Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

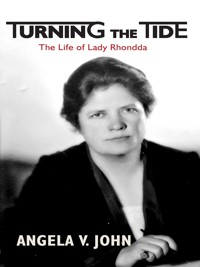

This rich biography tells the remarkable tale of Margaret Haig Thomas who became the Second Viscountess Rhondda. She was a Welsh suffragette, held important posts during the First World War and survived the sinking of the Lusitania. A leading British industrialist, she was also instrumental in securing a seat for women in the House of Lords. Closely associated with figures such as Winifred Holtby, Vera Brittain and George Bernard Shaw, she founded and edited the weekly paper Time and Tide, which dazzled British society with its cutting-edge perspectives. It championed progressive views on women's rights in the 1920s, became a leading literary space for women and men from the thirties onwards and a respected political commentator on national and international affairs. Drawing upon a rich array of sources, many previously unused, Angela V. John explores both the public achievements and the fascinating private world of one of the movers and shakers of British society in the first half of the twentieth century.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 814

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Acknowledgements

List of Abbreviations

Lady Rhondda’s Life

Introduction: Looking for Lady Rhondda

1. Margaret Haig Thomas

2. Mrs Mackworth: Marriage and Suffrage

3. ‘To Prison while the Sun Shines’

4. Survival: the Lusitania

5. War Service

6. Responsibility and Reputation

7. Being D.A.’s Daughter

8. ‘Quite a different place’: Reconstructing the Public and the Private

9. ‘The Queen of Commerce’

10. Time and Tide: The First Two Decades

11. A Woman-Centred World

12. Pointing the Way: the Six Point Group and Equal Rights

13. Reading Lady Rhondda

14. Entitlement: Viscountess Rhondda and the House of Lords

15. Friends and Foes: Politics and War

16. The Wrong Side of Time

Postscript: Later

Appendix

Notes

Illustrations

Copyright

TURNING THE TIDE

The Life of Lady Rhondda

Angela V. John

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

At an early stage in my research I spent a summer’s afternoon with the historian Ryland Wallace exploring the village of Llanwern in south-east Wales. This was where the Thomas family had lived. A chance meeting with helpful local resident Sharon Burgess proved to be a catalyst for much more. It led to interviews with Coral Westcott and the late Barbara Hollingdale, both very knowledgeable about the area and the family. Through them I got to know descendants on Margaret’s mother’s side and descendants of D.A. Thomas, her father.

I have been aided immensely by these family members. One of my greatest debts is to Frankie Webber, Margaret’s god-daughter and cousin who also worked forTime and Tide.Her reminiscences in numerous letters and telephone conversations, and her welcome in Ireland have helped to transform my understanding. Anne Eliza Cottington has been wonderfully supportive and generous, and has given me access to sources as well as introducing me to Pen Ithon Hall and the wider family. Rosie Humphreys and Clare Davis have kindly let me use family papers and provided valuable insights for which I am also much indebted. Jamie Cottington’s expertise has been especially valuable. I am also very grateful to Susannah Bower and Nicholas Wightwick. Ann Salusbury has illuminated several puzzles. Thanks also to Daisy Greenwell, Astrid Treherne and Mrs R.P.D. Treharne for their correspondence.

I have received great kindness and assistance from those living in Margaret’s former homes. John Knight and his family could not have been more welcoming. The same goes for Angela and Hugh Ellingham. I’m also grateful to Ian and June Burge and Peter Collacott. Others have been generous with written material. Deirdre Macpherson has kindly shared her research on the Archdale family. Paula Bartley, Ellen Wilkinson’s new biographer has, as always, willingly provided me with information. The Winifred Holtby scholar Gill Fildes has been ever ready to supply references, and discussions with her have aided me greatly.

At the Palace of Westminster, Baroness Gale of Blaenrhondda, Mari Takayanagi, Jessica Morden, Melanie Unwin and Dorothy Leys have been very helpful. I am indebted also to Anthony Lejeune and Catherine Gladstone for their memories ofTime and Tideand to Catherine Clay, author of a forthcoming literary study of the paper. Denise Myers has kindly shared material on Llanwern and Gerard Charmley on D.A. Thomas. Richard Clark was most helpful. Ryland Wallace helped to kickstart much research and he and Lucy Bland read draft material. I am grateful to Richard Keen for accompanying me on research trips from Donegal to New York.

Although it is not possible to name all who have contributed in some way, I wish to mention the following: Jane Aaron, Deirdre Beddoe, David Berguer, Katherine Bradley, Handa Bray, Laurence Clark, Sioned Davies, Martin Durham, Shirley Eoff, Neil Evans, Hywel Francis, Emelyne Gordon, Lesley Hall, Nicholas Hiley, Carolyn Jacob, Simon James, Aled Jones, Elin Jones, Julia Jones, Louise Knight, Thomas Lloyd, Ceridwen Lloyd Morgan, Mair Morris, Peter Mountfield, Nicole Phillips, June Purvis, Imogen and Steve Roderick, Jenny Rudge, Marion Shaw, Michael Sherborne, Angela Tawse, Pam Thurschwell, Norman Watson, Chris Williams, Emma Williams, Huw Williams, Sian Williams and Judith P. Zinsser.

I am grateful to the archivists/librarians of Aberystwyth University; the BBC Written Archives Centre, Caversham Park, Reading; Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford (Department of Special Collections); Bristol Record Office; British Library; British Library of Political and Economic Science (Archives Division); CADW; Cardiff University Archives; Columbia University in the City of New York (Rare Book and Manuscript Library); PEN International; Eton College Archives; Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University; Gwent Record Office; Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin; HMCS (York Probate – Sub Registry); Houghton Library, Harvard University; Hull History Centre; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (The Rare Book and Manuscript Library); Imperial War Museum; Mary Evans Picture Library; McMaster University (William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections); Merthyr Tydfil Central Library; The National Archives, Kew; National Portrait Gallery, London; The National Trust (Records and Archives, Heelis, Swindon); Newport (Gwent) Museum and Art Gallery; Newport (Gwent) Reference Library; New South Wales State Library; the Palace of Westminster Collection; The Parliamentary Archives; University of Reading Special Collections Service; Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University; Somerville College Library, University of Oxford (and the Principal and Fellows of Somerville College); Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales; South Wales Miners’ Library, Swansea University; SPR Archives, Cambridge University Library; St Leonards School Archives; Surrey History Centre; University of Sussex; West Glamorgan Archives and the Women’s Library, now the Women’s Library @LSE.

Special mention must be made of Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/National Library of Wales for the unfailing helpfulness and friendliness of staff, from those who hauled heavy volumes ofTime and Tideweek after week, to individuals who provided all sorts of advice and expertise.

