11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

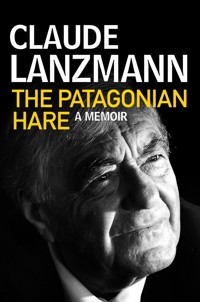

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The international bestseller: a cry of witness to the 20th century - the unforgettable memoir of 70 years of contemporary and personal history from the great French filmmaker, journalist and intellectual Claude Lanzmann. 'The guillotine - and capital punishment and other diverse methods of dispensing death more generally - have been the abiding obsessions of my life. It began very early. I must have been no more than ten years old...' Born to a Jewish family in Paris, 1925, Lanzmann's first encounter with radicalism was as part of the Resistance during the Nazi occupation. He and his father were soldiers of the underground until the end of the war, smuggling arms and making raids on the German army. After the liberation of France, he studied philosophy at the Sorbonne, making money as a student in surprising ways (by dressing as a priest and collecting donations, and stealing philosophy books from bookshops). It was in Paris however, that he met Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. It was a life-changing meeting. The young man began an affair with the older de Beauvoir that would last for seven years. He became the editor of Sartre's political-literary journal, Les Temps Modernes- a position which he holds to this day - and came to know the most important literary and philosophical figures of postwar France. And all this before he was thirty years old... Written in precise, rich prose of rare beauty, organized - like human recollection itself - in interconnected fragments that eschew conventional chronology, and describing in detail the making of his seminal film Shoah, The Patagonian Hare becomes a work of art, more significant, more ambitious than mere memoir. In it, Lanzmann has created a love song to life balanced by the eye of a true auteur.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

THE PATAGONIAN HARE

First published in France as Le Lièvre de Patagonie in 2009 by Éditions Gallimard, Paris.

First published in Great Britain in hardback and airport and export trade paperback in 2012 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Éditions Gallimard, 2009 Translation © Frank Wynne, 2012

Translated by Frank Wynne and revised by the author. The publisher wishes to thank Georgia de Chamberet for her help.

The moral right of Claude Lanzmann to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Frank Wynne to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Copyright © 1945, 1952, 1961, Arthur Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell & The Drunken Boat, translated by Louise Varese, reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corporation, all rights reserved.

This publication was granted a translation subsidy from the Centre National du Livre, French Ministry of Culture.

This book has been selected to receive financial assistance from English PEN’s Writers in Translation programme supported by Bloomberg. English PEN exists to promote literature and its understanding, uphold writers’ freedoms around the world, campaign against the persecution and imprisonment of writers for stating their views, and promote the friendly co-operation of writers and free exchange of ideas. www.englishpen.org

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 84887 360 5 Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 1 84887 576 0 eISBN: 978 0 85789 875 3

Atlantic Books An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZwww.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my son Felix

For Dominique

In the deep mid-afternoon, he stood illuminated by the sun like a holocaust on the graven plates of sacred history. Not all hares are alike, Jacinto, nor was it his fur that marked him out from other hares, believe me, nor his Tartar eyes, nor the peculiar shape of his ears. It was something that went far beyond what we humans call personality. The countless transmigrations his soul had endured had taught him, at the moments indicated to him by the complicity of God or some brazen angels, to render himself visible or invisible. For five whole minutes at noon he would stop at the same spot in the field, ears pricked, listening to something.

The deafening thunder of a waterfall that sets birds to flight, or the crackle of a forest blaze that terrified even the most foolhardy beast, would not have caused his eyes to dilate. The inconstant clamour of the world that he remembered, peopled with prehistoric animals, with temples that looked like withered trees, with futile, misbegotten wars, made him more temperamental and more cunning. One day he stopped as usual at the hour when the sun, at its zenith, poured down like lead on the trees, preventing them from casting shadows, and he heard barking, not of one dog, but of many, hurtling madly through the undergrowth. In a bound, the hare crossed the path and began to scurry away, the dogs giving chase, pell-mell, behind him. ‘Where are we headed?’ cried the hare in a voice that quavered like a lightning flash. ‘To the end of your life,’ howled the dogs in dogs’ voices.

