7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

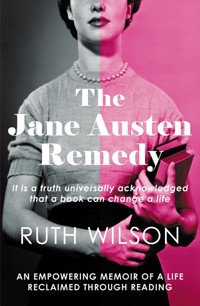

An empowering memoir of a life reclaimed through reading. 'Moving and inspiring, this is a book you want to start reading again, as soon as you have finished' SUSANNAH FULLERTON 'Wilson's memoir is essential reading for anyone who wants to experience and understand the unique comfort that Austen's works universally provide.' NATALIE JENNER Ruth Wilson first encountered Pride and Prejudice in the 1940s and has returned to Jane Austen countless times over the course of a long life. After her sixtieth birthday, she took the radical decision to retreat from her conventional married life and live alone while confronting feelings of loss and unhappiness. As Wilson read between the lines of Austen's six major novels, she felt herself reclaiming her voice and her sense of self. An uplifting memoir of love, self-acceptance and the curative power of reading, The Jane Austen Remedy is an inspirational account of nine vivid decades, unravelling memories and searching for small truths to help explain the arc of a life that has been both ordinary and extraordinary.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 393

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Praise forThe Jane Austen Remedy

‘While Ruth Wilson would never make such a claim for herself, she emerges from this discreet, wry memoir as quietly defiant as any heroine from the Jane Austen novels she so admires … All lovers of literature will relish Wilson’s skilful study of how the books we love become woven into the fabric of our lives, evolving with us as we age and helping us to grow up’

Sydney Morning Herald

‘The Jane Austen Remedy is a memoir, a guide to living a full and intelligent life, a work of thoughtful literary criticism, and also feels like an extended chat with a Jane Austen-reading friend … Elegantly and incisively written, full of insight and wisdom, moving and inspiring, this is a book you want to start reading again, as soon as you have finished’

Susannah Fullerton, OAM, FRSN, President of the Jane Austen Society of Australia

‘Ruth Wilson’s TheJane Austen Remedy isn’t just a beautiful and brilliant homage to the great novelist. It’s a tour de force memoir on the power of reading to light up a life at any age’

Devoney Looser, author of The Making of Jane Austen

‘This thoughtful, provocative book offers a window into a reading life and the ideas that have shaped a curious mind over more than eighty years. Books can make us better, Wilson urges, in this prescription for attentive, empathetic reading. The Jane Austen Remedy may just be the cure for what ails us’

Olivia Murphy, author of Jane Austen the Reader

5

The Jane Austen Remedy

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a book can change a life

Ruth Wilson

This memoir is dedicated to Jane Austen, her novels and her heroines.They have given me unexpected delights of heart and mindthroughout a long reading life.

Contents

Author’s Note

A memoir of any sort can be a revelation to the writer as well as to the reader. The experience of writing becomes part of the story, a creative act that might be considered either brave or foolish, perhaps both. It is possible that the relationships I examine in this reading memoir will be misunderstood. It may be that at times my memory falters. So it has been helpful to me – and might be useful to readers – to recall the warning issued by the narrator of Jane Austen’s novel Emma: ‘Seldom, very seldom, does complete truth belong to any human disclosure; seldom can it happen that something is not a little disguised, or a little mistaken.’

Introduction

Love and Happiness

Perfect happiness, even in memory, is not common …

JANE AUSTEN, EMMA

I was approaching sixty when questions about what it means to be happy assumed a special significance in my life, setting me on a new path that led to a careful re-reading of Jane Austen’s six novels. On a crisp winter day in 1992 I was sitting in my car, waiting impatiently at a traffic light; without warning the red circle started to spin crazily, and again without warning I was hurtled into a vortex of incomprehension. Momentarily I lost my bearings, but I managed somehow to make my way home and climb the stairs to my apartment, where I lay in a darkened room for twenty-four hours. The following day the condition was diagnosed as Meniere’s syndrome; the symptoms include hearing loss, nausea and vertigo.

The experience was disconcerting and left me shaken; but more disconcerting still was my experience a few weeks later, at a surprise party that had been arranged for my birthday. I entered a room to find sixty people, their faces covered with silver masks. I realised that behind the masks there were many good friends and loving members of my family, but as they clapped and cheered I was overcome by a strange antipathy. As the scene dissolved into a silvery nightmare, I felt like a character in Jean-Paul Sartre’s novel Nausea; overcome by a sensation that was palpably physical and eerily metaphysical, too. I was shifting in and out of my body as I went through Austenian motions of civility and courtesy. I greeted guests and made conversation, I responded to kind words, but I was in some place else. I was watching myself and wondering who I was. In a revelatory surge, I had stumbled into a moment of truth: I was out of love with the world and I was not happy.

