3,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Editorial Autores de Argentina

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Inside this book, you will find the dearest and most cherished memories I keep close to my heart. Here, I share the chronicles of a journey, not merely across lands and seas, but into the hidden depths of the soul. How a seventeen-year-old boy from Calabria managed to cross the ocean and the mountains to find his place in the world, in the great city of Buenos Aires. Life challenged me in ways that often resembled astonishing and unimaginable tales. I hope these words become a beacon of inspiration to help you navigate your own stormy seas and discover the courage that lies deep within you. I wish that every young person, as they dive into these pages, may find a reflection of their own struggles and triumphs. As you will see in these memoirs, life can be a demanding and passionate challenge, but it also grants us the wonderful chance to transform ourselves and find meaning, even in the darkest of times. Eugenio

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 267

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

EUGENIO SANGREGORIO

The Motive

Sangregorio, Eugenio The motive / Eugenio Sangregorio. - 1a ed. - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : Autores de Argentina, 2025.

Libro digital, EPUB

Archivo Digital: descarga y online

ISBN 978-987-87-6594-5

1. Autobiografías. I. Título.CDD 808.8035

EDITORIAL AUTORES DE [email protected]

Summary

PROLOGUE

CHAPTER 1

CONTRADA PALAZZA, BELVEDERE MARITTIMO, COSENZA, CALABRIA, ITALY

SAN SOSTI 1947

PALAZZA, ONCE AGAIN

SCHOOL

MY FIRST PAIR OF SHOES – 1951

BICYCLE

CHAPTER 2

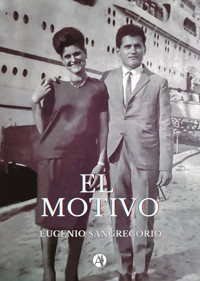

1955 FROM BELVEDERE MARITTIMO TO BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA 1957

THE JUDGE

THE TELEGRAM

THE DEPARTURE 1957

PORT OF NAPLES

THE “ENTRE RÍOS”

PORT OF BUENOS AIRES

CHAPTER 3

BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA 1957

MY FIRST JOB

THE LANGUAGE

PURCHASING MANAGER

CHAPTER 4

BUONGIORNO ITALIA MIA 1963

CHAPTER 5

I FIND MY TRUE CALLING, BUENOS AIRES 1964

IL BUCO, VILLA GESELL1969

CHAPTER 6

ELEONOR IS NO LONGER MY GIRLFRIEND

CHAPTER 7

I BECOME A FATHER, 1972

RENOVATION OF “IL BUCO”. SUMMER 1972 / 1973

ROSARIA’S JOURNEY 1974

CHAPTER 8

“NATURAL PARK” IN PROCESS

VALERIA, MY LITTLE GIRL. 1976

NEW VENTURES. A NURSING HOME

ARRIVEDERCI, BABBO 1977

“VOI TU” BY-THE-HOUR HOTEL, SAN FERNANDO 1978

CHAPTER 9

VALERIA’S FIRST COMMUNION 1981

“SEI TU”, BARADERO 1982

NATURAL PARK FOR THE REST OF SOULS, 1983

CARLOS PÁEZ VILARÓ, “LOS CIPRESES” CHAPEL, 1986

A TRIP TO ITALY WITH VALERIA, 1984

“LOS CIPRESES” NATURAL PARK, LICENSING

SEEKING A PRIEST FOR THE CHAPEL

CHAPTER 10

VALERIA TURNS 15, COCOYOC 1987

EPILOGUE

To my daughter Valeria, I dedicate this first chapter of my story. I once promised it to her as a gift for her 15th birthday—but it only found its way onto the page 37 years later.

PROLOGUE

Life itself carries no inherent meaning. We are compelled to invent reasons, again and again, to bear the weight of being. But beyond the motivations we discover along the way to keep moving forward, we sense there is one reason—the reason to live—that drives us, yet remains hidden until the day we depart this world.