The Golden Hare, Silvina Ocampo

Foreword

I have written a lot, pen in hand, throughout my life. And yet I dictated this book in its entirety, for the most part to the philosopher Juliette Simont, my assistant editor at Les Temps modernes and a very dear friend, and, when Juliette was occupied with her own work, to my secretary, Sarah Streliski, a talented writer. This is because I have experienced a strange and, I believe, somewhat rare adventure. Unlike most of the friends of my generation, who persist in clinging proudly to their pens and their spidery scrawl, I discovered, when I was given a computer shortly after my film Shoah was released in 1985, the extraordinary and entertaining possibilities of this machine, which I slowly learned to use and later mastered, if not all the possibilities it afforded, at least those features that were useful to me. When I was dictating, with Juliette next to me, both sitting before a large screen, I found it wonderful to see my thoughts immediately objectified, perfect in every word, with no deletions, no rough drafts. Gone were the problems I have always had with my own handwriting, which, in spite of the comments of those who thought it beautiful, to my eyes changed according to my mood, agitation or tiredness. I have often been sickened by my handwriting, which I found, to quote a remark by Sartre about his own, ‘sticky with all my juices’ – and he wrote so much that he must have known what he was talking about. And yet some insurmountable impediment had prevented me from fully embracing modernity. Moving directly from longhand to computer – having utterly avoided the typewriter – I found that I made very slow progress when working alone; I typed with one finger, I managed to objectify my thoughts, but what was sufficient for a police report was not practical for the work I envisaged, my hunt-and-peck typing disrupted the rhythm of my thoughts and killed the momentum. If I wanted successfully to conclude that terrifying task I had been grumbling about for so many years now, I needed an extension of myself, I needed other fingers. These belonged to Juliette Simont. But Juliette’s role was not limited to typing. I have been told a thousand times by a thousand different people that I ought to write the story of my life, that it was rich, multi-faceted and unique, and it deserved to be told. I agreed, I wanted to do it, but after the colossal effort that had gone into making Shoah, I was not sure I had the strength for such a massive undertaking. It was at this point that Juliette began typing or, what amounts to the same thing, insisting that I do something and stop prevaricating. And so one day I effortlessly dictated the first page to her, but waited months before moving on to page two, other urgent tasks taking precedence. I returned to it, but have been working on it seriously only for the past two years. While I dictated, Juliette was infinitely patient, respectful of my pensive, often lengthy silences, and her own silent, companionable presence itself inspired me. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that I express my gratitude.

I am also grateful to Sarah, who proved to be as patient as Juliette, and to my first readers, Dominique, Antoine Gallimard, Éric Marty and Ran Halévi, whose favourable reception encouraged me.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

A Note on the Author

Chapter 1

The guillotine – more generally, capital punishment and the various methods of meting out death – has been the abiding obsession of my life. It began very early. I must have been about ten years old, and the memory of that cinema on the rue Legendre in the 17th arrondissement in Paris, with its red velvet seats and its faded gilt, remains astonishingly vivid. A nanny, making the most of my parents’ absence, had taken me, and the film that day was L’Affaire du courrier de Lyon [The Courier of Lyons], with Pierre Blanchar and Dita Parlo. I have never known or tried to discover the name of the director, but he must have been very proficient, for there are certain scenes that I have never forgotten: the attack on the Lyon courier’s stagecoach in a dark forest, the trial of Lesurques, innocent but condemned to death, the scaffold erected in the middle of a public square, white, as I remember it, the blade swooping down. Back then, as during the Revolution, people were still guillotined in public. For months afterwards, around midnight, I would wake up, terror-stricken, and my father would get up, come into my room, stroke my damp forehead, my hair wet with anxiety, talk to me and calm me. It was not just my head being cut off: sometimes I was guillotined lengthwise, in the way a pit-sawyer cuts wood, or like those astonishing instructions posted on the doors of goods wagons that, in 1914, were used to send men and animals to the front: ‘men 40 – horses (lengthwise) 8’, and which, after 1941, were used to send Jews to the distant chambers of their final agony. I was being sliced into thin, flat slivers, from shoulder to shoulder, passing through the crown of my head. The violence of these nightmares was such that as a teenager and even as an adult, fearful of reviving them, I superstitiously looked away or closed my eyes whenever a guillotine was depicted in schoolbooks, historical writing or newspapers. I’m not sure that I don’t still do so today. In 1938 – I was thirteen – the arrest and confession of the German murderer Eugen Weidmann had all of France on tenterhooks. Weidmann had murdered in cold blood, to steal and leave no witnesses, and, without needing to check, I can still remember the names of some of his victims: a dancer, Jean de Koven, a man named Roger Leblond, and others whom he buried in the forest of Fontainebleau, in the aptly named Bois de Fausses-Reposes – the Woods of False Repose. The newsreels, in great detail, showed the investigators searching the coppices, digging up the bodies. Weidmann was condemned to death and guillotined before the prison gate at Versailles in the summer before the war. There are famous photographs of the beheading. Much later I decided to look at them, and did so at length. His was the last public execution in France. Thereafter, the scaffold was erected inside the prison courtyard, until 1981 when, at the instigation of François Mitterrand and the then Minister of Justice, Robert Badinter, the death penalty was abolished. But, at thirteen, however, Weidmann, Lanzmann – the identical endings of his name and mine seemed to portend for me some terrible fate. Indeed, as I write these words, even at my supposedly advanced age, there is no guarantee that it will not still be so. The death penalty might be reinstated, all it would take is a change of regime, a vote in parliament, a grande peur. And of course the death penalty survives in many places: to travel is dangerous. I remember discussing it with Jean Genet, because of the dedication of Notre-Dame-des-Fleurs [Our Lady of the Flowers] to a young man, guillotined at the age of twenty – ‘Were it not for Maurice Pilorge, whose death continues to poison my life…’ – and also because Weidmann’s name opens the book: ‘Weidmann appeared to you in a five o’clock edition, head swathed in white strips of cloth, a nun and yet a wounded airman…’, and mentioning my abiding fear that I would die by the so-called bois de justice [the guillotine]. He replied brusquely, ‘There’s still time.’ He was right. He didn’t much like me; I felt exactly the same about him.