I have benefited from the opportunity to try out some of my ideas at the following: Ursula Masson annual memorial lecture, University of Glamorgan 2011; the House of Lords; the annual Women’s History Network lecture at the Women’s Library, London 2012; the Women’s History Network Conference, Cardiff University; the PENfro BookFestival; Port Talbot Historical Society; ‘The Aftermath of Suffrage’, International Conference, Humanities Research Institute, University of Sheffield and the NAASWCH Conference, Bangor University.

Every effort has been made to contact copyholders. I thank the Society of Authors (on behalf of the Bernard Shaw Estate and as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf), the Michael Ayrton Estate (Henry W. Nevinson and Evelyn Sharp Papers), the British Library (Phyllis Deakin recording), Hull City Council (Winifred Holtby), Independent Age, formerly RUKBA (Elizabeth Robins Papers). Quotations from published and unpublished Vera Brittain material are included by permission of Mark Bostridge and T.J. Brittain-Catlin, Literary Executors for the Estate of Vera Brittain 1970. The quotation from Glyn Jones is by permission of the copyright holder Literature Wales. The verse from John Betjeman’s poem ‘Caprice’ is reproduced by permission of John Murray (publishers).

I was fortunate to be given an Authors’ Foundation grant by the Society of Authors which enabled me to carry out research at Harvard and New York Universities and, like many writers, have received excellent advice from this society. A Small Literary Commission Grant by the Welsh Books Council helped me to complete research within the UK.

I have benefited from the wisdom and expertise of my editor Francesca Rhydderch. Working with the Parthian team has been a delight and I thank all involved, especially Richard Davies.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

BFUWBritish Federation of University Women

CCWOConsultative Committee of Women’s Organisations

D.A.David Alfred Thomas, Viscount Rhondda

EPRCC/ERGECCEqual Political Rights Campaign Committee/Equal Rights General Election Campaign Committee

ILPIndependent Labour Party

NSDNational Service Department

NUSECNational Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship

NWPNational Woman’s Party

NUWSSNational Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies

SPGSix Point Group

SPRSociety for Psychical Research

WAAC/QMAACWomen’s Army Auxiliary Corps/Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps

WILWomen’s Industrial League

WRAFWomen’s Royal Air Force

WRNSWomen’s Royal Naval Service

WSPUWomen’s Social and Political Union

LADY RHONDDA’S LIFE

1883Born in London

1887Moves to Wales. Lives at Llanwern House, Monmouthshire

1899To Boarding School in Scotland

1904To Oxford University

1908Marries Humphrey Mackworth

1909Secretary of Newport, Monmouthshire’s suffragette society (till 1914)

1913Arrested and briefly imprisoned in Usk Gaol

1914Becomes Lady Mackworth

1915Survives the sinking of theLusitania

1917Women’s National Service Department Commissioner for Wales

1918Chief Controller of women’s recruitment in Ministry of National Service

On death of father becomes the second Viscountess Rhondda

Founds Women’s Industrial League

1919By now Director of 33 companies

1920EstablishesTime and Tidein London

1921Founds Six Point Group

Publishes memoir of father

1922Rhondda Peerage Claim is accepted then rejected

Meets Winifred Holtby and Vera Brittain

1923Divorces

1925Moves to Stonepitts, Kent with Helen Archdale

1926Becomes editor ofTime and Tide

Elected first female President of the Institute of Directors

Chairs equal rights societies (from 1926-8)

1933Publishes autobiography

1937Moves to Churt Halewell, Surrey with Theodora Bosanquet

Publishes book of essays

1943President of Women’s Press Club

1943-5WritesTime and Tidepamphlets

1955Receives honorary doctorate from the University of Wales

1958Dies in London

INTRODUCTION

Looking for Lady Rhondda

Margaret Haig Thomas, who became the Second Viscountess Rhondda in 1918, was one of the movers and shakers of British society during the first half of the twentieth century. She is probably best remembered for having founded, funded and editedTime and Tide,an innovative, imaginative and adaptable weekly paper that dazzled readers with its cutting edge perspectives. From its start in 1920 until her death almost four decades later she was at its helm, helping to shape this mouthpiece for the intelligentsia. It described itself as ‘the paper which is trying not merely to talk but to think’.1

Although never written exclusively by or for women, its pioneering all-female board and the serious attention it paid to women’s rights gave newly enfranchised women in particular a voice and a confidence. When asked what inspired her feminism, the journalist Mary Stott explained that she ‘ingested it from theManchester GuardianandTime and Tide.2By the 1930s it had transmuted into a Bloomsbury-based literary journal showcasing the emerging and leading writers of the day, including Sean O’Casey, Rebecca West, D.H. Lawrence and Rose Macaulay. After the publication ofThe Yearsin 1937, Virginia Woolf wrote of her relief – not only was her book praised by theTimes Literary Supplementbut also ‘Time and Tidesays I’m a first rate novelist and a great lyrical poet’.3By 1945 the paper had reinvented itself once more as a leading political review.

For this vision and enterprise alone, overseeing what Anthony Lejeune has called ‘this stupendous ocean of ink’,4and refusing to toe official lines, Margaret deserves recognition. Yet her achievements did not start or end there. She had gained notoriety in pre-war Wales as a suffragette. She was the long-term secretary of the Newport branch of the militant Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). In 1913 she was briefly imprisoned and went on hunger strike. She was not, however, the classic rebel woman reacting against a narrow Victorian upbringing. Although her eminently quotable autobiography tells how women’s suffrage was ‘the very salt of life’ and came ‘like a draught of fresh air into our padded, stifled lives’,5in truth she had been much less stifled than most women.

Margaret’s remarkable family included redoubtable figures on her mother’s side: female Haig relatives who were already deeply committed to suffrage activism. Her father, the industrialist and Liberal politician David Alfred Thomas (known as D.A.) became internationally renowned as a highly successful and wealthy industrialist. He was Margaret’s sounding board and she was devoted to him. She had been to university (briefly) and although her decision to marry Humphrey Mackworth, a local country squire, was a recipe for restlessness, she had greater latitude than many of her contemporaries and pursued a career in business.

The bond between Margaret and her father was cemented by the terrifying ordeal they endured in 1915 when they both survived – just – the sinking of theLusitania.D.A.’s premature death three years later had huge repercussions. It meant that Margaret inherited his business empire, his title and responsibility for his natural children. The story of D.A.’s parallel family forms an important and intriguing part of his legacy and Margaret’s life, yet until now it has been missing from historical accounts of both figures.