I am often compelled to revisit that existential turning point. It was awful in the sense that I am filled with awe whenever I remember it: the awe of experiencing the astounding connection between body and soul. Because I think that my body was telling me that my soul, however such an entity is conceptualised, was ailing. My physical symptoms represented a state of mind; I felt insufficiently loved, less than happy, and touched by grief: for myself, for what I felt I had not achieved, for the years that lay ahead.

But how to explain it? I had lost no one. I had reached the age of sixty with my family intact and my days filled with projects that interested me. It might seem that my life, like that of Jane Austen’s heroine Emma, united some of the best blessings of existence. And yet, I was experiencing something more devastating than the distress and vexation that Emma encounters on her way to self-knowledge. I felt utterly lost. I sought professional help and was comforted by the assurance that Meniere’s syndrome sometimes mimics depression. Medication was prescribed, I gave up eating salt, and I resumed my busy routine.

On the surface, life continued to be ordinary. I managed to function well enough on a number of community committees and as a consultant for the implementation of classroom oral history programs, despite intermittent symptoms. When a family legacy came my way, I bought a small cottage in the Southern Highlands, a two-hour drive from Sydney. I reminded myself that, even as a child, I had always enjoyed my own company. Aware that I had spent my adult life deferring, like so many women of my generation, to the assumed male authority of the household, I decided to put the cottage in my name alone.

Everyone recognises Virginia Woolf’s phrase, ‘a room of one’s own’. I had surpassed Woolf’s aspirations. Suddenly I had not only a room, I was the fortunate owner of a whole house. And, as Germaine Greer averred in The Female Eunuch, a book that changed the way I thought about my place in the world, it was money that had made the difference between unhappiness and something else. Jane Austen knew this all too well, as the poet W.H. Auden intimates in a verse that conveys with mock horror his shock that an English spinster appears to advocate mercenary marriages.

The Bloomsbury legend, as Virginia Woolf became known, was herself damaged by a grim patriarchal background, but she famously showed the world of women that genius can accomplish writing miracles. Her fiction is full of women engaged in the struggle. From Clarissa in Mrs Dalloway to Mrs Ramsay in To the Lighthouse, women waver between acquiescence and independent action. In A Room of One's Own, Woolf took Jane Austen as her example in a lecture to female undergraduates. She lifted the author’s shimmering veil of associations and imaginings to reveal how astutely Jane Austen understood the role played by the patriarchy in normalising the subordination of women, and how effectively she camouflaged that knowledge.

It seems to me, however, that Woolf, for all her interest in women and fiction, closed the door on an equally deserving and much larger section of the female population: women like me who don’t necessarily write fiction. All women need their own space to inhabit, their own air to breathe.

I was less endowed with imagination than Jane Austen but more fortunate than she when it came to ‘pewter’, as she and her wealthy brother, Edward, referred to money. My family legacy was a miraculous gift, providing me with a refuge from the city at a time when I suspected that recurring physical symptoms might signal an unacknowledged form of emotional distress.

Thirty years later I read a novel called Secrets of Happiness. The American novelist Joan Silber creates six narrators who struggle to find moments of happiness among the pressures and tensions of everyday life in contemporary western society. Abby, my favourite character in the book, comforts her grieving son with a verse by Langston Hughes. The American poet exhorts us to hold fast to our dreams lest they should, like a broken-backed bird, die before they can take flight.

No words could better capture the mood of my life when I retreated from the city.

My cottage came to represent a piece of real estate in which my state of mind might be remedied. It stood at the top end of a steep and winding road, in a location comparable in size to Meryton where the Bennet family lived; also to Emma’s Highbury, ‘a large and populous village almost amounting to a town…' I started to spend my weekends there, getting to know a community like the one Austen described to her niece Fanny as ‘just the thing’ to be of interest to a fiction writer – or, in my case, a fiction reader. I was hoping for a remedy: a panacea for a malaise that I could no longer dismiss.

I had thought I was doing well enough, but as I was arranging the photographs that recorded a gathering on my seventieth birthday, I noticed that I was not smiling in any of them. I wondered why, for someone so privileged, I looked miserable. Was I becoming a misanthrope? I asked myself. The expression on my face seemed to embody Elizabeth Bennet’s observation to her sister Jane: ‘There are few people whom I really love, and still fewer of whom I think well … The more I see of the world, the more am I dissatisfied with it.’

I am reminded as I write now of Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day, a novel about a butler who looks back on a life lived in the shadows of other people’s expectations and his own sense of duty, eschewing risk and declining to embrace life on its own terms. I remember asking myself then how I wanted to spend the remains of my own days, perhaps not in those words. I knew one thing for certain: I wanted something to change. There and then I decided to stake a claim to my space, to make my cottage in the Southern Highlands into my permanent home, to spend my time trying to understand my malaise, to find a happier way of being.