I have no neck. I have often wondered, during nocturnal moments of acute bodily awareness spent anticipating the worst, where the blade would have to fall to behead me cleanly. I could think only of my shoulders and my aggressively defensive posture, forged gradually night after night by the nightmares that followed the primal scene of Lesurques’ death, which transformed them into a fighting bull’s morillo, neck muscles so impenetrable the blade glances off, sending it back to its point of origin, each rebound weakening its original power. It is as though, over time, I had drawn in on myself so as to leave for the blade of la veuve – the widow, as Madame Guillotine is colloquially known – no convenient place and no opportunity for it to make one. In the boxing world, they would say I grew up in a ‘crouch’, with a curvature of the torso so marked that an opponent’s fists slide off without the punches truly hitting home.

The truth is that throughout my whole life, and without a moment’s respite, the evening before an execution (if I was aware of it, as I frequently was during the Algerian War), and the day after in the case of a non-political capital punishment, were nights and days of distress during which I compelled myself to anticipate or relive the last moments – the hours, the minutes, the seconds – of the condemned men, regardless of the reasons for the fatal verdict. The warders’ felt slippers whispering along death row; the sudden clang of cell-door bolts slammed back, the prisoner, haggard, waking with a start, the prosecutor, the lawyer, the chaplain, the ‘be brave’, the glass of rum, the handover to the executioner and his aides and the sudden lurch to naked violence, the brutal acceleration of the final sequence: arms lashed behind the back, ankles crudely hobbled with a length of rope, shirt quickly slit with scissors to expose the neck, the prisoner manhandled, shouted at, then hauled, feet dragging along the ground, to the door, now suddenly thrown open, overlooking the machine, standing tall, waiting, in the ashen dawn of the prison courtyard. Yes, I know all these things. With Simone de Beauvoir I would be summoned to the offices of Jacques Vergès around nine o’clock at night where he would inform us that an Algerian was to be executed at dawn in some prison – Fresnes or La Santé in Paris, Oran or Constantine in Algeria – and we would spend the night trying to find someone who might contact someone else, who in turn might dare to disturb the sleep of Général de Gaulle, plead with him to spare this poor wretch to whom he had already refused clemency, consciously sending him to the scaffold. At the time, Vergès was head of a collective of lawyers from the Front de libération national (FLN) who practised what they called ‘la defense de rupture’, refusing to recognize the legitimacy of the French courts’ jurisdiction over the Algerian combatants, which resulted in some of their clients being more speedily dispatched to the guillotine. Very late one night, under the cold eye of Vergès, Le Castor (as Simone de Beauvoir was nicknamed) and I, gripped by the same sense of extreme urgency, managed to reach François Mauriac. A man was about to die, he had to be saved, what had been done might yet be undone. Mauriac understood everything, but he also knew that one did not wake de Gaulle and that, in any case, it would make no difference: it was too late, unquestionably. To Vergès, who was well aware of the futility of our attempts, our presence in his offices on the eve of these executions was a political strategy. One to which we consented, given that, from the first, we had militated in favour of Algerian independence, but to me the sense of the irreversible won out over everything else, becoming unbearable as the fatal hour approached. Time divided and negated itself like a gallop seen in slow motion: this scheduled death was endlessly about to take place. As in that space where Achilles can never catch up with the tortoise, so the minutes and seconds were infinitely subdivided, bringing the torment of imminence to its apogee. Vergès, notified of the execution by telephone, put an end to our waiting and in the early hours of morning, in the rain, de Beauvoir and I regularly found ourselves defeated, empty, without any plan, as though the guillotine had also decapitated our future.