In contrast, Margaret’s career as an industrialist was widely recognised at the time. In 1927 theNew York Tribunecalled her ‘the foremost woman of business in the British Empire’.6Inheriting her father’s coalmining, shipping, newspaper and other interests made her a very wealthy woman. By 1919 she was sitting on 33 boards and chairing seven of them. She held more directorships than any other woman in the UK in the 1920s and in 1926 became the first and, to date only, female president of the Institute of Directors. TheDaily Heralddescribed her as one of the five most influential individuals in British ‘Big Business’.7But she had to learn to operate in an overwhelmingly masculine environment that was wary of female entrepreneurs. And the timing was disastrous. Her father’s fortunes had been made in heavy industry. The depression and long-term decline in the demand for coal posed new challenges.

Margaret had held weighty posts during the First World War, first in Cardiff, then London, where she was chief controller of women’s service within the Ministry of National Service. In 1921 she founded and chaired the Six Point Group (SPG), which sought to complement women’s newly-won political emancipation with equal social and legal rights. Through this group she promoted equal rights in Europe. Her involvement in international feminist politics in the 1920s included publicly endorsing at home and abroad the views of the militant American National Woman’s Party.

In the 1920s she was one of the leading figures in the battle for women under thirty to receive the vote. This important yet neglected final piece of the women’s suffrage jigsaw receives due attention here. At the same time she became embroiled in a sustained and inventive battle for hereditary peeresses to take their seats in the House of Lords. Tenacious to the last, she persisted in her claim for forty years and was largely responsible for their belated victory.

To date much that has been written about Margaret Rhondda has understandably focused on her as an important equal rights figure in Britain. Dale Spender’s volume of extracts fromTime and Tideconcentrates on the 1920s, telling the feminist part of the story of Margaret’s paper.8The subtitle of American historian Shirley Eoff’s valuable 1991 study of Margaret isEqualitarian Feminist. She explained that her intention was not to present a complete biography but ‘to illuminate Lady Rhondda’s struggle for equal rights and social justice in modern Britain’.9In her account, the spotlight is firmly trained on the twenties and thirties.

Catherine Clay’sBritish Women Writers 1914-1945(2006) examines networks of friendship enjoyed by women writers. Margaret and her paper are writ large here.10But we need also to consider Margaret’s later years when she does not so easily fit the role of either feminist icon or non-party progressive. Her specific focus on women’s rights had receded by the late 1940s and 1950s and her political outlook shifted to the right.

Clay does, however, help to redirect us to some of Margaret’s significant friendships, most notably that with Winifred Holtby, who becameTide and Tide’syoungest director and was an invaluable member of the writing staff until her tragically early death in 1935. In Holtby’s most famous novelSouth Ridingher headmistress heroine Sarah Burton has her senior girls read Lady Rhondda’s autobiographyThis Was My Worldas their Easter holiday homework.11Holtby’s life – and death – is important for understanding Margaret. Vera Brittain’s name has long been associated with Holtby and she too played a significant part in Margaret’s story but in a markedly different way.

George Bernard Shaw was another key figure in Margaret’s life. She enjoyed socialising with him and they sustained a fond and frank correspondence. HisTime and Tidearticles were much appreciated. Margaret’s many contributions to her paper included thoughtful critiques of Shaw’s plays. Much less forgiving were her attacks on the writings of H.G. Wells, who could not be called a friend.

Margaret was divorced in 1923. She had moved from Wales to London and made a home in Kent. She lived first with Helen Archdale, who editedTime and Tidein its early days, then spent the last twenty-five years of her life in London and Surrey with Theodora Bosanquet. Theodora12became the paper’s literary editor. She had been Henry James’s amanuensis and this and her own writing have recently received attention. She knew James’s biographer Leon Edel and features not only in his work but also, for example, in David Lodge’sAuthor, Author.13

Margaret was the subject of a poem by her disgruntled employee the poet John Betjeman and appears in an unpublished play by Holtby. She features prominently inClash, a novel about the General Strike of 1926 by the socialist politician Ellen Wilkinson.14The two women were good friends. Wilkinson’s character is a wealthy but compassionate socialite. Margaret spent much of her life challenging the belief that being rich connoted idleness. She worked hard and spoke and wrote about the problems of ‘The Leisured Woman’, but her love of luxury and appetite for travel also undermined her assertions when so many were living in poverty.

A study of Margaret’s long life needs to consider what Wales meant to her. She spent her formative years at Llanwern in south-east Wales and at Pen Ithon Hall (her mother’s family home) in mid-Wales. Her father’s and (subsequently) her own wealth came from the south Wales valleys. In later years she re-engaged with her Welsh roots, not least through an increased attention to questions of Welsh identity in the columns ofTime and Tide.

Although Margaret’s achievements were largely unsung in the second half of the twentieth century, there is now evidence of renewed interest in her life. In 2003-4 an online poll (with 41,223 nominations) to identify the top hundred Welsh heroes ‘of all time’ ranked her 66th.15The list contained a mere ten women and was led by Catherine Zeta Jones at number thirteen. Margaret was depicted as a groundbreaker and ‘The Welsh Boadicea’.16 The historian Deirdre Beddoe has pronounced her ‘without doubt the most prominent Welsh woman of the twentieth century’.17

When the Addidi Inspiration Award for Female Entrepreneurs was launched for UK businesswomen in 2009, Margaret was selected as one of the five nominees.18This wealth management group had decided to honour female entrepreneurs from a time when ‘it was not common for women to be running businesses and creating wealth’. Each nominee was championed by a modern successful businesswoman. Margaret’s was the online strategist Shaa Wasmund, who applauded her business acumen and desire to improve life for other women.

In line with my other biographies, Margaret’s life story is told here in a broadly chronological fashion but structured so that individual chapters examine specific interests. Some follow aspects of her public life. Others adopt a more personal focus. To aid the reader, the main events of her life are outlined on pp. 11-12.

The first three chapters examine Margaret’s years in Wales as a daughter, wife and suffragette. There follow three chapters on her war work and dramatic experiences, from the sinking of theLusitaniato a scandal concerning the Women’s Royal Air Force. The next two chapters show how she reconstructed her life in London after the war in personal and public terms following the death of her father and the consequent responsibilities she secretly had to shoulder.

Margaret was unusual in that she brought together the often divergent worlds of business and the arts. Chapter 9 follows her fortunes as a businesswoman, while Chapter 10 assesses the significance of the first two decades ofTime and Tide. Chapter 11 looks at her woman-centred social world, considering both how she was viewed by others and her personal relationships, including her friendship with Holtby. Margaret’s feminist politics at home and internationally are the focus of Chapter 12. An assessment of her writings follows in Chapter 13. Chapter 14 tells how she fought for a seat for women in the House of Lords. The last two decades of Margaret’s life and the shifting political and financial fortunes ofTime and Tideare explored in the final two chapters. They also consider the influence of Theodora Bosanquet and of the Second World War on Margaret and examine how she adjusted to the 1950s.

