1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

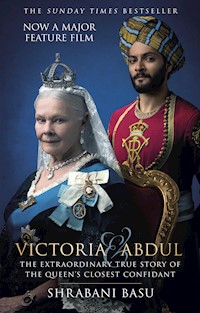

The tall, handsome Abdul Karim was just twenty-four years old when he arrived in England from Agra to wait at tables during Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee. An assistant clerk at Agra Central Jail, he suddenly found himself a personal attendant to the Empress of India herself. Within a year, he was established as a powerful figure at court, becoming the queen's teacher, or Munshi, and instructing her in Urdu and Indian affairs. Devastated by the death of John Brown, her Scottish ghillie, the queen had at last found his replacement. But her intense and controversial relationship with the Munshi led to a near-revolt in the royal household. Victoria & Abdul examines how a young Indian Muslim came to play a central role at the heart of the empire, and his influence over the queen at a time when independence movements in the sub-continent were growing in force. Yet, at its heart, it is a tender love story between an ordinary Indian and his elderly queen, a relationship that survived the best attempts to destroy it.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

For my daughters, Sanchita and Tanaya

‘I am so very fond of him. He is so good & gentle & understanding … & is a real comfort to me.’

Queen Victoria to her daughter-in-law, Louise, Duchess of Connaught 3 November 1888 Balmoral

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Working in the historic archives of Windsor Castle was one of the most pleasurable moments of writing this book. For this I have to thank Jill Kelsey, Deputy Registrar of the Royal Archives, and Pam Clark, for all their help in sorting through the material and for coming to my aid whenever I found reading Queen Victoria’s handwriting a challenge. Thanks also for the wonderful tea and cakes which provided a welcome break every day!

Thank you to Sophie Gordon, Curator of the Photographic Collection at Windsor Castle, and to Katie Holyoak of the Royal Collections at St James’s Palace for all their help and patience. I am grateful to Her Majesty the Queen for her gracious permission to reproduce material from the Royal Archives.

This book could not have been written without the complete access to the several volumes of the Reid Archives provided by Sir Alexander and Lady Michaela Reid and I am truly indebted to them for all their help and generous hospitality in their beautiful house in Jedburgh. I would also like to thank them for permission to quote from the diaries and journals of Sir James Reid and for use of photographs from his scrapbook.

My thanks to Michael Hunter, Curator at Osborne House, for all his help and especially for taking me to the basement at Osborne House to show me the menus from Queen Victoria’s time. I am also grateful for his permission to use images from the files.

I am grateful to the staff at the British Library for their patience and guidance.

In Agra, I would like to thank Syed Raju and Rajiv Saxena for their invaluable help in the search for Abdul Karim’s grave. My thanks also go to the staff at the Regional Archives in Agra for their help in tracing Karim’s files.

In Delhi, I would like to thank Krishna Menon for translating Queen Victoria’s Hindustani Journals from Urdu into both Hindi and English.

I would like to thank all the descendants of Abdul Karim in Bangalore and Karachi who allowed me to read his personal memoirs and access family photographs and memorabilia. In Bangalore, I am grateful to Begum Qamar Jehan, grand-niece of Abdul Karim and daughter of Abdul Rashid, for sharing her memories of Karim Cottage. I would also like to thank Javed Mahmood, Naved Hassan, Lubna Hassan and Samina Mahmood. In Karachi, I am grateful to Rizwana Sartaj and Sayeed-ul-Zafar Sartaj for all their help with the memoirs and their generous hospitality. I am also grateful to Khalid Masroor, Umrana Kazmi, Afza Kaiser Alam, Ishrat Hazoor Khan, Abid Sahebzadah, Hina and Sharoze, Rukshana, Nighat Afzal, Khursheed Alam, Dabeer Alam, Faisal Sartaj, Kamran Sartaj, Mahjabeen Sahebzada, Zafar Jahan, Huma Inam, Ambreen Waqar, Adil Sartaj, Asif Alam, Javaid Manzoor and Farhat Manzoor.

Very special thanks are owed to my agent, Jonathan Conway, who flagged me off on Karim’s trail, helped me structure my thoughts and whose sense of humour kept me going.

I am grateful to Simon Hamlet, commissioning editor at The History Press, for believing in the book from the start, and to my meticulous editor, Abigail Wood.

I would like to thank Aveek Sarkar, my editor-in-chief at Ananda Bazar Patrika, for his constant support and encouragement with all my books. Thanks also to Vishal Jadeja, Prince of Morvi, for his input on his ancestor. For inputs and help in various ways, I am grateful to historians Indrani Chatterjee, Sumit Guha, Shahid Amin and Kusoom Vadgama.

To my sisters, Nupur and Moushumi, I owe more than I can ever say, for all their help in Delhi and Agra, in locating Karim’s grave and sourcing translations. Thanks to my husband, Dipankar, for his patience and support and for brewing endless cups of tea, and to my daughters, Sanchita and Tanaya, for their enthusiasm in reading my early drafts, acting as my helpdesks for all technical problems and for persuading me to enter the virtual world and finally set up a website. To all of you, I owe this book.

