914, Patton was awarded one of just ten highly coveted places on the school’s Troop Commander’s course. There was no question of him refusing such an invitation even if it did mean more time away from his family and being remote from world events. Thus, as Europe descended into war, and second lieutenants from the belligerent armies took their chances, George Patton looked on enviously from a distant US Army camp in the middle of Kansas.

— ¤ —

Bernard Montgomery was from a solidly middle-class family that unwittingly shaped him into something of a rebel. Born in London on 17 November 1887 to Reverend Henry and Maud Montgomery, the fourth of their nine children, Bernard was expected by his family to contribute to a British Empire that was a source of gloating satisfaction among the privileged classes and of growing envy to international competitors. The Montgomerys could trace their roots back 900 years (although a little tenuously) to the Norman warrior Roger de Montgomeri, a trusted soldier and confidant of William the Conqueror who became one of the most influential men in England in the years after the 1066 invasion. More recently, Samuel Montgomery, Bernard’s great-grandfather, had been a successful Irish merchant who by 1750 had acquired enough wealth to build New Park House on sixty acres at Moville in the northern Irish county of Donegal. Just weeks after Bernard’s birth, the heavily mortgaged New Park was inherited by Reverend Henry after the death of his father, Sir Robert Montgomery, a former Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab. It was a huge financial burden for a junior clergyman, then vicar of St Mark’s in Kennington in south London, who also had responsibility for a growing family. Henry did what he could to safeguard the family seat, but his endeavours demanded significant sacrifices by his children, who grew up in a family for which thrift was a virtue born of necessity. Maud consequently ran the family’s finances while her husband conducted his ministry, allocating him a tiny weekly allowance and asserting a ruthless discipline on all – which was to affect Bernard for the rest of his life.

Maud Montgomery was the daughter of Frederic Farrar, a noted figure in Victorian society, a prolific author, a former head of Marlborough School and an esteemed clergyman who was destined to end his days as canon of Westminster Abbey. Maud met her future husband when she was just a girl and Henry worked under her father as a curate while Frederic was rector of St Margaret’s, Westminster (Parliament’s church). They married in 1881 and were soon producing a family, on which Maud sought to impose strict order and Christian values in what conservatives perceived as a ‘rapidly changing and immoral world’.28 She dominated the Montgomery household while Henry concentrated on his professional duties, which, due to his immense hard work and considerable talents, saw him promoted to Bishop of Tasmania in 1889. It was a great honour but demanded yet more sacrifice from his family, which was summarily uprooted from the urban sprawl when Bernard was two and transplanted to the tiny leafy city of Hobart on the other side of the world.

Here the Montgomery children were home-tutored and left free to explore the local countryside, glorying in their independence. They were always aware, however, that independence was allowed only within the confines of their affectionless mother’s strict rules, which, if broken, would most likely end with a physical punishment. Of all the Montgomery household, Bernard was the most likely to stand up to his mother, which inevitably led to a confrontation between two immensely stubborn individuals and saw him later write, ‘My early life was a series of fierce battles.’29

On returning to London in 1902 when his father took up a new appointment, Bernard and his older brother Donald were enrolled as day boys at St Paul’s, a high-achieving and traditional English public school in London. On his arrival Bernard was not deemed as academically able as the majority of his contemporaries and was placed in what was commonly referred to as the ‘Army Class’ (for, as Montgomery later admitted, ‘In those days the Army did not attract the best brains in the country’30). Bernard worked diligently at his studies, but although he remained a mediocre student in the classroom, he quickly gained a reputation for being a rule breaker who excelled on the games field. Slight, wiry and agile, the young Montgomery had the speed of thought and limb that made him an outstanding rugby and cricket player, while also being one of the school’s top swimmers.

The sporting accolades that came his way over his years at St Paul’s more than compensated for his lack of academic acumen in the eyes of other boys. Nevertheless, Bernard’s extracurricular accomplishments did little to allay the concerns of his parents, who towards the end of his time at the school received a report which stated that their son was ‘rather backward for his age’.31 Young Montgomery, it seemed, was best suited to life as an army officer, and so in the autumn of 1906 he sat the entrance examinations for the Royal Military College Sandhurst (RMC). The fact that Montgomery passed a decent 72nd out of the 177 who sat the examination was all that Henry and Maud needed to confirm that a respectable career awaited their son, and they spared no effort in encouraging him to take up the Army’s offer of a place on its commissioning course.32

