13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

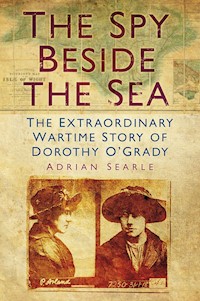

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Dorothy O'Grady is uniquely placed in the annals of espionage. She was the first Briton condemned to death under the Treachery Act of 1940 after she was frequently spotted on the outskirts of Sandown (a prohibited area on the Isle of Wight), insisting time and again that her dog had strayed. Had her appeal not saved her from the gallows, she would have been the only woman of any nationality to suffer death under the Act during the Second World War – indeed, the only woman to be executed in Britain for spying in the 20th century. Yet the full story of her extraordinary brush with notoriety and its enduring legacy has never been told, despite the fact that it has more than once dominated the front pages of the British press and inspired both a BBC radio drama and a novel. Now, with the benefit of access to previously classified documents, the truth underpinning the O'Grady legend can finally be revealed. Following her appeal she served nine years in prison for her wartime crimes – but was she really a spy in the employ of Germany? Or was O'Grady, as she insisted years later, a self-seeking tease who committed her apparent treachery 'for a giggle'? Or was there some other motivation which drove her to wartime infamy in a case which reverberated around the world? In The Spy Beside the Sea, author and journalist Adrian Searle examines all the evidence to reach a disturbing conclusion.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 The Spying Context

2 An Enemy Target: A Vulnerable Island

3 No More Milk till I Return

4 On Evidence that Admitted No Doubt

5 The Bulbs I Planted will Come Up Again

6 Better to be Thought a Fool than a Traitor

7 The Giggle that was Taken to the Grave

8 A Most Dangerous and Cunning Spy

9 Insight from Inside: A Very Peculiar Girl

10 Subplot: Vera the Beautiful Spy

11 Keeping Watch on a Spy Doing Time

12 Potent Mix: The Forces Driving Dorothy

Bibliography

Plate Section

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people have contributed their time, guidance and professional expertise to aid the process – challenging and rewarding in equal measure – of unravelling the complexities underpinning what I believe to be the definitive story of Dorothy O’Grady. Without their invaluable input and support this book would not have been possible. Indeed, at one point, when key documentation was reportedly ‘mislaid’ at The National Archives, and remains to this day unavailable for inspection, the encouragement of family and friends was the principal factor which dissuaded me from ‘throwing in the towel’ after a protracted period of research.

I acknowledge particularly the support of my son and daughter-in-law, Matt and Sarah, both of whom have contributed significantly to illustrating ‘the Dorothy book’, researching O’Grady’s familial background and checking the manuscript (along with other members of my family and my good friend, Jack Richards). I am also especially grateful to those with personal memories of Dorothy who have so willingly helped to illuminate the true character of this fascinating yet truly enigmatic woman. Their contributions are individually acknowledged in the text.

Many hours have been spent in an exhaustive examination, and re-examination, of archived material. The helpfulness and guidance of various professional custodians has substantially facilitated and enhanced the process. In this regard my thanks are extended in particular to staff at The National Archives in Kew, the British Library’s newspaper library at Colindale, the Imperial War Museum’s photographic collection, and the county records offices in the Isle of Wight and Essex. I am also grateful for the help of friends and former colleagues on the staffs of various newspapers who have searched their files for information and pictures.

The support and enthusiasm shown for this writing assignment from so many of my fellow Isle of Wight residents was important and is gratefully acknowledged. The O’Grady story has an obvious and particular resonance on the island, where it has long been enshrined in wartime folklore, awaiting final clarification of the truth behind it which this book project has sought to provide.

Finally, my thanks go to Mark Beynon (editor) and colleagues in the editorial and design teams at The History Press for entrusting me with this work and for the excellent job they collectively have made in guiding the production of the book.

INTRODUCTION

Dorothy O’Grady has rightly been called the oddest spy of the Second World War. The 42-year-old landlady of a guest house beside the sea on the Isle of Wight, short in stature, plump, bespectacled and married to a retired fireman, she was – to put it mildly – very far removed from the archetypal ‘cloak and dagger’ image of an embedded enemy agent. She did not seem a woman committed to the cause of bringing the country in which she had always lived to its knees in the traumatic English summer of 1940.