Shrabani Basu

London

CONTENTS

Title page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

Foreword

Dramatis Personae

Queen Victoria’s Family Tree

Map of India showing Crown Territories and Princely States

Map of Britain showing Royal Palaces and Cities

Introduction

1Agra

2A Jubilee Present

3An Indian Durbar

4Curries and Highlanders

5Becoming the Munshi

6A Grant of Land

7Indian Affairs

8The Viceroy Receives a Christmas Card

9The Household Conspires

10Rebellion in the Ranks

11‘Munshimania’

12Redemption

13Death of a Queen

14Last Days in Agra

15Endgame

Epilogue

Notes and Sources

Bibliography

Copyright

AUTHOR’S NOTE

In order to retain the authenticity of the period, I have used the old British names of the various Indian cities in this book. Hence, Cawnpore for present-day Kanpur, Benares for Varanasi, Simla for Shimla, Bharatpore for Bharatpur, etc.

Queen Victoria often underlined her words for emphasis. The italicised words in her quotes indicate the words that she underlined in her letters.

The words ‘Hindustani lessons’ refer to Urdu lessons and not Hindi lessons. The word Hindustani was used by the British as a generic term for both Urdu and Hindi.

Queen Victoria learnt to read and write in Urdu from Abdul Karim.

FOREWORD

While writing the first edition of this book I was painfully aware that I had not been able to contact any of Abdul Karim’s descendants. The trail had gone cold as the family had left Agra after the partition of India and gone to Pakistan. Karim had no children and any descendants would be the children of his nephew, Abdul Rashid. With no names and no addresses in Pakistan, I had hit a dead end. I sent the book to press hoping that someone would contact me after publication.

It happened sooner than I expected. I was in Bangalore for the launch of Victoria & Abdul when I received a call from the British Council that Javed Mahmood, great-grandson of Abdul Karim, wanted to see me. It transpired that his mother, Begum Qamar Jehan, 85, was the daughter of Abdul Rashid. Frail and blind, Begum Qamar Jehan nevertheless had vivid recollections of her days in Karim Lodge in Agra, which she described as the ‘happiest’ in her life. The family showed me pictures of Abdul Karim and Abdul Rashid and told me there was a diary in Karachi. Abdul Rashid had nine children and their families lived in India and Pakistan. Begum Qamar Jehan was the last survivor of his children. Two months later I was on a plane from London to Karachi to meet the rest of the family and see the diaries of Abdul Karim. The story had come full circle.

In Karachi, I was handed the diary – a neat brown journal with gold edges – that I recognised instantly as the stationary used in Windsor. Inside was the record of Karim’s ten years in London between the Golden and the Diamond Jubilees. The pages were also filled with pictures and magazine cuttings. It was a scrapbook and journal. The diary had been smuggled out by the family along with other artefacts when they had left India in 1947 in the dark days of the partition riots.

‘There was a rumour that Karim Lodge would be attacked,’ said Zafar Sartaj, who was nine when the family left India. As Hindus and Muslims rioted in the streets of Agra, the women and children were sent in the dead of night to Bhopal in central India, where the nawab was a friend. From Bhopal they took the train to Bombay (the women hiding their jewellery in their saris) and finally an overcrowded ship to Karachi, joining the thousands of refugees leaving for Pakistan. Two trunks full of precious artefacts were sent on the goods train to Pakistan. The train was looted and the treasures never arrived. The diary, some pictures and artefacts including the tea set gifted by the Tsar of Russia and a statuette of Abdul Karim did make it, carried on the boat by the men of the family.

The English in the diary was too flawless to be Karim’s, so I suspect he dictated the words to someone. Perhaps they were written by his friend Rafiuddin Ahmed. The diaries make no mention of the unpleasantness he suffered in court, almost as if he wanted to cauterise those details. Sadly, there is nothing after 1897, so we have no account of his leaving England and the last days in Agra. In the diary he mentions that his wife was planning to publish her own journals. She would have written these in Urdu. There is no trace of this diary. The Munshi’s wife died on the boat to Karachi, an old woman who had lived in Royal palaces and seen European Royalty at close hand, but was now leaving her country as a refugee.

Karim began his journal with due modesty:

Under the shadow of Her Majesty, Queen Victoria, I a humble subject venture in the following pages to lay before the reader a brief summary from the journal of my life in the court of Queen Victoria from the Golden Jubilee of 1887 to the Diamond Jubilee of 1897. As I have been but a sojourner in a strange land and among a strange people I humbly trust all mistakes will be kindly overlooked by the reader who would extend indulgence to the writer of these pages.

He ended with the words: ‘I shall be well content if the perusal of this little work be attended with some interest or pleasure to the person into whose hands it may chance to fall.’

Over a hundred years after it was written and lost, it has been a privilege to update this edition with Karim’s diary.