After fifty years of marriage, it was a difficult, complicated and emotionally painful decision. My husband was, I think, bewildered. I had never discovered a way to convey to him the intensity of my own feelings, the waves of frustration and regret that swept over me periodically, strong feelings that men are prone to dismiss as female hysteria. I longed to make decisions without being challenged, to be the one who sometimes had the last word, especially in matters that were chiefly my personal concern. I was tired, I realised; I was especially tired of being surrounded by people whose values I could no longer pretend to share. I had no idea how it would turn out for any of us as a family, but it was, I thought, time to take my turn; a last chance to examine what had become of a girl’s once-upon-a-time great expectations of life.

I had been having recurring dreams in which sounds formed in my throat, but words failed to emerge. They were trapped in my larynx, struggling to be heard. My voice, which my elocution teacher had taught me to value as a musician would value a cherished instrument, had gone missing.

I wanted it back.

It occurred to me that my greatest love outside family and work had always been a love of reading fiction; of all the novels I had read, Jane Austen’s were my benchmark for pleasure as her heroines had been models for the sort of woman I wanted to become. A nostalgia for those books swept over me. So I decided to think of recovery as a rehabilitation of my reading life, and to start by revisiting the six novels. I wanted to re-read those passages that had made Austen’s fiction important to me: the bons mots, the well-worn quotations and the lively conversations. I didn’t know it then, but I was embarking on an untested approach to reading. I was making Austen’s novels a starting point for exploring the satisfactions and dissatisfactions of my own life, framed and illuminated by her fictional universe.

I had not been idle. I cast my mind back now to the years of my fourth and fifth decades, when I had plunged into a period of learning and doing: a postgraduate degree, participation in boards of management, coordination of intergenerational school programs, journal publications and a book about the art of interviewing. The curriculum vitae looked good, my endeavours had brought me rewards and even an award or two. But like the narrator in Nora Ephron’s book Heartburn I failed to grasp the irrelevance of what I was so busy doing at the time. When I contemplated the prospect of facing life on my own I connected with Isabel Archer in The Portrait of a Lady by Henry James. She undertook a solitary midnight meditation to calibrate her moral compass and consider where her destiny lay. I was inspired by her example, although I never reconciled myself to her decision to remain with a husband whose nature repelled her. But that was Isabel’s own fictional business.

I would do it differently; I would re-examine my lived life in the context of my reading life, hoping that I would better understand and hopefully transform my perplexed state of mind. So I decided to read all six of Jane Austen’s novels with greater intent; reliving the past pleasure but also opening my mind to other possibilities, bringing the full complement of my feelings, thoughts and lived experiences to the act and art of reading.

Austen’s fiction is sometimes concerned with improving the estate. So, I renovated my cottage at the top of the hill. It wasn’t as challenging as the task that Mr Rushworth faced at Sotherton, in the novel Mansfield Park, but I started with colour. I had the walls painted yellow, the colour of sunshine, inside and out. A craftsman in a nearby village copied a Frank Lloyd Wright design for glass panes and inserted them in a frame to make a welcoming front door. I chose a tall slender lamppost to light the entrance at night. A friendly gardener helped me plant beds of cream and green hellebores under the mature rhododendron trees and masses of graceful bluebells under the birches. From a newly built elevated reading room with vast windows I looked out on a maple grove and up a thickly wooded hill. Like Emma, I rejoiced in the ‘exquisite sight, smell, sensation of nature, tranquil, warm, and brilliant after a storm’; the difference was that Emma’s storm was past, and mine was still raging inside me.

My life seemed to have been following a decade-long pattern. It turned out that I would live in the cottage that I called Lantern Hill, after a favourite childhood book, for almost ten years, during which I discovered just such a small piece of canvas in regional Australia as the one that served Austen as she sketched her typically English comedies of manners. I lived alone but I was less lonely than I had been earlier in my life. People made judgements; I didn’t heed them. Some asked questions; I didn’t answer them. Others – mainly women – understood, because they, too, had experienced the unbearable loneliness of marriage. And the only friends I retained were people I cared for and about.

I filled my days with reading, sometimes alone, sometimes in the excellent company of other Austen readers. These were different ways of reading, and each had its rewards. My three daughters remained, as always, the closest and most beloved friends of all, my latter-day heroines. During this period, they taught me as much as they had, I hoped, learned from me.