But spies, in truth, come in all shapes, sizes and disguises. Against the backdrop of a nervous nation, fearing invasion and obsessed with spy scares (ignited to a large extent by irrational suspicion), the outwardly unremarkable Mrs O’Grady was summoned to a local courtroom in August for breaching the wartime Defence Regulations. There was nothing especially sensational about it. She had simply been found with her dog on the foreshore, in an area to which public access had been denied in the interests of national security, and where, of course, her presence posed a potential risk to the operations of soldiers charged with keeping the enemy at the door from crossing the British threshold.

Yet, this was the start of a truly remarkable, barely believable, chronicle of events destined to grab worldwide attention as one of the most compelling ‘home front’ mysteries of the war. It is a story that, for the want of one crucial element, has provoked discussion, argument, bewilderment and controversy ever since.

Until now, Dorothy O’Grady’s story has been open to interpretation, and has indeed been interpreted several ways; it has never been rounded-off with an incontrovertible conclusion, though many people have wrongly assumed that it has. The key task for this book was to find an inarguable underlying truth and end for good the speculation. There have been many twists and turns along the way.

Decades after the war, one of the soldiers who apprehended her in August 1940 recalled how O’Grady’s behaviour had aroused his suspicions and how he had twice before warned her not to stray onto the forbidden beach near Sandown. The tearful woman’s unsuccessful bid to bribe him and his colleague with money – quite a lot of money – to let her go had done nothing to allay their suspicions. Yet, the attempted bribe apart, O’Grady made no serious attempt to resist arrest that day and, while the army may have harboured little doubt that she was up to no good, there were few local people who subscribed to the same view.

To most of her neighbours in Sandown, Dorothy O’Grady was a bit odd, very reserved with few, if any, friends – but probably harmless. Then again, the very fact that she did seem a bit different from the norm, and had moved to the Isle of Wight only a short time before the war, was probably enough to convince some sections of the civilian population that they had a spy in their midst; perhaps the shadowy, sinister fifth column was at last showing its face.

Certainly, the military had decided to take no chances with O’Grady. They had handed her over to the police and the summonses had quickly followed. On balance, however, it seems improbable that the landlady was regarded by the civilian authorities as anything more than a relatively minor irritant. No attempt was made at this stage to detain her in custody pending her court hearing in Ryde.

The Isle of Wight was on invasion alert, vulnerable to attack, and was being rapidly equipped to defend itself following the British retreat from Dunkirk, the traumatic fall of France, and German occupation of the Channel Islands – all far too close for comfort. Dorothy O’Grady’s arrest would serve as an example to others on the ‘front line island’ that the free and easy days of roaming the beautiful, but now militarily sensitive, coastline of Wight were, at least for the time being, a thing of the past. It was a case of ‘bring her in, rap her knuckles, teach her a lesson, let her go’ – not a desperately serious situation for Mrs O’Grady.

But her next move in 1940 dramatically changed the whole character of the story.

Bailed to appear before magistrates to answer the two charges against her, she failed to turn up. ‘I was too scared to attend,’ she would say, after she was tracked down nearly three weeks later. Dorothy O’Grady’s flight from justice had taken her to the other end of the island, to the far west seaside village of Totland. It had also transported her from the relatively unimportant status of wartime trespasser to that of a suspected covert enemy agent, actively engaged in various acts of treacherous espionage designed to help the Nazi cause.

Before the year was out, she would be convicted on capital offences at a secret trial in Winchester – and sentenced to death. There is a story that, having said nothing in her defence, she left the courtroom that day with a Nazi salute. That is almost certainly the stuff of legend, but it is not entirely unbelievable. If O’Grady was a frightened innocent, she undoubtedly hid it well. Away from the public gaze, known only to those who were tasked with her custody in the immediate pre-trial period, she had gone out of her way to act the part of a Nazi spy.

Bravado, delusion or plain stupidity?

The arguments that have periodically ever since raged over this extraordinary woman’s true wartime status have broadly divided along the same lines: she truly was an enemy agent, actively working for the downfall of Britain; she somehow deluded herself into thinking she was a spy; or she simply pretended to be one.

