5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

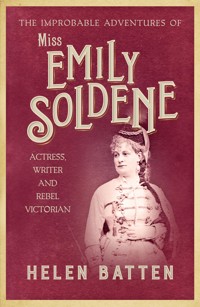

'A vivid tale of a woman born for the stage, stardom and scandal' - Holly Kyte, author of Roaring Girls: The Forgotten Feminists of British History 'One of the most irrepressible women I've come across'- Jane Robinson, author of Ladies Can't Climb Ladders 'I rode on the stage in such style, that the men in front forgot I was a girl, and also forgot to laugh.' From humble beginnings with the threat of the workhouse looming, Emily Soldene rose to become a star of the London stage and a formidable impresario with her own opera company. The darling of theatreland, she later reinvented herself as a journalist and writer who scandalised the country with her outrageous memoir. Weaving through the grit and glamour of Victorian music halls and theatres, taking encounters with the Pre-Raphaelites and Charles Dickens in her stride, Emily became the toast of New York and ventured far off the beaten track to tour Australia and New Zealand. Batten paints a vibrant portrait of an almost forgotten star who trod the boards, travelled the globe and tore up the Victorian rule book.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 414

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

The Improbable Adventures of Miss Emily Soldene

Actress, Writer and Rebel Victorian

HELEN BATTEN

To Amber, Scarlett and Daisy

Contents

Emily as King Chilpéric in Hervé’s operetta Chilpéric

Introduction

Every family has their own myths and legends: the tales of supposedly famous and infamous ancestors, passed down through the generations to bring out at the annual gatherings of the tribe, the weddings and the funerals; to intrigue grandchildren or amuse new partners.

Among our forebears we allegedly had a notorious actress. According to my nanna she was grand and slightly risqué – her name was Lady de Vries. Other than that she knew no more; just that she was grand.

‘What? A real lady?’ I asked her.

‘No dear, not a lady, not a real lady at all I imagine,’ she said.

Rather prescient of Nanna as it turned out.

At the time there was no evidence for the existence of this Lady de Vries, and we had no idea how we were supposed to be related to her. She was dismissed by the family as another example of my nanna’s dramatic imagination.

However, years after Nanna had passed away and the theatrical lady had slipped from the family memory, I happened across her while doing a piece of research into our family history. I had been asked to write a book about a more contemporary set of female ancestors. I made a phone call to a local historian of the ancestral village in Hertfordshire. He told me that I had a famous actress in the family, that I should talk to a renowned historian of musical theatre who lived in New Zealand. He gave me Kurt Gänzl’s address. There followed a flurry of emails, and two monumental volumes of a thousand words each, kindly given by Kurt (because I’m family), which were sent halfway across the world and landed on my desk.

It seems we did indeed have a theatrical ancestor. In fact, she was my first cousin three times removed; my great-great-grandfather was her favourite uncle. She was a singer as well as an actress and she had several names (none of them de Vries), but the one she used most was Miss Emily Soldene.

With one Google click I found a photograph. Emily Soldene, singer, born in the year after Victoria became queen and dying just two years before the beginning of the First World War – a woman who had truly lived through an entire era. She was dressed in curious silk boy-britches, a low-cut kimono-style jacket revealing a fulsome bosom and thigh, a floppy pastry cook’s cap slipping off a tumble of blonde ringlets, and a face tipped heavenwards, eyes hopeful, expectant; her mouth wide in a secret smile as if communicating with a celestial friend in the firmament. Cheeky and yes, probably no lady, at all.

But what I read next really caught my attention. Not only had Emily been a star of the music halls, moving up in society to become the leading lady in light operas, but she had also started to produce and direct the productions she starred in. Then she had set up her own theatrical company. She had bought the tenancies of London theatres like the Lyceum and the rights to popular operas. Emily had even brought Carmen to the British provinces for the first time (with herself in the role of Carmen of course).

And there was more – like today, if you really wanted to make it big you had to go to America. Emily took her productions to Broadway, then across the Wild West to a gold-booming San Francisco and back again several times. And then she couldn’t resist hopping on a boat and going across to Australia and New Zealand. These trips were long, dangerous and expensive; only a few very wealthy, adventurous ladies or actresses would have made them. These trips were Emily’s biggest triumphs and her biggest disasters.

But perhaps the most surprising development in Emily’s full life was her second career as a journalist. In an era when the lady journalist was a new and distrusted phenomenon, at the age of fifty-two, Emily managed to get herself a weekly column and a byline in one of Australia’s largest newspapers, the Sydney Evening News, sending dispatches from London on anything that took her fancy. Emily had that most rare of things for a woman from a working-class background – a public voice.

There was also an understudy to Emily’s main role. A few more Google clicks revealed the existence of another doublet-clad ancestor, dressed in velvet knickerbockers, pantomime tights and high heels. Emily’s sister, Clara Vesey, joined Emily on the stage when she was twenty years old. There is less written about Clara, although plenty of photographs – she was one of the most photographed actresses of the nineteenth century. Eleven years younger than her half-sister, Clara was rarely allowed to play lead roles – these were reserved for Emily, despite the fact that Clara was supposedly an excellent singer (and was definitely considered prettier). It seems Clara was destined to travel with her big sister’s company as Emily’s understudy.