For the first time in my mature adult life I took a risk. It was often daunting, but I soon felt that being mistress of all I surveyed had its compensations. I thought that ‘to sit in the shade on a fine day, and look upon verdure’ as I opened the first of the six novels I intended to re-read might be, as Fanny Price concludes in Mansfield Park, ‘the most perfect refreshment’. I didn’t guess that, by re-reading Austen’s fiction at the age of seventy, I would be consoled in ways that would lead me to the best years of my life.

Chapter One

All About Austen

How quick come the reasons for approving what we like!

JANE AUSTEN, PERSUASION

My arrival in the regional town of Griffith in 1932 was dramatic for my parents. Not, perhaps, as dramatic as the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge that same year; charging out of the crowd on horseback, an Irish military man of dubious reputation managed to slash the ribbon and declare the bridge open before Premier Lang could do the honours. That was a political act, whereas the drama associated with my birth was more to do with geography. The doctor who was to deliver me lived in the neighbouring town of Leeton, about thirty miles away. Because he was delayed, my father – a doctor – delivered me himself.

The birth was, apart from that, uncomplicated, and I have stayed on for longer than I ever expected. The worst things that life has inflicted on me so far have dissolved into bittersweet memories that I recollect with wonder as I glimpse unexpected connections between my everyday life and my reading life. That’s what happened when I first read Jane Austen’s novel Pride and Prejudice, and it is also how I came to be a lifelong reader throughout a life that has been ordinary – if never having had to worry about food, shelter and security can be regarded as ordinary in a world where there is widespread want, homelessness and oppression. So it has been extraordinary as well, for the unexpected ways in which good fortune has commingled with and helped me through darker moments. For some years I have recognised that the love of reading has been one of the unexpected blessings in my life. Reading has defined my life and become a habit that is woven seamlessly into the way I think, feel and imagine.

I suffered the usual setbacks when I started to read. I was four years old and bewildered when first asked to copy letters from a blackboard onto my slate. My mother had enrolled me in the local convent because I was lonely at home and too young to accompany my brother when he started public school. I joined a class of children who had already mastered the alphabet, so the nun in charge enlisted the help of a young girl who was training to be a lay teacher. She was kind, gentle, encouraging and endlessly patient. Together we looked at letters and she gave them names; she explained that the written letters talked themselves into words, and although it took time I eventually found myself able to decipher the letters and mouth the words without help. By the time I was old enough to join my brother at the public school I could write and read a simple sentence so I was put into the first class.

This seems to me now to have been a poor decision. It was made by the school principal and it had repercussions. It meant that I never learned to mingle with other children in the big open kindergarten space that I passed every day of the week. I sometimes looked inside that room and wondered what it would be like to play at the miniature tables and chairs or to wander at will into areas in which toys and books were scattered everywhere. The principal’s decision meant also that I had no friendship base in the formal classroom where I sat every day at a desk and tried to understand what was going on and what I was supposed to do. At lunchtime, I drifted alone around the dusty playground, watching the games of children whom I didn’t know.

One day, I ventured to the furthest edge of the playground and was stopped in my tracks by the sight of an avenue lined by cherry plum trees and a procession of laughing children. They were following a girl and a boy who were wearing card board crowns covered in gold paper. Down the avenue they proceeded, beneath a canopy of green leaves and swooping branches. Occasionally one of the children stooped to pick up a ripe cherry plum. According to some unwritten law, the fruit was always handed to the King or Queen, as I presumed the crowned leaders to be.

I was entranced by this enactment of a fairy tale, and noticed another solitary girl similarly engrossed in the scene. We edged closer to each other. I am not sure who spoke first, but it didn’t take long.

‘My name is Ruth,’ one of us said.

‘So is mine,’ replied the other.

We were in the same class but had not previously exchanged a word. We walked back to the classroom arm in arm and asked the teacher if we could sit together. She agreed, and for the remainder of the year we had plenty of opportunities to enjoy our friendship and share an abundant treasure trove of fairy tales.

My taste in reading always has and still does accommodate fairy tales. I made their acquaintance in the company of Hans Christian Andersen and the Brothers Grimm. I met a different version in stories that our father read to my brother and me at bedtime. They helped prolong Scheherazade’s life night after night. I find their traces in Jane Austen’s novels, and in the work of contemporary writers as well. Angela Carter retells the story of Little Red Riding Hood in her collection of fairy tales called The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories with a powerful feminist consciousness of sexual politics. But if I were asked exactly how, when and where I began to think of reading as something that transported me beyond fairy tales and wishful thinking, beyond diversion, escape, entertainment or distraction, beyond even the postmodern charge to tell truth to power and similar political imperatives; if I were asked when reading became a source of nourishment and imaginative expansion, I would answer without hesitation that my reading life truly began with Pride and Prejudice.