Biography can be deceptive. It supplies a rounded, composite figure, imposing a suspicious order and linear development on a life. It risks over-estimating the significance of an individual in her or his society. It is tempting to reduce the subject to hero or villain status, to provide worryingly neat solutions and so undervalue the protean nature of peoples’ motives and actions.19The wish to empathise or to provide a definitive account can encourage generalisations and a rejection of descriptions that do not fit our dominant, invariably subjective images. It can suggest impossibly consistent lives. In practice we are all prone to be contradictory and fickle, presenting varying faces to different – and even the same – people in the present, let alone over a long period of time. Appreciating how others view ‘our’ subject means recognising a parallax: understanding that perspectives can shift, depending on audience, circumstances, experiences and personal predilections.

Statements that might at first appear contradictory can, however, be usefully reconciled rather than refuted. They can help to reveal aspects of the multiple identities individuals both construct and have constructed for them. Even basic descriptions of physical appearance can vary enormously. In 1922 the American press described Margaret as ‘a rather magnificently big and sturdy looking woman’.20The explorer Freya Stark remembered first meeting her at lunch with the archaeologist Gertrude Caton-Thompson in 1936. Stark saw her as ‘a powerful person with a really beautiful face, with kind and amused mouth and strong broad forehead and square hands – all square and small and strong she is’.21The journalist Malcolm Muggeridge, who contributed toTime and Tide, recalled Margaret as ‘plump and curly’.22Such apparently contradictory comments are revealing about time and the person who made them, but memory, gender, culture, environment, potential readers and even fashions in hairstyle (Margaret had her hair shingled) also helped to influence and inflect such perceptions.

This biography includes a number of visual representations of Margaret. These photographs and paintings suggest change over time and her catholicity of interests. We can track the young schoolgirl at St Leonards, watch her engage in street politics as a suffragette in 1913 and contrast this with Solomon J. Solomon’s portrait of the elegant young lady. We see Margaret turn into the reflective businesswoman-cum-journalist in Hoppé’s photograph. The international campaigner is captured as she meets the American Alice Paul in London with other members of the International Advisory Committee of the National Woman’s Party in 1925. A formal portrait painted by Alice Burton six years later reveals a dignified woman, carefully dressed and displaying the turquoise-and-diamond brooch, set in gold, that her mother had given her. Margaret still wears her wedding ring here (and would continue to do so) although she had been divorced for almost a decade.

But just as representative, albeit less stately, is an informal snap of Margaret in the garden of her Surrey home, Churt Halewell. Here she is casually dressed in corduroy trousers and a cashmere sweater bought for her by cousins after she had treated them to a skiing holiday. An image of an older, somewhat weary-looking Margaret standing on the steps of the Bloomsbury offices ofTime and Tidereminds us of her final years. After decades of propping up her paper, the money began to run out, the venture to which she had dedicated much of her life was threatened and her health gave way.

The various names Margaret used are indicative of the different roles she played. Young Margaret Haig Thomas was known to her cousins as Daisy (Marguerite) but to the villagers of Llanwern she was ‘Her Young Ladyship’. When she married she became Mrs Mackworth and then Lady Mackworth but these marks of her marriage were left behind in 1918 when she inherited her father’s title and became the second Viscountess Rhondda. Too often in pictures and print she was (and remains) confused with her mother Sybil Margaret, the Dowager Viscountess. Formal communications were signed ‘Rhondda’ but MR or Margaret was how she ended letters to her friends.

Letters form an important part of this biography, whether correspondence with Holtby or those in whichTime and Tidecontributors such as Brittain and St John Ervine discuss Margaret. Then there are sensitive family letters, including Margaret’s correspondence with D.A.’s mistress and children and some heartrending personal letters to Helen Archdale. Inevitably there are also some tantalising gaps. For example, Humphrey Mackworth remains a shadowy figure due to a lack of written material. We may speculate but there is no reliable explanation as to why Margaret and Humphrey did not have children. Mere scraps of evidence alert us to what he might have felt about his wife’s activities and there is no record of how he reacted to herLusitaniaordeal.

D.A.’s papers in the National Library of Wales contain two large scrapbooks of press cuttings about Margaret. Although she left no diary,23two volumes written in the thirties by her mother Sybil have been discovered recently. Valuable perspectives can also be gleaned from the diaries of the former actress and suffragette Elizabeth Robins, a founder member of the board ofTime and Tideand of the SPG. Theodora also kept a diary and we can glimpse the last fifteen years of Margaret’s life refracted through her entries.24

Time and Tideitself has been central to this project. Margaret wrote hundreds of articles, many for her paper, and several books. Her autobiography, published as early as 1933, has been used by historians and literary critics. But it is a misleading, albeit fascinating, source, as significant for what it conceals as for what it discloses about her past, let alone her present. Other ‘ego documents’ survive, such as an unpublished autobiography by Helen Archdale as well as specialist collections that throw light on Margaret’s war work, business dealings, radio broadcasts and much more. Oral testimony has been especially helpful, particularly that of Margaret’s god-daughter and relative Frankie Webber who also worked forTime and Tide.

Biography may pose some problems but when such rich sources are considered, its potential far outweighs them. Indeed, the biographer occupies a crucial vantage point, since only with time and distance can the broad patterns of a life be effectively traced. Biography is also increasingly appreciated for what Barbara Caine has recently described as ‘the capacity of an individual life to reflect broad historical change’.25Exploring the life of a pivotal twentieth-century figure such as Lady Rhondda can make this possible.

CHAPTER ONE

Margaret Haig Thomas

In a quiet country lane on the edge of the little Welsh village of Llanwern in Gwent, there is a church dedicated to St. Mary. A tall memorial stone with a pedestal is prominent in the churchyard. It commemorates the lives of three people. The first is David Alfred Thomas, Viscount Rhondda of Llanwern (1856-1918), privy councillor, MP for 22 years, president of the Local Government Board and Food Controller in the Great War. ‘He counted not his life dear unto Himself’ is his epitaph. ‘Blessed are the pure in heart’ are the words chosen for his wife Sybil Margaret (née Haig, 1857-1941).

The ashes of their only child, Margaret, are also buried here. She is described as ‘Proprietor and Editor of Time and Tide for 31 years’ and a simple ‘Rest in Peace’ follows. Itisa peaceful setting, although from the 1960s the Spencer Works, Britain’s first wholly oxygen-blown integrated steelworks, would dominate the landscape. Yet this was an appropriate legacy for a family whose wealth had been based on heavy industry.

Across the fields from the church stood Llanwern House. Here the Thomas family lived from the end of 1887. Although Margaret claimed that it was built in William and Mary’s reign, later stating that it was a Queen Anne building, it was probably constructed in or soon after 1760 on the site of an older house.1Demolished in the early 1950s, the three-storey building enjoyed a commanding position on a hilltop about 200 feet above sea level and overlooking what is known as the Caldicot Levels. On a clear day it was possible to look across the Channel to Clifton Suspension Bridge.