The British Army in the first decade of the twentieth century was smarting after the unsettling experience of the 1899–1902 Anglo-Boer War. Although ending in victory against the two Boer republics that were demonstrating their anger at the British Empire’s influence in southern Africa and despite a numerical superiority of nearly six to one, the British had struggled to impose their will in the face of the Boers’ guerrilla warfare. The long and expensive war instigated several official enquiries, the recommendations of which prompted reforms which sought to make the Army more professional and broadly improve its fighting capabilities.33

Considering the increasing threat to Britain offered by Germany’s military build-up and foreign policy ambitions, many influential commentators regarded such developments as not coming a moment too soon. With leadership having been identified as critical in the required transformation, measures focused on improving officer training were among the first to be initiated. Criticisms of the RMC had been made by a government committee which reported in 1902 that the college was more like a public school than an institution designed to turn out military professionals, and led to an immediate overhaul of its syllabus, teaching and assessments.34 The aim, the committee explained, was to ensure that an RMC student was no longer instilled with a dislike of military study ‘which too often remains with him throughout his career’.35 Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in India and founder of the Indian Staff College at Quetta, believed in the objective, as he regretted that there was ‘too often a want of serious study of their profession by officers who are, I think, rather inclined to deal too lightly with military questions of moment’.36

As a consequence, when Bernard Montgomery arrived at the RMC on 30 January 1907 for his twelve-month course, he was entering an institution in the middle of a slew of important changes in how it produced young men fit for the challenge of leading in a twentieth-century army. Montgomery thoroughly enjoyed his early weeks at Sandhurst, was soon promoted to lance corporal, and by the summer was rated ‘excellent’ by the commandant.37 He continued to excel at team sports, performed well in the practical exercises, and enjoyed a syllabus which now included tactics, military history and geography.38 While there was no specific leader and leadership training or education, the entire course was driven by the need to develop an officer cadet’s character and provide him with the basic military skills required in his first appointment. Specifically selected military instructors immediately made improvements to the course, and Montgomery was among the first to attend a new summer camp created to test leadership and practical military skills in the field. Encouraged to excel by the competition engendered by this new breed of instructor, Officer Cadet Montgomery nonetheless very nearly failed to commission.

In December 1907, just before their final examinations, a small group of officer cadets held down a colleague in his room while Montgomery set fire to his shirt tails. The injuries that the young man sustained required his hospitalization, and Montgomery’s castigation was severe. He escaped expulsion from the RMC only after a personal plea by his mother, but was censured, demoted and ‘back-termed’ to repeat the final three months of the course. It was an embarrassing brush with disaster. Checking his behaviour and applying himself to his work, Montgomery eventually passed his examinations to graduate from Sandhurst a creditable 35th out of 150 in the spring of 1908.39 His reward was a commission into the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, a traditional and inexpensive county regiment with a fine heritage in which talent would shine brightly. ‘Monty’, as he was known to friends and colleagues, left Sandhurst and moved away from his family without hesitation, determined to embrace fresh opportunities and a new life.

Second Lieutenant Montgomery’s first posting was to the 1st Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment in the ancient city of Peshawar, then in India and located close to the strategically sensitive North-West Frontier of the British Empire. Threatened by Russia and Afghanistan and frequent raids by Pashtun tribes, the officers and men of the 1st Royal Warwicks had to be on their mettle. As a platoon commander responsible for fifty men, Montgomery soon learned that the culture in the battalion was not sympathetic to idleness.40 It was an excellent environment for his development as a leader, and he set about discovering his troops’ fighting capability and what, as he later wrote, ‘made them tick’.41 He also attended as many courses to improve his own skills and knowledge as time would allow, including musketry, machine gunnery and signals, while also taking lessons in Urdu and the local Pashtu dialect. In every spare moment, rather than relaxing in the mess with his peers, Monty read a wide range of books, articles and Army publications that would provide him with a better understanding of his profession. This distinguished him from most other officers in the battalion, but as he later wrote, ‘Looking back, I would put this period as the time when it was becoming apparent to me that to succeed one must master one’s profession.’42

As a junior leader, Montgomery was particularly keen to understand his soldiers and how to interact with them, paying particularly careful attention to his communication skills and what worked best to get a certain effect.43 Many of his fellow officers treated the enlisted men with undisguised scorn and then complained that they were disobedient, whereas Montgomery endeavoured to be respectful and to show that he valued the efforts of his platoon. ‘The men were splendid’, he later wrote, ‘they were natural soldiers and as good material as anyone could want. The British officers were not all so good.’44