The spell was cast the day I opened Austen’s most radiant novel. Sixty years later I thought of it as book magic, as I experienced the warmth of a glowing fire in my Southern Highlands home and remembered my Austen initiation on a contrastingly hot school day in summer. Then I was reading the book because it had been recommended by an English teacher whom I admired and respected. That is often the way, as the writer Rebecca Mead tells readers in The Road to Middlemarch, a book that celebrates her life with George Eliot. A retired English teacher with whom Mead read as a student was a crucial influence on her life. Together they prepared for her entrance examination. They analysed the Metaphysical poets and dissected Shakespeare’s tragedies. Inspired by the novel Middlemarch, Mead determined to change her life.

Jane Austen’s novels performed that service for me. They changed my life because they changed what I wanted to read and the way I connected with characters and ideas in fiction. More significantly than any other of the many novels that I have read and loved, Austen’s novels set the gold standard for the books I would choose to read from then on. They were what the Latin poet Horace called ‘dolce et utile’, sweet and useful. They shaped the course of my future: because of them, I became a lover of language, a teacher of literature, a parent-reader and, in a broader sense, an educator. My inner life has been nourished, illuminated and comforted by the empathetic voices, the complex characters and the challenging ideas in Austen’s novels – and they have changed, as I have done, over a lifetime. It really did not matter so much, I discovered through reading her novels, whether my parents fulfilled every need that I craved. What they lacked was often found in the pages of a book.

A character in Michael Cunningham’s novel The Hours wonders what book to give a sick friend, and resolves to give him one that will help him understand his place in the world, prepare him for change, and, indeed, ‘parent him’. If being parented means being encouraged to explore and reflect on your own life and relationships, then Austen’s fiction has helped me to feel that I was parented well.

I found my first copy of Pride and Prejudice in the school library. In those less sophisticated times, the 1940s, the library was just an ordinary classroom that had been fitted with cupboards and shelves. I am not sure how the books were arranged, but I doubt that the Dewey system was used by any of the English teachers who were responsible for keeping the books in order and who undertook voluntary library duty during the lunch hour. I was directed to the single library copy of Pride and Prejudice by Mrs Eason; she was my class teacher and she was on library duty that day.

My imagination was roused and stretched and shaped by what went on in Mrs Eason’s classes. She inspired a fascination with grammar. She shared stories of her own experience of reading and literature. She initiated me into the ‘terra incognita’ of literature, where, as Yann Martel, a master of magic realism, puts it, we are given more lives. She told us about Shakespeare and read to us from her own copy of Tales from Shakespeare by Charles and Mary Lamb. She had played the role of the spirited Rosalind in a university production of As You Like It, and she recited some of her lines, but my fancy was also taken by Jaques, and I was thrilled by his idea that ‘all the world’s a stage’.

Our teacher recited the seven ages of man in full, and I was especially interested in the infant and the schoolboy:

At first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like a snail

Unwillingly to school.

These were ages within my own range of experience. The speech offered me new words to think about and listen to in my head. I did not understand why ‘mewling’ and ‘puking’ were words to associate with babies, but they did not sound pleasant to someone who, as the younger child in the family, had never held a baby in her arms. They did not even taste or feel pleasant, I thought, sensing a poet’s hypersensitivity to words as physical sensations: ‘as sounds to be plumbed, as weights on the tongue’, Seamus Heaney wrote of words that appeared in the poetry of Geoffrey Hill.

The whining schoolboy, unwilling to go to school, was also quite outside my experience. My brother, only twenty-two months my senior, was my model, ever a bright and willing student. For both of us, school was a positive experience. Our days from the ages of five to sixteen were spent at the local public school, in a series of buildings that sprawled across a large expanse of land. They accommodated each stage of our education, from kindergarten to high school. Infants, primary and secondary departments adjoined each other along a stretch of road opposite a dense swathe of bushland, junior levels at the lower end and, at the other, a pseudo-Georgian red-brick building that housed senior secondary-school classrooms, a science laboratory, the staffrooms and the principal’s office.

School was only a twenty-minute bike ride from our home. I grew less and less lonely as I grew older, and I loved that morning bike ride. At times the weather was chilblain-frosty. Once, I remember, during a plague, it was thick with clouds of locusts blowing about in the hot wind. At its best, our climate was dry and crisp. That’s how my father fondly described it.

I loved everything about my country town in New South Wales’s Riverina region, not least its topography: Griffith is set on a low flat plain with a craggy rise called Scenic Hill at its edge, under the canopy of an expanse of sky that seemed to have neither beginning nor end. I loved its history, too. The idea of living in a township that had started life as Bagtown only twenty years before I was born seemed somehow auspicious, just as the Harbour Bridge had been. ‘In the beginning,’ my father recited from the prayer book we read on Friday night; and later, lying in bed, I thought, ‘In the beginning, there was Griffith, and now I live here.’