I believe it is a kind of sentence to have come into this world called human. At birth, it is as if we are expelled from an immaterial universe free of suffering, one of indescribable peace. That is why I am tempted to say that with our arrival, we immediately lose something precious we once had: the fortune of never having been born. Some may say this is a pessimistic view, others may call it romantic—I believe it is biblical. After all, didn’t God cast man and woman out of paradise?

Since childhood, back in my native Belvedere in Calabria, I was obsessed with becoming someone in life. My desire to better myself financially took up the time I could have spent thinking about things that, while not material, were just as essential to truly living. Life’s struggles had hardened me. And so, I accumulated wealth—but lost moments I could never get back.

It was during one of my many trips, flying above the clouds to the land where I was born—away from work—that I had a moment of revelation. Only on these rare, quiet occasions, distanced from daily urgency, could I finally find space to pause and reflect on the rights and wrongs that had defined my past and present life. I realized that in my quest for fortune—to ensure prosperity and well-being for my daughter, my wife, and all of my family—I had set aside other values that are just as important, if not more so, than material wealth.

We live life looking forward, but we only understand it in retrospect, by looking in the rearview mirror. Now, as I reflect on my story, I feel the need to put it down on paper, so that not only my daughter, but also other young people, may understand that embarking on the journey of life can be as harsh as it is exhilarating. It is, in the end, the fight for life itself.

CHAPTER 1

CONTRADA PALAZZA, BELVEDERE MARITTIMO, COSENZA, CALABRIA, ITALY

I could begin this story by saying I was the second of three siblings, born into an illiterate farming family in Palazza—and that would be true, but it wouldn’t really be the story of my life in particular. Thousands of children were born under the same conditions, and yet what sets us apart is a mysterious something that still escapes our understanding. Be that as it may, the story I’m about to share is the journey that led me to forge my identity and become the person I am today.

The Sangregorios and the De Lucas, my parents’ families, were typical examples of the rural landowning middle class in Palazza, a picturesque little village with barely a hundred houses scattered across Belvedere Marittimo, in the region of Calabria, Italy. Despite having a certain amount of wealth, the Sangregorios lived austerely and impractically, due to their lack of common sense and considerable ignorance in financial matters. Though they had the means to grow their fortune, they chose a modest and frugal lifestyle, letting opportunities for prosperity slip by. I remember being barefoot as a child, since my grandparents considered buying shoes an unnecessary expense. That humble beginning may have planted in me, from an early age, a deep desire to get ahead and build wealth. But it wasn’t just about material success; raised in an environment where dependence was the norm, I also longed for the power to shape my own path without having to take orders. From a very young age, I aspired to freedom and full control over my life and future.

Everyone knows that achieving success, wealth, and happiness when coming from poverty is extremely difficult—many consider it impossible. That’s why, even though I had a clear idea of what I longed for, I constantly questioned my desires, unable to find a true reason to live. It was understandable, given a childhood like mine, where there was no visible horizon of hope, and the feeling of having no future filled me with anguish.

It’s painful for me to admit that my childhood unfolded in an environment lacking affection and encouragement. Still, I’m not going to blame my family for anything—thanks to them, I came to understand what I didn’t want in many aspects of my own life. I learned that while adverse circumstances can be a burden, if we approach them with intelligence, obstacles can eventually turn into opportunities. In this case, I firmly believe that knowing clearly what one doesn’t want for their future is one of the most crucial forms of wisdom in life.

The clearest example of what I didn’t wish to become came from my own parents. The misfortunes that continually and inexorably marked their lives pointed to a path I was unwilling to walk.

Rafael Sangregorio, my father, was a very handsome man, but he was illiterate. He was an only child, the product of a marriage between two people, one of whom had a strong authoritarian character: his mother, my grandmother Vincenza. She was known for her harshness, greed, and inflexibility, to the point of seeming, at times, devoid of emotion and reason. Even my grandfather Antonio, her husband, often appeared to live under her will. From an early age, my father was shaped to comply with the dictates of the family.