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

The Royal Family

Queen Victoria – Queen of England and Empress of India

Prince Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, ‘Bertie’, later King Edward VII – son of Queen Victoria

Princess Alix, Princess of Wales, later Queen Alexandra – consort of Prince Edward

Princess Victoria, Vicky, Empress of Germany – eldest daughter of Queen Victoria

Princess Alice, Grand Duchess of Hesse – second daughter of Queen Victoria

Princess Helena of Schleswig Holstein – third daughter of Queen Victoria

Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught – son of Queen Victoria

Princess Beatrice – youngest daughter of Queen Victoria

Prince Henry of Battenberg – husband of Princess Beatrice

Prince George, later King George V – grandson of Queen Victoria

Princess May of Teck, later Queen Mary – consort of Prince George

Prince Louis of Battenberg – husband of Queen Victoria’s granddaughter

The Indians

Abdul Karim – Queen Victoria’s Munshi

Mohammed Buksh – Queen Victoria’s attendant

Dr Wuzeeruddin – Abdul Karim’s father

The Munshi’s wife

The Munshi’s mother-in-law

Hourmet Ali – Queen Victoria’s attendant and Abdul Karim’s brother-in-law

Ahmed Husain – Queen Victoria’s attendant

Sheikh Chidda – Queen Victoria’s attendant

Ghulam Mustapha – Queen Victoria’s attendant

Khuda Buksh – Queen Victoria’s attendant

Mirza Yusuf Baig – Queen Victoria’s attendant

Bhai Ram Singh – architect of Durbar Hall

Sir John Tyler – Superintendent of Agra Jail

Abdul Rashid – Abdul Karim’s nephew

Rafiuddin Ahmed – solicitor, journalist, friend of Abdul Karim

Duleep Singh – son of Maharajah Ranjit Singh deposed ruler of Punjab, Queen Victoria’s ward

Nripendra Narayan – Maharajah of Cooch Behar

Sunity Devi – Maharani of Cooch Behar

Hurwan Singh – Maharajah of Kapurthala

Sayaji Rao Gaekwad – Maharajah of Baroda

Chimnabai – Maharani of Baroda

The Household

Sir Henry Ponsonby – Private Secretary to Queen Victoria

Sir James Reid – Personal Physician to Queen Victoria

Frederick (Fritz) Ponsonby – Assistant Private Secretary to Queen Victoria

Arthur Bigge – Assistant Private Secretary to Queen Victoria, later Private Secretary to Queen Victoria

Alexander (Alick) Yorke – Groom in Waiting and Master of Ceremonies for Royal Theatricals

Marie Mallet – Maid of Honour

Lady Jane Churchill – Lady-in-Waiting

Harriet Phipps – Woman of the Bedchamber and Private Secretary to the Queen

Lady Edith Lytton – Lady-in-Waiting

Ethel Cadogan – Maid of Honour

Fleetwood Edwards – Keeper of the Privy Purse

Dighton Probyn – Private Secretary to the Prince of Wales

Edward Pelham Clinton – Master of the Household

The Viceroys

Lord Dufferin

1884–88

Lord Lansdowne

1888–94

Lord Elgin

1894–99

Lord Curzon

1899–1905

Lord Minto

1905–10

The Secretaries of State, India Office

Lord Cross

1886–92

Lord Kimberley

1892–94

Lord Fowler

1894–95

Lord Hamilton

1895–1903

Lord Morley

1905–10, 1910–14

The Prime Ministers

Marquess of Salisbury

1885–86, 1886–92, 1895–1902

William Gladstone

1880–85, 86, 1892–94

Earl of Rosebery

1894–95

Map of India showing the British India Territories and the Native States in the nineteenth century.

Map of Britain showing the Royal palaces and neighbouring cities during Queen Victoria’s reign.

INTRODUCTION

As the January mist enveloped Osborne House, a short line of mourners passed silently through the grounds towards Queen Victoria’s private apartments. In the corridor outside her rooms a tall Indian man stood alone. It was Abdul Karim, the Queen’s Indian Munshi or teacher. He had been waiting there since morning, his eyes occasionally looking out across the garden where he had spent so many hours with the Queen. In the distance, the ships in the Solent bobbed silently, their flags at half-mast.

The eighty-one-year-old Victoria had died peacefully in her sleep three days earlier, her family beside her. She was now dressed according to her wishes for this final journey to Windsor. The Royal family had been summoned to say their last farewells. The Queen lay in her coffin, her face covered by her white wedding veil. She looked, as one witness described, ‘like a lovely marble statue, no sign of illness or age’, regal in death as she had been in life. A bunch of white lilies was placed in her hand. The procession filed past – her son and heir Edward VII and his wife Queen Alexandra, the Queen’s children and grandchildren, together with a collection of her most trusted servants and Household members. Each stood for a few moments before the coffin of the woman who had ascended the throne at the age of eighteen and proceeded to define an age. The King then allowed Abdul Karim to enter the Queen’s bedroom. He would be the last person to see her body alone.

The Munshi entered, his head bowed, dressed in a dark Indian tunic and turban. His presence filled the room. The King, knowing his mother’s wishes, allowed him a few moments alone with her. The Munshi’s face was a map of emotion as he gazed at his dead Queen, her face lit by the softly glowing candles. She had given him – a humble servant – more than a decade of unquestioned love and respect. His thoughts raced through the years spent in her company: their first meeting when he had stooped to kiss her feet at Windsor in the summer of 1887; the lazy days spent together as he taught her his language and described his country; the gossip and companionship they shared; her generosity to him; her loneliness that he understood. Above all, her stubborn defence of him at all times. He touched his hand to his heart and stood silently, fighting back tears. His lips mouthed a silent prayer to Allah to rest her soul. After a final look and bow he left the room slowly as two workmen closed and sealed the Queen’s coffin behind him.