At first glance it seems Emily was the main player and Clara tagged along in her slipstream, a passenger on board for the often-bumpy ride – but the story is more complicated. Sisters can be the best of friends and the biggest of rivals. Eventually Emily and Clara made different life choices, but these choices and their consequences seem to say something not just about the sisters themselves, but also about women in nineteenth-century society in general, and perhaps even women today.

Emily has faded from the limelight now, but in Victorian Britain she was a star, and together with Clara, the sisters were regular celebrities, invited to parties for their wit, gossip and general bonhomie. The people they called friends included Pre-Raphaelites, peers of the realm, maharajahs, Rothschilds, Dickens, Gladstone, Oscar Wilde and the Prince of Wales. They did the Season with impunity, drank champagne, ate oysters and gambled on horses, somehow working exhaustive social lives around their theatrical commitments. They had close friendships they shouldn’t have had, with grand men. Emily claimed to have been stalked by Jack the Ripper. I know this because Emily also wrote a book, My Theatrical and Musical Recollections. It was one of the bestselling books of 1898 and scandalised society. As one reviewer said:

She has had the good fortune to know many of those whom the world calls smart people, and many of those whom the world calls smart people have had the evil fortune of meeting her. One and all these she ‘gives away’.

It’s a great read. Emily has an icy wit and a literary twinkle in her eye, with plenty of mischief and just a sprinkling of spite for her few bêtes noires.

But one of the secrets of Emily’s success was her awareness of the Soldene brand – and the memoir, fun as it is, doesn’t tell the whole story. In fact, like too many autobiographies, truth has been sacrificed at the altar of image. The real-life adventures of Miss Emily Soldene are darker, and actually more heroic. I think she left some of the best bits out.

So I’ve put them back in.

Emily on her great American tour as the pastry cook, Drogan, in Geneviève de Brabant

Chapter One

BROADWAY

Stage fright (noun): Nervousness on facing audience especially for first time (Oxford Dictionary)

On the same night Emily Soldene made her debut on New York’s Broadway, news of the death of her little sister, Clara, had been telegraphed back to England.

As it turned out this telegraph was slightly premature, although as Emily left her and Clara’s suite at the Fifth Avenue Hotel for the theatre on a dismal night in November 1874, she was taken aside by doctors and warned that this was probably the last time she would see her sister alive.

This was difficult for Emily, not least because she always suffered from nerves before she went on stage, and today the stakes were particularly daunting. She was about to perform the lead role in a new opera to a theatre full of critics she knew were waiting for the much-hyped English upstart to fail. Of course, the one person who always managed to calm Emily was her sister, Clara; but now that Emily really needed her, Clara was not by her side. Although it probably occurred to Emily that Clara could have said the same thing.

Emily was a great believer in omens, and from the start there were signs that this trip was going to be difficult. As the White Star ship, the Celtic, sailed out of Liverpool on a sunny autumn morning, Emily’s business partner and mentor, Charles Morton, discovered that he had left his umbrella behind. Everyone had laughed and teased him about what a bad portent this was. Less than forty-eight hours later no one was laughing:

‘What horrors! what suffering!’ Ah! if the ship would only be still for five minutes! Neither the ship nor anything else would be quiet for five minutes. All the company were prostrate, and my sister Clara soon dangerously so. The wind for days blew and howled … Every now and then the ship took a header, then sprang up with a sickening bound, skimmed the tops of the waves like a swallow, shook, shivered, vibrated, and, shaking the water from her shining sides, down she went again. In a moment of confidence a gentleman kindly informed me she would certainly “break her back one of these days”’

The stormy seas were relentless for eleven days. When they finally arrived in New York Harbour it was clear that every member of the cast was severely depleted, exhausted and weak. But the worst was Clara. Always fragile, now she looked hollowed out and frighteningly pale. Her blue eyes seemed bigger as her face got smaller, like a tiny and frightened woodland creature with bones that could snap. Clara had to be carried onshore, and then instead of getting better, she got worse and developed what Emily described as ‘gastric fever’. She became low and tearful; Emily couldn’t remember the last time she had seen her sister smile, and the worst thing was Clara’s terrible insomnia. The doctors tried everything, but the more sleeping draughts she took, the less she slept: ‘there she lay, always wide-awake.’

At first Emily worried that Clara might not be well enough for the opening night. Clara was supposed to be playing the impudent servant boy Oswald. Her costume had been specially designed to please the largely male audience, with provocative tights, a doublet short enough to expose nearly all of her legs, a short cape and feathered cap styled to sit at a cheeky angle on her mass of curls. Emily never underestimated the need to captivate, some might say titillate, the erotic imaginations of their gentleman fans. Without Clara on stage, Emily was missing one of her greatest assets. But this worry was soon eclipsed by the greater fear that Clara would never take to the stage again. All the doctors that Emily had summoned to the Fifth Avenue Hotel had given the same prognosis – that if Clara didn’t manage to get some sleep soon, her body would give up and she would die of exhaustion and starvation. Of course, sleeping pills had yet to be invented.