The cluster of cement-bag humpies that housed workers on an irrigation construction site was eventually referred to as ‘old Griffith’ and abandoned, while Griffith proper, a few miles away, was declared a town in 1916. By the time I called it home, the town had undergone a series of improvements; thinking about that now, I am reminded that the idea of improvement as a condition of progress, whether of place or person, threads its way through Austen’s novel Mansfield Park. But I would not enjoy thoughts like that until Jane Austen and I met, as destined, in the pages of her fiction.

I enjoyed ambling along the main street of the town, a wide tree-lined avenue with parkland on one side and shops on the other. It was in the park that I joined a throng of children who had been invited one Saturday afternoon to line up at trestle tables to receive drinks and chocolates to celebrate the coronation of King George VI. Wide beds planted with large trees took up the centre of the avenue, with plenty of spaces left for vehicles, whether horses and sulkies or box-like motor cars.

The first writing prize I ever received was for a high-school essay called ‘Shop Windows’. I described a stroll down Banna Avenue, and the delights of gazing at cakes and pies in the pastry shop, bolts of brightly coloured fabric in the draper’s emporium, and piles of Enid Blyton and Girls’ Crystal magazines propped up at the front of the newsagent’s display. The essay was published in the school magazine, Oasis. I couldn’t wait to show it to my mother, whose sometimes-gloomy moods were invariably lightened by any success my brother and I had at school. Her reaction was not quite what I had anticipated. She was pleased, even proud, but a little disturbed, too. If people read that I drooled over custard tarts they might also think that I was hungry, which – and it was an accusation – would bring shame on the family.

I was too excited by winning the essay competition to pay attention at the time. But much later in life, as I began to understand the ways in which reading plays games in the brain, memories of my mother’s ambivalent reaction also helped me to understand something about her disposition, and something important about the complexity of the reading process. Turning to theories to explain everyday activities can be tedious, but in the case of how we learn to read, the ideas of Louise Rosenblatt in an essay, ‘The Transactional Theory of Reading and Writing’, smack of common sense as well as theory. She explained reading as a transaction between readers and the black marks on the page. My own reading eyes were opened by Rosenblatt’s simple statement that all readers draw on ‘a reservoir of past experience’ as part of the transaction.

Once I explored my mother’s reservoir of experience I understood. I had learned over the years, from stories about her life as the youngest of seven girls, that my mother grew up in a household that struggled to put food on the table. The only time they ate fruit was at the Friday Sabbath meal, and then the girls shared the few oranges their mother could afford. My grandfather, Isaac, was too religious to be a good provider. He spent much of his time in the synagogue, praying. My grandmother, Hannah, was proud; so much so that she instructed her daughters not to reveal their poverty to strangers. Clearly, my mother’s memories and associated emotions were triggered by my prize-winning essay.

My own upbringing provided me with a reservoir of quite different memories that I would, in time, bring to my own reading adventures. I was fortunate to live in a comfortable house and to sit down to plentiful meals. I was always made aware and grateful that my father’s family had risen from immigration and penury in one generation. In the early years of the twentieth century, they had migrated from Palestine – then part of the Ottoman Empire – to Western Australia: first my grandfather, who worked in a general store in Geraldton, and then, when he could afford their passage, his wife, two daughters and infant son. A fourth child was born in Perth. In the fullness of time, they managed to send the oldest girl, Cecilia, to the Conservatorium of Music, and Ada, who was born in Australia, to study pharmacy. The only son, my father, fulfilled every Jewish parent’s dream and studied medicine. In their family, as in Jane Austen’s, one child, Rosie, was born with an intellectual disability; she was eventually sent to live in a succession of institutions and group homes, but never rendered invisible in the family history, as Jane Austen's brother, George, was.

My father came to Griffith as a locum, to fill in for a doctor who was on holiday. He was welcomed as a young bachelor. He was good social value, a competent sportsman in possession of a good singing voice. He loved country life so much that he decided to stay. He returned to Palestine to find a wife, brought her back to Australia from her home in Jerusalem, and built a private hospital in Griffith.

We lived near the hospital, in a red-brick house with symmetrical wings on each side of a wide, sheltering portico. There was a formal garden at the front, with two large circular beds planted with rosebushes and bordered with pansies. A silky oak and several jacaranda trees screened us from the neighbouring house on one side. I dreamed of climbing those branches and concealing myself in their foliage to hide from the ogres whose names I heard with increasing frequency in my parents’ conversations as I grew older.