When, in order to demoralize his own people and discourage further plots against him, Hitler ordered that the conspirators of 20 July 1944 be executed one after another, it became clear that the speed at which the executioners would have to work would compromise the precision and the concentration required for the ancient method of beheading by axe, the standard means of capital punishment in Germany. On 22 February 1943, the heroes of die Weisse Rose (the White Rose) – Hans Scholl, his sister Sophie and their friend Christoph Probst – died in their twenties beneath the executioner’s axe in Stadelheim Prison, Munich, after a summary trial lasting barely three hours, conducted by the sinister Roland Freisler, the Reich’s public prosecutor who had come specially from Berlin. Immediately the verdict was announced, they were put to death in a dungeon in Stadelheim, and Hans, as he laid his head on the block still red with his sister’s blood, cried, ‘Long live freedom!’ Even today I cannot call to mind those three handsome, pensive young faces without tears welling in my eyes: the seriousness, the dignity, the determination, the spiritual force, the extraordinary courage of the solitude that emanates from each of them, all speak to their being the best, the honour of Germany, the best of humanity. The 20 July conspirators were the first to die by the German guillotine: unlike its French counterpart – slender, tall and spectacular, lending itself both to being elegantly draped and to literature – the German version is squat, ungainly, four-square, easy to set up in a low-ceilinged room; consequently the blade, which has no time to pick up speed, is enormously heavy, and I am not sure that, like ours, it has a bevelled edge: its efficacy is due entirely to its weight. It was Freisler once again who acted as prosecutor at the trial of the 20 July conspirators in Berlin. In fact, he held every role: public prosecutor and presiding judge, he made the opening statements, questioned the witnesses and summed up against the accused. Their trial was filmed for Nazi propaganda purposes, to edify the public and ridicule those about to be guillotined.

Fouquier-Tinville during the Reign of Terror, Vychinsky, the prosecutor of Stalin’s show-trials in Moscow, the Czech prosecutor Urválek, barking like a dog at the Slánský trial, Freisler – they all descend from the same stock of bureaucratic butchers, unfailing in their service to their masters of the moment, affording the accused no chance, refusing to listen to them, insulting them, directing the evidence to a sentence that was decided before the trial began. In the footage of the 20 July trial Freisler can be seen, his face convulsed in feigned fury, cutting short the élite aristocratic officers and generals of the Wehrmacht, who are busy hiking up their trousers, which, having neither belt nor buttons, keep slipping comically to their knees, as the prosecutor moves from outrage to threats of contempt of court. But no one is laughing: the tortures suffered by the poor wretches before the trial, and the knowledge, etched on their faces, that they will die in the coming hours, set their features into unutterably tragic masks in which incomprehension vies with despair. The account of their beheading, in a dungeon in Moabit Prison in Berlin (which still stands, in the Alte Moabit district), is appalling: Freisler’s victims had to queue up to die, hands bound, ankles fettered by their own trousers, they were suddenly seized by the stocky executioner’s aides, who directed them either to right or to left – using an SS technique perfected elsewhere – for two guillotines were operating side by side beneath the low ceiling, amid screams of terror, the last shouts of defiance, amid the stench of blood and shit. In Moabit, there is no place for the beautiful – too beautiful – travelling shot the director Andrzej Wajda offers in his film Danton, where, in the midst of the Reign of Terror, Danton returns from Arcis-sur-Aube where he has spent several nights of passion with his mistress, arriving at the place de Grève at dawn, his barouche describing a perfect arc around the quiescent guillotine, elegantly draped in a long ribbon of night that, since it does not hide it completely, allows the ‘Indulgent’ a glimpse of the bevelled edge of the naked blade, a grim forewarning. Alejo Carpentier’s description, in the magnificent opening pages of El Siglo de Las Luces [Explosion in a Cathedral] is – no pun intended – of a different calibre: there Victor Hugues, a Commissaire of the Republic, former public prosecutor at Rochefort and a fervent admirer of Robespierre, brings with him to the Antilles both the decree – enacted on 6 Pluviôse, Year II – that will abolish slavery, and the first guillotine: ‘But the empty doorway stood in the bows, reduced to a mere lintel and its supports, with the set-square, the inverted half-pediment upended, the black triangle with its bevel of cold steel suspended between the uprights… Here the Door stood alone, facing into the night… its diagonal blade gleaming, its wooden uprights framing a whole panorama of stars.’

So many last glances will haunt me forever. Those of the Moroccan generals, colonels, captains, accused of having fomented – or of not having foreseen – the 1972 attempted coup against Hassan II of Morocco and his guests at Skhirat palace, who were driven to their place of execution in covered lorries open at the back. Sitting on facing benches, they stare at one another, and the photographer captured the moment when, in the dazzling sunlight, they see the firing squad that is to execute them. It is an unforgettable photograph, published in Paris Match, which captured what Cartier-Bresson called the ‘decisive moment’: we do not see the firing squad; instead we see the eyes of those who see it, who are about to die in a hail of bullets and who know it. In spite of fables of peaceful passing from life to death, such as Greuze’s painting, The Death of a Patriarch, or La Fontaine’s tale of ‘Le Laboureur et ses enfants’ [‘The Labourer and His Children’], every ‘natural’ death is, first and foremost, a violent death. But I never felt the absolute violence of violent death more than I did as I looked at that photograph, that snapshot. In that searing intensity, whole lives were laid bare before our eyes: these men were privileged, well-to-do members of the regime, they did not choose to risk their lives, unlike the heroes of the Resistance who, refusing the blindfold, stood to attention before the rifles and remained valiant even as the guns rang out. Why do I remember one face, one name so particularly – one I would never think to verify – Medbouh? He was, I believe, a general and devoted to his king, but the savagery and the vast spectre of the crackdown would not spare him. It is sweltering hot, sweat beads on his forehead, the irreparable is about to occur, and Medbouh’s last glance, frantic with fear and disbelief, evokes the greatest pity.