In contrast, Rosaria De Luca, my mother, was a young woman of striking beauty. Though she was also illiterate, she stood out for her sharpness and wit, as well as for her exceptional kindness. If anyone fell ill or needed help—whether a family member or a neighbor—Mom was always ready to offer assistance, care, and comfort. Many said she had inherited these qualities from her mother, my grandmother Nicoletta, a woman of great sweetness and compassion. By contrast, Antonio De Luca, my maternal grandfather, was a man marked by severity, with a harsh, dictatorial temperament.

When my parents first met, my mother was—according to what I’ve been told—in love with another man named Giuseppino. Sadly, this young man had neither wealth nor possessions; he was merely the foreman of a road crew that built and maintained the village roads, earning a humble municipal wage. My grandfather De Luca had little regard for his daughter’s feelings toward a man with no fortune. My grandmother, Nicoletta, though slightly more understanding when it came to matters of the heart, was submissive and tended to follow whatever my grandfather decided. In those days, love and marriage were often seen as separate matters.

That’s how, one afternoon at the Sangregorio household, both families came together. Over a few glasses of liquor, they began to talk business—or rather, to discuss my parents’ marriage. They agreed on the respective dowries, exchanging a few properties here and there, and the union was arranged. They were still very young when they married on January 27, 1934.

Beyond the financial arrangements, it’s important to note that Grandma Vincenza didn’t like Rosaria at all—as if she didn’t see her as a woman worthy of her son, or perhaps it was pure jealousy and rivalry. Whatever the reason, she saw her as an intruder and wasted no time or effort in making that clear.

After getting married, my parents settled on land owned by my paternal grandparents. The fields stretched across a hillside and were divided into several independent plots. On the three largest plots—each about five hectares—houses had been built. The first house sat on the lowest plot, along Contrada Palazza, the main road, and that’s where my parents established their marital home. It was a two-story house: they lived upstairs, while the ground floor was used exclusively as a workspace for managing agricultural duties. The second plot held a structure mainly used as a storage facility during harvest season. That area also had a chicken coop and stables where pigs and other animals were raised. Finally, farther back, on the highest part of the hill, stood what we called “the house up top,” where my paternal grandparents lived. In this setup, my parents had no privacy, as Antonio and Vincenza came down every day to work, walking nearly two kilometers from their house to the one where their son and daughter-in-law lived. They would settle on the ground floor each day to carry out their tasks, then return to their house at the top of the hill at night to sleep. This situation forced my mother into daily contact with her mother-in-law, who, of course, kept everything under control, driven by a persistent sense of hostility. That daily cohabitation only worsened their already strained relationship, leading to constant arguments and fights, often loud and heated. As one might imagine, none of it was heading for a happy ending.

Despite everything, I must say that there was love on my father’s side. Rafael loved Rosaria, but unfortunately, his feelings were not reciprocated with the same fervor. When she married, she had to let go of Giuseppino, the man she was truly in love with. Though my mother suffered in silence, my grandmother was well aware that her heart belonged elsewhere—and not to her son. Vincenza had a gaze that seemed to pierce both mind and soul, especially my mother’s, which only fueledher daily mistreatment. My father’s passivity in the face of it all was consistent with the obedience he had always shown as a son. My mother had no choice but to accept her fate, doing her best to live up to what was expected of her: obedience and sacrifice.

Just to illustrate the kind of dynamic we lived under: whenever there was a wedding to attend—be it a relative’s or a neighbor’s—Grandmother Vincenza would take my father as her escort, as if they were the married couple. Meanwhile, she ordered my mother and grandfather to stay home. Yes, even her own husband suffered the consequences of that dictatorial matriarchy.