By the time I was seven, Hitler and Mussolini had become regular visitors to the nightmares that disturbed my sleep, but the days were sunny enough for any child. It was my job to pick fruit as it ripened in the small citrus grove behind the house, and to fill a large straw basket with oranges, lemons and grapefruit. Behind a high, latticed gate a hanging yard with clothes lines stretching from post to post gave me plenty of room in which to play with imaginary friends. A dirt tennis court and cement swimming pool catered to my father’s and my brother’s love of sport. The house was harmonious outside and spacious within. The fact that it had been designed by an architect, in a place and at a time when domestic architecture was rare, was a matter of pride to both my parents.

The town itself hints at the spirit of the American architect Walter Burley Griffin, who designed Canberra. Burley Griffin conceived a plan for Griffith that was only partially fulfilled. Traces remain even today of the original design, which featured a distinctive radial pattern with wide tree-lined streets, ring roads and parks. The main irrigation channel was conceptualised as the key landscape effect of the city, a ‘sweeping curve around the central portion’, but that wasn’t quite the way it turned out. The railway had been planned as the focal point, and on the way to school in the morning I often leaned on my bike, waiting for the gates to open, when the train was in shunting mode.

The role of the river system, especially the Murray and its tributary the Murrumbidgee, was central to Burley Griffin’s plan. It remains a timely reminder of the significance of the river system for the Wiradjuri people who inhabited the slopes and plains of the catchment area long before Captain Cook disembarked on the coast of Australia. In Tara June Winch’s prize-winning novel The Yield, an Indigenous character called Poppy compiles a Wiradjuri language dictionary. Among these is the word bila, for a river. Everything reaches back to the bila, Poppy explains – all life and, with it, all time. Was it more than chance, then, that Burley Griffin, a white man, dreamed the same dream for towns of the aptly named Riverina, a region dominated by water flowing through a network of rivers and tributaries?

In a strikingly different spirit, Griffith and its sister town Leeton articulated, if only in embryo, a vision of white European architecture as well. Leeton was more successful than Griffith in fulfilling these intentions, boasting, along its avenues, examples of Art Deco that have survived later urban refurbishment. A handful of buildings in my own town made gestures to the style. The Rio Theatre was the less prestigious of the two picture shows, as we called them then, that brought popular entertainment and screen stars into our lives; it was Art Deco only in the stepped geometrical outline that capped the building.

In this theatre, to the burning shame of all who lived there and then (including myself and my family, all of us painfully and personally aware of the racial prejudice perpetuated against European Jewry), it was accepted without question that the Indigenous population should be seated separately, at the front of the theatre, on canvas chairs rather than in the upholstered seats enjoyed by other patrons.

But the Rio Theatre was also the site of my earliest successes in life. I was shy with strangers; tongue-tied was the word people used in those days. Cast as a tree in a school play that we were preparing for the Christmas concert, I listened attentively to every word spoken during rehearsals until they lodged themselves in my memory. The familiar story of the understudy who strikes it lucky came true when the girl who had been given the main part fell ill. I felt no sympathy; I simply struck while the iron was hot. I, who rarely spoke up in class, assured the teacher that I knew the lines. I delivered them to her surprised satisfaction, and two nights later I had my first experience of being applauded on the stage of the Rio Theatre. It was exhilarating.

To my delight, it was just the beginning of something new and intoxicating in my life. The cavernous Rio stage and its wings and its smell of dust eventually felt like a second home, where I acted in school plays year after year. Much as I enjoyed the plays, my happiest memories were my solo performances, when I recited to music. I discovered the genre of the musical monologue in my father’s tales of his early life and in his memories of his favourite sister, the one who went to the Conservatorium of Music. As a schoolgirl, she had accompanied herself as she recited to her family. The most popular piece in her repertoire was a melodramatic story of passionate love, theft and murderous revenge set in exotic-sounding Kathmandu.

Somehow, I came by the sheet music of ‘The Green Eye of the Yellow God’ by J. Milton Hayes, learned the words and persuaded Judith, a senior student who played the piano for school assemblies, to accompany me in a performance at a school concert. I sensed that I was giving a gift to my father. He was still mourning the premature death of his musical sister who, with her infant daughter, had been incinerated when the bus in which they were travelling in Palestine collided with a train. The windows were barred to protect passengers from the stones that were thrown at vehicles that carried Jewish passengers through Arab villages, so Cecilia and her daughter, Dalia, were trapped inside the burning bus.

I knew that my father was thinking of his sister when he asked me to recite the verses at home. Even without the music, without the staccato notes and thumping chords, the words carried their own message of high drama. Standing on the stage of the Rio Theatre and accompanied by Judith, I was as thrilled by my own performance as the audience seemed to be entertained by the melodrama.