O’Grady escaped the gallows, instead serving nine years in prison for lesser offences following a successful appeal early in 1941 against her conviction on capital charges brought under the new Treachery Act. She was still an enigma when freed.

Then, over the course of several decades, right up to her death in 1985, she repeatedly fanned the flames of uncertainty with an explanation that was truly bizarre. Interviewed by a series of incredulous journalists, she insisted that she had never been a spy but had very much liked the idea of being thought of as one. It made her feel important – a somebody. So, having been caught in a situation that suggested she might be working for the enemy, she had gone along with it for a bit of fun. A joke. ‘The greatest adventure of my life,’ she said.

If it all sounded decidedly weird to the journalists who reported her comments, most were convinced it was nothing more sinister. Dorothy O’Grady – jovial, chatty and more than willing to discuss her wartime escapade – was a strange woman.

But a spy? Surely not.

If it had truly been a joke – and that was the version of events she took to the grave – it had come perilously close to costing O’Grady her life. Still, most were prepared to believe her story, content to dismiss her exploits in 1940 as those of a thoroughly bored and lonely woman, deprived by the war of her livelihood as a landlady and the company of her husband, craving excitement and adventure at almost any cost. At most, they surmised, she had been foolish. Very foolish indeed. But, of course, ‘dotty Dorothy’ could never have been a spy.

Yet, she had clearly convinced the police, the military and even MI5 that she was the real thing, and there were some (myself included) whose minds were not closed to the possibility that she just might have been. Could she have been a lot cleverer than most people thought? Could her ‘joke’ have been a cover-up? It was possible to argue that O’Grady was in the right place at the right time to have been, potentially at least, an effective agent for the rampaging Third Reich.

That the Isle of Wight was vulnerable to attack in the summer of 1940 had been clearly recognised on either side of the English Channel. Indeed, in July 1940, Hitler had specifically earmarked its possible capture as one way of establishing a foothold on British soil. The broad sweep of Sandown Bay was a tempting landing place for an invasion force and O’Grady was ideally placed in Sandown to provide the sort of information that could prove invaluable in planning such a strike – the location of defensive strongholds, the military strength.

Nobody, apart from O’Grady herself, knew at the time of her many interviews that the account she gave of her life was, in places, short on detail and, in other areas, outright denial of the facts. Whether this was an extension of colourful wartime fantasy or deliberate lies to protect her ‘dotty but harmless’ image, or whether, in mid and later life, she had simply forgotten some of the key points, divides opinion to this day. Whatever the truth, she died with that image largely intact.

The balance shifted markedly in 1995 when the pages of Britain’s national newspapers were splashed with dramatic accounts, compiled from previously undisclosed documents at the Public Record Office (now restyled The National Archives), relating to O’Grady’s wartime court hearings, which had been held in camera, with the press and public excluded, such was the sensitivity surrounding her at the time. Those records, locked away, unseen, for more than half a century, seemed to tell a story vastly different from O’Grady’s own account.

They told of a woman whose pre-war life had been anything but the humdrum existence she had described. A woman who had already acquired a noteworthy criminal record in the years before her wartime arrest, including convictions before the age of 30 for forgery and theft. The suggestion now was that she had waited years to gain revenge on the British authorities for what she regarded as a wrongful arrest in the 1920s for prostitution. Apparently, she was perceived to have posed such a threat to Britain in 1940 that the then Director of Public Prosecutions was adamant she should hang. Whichever side of the argument over her guilt you adhered to, the documents now in the public domain proved one thing beyond all reasonable doubt: Dorothy O’Grady was a very good storyteller.

Statements from soldiers she had apparently tried to bribe for sensitive information jostled for space in the archived files at the Public Record Office with maps of the Isle of Wight’s coastline, highly detailed in O’Grady’s own hand with information on gun sites, searchlights, troop positions and concealed transport.

With understandable reasoning, a large section of the British media now condemned O’Grady as ‘the supreme mistress of the double bluff, who almost succeeded in helping the Third Reich invade Britain’. The case at last appeared closed.

