9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

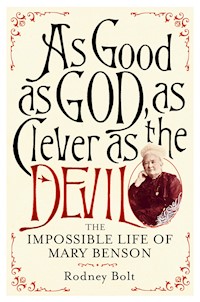

Young Minnie Sidgwick was just twelve years old when her cousin, twenty-three-year old Edward Benson, proposed to her in 1853. Edward went on to become Archbishop of Canterbury and little Minnie - as Mary Benson - to preside over Lambeth Palace, and a social world that ranged from Tennyson and Browning to foreign royalty and Queen Victoria herself. Prime Minister William Gladstone called her 'the cleverest woman in Europe'. Yet Mrs Benson's most intense relationships were not with her husband and his associates, but with other women. When the Archbishop died, Mary - 'Ben' to her intimates - turned down an offer from the Queen to live at Windsor, and set up home in a Jacobean manor house with her friend Lucy Tait. She remained at the heart of her family of fiercely eccentric and 'unpermissably gifted' children, each as individual as herself. They knew Henry James, Oscar Wilde and Gertrude Bell. Arthur wrote the words for 'Land of Hope and Glory'; Fred became a hugely successful author (his Mapp and Lucia novels still have a cult following); and Maggie a renowned Egyptologist. But none of them was 'the marrying sort' and such a rackety family seemed destined for disruption: Maggie tried to kill her mother and was institutionalized, Arthur suffered numerous breakdowns and young Hugh became a Catholic priest, embroiled in scandal. Drawing on the diaries and novels of the Bensons themselves, as well as writings of contemporaries ranging from George Eliot to Charles Dickens, Rodney Bolt creates a rich and intimate family history of Victorian and Edwardian England. But, most of all, he tells the sometimes touching, sometimes hilarious, story of one lovable, brilliant woman and her trajectory through the often surprising opportunities and the remarkable limitations of a Victorian woman's life. Previously published under the title As Good As God, As Clever As the Devil.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Rodney Bolt was born in South Africa. He studied at Rhodes University and wrote the play Gandhi: Act Too, which won the 1980 Durban Critic’s Circle Play of the Year Award. That same year he won a scholarship to Cambridge and read English at Corpus Christi. He has twice won Travel Writer of the Year awards in Germany and is the author of History Play, an invented biography of Christopher Marlowe, and The Librettist of Venice, a biography of Lorenzo Da Ponte, which was shortlisted for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. He lives in Amsterdam.

‘Mary Benson is... a woman whose personality shines off the page... My only complaint about Rodney Bolt’s consistently absorbing study is that it isn’t twice as long.’

D. J. Taylor, Independent

‘Utterly absorbing... It’s a rich weave, and it’s devilishly good.’

Alexandra Harris, Guardian

‘One of the most riveting biographies you’ll read all year... often screamingly funny.’

Lee Randall, Scotsman

‘Surprising... entertaining... This fascinating book does a brilliant job of revealing just how permissive Victorian society actually was. As Bolt shows, as long as you didn’t frighten the horses or alarm the servants, you could get away with pretty much anything.’

Daisy Goodwin, Sunday Times

‘It is impossible to resist a book that begins “On Sunday, October 11 1896, Edward White Benson, Archbishop of Canterbury, insufferable to the end died on his knees in church saying the Confession, ending a life of relentless success.” Rodney Bolt’s focus, however is not on the relentlessly successful Archbishop, but instead his wife, Mary, ecclesiastical helpmeet, child bride, passionate lover of women and mother to a clutch of “hopelessly literate” offspring – an Egyptologist daughter, Margaret; A. C. Benson, author of benign homiletics and the words to Land of Hope and Glory; Hugh Benson, writer of sensationalist Catholic fiction and famed melodramatic preacher, “the Mrs Patrick Campbell of the pulpit”; and E. F. (Fred) Benson, of immortal Mapp and Lucia fame... Yet despite this extraordinary cast of characters, it is Mary herself who remains centre stage, her life almost an apotheosis of all this is disturbing in the Victorian period... Indeed [Rodney Bolt’s] tone is carefully judged throughout, both affectionately admiring of his subject, yet astringently objective. The cleverest women in Europe and her remarkable brood are fascinating to read about.’

Judith Flanders, Sunday Telegraph

‘Bolt has achieved an unusual but extraordinarily successful mode of biography. He brings alive the Benson circle... A fascinating book on an uncommonly brilliant family.’

Sarah Bradford, Literary Review

‘Mary Benson’s insight and intelligence make the story of her life and her extraordinary family a compelling one. I found Rodney Bolt’s engagingly written book very hard to put down.’

Jane Ridley, Spectator

‘Effervescent... At the heart of this book is an extraordinary woman... who deserves to be written and read about.’

Independent on Sunday

‘Rodney Bolt’s chatty, detailed and readable prose paints a vibrant portrait of the multi-faceted human being behind the persona of a Victorian matriarch.’