Llanwern Park’s two hundred acres of rolling land were covered with elm, beech and lime trees. There was an Italian sunken garden, lily pond, fan garden and underground ice house as well as a large walled kitchen garden. The rectangular, slightly austere, pale red-brick house with a stone parapet was at the end of a long winding drive and seemed less attractive than the landscape. The lack of ornamentation gave it a somewhat utilitarian appearance and it was readily dismissed by one French governess as ‘[more] like a factory than a house’.2Yet one side boasted a vast flowering magnolia, reputed to be the tallest in Britain. A gardener travelled from Kew Gardens just to prune it. Large elms helped to screen the building from view. It faced west and when the setting sun was reflected in its many windows the house looked as though it were on fire.

It was just a few miles from Caerleon and Newport and convenient for D.A. Thomas – D.A. – to travel by train to his office in Cardiff. And although the London train was not scheduled to stop at Llanwern station, it did so for the Thomas family. At first Llanwern Park was rented but D.A. purchased it in 1903 and the interior of the house was restored to its former splendour by Oswald Milne, assistant to the great architect Lutyens.3It had large, somewhat formal rooms with elaborate plasterwork and a few Chinese features.4Llanwern is close to Magor where D.A.’s grandfather had been a yeoman farmer before moving to work in the Merthyr pits. Llanwern (the church in the alders or, less romantically, the church on swampy land) was where Margaret grew up.

Both of her parents had a huge influence on her as a child and adult. D.A.’s decision to involve his daughter in his business empire and to hand his title to her says a lot about him, though this was not as straightforward as the historical record suggests. Margaret’s book about her father exceeded three hundred pages and was slightly longer than her own autobiography. The latter appeared when she was fifty but reads as the account of a dutiful daughter. At the same time the contrast between her opportunities and those of her mother speaks volumes about the changes in early twentieth-century British society.

The life of Margaret’s mother, known as Mrs D.A. Thomas (later Dowager Viscountess Rhondda) seems, like her mode of address and the experiences of many Victorian women, to have been primarily defined through others. When she died in March 1941,The Timesobituary said little about her. Practically all the information was about whose widow she was and who her daughter Margaret had become. It was also pointed out that she was a member of an ancient Scottish Border family with an impressive lineage: the Haigs of Bemersyde in Berwickshire. The distinguished soldier and founder of the British Legion, Earl Haig, was a cousin. Sybil boasted seventy-two first cousins.

Here was an impressive extended family with a very long history proudly traced back to Petrus De Haga of the twelfth century. Its members knew – and still know and celebrate – their third and fourth cousins and have not infrequently married them. Haigs put family connections first. An acquaintance described the clannish family as ‘a regular maelstrom… if you entered into friendly relations with them you had to become a Haig’.5Margaret described her Haig relatives as the ‘endlessly ramified cousins’.6They were all part of the Haig ‘cousinage’. They would come ‘in shoals’7to stay at Llanwern – Sybil’s diary in the mid-1930s records cousins young and old – and throughout her life Margaret retained a loyalty to them.

Sybil had been born in Brighton on 25 February 1857,8the fourth daughter in a family of ten children that, like the offspring of Lady Charlotte Guest (who also married a wealthy Welsh industrialist) divided neatly into five boys and five girls.9Her father George Augustus Haig had been born and raised in Dublin. The son of a distiller, he became a successful agent in England for the sale of Scotch and Irish spirits and then set up his own business as a wine merchant in London, where he also owned property.

In 1858 he purchased 2,548 acres of land with eleven farms near the village of Llanbadarn Fynydd, between Llandrindod Wells and Newtown. Here, on gently sloping land in this beautiful hill country, he designed and had built in 1862, Pen Ithon Hall, named after the River Ithon. This two-storeyed house followed the Irish practice of having a central hall from which the main rooms radiated and, like his family home Roebuck, a front entrance with Doric columns in the Irish Georgian style.

George Augustus Haig became High Sheriff for the county as well as a magistrate. He stood (unsuccessfully) in several elections as a parliamentary candidate. Margaret’s grandmother Anne Eliza (née Anne Elizabeth Fell) was, she felt, gentle, humorous and rather more tolerant than her grandfather. She died when Margaret was eleven. The pretty lych-gate in the churchyard at the local church is dedicated to her memory. George Augustus Haig, who boasted luxuriant mutton-chop whiskers, lived on until 1906.

The daughters were artistic. Like her eldest sister Janet, Sybil painted miniatures and later exhibited some of her work in London galleries. One of her brothers, Alexander W. Haig, was a student at Cambridge in the late 1870s and friendly with two Welsh brothers, John Howard (Jack) and the younger David Alfred Thomas. Jack had visited Pen Ithon where he had met Rose Helen, Sybil’s elder sister. They became engaged and in the summer of 1880 Rose and Sybil, accompanied by Mrs Haig, visited Jack’s home, a stuccoed mansion called Ysgyborwen, outside Aberdare in Glamorgan. This was how Margaret’s parents met. Despite old Mr Haig’s reservations about D.A.’s credentials, he and Sybil were engaged in July 1881. D.A. was christened. On 27 June 1882 they were married by special licence in Pen Ithon’s billiard room.

D.A. had been born at Ysguborwen on 26 March 1856. His was an even larger family than his wife’s. He was the fifteenth of seventeen children born to Samuel Thomas and his second wife Rachel when she was eighteen and he was forty. Tragically only five of their children survived infancy (Samuel’s first wife and their child had also died young). As with her account of her Haig grandparents, Margaret’s depiction of the Thomas household plays on the contrast between husband and wife. She stresses her paternal grandmother’s sociability and generosity in contrast to her older, somewhat taciturn and stern husband. She tells how he once burned a new fur coat on which she had lavished sixty pounds – a huge expense in the late nineteenth century – without his permission.

According to Margaret, she then spent a further sixty pounds on another coat and said she would go on buying if need be. Samuel Thomas let her keep this coat.

Margaret was keen to paint a picture of a self-made man, a devoted nonconformist and strict disciplinarian. It helped to form a contrast to the idyllic life she sought to convey when describing her own upbringing as the sole child of loving parents. She nevertheless conceded that D.A. was proud of his father and was his favourite child. He followed in his footsteps. Samuel is reputed to have muttered on the day D.A. was born, ‘I see nothing for him but the workhouse’. Although highly conscious of the precariousness of building a fortune and reputation – Samuel was close to bankruptcy at the time of his son’s birth – he prospered. Originally a grocer in Merthyr Tydfil, he became a very successful mining entrepreneur and laid the basis for his granddaughter’s riches. Yet Sybil was seen as marrying beneath her. Ignoring the fact that it was D.A. who gave his wife her title, when interviewed an elderly former inhabitant of Llanwern village explained that: ‘Lady Rhondda wasLadyRhondda and the man she married was just D.A. Thomas’.