Doubts subsequently resurfaced. It was quickly, and correctly, pointed out that, despite the raft of ‘new’ evidence, it could still be argued that the statements, maps and much of the remaining material used to convict O’Grady in 1940 might well have been ‘planted’ by her, deliberately concocted following her initial arrest, once she had concluded that her coastal meanderings had aroused suspicion or, at the least, some official interest. They might have been part of the elaborate plan she claimed she had dreamt up in order to fool the authorities into thinking she was a genuine spy (and, if that was true, she was worthy of a degree of grudging respect for the extraordinary amount of work she had put into it).

Alternatively, the newly released documents might simply have been evidence of spying delusions. Perhaps she had drawn the maps and bribed the soldiers because she truly thought she was a spy. Possibly that was why, when arrested in Totland, she was found to be using an assumed name – something she tended to play down when giving the last of her colourful press interviews in the 1980s.

Or was her adoption of double-identity merely an extension of her big joke at the authorities’ expense? There again, maybe it was another clear sign that she was guilty as charged and desperately trying to evade capture when Totland’s village bobbies caught up with her. So run the arguments and counter-arguments.

The media may have decided en masse in 1995 that she had been a traitor, but there are writers of books on Second World War treachery and related topics whose adherence to the opposite view is at least implied. O’Grady was not referred to at all by Sean Murphy in his 2003 round-up of British traitors, Letting the Side Down. James Hayward did find space for her – briefly – in his Myths & Legends of the Second World War, published the same year. ‘In December 1940 a landlady named Dorothy O’Grady was sentenced to death for cutting telephone wires on the Isle of Wight, although later it emerged that her confession was false,’ he wrote, dismissing the whole thing as a fifth column scare.

Traitor or tease? Or tragically deluded? What was the truth about Dorothy O’Grady? Was it possible to reach a final conclusion or would she forever remain an enigma? The evidence used to convict her in 1940 was, given proper reflection, insufficient to answer any of these questions with a degree of certainty. Her own accounts, the words of a devious storyteller, had to be treated with caution. What was needed was expert opinion on her character and behaviour, and how both may have been influenced by the defining episodes in her pre-war story. Even this might still prove inadequate to reach a decision on whether or not she did betray her country, but it would surely enable a balanced, informed assessment to be made. Was that sort of information available?

It was. A second file of documents relating to Dorothy O’Grady had been compiled. It detailed her prison record before and during the war – and right up to her release from Aylesbury jail, five years early, in 1950. This crucial file promised a wealth of factual information and probable expert analysis on the enigmatic Dorothy, but it had been locked away since the day she walked from Aylesbury and remained hidden from public inspection until a successful application under the Freedom of Information Act secured its release from the Home Office in 2007. Then, just as this vital piece in the O’Grady jigsaw fell into place and I prepared to study the prison papers at The National Archives in Kew, came disturbing news about another major piece of the puzzle. It appeared the Home Office had, months earlier, asked for the temporary return of the initial O’Grady file, containing the documents relating to her trial and conviction, which had been released into the public domain in 1995. That file had never made it back to its allotted storage at Kew. It still hasn’t; officially it is ‘mislaid’.

Sinister? Mysterious? The questions inevitably have been asked. Was Dorothy O’Grady, posthumously, still managing to pull the strings of her own intrigue?

Fortunately, the newly released prison file did not disappoint. Indeed, it pushed the door wide open on the real Dorothy O’Grady. The details its long-hidden documents revealed carried her story from the extraordinary to a shocking new level. There had been another, crucial, factor which had driven her so perilously close to the gallows in wartime, a factor unknown to the researchers and theorists who had tried to interpret her life story. It put Dorothy O’Grady into a very distinctive category with few, if any, parallels. Finally, it was possible to reach a conclusion drawn from the full weight of evidential material as to her true status in wartime and throughout a life markedly less ordinary than most.

En route to its conclusion, this book sets out to present the first comprehensive dissection of all the known facts, all the theories and all the legends about Dorothy O’Grady. It examines her personal life and how her childhood and experiences as a young woman undoubtedly did influence her later character, behaviour and psychological make-up. It investigates possible links with proven Nazi spies and describes the far from straightforward nature of her imprisonment. The story is not told according to its strict chronology – from birth to the grave – but rather as the facts and changing perceptions of this enduringly fascinating woman emerged during her lifetime and following her death.