At her funeral procession in Windsor, Abdul Karim walked with the principal mourners. The elderly Queen had given this instruction herself, despite what she knew would be intense opposition from her family and Household. She had ensured her beloved Munshi would be written into the history books.

But only days after the Queen’s death, the Munshi was woken by the sound of loud banging on his door. Princess Beatrice, Queen Alexandra and some guards stood outside. The King had ordered a raid on his house, demanding he hand over all the letters Victoria had written to him. The Munshi, his wife and his nephew watched in horror as the letters in the late Queen’s distinctive handwriting were torn from his desk and cast into a bonfire outside Frogmore Cottage.

As the ‘Dear Abdul’ letters burnt in the cold February air, the Munshi stood in silence. Without his Queen he was defenceless and alone. Postcards and letters from the Queen, dated from Windsor Castle, Balmoral, the Royal yacht Victoria and Albert and hotels across Europe, crackled in the flames. The Queen used to write to the Munshi every day, signing her letters variously as ‘your dearest friend’, ‘your true friend’, even ‘your dearest mother’. The Munshi’s distraught wife sobbed beside him, tears streaming down her veiled face. The nephew looked frightened as he was ordered to bring out every scrap of paper from the Munshi’s desk with the Queen’s seal on it and confine it to the mercy of the guards. The Munshi’s family, once so essential to the Royal Court, stood bewildered, treated like common criminals. With Queen Victoria in her grave, the Establishment had come down hard and fast on the Munshi. King Edward VII asked him unceremoniously to pack his bags and return to India.

The fairytale – that had begun the day the young Abdul Karim had entered the Court in 1887 – was over.

Karim had been a gift from India to celebrate the Queen’s Golden Jubilee. Strikingly dressed in a scarlet tunic and white turban, the handsome twenty-four-year-old youth had arrived from Agra, the home of the Taj Mahal – the world’s most beautiful monument to love. Initially a servant waiting at the Queen’s table, his rise through the ranks was swift. Within months he was cooking the Queen curries and, soon after, became her teacher or ‘Munshi’. Whilst his colleague from India, Mohammed Buksh, remained a waiter, Karim eventually became the Queen’s highly decorated Indian secretary. He was also the lonely monarch’s closest confidant, filling the shoes of John Brown, her trusted Scottish gillie, who had died four years earlier.

If the Royal Household had hated Brown, they abhorred Karim, deeply suspicious of his influence over the Queen. These fears were strengthened by the increasingly violent calls for Indian independence that were filtering through to Court. But the Queen cared little for what others thought. She defended her ‘Dear Munshi’ relentlessly, handing him cottages in Windsor, Balmoral and Osborne and extensive lands in India. She insisted that he be treated on a par with the rest of her Household and had his portrait painted by the artists Swoboda and Angeli. She even allowed him to carry a sword and wear his medals at Court. She fussed endlessly about Karim’s welfare, gave him permission to bring his wife and family to England and praised him to her family and ministers. Throughout the last ten years of her life, Victoria stood like a rock by his side.

And the more the Household complained about Karim, the more fiercely the Queen defended him, seeming to delight in her verbal spats with them over the Munshi. She went out of her way to protect Karim from any of her Household’s racism. At a time when the Empire was at its height, a young Muslim now occupied a central position of influence over its sovereign. On a visit to Italy, Karim was mistaken for a young Prince with whom the Queen was in love, so majestic did he look as he rode in his private carriage through Florence.

What was it about the Munshi that attracted the Queen? Was he a soulmate for this lonely, heartbroken, elderly woman, someone who understood her and to whom she could relate? Given the current climate towards Muslims in the West, that a Muslim should have played such a key role in Queen Victoria’s Court is all the more intriguing and relevant. Did the Queen represent a more enlightened and tolerant attitude, even at the peak of her Empire? Were the dawn raids on Abdul Karim’s house after her death a precursor of things to come?

These and a hundred other questions entered my mind as I took the ferry across the Solent to the Isle of Wight, where I had first discovered the mysterious Abdul Karim.

He had looked out at me from his portrait painted by Rudolph Swoboda that hangs in the Indian corridor at Osborne House. I had gone to Osborne in the centenary of Queen Victoria’s death in 2001 to see the restored Durbar Room whilst researching Queen Victoria’s love for curry for an earlier book. What unfolded before me was her affection for the man who had introduced her to curry.

Abdul Karim was painted in cream, red and gold by the Austrian artist. The portrait showed a handsome young man in a reflective mood, holding a book in his hand. He looked more like a nawab than a servant. The artist seemed to have captured the Queen’s romantic vision of the subject. I learned later that Queen Victoria had loved the painting so much she had copied it herself.