His general disapproval of his fellow officers was based on the lack of professionalism that he judged to pervade the battalion, for although everybody seemed busy, he saw plenty of socializing and administration but precious little dynamism. Montgomery did not drink, nor did he enjoy the gossip or childish games that were endemic in an officers’ mess that proscribed talking ‘shop’ and junior officers speaking their minds. To his peers, Montgomery was seen as a bit of a bore, too intense and too obviously energetic. Clement Tomes, a fellow subaltern, later recalled ‘it is [Bernard’s] keenness that seems to stand out most in my memory’, while others felt he got too close to his men and derided his decision to ape his men by tattooing his forearms.45 But Montgomery did not particularly care to be like other officers unless he could see a purpose in it, and far from being concerned about his colleagues’ sneering remarks about his behaviour, he luxuriated in the knowledge that his platoon was developing into the best in the company and one of the most capable in the battalion.

From the outset of his career, Bernard Montgomery did not court popularity but rather respect, for he sought not to be measured by some mistaken belief in the need to conform but purely on his results. Had his sporting prowess not been quite so compelling, Montgomery may well have found himself exiled by his brother officers – a situation that was to be avoided at all costs in the complex world of the regimental family – but instead he was perceived as a distinctly odd young man, although with an attention to detail, self-discipline and sporting talent that demanded he be tolerated.

One of the traits Montgomery displayed while still in his first appointment that was sure to have raised an eyebrow among his fellow officers was his blatant ambition. Although promoted to full lieutenant in April 1910, he remained frustrated that, like in most other armies, promotion in the British Army was not predicated on talent but on time served (seniority) when a vacancy was open.46 Montgomery reacted in the only way he could, to patiently make the most of the opportunities that came his way and to prepare assiduously for the day when his responsibilities would broaden. He therefore revelled in the battalion’s move south to Bombay in October 1910 for its final two years of overseas duty. ‘Bombay!’ wrote a fellow officer at this time. ‘It is the one station in the whole British empire about which nothing good has ever been heard.’47 But Montgomery expected only useful challenges.48

The port city was a cauldron of humanity. Populous, vibrant and offering many temptations to the troops, it was also home to notoriously poor military facilities and sliding standards. Soon Montgomery was spending considerable time on disciplinary issues and had to finally accept that his moral standards were not shared by his men. Nevertheless, he seems to have been content to accept the behaviours that he found distasteful (including drinking, fighting and using prostitutes) if they did not undermine military performance.

This was a practical compromise that Montgomery was to make time and again through his career, because he saw no advantage coming from ‘fighting a tide of well-set attitudes without good cause’.49This, it seems, was appreciated by his platoon, who worked hard for their officer in what he called a ‘quid pro quo sort of arrangement’.50 Montgomery was particularly keen to ensure healthy competition among his men, and established prizes for the best platoon shot and the 200-yard dash. Thus, when appointed the battalion’s sports officer and the German battleship Gneisenau arrived in port with the Crown Prince abroad, Montgomery immediately challenged its crew to a football match. Ignoring advice from headquarters to field a weakened side, Lieutenant Montgomery oversaw a 40-0 drubbing of the opposition, and justified his ruthlessness to a fellow officer by saying, ‘Oh! I was taking no risks with those bastards.’51

By the time the 1st Royal Warwicks finally left Indian shores for England in November 1912, nobody was more relieved than Montgomery. Although his time overseas had been an excellent place to develop his leadership, he had become ever more irritated by being in what he perceived as a military backwater at a time when Europe was edging towards war.52 Montgomery’s next posting was to the battalion depot at Shorncliffe on the south coast of England, from where he could see the French coastline on a clear day. As assistant adjutant he did not get integrally involved in the training that took place at the camp, but it was a position that gave him his first taste of staff duties, a strong understanding of the workings and relationships within headquarters, and it put him in close proximity to the commanding officer. Recognizing that he would likely revert to platoon command should war break out, however, Montgomery pushed hard to be sent to an infantry officers’ course at the School of Musketry (where he received a distinction) and then to a machine gunnery course to further develop his technical skills.