Margaret’s autobiography is somewhat dismissive of Rachel Thomas’s achievements. She conceded that her grandmother possessed ‘a good deal of artistic instinct’ but added that ‘she did not make very much impression upon me’. She portrayed her as charming but rather inconsequential and ‘though quite shrewd in her way, quite unintellectual… She was a kind and a nice woman, but never probably a very interesting one’.10

Yet this description is at odds with other evidence: Rachel Thomas was highly regarded in Welsh literary circles. She was a member of the Gorsedd11and her bardic name was Rahil Morganwg. She was active in the prestigious Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion and knowledgeable about genealogy. She was described in the press as the natural successor to Lady Llanover, the renowned patron and promoter of Welsh cultural life.12Widowed young, she then divided her time between Wales and England. She lived at the magnificent Blunsdon Abbey near Swindon with her daughter (Margaret’s cousin Louisa Mary) and spent the London season at their house off Park Lane. When she died in her seventy-third year in 1896, three special trains were laid on from Cardiff (via Pontypridd), Llwynypia and Merthyr to bring people to the public funeral in Aberdare. In his account of D.A.’s election as Merthyr’s MP in 1888, the former Liberal MP Llewelyn Williams suggested that her popularity in the constituency helped to ensure D.A.’s selection as a candidate.13Admittedly, Margaret was only twelve when Rachel Thomas died, but her portrayal is nonetheless skewed. It may reflect her desire to emphasise her father’s independent achievements, but it suggests too a lack of interest in Welsh-language culture.

At first Dai, as her father was then called, spoke only Welsh at home. A nurse from England taught him English. When he was nine he was sent to school at Manila Hall, Clifton. He spent a year abroad before reading mathematics at Cambridge University where his chief occupation seems to have been sports. Yet, unlike many of his fellow entrepreneurs, he was and remained fascinated by ideas and books throughout his life. It is interesting, though, in the light of his daughter’s truncated time at university, to see that although he initially won a scholarship to Jesus College, it was later taken from him because he did no work. However, he was suffering from ill-health and so took what today we would call a ‘gap year’, travelling abroad. A second scholarship was awarded at Gonville and Caius College. David Evans’s hagiographical memoir claims that D.A. was ‘one of the most promising mathematical scholars who ever left that great seat of learning’.14But he was awarded only a second class degree, of which he was ashamed.

D.A. started reading for the Bar, but once his father died in 1879 he turned his attention from the legal profession to the family business. He had inherited a personal fortune of £75,000, Ysguborwen Colliery and a share in the Cambrian Collieries. These Rhondda collieries were run by the firm Thomas, Riches & Co (J.O. Riches and O.H. Riches had been Samuel Thomas’s partners).

A new deed of partnership was drawn up. D.A. and his elder brother Jack (always the more conservative of the two and now married to Sybil’s sister) agreed to manage the collieries with the Riches brothers. D.A. worked in the sales department and then literally learned his trade at the coalface at Clydach Vale. Margaret’s account of her father’s life, which includes extracts from his letters, emphasises that he was more ambitious and ready for change than his three partners. After marrying Sybil in June 1882 and living for six months in Cardiff, they left Wales for London. According to Margaret, D.A. spent much of his time reading at the British Museum before embarking on a new career in a stockbroker’s office.

In December 1882 D.A. and Sybil rented a property at 76 Prince’s Square, Bayswater in west London. It was here at a tall stuccoed house that Margaret was born on 12 June 1883. She later wrote: ‘My father was disappointed: he wanted a boy’. D.A. was to remain disappointed in that Margaret was their only child. Yet he delighted in his fair-haired, blue-eyed daughter. In many respects he was enlightened and liberal. Later he and the young Margaret would discuss books and ideas together. They spent Sundays walking in the Brecon Beacons or climbing the Sugar Loaf Mountain near Abergavenny (owned by the family). D.A. paid Margaret the compliment of declaring that they were ‘not like father and daughter; we are butties’ (a term that in Wales suggests both friend and work mate and also the timber props used at the coalface).15Nevertheless, it would be Sybil who would suggest that their daughter enter the business.

Two months after Margaret’s birth the family moved to Kent. They rented Ovenden House (she misspelled it as Ovendon in her autobiography). It was the former dower-house of Lady Stanhope, on an old estate in Sundridge near Sevenoaks. Margaret spent her early years there and in the 1920s would live in the area again. Her father took up bee-keeping and commuted to the City. As a partner in a private firm he could not join the London Stock Exchange. His attempt to persuade his partners to change this by making the firm a limited company was rejected by them. But the death of O.H. Riches in 1887 altered the situation. That December the family returned to Wales. D.A. took over as manager of the sales agency of the Cambrian Collieries and they moved to Llanwern.

Llanwern House was a somewhat formal home with large rooms. It had eight bedrooms on the first floor and a further four on the second. The most striking room was the oblong saloon with a beautiful rococo-style plaster ceiling. Oak panelling in the dining room and other rooms made it seem quite dark. Margaret did not see it as a comfortable place. It seemed to reflect something of the slightly austere character of Sybil. ‘Spartan’ is the word that Margaret often used to describe her mother.

Yet she was at pains to stress that she grew up in a happy home where up to twenty guests could be accommodated easily, cared for by a resident cook and a number of domestics. The family took its responsibilities seriously and Margaret was used to entertaining from a young age. For example, in the summer of 1895 when she was twelve, members of the Loyal Cambrian Lodge of Freemasons came from Merthyr by special train ‘with their lady friends’ to Llanwern. D.A. was the Worshipful Master. After a formal reception Margaret helped to serve the picnic that preceded games of cricket, tennis and bowls.16

She was taught by European governesses (French then German) and taken to church by her mother on Sundays. One way of entertaining herself was to make up stories when she went to bed. Margaret would use her imaginative powers in this way for many a year, only breaking the habit ‘with a big effort’ in her mid-thirties.17

In contrast to the adult world of Llanwern, the six weeks of summer holidays spent at Pen Ithon were portrayed in Margaret’s autobiography as a passport to freedom and an opportunity to have company of her own age. To be an only child must have been especially disappointing in an era when large families were the norm. Although family size was declining, the average was still six living children when Margaret was small. She longed to have a large family of her own. Cousins were an important substitute for siblings and it is perhaps no coincidence that Margaret’s autobiography opens not with an account of her own home but with a glimpse of Pen Ithon in the heart of the Radnorshire countryside. Here she revelled in playing outdoors with her cousins, roaming the hills and moors on pony and by foot. Although one of Sybil’s brothers had died in his teens, the others survived and they and their children descended on Pen Ithon for their holidays.18

Here too were beloved and unconventional aunts. The senior aunt was the beautiful Janetta (Janet Boyd) widow of a deputy Lord Lieutenant of County Durham. Aunt Janetta, like George Bernard Shaw, advocated Jaeger garments. She dressed in white and dried her handkerchiefs on window-panes to save ironing. She took the young ones on walks collecting toadstools which, she maintained, were as edible as mushrooms. When they appeared on the dinner table ‘the children whooped for joy, but the other mothers sat in the deepest anxiety’.19They were gobbled up but nobody appeared to suffer.