Along the Indian corridor of Osborne House were portraits of Indian craftsmen, specially commissioned by the Queen. Weavers, blacksmiths and musicians stared back from the walls, all meticulously painted so the Queen could glimpse the ordinary people of India. The striking life-size portrait of Maharajah Duleep Singh painted by Winterhalter stood out amongst the canvases. It captured the Queen’s fascination for the young boy who had presented her with the Koh-i-Noor – one of the world’s largest diamonds and still a part of the Crown Jewels – when the British had defeated the Sikhs and annexed the Punjab after the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849.

The Durbar Room, restored by English Heritage to mark the centenary of the Queen’s death, had its own revelations. The room spoke to me of the Queen’s love for India, the country she knew she could never visit, but which fascinated and intrigued her. If the Queen could not travel to India, then she would bring India to Osborne. The marble ceilings, the intricate carvings, the balconies with their Indian-style jali work were the Queen’s Indian haven. Here she sat as Empress of that faraway land to sense its atmosphere. Fittingly, it was at her beloved Osborne, with its collection of Indian antiquities, that she had died. Was her love for Abdul an extension of her love for India and the Empire, her way of touching the Jewel in the Crown?

Five years after my visit to Osborne House, I found myself tracing Abdul Karim’s past in his home town of Agra, city of the Taj. My good-natured young Sikh driver, Babloo, looked like a taller version of England cricketer Monty Panesar, although he fancied himself more as Formula 1 racer Michael Schumacher than the gentle leftarm spinner from Northamptonshire. He had driven me down from Delhi in three hours, speeding along the three-lane expressways that have been built over the last few years as proud symbols of India’s march to globalisation. Soon we were bumping along the narrow roads of Agra, past internet cafes, Kodak instant photo shops and electrical outlets stacked high with frost-free refrigerators and washing machines; material evidence of India’s burgeoning middle class and hunger for consumerism.

I was meeting a local journalist, Syed Raju, a wiry man in white Nike trainers, who spoke endlessly on his mobile phone and clutched two small notebooks. Political dignitaries and Bollywood film stars visiting the Taj provided his more glamorous assignments, but he had never heard of Abdul Karim and knew nothing of a place called Karim Lodge. After two days, there was still nothing. The family may have left for Pakistan, he said. Perhaps Abdul Karim died there. I could find nobody in Agra that knew anything about him.

I told him that Karim had died in Agra in 1909 and would have been buried in the city. Given his position, he would surely have had a prominent gravestone, I suggested, mentally preparing to comb the burial grounds of Agra searching for his grave and to knock at every mosque to ask for information. By evening we were in luck. Raju had found a lead. He knew another journalist who had recognised the name. He wrote historical articles in a local Agra newspaper. That night we drove to the offices of the Dainik Jagaran, one of the highest circulated Hindi newspapers in India, recently acquired by the Irish millionaire, Tony O’Reilly, proprietor of The Independent.

Skirting the bales of newsprint lying near the entrance, we went up some narrow winding stairs to the editorial offices where computers whirred in the small, dimly lit newsroom. A man with a peppered grey beard met us. He was Rajiv Saxena, the newspaper’s chief sub-editor. His bearded face broke into a welcoming smile.

‘You are looking for Queen Victoria’s ustad!’ he said. ‘Yes, I know where he is buried. Tomorrow we will go there.’

Panchkuin Kabaristan in Agra was once a burial ground for the Mughals. Now it is a dusty expanse of mud and grass, with buffaloes grazing amongst the crumbling gravestones. A few mausoleums stand intact – graves of the lesser relatives of the Mughal emperors – their semi-precious carvings vandalised and innocuous graffiti on the walls. No one comes here anymore, said Nizam Khan, the elderly Muslim caretaker of the graveyard. He cut a lost figure in the wilderness, looking after the graves that time and history had left behind. Khan led the way purposefully through the field, picking his way past unmarked graves, bramble bushes and stray dogs basking lazily in the winter sun. The dogs soon joined our procession, wagging their tails and running ahead, as if providing an escort to the Munshi’s lonely grave.

At last, Nizam Khan stopped and pointed. ‘This is it,’ he announced dramatically, sensing our anticipation. Resting on a high plinth and surrounded by smaller graves, was a red sandstone mausoleum. We mounted the steep stairs to the tomb. Inside were three graves. Abdul Karim’s lay in the middle, his father’s grave to his right. The marble gravestone, once studded with semi-precious stones, had been plundered long ago. There was no one left to tend the grave now or bring flowers. The remainder of Karim’s extended family had left for Pakistan after the Partition in 1947. The man who had lived in Windsor Castle and been the Empress’s closest confidant now lay in a bleak unkempt graveyard guarded by an elderly caretaker and a few stray dogs. His Queen had provided generously for him and ironically it was the crumbling of her Empire that had changed the world of his descendants. The land had gone, given to Hindu families who had come as refugees from Pakistan, and the high mausoleum – once fairly grand – now overlooked only derelict graves.