Metro

First published in hardback as As Good as God, As Clever as the Devil: The Impossible Life of Mary Benson in Great Britain in 2011 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition, The Impossible Life of Mary Benson: The Extraordinary Story of a Victorian Wife, published in 2012 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Rodney Bolt 2011

The moral right of Rodney Bolt to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 184354 862 1 E-book ISBN: 978 085789 582 0

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Love is God

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

The Benson Line

A Word on the Book

Prologue

PART I Minnie

PART II Mrs Benson

PART III Ben

Acknowledgements

Notes

Select Bibliography

Index

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

p.11 Edward White Benson (Senior) and Harriet Benson. A. C. Benson, The Life of Edward White Benson, Sometime Archbishop of Canterbury, Vol 1, 1899.

p.27 Mrs Mary Sidgwick. A. C. Benson, The Life of Edward White Benson, Sometime Archbishop of Canterbury, Vol 1, 1899.

p.46 Mary Benson. E. F. Benson, Mother, 1925.

p.47 Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species, 1859.

p.52 Revd E. W. Benson and his wife. Reproduced by permission of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, MS. Benson adds 19, (#14 & #15).

p.60 Wellington College. A. C. Benson, The Life of Edward White Benson, Sometime Archbishop of Canterbury, Vol 1, 1899.

p.63 E. W. Benson. A. C. Benson, The Life of Edward White Benson, Sometime Archbishop of Canterbury, Vol 1, 1899.

p.71 ‘Willie We Have Missed You’. Public Domain.

p.74 The Doubt: Can These Dry Bones Live? by Henry Bowler, 1855. The Granger Collection/Topfoto.

p.82 Elizabeth Cooper with Hugh. A. C. Benson, Hugh, Memoirs of a Brother, 1915.

p.90 The Benson family at Wellington College. A. C. Benson, The Trefoil, 1923.

pp.108–9 Sketches in letters from Mary Benson to Ellen Hall. Reproduced by permission of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, MS. Benson 3/40, fols 182, 184.

p.114 Nellie and Maggie. A. C. Benson, Life and Letters of Maggie Benson, 1917.

p.139 Maggie with some of her pets. A. C. Benson, Life and Letters of Maggie Benson, 1917.

p.143 The Family at Lis Escop. A. C. Benson, The Trefoil, 1923.

p.172 Fred Benson. E. F. Benson, Our Family Affairs 1867–1896, 1920.

p.174 Ethel Smyth. World History Archive/Topfoto.

p.205 Maggie Benson. A. C. Benson, Life and Letters of Maggie Benson, 1917.

p.210 Maggie with Nettie Gourlay. A. C. Benson, Life and Letters of Maggie Benson, 1917.

p.229 Sketches from Hugh’s Egyptian diary. Reproduced by permission of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, MS. Benson 1/58, fols 151v, 159v.

p.233 Queen Victoria celebrates her Diamond Jubilee. Topfoto.

p.242 Mary Benson with Maggie. A. C. Benson, Life and Letters of Maggie Benson, 1917.

p.246 Motorized delivery wagon. Mary Evans.

pp.248 & 251 Tremans. Reproduced by kind permission of the websmaster at horstedkeynes.com.

p.264 A visit to Tremans. Reproduced by kind permission of the websmaster at horstedkeynes.com.

p.271 The ‘Boys’ at Tremans. A. C. Benson, Hugh, Memoirs of a Brother, 1915.

p.299 Beth. A. C. Benson, The Trefoil, 1923.

p.311 Mary Benson. E. F. Benson, Mother, 1925.

THE BENSON LINE

A WORD ON THE BOOK

The Bensons were hopelessly literate. The offspring of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Edward White Benson, and his wife Mary, formed (said the composer Dame Ethyl Smyth) an ‘unpermissibly gifted family’. Mary Benson’s children wrote their own magazine, played word games incessantly, kept scrapbooks of stories and poems. As adults, they became so prolific that their sister Maggie remarked: ‘Some of the family really must emigrate, or English literature will be flooded.’ Maggie produced a philosophical treatise and an archaeological study of the Egyptian Temple of Mut. All three of her brothers wrote novels. A. C. (Arthur) Benson also published poems – most notably the words for ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ – as well as literary essays, biography and uplifting musings. E. F. (Fred) Benson is today best known for his ‘Mapp and Lucia’ books, but his vast literary output also included history, biography and writing about sport. None of them ever married. As Maggie once commented: ‘The odd burst of books in a non-marrying family is better than marriage.’ Mary Benson did not herself join this literary whirligig, but in the novels of her children and in their biographies she frequently flashes by.

In all manner of ways, the Bensons wrote about themselves. Arthur produced biographies of their father the Archbishop, of brother Hugh and of Maggie. Fred wrote one of their mother (though it is largely about himself); both brothers wrote books on the family as a whole, and Maggie came up with one about their pets. Members of the family appear, thinly disguised if at all, in their fiction. Characters may even bear the names of the author’s real siblings. Yet they were a reticent family, locked up and guarded in their relations with others, often not really even in touch with themselves. They fudge issues in their biographies and tell truths in the fiction; sometimes delude themselves in their diaries yet unwittingly reveal themselves in their letters.