Another last glance, also from Paris Match: that of a hard-faced young Chinese girl screaming her revolt before the judges at the moment that she learns she has been condemned to death. Face contorted, torn between pain and refusal as policemen’s hands grab her and drag her away. In China, she knows, executions take place very quickly after sentence is pronounced, and the series of photographs published by Paris Match bears witness to the inexorable sequence of moments leading to her death. In the next photograph we see a second hand that, with overpowering force, pushes her head down to expose her neck but also to compel her to die in the position of a penitent. And, since executions there take place in public, to serve as an example, the last photographs show the pistol firing into the back of her neck and her battered, martyred body slowly slipping to the ground. Barely thirty minutes have elapsed between verdict and death. Other photographs, other films regularly reach us from China, all equally terrifying: a line of young men in black prison uniforms shot one by one, through the back of the neck, by a police executioner in white gloves wearing a peaked cap and full dress uniform, who forces each man’s head into the same penitent posture, as though the death penalty were the supreme act of re-education.

Still in China, the same China, the China of today. In Nanjing there is a Chinese Yad Vashem, solemn, simple, poignant, which commemorates the great massacre of 1937, in which the Japanese Imperial army, the moment they had captured the city, murdered 300,000 civilians and soldiers, killing in a thousand different ways, each more inhumane than the last. The goal was to terrorize the entire country and, beyond that, the whole of South-east Asia, all the way to New Guinea. They achieved that goal. Wandering through Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall with the curator who, in his humility, his calm, his lack of bombast in the face of the crushing weight of evidence, his reverence, the present incarnation of ancient suffering, ineluctably reminded me of the Israeli survivors in Kibbutz Lohamei HeGeta’ot in Galilee or at Yad Vashem during my preliminary research for Shoah, once again I realized that there is a universality of victims, as of executioners. All victims are alike, all executioners are alike. In Nanjing, to train the Japanese army rabble, bayonets fixed, in hand-to-hand combat, realism was pushed so far as to lash live targets to stakes as instructors gave detailed demonstrations of how and where the bayonet should be thrust: the throat, the heart, the abdomen, the face, all in front of the petrified faces of the guinea-pigs. Accounts and photographs bear this out, they show the faces of soldiers moving from crude laughter to rage and back again as they plunged their bayonets into the victims’ bodies. Those lashed to the next stakes awaited their turn, which came as soon as the previous targets breathed their last. The soldiers did not train on corpses; the dead feel no pain.

Through a long tradition, a punctilious codification, the Japanese became masters in the technique – the art, they call it – of beheading by sabre (something that can also be seen at the Nanjing Memorial), and organized contests between their most skilled men. How to describe, beneath the yellow summer uniform of the Mikado’s troops, its curious peaked cap framing with neck-cloths of floating fabric, the astonishing musculature of the swordsmen, steel bands of muscle that seem to be part of the sabre itself in that very moment when, gripped firmly in both hands, brandished high and vertical, it is about to sweep down a mere fraction of a fraction of a second later? Everything happens so quickly that the sabre passes through the neck while the head remains in place: it has no time to fall. What pride, what pleasure in a perfect execution, what smile of satisfaction on the face of the contest winners when, in the minutes after the competition, full of themselves, they posed beside the headless bodies, the bodiless heads.

And yet it is not in Nanjing, but 8,000 kilometres to the south, in Canberra, Australia, that, for me, was the culmination of horror. In Canberra there is a remarkable war museum, the Australian War Memorial, that is like no other in the world. Perhaps it is because Australia is not populous that every life is precious to them, and also because they have never fought a war in their own country, but only in distant lands. During World War I the Australian Expeditionary Force lost – who still remembers? – tens of thousands of men at Gallipoli, in the Dardanelles and on the French front. Between 1939 and 1945, on every front and in every branch of the army, many more selflessly spilled their blood to liberate Europe and Asia from barbarism. In Canberra, in one of the halls of the museum devoted to World War II , I could not tear my eyes from an extraordinary photograph, the work of two artists in the Japanese army: the photographer himself and the executioner. In an incredibly daring, low-angle shot, the photographer has succeeded in framing both executioner and his victim, a tall Australian, on his knees, arms pinioned, wearing a white blindfold. He has a chinstrap beard, his upper body is erect, his neck as long as a swan’s, his head barely bowed, hieratic, his face a mask of ecstatic suffering, like those in El Greco’s Burial of the Count of Orgaz. Above him, in the upper part of the frame, in the yellow uniform I have already described, the killer, face tensed in a rictus of concentration, arms raised to heaven, hands, white-knuckled, gripping the hilt of his sabre, which forms the apex of this devastating trinity. But though it may begin its trajectory on the vertical, it is on the horizontal that the blade will come to rest, having traced a perfectly controlled arc through space. Such is the mastery. Next to the two photographs of the Australian prisoner, one taken before the beheading, one after, is a letter, preserved like a precious relic, the letter that the executioner wrote to his family in Japan from the theatre of war in New Guinea, in which he gives details of his feat, boasting about the singular skills he required and marshalled to accomplish it (an English translation hangs next to the ideograms of the Japanese original).