Janetta was a talented miniaturist and exhibited annually at the Royal Academy and in Paris. She later became an ardent Theosophist. When a cousin died she sent a funeral wreath with a card saying ‘Heartiest congratulations’. Margaret’s favourite aunt, also her god-mother, was, however, Aunt Lottie20(Charlotte) Sybil’s unmarried sister who, along with many women of her day, sacrificed her desire for a profession to stay at home and look after her widowed father. Aunt Lottie enjoyed long hikes and was adored by the nieces and nephews who spent their summers at Pen Ithon. D.A. had the Thatched Cottage in Llanwern built for her. This four-roomed house was also designed by Oswald Milne and enabled Lottie to be close to her relatives in her later years. She wrote ‘No Vote, No Census’ on her 1911 census form.

Margaret had fourteen Haig first cousins. They featured much more prominently in her life than did her first cousins on her father’s side. With the exception of Peter Haig-Thomas, who was a double cousin so also part of the Pen Ithon clan, the seven children of D.A.’s sister Jemima are conspicuous by their absence from her autobiography, as is Eira, daughter of his brother Samuel.

Another change of scenery would occur at election time when the family decamped to Ysguborwen. Not content with being a businessman, much of D.A.’s career was spent in pursuing politics.21Neither father nor daughter could be accused of narrow, single-minded business interests. In the autumn of 1887 he had been asked to stand for Merthyr Boroughs as the Liberal candidate in a by-election. He was returned unopposed and remained one of its two MPs until 1910, heading the poll in contested elections in 1892 (when Wales’s most populous constituency returned him with a record 11,948 majority), in 1895 and 1900. In 1906 he received over three and a half thousand more votes than his fellow MP, the founder of the Independent Labour Party (ILP), Keir Hardie. D.A.’s family home was in the centre of his constituency.

During the 1892 election Margaret did daily lessons with her governess at Ysguborwen then, in time-honoured fashion, was used in winning electoral support. She was taught a sentence of Welsh which meant ‘Please vote for Father, everybody’ and had to utter this at the many nightly meetings. D.A. was renowned for being an uninspiring speaker. Elizabeth Phillips put it nicely in her history of pioneers of the Welsh coalfield: ‘he had not the gift of facile oratory’.22Even his biographer, Rev. Vyrnwy Morgan, generally extravagant in his praise for D.A., admitted this weakness. He explained that D.A. never brought a good speaker with him when addressing electors. Allowing Alfred Thomas MP (later Lord Pontypridd) to talk first was a deliberate foil since D.A. knew that audiences would be even more bored by the opening speaker and that in comparison he would fare better.23D.A. tended to repeat his speeches in each location and read them out. So his little daughter’s intervention perhaps helped to provide some entertainment.

D.A. now had Parliamentary business to attend. The family had a London flat at 122 Ashley Gardens, Victoria and from the age of thirteen the young Margaret Thomas – for that is how she was known at this time – attended Notting Hill and Bayswater High School, run by the Girls’ Public Day School Trust. It had opened in Norland Square in 1873 as the second of these important schools designed to give girls a good academic education. Margaret’s headmistress was Harriet Morant Jones. Starting with ten pupils, there were 400 by 1900, a number of whom won university places.

Notting Hill High had been D.A.’s idea but, perhaps due to her wish to board, Margaret persuaded her parents to let her go much further away, to St Leonards School for Girls in the medieval coastal town of St Andrews, Fife. She started there in the autumn of 1899 when she was sixteen and stayed until Easter 1902. The brainchild of the Ladies’ Educational Association, St Leonards had been founded in 1877 and was initially known as St Andrews School for Girls. Three of its first six mistresses were Girtonians. Its first two headmistresses, Louisa Lumsden and Frances Dove, were both made Dames. Experience of the strict regime at another academic boarding school, Cheltenham Ladies’ College, where both women had taught, had convinced these pioneers that ‘freedom and responsibility’ mattered as much as study.24There were no petty rules. Margaret’s headmistress was a former St Leonards pupil, Julia Grant.

Underpinning the school was a belief that girls should have as good as, if not a better, education than their brothers. It was the first school in the world to play women’s lacrosse (each house had a team), and staff encouraged a competitive spirit in sport and study, though as Margaret’s housemistress stressed, this was directed at the honour of the school and house rather than personal glory.25Margaret was not sporty, but the ethos was that girls could and should excel in whatever they undertook. It provided a challenging academic education that included Latin, modern languages and science. There was a debating society and girls enjoyed walks along the cliffs. Writing about the women of her time Janet Courtney asked ‘Did any other girl’s [sic] school in the ’nineties leave its pupils so free that they could wander at will like this?’26

Whereas Margaret’s years at Notting Hill High are dismissed in a few sentences of her autobiography, three and a half chapters are devoted to the few years she spent at St Leonards. This is described in glowing terms. The fact that the school had, by the time of writing, acquired quite a reputation for attracting girls who later became very successful, may have influenced this retrospective account. Catherine Marshall, a Liberal who became a key figure in suffragist and Labour politics, was at St Leonards with Margaret, though she was three years younger than her. The eminent Cambridge historian Ellen McArthur and the pioneer doctor Louisa Garrett Anderson, also suffrage activists, had been pupils before Margaret’s time. Mona Chalmers Watson (née Geddes) who worked with Margaret in the First World War then chaired the board ofTime and Tide, was also a former pupil, as was Helen Archdale.

Margaret’s autobiography grew out of an attempt to record her gratitude to her former housemistress Miss J.C.E. Sandys when the old lady was elderly and seriously ill. She died three years before the book appeared. One chapter is devoted to her. Presenting a striking, stylish figure who also managed to be kind and generous, Margaret suggested that she was adored by her charges and that they never felt patronised by her. At a time when many educationalists were sticklers for authority, Julia Sandys appears as a remarkable figure. She arrived at St Leonards for a temporary post and stayed for twenty-two years, first as a housemistress at Bishopshall East and then from 1896 as founding housemistress of St Rule East. Her recognition of the need for her charges to express individuality did not always endear ‘the Sandys’ to other members of staff and thus ensured unstinting loyalty from those in her house.27The House system was similar to boys’ boarding schools and each house had its own colours, traditions and loyalties. Houses also entertained the whole school with plays. Margaret acted in ‘Alice in Wonderland’ for her house, playing the part of the Duchess.