When Arthur writes a beautiful account of a childhood walk with his father, something in his tone – and in the eulogizing nature of Victorian biography – creates a niggle of doubt; when, in his novel Memoirs of Arthur Hamilton, the boy Arthur writes ‘I hate Papa’ on a piece of paper and buries it in the garden, the incident has an aura of autobiographical authenticity. The Bensons’ writings present an acute version of a well-worn but nonetheless enduring problem, that of the tricky relation between an author’s life and work. It is an issue that often leads to tiresome speculation – something I have hoped to avoid. Yet the Bensons, who were at times quite open about the autobiographical nature of their novels, do present something of a special case. When it comes to their own work, one feels, the truth frequently lies somewhere in the interstice between the biography and the fiction.

In grappling with this problem, I became inspired by the idea of a commonplace book – those all-purpose notebooks so beloved of writers, where one page might contain a poem that has caught the eye, another a striking phrase or two, or the opening lines of a novel, and yet another a laundry list. I have also found myself imagining a Benson family scrapbook, full of drawings and word sketches, photographs, memorabilia and stories. These ideas suggested a structure that at the very least would deal with the old problem in a different way.

On the banks of the stream that was Mary Benson’s life, I have placed paragraphs of fiction, something to note as you pass by – extracts that may throw a more penetrating light on the flow of the non-fiction. These are an open admission of what has influenced my perception, placed there in the hope that they might contribute a shade or two to the reader’s own. As the idea of a commonplace book grew in my mind, I decided, in addition to extracts from Benson novels, to include further Bensonia, fragments compiled from contemporary sources, as well as other images and writings that may briefly divert attention and, without labouring a point, simply say, ‘Think on this for a moment’ – items that might give a context, provide an illustration, or even a note of contradiction; passages that caught my own eye along the way, and might take the reader on a similar journey. All the while, the main thrust of the narrative tells Mary Benson’s story.

There is a sense in which all biography contains an element of fiction, is an imagined truth created from the available base of verifiable facts. At one end of the spectrum are those impressive, scholarly studies that record almost all known data and every notable event of a subject’s life. This is not such a book. Nor is it a broad cultural history of the subject’s times. Its focus is domestic and intimate; its aim to paint a personal portrait of a woman, her marriage, her loves, the trials of her spirit, and of her vivid, difficult, ‘unpermissibly gifted’ family.

Rodney Bolt

Amsterdam 2011

PROLOGUE

On Sunday, 11 October 1896, Edward White Benson, Archbishop of Canterbury, insufferable to the end, died on his knees in church saying the Confession, ending a life of relentless success.

At that moment his wife Mary – ‘Ben’ to her intimates – became nobody. Life as consort to the Archbishop had been led in a ‘thunderous whirlpool’, a ‘beating fervent keen pulsating life’, of queens and countesses, of discussing politics with prime ministers and dining with poets laureate. William Gladstone had proclaimed her ‘the cleverest woman in Europe’; Queen Victoria had on occasion affectionately foregone the royal ‘we’. ‘All this is over,’ Mary wrote in her diary, ‘it has fallen to pieces around us.’

Edward White Benson had ruled over his wife, from the moment he wooed the young Minnie Sidgwick (as Mary then was) and throughout their marriage. His death created a vacuum not of intimacy, but of meaning. ‘There is nothing within, Good Lord, no power, no love, no desire – no initiative,’ she declared. ‘He had it all and his life entirely dominated mine. Good Lord, Good Lord – give me a personality.’ As Mrs Benson, Mary had held gleaming pearls, ‘always on one string, worn, carried about till they seemed as if they had some real coherence. In a moment the string is cut – they roll to all corners of the room – a necklace for glory & beauty no longer, but just scattered beads. Who will string my life together once more?’

When Ben woke up one morning a few days after her husband’s death, Lucy Tait, beside her in bed, was already helping her to find an answer. Lucy, the daughter of Edward Benson’s predecessor as Archbishop, had long been part of the Benson household. By the time Edward was buried, and Ben and Lucy were seeking respite in Egypt, Ben could assert: ‘I have never had time to be responsible for my own life. In a way I feel more grown up now than I ever have before – strange, when for the first time in my 55 years I am answerable to nobody no-one has the right to censure my actions, and I can do what I like. What a tremendous choice!’

PART ONE

MINNIE

CHAPTER ONE

Little Minnie Sidgwick was eleven years old in the spring of 1852. She was a sunny child, plump, high-spirited, nimble of mind, gay and adventurous. ‘Minnie is more volatile than her brothers,’ she overheard her mother remark. Minnie was a little frightened of her mother.

Not too long ago, Minnie had called herself ‘Mama’s ickle tresor’. She said she loved her mother, as a daughter should. Mrs Sidgwick spoke firmly about duty. She was inclined to check the child’s natural frivolity. Yet little Minnie was not simply inclined to pleasure; she desired to please. She did not like church, but she said her prayers obediently enough. Her mother wanted her love. Minnie hated disappointing her.