The Lyceum Theatre, unlike the Rio, was dedicated to the silver screen. It was the elite picture show; as far as I remember, it welcomed no Indigenous patrons at all. My film-addicted parents patronised it at least twice a week – as frequently, in fact, as the program changed. The Art Deco touches were more elaborate than in the Rio. Inside both the foyer and the theatre, where we sat on upholstered seats, dimly lit glass bowls were held aloft by slender female figures. It was here that my mother, my father and I sat through two viewings of the film Pride and Prejudice, starring Greer Garson and Laurence Olivier, in a single week. That was during the year I turned fifteen.

I don’t think my parents would have guessed my thoughts as we sat together in absorbed silence. Even as I followed the story, I was considering whether my mother, with her nervous headaches, wasn’t just a little like Mrs Bennet; and my father – well, one could only wonder at how a fictional character with a tendency to poke fun at those less quick-witted than himself could be so familiar. I doubt that, watching the film, I detected the larger ironies with which the heroine must wrestle. These would only become apparent later, when I read the novel. For the time being, Mr Bennet’s abundance of wit and the humorous spirit with which the family greeted Mrs Bennet’s fluttering nerves did little to disrupt what were, in my mind, the domestic delights of life at Longbourn.

When it came to the daughters, who were so much closer to my own age, I was especially curious. Now I wondered how my parents perceived me in relation to the Bennet girls. If they imagined me as any of the five daughters, I would have liked it to be lovely Lizzy or perhaps gentle Jane. Although there was little reason to associate me with either, I really hoped it was not Mary; she, like me, had a bookish bent. I could see that both Elizabeth and Jane shone in comparison with the shallow and silly younger sisters. I thought they were amusing, but I was unsure about Mary. Although her hair was pulled back into a tight bun and she wore glasses with round wire frames – to give her, I suppose, a studious and plain look – she did not evoke my scorn. Perhaps I identified with someone who was less popular and pretty than her peers. But still, I thought, anyone would prefer the company of Elizabeth and Jane.

The year of our family viewing was 1947, so the film, released in 1940, must have made a late, or perhaps even a second, appearance in our town. Already the dark cloud of the Second World War that had hung over my childhood was becoming a memory. It was all opportunity and optimism in the wider world that beckoned us from everywhere, including the English classroom, in which a wise teacher introduced us to Jane Austen. He did it by way of As You Like It, the Shakespeare play we were reading and discussing in class. I had already been introduced to Rosalind by Mrs Eason; when I commented to Mr Connor that Rosalind reminded me a little of the heroine I had seen the previous night in a film called Pride and Prejudice, he pointed out that Elizabeth Bennet actually originated in a book of the same name. He promptly added the novel to our reading list.

That is how I came to spend my lunch hour one day in 1947, sitting at a desk in a classroom-cum-library, and reading, for the first of many times, the book that gave its name to the film. Not even reciting speeches from Shakespeare in my elocution class and at home for my father’s pleasure had prepared me for the first sentence of this novel. Like multitudes of readers before and after me, I read it several times. I heard it in my head. This was language, prose language, used as I had never heard it:

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.

Later, at home, I read the sentence aloud, as I had been longing to do ever since I scanned it silently in print. I savoured the sound. Simple as the sentence seemed to be, it was grammatically quite complicated. I recognised it as a periodic sentence, because we had been reading Dr Johnson’s essays in class and had been trained to spot something called suspended syntax, a strategy that delays the complete sense of a sentence till its very end. So, after a couple of readings out loud, I heard the suspense and drama created by positioning the main, arguably absurd, proposition at the end of the famous sentence. Of course, I didn’t know the sentence was famous then, but I was already on the way to discovering the key to an enduring literary triumph. The success of one of the most frequently quoted first sentences in literature is partially dependent on the author’s mastery of the language of grammar and the language of meaning. She managed to take my breath away by boldly blending the climax of a periodic sentence with the anticlimax of the proposition that wealthy men are necessarily in want of wives. Even at the age of fifteen I knew that could not possibly be true, let alone universally acknowledged.

I was a teenage girl in the 1940s: thoughts and images of marriage abounded in magazines and conversations with girlfriends. Nowhere, it seemed to me, could it be said that men, blessed with a good fortune or not, were in want; that seemed to be women’s lot. I recalled the question debated by Alice and the March Hare in the first book I had read quite by myself. Is saying what you mean, I wondered, the same as meaning what you say? The more I listened to my own voice, the more dubious I became. Who was telling this story? Jane Austen, whose name was on the cover, or someone else whose life had its origins inside the covers of the book? Reminded again of Alice, I grew curiouser and curiouser.