Soon after their marriage, on October 25, 1934, Rosaria gave birth to her first daughter, my older sister, who, following family tradition, was named Vincenza. However, things didn’t improve much. Along with the challenges of being a first-time mother to a newborn, she had to bravely endure her fate of submission. The mistreatment didn’t cease, not even in her most vulnerable moments—such as when she became pregnant for the second time. One day, while my father was away, she was attacked in the field by an enraged ox that injured her in the belly, right where I was growing inside her. Rather than showing concern, the grandparents didn’t lift a finger. It was the neighbors who came to her aid, taking her to the hospital, where she was admitted for a few days. Fortunately, the pregnancy was not at risk. When my father returned and learned what had happened, he argued with the grandparents, who seemed indifferent to whether my mother and the child she was carrying lived or died. He did what he could, suffering in silence, but standing up to his own parents had always been a losing battle.

Just a few months later, on Thursday, March 2, 1939, I came into this world alongside my twin brother. It was a surprise to everyone—a true stroke of luck no one had anticipated, an unexpected two-for-one. Since I was the first to be born, I was named Eugenio, while my brother was named Filippo. Not long after, on Friday, September 1st, the Second World War broke out. I was only six months old, so I have no memory of the peaceful days that came before the conflict. For me, I was born into war and lived through it during the first six years of my life. Sadly, just two months after the war began, my twin brother Filippo passed away. Before I turned one, my father was drafted into the Navy, leaving my mother pregnant before heading off to the front. And so, on June 12, 1941, in my father’s absence, my mother gave birth to her second daughter, Anna—my younger sister.

We had to move into “the house up top” with Grandma Vincenza and Grandpa Antonio. Living under her in-laws’ roof, weighed down by three small children, surrounded by uncertainty, loneliness, and a lack of love from a family that subjected her to near slavery, the unfortunate Rosaria sank into utter desolation. It’s not hard to imagine that, by that point in her life, my mother’s dreams were already shattered, and she had painfully accepted her unhappy fate. The war offered no respite, but despite everything, her heart longed for some understanding—some pure, simple affection to momentarily soothe all the pain she carried inside. And so, she found that comfort in the arms of a stranger, a married man who lived in Marina di Belvedere. Of course, it was an improper relationship, but it gave her a feeling close to happiness and allowed her, even if just for a moment, to escape her sad reality.

That brief truce life had granted her didn’t last long. Soon after, she discovered she was pregnant again. Everything spiraled out of control, as expected, and it wasn’t long before the pregnancy—conceived in my father’s absence—could no longer be hidden. That small taste of love Rosaria had experienced was soon declared a crime. At the time, adultery wasn’t just condemned by society—it was also punishable by law, and her status as both a woman and an expectant mother only made things worse. It carried a harsh and merciless social stigma, along with severe legal consequences. Her lover, of course, remained protected by anonymity, while she—showing remarkable strength—never revealed his identity. Needless to say, the married man who had been her lover neither acknowledged paternity nor took any responsibility.

The outrage caused by the infidelity—not only within the family but throughout the entire town—was so intense that my paternal grandmother, without an ounce of compassion, expelled her not only from the house where we had taken refuge during the war, but from her entire property, completely disregarding the fact that her own small grandchildren would suffer the consequences. We were cast into a world of desolation, war, and hunger.

The condemnation was so severe that my mother couldn’t even seek refuge in her own parents’ home. The unyielding Antonio De Luca, feeling his family name dishonored by the adultery, refused to ever take her in again. Nonna Nicoletta wept, but my grandfather showed no mercy—he disowned my mother, disinherited her, and forbade her from ever setting foot in their house again. So absolute was his stance that he left this world without forgiving her, never allowing her a chance to say goodbye or seek reconciliation. He never wanted anything to do with her again.