Mrs Sidgwick was practical, matter-of-fact and a formidable trainer of servants. She was fond of moral maxims. ‘There’s many a poor person would be thankful for that,’ was one, or: ‘I cannot understand people caring for luxuries.’ Luxury for Minnie – extreme luxury, to the point even of wicked indulgence – came in the form of the simultaneous enjoyment of a soft chair, a book and an orange. Love, warmth and comfort were to be found in the person of her nurse, Beth, a wiry, twinkle-eyed Yorkshirewoman.

Minnie’s father was dead. She did not remember him at all, as he had gone when she was just a few months old. Her favourite brothers, Henry and Arthur, had but a hazy recollection of him, perhaps conjured for them by portraits and family conversation, but the eldest, William, had known him. Papa had been a headmaster in Yorkshire, near their grandfather’s home of Skipton Castle, but Minnie and her family were now planted comfortably in one of the elegant new houses overlooking Durdham Down, on the edge of Bristol, together with her cousins Ada and Eleanor, her maiden aunt Etty, Nurse Beth, Frisk the dog and a canary called Dickey.

Cousin Edward arrived on a visit a short while before Minnie’s eleventh birthday. Edward belonged to the mature, mysterious world inhabited by Minnie’s mother and aunts, having reached the advanced age of nearly twenty-three. He was Ada and Eleanor’s elder brother. Their father and Minnie’s father had been cousins, so really that made Edward and Minnie second cousins. He was at Cambridge. He was quite the dandy (his accoutrements for chapel included lilac gloves and a silk necktie decorated with flowers and toucans) and he was strikingly beautiful. He had long, abundant, light golden-brown hair, pale blue eyes under a high forehead, a straight, noble nose and a mouth like an angel’s, which curved and dimpled delicately at the corners. His face danced with eager, active looks, and he blushed frequently, through sheer pleasure. Minnie’s bachelor uncles in Yorkshire were besotted with him, as was the household at Bristol.

On an earlier visit, when Minnie was only eight, she had impressed Edward by reciting from memory one of Lord Macaulay’s Lays of Ancient Rome, hundreds of energetically rhythmic lines of poetry peppered with Latin names. This and her knowledge of ‘Bible history and English history. . . to say nothing of geography, and writing and drawing’ had so delighted Edward that he submitted her to ‘a good examination in Latin grammar, to the end of the pronouns’. Minnie had passed.

On this visit, Minnie’s ‘mighty favourite’ was Sir Walter Scott’s The Lord of the Isles. She loved poetry and relished the romantic and adventurous. Though she was a little dumpy in her ballooning girl’s skirt and sausagey ankle-length pantaloons, and a touch plain with her full cheeks and straight, dark hair, Minnie’s brightness, bubble and verve transformed her features. As she read The Lord of the Isles for Cousin Edward, he was struck by ‘the keenness and depth of her thought: how her eye would flash with a fine expression, and the really striking voice and gestures with which she would read through a fine passage’. She also read to him from Tennyson’s The Princess, and he was much moved by the Prince’s declaration that a man who does not love a woman leads a ‘drowning life besotted with sweet self. . . Or keeps his wing’d affections clipt with crime’. Love, the inspiring homily continued, encourages men and women to grow together, each absorbing the strengths of the other, a man to ‘gain in sweetness and in moral height’ (women being morally superior to men in their lack of sordid urges), and a woman (given her naturally weaker mind) to expand in ‘mental breadth’ – until at last ‘she set herself to man / Like perfect music unto noble words’.

One night, as little Minnie half lay on the sofa on which Cousin Edward was sitting, she asked him:

‘Edward, how long will it be before I am as tall as if I was standing on that stool?’

‘I don’t know very well, Minnie, five years perhaps. . . ’

‘When I am twenty I shall be taller than that?’

‘Yes.’

‘When I am twenty, how old shall you be?’

‘Thirty-two.’

‘Thirty-two! Edward, I shan’t look so little compared to you, shall I, when I’m twenty and you’re thirty-two, as I do now that I’m eleven and you’re twenty-three?’

‘No, no, you won’t, Minnie.’

‘This unexpected close [of the conversation] made me blush indeed,’ wrote Edward in his diary, ‘and the palms of my hands grew very hot.’ A few nights later, he spoke to Mrs Sidgwick, saying that ‘if Minnie grew up the same sweet and clever girl that she was’ he should like to make this ‘fine and beautiful bud’ his wife.

FROM THE PROLOGUE OF ALFRED TENNYSON’STHE PRINCESS

She tapt her tiny silken-sandal’d foot:

‘That’s your light way; but I would make it death

For any male thing but to peep at us.’

Petulant she spoke, and at herself she laugh’d:

A rosebud set with little wilful thorns,

And sweet as English air could make her, she:

But Walter hail’d a score of names upon her,

And ‘petty Ogress’, and ‘ungrateful Puss’,

And swore he long’d at college, only long’d,

All else was well, for she-society.