Nizam Khan read out the words on Abdul Karim’s gravestone in Urdu, his voice rising and falling as he orated, carrying across the desolate fields:

This is the last resting place of

Hafiz Mohammed Abdul Karim, CIEVO,

He is now alone in the world

His caste was the highest in Hindustan

None can compare with him

The poet finds it difficult to praise him

There is so much to say

Even Empress Victoria was so pleased with him

She made him her Hindustani ustad

He lived in England for many years

And let the river of his kindness

flow through this land

The poet prays for him

That he finds eternal peace in this resting place

Inscribed in Urdu behind the gravestone were the words: ‘One day everybody has to enjoy the sweetness of death.’

On my return to the Royal Archives at Windsor, I sat in the castle’s Round Tower looking through the thick volumes of Queen Victoria’s Hindustani Journals. For thirteen years the elderly Queen had written a page every day. Abdul Karim would write a line in Urdu, then in English and a third line in Urdu in roman letters so the Queen could hear the rich cadences of the words. The Queen diligently copied the lines, covering the page in her sprawling handwriting. Through winter evenings and balmy summer days, the Journals became the strongest bond between Victoria and Abdul. The pages entered in it were their own private space, away from the problems of Court, a troublesome family and the ever suspicious and demanding Household. The Queen never missed a lesson. She would complain almost coquettishly if Karim was absent, writing how much she missed her ‘dear Abdul’ when he went on leave. We can hear Abdul’s voice in his written thoughts at the end of each volume as he assessed the Queen’s progress.

As I sat daydreaming, looking out of the window at the crowds of tourists below, a pink piece of blotting paper floated out of the Journals. It had been lying untouched in the Journal for over a century. I held the strip of paper in my hand and pictured Karim, dressed in all his finery, standing by the Queen, gently bowing down to blot her signature. It was as if an entire chapter of history – that the political establishment had tried to destroy – was lying in front of me: the story of an unknown Indian servant and his Queen, of an Empire and the Jewel in the Crown, and above all, of love and human relationships.

1

AGRA

The call of the muezzin to prayer floated over the city of Agra in the dawn, waking up the residents. The summer heat had made even the nights unbearable and Abdul Karim was almost relieved to leave his bed. His young bride was still asleep. It was the few tranquil minutes of the morning that he loved. He walked on the terrace surveying the roof-tops of the neighbouring houses. Not far away he could see the high walls of the Central Jail where he and his father worked. Soon all of Agra would be awake and buzzing, the gullies and bazaars full of traders, artisans, tongah wallahs and people getting about their work. Cows would stand on the crowded streets lazily chewing the vegetables from the vendors’ carts and elephants would sway through the narrow lanes carrying their loads of logs, grain, cotton and carpets to the mandis and factories.

As Karim sat down on a mat to pray, the first rays of the sun fell on the Taj Mahal, bathing it in a warm glow as the gentle waters of the Yamuna flowed behind. Further upstream, strategically positioned at a bend in the river, stood the impressive Agra Fort, a towering piece of architecture built in red sandstone by the Mughal Emperor Akbar in the sixteenth century, when he was at the pinnacle of his glory. Agra was known then as Akbarabad, capital city of the Mughal Empire. Within the walls of the Fort lay the history of four generations of the Mughal Emperors: tales of war, romance, court intrigues and brutality. It was in the splendour of the Diwan I Khas, or the Hall of Private Audience, with its marble columns inlaid with rich gemstones – lapis lazuli, garnet, jade, jasper and carnelian – that Emperor Shah Jehan had received the embassies of William Hawkins and Sir Thomas Roe, who came seeking permission for the East India Company to trade with India. The English and Dutch subsequently established their factories in Agra. It was in the Jasmine Tower of the Fort that the ageing Shah Jehan was imprisoned by his son Aurangzeb, and here that he languished till his dying day gazing through the tiny prison window at his beloved Taj Mahal, the mausoleum he had built for his Queen, Mumtaz Mahal.

Karim’s family had lived in Agra for the last four years, enjoying the city’s rich Mughal heritage, which was now combined with the spit and polish of British administration. The original family home was in nearby Farrukhabad in the United Provinces. Karim’s father, Haji Wuzeeruddin, had been brought up by his stepfather, Maulvi Mohammed Najibuddin, who took care to provide him with a good education. In 1845 Najibuddin was employed as private secretary to an Englishman, William Jay, who was very kind to the family, encouraging young Wuzeeruddin and employing him in his services. From 1856 to 1859, Haji Wuzeeruddin worked in the Vaccine Department of Agra. In 1861 he received his diploma as hospital assistant and served in the 36th Regiment North India from November 1861 to March 1874 working in various cantonment towns in north and central India. It was in Lalatpur cantonment near Jhansi that Abdul Karim was born in 1863.

Karim was to grow up in an India very different from that of his father – one that was governed directly by the British Crown and not the East India Company. Six years earlier, the land of his birth had been the principal theatre-ground of the Indian Mutiny of 1857. Haji Wuzeeruddin had been an eye-witness to the event that would be described later by Indian nationalists as the First War of Indian Independence. Karim’s birthplace, near Jhansi, was synonymous with the fiery Lakshmibai, the Rani of Jhansi, who had donned battle armour, mounted her faithful steed and led her troops against the forces of the East India Company during the Mutiny.