Margaret was by no means alone in stressing the value of a role model at her girls’ school. The writer and suffragette Evelyn Sharp, for example, saw her head-mistress in London as a vital inspiration.28Margaret found a lifelong friend in Edith Mary Pridden, nicknamed Prid. She was eight months younger than Margaret and the daughter of the head of a preparatory school in Surrey. The two girls began at St Leonards at the same time. They walked round the school playground in the early evenings in their hooded cloaks, earnestly discussing Renaissance and Reformation Europe, literature and politics. Prid, who was head of house in her last year, became a teacher and from 1922 to 1944 was a St Leonards housemistress at Bishopshall West. Another friend – for life – was the extravagantly named Beatrice Hestritha Gundreda Heyworth (known as Gundreda), from a military family living in Suffolk. She hailed, however, from Risca in Monmouthshire.

Recollecting her happy time in Scotland, Margaret called it ‘that very perfect present’.29She was not an outstanding pupil academically and one former pupil had a somewhat negative recollection of her as ‘very silent and rather vague’.30Her best subject was French, which she had studied at home for many years. Her appreciation of St Leonards was primarily for the way it took girls seriously, teaching and allowing them to think for themselves, though it is interesting to note that in the early 1920s at least, she was critical of the school’s failure to encourage girls to enter the professions.31The former pupil and later lawyer and educationalist, Betty Archdale, recalled that on their visits to St Leonards to see her, her mother Helen and Margaret ‘always made nuisances of themselves’ and ‘would speak out about the school, suggesting it should be pushing the girls more’.32

Nevertheless Margaret returned to St Leonards to speak at several alumnae events and to visit Prid. She was appreciative of the way that she ‘had learnt a freedom of initiative’ and ‘a freedom of mental development’. At a time when women lacked the vote and many basic rights, Margaret’s home and schooling had, in contrast to the later experiences of many girls from a similar background, been considerably more progressive than the society she now entered.

On leaving school Margaret became a debutante. Her mother had also ‘Come Out’ when she was Margaret’s age. Sybil Thomas was imbued with a strong sense of duty and appropriate behaviour so became convinced that this was the correct step for her daughter. The saloon at Llanwern was the venue for a number of balls. But, as Margaret put it, ‘One might as well have tried to put a carthorse into a drawing-room as turn me into a young lady at home’.33For three long months from May to July for three years, she endured the London season. Her afternoons involved polite tea parties. Evenings were taken over by dances interspersed by occasional At Homes. At all of these events she was chaperoned by Sybil.

Although photographs suggest a poised young lady, Margaret was by her own admission awkward, plump and excruciatingly shy. She found the whole experience painful and pointless. She would have been happy to discuss political ideas or literature but had no appetite for small talk and quickly became ‘an inarticulate lump of diffidence’.34The only time that balls were bearable was when cousins appeared: ‘Cousins were people one could talk to. Cousins were people one really liked’.35

Writing about the experience thirty years later, Margaret roundly condemned this archaic method of securing suitable marriage partners, though conceded that at the time she enjoyed the finery and had not actually rebelled against the social round that she found so uninspiring. Depicting the world of the debutante as a form of imprisonment she now denounced

The falsity and unreality of all its values, the cheapness and vulgarity of its standards and indeed of the whole atmosphere that pervades it, the stupidity of the conversation of its inmates are such it seems to me as no sane person should be asked to endure.36

She even felt that it was partly responsible for a discernible decline in western civilisation. In 1932 E.M. Delafield’s novelThank Heaven Fastingexposed the absurdity of the system’s single-minded pursuit of a husband. Drenched in irony, it was dedicated to Margaret ‘for it has sprung out of many conversations that we have held together’.37

Yet unlike most young debutantes Margaret then read History at Somerville College, Oxford. She chose to do this and was well prepared for higher education. The founder of St Leonards, Louisa Lumsden, had been a pioneer student at Emily Davies’s College for Women established in 1869 at Hitchin, the basis for what became Girton College, Cambridge. For Lumsden it had been a liberating experience. Like Margaret, she had been ‘[s]ick to the soul’ of balls and croquet and an empty life. Now she worked, read and ‘learned the worth of friendship’.38For many young women fortunate enough to attend one of the new colleges, university also meant a realisation of ambition and comradeship.

Not so for Margaret, who declared ‘Somerville was certainly not my spiritual home’.39This Was My Worldskirts over her time there. Her account says nothing about academic study or even what subjects she was studying (Responsions, the preliminary examinations in basic Latin, Ancient Greek and Mathematics). Her reports do not suggest that she had any difficulty intellectually. She was described as ‘[i]nteresting and thoughtful’ at the end of her first term in 1904. Her essays were ‘always pleasant to read and she shows considerable ability. Very promising’. The report for the next term noted that she was ‘original and independent in thought’. It also described her writing and spelling as somewhat original. She was untidy and, in contrast to her later years, ‘not perhaps a remarkably hard worker’. Nevertheless Margaret was judged once more to be ‘very promising’ with ‘real intellectual power and a vivid imagination’. Yet at Easter 1905 after only two terms at Oxford University, she abandoned her studies. The college Register simply states that she left ‘to live at home’. At this point her love affair with the man she would marry prevailed.

Had she gone straight from school to university, perhaps her reactions would have been different but, unlike those seduced by the beauty and buildings of Oxford, Margaret focused on the limitations of her college: ‘Somerville smelt frousty to me’. She suggests that she had, by the age of twenty-one, outgrown the girls’ boarding school atmosphere, particularly since neither her boarding school nor home had been stifling. Margaret had been given her own car – a rare and very privileged symbol of freedom – and was long used to discussing politics and business with her father. Female students at Oxford did not enjoy equal status with men (they sat examinations but were denied degrees) though the woman who would become so passionate about equal rights was, at this point, unconcerned about such matters. ‘Dowdy’ is the word that best summarises Margaret’s view of the dons and students she encountered.

Winifred Knox (later Lady Peck) was a History student at Lady Margaret Hall and had also been at St Leonards – ‘that windswept corner of Fife’ – with Margaret. She recalled Margaret asking her ‘if I liked going on with “this schoolgirl business”’.40The former debutante, accustomed to wealth and privilege, could not bear ‘the cloisterishness of the place’ and was irritated by

the air of forced brightness and virtue that hung about the cocoa-cum-missionary-party-hymn-singing girls, and still more the self-conscious would-be naughtiness of those who reacted from this into smoking cigarettes and feeling really wicked.41