Cousin Edward’s visit concluded in a most exciting manner. One Wednesday evening at the end of March, just a few days after Minnie’s birthday and the day before Edward’s examination results were due to be published, the family sat down to dinner with Edward at the head of the table. He was in the middle of telling a long story when Chacey the butler came in, coughed quietly and said: ‘If you please, sir, a gentleman from Cambridge wishes to see you.’ An old man called Mr Martin, swathed in coat and shawls and still carrying his hat and carpetbag, followed, somewhat breathless. Edward fell silent. Mr Martin greeted them all, then said something to Edward that made Minnie’s cousin leap about the room and have to hold on to the doorpost to support himself. Frisk the dog, excited by all the rumpus, seized Edward’s trouser leg and growled and shook until he had to be pulled off. Mr Martin grasped the young man’s hand, stroking, kneading and folding it until it was quite numb. Mr Martin, it transpired, was the Bursar of Trinity College, and Edward’s most affectionate protector. His great news was that Edward had won the Senior Medal in the Classical Tripos, the highest of university honours.

A week later, Edward took leave of the family in Bristol and returned to Cambridge.

CHAPTER TWO

Edward White Benson had been fourteen when, in 1843, his father died, leaving a widow and seven children with a very modest income and a patent for the processing of cobalt.

Edward White Senior had studied privately with the chemist and astrologer Dr Sollitt of York back in the 1830s, then experimented in his home laboratory and come up with, amongst other discoveries (and not without the odd window-shattering explosion), a method of making carbonate of soda, and a new process for producing white lead and cobalt for colouring paint. In 1838 he established the British White-Lead Company, with a large factory amidst the flowers and open countryside of Birmingham Heath, but after an initial spurt of success the business ran dry of capital. The company failed in 1842, and Edward White died a few months later, reportedly of an internal canker but quite possibly, given the toxic substances with which he had surrounded himself for much of his adult life, from poisoning. His business partners offered his widow lifetime use of the family home (which was attached to the deserted factory) and a small annuity. Young Edward – or ‘White’ as he was more often called then – was able, just, to continue as a day boy at King Edward’s School in Birmingham, where he had been a scholar since the age of eleven, and where he developed a respect that amounted almost to worship for his headmaster James Prince Lee.

THE CURIOUS CASE OF DR SOLLITT OF YORKA true tale of the black arts

The great Dr Sollitt of York cast nativities with some success. He was a scholar and magician, and much else besides. Witness what happened in Woodstock some years before Victoria was Queen, at the house of the family of the doctor’s acolyte, Edward White Benson, a chemist of Birmingham. Dr Sollitt had long studied the ways of the Evil One, and perusal of his books had led him to believe he could himself summon the Prince of Darkness. In his chambers at Woodstock he drew a circle and went so far in the requisite incantations as to have recited the Lord’s Prayer backwards. At this moment he was most violently called in the house, and in dread of detection if any one should come to look for him and find himself either excluded or admitted, the dark doctor rushed instantly out of the room. Scarcely had he reached the lowest stair, when a wonderful crash was heard in the room he had just quitted. The whole household ran thither, and it was found that not a single article of furniture, literally, was in place. They all lay overturned on the floor. So perturbed by this event was Dr Sollitt that he forswore his art and made a solemn bonfire of his books. And indeed his acolyte Edward White Benson, too, whenever then or later convinced that he had by Astrology acquired such information of future events as he believed improper for a man to attain, he desisted and burned his books also. This tale is true, as told by said Benson to his son, who became Archbishop of Canterbury.

‘White’ had been a Benson family name for three generations. Young Edward’s grandfather, Captain White Benson, was named after Francis White, the unmarried whist partner of his father, one Edward Benson of Ripon. Francis White had bequeathed his entire estate to his card-playing friend, and Edward Benson of Ripon named his son White in gratitude. This young man (later to be Captain White Benson) married his first cousin, Eleanor Sarah Benson. Eleanor was the sister of Ann Sidgwick (née Benson), little Minnie Sidgwick’s ancestor at Skipton Castle. The son of White and Eleanor, Edward White, the patent holder of cobalt processing, married Harriet Baker, of a staunch Unitarian family. He had a well-developed sense of humour – he once opened a commonplace book with a Pindaric Ode on a Gooseberry Pie – but he was also the author of a book entitled Essays on the Works of God and a fervent Evangelical. Harriet reluctantly joined the Church of England in deference to her new husband.

SILHOUETTES OF EDWARD WHITE BENSON (SENIOR) AND HARRIET BENSON

Young Edward White was their first son – pale and sickly, averse to games, and supremely sensitive. A picture of Bottom wearing an ass’s head in a copy of A Midsummer Night’s Dream struck him dumb with terror and gave him nightmares for weeks; the cry of a wounded hare during a shooting party made him immediately sick, and he swore an oath never to take up a gun in sport. But he was a talkative child, chattering away to strangers and conjuring the most ‘monstrous figments’ – for which untruths he was frequently beaten. He remained ‘White’ until a long summer holiday with his Sidgwick cousins in Yorkshire so improved his health and gave him such a tan that the family joked that his name no longer matched his appearance, and that he should be called Edward instead. He was then interchangeably ‘White’ and ‘Edward’ until his twenties, when the latter stuck.