Mark Twain’s famously oft-quoted idiom that truth is stranger than fiction can seldom have been better applied than in relation to the remarkable story of Dorothy O’Grady.

1

THE SPYING CONTEXT

The process of placing the story of Dorothy O’Grady in its historical context can usefully begin with a summary of German espionage activity within the United Kingdom during the two world wars, together with the measures employed by Britain to deal with suspected covert enemy agents when caught. The eventual fate of those agents – not all of whom suffered the ultimate penalty – adds a further strand of background material to the scene-setting exercise.

Germany’s development of a spying ring in the UK prior to the First World War fell victim to an early and highly impressive counter-intelligence coup for Britain’s Secret Service Bureau, set up in 1909 principally as a reaction to the alarming growth of German military and naval strength. The fledgling bureau’s Home Section was tasked with countering foreign espionage in the UK – in essence, rooting out German agents – while its Foreign Section concentrated on gathering secret intelligence abroad. Under the leadership of its first director-general, Captain Vernon Kell, the Home Section (which in 1916 would evolve into Section Five of the newly formed Directorate of Military Intelligence – MI5) swooped on the German spying network as soon as war was declared in August 1914.

With Kell’s men acting on information gathered in the pre-war period, the enemy agents were rounded-up and immediately interned. Those caught in the net by the Bureau were the lucky ones. Eleven agents who later arrived in Britain as the war progressed were not so fortunate. All were condemned to death.1,2

They were convicted of spying under sections of the Defence of the Realm Act, which had entered the statute books a matter of days after the war’s declaration. Most were tried by military courts martial, though two faced criminal proceedings at the Central Criminal Court (Old Bailey) in London. All eleven were executed by firing squad at the Tower of London between November 1914 and April 1916 – either in the miniature rifle range, since demolished, or in the Tower ditch. No women suffered the same fate, though Swedish-born Eva de Bournonville came perilously close when she was sentenced to death at the Old Bailey in January 1916 for attempting to communicate sensitive information to the enemy. Reprieved on appeal, she then served six years in prison.

The legislation ushered in under the Defence of the Realm Act (popularly known as DORA) had provided the government with a raft of powers designed to meet the threat posed by the first official ‘state of national emergency’ in Britain since the Napoleonic Wars of 1799–1815. The Act allowed the introduction of wide-ranging regulations in pursuit of public safety and the nation’s defence in wartime. It paved the way for the drafting of new legislation in the immediate post-war period permitting the government to retain on a more permanent basis the right to impose the sort of sanctions hitherto reserved for wartime. Becoming law in 1920, this was known as the Emergency Powers Act.

Introduced by Lloyd George’s coalition government, the Act allowed a state of emergency to be declared whenever, in Parliament’s opinion, the nation’s essential services were threatened. The most noteworthy – and prolonged – use of the Act in the interwar years came at the time of the General Strike in 1926, when it was in force for a considerably longer period than the few days of the strike itself – after Stanley Baldwin’s Conservative administration forced the trades union movement’s general surrender, leaving the miners to soldier on alone.

Thus, the core legislation was already in place when war again threatened between Britain and Germany in the late 1930s. With the nation’s security once more at risk, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain successfully sought parliamentary approval in August 1939 for an Emergency Powers (Defence) Act. Becoming law on the 24th of that month, one day after the alarming news of Germany’s non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union, it armed the British Government with the powers to take whatever measures it saw fit to secure public safety, defend the nation and maintain order. Within a week of the Act coming into force, more than 100 new measures had been introduced. Split into several sections, they were known collectively as the Defence Regulations.3,4

Most of these wide-ranging measures were covered by the Defence (General) Regulations, though others with narrower, specific objectives were separately introduced. ‘Headline’ uses included the call-up of military reservists and the mobilisation of Air Raid Precautions (ARP) volunteers. A number of Defence Regulations, designed principally to prevent spying activity and interference with essential services, imposed a series of restrictions on the civilian population. It was alleged breaches of these that would first bring Dorothy O’Grady to the attention of the military and civilian authorities in the summer of 1940.