Soldiers from the cantonment of Meerut in the United Provinces had taken up arms against their commanders, liberating imprisoned soldiers and killing many English officers. Soon neighbouring towns of Agra, Cawnpore (modernday Kanpur) and Gwalior were captured by the mutineers and the rebels began plotting the downfall of the East India Company. They looked north to Delhi, where the ageing Mughal Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, still held Court in the Red Fort and chose him as their symbolic leader. The eighty-two-year-old, famous more for his ghazals and Urdu poetry than for his statesmanship, declared himself Emperor of India, directly challenging British authority. The rulers from various central and northern Indian states rallied under his name. The mutineers met with initial success, British forces not being prepared for the rebellion. The siege of Delhi lasted for nearly four months, but on 21 September, Delhi fell to the Company troops. Bahadur Shah Zafar was given a brief trial and exiled to Rangoon in Burma; the last Mughal Emperor and descendant of Tamerlane, leaving Delhi unceremoniously in an ox-cart, ending an era of Indian history.

The British revenge was extreme. Hundreds were hanged after elementary trials and others were executed by tying them to the mouths of cannons and blowing them up. Delhi was desecrated, many of its historic monuments raided and plundered, artefacts and manuscripts looted and destroyed, and hundreds of ordinary civilians executed. The residents of Agra were fined collectively for helping the rebels. Many Mughal buildings and houses in Agra were demolished. The blood of the mutineers stained the dusty plains of central and northern India as they were hanged from trees and public posts as a warning to anyone who challenged Company rule in the future. Karim was born on the same land six years after the guns of the mutineers were silenced.

He was only thirteen when Queen Victoria was given the title of Empress of India in 1876 by Benjamin Disraeli. The East India Company had been dissolved in 1858 and ruling power transferred directly to the British Crown. The Secretary of State for India now dealt with Indian affairs in Westminster and the Viceroy represented the Crown in India.

The Queen was delighted with her new title and sent a message to the Delhi Durbar held on 1 January 1877: ‘We must trust that the present occasion may tend to unite in bonds of yet closer affection ourselves and our subjects, that from the highest to the humblest all may feel that under our rule the great principles of liberty, equity and justice are secured to them.’ Karim would have heard this message as a teenager living in Meerut City.

With the British Crown now directly in charge of the administration of the provinces, radical changes were made. The railways were constructed with frenetic zeal to provide direct and quick access to the interior of the country, linking Cawnpore, Lucknow, Meerut and Agra, the major northern Indian cities that had been touched by the Mutiny. The East India Railway connected Calcutta directly to Delhi, and the Central India Railway connected cities like Bombay and Baroda to the north.

After the Mutiny, the British had regulated the running of the Indian army and Karim lived his early life in the cantonment of Lalatpur and Meerut City, watching the parading soldiers and dreaming of one day being in uniform. He was the second of six children, with an elder brother, Abdul Azeez, and four younger sisters.

The 36th Regiment then moved to Agra and Karim was placed under a regular tutor, though he spent most of his time with the other boys playing in the fields. ‘In my elementary education I regret I spent more time in play than in work,’ he wrote later in his memoirs. ‘Being my mother’s favorite, I was rather over-indulged and my studies were very irregular.’1 In 1874 Haji Wuzeeruddin was transferred to the Second Regiment of the Central India Horse which was stationed in Agar, an area on the border of Rajputana and the Central Provinces (present-day Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh). After a year’s stay in Agar, Wuzeeruddin sent for his family who travelled there by bullock carts covering twenty-two miles a day. It took them one month to reach Agar.

In Agar, Karim’s parents paid more attention to his education and he was handed over to a private tutor, a Maulvi (Muslim scholar), with whom he studied till the age of eighteen. He was taught Persian and Urdu, the Court language of the Mughals, and read books on Islam and the Prophet.

In 1878 Britain was entangled in the Anglo-Afghan war and the following year, Haji Wuzeeruddin received orders to go to Afghanistan with the First and Second Regiments of the Central India Horse under the command of Col Martin. Karim, who was seventeen at the time, was overcome with grief at this news as he felt he would never see his father again.‘I at once made up my mind not to remain behind in ease and comfort and let my father go unattended to encounter the hardships of the campaign, especially when I felt confident I could be of assistance to him,’ he wrote. Despite the objection of his parents, Karim accompanied his father on the journey.

They passed through Lahore, ‘a splendid city’, where the mausoleums and shrines were ‘magnificent and numberless’, to Jhelum, Rawalpindi and Peshawar, stopping at the forts of Basawal, Sandamuck and Jellalabad. Karim was eager to explore, taking in the rugged countryside and the tribal terrain. It was famously to the fort of Jellalabad that the exhausted British soldier, Dr William Bryden, had come on 13 January 1842; the lone survivor of 16,000 troops who perished on the road from Kabul during the First Afghan War of 1837–42, a picture etched forever in the minds of the British administration and captured dramatically on canvas by artists to remember the war’s high casualties. Nearly forty years later, Afghanistan remained on the boil and the British constantly feared that the Russians would attempt to enter India through Afghanistan. The Second Afghan War broke out in 1878, after the British and the Russians clashed over setting up a mission in Afghanistan.