Given the circumstances, I don’t know what would have become of us without the generosity of a family who knew my mother. They understood the situation and helped us navigate that difficult and shameful time. This is how we ended up moving to Contrada Olivella in Belvedere, a small locality about five kilometers from Palazza, where this family lived. When my father returned, he was confronted with this heartbreaking reality, and as expected, a matter of honor forced him to repudiate his wife. Nevertheless, through the neighbors, my father managed to find out where we were living, and he came to see us in secret to avoid my grandmother Vincenza’s wrath. Reuniting with his children and his wife, pregnant with another man’s child, must have been one of the most painful and humiliating moments of his life. There was no happiness in that reunion—only reproach and sorrow. What they said to each other will forever remain a mystery to me. We were nothing more than silent witnesses to that painful scene.

The secret encounters between my parents repeated themselves a few more times. However, the proximity of the towns and the indiscretion of a certain neighbor soon reached the ears of Grandma Vincenza, who reacted with fury. Faced with the implicit threat from his mother, my father ceased his visits, unable to defy her or take sides with his “adulterous” wife. This left us in a desperate situation—far from our family and with no shelter or means to survive. Finally, in the small corner of Olivella, on February 6, 1944, my half-brother was born, strangely baptized by my mother with the name Giuseppe. We naturally nicknamed him Pino. Much later, once we had settled in Argentina, we ended up calling him simply José.

In order to keep us fed, Mom worked temporary jobs while we were looked after by the family that took us in. But, not wanting to take advantage of their kindness, a year later, she decided to relocate us to Sant’Agata, a nearby rural village about thirty kilometers from Palazza, our hometown. With the war finally over, Mom found a more lucrative but riskier job. During these years, Rosaria had transformed into a woman of great strength, armed with resolve and courage. It was then that we moved once again, this time to San Sosti, a small town located forty-eight kilometers from Palazza. By then, I was eight years old.

SAN SOSTI 1947

After the war, the cities were left in ruins, and most people were living in poverty. Food was strictly rationed by law. In order to feed us, Mom was forced to turn to a dangerous but common activity in post-war Italy: smuggling. She had no other choice. Fully aware of the illegality and the risk, she knew it was the only way to put food on our table during a time of scarcity. The operation involved transporting liters of oil from San Sosti to Salerno and returning with kilos of salt—a 240-kilometer journey that took her to some of the most remote corners of the country. Sometimes, when I close my eyes, I can picture her on those mornings, a knife at her waist, the goods hidden beneath a disguise of luggage, constantly at risk of being discovered and imprisoned. I wonder what thoughts crossed her mind as she traveled through those desolate landscapes on long train rides, day after day, in an endless, exhausting cycle. How lonely she must have felt. It was then, very early in life, that I came to understand the quiet, admirable strength of my mother.

Inevitably, the day came when everything fell apart, and Mom couldn’t get the money she needed. That night, as she made her way home, worried that she wouldn’t have anything to feed us, she saw a loaf of bread in the window of a closed bakery. Without hesitation, she broke the glass with a kick, grabbed the bread, and brought it home so we could have dinner. Unfortunately, a neighbor witnessed the act and reported her to the authorities. As punishment, she was sentenced to six months in prison. No one showed her any mercy or compassion for her desperate circumstances—not even for the four young children she was forced to leave behind.

We survived on the charity of kind neighbors while Mom served her sentence. I honestly don’t have many memories of those months—and truthfully, I’m not sure I want to remember them clearly. Sometimes the mind takes our side, blocking out painful moments to shield us from the weight of certain memories. What I do recall, however, is making a firm resolution: I couldn’t just sit and do nothing. Even though I was only eight years old, as the oldest boy, I felt it was my duty to earn a living and help her. As soon as she was released from prison, I asked her to take me somewhere I could find work—ideally, a place where I could also learn a trade and build a future for myself.