A primary cause of insomnia is fear, particularly when the nervous system is triggered into fight or flight mode. If this happens, it’s difficult to fall asleep, and you wake at the slightest disturbance. Something about the voyage must have put Clara into a state of terror that could not be turned off or reassured, even now that they were on dry land. This had been Clara and Emily’s first ocean voyage. They had only ever been to sea once before, and that was a day trip with a group of young parliamentarians who had taken them out from Portsmouth across to the Isle of Wight. The trip nearly ended in disaster when on their way back they were surrounded by deep fog and found themselves in the path of an ocean liner. They were only saved by a young politician shouting, ‘Shove her along like h—l!’ When Emily now stroked her sister’s forehead and kissed her hand, it was terror that she saw in Clara’s eyes.

As Emily was helped into her costume by her trusted wardrobe lady, Mrs Quinton, she must have wondered what on earth she had done – gambling not only her finances and reputation, but the very life of her sister. And she might have wondered whether she should go back to the hotel and stay with Clara, she might have considered that no performance could ever be more important than the life of the person she was closest to in the world. She was probably facing the most dreadful dilemma.

In the end Emily must have decided that the show had to go on, because suddenly she was standing backstage waiting for her cue. Luckily, she was playing one of her favourite roles – Drogan, the pastry cook, in Offenbach’s Geneviève de Brabant. It was the role that had settled Emily’s fame, and had run for an unprecedented three hundred shows in London the year before. It had been met with thrilled appreciation from the capital’s opéra bouffe fans. Unfortunately, Geneviève de Brabant had already premiered in New York and proved less than popular. Emily believed this was because it was performed in the original French without any cultural adjustments. However, she knew from others’ experiences that what was popular in Britain didn’t always translate to the States, and she had also been set up for a fall.

Emily’s promoters were an ambitious couple of young men called Maurice Grau and Carlo Chizzola, who had just started out and decided to specialise in opéra bouffe. They had taken the lease of the old French Theatre in Fourteenth Street, renamed it the Lyceum, and hired Emily and her Soldene Opera Bouffe Company to be their star offering for the Christmas season. As well as planning the tours and negotiating the venues and ticket prices, the promoter’s job was to handle the publicity. In this, Chizzola and Grau had surpassed themselves, blitzing the city and the press with the following notice:

Messers Maurice Grau and Chizzola experience much pleasure in being able to introduce to the New York public Miss Emily Soldene the reigning Queen of the London Stage whose lyric and dramatic talents have raised her to an enviable position and rendered her a universal favourite with the public …

The novel entertainment known as English Opera Bouffe must not be regarded in the light of a mere imitation of the French, but rather as a clever adaptation which, without losing the lightsome grace and champagne sparkle of the original, fashions the dialogue and its scintillating wit to the taste and humour of English speaking audiences.

Miss Soldene has labored successfully to assemble around her a company of marked ability in which will be found the same harmony of action and perfection, of ensemble characterizing the troupes of leading comedy theatres.

The bar had been set high for the Soldene Opera Bouffe Company, not least because they were facing an American press that had already made up its mind about British theatrical imports. Lydia Thompson and her ‘British Burlesque Blondes’ had arrived on American shores in 1868, performing a set of burlesque musical numbers. In the nineteenth century burlesque had not yet evolved into the erotic dancing that we know today. The word burlesque originally meant to make fun of, and Victorian burlesque consisted of women playing male roles in tights. The shows were full of jokes and the British Blondes were expert at improvising witty repartee with the male audience. They were as scandalous as they were popular. Thompson was the darling of the New York newspapers, but outside the city the press were more conservative and she faced disgust wherever she went. However, Thompson revelled in the publicity. During a run in Chicago, the owner of the Chicago Times, Wilbur F. Storey, attacked her so ferociously that she made her troupe post notices calling Storey ‘a liar and a coward’. Then Thompson and her husband horsewhipped Storey at gunpoint. Thompson told a reporter that Storey ‘had called her by the most odious epithet that could be applied to a woman’ and she could stand it no longer. Despite being fined and jailed, Thompson said she was glad she did it. Sales of tickets soared and Thompson made $370,000 – the equivalent of nearly $7 million today.

However, by the time Emily arrived six years later, the novelty of the British Burlesque Blondes had worn off, and the press were lamenting the arrival of yet another indecent British import – which was unfair because, although a Soldene production always contained a splash of sauciness, it was a much more subtle, classy offering, with more talent on stage. Emily was producing an opera with integrity.