In his teens, and particularly after his father died, Edward grew increasingly fervent in his faith, gathering around him like-minded friends for whom discussion of the Council of Trent and the validity of lay baptism was as natural and eager as that of racquets or cricket. With one of them Edward formed a secret, doctrinally conservative Society for Holy Living, ‘to bring the kingdom of God to the poor, to promote the spiritual unity of the Church and to practise the precepts of the Sermon on the Mount’. His emanations of sanctity once provoked a less pious schoolfellow to ask him, ‘And how is the Bensonian Ethereality?’ and earn in response a forgiving smile. ‘I don’t care for the book, nor for the people who write such things,’ remarked his mother on finding him engrossed in Tract 90 of John Henry Newman’s Tracts for the Times, suggesting the possibility of a leaning towards Catholicism that rocked her Unitarian soul, ‘but I don’t want to stop you reading what you wish: only you ought to think, would your father have approved of it?’

‘Yes, mother, I have thought of that and I think he would wish me to be acquainted with what is going on in the Church,’ was the young man’s crushing reply.

Edward had a clear fondness for ceremony and ritual. He converted an office in his father’s deserted lead factory into a private oratory, with brass rubbings from nearby churches, a cloth-draped table for an altar, stools to kneel on, and a cross made for him by an old carpenter (who earned rebuke for his pains, as he had rounded off the edges instead of leaving them square). Here he went every day to say the Canonical Hours. Suspecting that while he was at school his sisters were disobeying his injunction on their entering the room, Edward booby-trapped the door, bringing a battering shower of books down on the head of his little sister Emmeline when she peeked in one morning. She did not merit the forgiving smile. It was, after all, his oratory.

Though straitened in circumstances Edward Benson was not bereft of achievement. Cambridge beckoned. In 1848 he proceeded from King Edward’s School to Trinity College as a subsizar (partially financially supported by the college), then followed a steadily rising path, becoming a full sizar the following year, and finally a scholar (an honour that brought more substantial support). His sister Eleanor wrote to congratulate him: ‘What a fine, clever fellow you are, you will soon be Archbishop of Canterbury, and would deserve to be, should you not?’, a question Edward surely deemed rhetorical.

Edward lived with ferocious frugality, surviving his first year at university on expenditure of just over £90, less than the earnings of a lowly clerk. (Mr Guppy, in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House, published in monthly parts from 1852, is comically proud of an annual income of £104, set to rise to £117.) Edward took in pupils to support his finances, one summer acting as tutor to two boys at Abergeldie Castle, on the River Dee near Aberdeen, and catching sight at the Invercauld Highland Games of a young Queen Victoria (the most plainly dressed woman there, he thought) and Prince Albert (‘horribly padded and belted’). His mother let go her domestic staff, and did all the cooking, scrubbing, ironing and cleaning herself, with the help of Edward’s sisters, but when she wrote to him suggesting that she make use of her late husband’s cobalt patent, and set up in business, Edward was horrified. A mother in ‘trade’ was utterly unacceptable. The rigid strata of society might be beginning to bend, ever so slightly, as all manner of people rubbed shoulders (and made fortunes) in newly industrialized cities and every example of humanity piled into railway trains to speed around the countryside, but the direction of any social mobility should be upwards, not down. A mother who scrubbed her own floors was bad enough, but concealable; one in trade – especially for someone in such an environment as the University of Cambridge, and particularly when it came to career or marriage prospects – was too dreadful to contemplate. Edward would not admit such a stumbling block to his progress. ‘I do hope and trust you will keep out of it,’ he instructed her. ‘It will do me so much harm here, and my sisters so much harm for ever! I trust that the scheme be abandoned once and for all.’ Mother complied. She always did.

Instead, Harriet Benson scraped together what she could of her capital and invested it in the railways. The ‘roaring and rattling railroad days’ had begun, with (as Charles Dickens put it) ‘wheezin’, creakin’, gaspin’, puffin’, bustin’ monsters’ shooting around the country at up to 36 miles per hour. (‘Not quite so fast next time, Mr Conductor, if you please,’ said Prince Albert as he alighted after his first train journey in 1842.) Between December 1844 and January 1849 the network grew from 2,240 to 5,447 miles. In 1849, 60 million journeys were taken by train. Shares in railway companies promised unimaginable riches, and thousands of people joined in a frenzy of speculation that became known as railway mania. Harriet Benson can hardly be blamed for secretly becoming one of them. Just months after she did so, the market crashed, with an estimated loss to investors of some £800,000,000. Mrs Benson was ruined.