But having spoken of the muscular backs of the swordsmen, having mentioned El Greco, I immediately think of Goya, the Goya of Los fusilamientos del tres de mayo, which I have so often stood and gazed upon in the Prado, turning away each time only with great difficulty, as though to walk away were to relinquish some supreme, some ineffable knowledge, utterly offered, utterly hidden. And yet in this remarkable painting everything is said, everything can be read, everything can be seen: the impenetrable wall formed by the serried backs of the Saxon fusiliers of the Grande Armée, black shakos pulled down over their eyes, swords slapping against their thighs, calves sheathed in black gaiters, left legs thrust forward, bent slightly in the classic position of a rifleman at drill, bayonets fixed, the barrels of their rifles perfectly aligned. The executioners are anonymous, all we can see are their backs weighed down with the trappings of an expeditionary troop, while the angle of their shakos tilted down over the sights of their weapons makes it clear that they are oblivious to the dazzled, dazzling faces of those they are gunning down. Between killers and victims, the light source, a square lantern, is set directly on the ground, its blazing light illuminating the night-time assassination with a vivid, surreal glow. The genius of Goya is that in the foreground, facing the lantern, the shakos, the rifles, standing out against the shadows and the hills of Príncipe Pío, and the vague intimation of the city beyond, it is the truly preternatural whiteness of the central figure’s shirt itself that seems to illuminate the whole scene. Two rival light sources are at war, that of the victims and that of their killers, the former so bright, so intense that it transforms the lamp into a dark lantern. Around the man wearing this shirt of light, the morituri seem grey or black, stooped, shrunken, hunched as though to offer no purchase to the bullets. A huddled mass climbs the steep narrow path to the place of execution. Suddenly, as they reach the summit, they see it all: the bloody corpses of the companions who went before them, the others, fatally wounded, already falling, and facing them, the firing squad relentlessly taking aim at each new group as it arrives. So as not to see, not to hear, they cover their eyes, their ears in a final posture of denial and of supplication. But in the centre, in the midst of those who have been shot, who are falling, at the absolute heart of it all, is he towards whom everything converges; kneeling yet huge, all the more huge because he is kneeling, in the instant before being hit, his shirt of light still immaculate, the man in white gazes, wide-eyed, upon his imminent death. How to describe him? How to depict his chest magnified, offered up to the gun barrels, its incredible whiteness, like an armour for his final hour? How to describe his mad, bulging eyes beneath the coal black of his eyebrows, his arms up, flung wide, not vertically, not crosswise but out at an angle, in a last gesture of bravado and sacrifice, of rebellion and helplessness, of despair and pity? How to convey his mute proffering, the message to his executioners written on his face, in every line of his body? In 1942, 130 years later, at the fortress of Mont Valérien in Paris, joining the ranks of those heroes of the night, the Communist Valentin Feldman addressed his unforgettable last words to the German riflemen about to execute him: ‘Imbeciles, it is for you that I die!’

Why is there no end to this? Twenty years pass, and we find ourselves crossing the place de l’Alma towards the Spanish Embassy, fiercely guarded by a police cordon, to plead, although we have no illusions, for Julián Grimau, sentenced to death for trumped-up crimes supposedly dating back to the Civil War. In reality it was because he was a militant member of the clandestine Communist Party of Spain, a membership he proudly and publicly avowed when he was arrested, before he threw himself from a second-storey window during his interrogation. Cruelly tortured, in spite of his broken wrists, Grimau was hurriedly executed in the dead of night, by the light of car headlamps in the courtyard of the Campamento military barracks in Madrid a few hours after our demonstration in Paris. It was 20 April 1963. El Caudillo was fiercely stubborn and, until he was in his final death throes – as we know, he was kept alive with tubes and wires for months as all Spain held its breath – he continued to send men to their deaths. On 2 March 1974 the Catalan anarchist Salvador Puig Antich was executed by the garrotte in Modelo Prison in Barcelona. This method of meting out capital punishment was codified as the garrotte vil, which can be simply translated as the ‘infamous garrotte’, but ‘vil’ in French can also be translated as ‘base’ or ‘lowly’: the condemned man dies sitting in a high-backed chair, his feet and hands clamped in vices, making it impossible for him to move; his neck is circled with an iron collar tightened by a screw at the back of the chair – slowly or quickly according to the cruelty or the professionalism of the executioner – crushing the carotid artery and then the spine. There is a specifically Catalan variation of the garrotte vil, where the collar is fitted with a spike that pierces the back of the neck as it crushes. Puig Antich was the last man to be garrotted under Franco, and for him too we protested in vain. The death penalty was abolished in Spain in 1978, so there is an end to this sometimes, somewhere.