This view from the press was not helping Emily’s state of mind. In common with some of the greatest performers in history, Emily suffered from nerves. Stage fright causes the blood vessels in the extremities to constrict. The performer’s body reacts like an animal under threat. As normal digestion closes down, there is a feeling of butterflies in the stomach and the body instinctively tries to assume a foetal position, which is unhelpful if you are about to go on stage. The definition of courage is not an absence of fear, but feeling the fear and doing it anyway, and by this measure Emily had a lot of courage. Because, despite feeling sick with dread and having no voice to speak of, Emily walked out of the wings on the night of 2nd November, into the bright, blinding lights to confront a full theatre of not entirely friendly faces.

As Emily opened her mouth to sing the first note, nothing came out. Her voice was barely a croaky whisper. But as so often happened, from somewhere came some sort of sound, and once she could hear herself, in a kind of torturous virtuous circle, she seemed to be able to make more noise, and the louder it got, the more she seemed able to relax and slip into a familiar groove. Her spirits and her notes started to soar, and she may even have started to enjoy herself, although it must have been a difficult moment when Oswald the page came on stage and she remembered Clara lying on her deathbed in the Fifth Avenue Hotel. The cast, despite being weakened by the journey and dreadfully nervy, followed their leading lady and began to recapture a bit of the sparkle that had so thrilled the London audiences a few months before.

The performance came to an end, and the applause was enthusiastic but not overwhelming. Emily knew how important it was to leave everyone with the impression of a hit and so she harnessed a trick she had picked up over the years. She had learnt to bow in 1866 from a leading lady called Madame Sherrington:

A charming artiste, but artificial and perfect to faddish in deportment. From her, by close observation, I acquired the effective stage curtsey. When you find your audience flabby and not inclined to rise to the occasion, this is how you manage them. You finish your aria, you bow slightly. They, rather bored, applaud slightly, you bow somewhat deprecatingly right and left, then a little lower full front. They applaud more, you repeat the manoeuvre, but show no signs of going off. They applaud rather vigorously, you convey by gesture how utterly unworthy you are of so much distinction. They appreciate such delicacy of feeling, and applaud vociferously, loudly, continuously, rapturously. Now is your time to retire, you bow and bow, and, always keeping your face to the audience, slowly exit, kissing your hands and overcome. Thunders of applause and acclamations – ‘Brava, ‘Brava,’ ‘Bravissima,’ ‘Bis,’ ‘Bis.’ Of course you take your call and your encore, you have earned it.

That night Emily earnt her standing ovation. It was not perhaps her longest or loudest, but it was an ovation of some kind. A good sign, but she would have to wait until the morning and the press reviews to find out whether she had a hit. But first Emily faced an even more daunting prospect – going back to the hotel and seeing whether Clara was still alive.

She opened the door to their room to find the maid laying out a supper for her:

‘My sister?’

She nodded. ‘Resting ma’am. But not asleep.’

Emily was overcome first with relief and then a feeling of almost terminal exhaustion from the day’s events. She couldn’t go in to see Clara, not yet. She sank into a chair and forced herself to eat a little supper. In the quiet, by the light of the fire and flickering candlelight, Emily read a book – probably a novel; it may even have been Dickens, as he was a favourite. She waited until her body and mind had quietened a little. Then she crept into the bedroom to find Clara, awake, of course, and just as pale. Emily lay down on the bed they shared:

Taking her in my arms, I held her close and petted her and patted her like a baby, and 'hushed' her, and prayed in my heart, as I had never prayed before, that she might sleep. And after a bit she dozed for five minutes, then woke up wondering, ‘where was she?’‘Hush,’ said I, sharply, ‘Go to sleep,’ and she did; slept for six hours. When she awoke I was exhausted, stiff, cramped, all the strength had gone out of me, I could not move, but she was saved.

From that moment Clara got better. It took a few weeks until she could emerge, but when she did, she looked ‘lean and rather like a young stork’, but she had survived.

Occasionally in the press Clara was referred to as Emily’s daughter. Although there were many interesting grey areas in matters of marriage and parentage in the Soldene family tree, it seems unlikely. Clara’s birth certificate states her year of birth as 1849. Emily’s birth certificate has yet to be found. It took historian Kurt Gänzl twenty years just to find the first official mention of her. In the 1841 census she is two years old, called Emily Lambert, and is living with her mother Priscilla and a man she is recorded as being married to; a clerk named Frederick Lambert. In other official documents the given date of her birth varies slightly, but not by much. Gänzl has settled for her date of birth as 30th September 1838. This means Emily would have to have been an eleven-year-old mother. Not impossible, but still, rather implausible. Siblings, particularly sisters, can be attached to each other in such a way that the older sibling becomes the mother figure, particularly in families where the mother is otherwise engaged; and the strongest attachment comes when they both realise that they must band together against the parents. There were plenty of good reasons for Emily and Clara to be close.

When the notices came out the next day they were broadly favourable, with plenty of admiration for the leading lady herself. This is the one, from The Play, Emily picked out to put in her memoir:

The brightest anticipations in respect of the immediate and marked success of the Soldene English Opera Bouffe Company have been realised. Miss Soldene and her artists have won a victory of which the results are destined to be enduring … So rare a grouping of excellences in one entertainment is seldom, if ever, brought about, and as a consequence, the immediate decision of the French ‘nerve’ of the acting, the charm and beauty of the singing, and the magnificence of the stage costume, was of the most favourable kind.