A few months later, all her offspring in Birmingham fell ill with typhus fever. Not only did Harriet Benson have single-handedly to nurse six children who were tossing and sweating in delirium, but she had to keep the household running without their help. For a while she withheld the seriousness of the situation from Edward, as she did not want to interrupt his work at Cambridge or upset him, but eventually she had anxiously to write for help. ‘Do you think,’ came the reply, ‘it could be managed that instead of my coming down to you, you yourself should come up here for a week and bring one of those who are under ten years old – (that would be half fare by the Railway). This place is so beautiful and fresh now, that I think it would restore the health of the most confirmed invalids.’ The house in Birmingham must have been seething with infection. Edward’s own health and well-being, all (not least the Good Lord himself) would surely agree, eclipsed that of the rest of the family. In case this part of the letter was too complicated, he trusted his mother would ‘not grudge the trouble of reading it over again’, and he went on: ‘prayers for your restoration in my heart, mingled with prayers that He will not suffer me so to abuse the health and happiness and prosperity that He gives me here (for in all these, my dear Mother, I know that you rejoice). . . ’

Two days later Edward wrote again, wishing he could say something to comfort the invalids, but assuring them that they would comfort each other best – and reminding them that the ‘true comfort is of the Comforter’. He was halfway through a third letter when news arrived that his sister, Harriet, had died. She was eighteen. Edward’s letter changed course to become a paean to her grace, truthfulness, obedience and saintliness. Finally, he set off for Birmingham.

Mrs Benson herself laid out the wasted body of her eldest daughter and namesake, then retired to bed. At midnight, she got up, lit a lamp and went in for one last look at the body. Back in her own bedroom, exhausted, she lay down with her head on her hand to sleep. She died in the night of heart failure. By the time Edward Benson arrived, he had two funerals to arrange.

Edward’s mother’s annuity and the right of the family to occupy the house in Birmingham terminated with her death. Her railway shares were worthless. Once expenses had been paid, Edward calculated that the entire family fortune amounted to just over £100. Aunts and uncles rallied round. A Benson half-uncle sent Edward money to meet immediate needs; seventeen-year-old Eleanor and ten-year-old Ada were taken to Bristol to be looked after by Mrs Sidgwick, the widow of their father’s cousin, and the rest went – temporarily – to stay with Uncle Thomas Baker, their mother’s Unitarian brother.

A rich and generous businessman, Uncle Thomas wrote to Edward offering to take the baby of the family – little Charlie, who was eight – and maybe one of the sisters, and bring them up as his own. He undertook not to ‘instil into the child any Unitarian principle’, to bring him up according to Edward’s religious convictions and to allow Edward ‘freely [to] exercise [his] influence by visit or by letter, and hereafter decide on the boy’s school’. Edward rejected the offer. He would not permit even the faintest whiff of Unitarianism to taint the air his brother breathed. Better that Charlie live in penury and be poorly educated than imperilled by comforts and ministrations offered by such inappropriate substitute parents as Aunt and Uncle Baker.

AN INCIDENT IN WHICH EDWARD BENSON, UNDERGRADUATE OF TRINITY, STANDS BY HIS HIGH PRINCIPLES

A story told of the African American pastor and abolitionist Alexander Crummel, by the Revd J. Bowman of New Southgate, who was present

On a certain Degree day in 1850 or thereabouts the undergraduate Crummel of Queens’ appeared in the Senate House to take his degree. A boisterous individual in the gallery called out: ‘Three Groans for the Queens’ nigger.’ A pale, slim undergraduate in the front of the gallery, very youthful-looking, became scarlet with indignation and shouted in a voice that re-echoed through the building: ‘Shame, shame! Three groans for you sir!’ And then: ‘Three cheers for Mr Crummel!’ This hurrah was taken up in all directions, and the original offender had to stoop to hide himself from the storm of groans and hisses that broke out all round him. That pale undergraduate was one Benson, later Archbishop of Canterbury.

Thomas Baker knew how to deal with his objectionable young nephew. He wrote that he had hoped Edward’s ‘own good sense’ would have preserved him from ‘such narrow and debasing sentiments’. He withdrew all support, adding: ‘I do not see how you can expect from us any sympathy in pursuing an education which has so far taught you not to regard us as friends, but as a class whose influence, beyond a very small range, is to be avoided.’ If that was the way Edward felt, he would ‘hereafter be bound to provide for [Charlie’s] future as he would have been provided for had he been with me’.

Edward flinched a little. His beliefs were, after all, deeply and sincerely held. He noted his uncle’s ‘uncommon candour’, thanked him for his kindness, and asked his pardon. Then he went on to lecture the older man on Christian doctrine and practice, holding up his own religious principle as ‘not a thing of tender feelings, warm comforting notions, unpruned prejudices, and lightly considered opinions’ but one that ‘consists of full and perfect convictions, absolute belief, rules which regulate my life. . . and tests by which I believe myself bound to try every question, the greatest and the least.’ He rounded off his sally with: ‘This is a very serious matter; and I hope you will not think bitterly either of the young man’s presumption, or the young Churchman’s bigotry. Bigot (so-called) thus far, a conscientious Catholic [here meaning orthodox Anglican] must ever be.’

Buffeted between beliefs about which he probably had no inkling, little Charlie Benson was blown on to the cold hard land of brother Edward’s ‘full and perfect conviction’. This might have spelt disaster for the boy, had it not been for the intervention of the kindly Mr Martin.