Even as I write, the death penalty still flourishes throughout the world. I have said nothing of the anti-abolitionist states in the United States of America, each clinging to its own singular inhumanity, whether it be the electric chair, lethal injection, the gas chamber, the gallows. Nor have I said anything about the Arab countries, about the Saudi executioners who arrive ceremoniously at the place of execution in their white Mercedes, while the prisoner, already kneeling, head slightly bowed, waits for the white flash of the curved blade to behead them in public. They at least are experts, capable of competing with the Japanese executioners I spoke of earlier. Today, the time of the butchers has come (and I ask actual butchers to forgive me, for they practise the most noble of professions and are the least barbarous of men): why have we not been allowed to see the appalling images of hostages put to death under Islamic law in Iraq or in Afghanistan? Pathetic amateur videos shot by the killers themselves, which aim to terrorize – and succeed. Was this any reason to censor such images in the name of some dubious code of ethics, whose sole effect was to hush up an unprecedented qualitative leap in the history of global barbarism, to cover up the arrival of a mutant species in the relationship between man and death? And so these videos circulate clandestinely, and very few of us have been able to witness the true extent of the horror, struggling not to look away.

This is what happens: the film opens with a litany of verses from the Qur’an, which appear on screen as they are recited. As in pornographic films, there is no editing, no connection between the shots, which shift abruptly: suddenly the Tribunal appears, framed against a black background that fills the whole screen. In the foreground, kneeling, ankles shackled, hands tied, is the accused. Behind him, the Grand Judge and his assistants, tall, black-hooded phantoms, Kalashnikovs slung across their chests, meeting at the sternum, barrels pointing upward. The Grand Judge alone speaks. He does so in a deep, droning voice, he reads or does not read, it depends. He goes on speaking for some time, his voice becoming more furious, more sententious, a performance that culminates (he literally ‘makes himself’ angry) as the moment approaches when sentence is pronounced and carried out. The accused, whether or not he understands Arabic, knows that his fate is sealed, that at the end of the grandiloquent sequence of justifications adduced for the verdict, his life will be taken. Does he know how it will happen? Does he sense it? In the twenty or so ‘films’ I have managed to watch – all of them repulsive – I will retain only one. During the black-robed prosecutor’s long, furious tirade, the hostage remained completely motionless: no movement, unblinking, his gaze vacant, staring into space, as though he had already left this life and must now suffer the worst so that he could rejoin himself. Utter resignation. He is still a young man, his hair is curly but his face is gaunt, and he has clearly already suffered the most terrible physical and psychological agony, the hellish torture of experiencing hope before losing it forever. He shows no sign of fear, he is the embodiment of fear, made rigid by fear. As soon as the last word of the sentence is uttered, the Grand Judge, who has been standing directly behind the prisoner, brings his right hand to his belt and draws a huge butcher’s knife, brandishing it in front of the camera, shouting ‘Allahu akbar’ as he simultaneously seizes the prisoner by the hair and throws him to the ground, while one of the hooded henchmen grabs his ankles so he cannot struggle. It is with this butcher’s knife that he will behead the prisoner, but not before forcing the poor man to look into the camera, to look at us. And so, several times during the procedure, we will see the eyes of the prisoner roll wildly in their orbits. But a human neck, even one emaciated by starvation, is not composed entirely of soft tissue: there is cartilage, cervical vertebrae. The killer is tall and heavily built, but even he has trouble finding a clear path for the blade. So he begins to use it like a saw, sawing for as long as necessary, through the spurts and spatters of blood, an unbearable to-and-fro motion that forces us to live through, right to the end, the slitting of a man’s throat, like an animal, a pig or a sheep. When the head is finally severed from the body, the hand of the masked sawyer signs his work by displaying the head, placing it facing us, on the headless trunk; the eyes roll back one last time, indicating, to our shameful relief, that it is over. But the camera keeps filming, the hooded men have left the scene, a clumsy zoom shot frames the head and the torso, which now fill the screen, alone, in close-up, for a long moment, for our edification and our instruction. The face of the dead man and of the living man he was are so alike that it seems unreal. It is the same face, and it is barely believable: the savagery of the killing was such that it seemed it could not but bring about a radical disfigurement.