My first attempt at work was at Domenico’s, a shoemaker who, having no children of his own, quickly grew fond of me. Every morning, he would greet me by pinching my cheeks so hard that my face turned bright red. Just remembering it now makes my cheeks ache like they did back then. As you can imagine, I wasn’t too fond of his enthusiasm. Though my employer cared for me deeply, the job itself turned out to be impossible. Because of post-war shortages, the small nails used for shoe repair were scarce and had to be reused. The trouble was, having been pulled out of old shoes, those nails were all bent and twisted. Since I had tiny fingers, my task was to straighten them with a hammer so they could be used again. As expected, I ended up smashing all my fingers. Needless to say, I didn’t last long in that painful line of work—though I did walk away with a valuable lesson in hammering nails into soles… and a few bruised fingers to prove it.

My next attempt at employment was in a bakery, where I believed I had found my calling, thinking it would be an easy craft. I couldn’t have been more mistaken. The task wasn’t difficult; I merely had to arrange the freshly baked loaves into baskets for transport. Once baked, they had to be removed swiftly to prevent burning. The problem was that the bread came out in large batches, and they all had to be removed at once. My small hands—once again the main characters—were constantly in contact with the hot loaves, leading to painful, irritating blisters. Fearing for my fingers, I asked if I could knead the dough instead, but perhaps due to my young age, they declined. A week was enough for me to decide, once again—for the sake of my poor hands—that I had to leave.

My third attempt at learning a trade was at a workshop that built coffins. Who knows how that brilliant idea even came about? I’ll never forget that first day. The master carpenter had assigned me the task of sitting at the end of a large board to act as a counterweight so he could cut a strip of wood. Sitting didn’t seem like a difficult job at first glance, but once I was in position, the minutes dragged on, and it became increasingly uncomfortable. Little by little, I grew tired of holding the same posture. At one point, I couldn’t take it anymore and made the mistake of trying to stand up. The result was catastrophic. I was practically catapulted into the air while the master fell to the ground like a sack of potatoes. I’ll admit that now it sounds funny, and I can laugh about it, but at the time, it was anything but. The look on the carpenter’s face was enough to make me think he was going to kill me. Terrified that he might hit me, I ran out of the workshop—and never even walked past its door again.

So, the weeks went by as I kept trying to earn my way in the world, until one early morning, just as the sun was rising, the carabinieri1 appeared at our door. I woke to the sound of a heated argument between them and my mother, unable to fully understand what was happening. What I do remember is the overwhelming sense of sorrow and bitterness in my heart. I thought it might be about the smuggling—but no, it was something far worse. It turned out that my father, urged by my grandparents, had officially filed charges of adultery. As a result, the court finally ruled that the three of us—Vincenza, Anna, and I—had to return to our father. “How can a judge be so heartless?” That was my childish thought. I couldn’t understand it. Even though my mother tried to stay strong for us so we wouldn’t be scared, I could feel the sorrow quietly eating away at her from the inside. It was the same sorrow that was eating away at me. It felt like the world had turned against us. I hated the judge, I hated the carabinieri, I hated my grandparents, I hated my father. Not always in that order.

There were, in fact, legal grounds for the court’s decision. To begin with, there was a law meant to protect children. According to that law, since my mother was poor, had committed adultery, and had an illegitimate child, the most appropriate course of action was for us to live with our father in our grandparents’ home, where we would be provided with “support and a proper environment.” Those irrefutable arguments were what separated us from her. There was nothing anyone could do. Pino, however, who was already four years old, had the good fortune of staying with our mother, since—being the child of another man—he had little to do with the Sangregorio family. I’d like to share a curious detail about him—a brief aside—something that often happens in Calabrian villages and says a lot about the society I grew up in: by pure coincidence, his biological father’s last name was also De Luca. However, since that man was married and never acknowledged him, the surname “De Luca” that Pino carried was actually our mother’s maiden name. That’s how it goes with many Italian surnames—people can share the same surname, the same hometown, without necessarily being related at all.