No sooner had Wuzeeruddin’s regiment reached Jellalabad, when they were ordered to start at once on the famous march to Kandahar under General Roberts in August 1880. Roberts had been a junior officer during the siege of Delhi in the Mutiny. Within three hours the soldiers were on the road. Wuzeeruddin accompanied them as a medical assistant, but despite Karim’s pleas to remain, he had to turn back as he had no formal position in the army. Karim covered the 500 miles back from Jhelum to Agra alone, returning to find his mother sick with worry.

The historic march from Kabul to Kandahar with 10,000 men ended in a resounding British victory and the defeat of the Afghan lord, Sardar Mohammed Ayub Khan. A few months later the Second Afghan War was over and General Roberts returned triumphantly to England where he was knighted.

When Wuzeeruddin returned after the war, he was given four months’ leave. ‘All our family were so pleased and happy to see his face once more,’ wrote Karim.‘We were all thankful to Providence for having brought us all together again.’

Karim travelled with him again to Kabul, where he marvelled at the sight of the Khyber Pass, the fifty-three-kilometre narrow road that cuts through the Hindu Kush mountains, used by invaders for centuries since the time of Alexander the Great. The precipitous cliffs guarded by the fierce Pashtun tribes, the austere forts standing in bleak mountain deserts and the famous bazaars of Kabul overflowing with watermelon and dry fruits, were a far cry from the gentle plains of the Yamuna that Karim had grown up in.

When they returned, Karim took up employment with the Nawab of Jawara, who appointed him as the Naib Wakil (assistant representative) to the Agency of Agar. Meanwhile, the British government issued an order permitting the exchange of military for civil appointments and Wuzeeruddin transferred to the Central Jail at Agra. It was while Karim was working for the nawab that his family arranged his marriage in Agra and Karim took two months’ leave to travel for his wedding. He returned to Agar feeling lonesome and homesick. ‘There was however no help for it as duty must conquer sentiment so I remained,’ he wrote, working steadily for another twelve months before he took a month’s leave to return to his family.

After three years’ service with the Nawab of Jawara, Karim resigned and joined his father at Agra, taking up a position as a vernacular clerk to the superintendent of the Central Jail. His salary was fixed at Rs 10 a month. Both father and son were now employed at the same place. Wuzeeruddin moved with his family to the Hariparbat area near the jail. The family owned about five acres of land in the surrounding area. Karim enjoyed hunting with his brother in the forests around Agra, which were full of deer, black buck and tigers. The surrounding lakes of Rajasthan were the nesting grounds of a variety of wild fowl, particularly the migrating cranes who came every winter from Siberia and stayed till spring. Agra, the city of the Taj, was now the stable family home. It was here that Karim settled down with his young bride. His wife’s brothers also worked at the jail and the closely-knit family soon became well known in the area.

On that summer morning in Agra, when Karim looked out over the city, he did not know that his life was about to change.

The first stirrings of human life had begun and the banks of the Yamuna were already crowded with camels and elephants, led by their owners to drink and carry back the day’s water supply. In the markets of Loha Mandi and Sadar Bazar the traders were opening their red cloth-bound ledgers and fixing the commodity prices for the day. Spices, cotton, wheat, gram, oil, sugarcane – all the produce of the fertile region – would pass through their keen fingers as they struck their deals. Agra had been the hub of trade activity since Mughal times and so it continued under the British as the trade corridor that connected Central and West India on one side and the rugged North-West on the other.

Artisans were also at work. Carpet weavers were streaming into the looms of Otto Weyladt and Co., the largest carpet manufacturers in Agra, to weave the finest carpets for the export market. In the narrow streets and shops around the jail, the craftsmen were beginning their delicate job of stone inlay work, practised for centuries since the time of Emperor Akbar, cutting the huge slabs of marble and fashioning them into exquisite handicrafts set with precious gems.

As the clinking sound of their hammer and chisel striking the stone began to fill the air, Karim said goodbye to his father, adjusted his pugree and strode out of the house towards the Central Jail. A tall man, nearly six feet in height, with dark intense eyes and a neatly clipped black beard, he looked impressive. Today was an important day. He had been summoned to meet with John Tyler, the jail’s superintendent.

Tyler was a busy man. A doctor by profession, he was well loved for his warmth and geniality but known for a lack of tact and a hot temper.2 As an Anglo-Indian he was fluent in Hindustani and at ease with the natives. Tyler had just returned to Agra from London from the successful Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886, at the inauguration of which the second verse of the English national anthem had been uniquely sung in Sanskrit. He had been in charge of thirty-four inmates from Agra Jail who had attended the exhibition. The inmates had been schooled in carpet weaving as part of the jail rehabilitation programme, a tradition started by Emperor Akbar who brought the finest carpet weavers from Persia to India as teachers. Since the prisoners had all the time in the world, they could work at leisure to produce the exquisite Mughal carpets in silk, cotton and wool. The jail carpets were internationally famous and the tradition of training the inmates was carried on by the British administration.