Of course, Emily omitted from her memoir the less ecstatic reviews which show that her attack of nerves had not gone unnoticed, such as this from The Clipper:

She had sung but a few notes and spoken a word or two, before a feeling of disappointment spread, as her voice was almost inaudible both in song and speech. As she warmed up to her work, however, she improved considerably and the fact was soon realized that the new star of the burlesque hemisphere was not only a refined and cultivated artist in acting, and one very graceful in action, but also that she possessed a voice of marked sweetness and purity in tone, though ordinarily of much power.

It seemed as if Clara had survived and so (narrowly) had Emily’s Broadway adventure, but it had been a huge gamble. What had led Emily to risk launching herself on a Broadway stage in the first place or indeed to become an actress at all? For an answer, the first place to look might be to her mother, Priscilla Swain.

Emily’s grandmother’s pub, The Horse and Groom, in Preston, Hertfordshire, where she spent much of her childhood

Chapter Two

THE BIGAMIST BONNET MAKER

Such a fuss about two wives, when lots of people have three or four and nobody says ‘nuffin’! How do I know? Oh well – because – well, I just know, don’t you know (Emily, 1903)

Emily’s mother, Priscilla Swain, was unconventional, but then she came from an interesting family.

Priscilla’s grandfather, Stephen, was a person of renown in the town of Hitchin in Hertfordshire, not least because he had a wooden leg, which he had acquired after fighting the French in Canada. He was in the 19th Dragoons, and came back from the Americas with some choice military songs which were passed down the generations; my mother remembers her grandfather singing them. Stephen obviously had a talent for leadership (or at the very least liked being in charge) because at various times, as well as running a shop on Hitchin’s high street, he was a special constable, surveyor of the highways, receiver of the assize returns and the master of Hitchin’s workhouse. Perhaps Emily and Clara had inherited their love of theatrical clothes from him – he put the purchase of some plush new crimson velvet breeches on expenses, after his pair was stolen by an inmate of the workhouse.

When Stephen’s son, Priscilla’s father Charles, got into trouble for making a young lady pregnant and refusing to marry her (he was taken to court and ordered to pay maintenance), Stephen knew just what to do with him. Charles was sent off to join the 19th Dragoons and once again an ancestor found themselves fighting through a freezing Canadian winter, although this time he was battling the Americans and he didn’t lose a leg. On the way the dragoons stopped in Ireland and it was here that Charles finally did get married, not to an Irish woman, but to a local Hertfordshire girl, Catherine (Katie) Young, who sailed all the way across the Irish Sea in 1811 to get wed. Charles must have been quite compelling. Nine months later Katie was back in Hertfordshire and gave birth to Priscilla.

It was five years before Katie saw Charles again. Was this a blessing or curse? At first glance it seems that it must have been very hard for Katie, essentially a single mother, with no idea when, or if, this compelling new husband was ever going to come home. He didn’t have a track record for constancy and his father hadn’t set a reassuring example of coming back unharmed.

However, Charles’s presence may not have made things much easier. The family tree reveals that when Charles did return in 1817, Katie had nine more children over the next twelve years – all but one of whom survived into adulthood. In fact, Katie only stopped having children when Charles died, presumably because he was an alcoholic, because by this time he ran an alehouse in a small village outside Hitchin called Preston, and the cause of death on the certificate is liver failure. It’s not known why Priscilla decided to leave the security of her Hertfordshire village and run away to London, but things might have been a bit fraught in the Swain household. It could also be that Priscilla was quite ambitious. What is known is that at some point in the early 1830s, whilst still a teenager, Priscilla decided to walk out of her village inn home and take the road south down to London. She made it as far as Clerkenwell and then stopped.

This was an intrepid move – nineteenth-century London was not for the faint-hearted. The American novelist Henry James called it a dreadfully delightful city, ‘the biggest aggregation of human life, the most complete compendium in the world.’ It was a gathering of fortune seekers and chancers, buying and selling in its narrow, dark streets, full of filth, literal and metaphorical. According to the philanthropist Charles Booth, three-quarters of the population lived in poverty and it was poverty on a scale that is difficult to imagine today. Not even in our most deprived, hidden corners do people now live in the conditions that most did in Victorian London. It was normal for a large family to live in one small room with cracked or paneless windows, sleep on lice-infested mattresses or straw on the floor, use pots as toilets, and be surrounded by vermin and cockroaches, and smoke from a fire, if they were lucky enough to buy a piece of coal. There was no welfare state, no sanitation, no healthcare, no education, no protection from unscrupulous landlords or employers. Even if you were managing to live above subsistence level, the precariousness of life meant that you could lose what little you had very quickly. The threat of the workhouse must have felt very real.