With no chance to appeal, we had no choice but to say a quick goodbye to our mother. The four of us melted into a single embrace, full of sadness and love. I wished time would stop so that moment could last forever—or rewind altogether. I said goodbye to Pino, who, despite being so young, understood everything that was happening and begged us through tears not to leave. My heart was in pieces. And so, “the children of Rafael,” as the judge’s order put it, were loaded into the carabinieri’s van that would take us back to Belvedere. As the door shut, we caught one last glimpse of our mother’s face, overflowing with tears. I watched her through the rear window, waving goodbye, until her figure faded from sight.

PALAZZA, ONCE AGAIN

Upon our arrival in Palazza, we were taken straight to my grandparents’ farm. It was grain harvest season, and everyone was busy with the work. The police van pulled up to the middle house—the one they used as a granary—and we were made to get out so they could hand us over to our family, in accordance with the judge’s ruling.

Both our grandparents and our father greeted us with a cold welcome, without a kiss, a hug, or even the slightest question about how we were. It was more like we were unwelcome. This was to be our new reality—none of them wanted us. They had brought us back only so the weight of the law could fall on “the adulteress.” All they cared about was punishing her, claiming their victory. I once overheard my grandmother say they wanted my mother to “pay for her sins”; our suffering meant nothing to them. The carabinieri had my father sign a receipt, as if they were delivering merchandise. After that, he ordered us to sit off to the side and not cause any trouble. I felt tired, depressed, hungry, and trapped in an indescribable uncertainty, just like my sisters.

My father and grandparents continued harvesting grain alongside the neighbors, who watched us from a distance and whispered mocking remarks about us because of our ragged appearance. I hugged Anna, who was sitting beside me and was on the verge of tears. After nearly two long, endless hours, they finally handed us a ham and cheese sandwich made with homemade bread—but without saying a single word to us.

I lost track of how many hours went by, but I started to think they had forgotten we were still sitting there. Around four in the afternoon, fed up and bored, I exchanged a look with my sisters and whispered that we should run away, taking advantage of our apparent “invisibility.” Sure enough, no one noticed when we stood up, holding hands, and made our way down a slope. And so, that afternoon, we wandered away from the farm without direction or purpose.

Suddenly, as if guided by some inner instinct, we were making our way toward the sea. We moved forward with confidence until we reached a stream that blocked our way. We stopped at the edge, unsure how to cross it because we were so small. We began discussing among ourselves, trying to figure out where to go. We would try one direction, then hesitate and turn back, only to set off again in another direction, constantly shifting our course as we searched for a way to cross the stream or find a road that might lead us somewhere.

The evening darkened the sky, and night gradually descended upon us. At one point, we stood frozen, disoriented, not knowing where to go. We remained motionless for what felt like an eternity. I started feeling scared—we were lost—but I tried to hide it so my sisters wouldn’t be more frightened than they already were, especially Anna, the youngest. The truth was, I had no idea how dangerous the situation we had gotten ourselves into had truly become. Suddenly, Dad showed up with some neighbors, and they took us back to the house. While I didn’t feel joy at seeing them, I was filled with an enormous sense of relief.

Our new life had become a torment, not only because of the mistreatment from our grandmother Vincenza but also due to the indifference and passivity of our father, who was a submissive man. Even though I wasn’t required to earn a living since I was just a child, and the judge had ruled that I should be raised by my wealthy grandparents, they still sent me to find a job, my fourth attempt at learning a trade. This time, Dad took me to a tailor in Acquara, about 500 meters from Belvedere. As with the previous attempts, I wasn’t just unskilled, but my fingers once again bore the brunt of it. First, since I didn’t understand how to take measurements, they had me sew on buttons, and sure enough, I spent the whole time stabbing my fingers with the needle. I don’t know what they expected—I was ten years old! In the end, I gave up. I didn’t want to hear about learning any other trade, and that’s when my grandmother decided I would help with the farm chores from then on.