This was a dedication to his profession which was noticed by Captain B. P. Lefroy, who had just returned to regimental duties having attended the Camberley Staff College and soon found himself informally mentoring the enthusiastic Montgomery. So valuable was the relationship that Montgomery wrote, decades later, ‘All this goes to show how important it is for a young officer to come into contact with the best type of officer and the right influences early in his military career.’53 Lefroy seems to have fuelled the young officer’s ambition, reinforcing that hard work would pay dividends, and left him keen for greater responsibility. As Monty’s biographer, Nigel Hamilton, has said: ‘[Montgomery’s] genius lay not so much in his natural gift for leadership – a quality not lacking in English history – as in his deliberate, almost insane pursuit of his goal: a goal he would achieve by unending pursuit of clarity and ruthless self-discipline.’54

— ¤ —

Erwin Rommel was born on 15 November 1891 in Heidenheim an der Brenz, an attractive provincial town in the state of Württemberg, in the south-western German region of Swabia. Renowned across the nation for being inhabited by unemotional, shrewd and hard-working people, Swabia enjoyed a distinct culture and had a suspicion of all things Prussian. The Rommels were a middle-class family broadly illustrative of these regional characteristics. Erwin’s father – also named Erwin – was a mathematics teacher (as was his father) who rose to become headmaster of the secondary school in nearby Aalen. Erwin’s mother, Helene, the daughter of an ennobled civic dignitary, was a housewife who bore five children. Erwin was particularly attached to his mother and she encouraged her small, pale, weak-looking son to explore the outdoors. ‘As far as I can recall’, Erwin wrote in his late teens, ‘my early years passed very pleasantly as I was able to romp around our yard and big garden all day long.’55 A natural athlete whose strength and stamina belied his puny appearance, he came to enjoy a range of sports, including rock climbing, hiking, running, skiing, cycling and swimming. Erwin’s strength and endurance were a source of wonder to those who expected less from a boy of such a diminutive stature, but exposure to his fiercely competitive character soon made them aware that he was a fighter who never gave up and most definitely did not like to come second.

Erwin’s love of the outdoors and his fighting spirit made the Army an obvious career choice for him in an age when the institution was so highly regarded in Germany, but he was not immediately drawn to it. His supportive parents were not wealthy, nor did they expect more of their son than the sort of success that was respectable for his class. Erwin was an average student – poor at those subjects in which he had little interest, but good at those that captured his imagination. With his strong grades in maths and science, Erwin was initially drawn to a career in engineering, and at age fourteen he constructed a full-sized glider with a friend which they managed to coax into flying a short distance. Ultimately, however, young Rommel joined the German Army, hoping that he might be able to combine his practical mind with a life in the open that could satisfy his growing desire for excitement.56 It was also a solidly middle-class profession of which his parents approved, because a generation earlier the Army had provided the basis for a renewed national identity and unbridled ambition.

Indeed, young Erwin grew up in a nation with a booming economy and an intention to create a great overseas empire, which together were bound to antagonize the status quo. The establishment of a powerful army was, therefore, a considered investment in the future, and even the dour Swabians recognized the opportunities that the organization offered. Rommel’s father did not hesitate in writing him a letter of recommendation to the artillery unit with which he himself had served during his compulsory military service. The Army vacillated before accepting Rommel, for no matter what his accomplishments, the selection of a Swabian teacher’s son was not particularly attractive for an organization that was dominated by elitist Prussian standards, as that state was its largest and most instrumental contributor. Rommel was eventually offered a place to train as an officer, but not in one of the more fashionable arms or regiments, nor even in a technical arm such as the artillery, but instead in the line infantry where demand was highest and social standing mattered least. Having accepted an invitation to become an officer cadet in the 124th Württemberg Infantry Regiment, he was told to report to its base in the attractive medieval garrison town of Weingarten – and there, on 10 July 1910, Erwin Rommel began his Army career.

At 622,483 officers and men, the German Army that Rommel joined was developing to meet Germany’s foreign policy ambitions.57 This expansion was overseen by the Chief of the General Staff, Helmuth von Moltke (the Younger), who sought to ensure that when fully mobilized the Army could expand rapidly to 4 million.58 In peace, the armies of four kingdoms of the united Germany (Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony and Württemberg) kept their own identities, but in time of war they would come together as a single entity commanded by the Kaiser. Prussia contributed 75 per cent of the German Army’s manpower, but its broader influence stemmed from its long military tradition and recent military successes. Reforms enacted by the likes of August Neidhardt von Gneisenau, Gerhard von Scharnhorst and Carl von Clausewitz in the wake of Prussia’s defeat by France in 1806 had been introduced by Moltke (the Elder), and were the platform on which victories against the Austrians in 1866 and the French four years later were constructed. By 1871, Germany was unified, and the Prussian Army had become a model of modern military professionalism.