Once they had taken a rather more serious view of her activities, following the three weeks O’Grady spent on the run from justice, the Crown prosecutors added more sinister-sounding counts to an expanding sheet that would eventually run to nine charges. Now believing that she had not merely trespassed on the forbidden foreshore but had acted in a manner prejudicial to the interests of the State and carried out specific acts which threatened national security, the Crown was able to look to the Official Secrets Act of 1911 to aid its prosecution.

However, although she was prosecuted for breaches of both the Defence Regulations and Official Secrets Act, it was the capital charges she faced under the Treachery Act of 1940 that very nearly took the Isle of Wight landlady to the gallows.

The Treachery Act became law on 23 May 1940, thirteen days after Winston Churchill succeeded the disillusioned Chamberlain as prime minister and four days before the first Allied soldiers would miraculously escape the horrors of Dunkirk. With the enemy at the door – or very close to it – and soon planning to break it down via cross-Channel invasion, the Act was a timely, tough new measure to safeguard national security by the capture and prosecution of enemy agents.

Unlike the requirements for the Treason Act of 1351 (which still applied in 1940 and would be employed successfully five years later to convict the infamous Nazi broadcaster William Joyce, Lord Haw-Haw), prosecutions brought under the Treachery Act had no need to establish whether a defendant owed allegiance to the Head of State in order to find him or her guilty. To secure a conviction, it was sufficient only to show that he or she ‘with intent to help the enemy … does, or attempts, or conspires with any other person, to do, any act which is designed or likely to give assistance to the naval, military or air operations of the enemy, to impede such operations of His Majesty’s forces, or to endanger life.’

This somewhat convoluted definition of the 1940 Act’s scope and purpose was at odds with the simplicity of outcome for anyone convicted under its terms. The mandatory sentence in all cases was death. Dorothy O’Grady was the first Briton of either sex to be condemned to death under the Treachery Act. Had her February 1941 appeal not saved her from the gallows, she would have been the only woman of any nationality to suffer death under the Act during the Second World War – indeed, the only woman executed in Britain for spying in the entire twentieth century.

Seventeen men did suffer that fate between December 1940, the month of O’Grady’s trial in Winchester, and January 1946, the year after the war’s conclusion. Most stood trial under the Treachery Act before a judge and jury at the Old Bailey, though two were convicted by military courts martial. All but one were hanged in London prisons – either at Pentonville or Wandsworth. The single exception was Josef Jakobs (43), whose spying mission in England had ended before it had a chance to begin when he parachuted from the aircraft that had brought him from Holland, broke an ankle on landing and was quickly captured by the local Home Guard near Ramsey in the wilds of Huntingdonshire. Tried by court martial, he was sentenced to a military execution. On 15 August 1941 he became the last of the many people across the centuries to suffer execution at the Tower of London when he was shot by a firing squad in the miniature rifle range. It is a distinction he seems destined to retain.

As with the Jakobs case, the majority of convicted enemy agents executed in Britain during the Second World War were foreign nationals. The handful of British subjects who met the same fate were all tried for espionage activity carried out abroad. Had Dorothy O’Grady’s appeal failed, she would have been the only Briton executed during the war for treachery committed within the UK.

Newcastle-born marine engineer George Armstrong (39), hanged at Wandsworth in July 1941, was convicted on evidence that, while in the USA with his merchant ship during November 1940, he wrote to the German Consul in Boston, Massachusetts, offering his services, information and assistance to the enemy. A convicted con man, Armstrong’s later claim that he had done so in an attempt to expose a pro-German spying network in the States failed to save his life.

Merchant seaman Duncan Scott-Ford, from Plymouth, was hanged at Wandsworth in November 1942 for supplying secret information to Germany on vital shipping convoy movements between Britain and Portugal – not his first espionage mission in the enemy’s interests. Initially paid for his treachery, he was subsequently blackmailed in Lisbon by agents of the Nazis, whose threats to expose him to the British authorities forced his continued compliance with their demands. The highly impressionable Scott-Ford, who had earlier been dismissed from the Royal Navy at a court martial and served six months in prison for forgery and embezzlement, was just 21 at the time of his execution.