This meant that nineteenth-century London was edgy. People lived unconventional lives with chaotic domestic arrangements that country-bred Priscilla would never have encountered before. One can only imagine what effect the sights, sounds and smells must have had on our nineteenth-century Dick Whittington. The closest thing she’d experienced to a metropolis was the market town of Hitchin.

But Priscilla must have known that London offered more opportunities than anywhere else in the world, and Priscilla had a highly marketable skill – she was a bonnet maker. Millinery was one of the few occupations open to an upper-working-class lady. It was a relatively respectable profession requiring a four- to five-year apprenticeship, technical skill and some creativity and fashion sense. Hundreds of women in Hertfordshire and Northamptonshire made a relatively good living from it and the Swains were no exception. Millinery was a tradition passed down the female line – the last person in my branch of the family to make hats for a living was my great-aunt Alice in the 1920s. Most women worked from home and sent the hats down to London, but Priscilla must have sensed the greater opportunity just forty miles down the road. London was the greatest clothing and accessory manufacturing centre in the world, full of small self-employed enterprises. It was the one place where it would be relatively easy for Priscilla to start her own business.

At first she rented a room in Clerkenwell, but Priscilla must have prospered because by 1841 she is recorded in the London Trades Directory under the name of Mrs Priscilla Lambert, renting a warehouse down the road in Aldersgate and owning a hat shop. This means that before she was even thirty years old she was running her own business in the heart of the capital. Her premises were in a busy street which has now been replaced by the Barbican. It was not the most exclusive shopping street in London, but it was arguably on the edge of three of the busiest shopping areas – Holborn to the west, Cheapside to the east and the Strand to the south. During the day it thronged with people and at night the large glass shop windows were lit up with gaslight, twinkling through the London fog.

How Priscilla did this, and where she got the money from in an age where there were significant legal impediments to women owning their own business, not least because they had no legal right to property or ability to borrow money, is a mystery. But, somehow, Priscilla did manage it and she was doing well, achieving that extraordinary feat of being a single, financially independent young woman and business owner in the 1830s.

Priscilla was part of a new breed of young women coming into the city from the countryside to work in the clothing, retail and hospitality sectors. They were known as working girls and considered not quite respectable, making a living without the help of a man, sometimes living alone and walking the streets unchaperoned. Newspaper columns were written about them. Nevertheless, these bold young women were usually defiant, flaunting the ultimate symbol of their independence – a key to their own front door. A music hall song of the time ran:‘She could look after herself, knew her own mind and had her latch key, and was too worldly wise to be taken advantage of or got around.’

But was she?

In 1838 Priscilla found out she was pregnant. Emily was born on 30th September 1838 at 101 Claremont Square in Clerkenwell. The identity of Emily’s father is a mystery; however, it seems likely that he was a man named Frederick Lambert. Certainly, in the 1841 census Priscilla calls herself Mrs Lambert (although there is no evidence that she had married). She is living with Mr Frederick Lambert (occupation, clerk) and two-year-old Emily Lambert. Also living with them was fourteen-year-old Caroline Swain, Priscilla’s youngest sister, who was presumably brought down from Preston to look after baby Emily, while Priscilla went off and did the necessary job of earning money making bonnets. What happens next is a mystery. There is no trace of Frederick Lambert after this; he vanishes completely.

In contrast with the candid way that Emily writes about her life in the theatre, she is discreet about her childhood. The public are only allowed the briefest glimpse into a sugar-coated world, where the city of her youth is lined with tall trees full of singing sparrows with glossy feathers and bright eyes. There is a delightful fruit seller with a big basket full of ‘ripe, rosy, juicy cherries’, and the New River ran ‘bright and sparkling’ through the Terrace – which must be an outright lie, because a river running through to central London would have been more like an open sewer, with all the detritus of human existence flung into it.

Clerkenwell was not the poorest area of London – Whitechapel just next door and Bermondsey across the river competed for that prize. However, alongside Southwark it was a close runner-up, with pockets of the destitute mingling with the poor working class and even a few lower-middle-class streets. When Charles Booth conducted interviews for his poverty maps of London, a policeman described Clerkenwell as ‘the melting pot’ of London ‘where all the stolen silver or jewels come to be melted or disassembled’. Some contemporaries might have put the unmarried mother, Priscilla, into that category.

In the fictional childhood of Emily’s memoir, however, there is a strict God-fearing mother (a career as a bonnet maker, or in fact any suggestion that her mother worked at all, is never mentioned), and there is also a father whom we are told is a barrister. Frederick Lambert was certainly never a barrister, nor was the man whom her mother did eventually marry and whose name Emily would take, Edward Soldene. He did work in the law, but only as a much lowlier legal clerk.

Moreover, Emily places herself squarely in the middle of the middle classes:

When I was a little girl, nurse told me if I was not an exceedingly good girl and did not do exactly as I was told a big dragon fly would sew up my eyes with an unbreakable multi-coloured web.