Chapter 2

Just as I took my place in the endless cortge of those guillotined, hanged, shot, garrotted, among all the tortured in the world, so too I am that hostage with the vacant eyes, this man waiting for the blade to fall. You must understand that I love life madly, love it all the more now that I am close to leaving it so much so that I do not even believe what I have just said, which is a statistical proposition, a piece of pure rhetoric that finds no response in my flesh, in my bones. I cannot know what state I shall be in nor how I shall behave when the last bell sounds. What I do know is that this life I love so irrationally would have been tainted by a fear of equal magnitude, the fear that I might prove cowardly if I had to lose that life through one of the evil acts described above. How many times have I wondered how I would react under torture? And every time my answer has been that I would have been incapable of taking my own life as Pierre Brossolette did, as Andr Postel-Vinay attempted to do, when, with sudden determination, like Julin Grimau, he jumped from the second-storey of the Prison de la Sant as he was brought in for questioning, and as many less famous but no less heroic people such as Baccot have done. I need to talk about Baccot because he is always with me; I am, in a certain sense, responsible for his death. It was in late November 1943, after class, in the boarders quadrangle of the Lyce Blaise-Pascal in Clermont-Ferrand. Though Baccot was studying for his baccalaurat in philosophy while I was already in Lettres suprieures, he knew that since we had returned to school that autumn I had been leading the Resistance at the Lyce. In fact, I had set up the Resistance network from scratch. I had become a member of the Jeunesses communistes during the summer and since coming back to school had recruited about forty boarders khgneux (preparing for the cole normale suprieure), taupins (preparing for the cole polytechnique) and agros (studying agronomy) into the nucleus of the Jeunesses communistes, with whose help I had recruited 200 others into a mass organization the FUJP, Forces unies de la jeunesse patriotique controlled, unbeknownst to them, by the Parti communiste franais (PCF). Such was the policy of the clandestine Communist Party at the time. Baccot, to whom I had barely spoken before then, faced me squarely, dark eyes blazing beneath his bushy eyebrows, his hair pushed back to reveal the cliff-face of his forehead; he was thick-set, stocky and exuded a concentration, a dark force. I want to join the Resistance, he said simply, but the stuff youre doing doesnt interest me. I know there are action groups out there, thats what I want to join. I asked him how old he was. Eighteen. I was not even older than him! I said, You know what action groups mean, you know the risks? He knew, he understood. I told him, Take a week, think about it, think hard and talk to me again.

What were we doing that did not interest Baccot? Beneath the Lyce Blaise-Pascal was a network of long interconnected cellars like catacombs. My only contact with the outside world, with the Party, was a woman, whom I knew only as Agla. She had smuggled three revolvers and some ammunition into the school and entrusted them to my care. A few friends, those I was closest to, and I would sneak soundlessly out of the dormitory at night thanks to my father I was adept at such things go down to the cellars and practise shooting at improvised targets. No one ever heard the deafening explosions that echoed in the depths, nobody found out what we were doing very few people even knew that the cellars existed. But there were times, on days of red alert or when I had been warned by Agla, that I would come to class with the revolver in the pocket of the grey school smock that was the standard uniform for boarders. It is difficult to describe this period, and few have done so well. Among the day pupils, there were a number of , boys with connections to the , some who were even in the . They knew who we were; we knew who they were; you have to imagine the schoolyard of Blaise-Pascal at break time, the factions watching each other, weighing each other up, scrutinizing each other and turning away. The kids from families of collaborators or were the same age as we were. At the time, Clermont-Ferrand had been occupied for a year (November 1942, the date of the Anglo-American landings in North Africa) by German troops, the and the Gestapo, ruthlessly supported by Darnands , but the Communist Party action groups the ones Baccot wanted to join were making life difficult for them: intimidation, suspicion, fear stalked both camps. We had managed to get two or even three copies of every key in the school, most importantly the key to the double gate in the central quad, the gate that led directly into town, enabling us to evade the caretakers and supervisors. Agla supplied me with pamphlets, calls to resistance, denunciations of Nazi crimes, advice, information on how the war was progressing, poems by Aragon and luard, texts by Vercors published by Les ditions de Minuit. We had divided Clermont-Ferrand into sectors. On weekends and Thursdays too we sneaked out of the lyce in groups of five to head for whichever sector we had been assigned: we worked calmly and quickly, slipping the tracts through letterboxes or under doors. In every group, two members acted as lookouts and we repeated these operations, careful to vary both times and places since distributing pamphlets almost immediately alerted the attention of the police and of the . It was almost impossible to work by night we did so only in extreme cases since there was usually a curfew, and even when there was not, the town was swarming with German patrols.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!