London-born Theodore Schurch (whose father was Swiss) became the last enemy agent to suffer execution when he was hanged at Pentonville in January 1946. Schurch was cajoled into enlisting with the British armed forces by Italian fascists before the war with the express purpose of passing militarily sensitive information to his Italian spymasters. He became an effective agent for Italy in the Middle East during the early years of the war. Allowing himself to be captured by the Germans at the Libyan port of Tobruk in June 1942, he resumed contact with Italian intelligence. Schurch spent the best part of the next three years seeking out information for Italy and then the German SS – notably from British prisoners of war – before his treachery ran its course in March 1945 when he was arrested by the Americans in Rome. At his court martial in London, Schurch (27) was found guilty of both treachery and desertion.

The fourth convicted traitor with British citizenship, thanks to his birth in Gibraltar thirty-four years earlier, was Jose Key, who was hanged at Wandsworth in July 1942 after a search on the Rock revealed him to be in possession of sensitive military information. Key, it was later proven, was planning to transmit this to the enemy.

Oswald Job, some of whose treachery did take place in the UK, was the only other British-born Nazi agent among the seventeen executed men. However, although he started life in London and was educated at an English public school, both his parents were German. Job’s route to the gallows at Pentonville in March 1944 began when he was interned by the Germans in occupied France because of his British passport. Managing to convince the occupying force of his German credentials, he returned to Britain via Spain. Having aroused suspicions in the UK, Job’s fate was sealed with the discovery of invisible ink crystals, cipher material and other spying paraphernalia which he had concealed within a large bunch of hollowed keys and in the handle of his safety razor. At 59, Oswald Job was the oldest of the seventeen men to suffer the death penalty under the Treachery Act.

So far, as female involvement in pro-Nazi espionage activity on British soil is concerned, the star billing in the Second World War undoubtedly belonged to the vivacious and enduringly mysterious Vera Schalburg – despite the fact that her spying mission in the UK appears to have been an abject failure. Better remembered in Britain as Vera Eriksson, the Danish alias she was using at the time, Schalburg arrived in September 1940 with two male colleagues in the north-east of Scotland. The trio’s planned journey south for spying roles in London was thwarted by speedy capture – a fitting end for a shambolic, ill-planned mission. The three agents’ subsequent arrest, the trial and execution of the two men, Vera’s escape from justice and the mystery of her ultimate fate have fascinated historians for decades. The release in recent years of wartime MI5 files relating to the woman dubbed ‘the beautiful spy’ threw considerable light on her background and involvement with Nazi Germany, but questions remain.

The very fact that so much of the mystery and argument over this fascinating Russian-born woman continues to this day means that, in this respect at least, her story has a parallel in the O’Grady case. In fact, there are further similarities between the two, although coincidences might seem the more appropriate term considering the vastly different circumstances that provide the bulk of the background to their life stories. Like Vera Schalburg, Dorothy O’Grady was adopted as an infant (see Chapter 8) and only a matter of weeks separated their respective police arrests in the early autumn of 1940. But could there be a real link?

It may seem fanciful to suggest a closer association between the two women, but there is both firm evidence and apparently well-founded theory to support the notion that there might have been. Historical fact can place them under the same roof on at least two occasions during the war and, amazingly, there is a suggestion that they might also have lived as near neighbours, relatively speaking, in the years after the war – on the Isle of Wight. Whatever the underlying truth, it is at least a remarkable coincidence that the island should be linked, however tenuously in the case of Schalburg, to both of these leading female characters in the annals of German spying folklore of the Second World War.