Emily would never have had a nurse – an auntie maybe, but not a nurse. There was also talk of governesses taking her to chapel, being sent off to an academy for young ladies in Islington, and housemaids taking orders from her mother. If Emily didn’t eat dinner her mother would allegedly say, ‘All right Mary, put it in the safe for Miss Emily’s tea.’

However, it does not seem likely that Emily grew up with her mother. Her descriptions of youth are mainly rural – a picture of a bucolic, timeless childhood running across fields, picking fruit in orchards, hiding in woods surrounded by cousins and being chased by aunts, a world away from the dangerous muddle of Clerkenwell.

Like so many children born out of wedlock, Emily seems to have been sent away to be brought up by her maternal grandmother, Katie Swain, and the large extended family that lived in the villages surrounding Hitchin in Hertfordshire. Katie was now a widow and the landlady of The Horse and Groom Inn in Preston. Emily’s aunts ran the rival pub in the village, The Red Lion, and her uncle, Charles (my great-great-grandfather) ran a pub in Langley Bottom down the road. Priscilla’s other brothers were blacksmiths and farmers, and her last sister had married a shop owner in Hitchin. There were plenty of family members to look after and absorb another small person without anyone noticing, and Emily had a tribe of young cousins as playmates. Sending Emily to the countryside left Priscilla free to run her business, keep her reputation and perhaps find a man who would marry her.

Amidst her childhood reminiscing, Emily also fails to mention that her grandmother Katie was a landlady. Female publicans were not uncommon in the early nineteenth century, but they inhabited a grey area of lower-middle-class respectability. Like working girls, inn-keeping was not quite decent. It was a habit of the Swain women to inhabit this grey area, which must have made it easier for Emily herself to get into a less than respectable profession later on.

Instead, Emily’s childhood stories are of the vicar falling asleep in her grandmother’s parlour after lunch, and picking flowers in her grandmother’s greenhouse, which she puts inside the Bible to take to church with her aunts. She tells of being caught by her grandmother reading a copy of Don Juan which she had found in an attic, inside a truck marked Mont Réal (the old name for Montreal, a souvenir from someone’s Canadian soldiering), and getting a good smacking in the orthodox manner with the slipper because ‘the authorities’ did not approve of ladies reading. It’s all very respectable. She paints a picture of a rural ideal: kisses behind haystacks, secret dells to lie down and daydream in on a hot summer’s afternoon, being sent out to gather snow to put in the big bowl of pancake batter for Shrove Tuesday, maypole-type rituals and ancient country festivals that at the beginning of the twentieth century Emily laments having disappeared. These are hardly the scribblings of a child brought up in inner-city London.

But all this was to change in 1849 when Priscilla gave birth to a little girl – Emily’s sister, and her closest friend and companion, Clara Ann Soldene, later to become famous as the actress Clara Vesey.

While Emily was picking cherries in orchards, back in London her mother had somehow uncoupled herself from the mysterious Frederick Lambert and struck up a special friendship with another clerk in a lawyer’s office, called Edward Soldene. How and why she married him is a mystery, but on 4th May 1848, at the age of thirty-seven, Priscilla finally walked down the aisle. Clara was born a year later, and eleven-year-old Emily was brought back to London and became part of a family unit with her mother and the man whose name she adopted, Edward Soldene. The new family moved into the top half of a small mews house in Islington just off the City Road.

However, things were still not quite what they seemed. Edward Soldene was a bigamist. He already had a wife. In fact, he’d had another wife for nearly twenty years, and five other children too. Priscilla must have known this because Sara Soldene and her children lived (conveniently or inconveniently, who knows?) just around the corner from them in Islington. And it wasn’t as if Edward had left his former wife and moved in with Priscilla and his new family. Seven weeks after Clara was born, Edward Soldene had another baby with Sara, a little girl called Sarah Ann – a half-sister for Clara. On the night of the 1851 census, when Clara was two years old, Edward chose to be at home with his first wife Sara and the six children they’d had together. Priscilla, Emily and Clara are recorded as living in the mews house on their own, and all three of them are given the surname of Lambert. Priscilla even calls herself Mrs Lambert, which would make her a bigamist as well as Edward Soldene. Given the prevailing moral climate, it’s not surprising that Emily doesn’t dwell on her parents in her writing.

To be fair to Priscilla, the Victorians may have portrayed themselves as morally conservative, but the reality was more complicated, especially in the capital. Amongst the working classes, the older custom of couples living together without being married, often breaking up and recoupling once or twice in a lifetime, was still operating. Serial monogamy was quite normal. Things only changed at the beginning of the twentieth century when the introduction of state pensions and benefits meant that arrangements had to become more official. In an age when divorce was not an option unless you were very rich and prepared to see your petition debated in the Houses of Parliament, it was simpler not to get married, just in case. Everyone accepted this – if you said you were married and behaved as if you were, you were treated as if you were. Even bigamy was not unusual. It was such a problem that in 1861 the government voted to make bigamy a Class One indictable felony, which in theory meant it could be punished by death. Men made up the majority of bigamists in court, and forty-two per cent of them were, like Edward Soldene, aged from thirty to forty. It seems it was a dangerous age for men inclined to roam. In the days before social media and the internet, it was quite easy to hide and people just disappeared to start again.