Francis Martin, the Bursar of Trinity College, was well into middle age, gruff, grey-haired, solitary, unmarried and rich. He was also a fervent Evangelical. Soon after Edward returned to Cambridge from Birmingham, Mr Martin noticed the beautiful, troubled young man making his desultory way across the Great Court. He knew of the family bereavements, offered his condolences, and invited Edward up to his rooms. The visit marked the beginning of an intense and passionate protectorship.

A fierce figure, with high collars that scraped and rasped at his cheeks, pale grey eyes, parchment-like skin, a rough manner and a resonant voice, Mr Martin commanded Edward’s deference, but treated him with a parental tenderness that grew into adoration. The crusty old don softened, and began to make his affection tangible. He offered to pay all Edward’s expenses at Cambridge and to continue as long as the money was needed; he furnished Edward’s rooms, supplied him with cheques to cover other needs, marked his own birthday by making over £100 as a gift to Charlie and the young ones, rescuing Charlie from the poverty into which his brother’s strong conviction would have cast him. Mr Martin even set aside £500 for the Benson girls’ dowries.

Edward’s sister Eleanor observed that her brother had a disposition to ‘make idols’, particularly of older men. At school he had formed an ‘almost romantic attachment’ to his headmaster, James Prince Lee, and at his first sight of the Tutor of Trinity, William Collings Mathison, in chapel, he had been awestruck, thinking he should never be able to approach such a quietly elegant, attractive man, with his ‘small intelligent forehead and blue eyes and placid brow’. Yet the intensity of Mr Martin’s feeling was confusing. ‘I do not worthily return his affection,’ Edward wrote. ‘I find myself hardly able to understand it.’ Nevertheless, he blossomed under the older man’s care. The prig who could write such an uncompromising letter to his uncle could also be high-spirited and fancy free; he could be mad with the joy of a summer’s morning, and take his mind off on crazy new adventures. Swept along by a fervour for the supernatural that spread countrywide in the 1850s, and echoing his father’s and Dr Sollitt’s interest in the occult, Edward helped found a Ghost Society, to collect and investigate ghostly tales. He wrote poems, took pleasure tours with Mr Martin and enjoyed silly jokes. In the 1851 long vacation he joined a reading party led by William Collings Mathison in the Lake District and went on long walks, enthusing in his diary that he ‘shrieked and shrieked with delight’ as he plunged into the Mirror Pool at Rydal Head, climbed up Scardale Fell then scampered down to Windermere, ‘jumpy, jerky, wally-shally, boggy-joggy, splashy rushy, thumpy, zany, coky boasty, bathy, warmy, coolly, freshy’.

LINES WRITTEN BY EWB FOR HIS FRIEND MR FRANCIS MARTIN, ON SEEING HERONS AT GRASMERE

One floating o’er the gorge, and one

Down dropping o’er the scar,

And one, wide-oaring o’er the wood

The Herons come from far,

From lonely glens where they had plied

All day their feasts and war.

Ah, goodly lords of a goodly land,

How calm they fold the wing:

How lordly beak on bosom couch’d

To their pine-hung eyrie swing,

And stand to see the sun go down

Each like a lonely king.

Mr Martin joined the party at Grasmere. Having twisted an ankle jumping off a coach, Edward sat quietly on a bank beside the lake, watching herons in the sunset and writing a poem about them for his patron and friend. That night he read Mr Martin his poem and received warm praise. The old man read aloud from Terence, Milton and Shakespeare. Edward noted in his diary ‘how most pleasant’ it was to see Mr Martin, ‘with his short cut grizzled hair, and bright face with its constant smile, patting the book and stroking it, and sometimes smiling more and sometimes less, and now and then looking upwards with a scarcely heard Beautiful Beautiful – what can be more beautiful. . . leaving off to stroke your hand or lay his hand on your shoulders and play with your hair.’

It was this sentimental, headstrong, self-regarding, absolute, and conscientiously Christian young man for whom Francis Martin had packed his carpet-bag and hastened across the country with news of a first-class degree and the Senior Medal, and whom little Minnie Sidgwick had so aroused with her cleverness and her reading of The Princess.

CHAPTER THREE

Mrs Sidgwick was startled by Edwards disclosure, and unsettled by his intentions. Little Minnie was a year below the age of consent and, even so, that was quite young enough. Mrs Sidgwick did not think it proper that a girl should marry before she was twenty-one. She could not entertain the idea of an engagement until, say, eighteen. Seven years away! Who was to say that the boy would not change his mind? Eleanor observed that Edward made idols. Was this not just one? And there were yet so many duties and accomplishments for Minnie to acquire! Besides, there was the childs health to consider. She would soon be passing from girlhood into womanhood, a time that demanded the most anxious maternal supervision if a girl was to emerge unscathed. This was just the moment that any inherent weakness, mental or bodily, might show itself. Minnie was not very strong just now. She was fragile, an unformed child. Certainly, nothing must be said to her for the present. Edward had barely left the house when Mrs Sidgwick picked up her pen to write to him.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!