The possible link between Schalburg and O’Grady may be regarded as the stuff of whimsy but it is nonetheless worthy of closer scrutiny. It is examined fully in later chapters.5

Schalburg and her companions were caught out by inadequate preparation and inefficient implementation – not, it would seem, by any secret intelligence that warned MI5 in advance of their mission in Britain. The deservedly well-documented success of the Security Service (MI5’s official title since 1931) in uncovering supposedly covert enemy agents did not blossom until 1941. MI5 then became so adept at this that it was able to turn most of the spies sent to Britain by Germany against their former Nazi spymasters and the Third Reich as a whole. So successful was Britain’s famous Double-Cross System that J.C. Masterman, who chaired the committee in charge of it, felt able to conclude that ‘we actively ran and controlled the German espionage system in this country’.6

MI5 files released in recent years to Britain’s National Archives confirmed that the extraordinary success of the Double-Cross System was achieved via a combination of counter-espionage work before the war and signals intelligence during it. The Security Service was able to monitor the deployment of German agents and, consequently, pick them up more or less on their arrival in the UK. If they couldn’t be ‘turned’ – as was evidently the case with Vera Schalburg’s two male colleagues – they faced the unpalatable consequences of trial and a mandatory death sentence under the Treachery Act. The vast majority became double agents.

The pressure on them to turn against their German controllers was intense. Following capture, the agents faced interrogation at Latchmere House on Ham Common in south London, the formidable, specially adapted MI5 detention centre known in wartime as Camp 020. In all, 480 people were interned there for periods during the Second World War. Nazi agents arriving from occupied Europe provided the principal source of ‘raw material’ for MI5’s interrogators but there were others – suspected of either working for German interests or harbouring sympathies for the enemy – who passed through the less than welcoming doors of Camp 020.7

There is no doubt that MI5 took a keen interest in Dorothy O’Grady after her military arrest and subsequent dash from justice in August 1940. They could hardly have done otherwise. Why had she run away? Until then, however, there is no evidence to suggest that she had roused the suspicions of the Security Service.

Did she harbour fascist sympathies? Most Britons who did were either interned in the UK during the war or – in the cases of those who were the most committed to Hitlerian doctrine and, more often than not, were rabid anti-Semitists – had got out of the country in time to spend the war years in Germany or elsewhere, broadcasting propaganda or actively pursuing other work in the enemy’s cause. O’Grady, of course, was imprisoned rather than interned and her war effort for the enemy – if it truly existed – was wholly on British shores. There is some evidence, entirely self-professed, that she may have been an admirer of Hitler, but this has usually been dismissed – as eventually it was by her – as nothing more than a further extension of fantasy or delusion.

Despite the unprecedented success it would later achieve, the Security Service had begun the war in a state of near-chaos. It was understaffed and unprepared for the huge increase in its workload brought about by the need to respond to the avalanche of requests for vetting people suspected of posing a threat to the nation’s security. The demand was exacerbated by the mood of a nervous nation.

Treachery was everywhere in the early part of the war. That, at least, was the perception of a jittery British public. Suspicion among the populace suited a government anxious to avoid sensitive information reaching the ears of the enemy. Striking posters from the Ministry of Information hammered home the dire consequences of ‘careless talk’ and would soon be reminding would-be blabbers to ‘keep it under your hat’ – but just about anyone who seemed, in appearance, background or behaviour, to be out of the ordinary stood the risk of being seen as a potential traitor or spy. The sinister term ‘fifth columnist’ had entered the language.

In the Second World War, fifth columnist became a ‘catch all’ phrase for Nazi agents and collaborators secretly carrying out subversive operations in targeted nations. It had originated a few years earlier during the Spanish Civil War – specifically the October 1936 Siege of Madrid by four columns of Nationalist troops under the command of General Emilio Mola. In the course of a broadcast for a rebel radio station, the general trumpeted that he would be able to call on additional supporters hiding within the city to reinforce the Fascist cause. It remains a matter of debate whether it was Mola himself or, more likely, the US press reporting the war who first tagged this shadowy force the fifth column. Mola’s move on the Spanish capital failed and the following June he was killed in a plane crash. But the fifth column was set to transcend the Civil War.

There was a widely held belief that the Germans’ lightning advance across western Europe in 1940 could not possibly have been achieved without some form of organised, embedded support for the Nazi forces within the nations that successively capitulated to the might of Hitler’s stunning Blitzkrieg offensive. And, ran the near-hysterical argument in Britain, if a fifth column had existed in Scandinavia, the Low Countries and France, then why not here in the UK as well?