However, whilst living together may not have been unusual, it did leave Priscilla and her daughters vulnerable. A man could walk away from cohabiting and suffer no ill effects, but a woman, having less earning potential and possibly children to feed, might quickly end up in the workhouse. Even if Edward Soldene did stick around, after he had paid his first family’s housekeeping expenses from his clerk’s wages, there would be little money to spare for his second family. So Priscilla had to carry on making bonnets to feed them, and Emily was probably brought back from the countryside to help look after her baby sister, Clara.

Mothers can provide daughters with a great example of what to do, or, perhaps more importantly, what not to do, and the consequences of Priscilla’s complicated love life were almost certainly not lost on her eldest daughter. For the next nine years Emily lived with her mother and baby sister in their small flat in Islington. She would have observed the comings and goings of Edward Soldene between her family and his other family round the corner. She would have been a witness to Priscilla’s attempts to pay the bills and extract financial help from this less than honest man.

These observations may well have played a part in the next big event in Emily’s life. On St Patrick’s Day 1859 Emily slipped out of the family house in Islington and made for a house in Cleveland Street W1, an address that would later become famous as the lodgings shared by William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and the headquarters of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Emily had decided to elope.

Over the years Emily would say, ‘I ran away when I was very young, but old enough to know better.’ However, there were good reasons she might have been tempted to marry twenty-four-year-old lawyer’s clerk, Jack Powell. He was the right age and had a good enough job; in fact he was more senior in his law office than Edward Soldene. And he was willing to get married. The 1851 census had revealed that there were between 500,000 and a million more women than men in the country, and the ratio was particularly disadvantageous in London. A quarter of twenty- to forty-five-year-old women were unmarried. The newspapers were full of columns of hand-wringing anxiety about a phenomenon known as The Surplus. Who was to financially support all these wallflowers? Women did not earn enough to support themselves, largely because they weren’t paid enough. The Surplus were potentially a massive drain. No woman wanted to be seen as part of this demeaning Surplus. Basically, a single man, of the right age, with an income and his health, could not be allowed to get away. Especially when her mother’s willingness to compromise herself without a ring on her finger seemed to have left them so vulnerable.

But Jack Powell had an added attraction – he had connections. His father was the journalist John Powell, a close friend of Charles Dickens, an association that was to have consequences for Emily later. But in the late 1850s when Jack started courting her, a whole world opened up to Emily of which no innkeeper’s granddaughter, or bonnet maker’s daughter, could have dreamt. John Powell had worked alongside Charles Dickens as a political journalist in the lobby and was then appointed the deputy editor of the newspaper launched by Dickens, the Evening News. They were both friends of the journalist George Hogarth; in fact Emily claims that Charles Dickens met his future wife, Hogarth’s daughter Catherine, while having supper at her father-in-law’s house. Nineteenth-century journalism was a louche, bohemian profession that gave access to the highest echelons of politics, arts and the aristocracy and also permission to mingle with the worst criminals and prostitutes. Armed with intelligence, wit and confidence, you had a rare social mobility. The Powells had a beautiful house on the banks of the river Thames in west London. Years later Emily wrote:

I was always ‘Oxford’ in my young days, when I used to see the race from the ‘Lookout’ of an old house on the Mall, Hammersmith – an old house, with an old garden, and an old and champion mulberry tree; in the season the grass beneath black with fallen over-ripe mulberries.

Bumping into the new Master of the Mint, a certain Macdonald Cameron, at a party in Sydney in 1893, Emily recalled a conversation:

‘How do you do Mrs. Poo-ell? So many years since we met. Don’t you remember? I used to come up to the Poo-ell place at Hammersmith on Sundays and have a whiskey and soda, and a pull on the river with the boys, and sit under the big mulberry tree in the garden and talk nonsense with you’.

‘Why of course’, said I, ‘and we called you “the baby” because you had such big, white arms’.

‘Jolly times those’ sighed the M.C.

Jack’s two brothers also had interesting friends. Both artists, they specialised in stained-glass windows and were part of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. The Powell boys mixed with the most exciting artists, critics and poets of the day, on the fringe of the secret society set up by William Holman Hunt, the Rossetti brothers and John Everett Millais, called the Brotherhood.

The Powell brothers were always welcome at Cleveland House, and Holman Hunt and Rossetti seemingly didn’t mind Jack turning up too with his witty, pretty girlfriend. Years later Emily was to recall the Brotherhood with fondness:

The Cleveland House always seemed to me a shrine, full of saints with their haloes in various stages of development, full of virgins carrying sheafs of lilies, full of the Divine One carrying little lambs. To me, always full of devotion and art, these things were lovely, and the to-be-brothers-in-law, friends of the Brotherhood, would often take me across to the studio of the then obscure but eminent ones. Regular Trilby business.